Kobena Mercer – Wifredo Lam’s Cross-Cultural Rhizomes

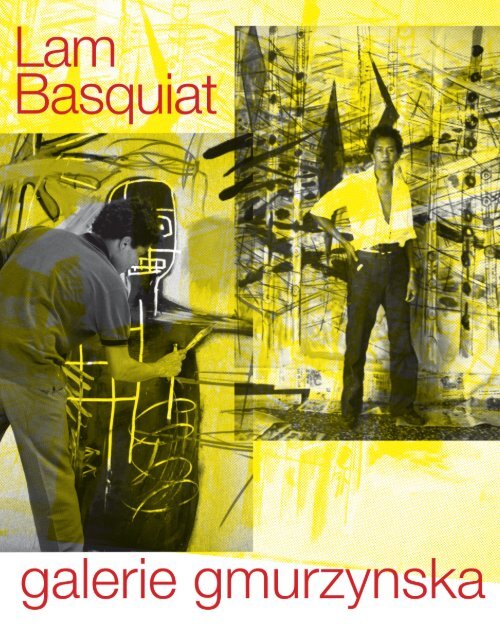

Excerpt from “Lam/Basquiat”, a catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of a special presentation at Art Basel 2015, prepared in collaboration with Annina Nosei.

Excerpt from “Lam/Basquiat”, a catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska on the occasion of a special presentation at Art Basel 2015, prepared in collaboration with Annina Nosei.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Wifredo <strong>Lam’s</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Rhizomes</strong><br />

by <strong>Kobena</strong> <strong>Mercer</strong><br />

is entirely without precedent in twentiethcentury<br />

art. Throughout the period 1941 to<br />

1952, when Wifredo Lam had travelled back<br />

to Havana, we find a poetics of space in which<br />

one’s eye is entranced by enigmatic picture<br />

planes whose intense ambiguity arises from<br />

their simultaneous flatness and openness.<br />

Wifredo Lam<br />

Anamu, 1942<br />

Collection Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago<br />

One feels joyfully disoriented in the<br />

presence of The Jungle, 1943 (collection of The<br />

Museum of Modern Art, New York). As various<br />

anthropomorphic figures push forward from a<br />

dense background of tropical vegetation, the<br />

rhythmic pulsation of the vertical lines that<br />

pull their elongated limbs upward unsettles<br />

any figure/ground distinction to create<br />

instead an “all over” composition in which<br />

one’s eye begins to wander and roam. Before<br />

the identity of the strange hybrid creatures<br />

becomes an issue, one is already swept up<br />

into an all-enveloping pictorial space that<br />

Numerous North American painters<br />

moved towards “all over” pictorial space by<br />

passing through the gateway of abstraction<br />

in the early 1940s, but in the Caribbean<br />

journey that led to his mature style, Lam<br />

activated a cross-cultural dialogue between<br />

modernist painting and the ritual forms of<br />

Afro-Cuban life by reworking the pictorial<br />

resources of figuration completely. In such<br />

works as Anamú, 1942 (collection of the<br />

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago,<br />

Chicago), whose crescent moon face is<br />

rendered in translucent browns and greens,<br />

or the blue and white figuring of Femme, 1942<br />

(Private Collection), where a horse-headed<br />

woman emerges from a shimmering pink<br />

haze, we notice incomplete edges in <strong>Lam’s</strong><br />

delineations of figure and ground. Such gaps<br />

and pauses cut openings and passageways<br />

that allow communicative flow among<br />

different signifying systems otherwise closed<br />

to one another in a colonial world dominated<br />

by an either/or mentality of absolute<br />

separation. To say that, with his return<br />

to Cuba, the border-crossing practice of<br />

hybridity comes to act as the core principle<br />

of <strong>Lam’s</strong> artistic production -- moving<br />

among multiple cultures so as to introduce<br />

58

Wifredo Lam<br />

Autel pour Eleggua, 1944<br />

59

Pierre Mabille and Lydia Cabrera with Wifredo Lam, Cuba ca. 1943<br />

change in place of stasis -- is to say that<br />

the inscriptive space he always keeps open<br />

and flat in his paintings was a key condition<br />

for breaking through into a realm of crosscultural<br />

poetics that carried far-reaching<br />

philosophical implications.<br />

At a time of crisis when Europe was<br />

about to plunge into global war, forcing<br />

Lam to flee Paris in 1940, the humanist<br />

ideals of Enlightenment modernity were<br />

being torn apart. Travelling by ship to the<br />

Antilles in the company of André Breton,<br />

André Masson, and other Surrealist Group<br />

members, it was <strong>Lam’s</strong> friend Pierre Mabille,<br />

an editor of Minotaure and founder of the<br />

Haitian Bureau of Ethnology, who first<br />

recognized what the hybridity principle<br />

was opening up. Decentering the rules<br />

of post-Renaissance picture-making<br />

where monocular perspective created “a<br />

structure dependent on a single centre,”<br />

The Jungle inspired Mabille to argue that,<br />

“this jungle where life explodes on all<br />

sides, free, dangerous, gushing from the<br />

most luxurious vegetation, ready for any<br />

combination, any transmutation,” was<br />

inherently counterposed to, “that other<br />

sinister jungle where a Führer … awaits<br />

the departure … of mechanized cohorts<br />

prepared … for annihilation.” 1 Where<br />

hybridity undercuts all-or-nothing absolutes<br />

by embracing the mutability of boundaries<br />

in the interdependent ecologies of human,<br />

animal, and plant life, <strong>Lam’s</strong> figures --<br />

with payaya-shaped breasts and phallussprouting<br />

chins, with horse-like manes on<br />

mask-shaped heads -- embody a readiness<br />

for further metamorphosis that reveals<br />

something unique about the Caribbean<br />

conditions of their artistic genesis. Lam<br />

flourished when he returned to Cuba, and<br />

while his “homecoming” is often interpreted<br />

biographically, as a reclaiming of ancestral<br />

roots from his Chinese father, Lam Yam, his<br />

mother Ana Serafina, of mixed Iberian and<br />

Congolese heritage, and his godmother,<br />

Mantonica Wilson, a Santeria priestess, I<br />

would say that a broader understanding<br />

of his Afro-Atlantic originality comes into<br />

view when we consider the multiple routes<br />

leading the artist toward hybridity as a<br />

questioning of any claim to fixed or final<br />

identity.<br />

Where New World syncretic religions<br />

such as Santeria combine Yoruba and<br />

Catholic deities to transform European<br />

and African sources in the creation of new,<br />

translational, syntheses, 1940s debates<br />

among artists and ethnographers cast<br />

radical doubt on the idea of assimilation in<br />

colonial governance. Poet Nicholás Guillén<br />

60

and writer Fernando Ortíz coined the term<br />

“Afro-Cuban” to acknowledge the paradox<br />

of the expressive power transmitted by<br />

the lowest segment of their nation’s ethnic<br />

hierarchy. Their investigations suggested<br />

that Caribbean societies were ready for<br />

“any combination, any transmutation” by<br />

virtue of the counter-Enlightenment gained<br />

in coming to terms with violent histories of<br />

forced migration that nonetheless gave rise<br />

to multiple recombinant potentials among<br />

African, Chinese, South Asian, European,<br />

and Muslim diasporas. Ortíz introduced<br />

the concept of “transculturation” in Cuban<br />

Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar (1940),<br />

showing how “the loss or uprooting of a<br />

culture (‘deculturation’) and the creation of<br />

a new culture (‘neoculturation’)” 2 go hand<br />

in hand, thereby mapping altermodernity<br />

avant la lettre.<br />

Addressing the two commodity<br />

crops of Cuba’s agricultural economy as<br />

allegorical personages, Ortíz’s text acts as<br />

a fertile interpretive source for grasping<br />

how subversive <strong>Lam’s</strong> intentions really<br />

were when he said The Jungle, “has nothing<br />

to do with the real countryside of Cuba,<br />

where there is no jungle but woods, hills<br />

and open country, and the background of<br />

the picture is a sugar cane plantation.” 3<br />

Where the title of his 1943 masterwork<br />

appropriates a key trope of primitivist<br />

discourse to resignify la selva (‘the<br />

jungle’) as el monte, a sacred clearing in<br />

the forest (which has correspondences in<br />

European folklore), the cognate term la<br />

meleza (‘the undergrowth’) positions his<br />

creaturely hybrids in a subtle critique of<br />

plantation slavery. In the vertical rhyming<br />

between the sugar cane stalks and their<br />

dancing limbs, we behold a subaltern ritual<br />

performed at night (for the deep blue<br />

background casts the scene in moonlight<br />

even as amber and green foreground tones<br />

evoke illumination by firelight), opening<br />

a line of flight into uncharted realms of<br />

possibility. Since the hybrids are fully<br />

immanent to the undergrowth, in their<br />

transculturative dance they constitute<br />

a rhizome, a term philosophers Gilles<br />

Deleuze and Felix Guattari employ to<br />

distinguish arborescent root systems, such<br />

as oak and pine, which organize growth in<br />

dichotomous hierarchies, from strawberries,<br />

cassava, and mangrove, plants which create<br />

unpredictably interconnective relationships<br />

with their environment, thereby facilitating<br />

the transmutation of identity on the part<br />

of all elements swept up in a rhizomorphic<br />

assemblage. 4<br />

The femme-cheval is another hybrid<br />

figure constantly recurring across <strong>Lam’s</strong><br />

Afro-Cuban production from 1942 onwards.<br />

Addressing the psychic state the Santeria<br />

worshipper enters into when the orisha<br />

is said to cross the border separating<br />

gods and mortals, taking possession of<br />

the devotee by “riding” him or her like a<br />

horse, the femme-cheval visualizes what<br />

happens to human identity in the liminal<br />

state of ecstatic trance, which was a line<br />

of inquiry Zora Neale Hurston pursued<br />

Movie Still from The Living Gods of Haiti, Haiti 1947-51<br />

61

Wifredo Lam<br />

Untitled 1974<br />

in her travelogue, Tell My Horse (1938), and<br />

which avant-garde film-maker Maya Deren<br />

addressed in The Divine Horsemen (filmed<br />

between 1947 and 1951 but completed<br />

in 1977). In border-crossing practices<br />

that allow glimpses of the multiple<br />

identities within reach once the human<br />

is understood as a process of becoming<br />

rather than a fixed or final state of being,<br />

Lam was one of the first twentiethcentury<br />

modernists to grasp the egoloss<br />

in ecstatic experience as a gateway<br />

to fresh possibilities for shared modes<br />

of belonging in a post-Enlightenment<br />

world. Where, in <strong>Lam’s</strong> poetic space of<br />

transculturation, “the pretensions of the<br />

human ego are set aside for a complete<br />

surrender to an all-encompassing force<br />

that is not unlike the Romantic sublime and<br />

certainly signifies the surrender of Lucumi<br />

devotees to the will of the orisha,” 5 the<br />

rhizomes he set into motion as a result<br />

of his multiple journeys, from Cuba to<br />

Spain and Paris and back again, deliver<br />

aesthetic experiences that continue to to<br />

resonate with the global challenges we face<br />

in an era still struggling to come to terms<br />

with the ethics and politics of multiplicity.<br />

62

Endnotes<br />

1. Pierre Mabille, “The Jungle,” Tropiques n 12, 1945, reprinted in Michael Richardson and Kryztof<br />

Filakowski, Refusal of the Shadow: Surrealism and the Caribbean, London and New York:<br />

Verso, 1996, 211 and 212.<br />

2. Fernando Coronil, ‘Introduction to the Duke University Press Edition,’ in Fernando Ortíz, Cuban<br />

Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar [1940 trans. Harrient de Onis], Durham NC: Duke University<br />

Press, 1996, xxvii.<br />

3. Wifredo Lam cited in Max-Pol Fouchet, Wifredo Lam, Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa, S.A.,<br />

1976, reprinted Paris: Editions Cercle d’art, 1989, 198.<br />

4. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “Rhizome,” in Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus<br />

[1980 trans. Brian Massumi] Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 3 - 26.<br />

5. Lowery Stokes Sims, ‘The Postmodern Modernism of Wifredo Lam,’ in <strong>Kobena</strong> <strong>Mercer</strong> ed.<br />

Cosmopolitan Modernisms, London and Cambridge MA: Institute of International Visual Arts<br />

and MIT Press, 2005, 90.<br />

63

Publication © Galerie Gmurzynska 2015<br />

For the works by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Wifredo Lam:<br />

© 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich<br />

Documentary Images of Wifredo Lam SDO Wifredo Lam<br />

Editors:<br />

Krystyna Gmurzynska<br />

Mathias Rastorfer<br />

Mitchell Anderson<br />

Coordination:<br />

Jeannette Weiss, Daniel Horn<br />

Support:<br />

Alessandra Consonni<br />

Cover design:<br />

Louisa Gagliardi<br />

Design by OTRO<br />

James Orlando<br />

Brady Gunnell<br />

Texts:<br />

Jonathan Fineberg<br />

Anthony Haden-Guest<br />

<strong>Kobena</strong> <strong>Mercer</strong><br />

Annina Nosei<br />

PRINTED BY<br />

Grafiche Step, Parma<br />

ISBN<br />

3-905792-28-1<br />

978-3-905792-28-7