College Record 2013

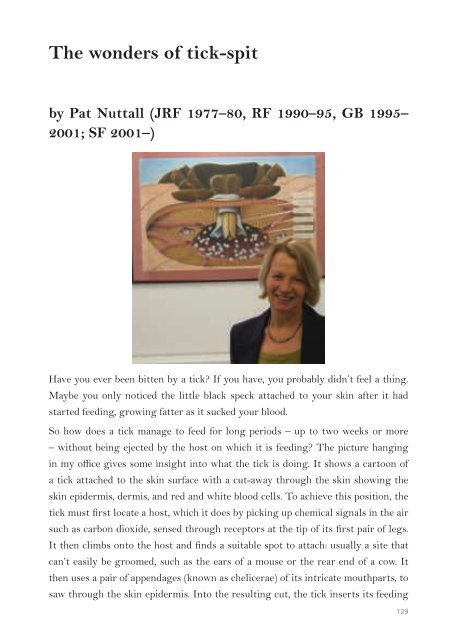

The wonders of tick-spit by Pat Nuttall (JRF 1977–80, RF 1990–95, GB 1995– 2001; SF 2001–) Have you ever been bitten by a tick? If you have, you probably didn’t feel a thing. Maybe you only noticed the little black speck attached to your skin after it had started feeding, growing fatter as it sucked your blood. So how does a tick manage to feed for long periods – up to two weeks or more – without being ejected by the host on which it is feeding? The picture hanging in my office gives some insight into what the tick is doing. It shows a cartoon of a tick attached to the skin surface with a cut-away through the skin showing the skin epidermis, dermis, and red and white blood cells. To achieve this position, the tick must first locate a host, which it does by picking up chemical signals in the air such as carbon dioxide, sensed through receptors at the tip of its first pair of legs. It then climbs onto the host and finds a suitable spot to attach: usually a site that can’t easily be groomed, such as the ears of a mouse or the rear end of a cow. It then uses a pair of appendages (known as chelicerae) of its intricate mouthparts, to saw through the skin epidermis. Into the resulting cut, the tick inserts its feeding 129

tube or hypostome (shown orange in the centre of the picture), which has backward pointing barbs that help secure it in the skin. Just to make sure the tick mouthparts are firmly attached and do not allow any blood to leak out, the tick secretes a milky fluid which solidifies around the hypostome forming a cement cone (grey in the picture). All of this helps explain why it is so tricky to remove a tick once it’s attached. Imagine, though, that this had been a splinter wedged in your skin. First, you would feel a hurtful prick and then your skin would become inflamed and possibly swollen. Why doesn’t this happen when a tick bites? The reason lies in the tick’s large and complex salivary glands. These produce the cement fluid and hundreds of other molecules (proteins, peptides, and small molecules), which are secreted in tick saliva while the tick attaches and then feeds on blood. Saliva molecules have different activities that help make ticks invisible to the host’s protective mechanisms, and keep the blood flowing so they can suck it up. Saliva molecules include anaesthetics, anti-inflammatories, anticoagulants, and immunomodulators. It’s not surprising ticks have been called sophisticated pharmacologists. And it’s all in their spit! 130

- Page 79 and 80: Kumpik, Daniel (DPhil Physiology, A

- Page 81 and 82: Tai, Li Yian (MSc Financial Economi

- Page 83 and 84: Clubs and Societies AMREF Group The

- Page 85 and 86: Quite coincidentally, Jon Rowland a

- Page 87 and 88: time, we have welcomed Catriona Can

- Page 89 and 90: in prosecco kindly provided by the

- Page 91 and 92: continued throughout the year with

- Page 93 and 94: comets and asteroids, have been con

- Page 95 and 96: St Antony’s 3-1, a hard-earned vi

- Page 97 and 98: Karate For many years Wolfsonians h

- Page 99 and 100: included the annual performance at

- Page 101 and 102: your era, but without the dressing-

- Page 103 and 104: translated A Countess in limbo: Dia

- Page 105 and 106: a warm day, and the top seeds looke

- Page 107 and 108: Wolfson/Darwin Day 2013 This year

- Page 109 and 110: students and Fellows - vital for in

- Page 111 and 112: Life-Stories Event The fourth annua

- Page 113 and 114: thank her for her hard work, impert

- Page 115 and 116: Wolfson’s Early Printed Books by

- Page 117 and 118: firm in 1516. It includes a variety

- Page 119 and 120: few lines of text are surrounded by

- Page 121 and 122: Music is Everywhere by John Duggan,

- Page 123 and 124: for the final part, and the Wolfsca

- Page 125 and 126: so, with a little gentle prodding,

- Page 127 and 128: The Death of a King by Martin Henig

- Page 129: I suppose we were a generation lost

- Page 133 and 134: In trying to develop creativity in

- Page 135 and 136: Pawdle across the chumba John Penne

- Page 137 and 138: Common Room, as a space where every

- Page 139 and 140: The Record Adam Reilly proposes to

- Page 141 and 142: Deaths Baldick Robert Julian (GS 19

- Page 143 and 144: Mendoza, Blanca (GS 1980-85, MCR 19

- Page 145 and 146: Beebe, Steven A Business and Profes

- Page 147 and 148: Hodges, Christopher (MCR 2011-) Con

- Page 149 and 150: Sorabji, Richard (MCR 1991-96, SF 1

- Page 151 and 152: 150

- Page 153 and 154: 152

The wonders of tick-spit<br />

by Pat Nuttall (JRF 1977–80, RF 1990–95, GB 1995–<br />

2001; SF 2001–)<br />

Have you ever been bitten by a tick? If you have, you probably didn’t feel a thing.<br />

Maybe you only noticed the little black speck attached to your skin after it had<br />

started feeding, growing fatter as it sucked your blood.<br />

So how does a tick manage to feed for long periods – up to two weeks or more<br />

– without being ejected by the host on which it is feeding? The picture hanging<br />

in my office gives some insight into what the tick is doing. It shows a cartoon of<br />

a tick attached to the skin surface with a cut-away through the skin showing the<br />

skin epidermis, dermis, and red and white blood cells. To achieve this position, the<br />

tick must first locate a host, which it does by picking up chemical signals in the air<br />

such as carbon dioxide, sensed through receptors at the tip of its first pair of legs.<br />

It then climbs onto the host and finds a suitable spot to attach: usually a site that<br />

can’t easily be groomed, such as the ears of a mouse or the rear end of a cow. It<br />

then uses a pair of appendages (known as chelicerae) of its intricate mouthparts, to<br />

saw through the skin epidermis. Into the resulting cut, the tick inserts its feeding<br />

129