VOLUME V: DEFIANCE

The theme of this edition is Defiance, which can be defined as “open resistance and bold disobedience.” With a community as unique and diverse as the one we serve, MA:E Magazine is proud to highlight words and works of all kinds in this edition. Katherine Song in Atlanta, and to Writing as Ourselves. Nellie Shih in Navigating Disconnect. And all of the brilliant photographers who tackled the relative ambiguity of the theme head-on, and imbued it with their own creative visions and definitions of the term.

The theme of this edition is Defiance, which can be defined as “open resistance and bold disobedience.” With a community as unique and diverse as the one we serve, MA:E Magazine is proud to highlight words and works of all kinds in this edition. Katherine Song in Atlanta, and to Writing as Ourselves. Nellie Shih in Navigating Disconnect. And all of the brilliant photographers who tackled the relative ambiguity of the theme head-on, and imbued it with their own creative visions and definitions of the term.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Fashion

WWW. MAEMAG.COM

A New Interest-Based

Magazine for the

APIDA Community

Beauty

Culture

Stories

Photo

Art

Health

Wellness

And

More

Magnetize

APIDA

:

Empowerment

VOLUME V:DEFIANCE

Contents

05

Dearest Reader,

05 Editor’s Letter

06 Skin-deep: In Defiance of Asian Stereotypes

08 Unknowable Thing

10 Defiance

12 Out of Bounds

20 Navigating Disconnect

22 Unbound

28 Spring Showers

30 Atlanta, and to Writing as Ourselves

34 Red

42 Credits

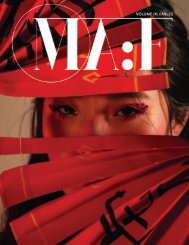

Cover Page | Volume V

| Photographer & Editor

Kat Yang

| Editor & Layout

Christine S Park

| Model

Kat Yang, Debbie Dong

With this edition, we mark a full year

since Zoom calls and the beginning of “the

new normal”. In this year, so many things—

both good and bad—have happened within our

community and in the larger world around us.

Yet, we can’t help but feel so incredibly lucky

that our organization has been able to flourish

in this time of great turbulence.

So today, we write not as MA:E

Magazine, but as four individuals within the

APIDA community who dreamed for greater

representation and creative freedom and saw

an opportunity for it on our campus. Though

we initially connected through our shared

interests of fashion and beauty, in the past two

years MA:E has expanded to be a platform that

encompasses so much more.

When #StopAAPIHate started to

dominate our Instagram feeds and increasing

reports of heinous violence and discrimination

against our brothers and sisters cropped up all

around the country, we struggled with what

action steps we could take. Maybe repost a

couple resource carousels, send out a quick

“we stand in solidarity” story, or put on an artcreating-feelings-venting-donation-matching

event. Ultimately, few of our initial plans

came to fruition as we buried ourselves in

doom-scrolling habits that left us feeling both

overwhelmed and helpless.

It took some time to realize that in times

of pain, there is no “right” thing to do. There

are certainly things that can help, whether it be

by spreading awareness, raising much needed

financial resources, or by simply taking a break

from social media.Possibly the worst thing one

could do is feel pressured to act without taking

the time to honor their own feelings.

So, we took time to rethink our purpose

and mission behind creating MA:E. How it was

meant to become a platform for people just

like us looking for a place where their identities

could be celebrated, where their creativity could

be expressed, and where their stories could be

told. And how at the end of the day, there will

always be a need to elevate the voices of those

who often go unheard, and that there can never

be enough room for them to do so. In other

words, we realized that rather than being a

spokesperson for our community, MA:E should

be a platform to amplify voices that have always

had so much to say.

The theme of this edition is Defiance,

which can be defined as “open resistance and

bold disobedience.” With a community as

unique and diverse as the one we serve, we

are so proud to highlight words and works of

all kinds in this edition. Katherine Song in

Atlanta, and to Writing as Ourselves. Nellie

Shih in Navigating Disconnect. And all of the

brilliant photographers who tackled the relative

ambiguity of the theme head-on, and imbued

it with their own creative visions and definitions

of the term.

For every artist, writer, team member

and contributor, the act of occupying space,

creating, and sharing with the world is defiance.

So with that being said, thank you for allowing

us the time to process, grieve, and heal. We are

so excited to present to you the fifth edition of

MA:E, and as always, please enjoy.

With love,

Anabel Nam, Audrey Ling,

Christine Park, and Katherine Yang

MA:E Co-Founders

Skin-deep:

Written by | Tian Yeung

Illustrator | Michelle Kim

In Defiance of Asian Stereotypes

I could oblige. Many people often argue with me and

minimize the negative effects of this stereotype by saying

that it’s not that bad because it’s a “positive” stereotype.

Well, I disagree. I have felt the pressure of this stereotype

since I was a child, and sometimes I am surprised at the

fact that I didn’t crumble from it. Looking back now, I

also know that if this stereotype didn’t exist, I wouldn’t

have wasted my time on math, something that I didn’t

even like. Instead, I would’ve spent more time on things

that I actually enjoyed: reading and writing. The false

belief that these Asian stereotypes are “positive” is a

main reason why they are still being perpetuated.

Of course, there are many more Asian stereotypes

out there, and it’s impossible for me to cover them all

here. But by now, my hope is that you get the point. So,

to answer the question of how we can stand in defiance

of these stereotypes, other than calling someone out

explicitly, here is an alternative: ask them questions. It’s

no secret that people don’t like it when they are told that

they are wrong. Some may hold on to their beliefs more

stubbornly and even become violent. So, to de-escalate

a situation or avoid having a conflict, ask them why they

said what they said: Why is that funny? What do you

mean? Why do you think that? By asking questions,

they will have to reflect on what they said and doing

so will hopefully lead them to realize the wrongness of

their words. If I could travel back in time to that day in

my chemistry class, I would look Mrs. C in the eyes and

ask her, “What do you mean I need a translator?”

I

often feel like the color of my skin precedes me, and

the stereotypes associated with it define me. And not

without good reasons. You see, the thing about Asian

stereotypes is that they are so normalized, so accepted

by society, that they are usually hidden, brushed aside, or

disguised as positive. Now think about growing up with

these “messages,” not knowing that they are stereotypes,

that they shouldn’t be or don’t have to be true, until you

have inadvertently let them define you. It’s tragic, isn’t

it? So how can we stand in defiance of these stereotypes?

Well, we have to first start with acknowledging what

they are.

Let me take you all the way back to my

freshman year of high school, to an incident that will

unfortunately resonate with many Asian Americans.

There I was, fourteen years old, extremely introverted

and a bit awkward, seated in my chemistry class. The

bell signaling the end of class finally sounded, and as I

was about to leave, Mrs. C, my chemistry teacher who

happened to not be Asian, stopped me. She looked at

me with concern in her eyes and said, “Do you need

a translator for the quiz next week?” As I heard those

words, my heart sank. You see, I didn’t talk much at

school back then because of my shyness, but I was

undoubtedly fluent in English. So, on one hand, I

appreciated the fact that she clearly wanted to help.

On the other hand, however, I was deeply offended

because yet again, due to my appearance, I was seen as

a foreigner. More importantly, her words sent a message

to me: who I am underneath the surface doesn’t matter.

Being so shocked by her words at that moment, I didn’t

know how to reply but to tell her “No, thanks.” As you

can see, this is how accepted Asian stereotypes are.

To drive home the point, here’s another example

of a common Asian stereotype. All my life, I was

assumed to be good at math, and to be honest, I liked

the compliments. So even though I didn’t have a natural

knack for math and didn’t particularly like the subject,

I worked extra hard in my math classes. This way, when

classmates asked me for help on their math assignments,

Why is that funny? What do you mean?

Why do you think that? Why is that funny?

What do you mean? Why do you think

that? Why is that funny? What do you

mean? Why do you think that? Why is that

funny? What do you mean? Why do you

think that? Why is that funny? What do

UNKNOWABLE THING

BY by CIALE ciale

Remember that.

That before you were

Hate and Heartache,

You are soil and starlight--

Possibility incarnate.

-- MORO

I

hear Moro’s words in the shape of my

own voice, filling my brain space with

oxygen and exhaling a prayer that

surrounds me. I feel held by her wisdom as she

thanks me into being. Unknowable Thing is an

original movement meditation based on the

1997 Studio Ghibli classic, Princess Mononoke,

directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Inspired by

Ritual Poetic Drama and choreopoetry (based

in the African continuum), Unknowable Thing

follows (and guides) the coming-of-age story of

the wolf girl, San, exploring her adolescence

with her tribal mother, Moro, and reconciling

her humanity in relation to her biological

mother, Eboshi.

It has been such a generative process for me

as both the playwright and solo performer to

learn how to trust my own work and belong

with my gifts — gifts that my training sought

to stamp out of me. Institutional academia

over-emphasizes intellect and rationale above

embodiment and somatic healing. Now more

than ever, as we become more and more

inundated with Zoom calls, it is harder for

me to drop into my body, to ground myself

from the neck down. I craved to center my

wholeness through movement, breath, and

poetry. To ritualize that which I do not know,

but can feel.

How may we embody language and write movement?

How may we develop an attraction to the unknown?

These questions were so lovingly explored

between me and my collaborators: Samantha

Estrella, Amelia Baumann, and Dana

Pierangeli. Each of us exchanged breath and

co-created at the speed of trust, as Rev. angel

Kyodo williams and adrienne maree brown

would say. Although the process was far from

ideal (as is the case with most creative endeavors

in academic settings), I feel so grateful for the

learning curve to develop my own work and

believe in it, too. Trust is a bodily sensation,

after all.

Unknowable Thing, both the process and the

filmed product, is an invitation for practice:

to breathe more than we think, surrender

more than we resist, and allow more than we

understand.

(Unknowable Thing will be premiering this May

through the Theater and Drama Department’s

2021 Playfest along with 5 other original

solo performances. Photos by Beto Soto @

betosotophoto.)

Photography | Beto Soto

Written by | Priya Dandamudi

Graphic Designer | Summer Nguyen

Defiance

/dəˈfīəns/

noun

: open resistance; bold disobedience.

Defiance

/dəˈfīəns/

noun

: open resistance; bold disobedience.

디파이언스 (n)

:(공개적으로 하는) 반항[저항]

Artwork/Layout | Christine S Park

OUT OF

BOUNDS

ut of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bound

ut of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds out of bound

There is a continuous pressure to be constantly

hard-working. The epitome of going against one’s fear

of not fulfilling one’s expectation is to be carefree. There

is a stigma that if one does not work hard enough, then

they will not do well in the future. This stigma prevents

people to feel the need to care of themselves and let

their minds recharge from the burdens of life.

Photographers & Editors | Anna Cao, Emily Cao

Model | Keri Yang

Layout Designer | Emily Cao

Fashion | Carolyn Zhang

nds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds

nds out of bounds out of bounds out of bounds

NAVIGATING

Written and Illustrated by Nellie Shih

Layout Design by Jenny Suh

Disconnect

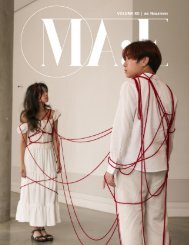

unbound

Combining a traditional element of South Asian clothing called a ‘dupatta,’ typically

worn by women, with Western clothing represents a fusion of the two cultures defies

the idea that Asian Americans can only relate to one culture or the other, and instead

pushes the idea that both can be embraced without taking away from each other.

Photography & Editing | Youmna Khan & Amber Syed

Models | Zayna Syed & Tye Kalinovic

Layout Design | Anna Cao

Video | Lisa Ryou

MICHAEL YEUNG

YAYME

PK MOON

KETAN REVANKAR

Collaboration

JKSN

CROWS

ELOMEL

PK MOON

@SEOUL JUICE

visit @officialmaemag or

https://www.maemag.com

NAMIX

Graphic Designer | Zara Ahmed

Atlanta,

and to

Writing as Ourselves

“I will never write a diaspora story again.”

This is how I end a recent poem of mine, a

grievance about how clumsy and trapped I feel

as an Asian-American writer. Somehow, every

time I reach to incorporate my identity into my

work, I am met with the paralyzing insecurity

that any connection to my intimate experience

is somehow cliché. I can’t write about someone

with the last name Kim, Park, or Lee—that’s

exactly what people expect of me. I can’t write

about the invisibility of existing as an “other”

in predominantly white spaces; people express

that sentiment all the time, more articulately

and with more grace than I can muster. I will

sound bitter, and I will seem strategic, as if I

stretch my cultural experiences just as fodder

for consumption. I feel as if people are tired of

hearing about lunchbox moments or incorrect

name pronunciations, so I take care to carve

my way around “Asian-American tropes.” I

have to write characters who are ethnically

ambiguous. I have to make things universal.

I have to prove to everyone, and above all, to

myself, that I am capable of garnering approval

without using my identities as a crutch. As the

model minority, it seems I am often made to

think of them as a crutch.

These thoughts have always been

familiar and cyclical, to the point where I

began to convince myself that I should no

longer be attempting to write about anything

that I personally have a stake in. I am secure in

being a Korean woman, so there’s no reason to

push myself to engage in that painful digging

that telling our stories requires. My very

privileged experience in this country and I,

what could we possibly contribute? But even

with attempts to numb my brain and jump

through hoops to escape taking on depicting my

likeness, I still craved the representation that

seemed to flow so easily from other sources.

Growing up, any cartoon character with black

hair and ambiguous features was Asian to

me. I remember feeling frustrated that the

TV adaptation of Little Fires Everywhere didn’t

feature Asian women as the main characters,

simply because they had always been Asian in

my head, as the author is, and as I am. The

dissonance was stunning—how could I avoid

writing about my identity like the plague and

then search for reassurance and representation

everywhere else?

Illustrator | Lucy Sun

Written by | Katherine Song

Layout Design | Christine Park

I read the news about Atlanta at one

or two in the morning the following day. It hit

me like a train. I felt the lump in my throat

sink down to my stomach like an anchor,

carrying with it an impossible weight. The

bright light of my screen, displaying invasive

words like “hate crime” and “sex addiction”

that burrowed into my eye sockets. The

grief was physically overwhelming, yet I

could not break my gaze. I doom-scrolled

instead of sleeping that night. I couldn’t stop

thinking about how the killer must have

viewed his victims to commit something so

heinous, each a whole person reduced to a

mere object. Six out of eight of the victims

looked like my family members, my friends,

and me. And in his eyes, we must have

been things, expendable and owing him

something. I was forcefully reminded that

I am not distinguishable to some. I am not

thinking or feeling or autonomous. No, I am

black hair and a body that invites violence.

I am not really alive—not in the sense that

I deserve protection or control over my own

sexuality.Sitting with these thoughts left me

an incoherent mess.

In a thorough search for solace, I found

myself comforted by one thing: hearing and

reading and absorbing how my Asian peers

vocalize their grief and anger. Their ability

to remain articulate and purposeful when

I felt so impossibly reduced was shocking,

inspiring. There were moments when I

wondered if I could ever evade the intensity

of constant objectification and continue to

live as I had been. My community proved to

me that it is possible.

Not too long ago, I wanted to write

ambiguously, in a way that divulged nothing

about my identity. I wanted to be seen as a

good writer, not a good Asian writer. But I

am Asian; I can’t control that my identity is

so visible, something I can never separate

myself from. I don’t want to. It would be

a disgrace to those who never asked to

become symbols of a movement. To those

who become headlines, hashtags, mourned. I

choose to celebrate my identity in one of the

few public ways I can. Writing: as myself, for

myself. To create my own form of reassuring

representation and ensure that members

of my community know that striving for

proximity to whiteness by erasing yourself is

never worth it. Under any guise.

As Alexander Chee wrote, “I could

finally see how tired I was of the idea of

having to pretend to be a white man, or

be like one. Better to catch the energy that

rises when I fling myself at everything I

fear writing.” To reject the premise that I

am something instead of someone, I will

no longer censor myself, nor will I refuse

myself permission to repeat what has already

been said. Why should my writing be made

universal, when my experiences are not? My

characters written as ethnically ambiguous,

when I myself am not? Whose approval could

matter to me more than that of my very own

community, if they are the only ones who

understand what I mean precisely?

Just as I still crave media representation

in a shallower sense, I hunger for more words

written by people who know my history. It is

with their voices that we inch closer to the

truth. Korean reporters who interviewed

Korean massage parlor workers in Atlanta

and divulged the specifics of the shooter’s

racist threat. Asian-American writers who

demanded the media shift their attention to

the victims rather than the killer and his “bad

day.” There can never be enough storytellers

who possess the intimate details. There

can never be enough of us to scream of the

consequences of racist misogyny, to redirect

attention to racialized violence, to declare

these events patterns from colonialism and

imperialism rather than isolated incidents,

to remind that yellow peril supports Black

power, and to condemn the police state that

is killing us all.

Delaina Ashley Yaun. Paul Andre

Michels. And my sisters. Xiaojie Tan. Daoyou

Feng. Hyun Jung Grant. Soon Chung Park.

Suncha Kim. Yong Ae Yue. A whole world

existed in each of them, and these losses

are incomprehensible. We hold them in our

thoughts, and we ask you not to forget.

Personally, I ask you to directly defy the

condition of the violence against them, the

idea that they were not distinguishable. Make

yourself distinguishable. We need to tell our

own stories.

When pictures flash across a screen

They hand us flowers

and give us advice

White carnations are for mourning

take care, be quiet

and keep your head down.

But today from under a shadow,

we demand more light

Red with anger

white carnations in hand

defy obedience

shout our stories

and rise to fight back.

Photography/ Editing | Katherine Yang

Models | Katherine Yang, Debbie Dong

Graphic Designer | Christine S Park

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Sapphira Ching

Duy Anh Vo

PHOTO TEAM

Alice Liu

Anna Cao

Emily Cao

Hanna Dong

Joan Xiao

Keri Yang

Heather Sun

Amber Syed

Jess Kim

Fatema Dohadwala

Jacob Yu

Katrina Stebbins

Nellie Shih

Younma Khan

PRESIDENT PUBLISHER

Anabel Nam

EXECUTIVE EXTERNAL DIRECTOR

Audrey Ling

EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Christine S Park

EXECUTIVE INTERNAL DIRECTOR

Katherine Yang

PHOTO/VIDEO/FASHION DIRECTOR

Michelle Lin

PRODUCT MANAGEMENT DIRECTOR

Fion Lin

PRINT DIRECTOR

Priya Dandamudi

PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR

Sania Farooq

Check us out on Social Media

VIDEO TEAM

Madeline Kim Lisa Ryou

Abby Lee

Jess Kim

FASHION TEAM

Carolyn Zhang Anthony Huynh

Younma Khan

DESIGN TEAM

Summer Nguyen Michelle Kim

Emily Cao

Anna Cao

Jenny Suh

Zara Ahmed

Lucy Sun

PRODUCT MANAGEMENT TEAM

Yilin Fang

Linh Tran

Kimberly Liang Derek Wen

Sapphira Ching

PRINT TEAM

Nellie Shih

Tian Yeung

Katherine Song

PUBLIC RELATIONS TEAM

Stephanie Kim Amber Wei

Christy Yue

instagram.com/officialmaemag

facebook.com/officialmaemag

https://www.youtube.com/channel/

UC-lfPUzpyQLKo56axQq1QkQ

MA:E OFFICIAL WEBSITE

www.maemag.com