Woolfian Boundaries - Clemson University

Woolfian Boundaries - Clemson University Woolfian Boundaries - Clemson University

132 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES of Harriet’s appearance. “Political” because Harriet and John were crucial fi gures in the women’s suff rage movement: John through his activities as an MP and as the author of Th e Subjection of Women (1869) and Harriet through her essay, “Th e Enfranchisement of Women” (1851) and through her profound infl uence on John. So it is notable that in her essay, which was published just a little over one year after women had for the fi rst time voted in Britain, Woolf invokes Harriet as though she is noting a signifi cant lacuna, a gap in the way the struggle for representation is being represented in this repository of national memory. Ultimately, the political and aesthetic senses of representation become thoroughly intertwined in the NPG. Th e very London spaces Woolf traverses in “Pictures and Portraits” would have evoked still-fresh memories of the struggle for the vote. Trafalgar Square had been an important location for pro-suff rage speeches and parades, and in 1914 suff ragettes had entered the NG to slash Velasquez’s Rokeby Venus and the NPG to desecrate Millais’s Portrait of Th omas Carlyle. Notably, the choice of paintings in these acts focused attention to the distinctive rationales underpinning each museum. To attack Venus was to attack beauty itself, while an assault on Th omas Carlyle was also an assault on an early advocate and trustee of the NPG. 7 Carlyle, moreover, had helped to strengthen the ideological grounds for the gallery by stressing the “hero worship” of great men—a view Woolf references and undermines in Jacob’s Room (1922)—as well as portraiture’s importance as a means through which these men might be worshipped. Had Woolf cast her eyes upwards when she failed to enter the NPG, she would have discerned that one of the portrait busts carved in stone above the Figure 5 door belonged to Carlyle (see Figure 5). Th e subject of the struggle for political representation returns us to Kapp’s Personalities. In her essay, as she transitions away from the subject of the NPG to that of Kapp’s art, Woolf casually (but surely very pointedly) notes the disparity between the number of women and men included in the book, implying continuity between its biases and those of the gallery,

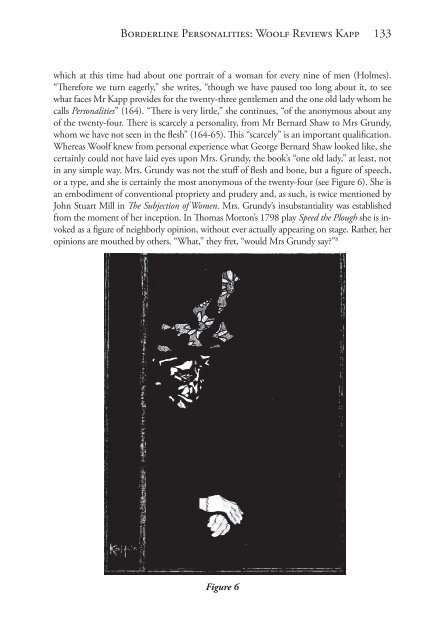

Borderline Personalities: Woolf Reviews Kapp 133 which at this time had about one portrait of a woman for every nine of men (Holmes). “Th erefore we turn eagerly,” she writes, “though we have paused too long about it, to see what faces Mr Kapp provides for the twenty-three gentlemen and the one old lady whom he calls Personalities” (164). “Th ere is very little,” she continues, “of the anonymous about any of the twenty-four. Th ere is scarcely a personality, from Mr Bernard Shaw to Mrs Grundy, whom we have not seen in the fl esh” (164-65). Th is “scarcely” is an important qualifi cation. Whereas Woolf knew from personal experience what George Bernard Shaw looked like, she certainly could not have laid eyes upon Mrs. Grundy, the book’s “one old lady,” at least, not in any simple way. Mrs. Grundy was not the stuff of fl esh and bone, but a fi gure of speech, or a type, and she is certainly the most anonymous of the twenty-four (see Figure 6). She is an embodiment of conventional propriety and prudery and, as such, is twice mentioned by John Stuart Mill in Th e Subjection of Women. Mrs. Grundy’s insubstantiality was established from the moment of her inception. In Th omas Morton’s 1798 play Speed the Plough she is invoked as a fi gure of neighborly opinion, without ever actually appearing on stage. Rather, her opinions are mouthed by others. “What,” they fret, “would Mrs Grundy say?” 8 Figure 6

- Page 96 and 97: 82 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES G. K. Yeates

- Page 98 and 99: 84 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES At another t

- Page 100 and 101: WOOLF AND THE OTHERS AT THE ZOO by

- Page 102 and 103: 88 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES his gaze a s

- Page 104 and 105: 90 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES bankruptcy o

- Page 106 and 107: 92 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES refuses to s

- Page 108 and 109: 94 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES of pesticide

- Page 110 and 111: 96 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Taxonomy in

- Page 112 and 113: 98 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Th e name of

- Page 114 and 115: “CE CHIEN EST À MOI”: VIRGINIA

- Page 116 and 117: 102 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES a statement

- Page 118 and 119: 104 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES pery: “An

- Page 120 and 121: 106 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Woolf’s c

- Page 122 and 123: VIRGINIA WOOLF, ECOFEMINISM, AND BR

- Page 124 and 125: 110 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES with a ‘c

- Page 126 and 127: 112 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES winters’

- Page 128 and 129: 114 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES dominated,

- Page 130 and 131: WOOLF’S TRANSFORMATION OF PROVIDE

- Page 132 and 133: 118 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES appropriati

- Page 134 and 135: 120 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES in her visi

- Page 136 and 137: 122 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES word that d

- Page 138 and 139: 124 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES and Lewis

- Page 140 and 141: 126 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Works Cited

- Page 142 and 143: 128 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES black bars

- Page 144 and 145: 130 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES leap from t

- Page 148 and 149: 134 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Mrs. Grundy

- Page 150 and 151: 136 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Alternative

- Page 152 and 153: PERFORMING THE SELF: WOOLF AS ACTRE

- Page 154 and 155: 140 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES In the proc

- Page 156 and 157: 142 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES would be on

- Page 158 and 159: “WHOSE FACE WAS IT?”: NICOLE KI

- Page 160 and 161: 146 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES for a full

- Page 162 and 163: 148 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES skin, and s

- Page 164 and 165: “MEMORY HOLES” OR “HETEROTOPI

- Page 166 and 167: 152 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES fi rstly th

- Page 168 and 169: 154 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES shaped by a

- Page 170 and 171: 156 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES such as cha

- Page 172 and 173: 158 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES directions,

- Page 174 and 175: 160 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES language, t

- Page 176 and 177: 162 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES work of art

- Page 178 and 179: “THE EVENING UNDER LAMPLIGHT…WI

- Page 180 and 181: 166 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES a model for

- Page 182 and 183: 168 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Humm’s re

- Page 184 and 185: 170 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Figure 6: T

- Page 186 and 187: Afterword INSIDE AND OUTSIDE THE CO

- Page 188 and 189: 174 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES ing before

- Page 190 and 191: 176 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES open future

- Page 192 and 193: 178 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES makes this

- Page 194 and 195: 180 WOOLFIAN BOUNDARIES Notes 1. Fo

Borderline Personalities: Woolf Reviews Kapp<br />

133<br />

which at this time had about one portrait of a woman for every nine of men (Holmes).<br />

“Th erefore we turn eagerly,” she writes, “though we have paused too long about it, to see<br />

what faces Mr Kapp provides for the twenty-three gentlemen and the one old lady whom he<br />

calls Personalities” (164). “Th ere is very little,” she continues, “of the anonymous about any<br />

of the twenty-four. Th ere is scarcely a personality, from Mr Bernard Shaw to Mrs Grundy,<br />

whom we have not seen in the fl esh” (164-65). Th is “scarcely” is an important qualifi cation.<br />

Whereas Woolf knew from personal experience what George Bernard Shaw looked like, she<br />

certainly could not have laid eyes upon Mrs. Grundy, the book’s “one old lady,” at least, not<br />

in any simple way. Mrs. Grundy was not the stuff of fl esh and bone, but a fi gure of speech,<br />

or a type, and she is certainly the most anonymous of the twenty-four (see Figure 6). She is<br />

an embodiment of conventional propriety and prudery and, as such, is twice mentioned by<br />

John Stuart Mill in Th e Subjection of Women. Mrs. Grundy’s insubstantiality was established<br />

from the moment of her inception. In Th omas Morton’s 1798 play Speed the Plough she is invoked<br />

as a fi gure of neighborly opinion, without ever actually appearing on stage. Rather, her<br />

opinions are mouthed by others. “What,” they fret, “would Mrs Grundy say?” 8<br />

Figure 6