AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 6

This issue takes us from the Manhattan home of interior designer Rayman Boozer to the Bronx fashion lab of influencer and entrepreneur, Krystle DeSantos. From our New York launch pad we hop across the water to walk the streets of Cartagena, Colombia, from the ancient architecture of the walled city to its ultramodern skyline. Keeping us entertained along the way we have a roundup of the best podcasts for your ears right now and Camille Simmons has a new cocktail recipe to help us all stay nice and smooth as we make our way into 2021. Later in the issue, It’s a Family Affair begins a new segment as we take our first looks at the AphroFarmhouse project before stepping into the world of surrealist self-portraitist, Fares Micue. Wrapping things up, we’ll continue our journey into the complex of ideas that make up our diaspora before taking a look at some things we could stand to lose as the 21st century finally begins to grow up.

This issue takes us from the Manhattan home of interior designer Rayman Boozer to the Bronx fashion lab of influencer and entrepreneur, Krystle DeSantos. From our New York launch pad we hop across the water to walk the streets of Cartagena, Colombia, from the ancient architecture of the walled city to its ultramodern skyline. Keeping us entertained along the way we have a roundup of the best podcasts for your ears right now and Camille Simmons has a new cocktail recipe to help us all stay nice and smooth as we make our way into 2021.

Later in the issue, It’s a Family Affair begins a new segment as we take our first looks at the AphroFarmhouse project before stepping into the world of surrealist self-portraitist, Fares Micue. Wrapping things up, we’ll continue our journey into the complex of ideas that make up our diaspora before taking a look at some things we could stand to lose as the 21st century finally begins to grow up.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

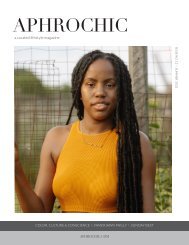

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 6 \ SPRING 2021<br />

FASHION REWIND \ BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY \ AMERICA, IT'S TIME TO GROW UP<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

SLEEP ORGANIC<br />

Avocado organic certified mattresses are handmade in sunny Los Angeles using the finest natural<br />

latex, wool and cotton from our own farms. With trusted organic, non-toxic, ethical and ecological<br />

certifications, our products are as good for the planet as they are for you. Shop online for fast<br />

contact-free delivery. Start your organic mattress trial at AvocadoGreenMattress.com

Thank you. For words of encouragement; for comments and regrams; for DMs, phone calls,<br />

shout outs and well wishes; for thoughts and prayers - the real kind; and for everyone who<br />

took a moment to send a fond thought and some positive energy our way. We felt it. It helped.<br />

And we’re grateful. As much as anything else, thank you for giving us something to do.<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> is a little company with a lot of arms. But in only 6 issues, this magazine has developed into one of the closest<br />

to our hearts. It’s fast becoming what we always wanted our company to be. A platform for new voices, a forum for meaningful<br />

conversation, a place for celebrating the people who inspire us. This magazine gives us space to be the unashamed fans of<br />

our culture - all of our cultures. And we hope it does the same for you. It’s where we root for us. And where we’ve found a lot of<br />

people are rooting for us, too. Knowing that, and having this issue (and the last few), to work on the roughest parts of the last<br />

year gave us something to focus on. And it helped us to remember that life is more than the sum of your problems. With that in<br />

mind, we have an edition to share that we think you’ll love.<br />

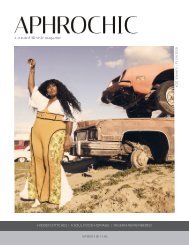

We start this issue off with a cover featuring one of our favorite poets, the amazing Yrsa Daly-Ward. In a shot inspired by<br />

Loraine Hansberry, Yrsa was captured by photographer Poochie Collins in a shoot directed by Tedecia Wint. In addition to<br />

gracing our cover, Yrsa is helping to launch our new literature section, Lit, with a few of her words.<br />

That’s a lot to follow, but we’ve got it covered. This issue takes us from the Manhattan home of interior designer Rayman<br />

Boozer to the Bronx fashion lab of influencer and entrepreneur Krystle DeSantos. From our New York launch pad, we hop<br />

across the water to walk the streets of Cartagena, Colombia, from the ancient architecture of the walled city to its ultramodern<br />

skyline. Keeping us entertained along the way, we have a roundup of the best podcasts for your ears right now and Camille<br />

Simmons has a new cocktail recipe to help us all stay nice and smooth as we make our way into 2021.<br />

Also in the issue, It’s a Family Affair begins a new segment as we take our first looks at the AphroFarmhouse project<br />

before stepping into the world of surrealist self-portraitist Fares Micue. Wrapping things up, we’ll continue our journey into<br />

the complex of ideas that make up our diaspora before taking a look at some things we could stand to lose as the 21st century<br />

finally begins to grow up.<br />

We’ve always said this magazine is a love letter. This month it’s a thank-you note as well. We hope that you enjoy this issue<br />

as much as we enjoyed putting it together. You stuck with us through the worst of what COVID-19 had to offer. And if we forgot<br />

to say it before, thanks.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

SPRING 2021<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Watch List 12<br />

It’s a Family Affair 14<br />

Mood 18<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Fashion Rewind 22<br />

Interior Design // Bohemian Rhapsody 34<br />

Culture // Lit! 50<br />

Food // The Navy Grog 56<br />

Travel // Captivating Cartagena 64<br />

Reference // The Formation of Diaspora 78<br />

Sounds // 12 Podcasts to Catch in 2021 84<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 88<br />

Hot Topic 94<br />

Who Are You? 98

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover photo: Yrsa Daly-Ward. Photographer:<br />

Poochie Collins. Producer: Tedecia Wint.<br />

Assistant: Michelle Bowen.<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Editorial/Product Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

info@aphrochic.com<br />

Sales Contact:<br />

Ruby Brown<br />

ruby@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Poochie Collins<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

Hardley Jeannite<br />

David Land<br />

Camille Simmons<br />

Tedecia Wint<br />

issue six 9

READ THIS<br />

Inspiration leads us to bigger and better things, even in the face of diversity and strife. Each of our book<br />

selections in this issue provide revelations and relationships that have moved us forward, individually and<br />

as a people. The Three Mothers is a first-ever look at the strong and influential mothers of Martin Luther<br />

King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin. Each woman recognized her son's talent and helped guide him<br />

to greatness. A love of food inspired an unusual memoir in Black, White and The Grey - an examination<br />

of a unique friendship and the restaurant that grew from it. And in Begin Again, we're shown how James<br />

Baldwin found inspiration to move forward after the searing years of the Civil Rights movement. Each of<br />

these books provide encouragement to continue on in the "after times" we now find ourselves in.<br />

Black, White and The Grey<br />

by Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano<br />

Publisher: Lorena Jones Books. $28<br />

The Three Mothers<br />

by Anna Malaika Tubbs<br />

Publisher: Flatiron. $28.99<br />

Begin Again<br />

by Eddie S. Glaude<br />

Publisher: Crown. $27<br />

10 aphrochic<br />

Well-traveled home goods, from the rug up.<br />

REVIVALRUGS.COM

WATCH LIST<br />

Women's sports have often been relegated to the back bench, rarely shown in prime time and not often<br />

making the major news. But that's changed in the last few months with some big moves in ownership and<br />

visibility. It started with a dream, the Atlanta Dream to be specific. The WNBA team members decided to<br />

speak out about Georgia politics and to support Rev. Raphael Warnock's run for US Senate, the man who<br />

just happened to be running against Kelly Loeffler, one of the Dream's owners. The team wanted to use<br />

its collective voice to make a difference, and they did. They are now being credited for Warnock's win as<br />

they gave him a major boost by wearing Vote Warnock shirts before each game. Then, just a few weeks<br />

after Warnock's win, former team member Renee Montgomery became a minority owner when the team<br />

was sold to a new investment group. Montgomery is the first former player to become both an owner and<br />

executive of a WNBA franchise. Only two weeks after that decision was announced, three-time Grand<br />

Slam winner Naomi Osaka was named a minority owner in the <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina Courage soccer program.<br />

Forbes’ Highest Paid Female Athlete last year, Osaka said: "It’s an investment in amazing women who are<br />

role models and leaders in their fields and inspirations<br />

to all young female athletes. I also admire everything<br />

the Courage does for diversity and equality in the<br />

community.” Osaka and Montgomery join a small<br />

but growing list of female owners, and an even smaller<br />

list of Black female owners. But they are proving that<br />

women's sports can make a difference, on and off<br />

the field.<br />

Naomi Osaka in her<br />

<strong>No</strong>rth Carolina Courage gear<br />

The Atlanta Dream in their Warnock shirts<br />

12 aphrochic<br />

serenaandlily.com

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

A Healthy Foundation<br />

Sustainability is one of the major buzzwords of the last 20 years, and for very good reasons. As climate<br />

change continues to confront us with the harmful effects wasteful practices have on our environment,<br />

sustainability has become a growing part of conversations about what we make, what we eat, and even<br />

what we wear. But the next big area of concern, especially for our community, is sustainability in the<br />

things that we put in our homes. As we begin the process of designing the AphroFarmhouse, a major part<br />

of our focus is creating as healthy an environment as possible, not only in response to the current crisis,<br />

but in taking a new look at Black homes and the question of what we deserve.<br />

Environmental justice has been a<br />

concern for people of color living in the<br />

United States since the 1980s. By the '90s,<br />

studies were piling up finding that everything<br />

from wage discrimination to<br />

racist practices when selecting sites for<br />

toxic waste facilities were conspiring to<br />

make Black communities the unhealthiest<br />

places in the country. Today, significantly<br />

higher instances of air pollution and<br />

lead poisoning continue to exist in communities<br />

of color across the nation. The<br />

lead-contaminated water crisis in Flint,<br />

Michigan, in 2014 was only the most publicized<br />

incidence of a state of affairs that is<br />

common just about everywhere, but never<br />

gets discussed. Like the more than 1,000<br />

children, many under the age of 6, that<br />

suffered lead poisoning between 2016 and<br />

2018 while living in New York City public<br />

housing.<br />

But creating healthy and sustainable<br />

homes is not simply a matter of dealing<br />

with external racism. Many of the things<br />

we choose to bring into our homes can be<br />

equally dangerous. Furniture made with<br />

composite woods, paint, drapery and<br />

carpeting can all off-gas, releasing volatile<br />

organic compounds (VOCs) into the air<br />

and harming our health. Effects from VOC<br />

exposure, depending on time and sensitivity,<br />

can range from mild eye and throat irritation<br />

to organ damage and cancer. One<br />

of the most concerning sources of VOCs,<br />

because of the amount of time we spend<br />

with them, are our mattresses.<br />

A recent study found that mattresses<br />

containing polyurethane foam<br />

produced significant amounts of offgassed<br />

VOCs despite having been aired<br />

out for at least six months. While the levels<br />

remained below what would be considered<br />

to pose a significant risk, they have<br />

the ability to cause harm over time, especially<br />

in children. But there are organic<br />

options that off-gas significantly less, and<br />

some with almost no emissions at all. In<br />

looking for options in that last category,<br />

It‘s a Family Affair is an ongoing<br />

series focusing on the history of<br />

the Black family home.<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

14 aphrochic issue six 15

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

we partnered with AVOCADO to help us sleep safely<br />

and soundly in our new home. Our new mattress has<br />

been tested for emissions and toxicity. It doesn’t off-gas<br />

harmful chemicals and it’s made with organic certified<br />

wool, and organic certified cotton. We’ll spend roughly a<br />

third of each day having a good night’s sleep on a mattress<br />

that’s healthy as well.<br />

Sustainability is not a term that we often find used<br />

in connection with homes in the Black community. Often,<br />

we think of design more in terms of the effect it will have<br />

on our wallets than what it will mean for our organs.<br />

Because of that, we will often choose options that carry<br />

greater health risks as long as they are less expensive.<br />

And this can result in serious health consequences for our<br />

community. But over the next year, we’ll be advocating for<br />

something different, and will be sharing resources and<br />

tips with you on how to not only design a beautiful home,<br />

but one where foundational materials support the ability<br />

to live well. Because every community deserves quality<br />

homes that support and sustain the health of our families.<br />

The AphroFarmhouse<br />

16 aphrochic issue six 17

MOOD<br />

CROSS COLORS<br />

UNO Artiste Nina<br />

Chanel Abney $20<br />

creations.mattel.com<br />

This spring we’re catching that early ’90s vibe. That<br />

Fresh Prince, Martin, Living Single-type of vibe. Bold<br />

colors and fearless patterns that are all about that oneof-a-kind<br />

mix. From a tie-dye pillow to liven up the sofa<br />

to UNO cards that are literal works of art, this spring is<br />

about embracing those primary hues that make everything<br />

pop.<br />

Vesta 2 Colors Earrings in Lavender $40<br />

rachelstewartjewelry.com<br />

Henry Mask 4-Pack<br />

$49.50<br />

henrymask.com<br />

Batik Square Pillow in Yellow $160<br />

perigold.com<br />

YOWIE Crew in Washed Lime $45<br />

shopyowie.com<br />

18 aphrochic issue six 19

FEATURES<br />

Fashion Rewind | Bohemian Rhapsody | Lit! | The Navy Grog |<br />

Captivating Cartagena | The Formation of Diaspora | 12 Podcasts to<br />

Catch in 2021

Fashion<br />

Rewind

Fashion<br />

Everything Old<br />

Is New Again<br />

To Krystle DeSantos, there’s no such thing as an old<br />

outfit, just one that hasn’t yet caught its second wind.<br />

In a spacious room of her Bronx, NY, apartment that<br />

is equal parts girl-cave and laboratory, the Guyanese<br />

fashion influencer weaves her own special brand of<br />

alchemy. Eras, trends, perspectives and garments<br />

are cast and recast, blended with a skill that would<br />

impress even the best mixologists or DJs.<br />

Photos by Hardley Jeannite<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

24 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

“I blame my mom for this,” she<br />

laughs, neatly sidestepping an inquiry<br />

about her inspiration. But she isn’t<br />

kidding. It’s true that the idea for an<br />

outfit might start with Beyonce’s latest<br />

lyrics or images of Dorothy Dandridge<br />

and Josephine Baker. But the spark that<br />

turns them into distinctive looks still<br />

comes from a little girl watching her<br />

mother and grandmother combine the<br />

pieces they bought with the ones they<br />

created to make magic.<br />

Krystle’s DIY approach to fashion<br />

design honors their example. Many<br />

of her pieces and nearly all of her<br />

accessories are made by her, and<br />

available through Lillian and Joan, the<br />

online fashion accessories shop Krystle<br />

founded in 2012, and which bears both<br />

of their names. But style is more than<br />

a family affair. For Krystle, fashion is<br />

culture, and the island that shaped her<br />

is present in every outfit and every look.<br />

“Guyana’s a very vibrant, very<br />

colorful environment.” she reveals. “My<br />

culture has Indian traditions associated<br />

with it, so I grew up with Diwali, which<br />

is the festival of lights, and Pagwa,<br />

which also uses a lot of color.” Using<br />

her own history as a lens on the wider<br />

legacy of Black women while pulling<br />

from Guyana’s vibrant culture and her<br />

family’s garment-making traditions,<br />

Krystle composes outfits that are<br />

cultural statements all by themselves.<br />

Whether the visual story she creates<br />

is whimsical or historical, surreal or<br />

simply fierce, her message is the same:<br />

Black women the world over are a force,<br />

and they always have been.<br />

Krystle’s take on vintage is light<br />

years away from the ordinary. This<br />

isn’t raiding your mom’s closet for a<br />

few accessories. It’s ready-to-wear<br />

street style with a healthy dose of island<br />

flair and urban attitude. Whether it’s<br />

head-to-toe leopard print or accessories<br />

with a BLM message, Krystle’s creations<br />

are designed to command any stage,<br />

from the wilds of Instagram to the<br />

streets of New York City, proving that<br />

nothing in fashion is ever old, just<br />

waiting to be reimagined. AC<br />

Check out krystledesantos.com and shop<br />

lillianandjoan.com for more from Krystle<br />

DeSantos.<br />

26 aphrochic

28 aphrochic issue six 29

Fashion<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

“I blame my<br />

mom for this.”

Interior Design<br />

Bohemian<br />

Rhapsody<br />

Rayman Boozer's<br />

Work-from-Home Paradise<br />

There’s one on the wall and another on the ceiling. The third is on the bed. His shirt<br />

is number four and the pillow he’s holding to his chest as he speaks is the fifth,<br />

but it’s not the last. There are at least half a dozen patterns in the room, all hailing<br />

from different places, all speaking different languages, telling different stories. On<br />

paper it would be chaos, but in Apartment 48, the live-work loft of Manhattan-based<br />

interior designer Rayman Boozer, they become a chorus, singing with one voice to a<br />

tune that everyone can hear.<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

issue six 35

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

The sense of music in his compositions probably isn’t accidental.<br />

“Jimi Hendrix is one of my icons,” he begins by way of<br />

explanation. “The way he dressed influences my work a lot. I<br />

lean towards the bohemian. I'm really good at mixing patterns,<br />

so you see a lot of pattern on pattern on pattern. Like even when<br />

you feel like there's enough pattern, I'll add one more thing.”<br />

It’s a point of view he’s become known for, but not one that he<br />

imposes on clients. “I can do anything for clients, but at home,<br />

I can really break free. I'll take a couple of patterns or a couple<br />

of colors that you wouldn't think would go together and I'll like,<br />

push them into the same room.”<br />

A soft-spoken man with a quiet demeanor that belies his<br />

bold design style, Rayman’s home is 1800 square feet of things<br />

you might never expect to hear him say out loud. Born, raised,<br />

and educated in Indiana, he admits there may be a difference<br />

between what he thinks and what he says — or at least how he<br />

says it. “It's very popular to be humble in Indiana. That’s just how<br />

I was brought up. So I think that I have a lot of great ideas. But<br />

I think that the way that you present your ideas — you can't be<br />

arrogant. That would never occur to me.” When he first moved<br />

to New York more than 35 years ago, Indiana humility and a lot of<br />

great ideas were about all he had with him.<br />

“It was horrible,” he laughs, remembering the city he<br />

arrived in a week after graduating from Indiana University<br />

with a degree in interior design. “It was not the New York of<br />

the magazines. I was living in Times Square while there was a<br />

recession and it was not very safe. I had no plan, $400 and it had<br />

been a one-way ticket. So I was determined to stay and make it<br />

work.” Years later, it looks like he did.<br />

Stepping into Rayman’s home, the space is quick to make<br />

an impression. Entering almost directly into the kitchen,<br />

avenues to the living area and bedroom sit respectively to the<br />

left and right. The space stretches out in both directions with<br />

only a few walls to obstruct the view, giving visitors a sense of all<br />

that the sizable home holds all at once. The reaction is generally<br />

the same. “Everyone says, ‘wow’,” Rayman reflects. “And I'm not<br />

sure what I did. But I did something with the combination of<br />

colors that hits a note with people.”<br />

Unsurprisingly, Rayman mixes colors with the same<br />

fearless eclecticism that he does patterns. He almost has<br />

to, as the two are in constant conversation in his home.<br />

In the living room, brick walls covered in dark gray paint<br />

separate the lighter notes of the wooden floor and the tin<br />

ceiling — the only remnant from the time before Rayman<br />

moved in. “I think this was a warehouse,” he muses. “It<br />

was built in the '20s.” The different materials in floor,<br />

wall and ceiling create a mix of both pattern and textures,<br />

giving the room a sense of depth. A collection of paintings<br />

and photographs cover the walls as jungle cats make unexpected<br />

appearances on pillows and the space’s area rug.<br />

Every designer knows that a beautiful home has a<br />

beautiful living room. But only the best have two. Hiding<br />

just past the office, Rayman’s second living room emerges<br />

with its own unique color scheme and collection of patterns<br />

— and one special feature that sets it apart: a massive floorto-ceiling<br />

bookcase that dominates an entire wall.<br />

“I really wanted to maximize the space,” he recalls.<br />

So I designed it in 13 pieces and four separate sections but<br />

40 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

connected so it looks like one big thing.”<br />

Moving it in proved a logistical challenge. “I<br />

had to explain it to the people who were going<br />

to build it. Then I had to get it in here.” The<br />

question of one day moving it to a new home<br />

precipitates a quick life decision. “I figure<br />

I'm not going to leave here anytime soon,” he<br />

laughs. It’s an important turn in his relationship<br />

with a place he never planned on calling<br />

home. “I never wanted to live in a loft,” he<br />

confesses. I've been designing them around<br />

the city for probably about 10 years, but I didn’t<br />

see having one.” Instead, what is now a love<br />

affair, began as a relationship of necessity.<br />

Seven years ago, when Rayman was<br />

looking for a home, the only one thing he knew<br />

for sure was that he would move to a place that<br />

could house his business as well as his life. “I<br />

had a store for like 18 years,” he remembers.<br />

“I learned that it's not smart to pay two rents.”<br />

Before his current home, Rayman’s business<br />

operated from his two-bedroom apartment.<br />

But the business grew, and Rayman’s space<br />

needed to grow with it.<br />

In his current home, creating space for<br />

work meant adding walls to the nearly featureless<br />

loft. <strong>No</strong>w the office is a physical manifestation<br />

of work/life balance, a neatly tucked away<br />

area for housing projects and ideas. But just<br />

because the office is where Rayman confines<br />

his work doesn’t mean its the only part of his<br />

home with a job to do. The rest of the home<br />

serves as a walk-in portfolio, demonstrating to<br />

clients what he can do. “They'll say, ‘Oh, now I<br />

see what you mean about mixing French provincial<br />

with American ’60s,’ you know, because<br />

otherwise it doesn't make sense when you say<br />

it out loud.”<br />

Jimi Hendrix isn’t the only influence<br />

from the '60s to make an impact on Rayman's<br />

21st century designs. “It was a time when<br />

things shifted,” he reminisces. “The Civil<br />

Rights movement, hippies, people who were<br />

embracing other people. It was the beginning<br />

of fashion designers looking to the streets<br />

to see what people were wearing. I love bell<br />

bottoms, the Jackson Five and all that stuff.”<br />

Spurred on by the eclecticism of the '60s,<br />

Rayman has spent his life building an impressive<br />

catalog of influences, both real and virtual.<br />

“I love Asian references,” he says, “but I've never<br />

been to Asia. I studied Japanese art in college,<br />

but I feel like it all comes from growing up with<br />

television shows like I Dream of Jeannie and<br />

Gilligan's Island.” Combined with real world<br />

travels to Paris, Florence, and his favorite,<br />

Morocco, it’s a mixed bag with a lot to pull from.<br />

And while the cultural accuracy of '60s sitcoms<br />

is debatable at best, they provided Rayman with<br />

the key to his design superpowers: the power of<br />

fiction.<br />

“I’m always thinking of how I can tell<br />

a story,” he reveals, “but the story is always<br />

fictional.” When designing this apartment, he<br />

thought little about himself, setting the stage<br />

instead for a fictional client. “I said to myself,<br />

‘the guy who lives here, his life is easy. He<br />

doesn't care about things. He just gets stuff and<br />

puts it together.’ ” The one thing Rayman and<br />

his fictional client have in common, however, is<br />

that they absolutely love his bedroom.<br />

Quick to call it his favorite room in the<br />

home, Rayman is equally fast to confess how<br />

little time he spends there. But the lopsided<br />

division of time had no impact on the amount of<br />

design attention the space received. In fact, the<br />

room is very much Rayman’s entire approach<br />

in microcosm, beginning with his enduring<br />

love of art.<br />

“I love photography,” he begins, excitedly<br />

issue six 43

“I'm always thinking how I<br />

can tell a story, but the story<br />

is always fictional.”<br />

cataloging his collection. “I have a really cool<br />

photo by this photographer named Arthur King<br />

from the '40s. There's also a great painting of<br />

scarves in the hallway by this guy, Jerry Garcia,<br />

who was a teacher at Parsons…” Much like the<br />

living room, monochrome photos line the walls<br />

of the bedroom as well as the space above the<br />

bed. But perhaps Rayman’s most innovative art<br />

inclusion is the bust wearing a bandana that sits<br />

by his bedroom window.<br />

“It just became a thing,” he explains. “One<br />

day I put a furry winter hat on it and it looked<br />

really cool. So in summer I gave it a summer<br />

hat. It makes sense if you if you look back in<br />

old magazines from the '60s like, Architectural<br />

Digest. People like Lord Snowden had busts<br />

with necklaces and other accessories.” The<br />

bust sits on a table in front of a set of curtains<br />

that again evoke the designer’s love of Asia and<br />

fiction.<br />

“I love this sort of chinoiserie thing,” he<br />

says of the green table, made in a European<br />

style inspired by China. “I think it's stylish. I was<br />

intentionally trying to be kind of stylish with<br />

it.” The curtains, a similar take on Japanese<br />

culture, touch on an interesting caveat of<br />

Rayman’s fiction-first design style — to come<br />

close to evoking a culture, but not too close.<br />

“It can’t be literally Asian or European or<br />

African,” he says. For Rayman, landing close to<br />

the cultural mark but not directly on it allows<br />

for the feeling of fiction, letting him blend<br />

disparate elements that might not naturally<br />

go together in creative ways because they’re<br />

not intended to be taken literally. “If you can<br />

imagine it then you can pull anything in and<br />

make it into a story and you use what you have.<br />

I always have a story in the back of my mind<br />

that justifies things, and as long as the story is<br />

strong enough, you can put anything together.”<br />

Appreciating Rayman’s design style is<br />

easy. Grasping it, however, requires embracing<br />

the one word at it’s very center: bohemian.<br />

It’s the perfect word to describe his approach<br />

and his home, drawing from a long history of<br />

malleable meanings to become something<br />

that none of those meanings can capture fully.<br />

Finally it becomes a matter of perspective,<br />

which is exactly where Rayman wants to be.<br />

“When I say bohemian, what I mean is the<br />

vibe of the '60s and '70s, like hippies, and how<br />

they layered on patterns, just like one more<br />

thing on top of something. I want my rooms to<br />

feel like that, kind of over the top, but not tacky.”<br />

But for all of its free spiritedness, Rayman’s is<br />

not a style based on breaking the rules, but<br />

on knowing them well enough to bend them.<br />

“There is science to it,” he admits. “It’s not<br />

nearly as random as I make it sound. I think a lot<br />

about what goes together and what works and<br />

what story I'm telling. I'm very conscious of it.<br />

But I want it to feel effortless.” AC<br />

issue six 45

Interior Design

Interior Design

Culture<br />

Lit!<br />

A Word (and a Poem)<br />

with Yrsa Daley-Ward<br />

Words are important. In every corner of the globe and from the beginnings of the<br />

African Diaspora, words have helped to frame our experience, unite our causes,<br />

and shape our future. Iconic creatives and genius intellectuals, many of whom<br />

were both, have used their words to open doors, reveal truths, and push us not<br />

only to think more of ourselves but also to demand more of the world around us.<br />

When we’ve needed to be inspired, we’ve turned to the orators. When we need to<br />

reflect, we go to our writers. But when we need to aspire or, just as importantly, to<br />

heal, we have our poets.<br />

Interview conducted by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Poem by Yrsa Daley-Ward<br />

50 aphrochic

Culture<br />

Yrsa Daley-Ward is the author of the achingly personal works<br />

Bone and The Terrible, she is perhaps best known as the co-writer of<br />

Beyonce’s Black is King. A masterful excavator of the human experience,<br />

most often viewed through the lens of her own, Yrsa has a fascinating,<br />

sometimes terrifying ability to capture our biggest, most<br />

complex and messiest emotions in just a few words. We sat down with<br />

one of our favorite poets to talk about why people need poems, where<br />

the world needs to go post-2020, and the beautiful cycle of breaking<br />

and mending.<br />

AC: What do you feel is the role of poetry in humanity? What<br />

impels us to do it? What does it give us that we can’t get anywhere<br />

else?<br />

YDW: I think poetry has the power to inspire thought, new truths<br />

and to explore those hard-to-touch areas, helping us to further understand<br />

each other. In poetry, we see that we are not alone. Essentially<br />

I see writing a poem as conveying relatable feelings and matter<br />

of the heart in a succinct, often universal tone.<br />

AC: When did you first discover yourself as a poet? Was it<br />

something you accepted immediately? How have you worked to<br />

develop it?<br />

YDW: I have been writing poems for as long as I remember<br />

and have always accepted that I am a writer. I think reading often<br />

develops the craft, allowing myself to be open and curious, allowing<br />

life to surprise me in the way it is bound to. I think the development of<br />

the craft is more about experience than work.<br />

AC: 2020 felt like a year where everything fell apart. If 2021 is<br />

the beginning of rebuilding, where do you think we need to start?<br />

YDW: Falling apart is a beautiful place to begin. As such, we have<br />

already begun. And so we go on, beginning all the time.<br />

AC: Poetry and the arts have always played a central role in all of<br />

our political and social movements. How do you see the shape of the<br />

movement changing after 2020? What can poets do to light the way?<br />

YDW: I think the poet's only commitment needs be to honor the<br />

thing running through them, whatever truth that might be, however<br />

it shifts and manifests. It’s about following the thing, the spark,<br />

the divine inspiration, and not questioning or contriving too<br />

much. The service is to the art, and this will become service for the<br />

people.<br />

AC: Much of your work focuses on the processes of recognizing<br />

oneself through turbulent times. What, ideally, would you like your<br />

readers to learn about themselves as they learn about you?<br />

YDW: To realize we are all more similar than different. Though<br />

our circumstances differ, our fears, our hopes, our dreams are family.<br />

AC: How would you like your work to be received? Or how would<br />

you like to be remembered?<br />

YDW: I want to follow the art, the joy and love of creating, and<br />

remain as true to myself and my humanness as possible. I want to<br />

make work that is understandable and that will help to make people<br />

feel less alone.<br />

issue six 53

Culture<br />

Poem for My Love<br />

by Yrsa Daley-Ward<br />

I know that I love you. You go walking every morning beneath the trees<br />

when much of the city is sleeping and preparing for more of the same; walls,<br />

information, terror, doubt. You tell me that the sky is on a kind of holiday,<br />

deep-breathing, pink, still. You talk about the sun, so low and tender you<br />

can stare it in the eye. The flowers, still showing up for work. I know that I<br />

love you. Everything around us whispers. It is up to us what we hear.<br />

I think that when this time is over and we are almost nearly remembering<br />

all of this, you will be so full up of the raw, living beauty you have so<br />

diligently collected each morning and the world will have turned, heaving<br />

with its newest learnings. I think there is gorgeous anarchy in not knowing<br />

where this will take us. I worry, you worry, but here we are. Right now, all<br />

there is to do is live.<br />

54 aphrochic issue six 55

The<br />

Navy<br />

Grog

Food<br />

Planning Pretty’s Colorful<br />

Cocktail for Spring<br />

Camille Simmons of Planning Pretty is an expert<br />

when it comes to homes. <strong>No</strong>t just what to put in<br />

them to get the look you want, but also what to<br />

do with them once your perfect aesthetic has<br />

been achieved. Entertaining is her specialty<br />

and she’s been quick to point out that the party<br />

doesn’t have to stop just because we’re all stuck<br />

at home. In fact, while 2021 has us all checking<br />

for vaccine appointments between Zoom calls,<br />

a nice soothing cocktail might be just what we<br />

need. Fortunately for all of us, Camille is here<br />

and she’s got it covered.<br />

Intro by Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

Words and recipe by Camille Simmons<br />

58 aphrochic

Food<br />

Growing up in California,<br />

I’ve always been blessed with the<br />

wide availability of citrus fruits.<br />

Neighbors grow them in their<br />

yards and offer free produce<br />

on front porches. But when everyone’s<br />

giving away free fruit<br />

it’s easy to suddenly realize that<br />

you’ve got way more than you can<br />

eat. Well, if the fruit that’s overflowing<br />

your fridge is grapefruit<br />

then the solution is easy - turn<br />

them into cocktails! Grapefruit is<br />

a great juice to use as a base for a<br />

wide variety of drinks including<br />

this tiki favorite, the Navy Grog.<br />

This classic drink works on<br />

two scales, either as a personal<br />

cocktail or made in big batches.<br />

Since we’re all still socially distancing,<br />

I created this recipe for<br />

two. You can make one to share or<br />

keep one for later. Light, sweet,<br />

and colorful, it’s the perfect drink<br />

to help us kick back and relax<br />

while we wait for spring.<br />

The Navy Grog<br />

(TWO SERVINGS)<br />

6 OZ OF JAMAICAN RUM<br />

2 OZ OF HONEY SYRUP<br />

4 OZ OF FRESH GRAPEFRUIT JUICE (APPROX 1 WHOLE GRAPEFRUIT)<br />

1.5 OZ OF FRESH LIME JUICE (APPROX 2 WHOLE LIMES)<br />

SMALL ICE CUBES<br />

EDIBLE FLOWERS OR FRESH HERBS FOR GARNISH<br />

Start by prepping and measuring all the ingredients, then set<br />

aside. Using fresh-squeezed fruit juice boosts the quality of the<br />

drink over pre-packaged juice. Try rolling the fruit on a board before<br />

cutting in half to squeeze. It softens the fruit and makes it easier to<br />

squeeze as much juice as possible.<br />

To make the honey syrup, pour one ounce of honey into a microwave-<br />

safe bowl and heat for 30 seconds. Then add about an ounce of water,<br />

stir, and set aside to cool.<br />

Grab a cocktail shaker or a large mason jar and fill with ice. Pour in<br />

rum, then honey syrup. Add fresh fruit juices. Shake till frothy.<br />

Fill two stemless glasses halfway with ice and pour equal amounts<br />

into each glass. Garnish with an edible flower or herbs. Sit back and<br />

enjoy — you deserve it.<br />

60 aphrochic issue six 61

Food

Travel<br />

Captivating<br />

Cartagena<br />

Jewel of the Old New World<br />

Once the most important seat of Spanish power in the Americas,<br />

Cartagena, known then as Cartagena de Indias or Cartagena de<br />

Poniente (“of the West”), is one of Colombia’s most populous and<br />

visited cities. A stunning mix of natural wonder, intriguing antique<br />

architecture, and contemporary flavor, it’s a place where the<br />

cannons of centuries-old fortresses still overlook the water, and<br />

symbols of imperial power line streets walked by the descendants<br />

of conquistadors, slaves, and indigenous people alike.<br />

Images by David Land<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

64 aphrochic

Travel<br />

Before becoming a Spanish colony, the area had been home to<br />

civilizations since around 4000 BC. Cartagena was founded in 1533 by<br />

Pedro de Heredia, a hot-tempered Spanish noble who fled Spain for<br />

the New World after killing three of six men responsible for disfiguring<br />

his face. According to legend, the city received its name because many<br />

of Heredia’s men hailed from Cartagena in Spain, and the similar bay<br />

of the new colony reminded them of home.<br />

Prior to Heredia, earlier Spanish attempts to occupy the area had<br />

failed. In 1510, Juan de la Cosa, who captained the Santa Maria under<br />

Columbus, died fighting for the land alongside famed conquistadors<br />

Alonso de Ojeda and Francisco Pizarro. Ojeda and Pizarro survived<br />

but failed to establish a lasting colony. Afterward, Spanish interest in<br />

the area faded in favor of already-established territories.<br />

Once founded, Cartagena quickly gained importance. Yet its<br />

poor defenses early on made it an inviting target. Among the many<br />

who attacked the port town was Sir Francis Drake, who in 1586 sacked<br />

Cartagena with 23 ships and 3,000 men, occupying the city and destroying<br />

nearly a quarter before it was ransomed back to Spain.<br />

As a strategically located port, Cartagena was a hub for Spain’s<br />

export of gold and silver and its import of enslaved Africans. Through<br />

the 16th and 17th centuries, slavery became Cartagena’s chief industry.<br />

Yet many of the enslaved escaped, forming walled communities in<br />

nearby areas as staging grounds for raids on the city to rescue newly<br />

arriving slaves. In 1691, the Spanish crown granted official freedom<br />

to the first and most successful of these settlements, San Basilio de<br />

Palenque, making it the first Black community in the Americas to be<br />

so recognized.<br />

Today, the culture of Cartagena holds all of the depth and beauty<br />

of its long and storied history — mixing reverence for its colonial past<br />

with strong influences from the Indigenous and African communities<br />

that shaped it. La Ciudad Amurallada, The Walled City, holds much<br />

of Cartagena’s past, including the Puerta del Reloj (Clock Portal), the<br />

Palace of the Inquisition, and The Church of Saint Peter Claver, the<br />

Jesuit priest who dedicated his life to the care of Cartagena’s large<br />

enslaved population, becoming one of the patron saints of Colombia.<br />

Statues of colonial figures dot the landscape, paying homage to figures<br />

such as Heredia himself and India Catalina, an indigenous woman<br />

kidnapped as a child and raised by the Spanish who aided in Heredia’s<br />

domination of the indigenous communities.<br />

<strong>No</strong>w as then, Cartagena is a place that captivates all who arrive<br />

on its shores. From the ancient grandeur of the Walled City to the<br />

ultramodern skyline of Bocagrande, from its more than 20 beaches<br />

to its extensive culinary scene which, like the city’s inhabitants, is<br />

a complex blend of Indigenous, African, and European flavors. It<br />

is a place where every sight, every sound, and every step holds a<br />

memory. AC<br />

66 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

issue six 71

Travel

Travel<br />

76 aphrochic

Reference<br />

The Formation<br />

of Diaspora, Part 2<br />

Out of Many, Many<br />

From its beginning, one of the key separations between the<br />

African Diaspora concept and the Pan-Africanism that it<br />

was created to replace, was its focus on difference rather<br />

than unity as the most crucial element of the relationship<br />

between the cultures that comprise it. It was to address the<br />

growing sense of difference between Black cultures that<br />

scholar George Shepperson, as well as Joseph Harris, first<br />

introduced the idea of the African Diaspora in 1965. From<br />

there, more voices joined, including British cultural studies<br />

luminary Stuart Hall, to more deeply and eloquently explore<br />

the nature of the distinctions between Diaspora cultures.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Dan FL Creativo<br />

The idea that these cultures were different<br />

was not, by itself, new. Everyone was aware prior<br />

to 1965 that there were differences between<br />

West Indian and African American cultures or<br />

between Black communities that spoke English<br />

and those that spoke French (to say nothing of<br />

those which speak Spanish). But prior to 1965,<br />

Pan-Africanist philosophies largely held these<br />

differences to be more or less superficial variations<br />

imposed over an underlying self that was<br />

essentially African. By the 1980s however, these<br />

differences were increasingly felt to represent<br />

the truest parts of our cultures, placing the<br />

belief in a universally African self in serious<br />

doubt. In particular, Hall’s concept of “Articulation”<br />

helped recast the Pan-Africanist image<br />

of Black cultures around the world, reforming<br />

it as the complex set of interactions between<br />

connected but ultimately distinct entities that<br />

we now know as the African Diaspora. It was a<br />

process that would continue to challenge not<br />

only our shared notion of self, but even the role<br />

of the nation-state in the creation of culture.<br />

Paul Gilroy and The Black Atlantic<br />

One of the most significant theoretical<br />

interventions in the development of<br />

African Diaspora theory came in the early<br />

'90s. A striking new direction taken by British<br />

historian Paul Gilroy, a student of Hall’s whose<br />

early overtures against British ethnocentrism<br />

led him to completely re-imagine the African<br />

Diaspora concept. Gilroy’s 1993 opus, The Black<br />

Atlantic, is a treatise against all essentialist<br />

theories of cultural production — particularly<br />

those that rely on geography as a means of justifying<br />

positions of ethnocentricity. Perhaps<br />

in response to the pervasiveness of “African<br />

American essentialism” within American Black<br />

Studies programs, Gilroy focuses his attention<br />

on W.E.B. DuBois and Richard Wright, two<br />

paragons of African American intellectual and<br />

cultural history. In considering the life and work<br />

of each, Gilroy emphasizes the extended periods<br />

of travel, work, and study abroad that took place<br />

throughout their respective careers. Stressing<br />

the extremely formational influence that<br />

exposure outside of the United States had on<br />

them, Gilroy argues against the idea that their<br />

work or even they themselves should be considered<br />

“African American” in the strictest sense.<br />

In many ways, The Black Atlantic signifies<br />

Gilroy’s continuation of the work of decentralization<br />

as suggested by Shepperson<br />

and furthered by Hall. <strong>No</strong>t only is Africa<br />

removed as the central cog giving meaning and<br />

cohesion to a network of derivative cultures,<br />

it is removed from the area of study entirely<br />

as Gilroy shifts attention to cultural interactions<br />

among the descendants of the displaced<br />

without special regard for the original site of<br />

displacement. By emphasizing the “roots and<br />

routes” of cultural transmission, reinforced<br />

by the constant symbolic imagery of the ship,<br />

which he states, “remained perhaps the most<br />

important conduit of Pan-African communication<br />

before the appearance of the long-playing<br />

record,” Gilroy argues against the nation-state<br />

as the site of ethnically-based cultural essentialisms,<br />

positing instead that it is in the in-be-<br />

78 aphrochic issue six 79

Reference<br />

tween spaces that culture is most authentically<br />

produced. Thus the Black Atlantic is an<br />

amorphous system of relationships rather than<br />

a coherent network of interactions between<br />

monolithically defined states.<br />

The impetus for this dynamically abstract<br />

approach to culture, identity and belonging,<br />

may be found in Gilroy’s earlier works and perspective<br />

as a Black Britain. As he describes in<br />

Ain’t <strong>No</strong> Black in the Union Jack:<br />

Black Britain defines itself crucially as<br />

part of a diaspora. Its unique cultures<br />

draw inspiration from those developed<br />

by black populations elsewhere. In<br />

particular, the culture and politics<br />

of black America and the Caribbean<br />

have become raw materials for creative<br />

processes which redefine what it means<br />

to be black, adapting it to distinctively<br />

British experience and meanings.<br />

Black culture is actively made and<br />

re-made.<br />

Thus in defining the Black Atlantic, Gilroy<br />

is extrapolating what he has already identified<br />

as being the process of cultural creation<br />

and identity formation in his own context to<br />

the wider diaspora, itself the evolving result<br />

of a series of ongoing cultural interactions. In<br />

the process, Gilroy assumes a position of “anti-anti-essentialism”<br />

– one which views culture<br />

neither as, “a fixed essence, nor as a vague and<br />

utterly contingent construction to be reinvented<br />

by the will and whim of aesthetes, symbolists,<br />

and language gamers.”<br />

The Black Atlantic drew passionate<br />

responses, both positive and negative. In return,<br />

it provided scholars with such fertile ground<br />

for consideration and debate that well into the<br />

21st century that Gilroy has remained, “the one<br />

theorist cited in almost all recent considerations<br />

of the [African Diaspora],” according to<br />

Edwards. As a result, the term, “Black Atlantic”<br />

has gained such currency that it may one day<br />

rival “diaspora” for its multitude of uses and<br />

definitions. Branching out from its own specifically<br />

Diaspora-focused roots, the website of the<br />

Tate museum defines the Black Atlantic as, “the<br />

fusion of black cultures with other cultures from<br />

around the Atlantic.”<br />

Minding the Gap<br />

Following the impact of The Black Atlantic<br />

there have been continued attempts to define<br />

difference within the African Diaspora concept.<br />

The 2001 essay The Uses of Diaspora by Brent<br />

Hayes Edwards examines the history of the<br />

concept in the hope of offering a handle with<br />

which to grasp the rapidly multiplying applications<br />

of the term. Drawing heavily from Hall’s<br />

Articulation and Derrida’s use of Differance,<br />

Edwards offered his own intervention into the<br />

ongoing conversation with Dècalage, meaning<br />

literally “gap,” “discrepancy,” “time-lag,” or<br />

“interval.” Dècalage, Edwards posits, is the<br />

substance that holds together Hall’s articulated<br />

notion of diaspora. As he explains:<br />

Any articulation of diaspora…would<br />

be inherently décalé or disjointed by a<br />

host of factors. Like a table with legs of<br />

different lengths, or a tilted bookcase,<br />

diaspora can be discursively propped<br />

up (calé) into an artificially “even” or<br />

“balanced” state of “racial” belonging.<br />

But such props, of rhetoric, strategy, or<br />

organization, are always articulations<br />

of unity or globalism, ones that can be<br />

“mobilized” for a variety of purposes<br />

but can never be definitive: they<br />

are always prosthetic. In this sense,<br />

décalage is proper to the structure of<br />

a diasporic “racial” formation, and its<br />

return in the form of disarticulation—<br />

the points of misunderstanding, bad<br />

faith, unhappy translation—must be<br />

considered a necessary haunting.<br />

Thus the articulation of diaspora, by its very<br />

nature, creates a series of gaps which function<br />

not only as distinctions between cultures, but<br />

as the repository of all that cannot be translated<br />

from one culture to another. Edwards uses the<br />

image of joints in the body to present décalage as<br />

that which enables the “two-ness” of the joint –<br />

the means of difference within unity.<br />

The Same Coin: Unity and Difference<br />

The fundamental point of departure<br />

between Pan-Africanism and Diaspora is<br />

whether the “truth” of Black cultures is found<br />

in their commonalities or their distinctions.<br />

Pan-Africanism endorsed unity as a matter<br />

of cultural expedience and political necessity.<br />

And as the need for international Black political<br />

activity was thought to be disappearing, Diaspora<br />

began to emphasize difference. Certainly there<br />

are strong points to be made for both. The<br />

political function of establishing an ideology<br />

of sameness between Black cultures globally,<br />

to whatever level of success, is undeniable. At<br />

the same time, earlier parts of this series have<br />

explored the fact that the African diaspora is not<br />

comprised of groups of people dispersed from a<br />

single nation but of groups dispersed from many<br />

nations and to many nations, wherein the unique<br />

processes of history forged not a single group’s<br />

reinterpretation of their former culture, but new<br />

cultures for new peoples formed in different<br />

measures out of the cultures of the oppressed,<br />

the oppressors and everyone they met along<br />

the way. That there is as much that distinguishes<br />

these cultures as unites them is inevitable.<br />

But before we choose sides between universal<br />

sameness and uncrossable difference, there are a<br />

few points to examine.<br />

First, we should consider whether any<br />

argument for unity still remains. The political<br />

impetus for emphasizing international unity<br />

among Black people at the time of Diaspora’s<br />

introduction was, in fact waning. Pan-Africanism<br />

had largely accomplished the goal of liberating<br />

African and Caribbean nations from<br />

colonial rule. However liberation did not necessarily<br />

mean equality, particularly for internally<br />

colonized populations in The United States and<br />

elsewhere. As cultural collaboration eclipsed<br />

political cooperation as the primary form of interaction<br />

for the Diaspora, deeper and more<br />

pervasive issues continued to exist.<br />

Among the many things that 2020 has tried<br />

to show us has been the clear fact that racism<br />

and oppression continue to shape and even end<br />

Black lives around the world. But 2020 not only<br />

highlighted the problem, it demonstrated the<br />

potential for political cooperation between international<br />

Black communities. The Black Lives<br />

Matter Movement exploded in 2020, becoming<br />

a global movement as the deaths of George<br />

Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police<br />

sparked massive protests around the world.<br />

80 aphrochic issue six 81

Reference<br />

Inspired by the American movement and similar<br />

incidents in their own countries, activists such<br />

as Assa Traoré and Djamila Ribeiro have brought<br />

attention to the problems of racism and police<br />

violence in places such as Australia, France, and<br />

Brazil as well as Nigeria. In considering unity<br />

therefore, there remains, not only the cultural<br />

basis but an ongoing need.<br />

Still the question remains. Unity or difference?<br />

Are our truest selves are found in our<br />

points of overlap or divergence? Only it turns<br />

out that this isn’t really much of a question,<br />

because the two are not mutually exclusive.<br />

Unity presupposes difference. In the<br />

absence of difference there exists only a single<br />

whole, of which unity is a prerequisite. This is<br />

true whether discussing a single human body<br />

or humanity as whole. The point of difference<br />

between any two forms is perforce the<br />

point of unity, if it is to exist, because prior to<br />

difference, unity is not possible. Therefore a<br />

diaspora, like every other cultural category,<br />

must be an articulation — a knitting together of<br />

distinguishable bones, because if dispersal had<br />

not differentiated our cultures then diaspora<br />

could not unite them.<br />

So What?<br />

Between the two poles of this argument, the<br />

question is primarily one of emphasis. There are<br />

things that Diaspora cultures have in common<br />

and things that are unique to each. Neither can<br />

be said to exclusively house that which is truly<br />

or essentially us because what we are, regardless<br />

of which culture we come from (often more<br />

than one), is a function of both things together.<br />

Strip everything that is unique from any Diaspora<br />

culture and what remains will not be a pristine<br />

version of an ancient African original. Yet if we<br />

define ourselves only by our distinctions, we<br />

could easily lose sight of each other.<br />

Arguably, this was the case when, in 2015,<br />

British-born, Nigerian journalist Zipporah<br />

Gene penned the article, “Black America, please<br />

stop appropriating African clothing and tribal<br />

marks.” Targeting the incorporation of various<br />

African religious and cultural symbols in the<br />

fashion choices of African Americans attending<br />

AfroPunk, the article cuts a wide swath by<br />

asking the question, “Can Black people culturally<br />

appropriate one another?” deciding ultimately<br />

that we can and, at least in the case of African<br />

Americans, we do.<br />

While Gene’s argument garnered widespread<br />

response at the time, the sentiment itself<br />

was not new. In 1995, Nigerian scholar, Olufemi<br />

Taiwo published, “Appropriating Africa: An<br />

Essay on New Africanist Schools.” In his introduction,<br />

the relationship of African Americans<br />

to Africa is reduced to Africa, “[serving] generations<br />

of Americans on African descent as<br />

a beacon of inspiration in the face of incredible<br />

odds…,” and African Americans, “[seeing] in<br />

Africa and its history, such as they understand it,<br />

a source for narratives and forms of socio-political<br />

discourse to counter the racist denials of<br />

African contributions to…United States history<br />

and civilization.”<br />

The argument of appropriation from both<br />

Gene and Taiwo insists that African Americans<br />

are accessing cultures that they have no connection<br />

and therefore no right to. Looking at<br />

the combination of symbols in the dress of any<br />

one AfroPunk attendee, Gene calls the result,<br />

“a hodgepodge, a juxtaposition.” And while to<br />

her “it screams ignorance and cultural insensitivity,”<br />

violating what she describes in another<br />

article as a strict covenant among Africans to<br />

remain within their specific cultural boundaries,<br />

she is perhaps missing the internal logic that<br />

for a person of any Diaspora culture, “a right<br />

mess of [African] regional, ethnic and cultural<br />

customs,” is exactly what we are. To pare down<br />

that connection to any one location or ethnicity,<br />

even if confirmed genetically, would be to deny<br />

all the rest of what we are culturally, severing<br />

every other tie to the continent and to our own<br />

unique histories.<br />

Gene’s argument not only dismisses the<br />

connection of Diaspora cultures to African<br />

symbols, it forgets the history of figures such as<br />

DuBois and Nkrumah collaborating to introduce<br />

kente cloth as an international fashion trend<br />

specifically to foster a sense of global Black<br />

unity. Similarly Taiwo ignores the history of<br />

collaboration between African, American<br />

and Caribbean communities throughout the<br />

colonial period by casting the relationship as<br />

a one-way syphoning of meaning — African<br />

Americans taking from Africa that which they<br />

don’t understand to provide that which they<br />

don’t have. This series has hopefully shown, at<br />

least in the smallest part, there was and is a little<br />

more to it than that.<br />

Both cases demonstrate, as Gilroy<br />

might attest, the dangers of geographically-based<br />

cultural essentialisms. Fellow Black<br />

Brit Zipporah Gene makes a particularly<br />

interesting argument in that regard. Gilroy<br />

describes Black British culture as defining<br />

itself, “crucially as part of a diaspora,” actively<br />

making and remaking itself out of the raw<br />

cultural material provided by Black communities<br />

in the Americas and Caribbean. By the<br />

rules of appropriation Gene sets down, that<br />

culture would be either completely impossible,<br />

or guilty of appropriation on a massive scale.<br />

More specifically, these examples show<br />

how diaspora’s emphasis on difference can<br />

come at the cost of recognizing our innate connection,<br />

causing us to misrecognize moments<br />

of cultural intersection as attacks on cultural<br />

soverignty. To deny ourselves these connections<br />

would be tragic, culturally, while at the same<br />

time causing us to miss important opportunities<br />

to work together across boundaries on issues<br />

that affect us all. This does not absolve African<br />

Americans or members of any Diaspora culture<br />

of the important responsibility to educate<br />

ourselves on the meanings of the cultural<br />

artifacts of any other Diaspora culture, but it<br />

does draw an important distinction between interpretation<br />

and appropriation.<br />

The shift from Pan-Africanism’s underlying<br />

African self to Diaspora’s focus on cultural<br />

specificity was a massive shift in how Black<br />

people around the world understood themselves<br />

in relationship to one another. With<br />

scholars such as Hall, Gilroy, and Edwards<br />

among many others, leading the way it paved the<br />

road to the rich, complex tapestry of cultures<br />

that we enjoy today as the African Diaspora. But<br />

there must be balance, because left unchecked<br />

that focus can lead to a place where difference is<br />

all we have and diaspora devolves into a series<br />

of competing ethnocentrisms, which to be fair,<br />

has always been a concern. But if neither unity<br />

nor difference are, by themselves, the defining<br />

characteristic of the African Diaspora, it begs<br />

the question, what is? AC<br />

82 aphrochic issue six 83

Sounds<br />

(POP)CULTURE/SOCIAL ISSUES<br />

Brain Food<br />

12 Podcasts Catch to in 2021<br />

Before 2020, podcasts were the ultimate entertainment for the multitasker. Listening in transit,<br />

at the gym, or while busy at home made podcasts a liminal mode of entertainment, keeping us<br />

company during our tasks, but not necessarily taking all of our focus. Despite the 2020 lockdowns,<br />

the pauses on work commutes, and gym sessions, podcasting not only remained relevant, it increased<br />

in popularity. What we learned in 2020 is that listening to podcasts can be a focused activity; an<br />

intimate engagement with the stories and advice that hosts want to share with their audience. While<br />

podcasting platforms and audiences weren’t necessarily diverse at its start, the number of Black<br />

listeners and content creators is on the rise. In a time of sensory overload, of tumultuous news and<br />

the exhaustive everyday, podcasts centering on the Black experience can be a space of meditation,<br />

healing, laughter, and community. This month, we’re taking a moment to showcase an array of<br />

podcasts created, hosted, and produced for Black audiences. Out of the overwhelming (and exciting!)<br />

number of great Black podcasts, these were chosen for their excellent reporting and journalism, the<br />

expertise of their hosts, and their ability to engage the listener with rich storytelling and provoking<br />

conversation. Here is <strong>AphroChic</strong>’s Podcast Playlist for 2021.<br />

Words by Ruby Brown<br />

It’s Lit! features weekly<br />

interviews with Black authors,<br />

discussing their work and their<br />

inspiration. Hosts Danielle<br />

Belton and Maiysha Kai, two<br />

accomplished writers, dive<br />

deep into Black literature and<br />

broader cultural experience.<br />

podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/<br />

the-root-presents-its-lit<br />

Named a 2020 Pulitzer Prize<br />

Finalist in Audio Reporting,<br />

Ear Hustle tells stories from<br />

inside and outside of prison,<br />

interviewing individuals about<br />

their experiences in prison and<br />

their lives before and after<br />

incarceration.<br />

earhustlesq.com/listen<br />

Code Switch was named Apple<br />

Podcast’s Show of the Year for<br />

2020. Since its start in 2016,<br />

Shereen Marisol Meraji and<br />

Gene Demby have hosted this<br />

weekly hub for POC journalism<br />

and news.<br />

npr.org/sections/codeswitch/<br />

1619 is a five-episode<br />

audio series published for<br />

the 400th anniversary of<br />

the beginning of American<br />

slavery. Nikole Hannah-Jones<br />

hosts this exploration into<br />

the origins of Blackness and<br />

the history of enslavement.<br />

nytimes.com/2020/01/23/<br />

podcasts/1619-podcast.html<br />

Strange Fruit provides a<br />

perspective on politics, pop<br />

culture and the Black queer<br />

experience. Dr. Kaila Story and<br />

Jaison Gardner host and bring<br />

listeners to the intersection of<br />

race, sexuality, and gender.<br />

npr.org/podcasts/440577316/<br />

strange-fruit<br />

Resistance was produced in<br />

response to the protests of the<br />

summer of 2020. Host Saidu<br />

Tejan-Thomas Jr. confronts<br />

the feelings of hopelessness<br />

and hopefulness surrounding<br />

police violence and the Black<br />

Lives Matter movement.<br />

gimletmedia.com/shows/<br />

resistance<br />

WELLNESS/ADVICE<br />

DESIGN/ART<br />

Hosted by licensed<br />

psychologist Dr. Joy Harden<br />

Bradford, Therapy for Black<br />

Girls is a weekly podcast on a<br />

mission to destigmatize mental<br />

health issues and make therapy<br />

accessible for Black women.<br />

therapyforblackgirls.com/<br />

podcast/<br />

Truth be Told is an advice show,<br />

comforting and invigorating,<br />

with a variety of topics covered<br />

weekly by host Tonya Mosley<br />

and her guests.<br />

kqed.org/podcasts/truthbetold<br />

Registered dietitian<br />

nutritionists, Wendy Lopez and<br />

Jessica Jones, host this weekly<br />

podcast centering on food<br />

and wellness. Food Heaven is a<br />

space to learn about intuitive<br />

eating and how to incorporate<br />

self-love into your healthcare.<br />

foodheavenmadeeasy.com/<br />

podcast/<br />

Besides the amazing design<br />

talent showcased by a<br />

different guest every week and<br />

the equally impressive host<br />

Maurice Cherry, Revision Path<br />

is the first podcast to be added<br />

to the permanent collection<br />

of the Smithsonian’s National<br />

Museum of African American<br />

History and Culture.<br />

revisionpath.com/<br />

If you’re looking for more Black<br />

creativity after Revision Path,<br />

try Studio <strong>No</strong>ize, hosted by<br />

artists and printmakers, Jamaal<br />

Barber and Jasmine Williams.<br />

Studio <strong>No</strong>ize features Black art<br />

and artists across mediums<br />

and across the diaspora.<br />

studionoizepodcast.com/<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>'s One Story Up<br />

podcast is a celebration of the<br />

culture of the African Diaspora<br />

and the stories that create<br />

it. Jeanine Hays and Bryan<br />

Mason sit down with creatives,<br />

innovators, and tastemakers to<br />

highlight the intersection and<br />

overlap of these fields while<br />

elevating and expanding our<br />

notion of Black culture, one<br />

story at a time. Listen on your<br />

favorite podcast platform, and<br />

watch on Instagram Live.<br />

84 aphrochic

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans | Hot Topic | Who Are You

ARTISTS & ARTISANS<br />

Dream of Me: The Surreal Self-Portraiture of Fares Micue<br />

There’s nothing more mysterious than a dream — and nothing more meaningful. An<br />

entire world made up of only one mind, a place where anything can happen and all that<br />

does is a reflection of that mind alone. In dreams, the emotions are laid bare, though<br />

they come wearing guises from all the corners of our minds. Like the emotions, dreams<br />

can be bewildering, frightening, and most of all, instructive, though the lessons may be<br />

hard to grasp. To help us better navigate our own inner worlds, fine art photographer<br />

Fares Micune graciously offers us a tour of her own.<br />

In 2009, when Fares first picked up a<br />

camera to try her hand at shooting, it was not<br />

with the intention of beginning an art career,<br />

becoming her own muse, or trying to convey<br />

the varying realities of human emotion. All<br />

of that came later. By her own admission,<br />

all she was after at first were some pretty<br />

photos. But six years later, she realized that<br />

her hobby had become a passion and she<br />

would have to follow where it led.<br />

Originally from Lanzarote, a Spanish-administered<br />

territory in the Canary<br />

Islands, Fares had always wanted to be a<br />

storyteller. In her own dreams, it seemed<br />

that aspiration would lead her to a career<br />

in acting. But in photography she found she<br />

had the same ability to share her stories and<br />

convey her feelings, but in a world that was<br />

hers alone to shape and where hers was the<br />

only voice being heard.<br />

Fares’ style is minimal, but far from<br />

simple. An avowed self-portraitist, her<br />

work eschews busy backgrounds or an<br />

overabundance of elements. Instead, she<br />

works to keep the focus where it belongs,<br />

drawing from her own experiences, reflections,<br />

and an endless creativity to shape an<br />

image around a single, evocative pose —<br />

often highlighted by a single bright shade.<br />

Balloons, flowers, and even paper cranes<br />

play alternating roles, typically obscuring<br />

the artist's face as she lets her body do most<br />

of the work in telling the story. The color of<br />

her brown skin is often a central element in<br />

pieces like, “Believe to See” or “Memories of<br />

a Rainy Day,” where she either stands alone<br />

against a black background or provides the<br />

middle ground between colors. The effect is<br />

ethereal, moving, and above all, beautiful.<br />

Though the emotions she portrays in<br />

her work run the entire spectrum, the artist<br />

maintains a commitment to positivity, both<br />

for herself and in what she hopes others<br />

will see. “I want my images to give hope,”<br />

she shares, “and teach people to appreciate<br />

themselves, to love, dream, and believe that<br />

everything is possible if we believe it is.” By<br />

becoming the conduit of her own emotions<br />

through whimsical poses and fantastic<br />

compositions, Fares Micue hopes to help<br />

us better connect with ourselves. If she<br />

succeeds, then one day changing the world<br />

we have into the one we need could feel as<br />

simple as waking up from a dream. AC<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Previous Page: Believe to See<br />

Right: Cultivate Your Mind<br />

88 aphrochic

ARTISTS & ARTISANS<br />

Focused Energy<br />

Writing a New Chapter<br />

90 aphrochic issue six 91

Left: Wings to Your Dreams<br />

Above: Memories of a Rainy Day<br />

issue six 93

HOT TOPIC<br />

Attention 21st Century: It’s Time to Grow Up<br />

Centuries are like decades. The first few years of one are mostly indistinguishable<br />

from the last few years of the one before. But eventually, new ideas and directions<br />

develop — often by recognizing the limitations of what came before — and slowly, an<br />

identity emerges.<br />

We are now firmly into the second<br />

decade of the 21st century. Despite several<br />