Wire Wheels Magazine Issue4

Wirewheels magazine is about anything that looks good on wire wheels, including vintage and post vintage cars made by Bentley and Rolls-Royce in Derby and Crewe, Jaguar, Triumph and MG, and including the Spitfire, the TR6, the GT6, the Vitesse from Triumph, and pre-war and postwar MGs including the TA, TC, TF, MGA, MGB, MGB GT. It also features stories about Ayrspeed, Cobra, Jensen, Reliant, Marcos, Bristol, AC, Austin, Healey, Morgan, Aston Martin, Daimler V8, Lagonda, Lotus, Gordon Keeble, Delage, Delahaye, Packard, Rover, Sunbeam Tigers, Talbots, TVR. It has technical stories concerning instruments, design, boat-tails, speedsters, metal fabrication, restoration, welding, engines, pistons, bores, rebores, conrods, bearings, cams, ignition coils, starters, distributors, condensers, coils, HT leads and wires, chokes, Webers, superchargers, turbos, wheels, gearboxes, distributors, carburettors, fuel, petrol, oil, tools, service, clutches, radiators, cooling, heating, overheating, brakes, friction, discs, drums, shock absorbers, dampers, telescopic and friction, handling, suspension, anti roll bars, rollbars, seat belts, harnesses, steering wheels, headlights, lights, spotlights, bulbs, reflectors, MIG and TIG welding, English wheels, slip rollers, aluminium, steel, louvres, louvers, scoops, motorcycles, Bonnevilles, bikes, cyclecars and trikes, helmets and jackets. It features reviews, road trips, rally, history, photography, artwork, racing, car building and rebuilding, specials, books, travel, whisky, watches, cigars, jokes, stories, satire, flying, aviation and the politics of climate change.

Wirewheels magazine is about anything that looks good on wire wheels, including vintage and post vintage cars made by Bentley and Rolls-Royce in Derby and Crewe, Jaguar, Triumph and MG, and including the Spitfire, the TR6, the GT6, the Vitesse from Triumph, and pre-war and postwar MGs including the TA, TC, TF, MGA, MGB, MGB GT. It also features stories about Ayrspeed, Cobra, Jensen, Reliant, Marcos, Bristol, AC, Austin, Healey, Morgan, Aston Martin, Daimler V8, Lagonda, Lotus, Gordon Keeble, Delage, Delahaye, Packard, Rover, Sunbeam Tigers, Talbots, TVR.

It has technical stories concerning instruments, design, boat-tails, speedsters, metal fabrication, restoration, welding, engines, pistons, bores, rebores, conrods, bearings, cams, ignition coils, starters, distributors, condensers, coils, HT leads and wires, chokes, Webers, superchargers, turbos, wheels, gearboxes, distributors, carburettors, fuel, petrol, oil, tools, service, clutches, radiators, cooling, heating, overheating, brakes, friction, discs, drums, shock absorbers, dampers, telescopic and friction, handling, suspension, anti roll bars, rollbars, seat belts, harnesses, steering wheels, headlights, lights, spotlights, bulbs, reflectors, MIG and TIG welding, English wheels, slip rollers, aluminium, steel, louvres, louvers, scoops, motorcycles, Bonnevilles, bikes, cyclecars and trikes, helmets and jackets.

It features reviews, road trips, rally, history, photography, artwork, racing, car building and rebuilding, specials, books, travel, whisky, watches, cigars, jokes, stories, satire, flying, aviation and the politics of climate change.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

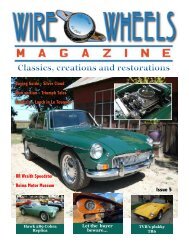

Classics, creations and restorations

Lagonda Burps

Roadtrip Belgium

Trip prep advice

Orphaned Alvis body

MGB propshaft overhaul

Issue 4

Boat-tailed Wraith

Part 4

To Hungary in a

Speedster? No.

RR club

Vancouver chapter

Contents

Hawk 289: upmarket Cobra replica

When replica makers are obsessed with their subject,

they tend to make good cars. Here’s one.

Roadtrip: Belgium in a Speedster

That was the plan, anyway. Turned out it was an inadequately

planned plan.

Lagonda Burps: economics of upscale classics

It is 100% cheaper to run a serious classic car as a

daily driver than a serious modern car.

Hands On: Mini Marcos Part 3

Plumbing, subframe trial fitting and an ancient grudge.

Alabama in Almhult: a Yank car show in Sweden

The Swedes are obsessed with classic American cars.

Fair enough, some of them are good.

Not good vibrations: MGB propshaft overhaul

Propshaft universal joints are universally fixed the

same way. Here’s how.

WireWheels Magazine is published by

Ayrspeed Automotive Adventures Ltd -

which is the venue for the orchestration of one-off cars such as

the boat-tailed Rolls special, and for prototyping other ideas, if

sufficiently interesting.

www.wirewheelsmagazine.com

iain@wirewheelsmagazine.com

Syncronicity: orphaned Alvis body rehomed

1937 Charlesworth body from a Vancouver special

build ended up on another 1937 Alvis in Australia.

Ayrspeed Diaries: boat-tailed Wraith Part 4

The rolling chassis gets its engine and box, the pedals

and steering are designed, and the exhaust built.

Trip Prep advice: checklists

The Great 2020 Lurgy has parked many classics for a

year. Check them carefully before disinterment.

Plus: L’Ayre du Temps; One will be at one’s Club

Editor: Iain Ayre

Designer: Jelena Ayre

No liability is accepted for any information published herein: the

editor’s degree is in English and Art. His automotive opinions and

for that matter his chassis concepts are based on writing 1000

motoring articles and 20 books, but he has no formal engineering

qualifications. Caveat emptor, innit.

www.ayrspeed.com

iain@ayrspeed.com

Gentlemen, start your engines

It does occur to me that the Gentlemen title is heading

slightly in the direction of a tendency to drift towards

the masculine gender arena rather than being fashionably

woke: but the phrase is a reference to 1950s

racing, when there were virtually no ladies racing at

all. There are still only a few, and the number may

never rise much.

Through many years of automotive writing, I’ve

always encouraged women to get involved in petrolhead

games, and one or two of my female friends are

enthusiasts: but cars as toys are simply not something

that appeals to many women, in much the same way

that knitting doesn’t appeal to many men. That’s just

the way it is.

It’s peculiar that riding ponies has a huge appeal to

many young women, but riding motorcycles doesn’t.

I’ve done both, and the buzz is very similar: speed,

danger, power, limited control, intensity of being alive.

Chat about fetlocks and manes with such young ladies

is lively, but their eyes glaze over when the parallel

thrill of bikes is mentioned. Maybe it’s because horses

share being dim and disobedient with many men, but

they mostly have rather nicer natures.

As long as everybody of whatever sex or gender gets

to do what they want, none of this matters. Some men

try to keep women out of car games: not really sure

why that would happen unless they just don’t like

women. Which makes no sense. Some people are a

pain in the bum, but gender doesn’t really come into

that. Men who don’t like women have a problem with

themselves, really. Would I try to join a knitting club if

I liked knitting, even if it were 100% female? I hope I

would have the courage to do that. It would probably

work out okay, although it would be odd at first. The

knitting would be the thing, and after a while I’d probably

be just one of the girls. Come to think of it, at

school I headed for arts and languages with the ladies,

while the more laddish lads did maths, physics and

chemistry which certainly made my eyes glaze over.

Way back in my youth, there was a girl from a different

corner of my local pub who was slightly scary,

because she had rebuilt a Chevrolet Camaro herself.

This was suburban London, with student budgets, and

my Vitesse had a pretty big engine at two litres. Her

engine was five and a half litres! Not only that, but

This is the Camaro in question. I always thought

its hips were a sublime piece of automotive design,

so I photographed just that section of the car.

she had restored it herself, including cutting off the

rear quarter and welding on a new panel. It was also

painted black, which requires perfect bodywork. The

deepest I’d been into my car was taking the head off

and grinding the valves in to get it to run on six cylinders,

and some minor P38 action and touch-ups. She

was also clever and rather beautiful, with very long

blondish hair, and when she fired up the Camaro and

blatted off down the high street, it was very impressive,

but it never even crossed my mind to ask her

out. She was doing petrolhead stuff ten times as well

as I could do it, so I just admired her from a distance.

In retrospect, everybody else would have been doing

the same, so she probably spent Saturday nights alone

watching telly.

A good few years later, I was supply teaching. I’d

taken an English and art teaching degree, because I

didn’t think I’d end up staying in the UK, and a British

teaching degree in English gets you a job the same

day in pretty well any major city in the world. Supply

teaching is horrible, and sometimes involves covering

for somebody ill with stress problems because their

class is unusually nasty. With experience, you learn to

do it to them before they do it to you: every first lesson

with a new class involves the boring and unpleasant

business of establishing who’s boss, and not doing

that is not an option. I stopped doing high school work

and only did middle school in the end, because it was

just too much of a pain. I’ll happily muster up all the

patience it takes to teach anybody who wants to learn,

but if it’s just a contest of wills over control, forget it.

In a weird synchronicity, I found myself covering

for Ms Camaro. She was having trouble with a first

year middle school class, which makes them 8 or 9

years old. Sometimes particular classes are just bad

news, with an unusually high percentage of violent or

disruptive children. What sort of psychopathic little

monsters would be too much for a woman who had

built her own Camaro and out-machoed every male I

knew? The prospect of dealing with such a class was

a bit daunting, but FFS, they’re only babies, how bad

can it be? As it turned out, they were unruly, but not a

bad bunch at all, just lively. It does take a great mental

effort to control any class at all, and the incidence of

teachers coming down with stress illnesses and mental

problems is very high. It’s the toughest job I ever had,

and that includes driving Trekamerica tours coast to

coast with two hours’ sleep a night.

Ms Camaro got out of the state sector and got a job in

a private school in Knightsbridge, which went much

better – parents who pay for education tend to back

teachers up rather than suing them - and we met for

lunch occasionally. The first time was in the cavernous

Pizza on the Park at Hyde Park Corner in central

London. I was in a back corner, and I heard her arrive

on the bike which she rode to commute into town. (Of

course she did. It was a Triumph Bonneville). Six feet

tall, she strolled across the big restaurant, swinging a

helmet and clad in skin-tight black leather. By the time

she got to my table, the whole place was pretty well

silent, and every eye was following her to see which

celebrity she was going to have lunch with. Couple of

hundred people looking at me thinking who the hell is

that, he’s not famous at all, doesn’t even look rich. A

moment to treasure.

L’Ayre du Temps

The story of Charles J Thompson and the Cortina tail

lights came to mind the other day. I interviewed the

Cortina’s designer when editing Classic Ford magazine.

Talking to car designers always went well when I

mentioned my own attempts at car design: they would

open up and treat me as a fellow creative rather than

as a reporter. A couple of times, a booked half-hour

interview stretched into lunch and most of a day.

Thus it was with Charles Thompson, a thoroughly nice

man, at least until properly riled.

All the best creatives have been fired or have walked

out of lucrative jobs, and Charles’s 37 years of employment

with the Ford Motor Company nearly came

to an abrupt end over Cortina tail lights.

Charles was born in Poona, India, and was educated in

Lucknow, but ended up in the UK where he did National

Service in the RAF in the 1950s before working

for the Briggs company as a draughtsman. Briggs was

absorbed by Ford, as was Charles. He was involved in

the earlier Zephyrs, but rose to a senior level around

1960. He designed the Consul Capri, the sexy coupe

version of the Consul Classic, which was the bijou UK

replica of the Mercury Monterey, with the backward

sloped rear window shared with the 105E Anglia. The

line of the roof and rear windows of his Capri ended

up in the much more popular later Capri. The cars

based on the Ford Classic were only built for a short

time, as they were both too American and too expensive

to make.

The game-changer was the Mk1 Cortina. Quite large

but light, and with elegant and well-balanced lines, it

was very popular indeed. Charles also designed the

Corsair, a larger and posher version of the Cortina

using the centre section and doors of the Cortina but

This is the car I used to drive to the pub and park beside the Camaro. Respectable enough in its own way.

Charles Thompson’s book of his paintings entitled “Wings” is available by googling it, and the low price

is insulting. His paintings are also not as expensive as they should be.

1962 Thunderbrd: “all ’62 Fords must have round tail lights.” Pic Greg Gjerdingen, Wiki Commons

with new front and back end metalwork, and with the

frontal styling based on the Ford Thunderbird. Most

people never notice that the Corsair is basically a

Cortina, so the adapted design was a success. Charles

also designed the MkIV Zephyr, which had an American

luxobarge look, but also displayed some of the

relative restraint and elegance of the contemporary

Lincoln Continental. (Lincoln and Mercury are both

Ford brands.)

The matter of the Cortina tail lights was fascinating. If

you look closely at the tail styling of the MkI Cortina,

the resolution of the sharp Italianesque lines doesn’t

work well with the fat circular tail lights. On the 1962

Thunderbird, the big circular tail lights work perfectly,

as the whole side of the car is designed to look like a

rocket.

Charles’s Cortina was light, sharp, angular, with a

recurrent theme of subtle triangles, and its tail lights

were wide, flattish triangles with the top angle cut off

to form an almost isosceles trapezoid. The top angle

of this shape followed the flipped-up line at the outer

edges of the bootlid, and the bottom angle matched the

horizontal bumper line. The fins were more suggested

than resolved. He showed me the drawings, and his

version of the tail end certainly looked a lot better. He

bodged the circles into the car’s shape successfully

enough, but it looks very uncomfortable compared to

the sharp Italianesque tail that he originally designed.

The trouble started after he had sent his original Cortina

design to Ford in Detroit, and the message came

back saying all Fords for 1962 have round tail lights.

“That won’t work,” protested Charles. “The whole car

is lightness and angles.”

Back came instructions to do as he was told and put

round tail lights on it.

Not a happy bunny, Charles did as he was told, probably

on the basis that at least if he was the one messing

up the design, he would mess it up less than anyone

else would have done, and he was going to have to

look at Ford Cortinas on the road every day for the

next ten years.

However, he also included what he expected to be a

terminal F*ck You. The three prongs of the round tail

light sections don’t just resemble the symbol of CND,

the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, they were

copied from it.

Charles then sat back and waited to be fired. You

couldn’t have come up with a worse corporate career

suicide attempt than putting a radical socialist symbol

on the back of an American car.

However, he hadn’t understood the ignorance and

insularity of American corporate executives. Most

Americans never notice or see anything that happens

outside America: US news media doesn’t present

anything other than domestic US news even now, and

in the 1960s it was even more so. Calling a purely

domestic sporting event the World Series typifies this

attitude. Also, within the American corporate world,

mediocrity tends to rise: licking the right bums, stealing

credit and sidestepping blame are much more

important than competence.

Everybody in the more developed world thought it

was mildly amusing that Cortinas supported CND, but

the word never reached Detroit, and Charles remained

in his job until he retired early and made a great success

of painting aircraft, ending up as a big noise in

British, Canadian and American aviation art circles.

His work in that field is lovely – equally technical and

atmospheric.

Cortina’s rear end is converted to round tail lights as ordered. Pic Ssu, Wiki Commons

Radical socialist CND symbol is the last

thing you expect to see on the back of a

Ford car.

Pic Tony French, Wiki Commons

Hawk 289

Stuart Clarke’s MGB-based Hawk 289 Cobra replica still carries the 1950s spirit and

quite a lot of the mechanicals of its donor. We review a well-finished example.

The Hawk 289 is quite an expensive prospect, although

the end result is a very high quality car worth

serious money. An example with a 400bhp 351 Ford

Windsor V8 was recently offered for £38,000. It

would also be possible to build a Hawk down to a

budget: the body/chassis assembly is under £7000,

and a good secondhand Rover engine is a suitable and

lighter option.

The use of a donor MGB does help save quite a lot on

the build, as expensive items such as the axles, brakes,

steering column and so on can all be bought as a package

in a rust-doomed MGB for a few hundred pounds,

and they suit the car’s character well.

The choice of an American Ford V8 engine also helps

to keep mechanical rebuild costs reasonable, with

pistons from Summit Racing starting at $120 a set plus

shipping. It’s also still possible to find a period-correct

289 cubic inch V8 engine without breaking the bank,

although the later and more easily available 302 is

essentially the same engine.

Stuart was very taken with the 289 Cobra many years

back, and still has the copy of Classic Cars featuring

the individual Cobra he used as inspiration, replicated

as closely as has been practical.

So is a GRP-bodied car based on an MGB going to be

anything like an AC Cobra, in real terms? The answer

is emphatically yes, the spirit of the Hawk is authentic.

The AC Ace, on which the Cobra was based, was a

Perfect proportions of the AC Ace and early Cobra were executed in Superleggera light steel tubing supporting a hand-formed

aluminium skin: GRP is practical, tough and affordable.

The AC’s timeless proportions have kept it in the top ten most desirable cars for decades. The slim early bodywork enhances

John Tojeiro’s fine body lines.

pretty, quite fast 1950s sports car, which handled well

and was pleasing to drive, within the limitations of a

1950s sports car. It originally used the company’s own

straight six, designed in 1918. AC’s geriatric engine

was finally replaced by a Bristol six, but then Bristol

unhelpfully stopped making car engines. The optional

Raymond Mays-improved Ford Zephyr six was

unpopular with posh AC customers, and the prospects

looked grim. Then a Texas marketer called Carroll

Shelby suggested fitting the small-block Ford V8 with

its light, thin-walled block casting, yielding double the

horsepower and snowballing into a legend as the Cobra

developed into a fat, scary monster with huge 427

big-block motors and bulging wheels and arches.

The Hawk is pretty well the only current replica that

refers to the earlier and more subtle 289 Cobras, with

skinny wheels and flat wheel arches. The suspension

on the AC was by single transverse springs at both

ends, which was okay for a 2-litre six with a light aluminium

body and a light twin-tube chassis, but it was

not really up to dealing with serious power.

The same applies to the MGB’s axles and suspension,

which have the correct and appropriate limitations,

odd though that might sound: but in a 289 Cobra

tribute, we’re looking for a 1950s feel, with limited

but stable grip. Like the AC, the MG’s suspension is

quite good for its time, and even with standard V8

power doubling its performance, it doesn’t have any

nasty habits lurking to bite you – the handling is stable

and progressive, and while it doesn’t grip spectacularly

well, it will give you plenty of warning before it

begins to let go. There’s no snap oversteer or helpless

plough-on understeer as with the rather clumsy and

brutish big-block Cobras, and the small-block V8 suits

both Cobras and MGBs well.

I’ve written several times in recent years about MGBs

converted to US V8 power, and the combo works so

well that my next MG is likely to be a later BGT with

retro chrome bumpers and American power. MGB

version 5.0 gives you two cars in one - a relaxed touring

cruiser, and/or a psychopathic roaring sideways

bruiser if you floor it. The later 302CI Ford engine still

uses the same block as a 289, and unless you’re keen

to have exactly the right period engine number, a 302

is much easier to source and will do exactly the same

job.

Four-speed gearboxes are now rare with Ford V8

engines, and the usual manual gearbox coming with

a Mustang engine would be a T5, a strong gearbox

with well-spaced ratios. With around 250lbs.

ft of torque available for a relatively light car, gear

changing is to some extent optional: you can take

off in second and go straight to fifth, and the car

will grumble sleepily along at 1200rpm.

The Hawk’s chassis and body are both thick and

substantial, and the car’s overall weight will be

similar to an MGB, although the centre of gravity

will be helpfully lower. The light 289/302 V8

engine is actually only slightly heavier than the

old-fashioned and very heavy B-series four, and it’s

also mounted further back in the chassis, so again

the weight balance is quite like the MGB but rather

improved.

The dyno-measured torque from Stuart’s V8 is

275lbs.ft and the bhp is 210, so there is substantial

power available. It’s not too much for the MGB axles,

though, as the Salisbury differential is the same

for the MGB, the MGC and the MGBGTV8, and

provided you avoid violence with the clutch, the

diff will comfortably handle a fairly standard 5-litre

V8. If a much cheekier engine, or animal driving

techniques, prove too much for the MG diff, a

Jaguar XJ6 independent rear end can be bolted to

existing alternative brackets on the Hawk chassis,

and the Jag diff is pretty well indestructible.

The same potential for bolt-on upgrades applies

to the front brakes. The standard MGB brakes

will still lock up the front wheels, as the car still

weighs more or less the same as the standard donor

MG. Bigger brakes do give you more control

and better resistance against fading, so Stuart

elected to go down a traditional British upgrade

route and fitted Princess four-pot calipers. Obviously

the last scrapyard Austin Princess was melted

down and turned into a BMW or a Kia years

ago, but replica Princess calipers are still available

and offer an economical and useful upgrade. For

more aggressive retardation, the American Wilwood

brand offers good value for money.

The Doug Hoyle MGB front suspension upgrade,

available from Hawk Cars, is something that

Stuart will consider once he’s had the car for a

while, but the original MGB suspension is still a

good independent double wishbone setup, even if

the upper wishbone is a lever arm shock absorber.

Unequal length double wishbones are still a very

satisfactory system. The MGB’s crossmember is

discarded in the Hawk, but the rest of the donor

MG’s front suspension and steering are used. There’s

also a Hoyle-designed independent rear suspension

conversion available, or Hawk can supply an anti-tramp

bar and Panhard rod upgrade for the standard

live MGB axle. Again, the sophisticated Hoyle geometry

available from Hawk is definitely an improvement,

but there’s no rush to replace a perfectly serviceable

MGB front or rear axle and suspension.

Stuart’s engineering experience was initially academic

rather than hands-on, and with the help of evening

classes he taught himself to repair cars, from which

it’s only a small step to building them. In fact with

a brand new chassis and body, building a car like a

Hawk is easier than a restoration. Certainly a new

wiring loom grounded to a new steel chassis shouldn’t

give any earthing problems until about 2040.

I don’t think many of us would disagree that this is

a charismatic, beautiful and tempting car. If you like

MGBs and ACs, you will love a Hawk 289. It’s still

a 1950s sports car, but with optionally scary performance.

The next question is whether you could actually build

a car like this. The main thing you need is self-discipline.

You need to commit to doing a little every day,

even if it’s just tidying. If you can do that, the car will

eventually be finished. If not, it will be abandoned,

usually at the 90% stage. As to the skills required,

it’s basic mechanics and house DIY, so if you can put

shelves up properly you can build a good car. A wellmade

product such as a Hawk is certainly a realistic

proposition for somebody who would tackle a big conventional

mechanical task such as replacing the engine

in an MGB. If you are mechanically up to the task of

rebuilding an MGB engine, building a Hawk would

pose no problems at all.

It’s a bit of luck that Stuart’s build has been photographed

and written up in detail, so you can find out

exactly what’s involved if this idea blows your frock

up: we will start running the build story in our next

issue.

Hawk’s website is: www.hawkcars.co.uk

The more you study the sublime lines and curves of the

earlier Ace/Cobra body, the more the 427 starts looking

like a monster. The body can get away with fat arches and

scoops, but it looks best when skinny.

Front on, the Hawk is an accurate replica, apart from fatter radial tyres.

Hawk has been making Cobras for decades, and the moulds

and bodywork are about as good as it gets with GRP cars.

Chrome plated brass brightwork is still as supplied to AC

in 1962. Even the tail lights are still correct.

The cockpit is very inviting, trimmed in black leather and

displaying the full complement of chrome-plated jewellery.

The doors are quite small, so if you’re tall or what used to

be called fat in simpler times, it would be wise to visit Hawk

and check that you fit in the car, although alterations are

possible. A visit is a good idea anyway: say we sent you.

The boot is quite wide, so even with a fat wheel in the

spare bay, there’s a fair bit of room for squashy bags:

continental touring in a Hawk 289 would be a fine way of

spending a week or two.

The T5 is light, slick and strong, a fine gearbox. The ashtray

replicates the original, although it’s doubly useless:

Stuart doesn’t smoke, and the slipstream would tend to

empty it all over the car anyway.

Stuart’s Hawk was issued with an age-related number rather

than keeping the number plate from the MGB. For his

purposes, the number didn’t matter as long as it could use

a black plate.

The Smiths instruments that collectively form the Cobra

dashboard are still available as a set from Caerbont/

Smiths, with electronic tacho and speedo optional. The

steering wheel is still made by Moto-Lita as it was in

the 1960s, so it’s ponderable whether it’s a replica or an

OEM replacement part.

This engine is a genuine 289, although a 302 uses the same

block and is a lot easier to come by. The 289/302 is a good

engine, cheap to overhaul, powerful, reliable and light for its

capacity.

Replica AC ID plate now features the new VIN number of Stuart’s Hawk. Aluminium Cobra rocker covers are

ubiquitous these days.

Transverse spring is a nice visual joke: it’s a fake, the real

suspension is MGB coil springs. It’s got a few people going,

though.

Portraits Stuart still has the magazine with the Cobra feature

that inspired him to build this one. To buy a real 289

Cobra he’d have to sell his house.

Road Trip

A road trip from London to Hungary sounded like an

excellent idea, but ended in an amiable shambles.

“Drive to Hungary? Excellent idea.”

Thus spake your editor, firmly and decisively, but

without really thinking about it. This trip was actually

a long while back, but that tradition lives on.

A Hungarophile mate called Neil Winnington, amiable,

unreasonably tall and sporting size 13 feet, had

suggested a road trip from London to Hungary, to visit

some friends he had out there.

Hungary is somewhere east of Germany, isn’t it? I decided

to find something amusing to travel in and carry

out an extended road test. I was writing for several

magazines at the time, including the British and American

kit car titles. A journo jolly would be the correct

technical term for this trip.

The Chesil Motor Company came up with a car,

one of their excellent Speedsters, based on a Beetle

floorpan and powered by a VW aircooled engine.

This stretches the word “powered” somewhat, but in

WireWheels Magazine, power is an elastic concept.

Chesil’s Speedsters are very well made cars, their only

limitations being related to the Beetle from which they

are authentically built.

There was a lot going on right at that time, and I

squeezed a free week by jamming everything I ought

to have been doing into the preceding and subsequent

weeks.

As you’ll realise, historically the school pupil Ayre

didn’t pay much attention during geography lessons,

and arranged to pop down to Dorset one evening to

pick up the car. Dorset’s a bit past Hampshire, isn’t it?

Well, yes it is. You go down the A3 towards Farnham,

then continue through Hampshire to Winchester, then

you go on past Portsmouth and quite a bit further.

Chesil, it turns out, are virtually in Devon. Dorset

is not a ‘pop’. It’s a fair old trek, particularly when

you’re late and already tired, with an undiagnosed thyroid

condition because your GP’s not very good. Even-

The Hungary Games

CANCELLED

The map is spread out on the bonnet for the first

time. Hungary is waaaay over to the east. Not

going to happen.

Chesil Speedster is an amusing way to travel: it’s a Beetle in a plastic frock, but it looks like a car that

cost $150,000 and then had a $300,000 restoration.

tually there was food, beer, pub chat, and I finally set

off back towards London around midnight, in winter,

in a plastic Beetle, with Beetle aircooled heating and

the tiny windscreen requiring regular wiping with a

frostbitten cloth. There was an hour or two of sleep in

London, then a rather brutal alarm clock got me stumbling

awake for a quick root canal job in Guildford

before picking Neil up in Surrey to drive to Dover for

a meeting with a ferry. Winter channel crossings can

be a bit sporty, and as the puke-spattered ferry lurched

into Boulogne I could see a nice-looking hotel/bar on

the waterfront and decided that day had been going on

for long enough.

The next morning would require some catching up,

but no worries. Early start, top French breakfast with

a bucket of latte and a mountain of croissants and

still-warm baguettes, and we settled the bill and shot

off before the rush hour to get clear of the town. That

achieved, a layby beckoned, offering a chance to get a

grip and plan the day.

For the first time, the map was spread out on the bonnet

of the Speedster.

“Hang on a minute. Here’s us here, and Hungary is

waaaaaaaaaaaaaaaay over there. How the hell far away

is Hungary, Neil?”

“Erm,” said Neil. “I’ve always flown there.”

“How long does that take?”

“Um. Well. About three hours, I suppose.”

“Three hours, at 500mph, would be approximately one

thousand five hundred miles, wouldn’t it, Neil? Three

thousand miles to get there and back?”

“Um, er… oh. ”

Okay then, Hungary was off the menu. We decided

to go and have a look at the Nurburgring instead, and

then turn the rest of the week into an eating tour of the

Ardennes. Or rather, I decided that. The gastronomy of

the French/Belgian border area wasn’t of great interest

to Neil, as he only ever ate chips and drank Coke,

but as the whole trip had been based on Neil’s false

geographic premise, I didn’t feel too guilty about that.

Besides, anywhere near Belgium there are good chips

and there is good mayo. The French will tell you that

the Belgians have square arses from eating chips all

the time, but then the French will tell you lots of rude

things about the Belgians. And about the Germans,

the Dutch, the English… in fact the French are rude

about pretty well everyone but the Scots, with whom

they historically get on very well. The French are in a

permanent sulk because the world language is English

and they think life ought to be carried out in French.

Okay, we were in Boulogne, so where’s the Nurburgring?

300 miles to the east. Fair enough.

Drive up the French coast past Calais and Dunkerque,

not yet swarming with refugees and migrants, and then

head eastwards. We ambled towards Brussels, rich

with EU money and featuring dozens of diplomatic

palaces, with pretty well every car on the road being a

shiny new Mercedes with a taxpayer-funded chauffeur.

No visibly affordable restaurants, so back on the road

and off towards Germany, but with the night spent in

French-speaking Belgium. Flemish-speaking areas of

Belgium are comfy for Brits to visit from a linguistic

viewpoint: the Flemish speak English and French,

because only a few thousand Walloons speak Flemish.

A waitress poses by the Speedster: Neil deploys

cheek and charm and makes many new friends

en route.

Nobody else bothers.

Next day, off to Germany proper. Not super comfortable

there, being unable to speak the language. Most

of my European travels have been in France, or Spain

where I speak enough of both languages to get by: I

don’t claim to speak German at all, despite getting

what seemed like a clear pass with a past GCSE exam

paper in German a year or two back. Multiple-choice,

and standards have dropped by a few percent per annum

for 30 years, to virtually zero. Check out a recent

past GCSE paper, it’s an eye-opener.

Amble on through the Eifel national park on small

roads, actually very pleasant. It turns out that I do

remember enough German to sort out a Gasthaus and

a Zimmer to stay in, and pick out bier, wurst and so on

from a menu. Kartoffel und Coke? Chips? Bratkartoffeln

is chips, okay, gut, dankeschön.

Next day, on we go to the Nurburgring, looking to get

out on the track for some touristenfahrt action in our

pudding-bowl plastic Beetle. Roll up to the entrance to

buy the tickets for a few laps. It’s all shut. What? Corporate

rental day, closed to the public. Bollocks. Wonder

what the corporate company’s shareholders would

say about the huge waste of their money? You can bet

that the shareholders weren’t invited. There wasn’t

even anything going on, the place was silent apart

from some grumpy members of the driving public who

had tried to come out to play on the circuit. Oh, never

mind. Back in the Chesil and splutter off towards the

Ardennes, noted for paté.

I hadn’t previously been to Luxembourg, but you can

Botassart, le Tombeau du Geant and the village

of Frahan. Pic credit Jean-Pol Grandmont

who takes excellent pics of his home turf.

Mediaeval Bruges has canals, which offer an intriguing viewpoint on the mediaeval city.

drive right through it without noticing, really. Aim for

Sedan, then an amiable cruise through the Ardennes

on the small roads, looking for and at little restaurants

in small towns. If you see a place with expensive cars

parked outside, that’s always a good sign. The menu

prices may or may not brutal, but the quality will be

guaranteed. Deliberately asking for a recommended

local wine, even in execrable French, gets most waiters

on side, if you are wandering around rural places

where the English don’t visit much. There are some

magnificent patés in the Ardennes region, presented

with very local pride by small restaurants.

“Un selection de vos patés de votre pays, s’il vous

plait, Monsieur. Et frites et Coke pour mon ami Anglais

ici.”

“D’accord, Monsieur.” Crunchy baguette, salty butter,

top local plonque and a big plate of different patés.

Chips and Coke for Neil.

The Semois river has carved many deep curves in the

landscape, and if you’re just wandering around, the

scenery here is pleasing and inviting. Frahan is pretty,

almost surrounded by the Semois: if they joined the

bits of river up they could have a moat. There’s a national

park area in the Ardennes, but it’s mostly cultivated,

so you wouldn’t really know you were in it.

Drifting vaguely westwards towards the coast, and

Chimay rings a bell: it used to be a famous road circuit,

and it’s worth a visit. It looked abandoned and

dead when we went to look at it a while back, but on

Google Maps it still looks functional. The internet

tells us it is coming back to life again with bike racing,

which is excellent news.

Some of the towns in this area were completely flattened

in WWI, although they’ve been rebuilt looking

exactly the same. It’s interesting to look up at the

walls: occasionally there’s a section with pockmarks

and filled holes, which would have been the only part

of that building left standing in 1918.

Or again in 1945.

As we were in the north of France, Bruges is always

Daft but intriguing 7-litre Mini roadster was a

fine chariot in which to amble around a mediaeval

city taking pictures.

worth a visit. I once did a shoot on a 7-litre Mini in

Bruges, and it was a delight – the city is beautiful in

pretty well any direction you point a camera.

After a few days of ambling, it was time for Boulogne

and the ferry. Over to the coast, then, and the trip

continued south on the Routes Nationales and smaller

roads – it’s no particular fun driving a Beetle-based

car on the French motorways, where you’re either

slower than the trucks, or deaf from the yammering of

the engine if you keep up with them.

Changing down for a roundabout there was a bang,

and no clutch. Stumble round the roundabout in

whatever gear the car was already in, encourage it into

neutral and switch it off. Usefully, a village garage

was visible, so a flat push of a hundred yards or so was

no bother.

I have no idea what a clutch is in French, although I

know what a valve is – soupape – and I know what a

broken valve is – une soupape foutue. (Or, delightfully

in Canadian French, oon spap fuckée.) The French for

a clutch…. no clue.

Something of a revelation happened here. Buy a

new clutch cable for a Beetle? Not possible. Too

old. There have been virtually no parts for Beetles in

France for forty years, other than from specialists. You

can’t generally get parts for old cars in France at all,

because of many rather corrupt scrappage schemes to

make people buy new (French) cars.

Fortunately, rural garagistes are not just new-part

fitters, they are often imaginative and resourceful, and

have to fix farm kit and all sorts of things other than

cars. The garagiste looked for a suitable cable rather

than an obsolete VW part, and found a lift control cable

from a building. Right-sized wire, re-use the same

nipples, no problem. Go and have some petit dejeuner,

come back in a while, it’ll be fine. Another top French

roadside café breakfast, still-warm baguettes and

croissants, grand café au lait, and chips and Coke for

mon ami. Quoi? What?

Oh, he’s English. Il est Anglais.

Ah, d’accord.

The ferry was caught, and as far as I know that clutch

cable is still doing fine.

Speedster courtesy of www.chesil.biz

The centre of Bruges doesn’t have any ugly bits:

you could amble around it all day.

HANDS ON

Mini Marcos

The Mini Marcos is a 1960s British racing car repurposed for budget

driving fun: the editor’s example is a probably unique NOS barn find.

Progress has always been spotty with the Marcos, as

more immediate and more exciting tasks have pushed

it out of the way. It’s also a good illustration of the

wisdom of forcing yourself to do something to or

around a project car every day, even if it’s only tidying

and cleaning. That way the car will eventually be

finished. Whereas if you leave gaps, they can extend

to weeks, months, years. I believe I’ve owned this

Mini Marcos project for about a decade, and it’s been

stalled for most of that. Now there are convertible

Clouds, supercharged Bentleys and a mongrel Cobra

pushing in front of it.

The end of writing for the Mini magazines was also a

demotivator. That came about after a major falling-out

with the greedy publisher. I had written a book about

restoring Minis, and discovered that a deal had been

done behind my back and the book was being given

away free with magazine subscriptions. That was my

Not taking any risks here: the brake master cylinder

is new, and dual rather than single circuit.

wages being given away. There’s sod-all money in

writing books, but much of what little there is comes

when the book is launched. I don’t know why I still

write books: even without pickpockets taking your

Clutch master cylinder is new as well. This going

to end up pretty well a brand new car.

Mini subframe is rebushed, cleaned up and ready

to go in.

Brake calipers are rebuilt, resealed and bolted to

the driveshafts.

Front subframe is trial-fitted to the bodyshell: it’s

a 1970s British component car so measurements

tend towards the approximate.

wages, it pays less per hour than asking people if they

would like fries with that.

I’m not still sulking about that, but the Mini magazines

and other niche titles now pay so badly that it

makes no sense to write and shoot for them. Might

as well write unpublishable novels and unfilmable

screenplays, it would be more fun and the pay is about

the same.

The squeeze on most printed car magazine editorial

budgets has now gone so far that it pays about 10%

of what it did twenty years back: that obviously feeds

back into the quality, value and future of the magazine.

Editors do the best they can with the crumbs that

are grudgingly scattered, but you can see and feel the

Japanese wheels inherited with the Jap-imported

Squeak are race kit, almost weightless but

rather delicate for road use.

budget when you pick up the magazines. That’s why

people read their paper mags in WHSmith – they’re

not worth buying any more.

So with no demand for Mini stories, the Marcos became

even less of a priority.

However, it has pottered on. It’s now at a stage where

most of the pieces had been sorted and were ready to

go, but some of it is now going to have to be re-restored.

Brake and clutch cylinders don’t like being left

unused: the internal surfaces rust. Fortunately they’re

cheap, so even if all the new master and slave cylinders

had to be replaced with a new set, it’s not a big

deal although annoying.

The plumbing in the engine bay goes in before the engine,

as it runs around the bulkhead, and access behind

a Mini engine is very limited.

Making up brake and clutch hydraulic lines is quite

therapeutic, except when you flare both ends and

forget to put the connectors on, which will happen at

a rate that reflects how much attention you’re paying

and how often you have made up lines. Not a big deal,

you just cut off the final quarter-inch, slide the fittings

on and flare it again. You always leave plenty spare, as

piping can be shortened but not lengthened.

Rear suspension is still standard Mini, with

independent swinging arms compressing rubber

cones.

The engine and gearbox assembly is trial-fitted

to the front subframe.

Engine bay viewed from above is a decent size,

less crowded than the Mini engine bay.

Rear subframe is fitted up to the body, just as it is

in a Mini.

The shock towers on the Marcos duplicate those

in the Mini shell, but they’re fibreglass and

can’t rust. They’ve now been drilled out for the

shock bolts.

Steering column is zap-strapped into place for

the moment. It’s at a much more natural low

angle compared the rather bus-like Mini, but

then Marcos didn’t jam four seats, a boot and

an engine into ten feet.

Left side floor and shell, looking forwards.

There’s not much structure to the shell. A rollcage

would be the smart move.

Making the piping curves is quite fun, as you will be

rooting around looking for jamjars, jack handles, toolbox

lids to provide the right profiles to use for bending

the pipes into pleasing curves.

When fitting piping to the car, one of the regular IVA

test failures that’s worth paying attention to is the

spacing of pipe clips. The manual says clips every

30cm, although every 20 cm would work better for

me. There must be no possibility of pipes vibrating

and fracturing, so they need more rather than fewer

clips.

The piping itself must be steel in North America,

Kunifer copper alloy in Europe. The copper alloy

pipes are better as they don’t rust. You can’t use pure

copper piping, it’s too soft and suffers fractures.

The Mini that gave its all to the Marcos cause had

been rust-free, which was very helpful as the rear

subframe was perfect. That really is rare with any

Mini that’s been used at all as the subframes are very

prone to rusting. £300 for a cheap one, nearer £500 for

replica OEM. The front subframes don’t seem to have

any rust traps designed in, and they also tend to get

a coating of oily kak from the engine, which is a fine

thing.

Too many options proved a problem with the Marcos,

as there are three sets of instruments available for

it. The dash is veneered, precut and designed for the

three Mini clocks from the 1970s, which comprise the

speedo with its included fuel gauge, the oil pressure

The rolling shell is now mobile, and it’s more or less an assembly job from here. Weird that the project

stalled at this stage.

This is the instrument set that comes with the

Mini – separate oil pressure and coolant temp

clock, with fuel level and warning lights for indicators,

generator and oil pressure on the main

speedo dial. Simple and effective, and fits the

standard Marcos dash.

Just a reminder of what fun the demonstrator

was. In this shot it’s in Cromer during my annual

UK tour to have a chat and a drinky with all

my UK book and mag editors.

and coolant temp gauges. That’s all you really need,

and the clocks are Smiths, black faced with chrome

bezels, and they’re correct and original and would

look good against the wood. On the other hand, I have

two sets of Auto-Meter instruments, which are good

quality and offer a tachometer and a voltmeter as

well as the other Mini functions. There’s also an even

bigger and flashier set of Auto-Meter clocks, offering

a big tacho with over-rev recall, fuel, coolant temp,

voltmeter and also oil temp and transmission oil temp.

Although come to think of it, you would expect the

engine oil and transmission oil temperatures in a Mini

engine to be the same, as it’s the same oil. There’s still

a Cobra brewing up, so the fancy Ultra-Lite Carbon

set will probably go in the Cobra.

The other point is that this Marcos is unique: it’s a

complete New-Old-Stock Mini Marcos kit, never built

although it was supplied in 1974, and it should really

be completed as supplied.

Yet another choice is the Carbon Fiber Ultra

Lite set I got for the Cobra from Auto Meter,

with the tacho as the main instrument, and

subsidiary km/h speedo, water temp, oil pressure,

fuel gauge, voltmeter, oil temperature and

tranny fluid temperature. I should keep this lot

for the Cobra.

Lagonda

Burps:

misfires and economics

On the other hand, there’s an excellent set of

Auto Meter kit – speedo, tacho, oil, fuel, water

and volts. Which were obtained with this car in

mind.

Memory tacho establishes who over-revved

the engine and blew it up, assuming I let Pete

have a go at slalom. Of course I will, Pete.

These are all Sport Comp, a very popular Auto

Meter choice with highly visible orange needles

against a black face.

Twenty years ago, Colin Gurnsey completed the restoration

of this glorious Lagonda, took it to the Pebble

Beach concours and won his class. He enjoyed both

the process and the victory.

Having won a major prize, the serious pampering and

cotton-bud action was much reduced in intensity, and

although Colin has collected a good few more trophies

along the way, he’s been actively using it as a classic

car. That means driving it regularly in the summer and

not much in the winter except on nice days.

On a day in June last year, the Lagonda almost broke

down – it more or less refused to start. Rather than

being driven to lunch, it was left outside his house and

a few chums were recruited to have a look at it later.

None are mechanics, but all are familiar with the intestines

of classic cars.

Was it a lack of fuel? Disconnect the fuel pump,

switch the ignition on, fuel squirts, not the problem.

Crap in the fuel? No, the fuel is visible in the filter

bowl and is crystal clear. Both carbs having sticky

float problems at the same time? Pretty unlikely,

they’re simple creatures. Old fuel? No, it’s fresh.

Okay, sparks then. The Lagonda has two separate

magneto ignition systems: is it likely that they’ve both

failed at once? As the car inevitably suffers from not

being used very much and being kept in an ordinary

garage rather than being cosseted in a heated and dehumidified

automotive temple, spark issues are more

likely than a fuel fault. Also, if one ignition system has

already gone down, you wouldn’t find that out until

the second one failed. Checking them separately and

regularly would be a good idea.

Sure enough, no spark from the first system, and a

feeble yellow spark from the second magneto. Having

said that, with magnetos you don’t get a very fat spark

at starting revs anyway. A bit of poking and scraping

off superficial connection corrosion and the spark

looked better. The old lady burst into life and all was

well. Colin says that the sparks issue masked another

problem with sticky fuel gum deposits on the float

needles, discovered later. When the problem recurred

during a concours show, he was able to use the onboard

toolkit, strip and clean out the carbs, start the car

and drive it across the podium to collect another First

in Class. The Lagonda has been driven to and from every

event it’s entered, despite having no heater, which

Colin rather regrets: off season, the Pacific Northwest

can be damp and parky. But in the 1930s, only pansies

A car of high quality restored to better than

new condition could make £300,000 more sense

than driving a brand new equivalent.

or showoffs had heaters. Chaps just wore coats and

kept a stiff upper lip, probably frozen stiff.

Get to the point, please.

The point I’m ambling towards is that such a car, well

restored, regularly used and properly looked after,

could probably be driven for twenty years and 100,000

miles without any significant problems at all.

The above was the first breakdown in twenty years,

and it’s well established that a lack of use is a primary

cause of minor breakdowns in classic cars. The cost of

the car’s first breakdown in living memory was some

tinkering, using the car’s on-board toolkit.

Sort out the right classic car in the right condition, and

you really don’t need to bother buying a modern car as

well unless you want one. Modern cars’ reliability is

an illusion: according to the RAC, the overall number

of breakdowns remains fairly constant, although

the proportion of recoveries has soared: a modern

car can’t be repaired by the roadside, but is towed to

a main dealer’s computer and a substantial invoice.

Individual new-car components are more reliable, but

there are thousands more components to fail, leaving

you stranded on the roadside, further back than square

one.

It’s interesting to compare the cost of owning Colin’s

upmarket Lagonda with something modern in the

same league. Is it a valid comparison? Yes, it is. The

Lagonda is a fully practical convertible sports tourer.

It has four seats and some luggage or shopping space,

and it’s fast enough and comfortable enough for long

trips: yes, you could drive this instead of a new car for

daily use. Realistically, a fully restored Pebble Beach

classic is more or less a brand new car anyway.

The cost of buying and restoring this particular car is

a private matter, but Colin started with a basket-case,

and a lot of the restoration work was carried out to

Pebble Beach standards by RX Autoworks in Vancouver.

Their rates are reasonable, but they take as long as

it takes to get everything 100% right. I’m going to say

it would have cost about £150,000.

A Lagonda is a top quality car, so you would be

comparing it with a new convertible Aston Martin or

perhaps a Maserati Granturismo. Buying a VW Bentley

is out, as they’re now the drug-dealer’s ride of

choice. BMW Rolls-und-Royces have Indian-restaurant

sparkly ceilings and possibly even chandeliers by

now; Porsches and Ferraris make you look desperate

for attention, and buying a new Bristol is no longer an

option.

Colin has had his Lagonda on the road for say 240

months. It has cost possibly £40 in oil and filters

every year, but otherwise virtually nothing in repairs.

To be fair, if he had used it for 200,000 miles during

those years, it would have needed some repairs by

now – let’s say £50,000 which would include tyres,

brake linings, clutch plates, a light engine and gearbox

overhaul, and freshened paint.

After lunch, the chums assemble to see if the

collective knowledge can sort out why the

Lagonda won’t run properly.

Nothing is obviously wrong or misplaced or malfunctioning. It’s all still looking very nice, and is

actually all the better for a few years of patina.

Spread out over 240 months, the cost is therefore

£830 a month assuming that he never sells the car.

If he were to sell it, his costs could be less than zero

because he would probably get his money back and

more on such a car, depending on the state of the

economic boom/bust cycle, although Lagondas tend to

cruise above fashion and the inflation and bursting of

Porsche/Ferrari/E-Type price bubbles.

Aston Martin’s DB9 Volante convertible is a new

equivalent of Colin’s six-cylinder Lagonda. Then as

now, Aston Martin-Lagonda’s Rapide is the top of the

line, so looking at a new hand-built Aston compares

like with like.

Leasing a DB9 costs £1500 a month based on three

years, or a lot more than that if you feel you need

a new one every one or two years. Leasing is only

cost-effective as a tax deduction or for people without

capital who need to look rich, whether for business or

personal reasons.

If you buy it rather than renting it, the purchase price

is say £150,000 and then depreciation is 60% over

five years, probably 80% at ten years. That’s assuming

nothing goes horribly and expensively wrong out

of warranty, of course. Fingers crossed. A friend in

England recently bought a DB9 because the high-end

Mercedes sports cars she usually buys had become

so unreliable that a hand-built Aston was more likely

to get her to work, a notion that will please Brit-car

enthusiasts.

I don’t know that a new Aston is going to last for

twenty years, but if it does, the repair costs are going

to be impressive.

No problem with the fuel supply, and no sign

of kak in the fuel filter bowl. So we move on to

the sparks side and start checking out the two

magnetos: they’re doubled up to avoid breakdowns,

which has worked fine thus far.

So it costs £150,000 to own and say £50,000 to maintain

a DB9 for ten years, and maybe £100,000 more

to get twenty years out of it? Or you could invest

£200,000 in owning and running a pre-war Lagonda

for twenty years and then get all your money back and

more when you sell it.

Of course, finding £200,000 might pose a problem,

but the numbers still crunch pretty well the same way

when we’re looking at cars available for 10% of that

£200,000.

£20,000 buys you either a newish German or a driver

MkVI Bentley. Maintenance costs will be comparable

– the Bentley will definitely need regular and competent

maintenance to keep it in good shape, and the

Audi/BMW will yield few but fearsomely expensive

repairs – a water-pump costs £1200. In ten years, the

German will be worth less than its final repair estimate

and will be scrap, but the Bentley will at the very least

hold its value, although it’s much more likely to rise

significantly. It will also improve your mood, and will

become your friend.

You can’t really put a price on that, but even a numerolexic

like myself can see the cost benefits of driving a

classic car compared to a new one. I don’t do new cars

anyway, but I’m looking particularly fondly on my old

Bentley right now.

Let’s just keep this to ourselves, though. When

somebody shows up in a new and shiny collection of

invoices and wants you to admire it, make suitably

supportive noises and keep your patinated period

Bentley or Lagonda key-fob discreetly out of sight.

Senior WW photographer Paul Pannack sends a

photo essay from a small local car show in Sweden.

He’s been living there for a while. There’s a tendency

to assume that Sweden is a cold place, but the summers

can actually be long and hot. Winters used to

be snowy, but not so much any more as the climate

warms.

Sweden is very big on American classics, with the

Raggare culture still strong. This was originally a

1950s anti-establishment movement based around

the rocker/greaser/rockabilly style, a working-class

reaction against Swedish respectability. As ever, these

Alabama in Almhult

cults lose some of their original bite as the decades

amble past, and the current Raggare are all old men,

the sons of the original rebels. I’d hope not to have to

say they’re respectable now, but I’ll find some to talk

to next Swedish trip and report back to you.

The American percentage of the Swedish classic car

fleet is huge: in this case there were something like ten

times as many Yanks* as European cars, which in this

show comprised a few Volvos and a couple of Brits.

The number of daily Volvos driven by Swedes is a

surprise, since with global brands and common components,

Volvos are not really much different from any

One magneto is definitely not doing much, and

the second one is producing a yellow and rather

unconvincing spark. It’s definitely a spark,

though.

In the end the problem recurred, and turned

out to be the float needles sticking due to gummy

kak coming from the fuel, which was then

randomly flooding the engine. Five minutes’

cleaning, fresh fuel and away we go.

It doesn’t get much more wirewheelish than a MkII Jag, although the wires are wider and chromed,

which is more of an American than a Brit approach.

The other Brit is a Mini, although it has something

like 18” wheels rather than 10”, and

there are five wheel studs, so there’s probably

something cheeky and Japanese under that

one-piece GRP front clip.

other modern. It may just be habit - if you buy a car

and you’re Swedish you buy a Volvo by default.

The huge appeal of American cars is odd in view of

the cost of fuel in Sweden, which is usually slightly

worse than the UK prices. 15 Kroner or £1.27 for a litre

only gets you a couple of miles in a big-block, and

Sweden is a big country with many miles in it. Maybe

most of the big Yanks get to car shows on trailers

towed behind diesel cars.

Volvo PV444 in candy apple red with deleted

bumpers. An odd design, as if it couldn’t make

its mind up between the 1940s and the 1960s.

PV444 estate car or wagon, the Swedes

would probably use the American wagon

word. This one is a bit rude, and retains a

Volvo engine although it’s more ambitious

than the original.

Socially, Sweden is very advanced and civilised, with

very good healthcare and social services, paid for

by high taxes, which everybody seems to feel is fair.

However, in general housing is affordable, particularly

out of towns, and an eye-opener for most petrolheads

in the rest of the automotive world is that Swedish car

clubs often have their own clubhouse buildings. That

luxurious option is usually restricted to seriously rich

clubs everywhere else.

Turbo R means the same on a Volvo as it does

on a Bentley.

The Power Big Meet, an annual American-car celebration

in Vasteras, generally exhibits 17,000 cars.

That’s bigger than most American classic car shows in

America. Again, an eye-opener.

There was only one ‘proper’ hot rod at the show. At

their best, these can be entertainingly creative. One of

the amusing things about the modern hot rod fraternity

is that some of them are more snotty about period correctness

than Pebble Beach judges. They seem to have

rather missed the point of rodding, which originally

used to have the exactly same vibe as the Raggare.

One of the delights of this prissy snootiness is that the

obsessive modern rodders despise kit cars, and then

they buy a new plastic Ford Model A lookalike replica

body and a new steel chassis, and a kit of car parts to

assemble as a… well, what would you call it?

“What are you rebelling against, Johnny?”

“Whaddaya got?”

Story

As a teen in the 1970s, I had a Saturday job in a car

accessory shop in Harrow, run by a top man called

George who was one of the last of the original rockers

from the 1950s. He was a colourful and engaging

character, who retained the black leather, the quiff and

the Chuck Berry tapes, although he had also evolved

to Grand Funk Railroad. He had been a truck driver,

until an unfortunate incident. He drove a milk truck

on a regular route, and there was a set of traffic lights

at the bottom of a hill for which he would adjust his

downhill speed to get through the green without losing

momentum.

Unfortunately, somebody changed the timing of the

lights.

There wasn’t much he could do: the milk truck hit the

back of the traffic queue, and mangled a few Anglias

and Austins, and then the milk in the back slopped forward

again and he squashed a few more. He didn’t kill

anybody, but they were all a bit cross, and he thought

it wiser to lock himself in the cab until Mr Plod arrived.

George died fairly young, and he died of excess,

so unlike most old rockers, he kept the faith to the end.

P1800 remains a top sculpture, although the

unpointed fins showed either good taste or

cowardice, not sure which.

Yankees

Yanks or Yankees is still a slightly loaded

word in the States, although not anywhere

else. In a car show in Sweden or Britain, it

just means a Chevrolet or whatever.

In the USA, a Yankee is a Northerner, the

side that won the civil war, or at least the

first round of it. It’s debatable whether the

US civil war is actually over. The southern

Confederates lost the right to own slaves,

and some of them still resent that. The confederate

flag amusingly painted on the roof

of the General Lee in the Dukes of Hazzard

was also waved by the MAGA mob who

attacked the Capitol in an attempted white

supremacist coup. To anybody with brown

or black skin, the Confederate flag looks

like a swastika, and looking at the situation

coldly, that’s reasonable.

American styling

Car body styling reflects what’s going on in the relevant country, and can be revealing about

the state of the economy and culture of each period.

1930s

Depression. Most cars are Model T Fords, utterly functional. Black paint dries faster, so

they’re all black. Duesenbergs and Springfield-built Rolls-Royces are delicious, but most

cars are basic transport tools. They’re also tough as nails, because 90% of US journeys

are on dirt roads.

Volvo four-cylinder B engine is good for astonishing

mileages if the oil is kept fresh.

Another cheeky Turbocharged R installation.

The storming race-developed Volvo estate cars

of the 1990s are cheap enough to be engine

donors these days.

1940s

The first half of the 1940s was occupied by fighting previous generations of white supremacists

in Europe, but the 1946-1950 period saw some marketing-based styling and

modernisation, with bodies that looked unitary although they were still based on heavy

chassis frames.

1950s

The American industrial machine that won WWII now turns to consumer goods. Mainstream

cars are still utilitarian and simple, but the acreage of chrome plating increases

year-on-year. Towards the end of the decade, space-age rocket and jet aircraft imagery

appears as car decoration, and to some extent shapes the styling.

1960s

1970s

The wings and high bonnets left over from previous decades have disappeared, and

the bodywork perched on the still mostly unchanged separate chassis is specified by

marketers. 1961 in particular sees an explosion of excess, with joyfully vulgar fins and

excrescences. Cadillacs have proper rocket fins a foot high. As the decade progresses,

the stylistic hysteria backs off a little, but the enormous acreage of bodywork and the

hugeness of engines keeps expanding.

Excess charges on, with planned obsolescence now literally an art form, and the shame

of being seen in last year’s body styling being used to push huge sales – until 1973 when

the age of virtually free gasoline (36 cents a gallon) stopped dead. The next Mustang was

an ugly little lump with a 2.3-litre Pinto engine.

Two-door Amazon is another pleasing Volvo

design with faultless proportions.

Model A hot rod, big-block Chevy. Americana

is generally not WireWheels material, but the

progression of styling through the decades is

interesting.

1980s

There are no 1980s cars in the Swedish show, apart from a couple of Corvettes with

styling left over from 1969. I suppose that tells you all you need to know about 1980s

American cars.

Two-door 240 also has good proportions. This

one is used for drag racing.

If you get a faint Vauxhall vibe from the original

interior styling, you’re spot on. 1950s

Vauxhalls are shrunken Chevrolets.

Postwar Cadillac two-door, cool enough to

carry off a set of chrome wires although this

one makes do with steels.

Oldsmobile from slightly later, with cool rocket

motif on the bonnet. Not many parts remain

available for this one, at least when it comes to

body and trim.

Yet another ’55 Chevy, with bonnet rockets and

in candy apple red with a gold roof, and looking

good.

Early 1950s Chevy, with a straight six. Parts

are still available, and these are quite economical

and could still be used as a sensible

daily driver.

1955 Chevrolets remain common in the USA

as well as Sweden. You can build a new one

from available new parts.

The 1955, 1956 and 1957 “Tri-Chevies” were

a huge success, and still are. This one looks

resto-rodded.

1958 Chrysler Imperial, reflecting the change

to blended bonnets and overall squareness.

1959 Imperial, with a more aggressive grille

and fins erupting at the back. 1959 was a mad

and overconfident design year.

A Ford Fairlane from probably 1962, going by

the round tail lights. Early 1960s, and while

vast size is still a theme, the late 1950s excesses

have calmed down somewhat.

Plymouth Barracuda, 1966. Each brand usually

had a coupé muscle car variant to make

the more mundane models look sexy by association.

It might be possible to land a small bush

plane on the runway at the back of the Bonneville.

Another Camaro, this time in dragstrip trim.

They’re quite light cars, which helps.

The Fairlane is towing a vintage caravan,

which has been made from carefully arranged

single curve aluminium. Otherwise it would

have cost ten times as much to make.

Pontiac Bonneville design for the second half

of the 1960s. Vast, at nearly 19 feet long, and

with 6.4 litres being the smallest available V8.

Interior is actually quite restrained for a

1960s Yank. Real wood veneer is not an option

in 120° Arizona summers, so the wood is all

fake in American cars. Some leather is used,

but vinyl is more common.

Only one 1964/65 Mustang at the show, which

is surprising. It’s another US classic so common

that you can build a new one from available

resto parts, many of which are astonishingly

cheap.

Late 1960s Camaro. Actually a very attractive

and dramatic shape, powered by the indestructible

and design-fault-free Chevy 350 V8.

Replica or real 1968 Shelby 350GT Mustang.

Rather like Cobras, you tend to assume that if

you see something this expensive on the street

it will be a fake.

Cheeky twin-turbo big-block Chevy 350 in a

next-generation Camaro.

1970s Stingray. The dramatic C3 shape ran

from 1969 to 1982, and the primitive chassis

still looked like that of a boat trailer rather

than a sports car.

Another Corvette, probably 1990s. The chassis

was improved as time went on, but the

basic identity of the car – plastic bodywork,

straight line performance – carried on for

an admirable 67 years until it got a mid rear

engine in 2020.

1969 Buick GS. There have always been attractive

Buicks from away back – they looked

good in the 1920s and 1930s too.

Zundapp two-stroke is the continental equivalent

of a BSA Bantam.

There were some Jap tuner cars there for the

youthful and fashionable.

Second-gen Camaro runs from 1970 to 1981.

Not bad looking, and good proportions, but

it lost the taut and aggressive beauty of the

1967-69 cars.

“ ...the current Raggare are all old

men, the sons of the original rebels.”

1971 Mustang Mach 1. Bigger, heavier, blander,

soggier.

This is what the Swedish countryside looks and

sounds like when there aren’t turbocharged Volvos

screaming through it.

HANDS ON

Not-So-Good Vibrations

Paul got some footage of this car and others fighting the turbocharged Volvos on a

legal street dragstrip: the Yanks say there ain’t no substitoot for cubes, but they’re

wrong. Check it out on the www.wirewheelsmagazine.com website.

Ancient stationary engines are always worth a look. We like the brakes on this one,

to stop it ambling off on its own. Simple chocks would just be boring, wouldn’t they?

A nice 1974 editorial overdrive MGB in BRG,

that came and went a while back. Perfect for

opentop spring and fall ambles through the

Okanagan valley in BC.

Somebody either unaware or foolish had reused

Nylock nuts on the propshaft bolts. A

couple were finger-tight but none had fallen

off yet.

Jackstands or axle stands to stop the car falling

on my head.

Rear wheel drive and 4WD involve propshafts. They

have two universal joints that are universal both in

application and in movement, and they have a defined

life, although it’s a much longer defined life if they

have a grease nipple fitted and a non-lazy owner.

My MGB developed squeaks and a vibration. A new

universal joint in the propshaft cured it.

The symptoms were an increasing vibration under

drive at higher speeds, which went away on backing

off the throttle and on the over-run. That, combined

with a metallic squeaking from the back when reversing,

strongly suggested a failing universal joint on the

propshaft. A quick grovel under the car and a twist of

the propshaft by hand confirmed this, with a slightly

alarming amount of slop. If it wasn’t sorted out, a

total failure could have rendered the car undrivable.

A failed U/J can also be catastrophic: the MGB has a

crossmember that will catch a falling propshaft, but

many older RWD cars have nothing, and if the front

U/J lets go and the propshaft falls and catches on the

ground, it could potentially either pole-vault the car

on to its roof or rip the back axle out. Either of those

events will spoil your whole day.

Following the rules, which say you never put anything

you want to use again such as an arm or a head under