FUSE#5

This edition of FUSE consists of articles contributed by artists who participated in Dance Nucleus' programmes in 2020.

This edition of FUSE consists of articles contributed by artists who participated in Dance Nucleus' programmes in 2020.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

49<br />

27<br />

5<br />

36

4

Foreword<br />

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

da:ns LAB Report Foreword by Shawn Chua<br />

da:ns LAB Keynote Address by Tang Fu Kuen<br />

1<br />

5<br />

9<br />

13<br />

ELEMENT#6 Viral Archives:<br />

Study Notes<br />

by Loo Zihan<br />

ELEMENT#7 Report<br />

by Chan Hsin Yee<br />

Walking by Emma Fishwick<br />

Post-Residency Reflections by Rebecca Wong<br />

@whereismysapo by Ashley Ho<br />

Choreographing Theory — Seven Fragments<br />

On Kitsch by Sheryll Goh and Rachael Cheong<br />

Projections, Paper Dolls, and Effigies by Jereh Leung<br />

Finding Soultari’s Lenggang: Walking Otherwise<br />

by Soultari Amin Farid<br />

The Problematic Danseuse by Nirmala Seshadri<br />

21<br />

27<br />

36<br />

49<br />

57<br />

65<br />

73<br />

79<br />

89<br />

105

Foreword

In our last edition of FUSE, we proposed for 2020 to be a time to<br />

review our modus operandi and move towards alternatives based on<br />

principles of sustainability, simplicity, mutual support and care. How<br />

oddly prescient then, that COVID-19 struck so quickly following that<br />

publication. If we were previously unaware of the precariousness of our<br />

arts ecology and the vulnerability of an arts and cultural worker, there<br />

is no excuse to be now.<br />

With many events scheduled this year cancelled or postponed,<br />

our team quickly shifted focus to redirect some resources as quick<br />

responses to support the arts community. We launched a list of<br />

initiatives that artists could engage in during the collective downtime.<br />

This issue of FUSE features some critical reflections and notes from<br />

our reading group, Jereh Leung and AWKWARD PARTY (Sheryll Goh<br />

and Rachael Cheong) also share their motivations and processes behind<br />

their projects as part of our Micro-Residency programme.<br />

This year’s da:ns LAB became a space for artists to imagine and<br />

propose new ways to consider and enact mutual support and care—<br />

How to Dance When We Are All Ill. Shawn Chua’s introduction of the<br />

LAB and a transcription of the keynote address by Tang Fu Kuen are<br />

featured in this FUSE.<br />

Notwithstanding the pandemic, there are things to celebrate too.<br />

A number of our Associate Members have been able to present work,<br />

some adapting their projects to adopt an online format: Bernice Lee and<br />

Chong Gua Khee’s Tactility Studies: Pandemic Distances, Syimah Sabtu<br />

and Sonia Kwek’s Where You Move Me Most in the Substation’s Septfest,<br />

Amin and Nirmala’s double bill Failing the Dance in this year’s da:ns festival,<br />

and our artists who presented at the festival’s Open Call —Dapheny<br />

Chen, Syimah Sabtu, and Bernice Lee. Hwa Wei-An was in residency at<br />

Rimbun Dahan, while Jereh Leung participated in the CRISOL Italy-Asia<br />

Artistic Exchange and Network Programme that began in October 2020.<br />

As 2020 draws to a close, Singapore is slowly easing restrictions<br />

on social distancing and public gatherings, and artists are gradually<br />

discovering new strategies for their projects and artistic practices. At<br />

Dance Nucleus, we have just submitted our plans for 2021 and beyond<br />

to the NAC. We look forward to rising to the challenges of the coming<br />

few years, and to more tangibly meet the needs of the arts ecology.<br />

Yours Sincerely,<br />

Dance Nucleus<br />

Daniel Kok<br />

On Behalf of the Dance Nucleus Team<br />

2

Hero image for da:ns LAB 2020 Co-Immunity: How to dance when we are all ill.<br />

Photo by TheiKevin

da:ns LAB<br />

2020

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

Produced by Dance Nucleus and presented by the Esplanade, da:ns<br />

LAB is an annual workshop-seminar for artists and arts practitioners to<br />

critically reflect on key issues surrounding their creative practice.<br />

Co-Immunity: How to Dance When We Are All Ill was the 6th<br />

edition of the lab, and took place from 9 –12 July 2020. Co-curated<br />

by Daniel Kok and Shawn Chua, the lab was conducted online with 64<br />

participants across Hong Kong, Manila, New Delhi, Singapore, Sydney,<br />

and Taipei—the most ambitious and heavily attended lab yet.<br />

With virology as a metaphorical framework for the lab, participants<br />

were invited to play the role of cultural “doctors” to reflect<br />

on what has been disordered amidst the global crises and health<br />

emergencies. In this paradigm of illness, we review the precepts often<br />

assumed of the dancing body, as one that is able-bodied, productive<br />

and live. From there, participants explored how dance can operate<br />

within the paradoxical framework of co-immunity; to develop infrastructures<br />

of support and thicker relations of care, building resistance<br />

and resilience across the different arts ecologies in the region.<br />

A full report of the lab by Chan Sze Wei is available on The<br />

Esplanade’s Offstage website.<br />

6

Screenshot of da:ns LAB participants doing head massages.<br />

Provided by Chan Sze Wei

da:ns LAB<br />

Report Foreword<br />

Shawn Chua<br />

This article was written by co-curator Shawn Chua, detailing the overall focus of this<br />

year’s LAB and the contexts that surround it. It was part of an information pack that was<br />

shared with the participants prior to the event.

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

Co-immunity: How To Dance When We Are All Ill<br />

“Now might be a good time to rethink what a revolution can look like.<br />

Perhaps it doesn’t look like a march of angry, abled bodies in the streets.<br />

Perhaps it looks something more like the world standing still because<br />

all the bodies in it are exhausted—because care has to be prioritised<br />

before it’s too late.”<br />

—Johanna Hedva<br />

The world is standing still amidst transnational choreographies of movement<br />

control orders, curfews and lockdowns. Governments implement<br />

stricter measures to enforce social distancing, as an immunological<br />

response to curb the spread of the global pandemic. As events, performances<br />

and festivals are cancelled or deferred to an uncertain future,<br />

many arts and cultural workers are left suspended in its wake. In these<br />

extraordinary circumstances where we are unable to gather, to move,<br />

and even to touch, dancers are faced with an impossible set of conditions—how<br />

to dance when we are all ill?<br />

While COVID-19 is a global health emergency, it also manifested<br />

the symptoms of much longer socio-economic, political and ecological<br />

crises, exposing complex systems that have already been chronically<br />

ill. It painfully revealed the debilitating conditions and vulnerabilities<br />

of being a dancer within a precarious arts ecology. In the region, the<br />

Hong Kong protests are roiled by deep socio-political unrest while the<br />

Australian bushfires warn of larger climate catastrophe. 2020 is in a<br />

state of emergency. But these crises have demonstrated that recovery<br />

in this context should not be a nostalgic return to the normal, because<br />

the existing conditions of the ‘normal’ was what precipitated the crisis.<br />

To dance in such times, we must recuperate the paradigm of illness,<br />

reorienting some of the precepts that are often assumed of the<br />

dancing body, as one that is able-bodied, productive and live. What<br />

choreographies become accessible with the ill-bodied dancer, and can<br />

this embodiment offer different strategies for navigating the crisis?<br />

What remains live when our bodies are screened, and augmented by the<br />

prosthetics of new media technologies? Amidst a contagion—a term<br />

that etymologically denotes “together touching”— can we reimagine the<br />

parameters of dancing together across social distancing, where other<br />

forms of assembly are realised?<br />

The restless ensemble of exhausted bodies is a symptom of the<br />

precarious labour conditions that plague many arts and cultural workers.<br />

It is time for us to take a break from the frenetic rhythms of production,<br />

to slow down, and to deprogramme. By relinquishing our obsession<br />

with the relentless metrics of productive output, we can rehabilitate<br />

10

FUSE #5<br />

our working processes by recalibrating the conditions, protocols and<br />

procedures to more sustainable modes that prioritise our creative practices<br />

and wellbeing.<br />

Inhabiting illness calls for a praxis of care that extends beyond<br />

immunology. Immunological systems are predicated on the exclusion<br />

of a threatening other—a foreign body. Instead of reinscribing the<br />

xenophobic logic of immunitary nationalism, we aim to foster interdependent<br />

networks of solidarity across borders. To reconcile this<br />

immunological metaphor with the contaminations of community, we<br />

will explore how dance can operate within the paradoxical framework<br />

of co-immunity, to develop infrastructures of support and thicker relations<br />

of care, building resistance and resilience across the different arts<br />

ecologies in the region. Through a different kind of embodiment, we<br />

might even feel the possibilities of a movement even as we remain still.<br />

Shawn Chua is a researcher and artist<br />

based in Singapore, where he is engaged<br />

with embodied archives, uncanny personhoods,<br />

and the participatory frameworks<br />

of play. He has presented his research<br />

at the Asian Dramaturg's Network, The<br />

Substation, and Performance Studies international<br />

(PSi), and his works have been<br />

presented under Singapore International<br />

Festival of Arts, Esplanade Presents: The<br />

Studios, Amorph! Performance Art Festival,<br />

and Panoply Performance Laboratory.<br />

Shawn is a recipient of the National Arts<br />

Council Scholarship and he holds an MA<br />

in Performance Studies from Tisch School<br />

of the Arts at New York University. He has<br />

served on the Performance Studies international<br />

(PSi) Future Advisory Board, and<br />

currently teaches at LASALLE College of<br />

the Art. Shawn is also a founding member<br />

of Bras Basah Open School of Theory and<br />

Philosophy and is part of the group that<br />

runs soft/WALL/studs.<br />

11

Photo of Jared Jonathan Luna with mask by Leeroy New.<br />

Photo credit: Bunny Cadag

da:ns LAB<br />

Keynote Address<br />

Tang Fu Kuen<br />

A few weeks before the LAB, participants were sent a recording of keynote speaker Tang<br />

Fu Kuen’s address, which has been transcribed here by Chan Sze Wei. As he reflects on<br />

the LAB’s theme, Fu Kuen offers a perspective that intersects between virology, biology,<br />

and philosophy to consider the ambiguity of medical metaphors and the poor reputation<br />

of viruses. Finally, he shares Jakob von Uexküll’s notion of the “Umwelt”—an indivisible<br />

entity of organism and environment, in which organisms do not occupy their environment<br />

but create it.

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

Hello, everyone. I’m Tang Fu Kuen and I’m speaking to you today from<br />

Taipei. I welcome all of you participants of da:ns lab, “Co-immunity: How<br />

shall we dance when we are all ill.”<br />

What a great title and a very difficult title. I should share that<br />

this has been a big challenge to me. I was thinking, what is the real<br />

function of making this keynote speech? Is it to provoke? And I then<br />

took a back seat and thought about many questions. And of course,<br />

these questions could only develop into even more questions to which I<br />

have no answer. And I begin to think if seeking answers is what we are<br />

tasked to do in this lab. I hope not. Rather, I hope that it is reflection,<br />

sharing and a way of looking back to the past, in order to deal with<br />

what we have now.<br />

The kinds of hardships that we are struggling with right now,<br />

and they are bound to increase in the coming months, I hope not<br />

years or forever, but who knows? So answers is not what I can provide<br />

to you. To be a provocateur is not something I’m very good at. So<br />

neither the cheerleader nor the provocateur. I’m not so sure I could<br />

fulfil those roles.<br />

But rather today, I would like to share with you what I have been<br />

reflecting on. I’ve been reading quite a lot in the past years on political<br />

philosophy and it happens that a number of philosophers have written<br />

from the perspective of immunology and pharmacology. Not just as<br />

biology phenomenon but as socio-political theories on individuation<br />

and community especially in the techno-sphere era. So amongst them,<br />

for example, are Gilbert Simondon, Roberto Esposito, Peter Sloterdijk,<br />

Bernard Stiegler, etc. I’m sure you can find plenty of these online<br />

resources accessible to you, and it all really depends on your own<br />

inclination towards the level of discourse and the kinds of language<br />

you can engage in.<br />

Today, I would rather choose to look at the trope of the contagious<br />

malady which has been used through human history as a metaphor and<br />

motif to represent describe and critique failures of the system by critics<br />

of culture and politics. So the current COVID-19 pandemic is full of<br />

examples that run the entire spectrum from profound to pathetic use<br />

of these metaphors. And the fact that many metaphors are being used<br />

have appropriated or borrowed them from the model and discipline<br />

of evolutionary biology serves to underscore the difficulties that the<br />

metaphoric mode of communication entails, as this has to move from a<br />

figurative language to a scientifically-inscribed logos.<br />

Okay, so now let’s get some facts straight from viruses. They are<br />

basically quite misunderstood. They have been getting quite a lot of<br />

bad press from everyone because we’ve been a bit ignorant perhaps<br />

So basically, when you ask anyone about viruses all you can hear are<br />

14

FUSE #5<br />

complaints. It’s disease this or disease that, infection this, infection that<br />

and no one seems to have anything nice to say about viruses. Can<br />

viruses be positive? So of course, to talk about viruses is easy, and it<br />

would be a shame because we wouldn’t be discussing this right now<br />

without them, right?<br />

So, let’s get back to a bit of real sciences, what real science tells<br />

us. Viruses. Viruses are the most ubiquitous life forms on planet Earth.<br />

They are also the least understood. They live everywhere in nature<br />

everywhere, both on you, and inside of you. Less than 1% are known<br />

to be what they call “pathogenic.” But, many more are known to be<br />

symbiotic or mutualistic or benign. So by “symbiotic” it means they<br />

assist, these viruses assist the host. By “mutualistic” it means both host<br />

and virus benefit from the association. And “benign” means we don’t<br />

know what they do. In addition, viruses’ modus operandi of targeting<br />

specific cell types and interrupting cells’ genetic functioning means that<br />

they can be used to destroy certain cells, certain cell types selectively.<br />

So for example, cancer or HIV. And as well, repair genetic damage in<br />

others. So, next time someone asks you about viruses, you can tell him<br />

or her the scientific facts and show a more proper acknowledgement of<br />

how viruses actually work.<br />

Now, these days, when people say something has gone viral,<br />

“gone viral”, they almost always are using the term as a metaphor for<br />

an event that touches a great number of people and news of which,<br />

is passed from individual to individual especially via social media. As<br />

metaphors go, it’s not so bad.<br />

Of course there’s nothing particularly "virus-like” about microbial<br />

infection. They’re quite different things. So yes, so a number of all these<br />

horrible microbial infection-type diseases spread among individuals via<br />

close proximity or physical contact. But, the term “virus” the etymology<br />

actually comes closer to “vita”, Latin for “life force.” And so, it’s obviously<br />

the better choice for representing any event, idea, or philosophy<br />

that touches masses of people. So “vita”—virus coming from vitality.<br />

More interesting, perhaps, is the somewhat neglected aspect of<br />

viral disease metaphors cultural extrapolation. Now, viruses are not<br />

designed to kill or damage their host. The point of a virus is actually life,<br />

not death. Now, because viruses need living cells to reproduce overtime.<br />

They have developed transmission strategies that make the finding of<br />

living hosts quick and efficient. So ideally, a pathogenic virus will enter<br />

a living system and have sufficient time to make many copies of itself<br />

before it is eliminated by the host’s immunological defences. Now, the<br />

virus survives and then the host survives, that’s the model. The problem<br />

with pathogenic viruses especially those that hosts have not encountered<br />

before is that the system’s effort to find and develop a means of<br />

15

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

Image from the Singapore glossary of What is the COVID Body.<br />

Provided by Chan Sze Wei<br />

neutralising the virus the state of the body is changed. And sometimes<br />

beyond the point at which the body, especially weakened bodies, can<br />

remain alive. Consequently, it is not the virus that kills. It is the body’s<br />

reaction to the virus that kills.<br />

At this point, I would like to go a bit sideways to talk about the<br />

notion of “Umwelt.” So I’m moving a little bit from let’s say, how I’ve<br />

explained the function of virus and how they work, which is a more,<br />

let’s say, empiricist description into what is gradually a more subjective<br />

description. Subjective because now we’re going into the perspective<br />

of the virus.<br />

So, “Umwelt”, it is developed by an Estonian biologist, Jakob<br />

von Uexküll, a bit difficult to pronounce. Uexküll basically introduced<br />

a new school in theoretical biology, which is called ethology. Now, in<br />

contrast to the usual kind of what we call taxonomic approach of<br />

classical theoretical biology, which we know, which consists in studying<br />

living organisms according to their lineage and shared features, Uexküll<br />

believes that one actually cannot know the organism without first observing<br />

how it relates to its environment.<br />

Now, a living organism is first and foremost defined by the specific<br />

relationship it maintains with its environment, rather than by its specific<br />

16

FUSE #5<br />

corporeal features. So instead of departing from a human point of view,<br />

Uexküll tries to look through the eyes of the organisms themselves.<br />

How do they see the world? What part of the world is meaningful to<br />

them? What does this tell us about the organism itself? What counts, is<br />

thus, less what organisms are, but more, where they are and how they<br />

are. That is, how they interact with the environment in which they are<br />

living in.<br />

Now, according to Uexküll, organisms do not merely occupy<br />

an environment, they create it. Their relation to the environment is<br />

not a given but a constant development. Uexküll thus exchanges the<br />

kind of static and passive view of taxonomic biology for one that is<br />

much more dynamic and creative. This development does not occur<br />

solely on account of the animal. It is not the case that the animal<br />

is merely shaping its environment. But that the animal is likewise<br />

shaped by its environment.<br />

Right, so there’s something quite inter-subjective happening here.<br />

Both animal and environment encounter each other in what we can<br />

call a contrapuntal relationship of reciprocal determination. So in the<br />

words of the French phenomenologist, Merleau-Ponty, the animal is<br />

produced by the production of a milieu. A milieu, like the environment.<br />

So the animal is thus a product, an effect of something it has produced<br />

itself. Animal and environment make up an indivisible biological unity:<br />

the “Umwelt” or loosely translated as milieu.<br />

So what Uexküll has clearly offered us is not a mechanistic account<br />

of nature but one that is intentional or expressive. Of course,<br />

this appeal of the living organism towards the world can only happen<br />

if the organism has the right physical features. So for instance, an<br />

animal can only address the world in its liquid form, if it possesses<br />

the physical capacity to extract oxygen from water. But thus, this does<br />

not imply that the physical features of the organisms are the first and<br />

only ground from which to explain “Umwelt.” So we can see that unlike<br />

Darwin, Uexküll does not want to reduce the examination of the unity<br />

of “Umwelt” to examination of the physical correspondences between<br />

living organisms and its environment. So for example, animals with a<br />

thick fur living in a cold environment. So instead, he wants to open it<br />

up to an examination of how the living organism and its environment<br />

relate through their ways of behaving and perceiving. That is to say,<br />

their, let’s say, rhythmic postures, sounds or colours, in short, their<br />

world of sensations and movement.<br />

The COVID-19 virus is special but not for the reason that most people<br />

think. Its infection of our bodies is nothing note-worthy as viruses normally<br />

go. But what COVID-19 has spectacularly achieved is infecting our<br />

machines of culture, economics, and politics, our everyday life on a global<br />

17

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

Photo credit: Raghav Handa<br />

level, leaving none of us untouched. It’s a virus and it’s a meme, and in<br />

order to reduce the inferred levels of mortality in at-risk individuals, our<br />

societies have reacted in unprecedented ways. By mandating the shutdown<br />

of economic and cultural activities, which then right, involves all of us in<br />

the arts field, curtailing the individual by all means of mobility, regulations,<br />

and policies. And increasingly, the legal rights of citizens, entering<br />

thus, into discussions of the bio-politics. And by forcing both individuals<br />

and family groups into physical isolation for an unspecified time interval.<br />

Although, of course, every nation is anxiously opening right now as we<br />

speak, albeit with caution.<br />

So at this point, I don’t know how to really speak, what tenor I<br />

should proceed. And I think I can only speak from a commonsensical,<br />

if not, rather, boring, but nonetheless I hope, sensible way of reading<br />

the situation since I cannot, in any way foretell the future. So, right<br />

now, we’ll have to wait to see if these social reactions will sufficiently<br />

mitigate the damage that the virus will inflict on human population.<br />

In a moral sense, we have no choice but to endure, to endure them in<br />

the hope that they will. But just as a body’s reaction to a pathogenic<br />

virus can leave it in a weakened state, and so susceptible to other<br />

infections that would not prove problematic had the virus not come<br />

along, the economic, social, and cultural reactions that COVID-19 meme<br />

has caused will leave our social bodies in a much weakened state. It will<br />

take a long while, a substantial interval and sustained efforts for our<br />

societies to recover from their reaction to this infection. Or maybe, we<br />

never will. Who knows?<br />

So in thinking about the legacy of COVID-19 especially in the<br />

light of the past experience and knowledge that we’ve accumulated<br />

18

FUSE #5<br />

from other pandemics, such as SARS and Ebola etc., that will likely also<br />

happen again in the future. It will be important to remember that unlike<br />

our bodies immune reactions, we are actually in control of our society’s<br />

reaction to this and future infections. It is in our power to learn from<br />

this infection, and so establish structures that will recognise the danger<br />

and take steps to mitigate harmful social responses, both to future<br />

pandemics and to other events of a holistically environmental nature<br />

as they arrive.<br />

Of course, this process is nothing more or less than an example of<br />

cultural adaptation. As with all forms of adaptation, the key to success is<br />

diversity. But, therein lies also the danger. The strategies that lead to successful<br />

post-event diversification are unknown. Common sensibly, commonsensically<br />

speaking, some lineages will remain more or less unchanged and continue<br />

to pursue their old ways. Others will undergo rapid and profound alteration<br />

to their approaches to life.<br />

Now, success always belongs to whichever strategies work best for<br />

whatever reason. Moreover, adaptations that offer an advantage, whatever<br />

their origin and however slight, can eventually displace those that<br />

don’t. Irrespective of the success the latter may have enjoyed previously.<br />

So prior incumbency does not guarantee success in the aftermath of<br />

a profound dislocation. As it is with nature, so it is with social factors<br />

of economics, politics, and culture, humans, by their given capacity, can<br />

do many things that are highly unusual, even unique. But by definition,<br />

humans can never do anything that’s unnatural. Although, synthetic<br />

biology has been proposing to radicalise that limitation. Hence, my own<br />

personal interest in pursuing and reading up on the future according<br />

to synthetic biology, but this is another matter, another day, we can talk<br />

about this.<br />

Now, due to the manner in which human cultures have responded<br />

to COVID-19 infection, many of our very precious traditions, ways of life,<br />

institutions, have, and to all intentions and purposes been suspended. It<br />

is far too early to tell which will survive after the crisis has passed and<br />

which will remain in whatever state. However, what one can say with<br />

some degree of certainty is this, that aspects of tomorrow’s world may<br />

be very different from yesterday’s world. And we already experience this<br />

now, that the world has changed. So the challenges we’ll face in coping<br />

with that world won’t end with our society’s survival. They’ll only have<br />

just begun.<br />

So on this note, rather, open and you know, how should I say… I<br />

have no conviction about whether we, the world, the human race, will<br />

collapse or continue in what ways, whatsoever I think we will just have<br />

to find ways to keep surviving and then, to keep doing what we need<br />

to do or think in what ways we can best contribute.<br />

19

da:ns LAB 2020<br />

So with this, I wish all of you in Taiwan, in India, the Philippines,<br />

Hong Kong, Singapore, have I missed out any other—Australia! I wish<br />

you all the best in this year’s lab and to take away some of these<br />

reflections I’ve shared with you today into your own discussions. Thank<br />

you, and all the best.<br />

Tang Fu Kuen is Curator of Taipei Arts<br />

Festival (TAF), a city-wide platform held<br />

annually in summer (Aug to Sep) to<br />

present contemporary local and international<br />

productions. With SUPER@#%$?<br />

as theme for its 22nd edition in 2020,<br />

TAF is helmed by Taipei Performing Arts<br />

Center (TPAC) which also runs the Taipei<br />

Children's Festival and Taipei Fringe<br />

Festival. Fu Kuen worked previously in<br />

immaterial patrimoine in UNESCO (Paris)<br />

and in SEAMEO-SPAFA (Bangkok). He was<br />

sole curator of the Singapore pavilion at<br />

53rd Venice Biennale, presenting artist<br />

Ming Wong who was awarded Special<br />

Jury Mention. As independent curator and<br />

producer and dramaturg, he has worked<br />

with multiple platforms across Asia<br />

and Europe.<br />

20

ELEMENT#6<br />

Viral Archives:<br />

Study Notes<br />

Loo Zihan<br />

ELEMENT#6 Viral Archives took place from August to November 2020, and was facilitated<br />

by artist/academic Loo Zihan. As a group, participants spent time considering the<br />

performance of productivity in a pandemic and the building of a collective viral archive.<br />

Here, Loo Zihan shares notes accumulated over the sessions.

ELEMENT#6 Viral Archives: Study Notes<br />

From August to November 2020, I facilitated a small study group of<br />

artists in a workshop titled Viral Archives. We convened six times over<br />

a duration of the three months in-person and online with two main<br />

intentions, the first was to share research methodologies in relation<br />

to artistic practice, and the second to share a space where we could<br />

unpack our experience of the lockdown due to COVID-19 earlier this<br />

year. We started with a group of five participants and concluded with an<br />

intimate session of three. Various participants joined and dropped out<br />

and this was part of the evolving process—there was a sense of fatigue<br />

from the onslaught of arts events internationally and locally that were<br />

made available with remote online experiences, and we were appreciative<br />

what time we could afford together in this study group.<br />

The organizing philosophy of the group was modeled after Fred<br />

Moten and Stefano Harney’s notion of black study that they proposed<br />

in The Undercommons. They call for a kind of fugitive work that refuses<br />

instrumentalisation, coming together in a space outside of the<br />

university to consider ideas, philosophy, practice. When drafting up the<br />

structure, I was also thinking a lot about the study of sociality. I wanted<br />

to interrogate both the subject of ‘social studies’ in the Singaporean<br />

education system and critique the relational turn of socially-engaged<br />

practice in contemporary performance and art. Social studies was<br />

often wielded in our education system as an instrumentalized form of<br />

government propaganda in the 1990s. I wanted to investigate what<br />

would a reconfiguration of social studies with an orientation towards<br />

sociology bring about? Some of the provocations I posed in the first<br />

session included: What does it mean to revisit the study of the social?<br />

Who is counted in this sociality and how do we pay attention to what<br />

is left aside? What is the relationship between the notion of study and<br />

the gesture of practice?<br />

With a desire to break out of habitual modes of engagement, I<br />

invited the group to bond over food and to bring something they consumed<br />

as support through the lockdown period to our first meeting. I<br />

made small jars of achar (pickled vegetables and fruit) for everyone—<br />

something I learnt how to make during the Circuit Breaker period. The<br />

act of assembling achar became a monthly family activity that anchored<br />

us and marked passing time. The sharing of these jars of achar with<br />

my extended family and friends also became a way to demonstrate<br />

affection despite the inability to meet in person. Achar was like a collage—each<br />

batch will be different according to the flavour profiles of<br />

the ingredients added. I have attached the recipe as an appendix to<br />

this document, I would encourage you to try making some yourself.<br />

Others in the group spoke of taking the opportunity during lockdown<br />

to change their dietary habits. A participant brought flourless chocolate<br />

22

FUSE #5<br />

cake that she learnt to make when switching to a keto diet. Another<br />

brought nougats with sesame seeds that she relied on as comfort food<br />

from an Indian mama shop.<br />

Ining, whose family runs a metal workshop in Sembawang,<br />

recounted how Circuit Breaker forced the migrant workers from<br />

Bangladesh and China to bond as they were not permitted to leave<br />

their dormitories and had to share cooking and grocery duties, and<br />

also acclimatise to each others’ dietary preferences. It started a general<br />

conversation about her metal workshop and fabrication which<br />

eventually led to us deciding to visit her studio as part of the final<br />

session in November.<br />

Over the subsequent months, the interest of the group shifted<br />

to research methodologies as we discussed strategies of approach<br />

practice-based research. I was working on an oral history project of<br />

cruising areas in Singapore and shared some difficulties I faced while<br />

conducting these interviews. The second half of the session evolved<br />

into looking at works that negotiate with documenting history, veracity<br />

of accounts, and the ethical positioning of the artist in relation to their<br />

subject. We visited NTU CCA’s penultimate exhibition and discussed<br />

Naeem Mohaiemen Two Meetings and a Funeral video work where<br />

he attempted to reconstruct a history of the Non-Aligned Movement<br />

(NAM) via interviews.<br />

We encountered a mix of theory, audio materials and other<br />

mixed-media as collective points of reference to anchor the conversation<br />

throughout the three months to talk about the promiscuity<br />

of the archive, exposure, and opacity. We read essays penned by<br />

Vijay Prasah regarding the Global Left and the Third World. We<br />

examined S. Rajaratnam’s appearance in the 1973 NAM meeting as<br />

a representative Singapore and the role he performed in shaping<br />

an imaginary Singapore as a global city. We listened to the New<br />

York Times podcast titled Caliphate about the American invasion<br />

of Mosul and reclaiming it from ISIS featuring journalist Rukmini<br />

Callimachi and the peripheral reports that accused her of relying<br />

on unverified sources and challenging the ethical limitations of her<br />

profession. We also took the opportunity to share works-in-progress<br />

to provide necessary critique for each other’s practice, we shared<br />

ways we manage information through online note-taking and time<br />

management apps like Notion.<br />

By way of concluding this short report, I return to a fragment<br />

from a speech in 1979 by S. Rajaratnam that we discovered in the<br />

archives. He titled this speech Old Maps in a New Age and it was made<br />

at the University of Malaya in 1979 on the subject of speaking truth<br />

to power.<br />

23

ELEMENT#6 Viral Archives: Study Notes<br />

"In Apocalyptic times, there can be no set rules to govern our<br />

thoughts. We must therefore take the risk of saying things that are open<br />

to dispute provided that vital problems are thereby raised." Rajaratnam<br />

goes on to reiterate: “It is not that the material for new ideas, the<br />

new maps are not already available. They are all around us in great<br />

abundance. But we cannot see them because of our unwillingness to<br />

empty our heads of old ideas to make way for the new.”<br />

We hope this study group renewed our capacity to find different<br />

methods to read old maps in order to pave the way for new ideas.<br />

Appendix—Vegan Achar Recipe<br />

Makes approximately 1kg of Achar (5 or 6 jars)<br />

There are three main components to making Achar:<br />

1. The frying of the rempah mix<br />

2. The vegetables to be pickled<br />

3. The garnish that is added at the end when everything<br />

is assembled<br />

The rempah (spice paste)<br />

• 3 cloves of garlic<br />

• 3 red shallots<br />

• 1 chunk of blue ginger<br />

• 1 stick of lemongrass<br />

• 2 dried candlenuts<br />

• 2 red chilli padi<br />

• 3 red regular chilli<br />

• ½ teaspoon turmeric powder<br />

Peel the garlic and shallots and chop them into small chunks. Peel and<br />

slice the blue ginger. Remove the center stem of lemongrass and chop<br />

them into very fine bits. Remove the seeds from the chilli and chop them<br />

up (unless you prefer your Achar extra spicy—then leave some seeds in).<br />

Put everything except for the turmeric powder into a food processor and<br />

blend it. Then transfer it to a mortar and pestle and pound the mixture till<br />

it becomes a paste and the flavours are integrated with each other.<br />

Heat 2 tablespoons of vegetable oil on a frying pan, add the paste<br />

when the oil is sizzling, add the turmeric powder at this stage as you fry<br />

the rempah. Fry the paste till it turns slightly golden brown and put it aside<br />

to cool down.<br />

24

FUSE #5<br />

The vegetables to be pickled<br />

• ½ head of cauliflower<br />

• 200g of long beans<br />

• ½ a yellow capsicum<br />

• 1 small turnip<br />

• 1 large carrot<br />

• 3 Japanese cucumbers<br />

• 1 honey pineapple<br />

• 1 red shallot<br />

Chop the long beans, cauliflower, turnip and capsicum into 2cm chunks.<br />

Boil 3 cups of water and blanche these vegetables to cook them till they<br />

are slightly soft before draining them and putting them aside. Chop the<br />

Japanese cucumbers into 2cm long strips. Soak them in salted brine<br />

for about ½ hour before rinsing the brine off them. This is to ensure<br />

they remain slightly crispy when pickled. You may choose to use regular<br />

cucumber instead, but remember to remove the seeds before pickling<br />

if so, Japanese cucumbers tend to be a little bit more crisp. Peel the<br />

carrot and cut them into 3cm long strips. Cut the pineapple into little<br />

chunks—the sweetness of the pineapples really affects the flavour of<br />

the achar, ensure that you are using ripe pineapples and if possible<br />

honey pineapples from Malaysia. Finely chop the shallots.<br />

Assembling and garnishing<br />

• ½ cup of toasted white sesame seeds<br />

• 1 cup of toasted grated peanuts (not powder)<br />

• ½ cup of white rice vinegar<br />

• ½ cup of apple cider vinegar<br />

• 1 tablespoon of gula melaka / brown sugar<br />

• ¾ cup of tamarind assam juice (you can make this by adding<br />

hot water to a golf ball size tamarind paste and sieving it to<br />

filter the seeds out)<br />

Add all the vegetables to a big tub, and stir the rempah paste in while<br />

adding the rest of the ingredients listed above. If you toast your peanuts<br />

and sesame seeds slightly it helps to bring out their flavour before<br />

adding them to the achar. Your gula melaka portion might vary depending<br />

on the sweetness of the pineapples. The apple cider vinegar helps<br />

to reduce the astringency of the achar, but if you prefer your achar tart,<br />

you can add a whole cup of rice vinegar instead. I tend to add these<br />

portions sparingly and taste the mix as I go along to ensure the flavours<br />

are integrated. Do take note that the flavour profile will continue to<br />

mature the longer you leave the achar to marinate. Leave it for an hour<br />

25

ELEMENT#6 Viral Archives: Study Notes<br />

or two chilled before portioning them into the jars to ensure the flavour<br />

is even across the entire batch. After portioning them into jars, the achar<br />

needs time to settle and is usually ready to be consumed the day after.<br />

Do ensure that there is enough pickled brine for each jar of achar.<br />

The achar should be consumed within two weeks, keep checking<br />

the pineapples to ensure the batch is fresh, if they start to turn<br />

brown this is an indication that the batch is about to turn bad. Always<br />

use a clean non-metal spoon to dish out portions to avoid contaminating<br />

the rest of the achar, and having smaller jars ensures easier storage<br />

and portioning. Keep your achar chilled till the point of serving.<br />

Loo Zihan is an artist and academic from<br />

Singapore working at the intersections of<br />

critical theory, performance, and the moving-image.<br />

He received his Masters of Fine<br />

Arts in Studio Practice from the School of<br />

the Art Institute of Chicago and a Masters<br />

in Performance Studies from New York<br />

University’s Tisch School of the Arts. He is<br />

pursuing his PhD in Performance Studies<br />

at the University of California, Berkeley.<br />

His work emphasises the malleability of<br />

memory through various representational<br />

strategies that include performance<br />

re-enactments and essay films. He was<br />

awarded the Young Artist Award (2015)<br />

and an Arts Postgraduate Scholarship<br />

(2017) by the National Arts Council<br />

of Singapore.<br />

26

ELEMENT#7<br />

Report<br />

Chan Hsin Yee

ELEMENT#7 Report<br />

Introduction from Dossier<br />

The Clean Room project has been a major series of work that Juan<br />

Dominguez has created for about 10 years. Structured like a mini TV<br />

series, the work transfers the format of the mini-series into the context<br />

of theatre to propose a different sense of temporality. In Clean Room,<br />

the public is committed to attend each and every one of its episodes,<br />

and is thus led to appreciate the continuity of its proposal, as well as<br />

the production and reception of a theatrical event. Since no new spectators<br />

could be added to the group, participants develop a sense of<br />

complicity and a deep relationship with one another over the duration<br />

of the project.<br />

Following on, the Dirty Room workshop is based on the concept<br />

of seriality derived from the Clean Room project. Using the same<br />

structure and methodology, Dirty Room proposes an experimentation<br />

with time sharing, ways of generating experiences and an idea<br />

of contamination among different agents. The workshop plays with<br />

fragmented temporality and how it might require the renunciation of<br />

traditional narratological elements.<br />

Dirty Room will consist of a chain of situations that activates<br />

individual and collective listening among the participants, raising the<br />

awareness of the here and now, and the idea of complicity. The situations<br />

will prompt reflections on how to be together, where the different<br />

collective gestures performed in the artistic contexts, as well as ‘real’<br />

places and time have the potential to transform individual perceptions.<br />

As we have to make tricky decisions in these situations together, a key<br />

question arises: how the fuck are we going to do all this? (just kidding).<br />

Through this online workshop at Dance Nucleus, we will invent a<br />

lot of things.<br />

28

FUSE #5<br />

Day 1<br />

We began the workshop by doing nothing for 30 minutes together. A<br />

kind of togetherness and non-activity that feels quite familiar during<br />

these times when lockdowns and quarantines are now shared experiences.<br />

We kept ourselves unmuted and visible on screen, catching<br />

soundbites of one another’s worlds, observing the changes in lighting<br />

of Juan’s Spanish morning and our Singaporean late afternoon.<br />

At the end of it, Juan proposed an idea that if everyone gathered<br />

to do nothing together, we could literally stop the world. With his proposal,<br />

the gathering to do nothing took on a political hue as it became<br />

a deliberate choice to resist, to refuse productivity of any kind.<br />

After rounds of introductions, Juan explained the Clean Room<br />

project. This workshop included activities extracted from episodes<br />

of different Clean Room seasons. For this first day of workshop, Juan<br />

facilitated two activities, the first being a bombardment of “questions<br />

that have a twist” from season 1, episode 3.<br />

Some examples:<br />

1. Are you curious?<br />

2. Are you ready?<br />

3. What cinematographic style would you use to film your<br />

life story?<br />

4. Of all the sounds you can hear now, which ones don’t<br />

you recognise?<br />

5. What is the smell of your room?<br />

6. What is the minimum you have to do to make a change?<br />

7. What would you like to be a beginner in?<br />

8. If you were a killer, what kind of killer would you be?<br />

9. Who would you kill?<br />

10. Who else?<br />

11. And what about literature?<br />

12. If you were a sentence, what sentence would you be?<br />

13. Where were you written?<br />

14. Who wrote you?<br />

In the original episode, these questions were broadcasted while participants<br />

were organised in rows snaking around a room, facing one another<br />

in pairs. While we couldn’t go through the entire list of questions, the<br />

list would have gradually invited participants to silently imagine and<br />

speculate about the person—whom they’ve never met—sitting opposite<br />

them. What were they like as a child? Are they a compulsive liar?<br />

What colour underwear are they wearing?<br />

29

ELEMENT#7 Report<br />

It is another kind of being together, and another kind of listening.<br />

No conversation involved, just listening-observing to a person’s body,<br />

their appearance, and to your own imagination’s responses to that body.<br />

The questions would guide you deeper under their skin, as they become<br />

a character you build in your head. You, dear participant, are thus an<br />

important person in each Clean Room episode, because you construct<br />

the actual stories and characters that occur and appear in them.<br />

The second and final activity of the day would have been more<br />

exciting if we had all been physically in the studio together. Juan gave<br />

us a hypothetical amount of $2000 dollars (if only it were real…), and<br />

posed the question “what will you all do with this money together,<br />

that you cannot do alone?” This activity was also from another Clean<br />

Room episode.<br />

We never managed to come to an agreement—time was short.<br />

But the discussion revealed to us where all our headspaces were<br />

during this time—all our proposals centered on sending this money<br />

to vulnerable, less-privileged communities. Like the “questions with<br />

a twist”, our headspace, collective imagination and conversation<br />

build the narrative of this activity/episode within the work. But rather<br />

than speaking about intimate connections growing between discrete<br />

characters, about participants being characters for one another, this<br />

activity’s narrative saw them approaching some semblance of community,<br />

characters interacting with one another, working with one another<br />

towards a real-fictional goal.<br />

Screenshot of ELEMENT#7 participants with Juan Dominguez<br />

in a gathering for nothing. Provided by Chan Hsin Yee<br />

30

FUSE #5<br />

Day 2<br />

While Juan was sleeping, we went off to Funan Mall in the morning to<br />

read a compilation of short stories he had emailed overnight (some<br />

copies are still in the studio, if you are curious). We could not communicate<br />

with one another or acknowledge each other’s presence<br />

under any circumstance—we had to come alone, read alone, and leave<br />

alone, together.<br />

This was the first activity that introduced the idea of complicity to<br />

the narrative of the workshop, in which participants are secondary or<br />

primary accomplices to a secret task or objective unknown by the rest<br />

of the world.<br />

We gathered back online in the afternoon with Juan. This time, we<br />

gathered for nothing for 30 minutes:<br />

“Today 13th of October from 1600h till 1630h We will gather, via<br />

zoom, for nothing. Not for political reasons, not for leisure, not for<br />

socialising. No label, no purpose other than finding out together<br />

what gathering for nothing is. Very different from gathering to do<br />

nothing, what we did yesterday. to do nothing has a purpose. to<br />

gather for nothing doesn't have any purpose.”<br />

We collectively noticed that with no obligation to do nothing, day 2’s<br />

gathering for nothing seemed to pass by faster than day 1’s gathering<br />

to do nothing. There also seemed to be the potential for something<br />

to happen, unplanned and spontaneous, in that gathering for nothing.<br />

Anything could happen when we gather for nothing. With that<br />

playfulness of a gathering for nothing, we also reflected how it was an<br />

activity more familiar to children than adults, which spoke to Juan the<br />

“conceptual clown”, whose practice also includes elements of absurdity<br />

and playfulness.<br />

The last activity for the day was Juan taking us through his process<br />

of creating questions that he used for different Clean Room episodes,<br />

like the ones in the activity we did in Day 1. Perhaps Juan was gradually<br />

inducting us into his band of primary accomplices of this workshop.<br />

The steps:<br />

1. Think of a topic you care about.<br />

2. Write a question about that topic.<br />

3. Add a layer of fiction.<br />

4. Now add a political layer.<br />

31

ELEMENT#7 Report<br />

It was a challenge, needless to say. But through workshopping and formulating<br />

our own questions we found ourselves falling into a rabbithole<br />

of imagination and speculation. It began when we first attempted to apply<br />

that fictional layer to a perfectly ordinary question, and the political layer<br />

took us another step further in. And the descent began when we started<br />

to discuss among ourselves about how we could refine and improve our<br />

provocations. The imaginative, creative process became a collaborative<br />

exercise. It was a co-creation even before it was given into the hands of<br />

a Clean Room participant.<br />

Day 3<br />

Screenshot of ELEMENT#7 participants with Juan Dominguez.<br />

Provided by Chan Hsin Yee<br />

What better way to end the workshop than with the most jam-packed<br />

day of all three days. We began “bright” and early too—the first activity<br />

of the day was to watch the sunrise at Kallang Stadium, in beautiful<br />

evening dress. Again, no communication, no acknowledgements. The<br />

accomplices were to be total strangers to one another.<br />

Again, another opportunity for us to write our own narratives—the<br />

activity could not be enjoyable otherwise. A few of us wrote ourselves<br />

as characters who, after late-night partying, decided they might as well<br />

stay up a little while longer to watch night turn to day. Mysterious men<br />

and women, insomniacs, Breakfast at Tiffany’s wannabes… anything<br />

was possible. The particular context of this activity, with the early<br />

32

FUSE #5<br />

morning darkness and quiet, also made it easier for us to conjure some<br />

dreamy, fictional world. But then seemed to dissolve and blur into a real<br />

world as the sun came up and we saw dogs on their walks, athletes on<br />

their runs, cars on the expressway.<br />

The next activity for the afternoon was the Invisible Gathering. The<br />

accomplices had to gather first at Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple,<br />

then Bras Basah Complex to observe the space and the people in it,<br />

never losing sight of one another as they moved from one location<br />

to another. And, before leaving Bras Basah Complex, the accomplices<br />

had to bend down and tie their shoelaces. All of this to be done alone,<br />

together, without communication and coordination.<br />

The experience of complicity, of sharing a secret that is unknown<br />

to the rest of the world, was particularly intense in this activity. Being in<br />

public spaces, people noticed our presence as a group. Some strangers<br />

paused and joined in the looking around, wondering what we were<br />

waiting for, or lingered in the space anticipating something—we roped<br />

them into our fiction as characters who were “not one of us”.<br />

The accomplices finally managed to meet at their “headquarters”<br />

in the studio for a lunch. There was a table laid out, and food and<br />

questions written on cards were successively placed on it according<br />

to a detailed score provided by Juan to me. I had my own fictional<br />

role to play—the maitre’d, the hostess who disappeared behind the<br />

black curtains and always appeared with more food, more cards. It<br />

was my turn to derive pleasure from being the only one “in on it”, as<br />

the rest of my accomplices were not knowledgeable of my secret with<br />

Juan. Here, storytelling became a shared responsibility or role—each<br />

question prompting memories, experiences, and thoughts. As a group,<br />

we created stories within that story of a lunch. It was a short story, but<br />

rich with laughter and connection.<br />

Back on Zoom, we had these instructions:<br />

“today on 14th Oct at 16h, do not go to the Dance Nucleus studio.<br />

do not be there for half an hour. Our action will happen, inasmuch<br />

as none of us is there. Make sure you know where it is and how<br />

to (not) go. Wear red for this occasion. Stay connected to our<br />

non gathering for the whole time it is not happening. Can you? A<br />

webcam will be streaming our not being there.”<br />

For our final activity, Juan proposed a toast. We all proposed a toast.<br />

Around ten toasts each, actually—60 altogether. This is from another<br />

episode in Clean Room. It is long and drawn-out, a chaotic jumble of sincere<br />

and nonsensical toasts to anything and anyone, real and imagined.<br />

33

ELEMENT#7 Report<br />

We all turned off our cameras and heard one another take turns to read<br />

our toasts. This list of toasts could have gone on forever.<br />

It was a quiet end to the workshop, that was also somewhat poignant<br />

as I recalled how this ELEMENT was meant to be in person, and I<br />

wondered how it might have felt if everyone was in the studio together<br />

with Juan, each of us with a glass in hand. And the ending of our story<br />

would not have been so abrupt as clicking “Leave Meeting”.<br />

So perhaps one more toast: A toast to someday, when we might<br />

do this all over again.<br />

34

FUSE #5<br />

Top: Juan Dominguez. Photo credit: Bea Borgers<br />

Bottom: Hero Image for Clean Room. Photo courtesy of Juan Dominguez<br />

35

Walking<br />

Emma Fishwick<br />

Emma Fishwick (Perth) participated in SCOPE#8 as a regional guest artist, which was<br />

convened by Shawn Chua and Jee Chan. Due to the postponement of ELEMENT#6,<br />

which she had originally been invited to attend, Emma’s week in Singapore was converted<br />

into a residency prior to SCOPE#8. In this essay, Emma uses the movement of<br />

walking to begin speaking about her artistic process and interests, her two projects<br />

that she spent developing and thinking through in the studio, and her reflections on<br />

time alone in the space.

FUSE #5<br />

WALKING<br />

LANDSCAPE<br />

SLOW (art)<br />

Duration Repetition Re-frame<br />

walking<br />

37

Walking<br />

I visited the national gallery the other day and found myself lost in<br />

the space for two and a half hours. The grandeur of the walls, tall<br />

and stark in history, winding up back stair passages and landing in<br />

open spaces, myself alone with the art. There was a work by a Thai<br />

called Two Planets and it sits in the corner of gallery 15. Turning<br />

the corner, I had to consciously walk around to meet it face on,<br />

here I stand shifting my weight from left to right and right to left, a<br />

lingering metronome. A collective of Thai villages sit, staring at an<br />

artificially placed painting, Manet’s “Luncheon on the Grass”. So,<br />

I stand watching people, sitting, watching a painting. Seemingly a<br />

static scene, yet as I linger, a conversation stirs through the villages,<br />

who remark on the female figure, the character’s financial status,<br />

their intentions and so on. They were collectively walking through<br />

this painting together.<br />

Walking we all do it, in some way shape or form, a repeatable action<br />

that overall is a simple process of being and continuing. This process<br />

encourages a cardiac rhythm, a breath, a line of sight, a smell, a memory<br />

or a discovery. Each step, roll or shuffle offers another chance to begin<br />

again or to continue to continue. It is malleable yet easily controlled with<br />

physical, spatial or temporal parameters. These parameters, whether<br />

pre-determined or not, generally define walking as a linear activity.<br />

It has a point A and a point B.<br />

A but not B,<br />

B but not A,<br />

A and B,<br />

Not A and not B.<br />

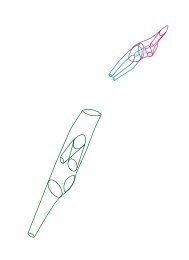

Illustrations by Emma Fishwick<br />

38

FUSE #5<br />

For author Rebecca Solnit, walking is “a bodily labour that produces<br />

nothing but thoughts, experiences, arrivals… the mind, the body and<br />

the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in<br />

conversation together, three notes suddenly making a cord” (Solnit,<br />

2002, p. 5). It offers a form of embodied movement that responds,<br />

connects and shifts ways of thinking, making, seeing and moving and<br />

approaches physical landscapes as “sensory environments… constructed<br />

and understood through kinaesthetic motion” (Rogers, 2012, p. 63).<br />

Doris Humphrey did it as a procession (1928)<br />

Bruce Nauman did it in an Exaggerated Manner (1967)<br />

Richard Long did it backwards (1967)<br />

Trisha Brown did it up and down walls (1971),<br />

Anna Halprin did it in mandalic circles (1987)<br />

James Cunningham does it slow, isolated and performatively (2010–)<br />

Amanda Heng did it so every step counted (2019–2020)<br />

Walking is choreographic, it is rhythm, it offers multiplicity in thinking<br />

processes, it is simple and has the ability to take the body and press it<br />

up against, submerge in and on top of the place in which it finds itself<br />

in. Walking is historical, its durational, repetitious, idle, spatial, temporal,<br />

political and cultural. It is primal, yet not quite universal. For those that<br />

cannot walk, can it still be universal if it is not bound to the body alone?<br />

Can walking be evident without the body? Can process be a long walk?<br />

I visited the national gallery the other day, Sunday 1st March and<br />

found myself wandering throughout the gallery space for two and a<br />

half hours. The grandeur of the walls, tall and stark in history lead<br />

me up winding up back stair passages. So quiet and empty I felt I<br />

was intruding until I’d land in the open spaces, alone with the art.<br />

About one and a half hours in, I came across a video work by a Thai<br />

artist Araya Rasdjarmrearsnook called Two Planets (2008) and it<br />

sits in Gallery 15. Turning left into the gallery I noticed it placed<br />

in the far-right hand corner of the room, I had to consciously walk<br />

around three or four other artworks to meet it face on. Here I stand<br />

shifting my weight from left to right and right to left, a lingering<br />

metronome in front of two TV screens. On one of these screens, is<br />

a collective of Thai villages, who sit, staring at an artificially placed<br />

painting mounted on an easel in a clearing amongst the bamboo.<br />

It was Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1863). It’s the notorious<br />

one, that features two men in their gentlemanly attire, one lady off<br />

39

Walking<br />

in the distance collecting flowers and another in the foreground,<br />

sitting completely naked, staring over her shoulder at us. I could<br />

read that this work runs for fifteen minutes and so, I stand watching<br />

people, sitting, watching a painting, that in many ways was<br />

watching us back. At first this was a seemingly a static scene, yet<br />

as I linger, a conversation stirs through the villages, who remark<br />

on the painting pointing out details and asking questions like; why<br />

is she naked? They must be rich if they are picnicking during the<br />

day? As I watched this work unfold, I realised that these people<br />

were collectively walking through this painting together. Through<br />

their joint sitting, joint idleness, joint wandering of eye and mind,<br />

they were on a collective walk. I too was now part of this walk,<br />

where our could eyes return, our bodies could shift and our minds<br />

question, reframe and discover.<br />

Walking as both an embodied action and as a construct that frames the<br />

way I talk about creative process has been an underlining my artistic<br />

practice for a while now. Increasingly, it has been coming to the forefront<br />

of my residencies, particularly during solo practice. During this<br />

residency, more so than before. During the two-week period, I became<br />

increasingly aware of being alone in the room alone and I noticed my<br />

body becoming both the observer and observed, seer and seen. A<br />

sensation not too dissimilar to the experience of walking, where one’s<br />

“relations with the visible world intertwine in a double movement of<br />

separating and joining” (Wylie, 2007, p. 152). Whether in the studio<br />

moving my body or arranging objects or deciphering text or drawing<br />

40

Emma Fishwick’s presentation at SCOPE#8.<br />

Photo credit: Dapheny Chen

FUSE #5<br />

lines, or out on the street putting foot to pavement, heel to toe, there is<br />

a continual repetitious act of separating and joining.<br />

For this residency, I was in many was walking in the space between<br />

two projects. One concerned with landscape being a relational tool for<br />

re-framing ideas and the other was looking at Slow Art making as means<br />

for re-education of imagery. How do I keep these two projects alive in<br />

the context of solo studio practice? I took the projects’ key concepts,<br />

added the associated objects and materials, mixed them together, and<br />

filtered them through the body. What emerged was the conceptual through<br />

lines between the two projects and the present body. Ideas of duration,<br />

repetition and re-framing to re-educate, arguably all present within the act<br />

of walking. Yet where does this situate the drawn outcomes and arranged<br />

objects within this studio investigation? Where is the walk in that?<br />

The drawing, kept in control through simple parameters of<br />

drawing triangles and going from one end of the scroll the other in<br />

the space of two weeks. The improvised hand that draws or arranges<br />

objects is indeed structured in the same way I would approach improvised<br />

dancing; as an “overlap of associations, distractions, statements,<br />

retractions, repetitions… beginnings, energetic states, regrets, assertions,<br />

full stops, hesitations” (Pollitt, 2017, p. 207), as well as, spaces,<br />

dots, marks, textures and plains. Every response is both a means to<br />

generate knowledge and a means to reflect during action and after<br />

action. The solo studio time inevitably always feels slow, laborious and<br />

at times pointless, yet the time left alone with thoughts, objects and<br />

movements gave way to a cyclic process of reflection. Where, for example,<br />

the object placement is a reflection on the dancing, the drawing a<br />

43

Walking<br />

reflection on the objects and the dancing a reflection—on the drawing.<br />

With the body being the common denominator between art forms and<br />

responses, working as an associative and relational filter for the physical<br />

and imagined happenings that emerge through the studio sessions,<br />

extending “thinking in the tests and moves” (Schön, 1983, p. 280).<br />

In this way process of any kind can be a long walk.<br />

44

FUSE #5<br />

References<br />

1. Brown, T (1971). Walking on the wall.<br />

2. Cunningham, J (2010). Cunningham Walks, sourced from http://cunningham<br />

walks.com/<br />

3. Halprin, A (1987). Planetary Dance<br />

4. Hand, A (2019–2020). Every Step Counts. Singapore Biennale 2019. Esplanade,<br />

Theatres on the Bay, Singapore.<br />

5. Hart, D. (2002), John Olsen. St Leonards, NSW: Craftsman House.<br />

6. Humphrey, D. (1928). Air for the G string.<br />

7. Long, R (1967). A line made by walking.<br />

8. Nauman, B (1967). Walking in an exaggerated manner around the perimeter of<br />

a square.<br />

9. Pollitt, J. (2017). She writes like she dances: Response and radical impermanence<br />

in writing as dancing. Choreographic Practices, 8(2), 199–218. Perth, Australia.<br />

doi:10.1386/chor.8.2.199_1<br />

10. Richman-Abdou, K. (2018), The Significance of Manet’s Large-Scale Masterpiece<br />

‘The Luncheon on The Grass’. Retrieved from https://mymodernmet.com/<br />

edouard-manet-the-luncheon-on-the-grass/<br />

11. Rogers, A. (2012). Geographies of the Performing Arts: Landscapes, Places and<br />

Cities. Geography Compass, 6(2), 60–75. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00471<br />

12. Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action<br />

New York, NY. Basic Books.<br />

13. Solnit, R. (2002). Wanderlust: a history of walking. London, United Kingdom. Verso.<br />

14. Wylie, J. (2007). Landscape. Hoboken, NJ. Routledge.<br />

Emma Fishwick is an Australian (Perth)<br />

artist working across dance, art, design and<br />

scholarship. Creatively, Emma is increasingly<br />

questioning whether dance can achieve<br />

the often-complex connections between<br />

the human and non-human, challenging<br />

her understanding of the form through<br />

incorporating multiple art practices. Emma<br />

is currently lecturing at Western Australian<br />

Academy of Performing Arts, an associate<br />

artist with Co:3 Australia, a STRUT Dance<br />

board member and an active choreographer,<br />

photographer, editor in Perth.<br />

45

Walking<br />

Top, Bottom: Studio installation by Emma Fishwick during her residency.<br />

Photo credit: Emma Fishwick<br />

46

Emma Fishwick’s presentation at SCOPE#8.<br />

Photo credit: Dapheny Chen

Post-Residency<br />

Reflections<br />

Rebecca Wong<br />

Rebecca Wong (Hong Kong) was another regional guest presenters at SCOPE#8. Like<br />

Emma Fishwick, Rebecca spent a week in residency in Singapore before her presentation,<br />

which was spent in reflection and observing female gender and sexuality—Wong’s focus<br />

of artistic interest and study—within the local context of Singapore. She shares some of<br />

her reflections and notes here.

Post-Residency Reflections<br />

<br />

<br />

202032 – 9<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

50

Bird-watching / (2018) by Rebecca Wong.<br />

All photos by William Muirhead

FUSE #5<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

20196<br />

<br />

<br />

Dance Nucleus Residency (2 – 9 Feb 2020) reflections<br />

Residencies offer space for art to develop, and time for the artist<br />

to grow.<br />

Developing art:<br />

My recent performance led to me to view the artist-audience relationship<br />

with suspicion. The performance space conventionally offers<br />

protective boundaries; clear lines that divide the performer and the<br />

audience such that one does not intrude upon the other. The performance<br />

becomes an invisible wrestling of energies, without any real<br />

risk of harm or offence.<br />

My works probe into constraints of Asian women with regards<br />

to gender and sexual desire, and I am primarily motivated by cultures<br />

of patriarchism and female objectification. In my recent performance,<br />

I blurred the boundaries of the performance space, and encountered<br />

audience members from cultures that objectified women who almost<br />

plastered their faces on my naked body. I was able to continue the<br />

performance that day, but the emotions and thoughts of that performance<br />

have continued to stick with me.<br />

When I blur the divisive lines within the performance space, place<br />

the work within the audience, and present my naked body to a group<br />

of people who motivate me to create, do I put myself in danger? As a<br />

creator and performer, how do I sensitively build a relationship with the<br />

audience based on trust and equality? How do I navigate between the<br />

light and darkness of humanity; to embody and affirm shared values, or<br />

perhaps to challenge the audience without losing their trust?<br />

53

Post-Residency Reflections<br />

Bird-watching / (2018) by Rebecca Wong.<br />

All photos by William Muirhead<br />

In most residencies, there is space available for free exploration.<br />

I chose to spend the majority of this residency in that space, walking<br />

around the city, experiencing daily life, whilst reminding myself to fully<br />

explore and immerse into things that pique my interest. I found that<br />

just sitting and having a coffee alone made me curious about how<br />

women in this city lived. I would be taking off my clothes at the hotel,<br />

and realising how this might be breaking the law would change the way<br />

I saw this city. On my evening walks, I would try to strike conversations<br />

with a local, but to no success. It could be my luck, but I think it might<br />

be due to cultural differences? I was not in a rush to find conclusions to<br />

my observations and daydreams, and I found that they became a kind<br />

of nourishment for me, and exercises in which my physical senses and<br />

awareness were sharpened. My past curiosity about myself resulted in<br />

understanding, and so in this unfamiliar space, I was still able to carve<br />

my own path in the residency in much the same way as improvisation.<br />

54

FUSE #5<br />

Growth:<br />

This path allowed me to leave my comfort zones, cut away distractions,<br />

and focus on thinking about my work in new ways as senses that had<br />

been dulled by life were being sharpened again. This is what growth<br />

means to me; the outcomes are not just ends in themselves, but embody<br />

contexts and struggles behind them, and most importantly that they<br />

reflect who I am back to me.<br />

Chance allowed me to get to know a female artist who uses<br />

traditional dance to question the identity and positions of women in<br />

society. When I went to watch a show with her, I noticed a contrast<br />

between her personality interacting with her seniors and friends and<br />

the one reflected in the description of her works I read online. Women<br />

meet their culture’s expectations to varying degrees, yet because the<br />

ethos of the times emphasises the will and opinions of the individual,<br />

they are in a challenging position. Each female artist engages with and<br />

articulates this challenge differently, and this act is considered an act of<br />

courage. With regards to my recent performance, “courage” was a word<br />

I always heard because of my decision to perform naked. But in this<br />

female artist, I saw a different kind of courage which was not a one-off<br />

demonstration in an artistic performance, but manifested in daily acts<br />

of exploration, change, and communication. It is a quiet but steady<br />

strength which is just as hard to come by.<br />

I did not expect a week-long residency in a foreign plane to<br />

bring me so much inspiration. But with Hong Kong in a turbulent and<br />

unstable state since June 2019 to now, being able to leave that space<br />

and breathe a different kind of air released the desire to create that had<br />

been suppressed for so long, allowing it to run freely, unbridled.<br />

Rebecca Wong is a graduate of the Hong<br />

Kong Academy for Performing Arts. Her<br />

choreography and performances question<br />

stereotypes from a female perspective.<br />

At times provocative, her works evoke a<br />