AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 5

This issue celebrates the things about Black culture that are enduring, and that can’t be altered by one bad year - our resilience, our creativity and our radical joy. In the pages of this issue we’ll be sharing with you the visionary work that is taking place every day in our Diaspora. We’ll introduce you to a growing community of Black home brewers who are creating their own space in craft brewing. Then we’re off for a photo tour of beautiful Tanzania. We’ll look at the modern work of South African artists Faatimah Mohamed-Luke and Al Luke, and for the holidays, we’ll share with you our modern take on the Pan-Africanist celebration of Kwanzaa. In issue 5 we are thrilled to take you to the hottest decor boutique in Germany, created and designed by our cover star Chris Glass. Then we’ll give you a sneak peek into our latest project - AphroFarmhouse. And our hot topic is an important discussion on the recession and how we can craft an economic plan that puts Black people first. While we are excited to show you all that’s beautiful around the Diaspora, we also want to share with you the reason why we do this work - to educate, uplift and give back. This holiday season we’re excited to let you know about our partnership with (RED) on an exclusive collection of pillows and tabletop to raise awareness and critical funds for the world’s most vulnerable communities impacted by HIV/AIDS and now COVID-19. And you’ll find more amazing products that support Black businesses in our expansive Mood gift guide.

This issue celebrates the things about Black culture that are enduring, and that can’t be altered by one bad year - our resilience, our creativity and our radical joy. In the pages of this issue we’ll be sharing with you the visionary work that is taking place every day in our Diaspora. We’ll introduce you to a growing community of Black home brewers who are creating their own space in craft brewing. Then we’re off for a photo tour of beautiful Tanzania. We’ll look at the modern work of South African artists Faatimah Mohamed-Luke and Al Luke, and for the holidays, we’ll share with you our modern take on the Pan-Africanist celebration of Kwanzaa.

In issue 5 we are thrilled to take you to the hottest decor boutique in Germany, created and designed by our cover star Chris Glass. Then we’ll give you a sneak peek into our latest project - AphroFarmhouse. And our hot topic is an important discussion on the recession and how we can craft an economic plan that puts Black people first.

While we are excited to show you all that’s beautiful around the Diaspora, we also want to share with you the reason why we do this work - to educate, uplift and give back. This holiday season we’re excited to let you know about our partnership with (RED) on an exclusive collection of pillows and tabletop to raise awareness and critical funds for the world’s most vulnerable communities impacted by HIV/AIDS and now COVID-19. And you’ll find more amazing products that support Black businesses in our expansive Mood gift guide.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

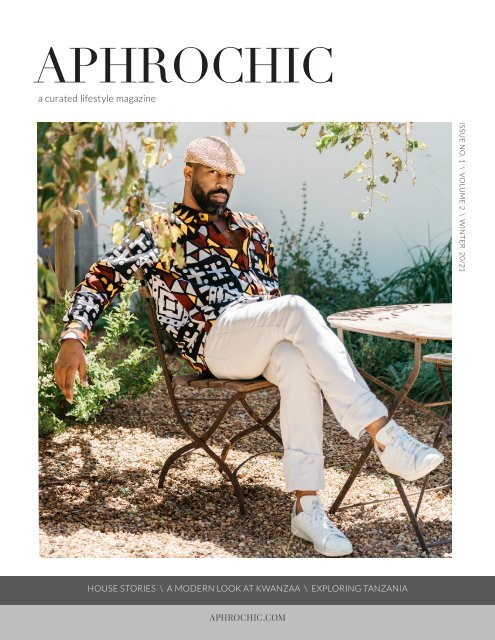

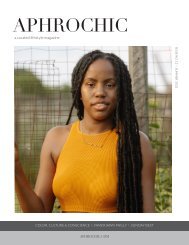

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 1 \ VOLUME 2 \ WINTER 20/21<br />

HOUSE STORIES \ A MODERN LOOK AT KWANZAA \ EXPLORING TANZANIA<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

SLEEP ORGANIC<br />

Avocado organic certified mattresses are handmade in sunny Los Angeles using the finest natural<br />

latex, wool and cotton from our own farms. With trusted organic, non-toxic, ethical and ecological<br />

certifications, our products are as good for the planet as they are for you. Shop online for fast<br />

contact-free delivery. Start your organic mattress trial at AvocadoGreenMattress.com

Ok, we all know it’s true, so let’s say it together one last time: “2020 has been a BEAST.”<br />

But here’s the good news: we’re almost done! This year has been the year of uncertainty.<br />

The world as we know it has changed. And as challenging as it is to imagine how to move<br />

forward, this year has also given each of us a wonderful opportunity - an opportunity to<br />

take stock of who we are, what we’re capable of, and what our purpose is in this world.<br />

This issue celebrates the things about Black culture that are enduring, and that can’t be altered by one bad year - our<br />

resilience, our creativity, and our radical joy. In the pages of this issue, we’ll be sharing with you the visionary work that is<br />

taking place every day in our Diaspora. We’ll introduce you to a growing community of Black homebrewers who are creating<br />

their own space in craft brewing. Then we’re off for a photo tour of beautiful Tanzania. We’ll look at the modern work of<br />

South African artists Faatimah Mohamed-Luke and Al Luke. And for the holidays, we’ll share with you our modern take on<br />

the Pan-Africanist celebration of Kwanzaa.<br />

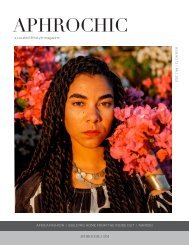

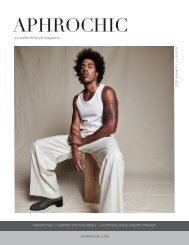

In issue 5 we are thrilled to take you to the hottest decor boutique in Germany, created and designed by our cover star<br />

Chris Glass. Then we’ll give you a sneak peek into our latest project - AphroFarmhouse. And our Hot Topic is an important<br />

discussion on the recession and how we can craft an economic plan that puts Black people first.<br />

While we are excited to show you all that’s beautiful around the Diaspora, we also want to share with you the reason why<br />

we do this work - to educate, uplift and give back. This holiday season we’re excited to let you know about our partnership<br />

with (RED) on an exclusive collection of pillows and tabletop to raise awareness and critical funds for the world’s most vulnerable<br />

communities impacted by HIV/AIDS and now COVID-19. And you’ll find more amazing products that support Black<br />

businesses in our expansive Mood gift guide.<br />

One of the beauties of Black cultures is that we’ve seen hard years before. Hard times don’t break us, they just make us<br />

stronger. 2020 has exposed a lot of flaws and weaknesses in the world as we know it. From pre-existing conditions to police<br />

violence, and lopsided economic policies, many of them are aimed directly at our community. That’s not news to us, but this<br />

year also revealed opportunities for new conversations, new allies and as always, an unshakable commitment to building a<br />

better world.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter

WINTER 20/21<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This 10<br />

Visual Cues 14<br />

It’s a Family Affair 16<br />

Mood 20<br />

FEATURES<br />

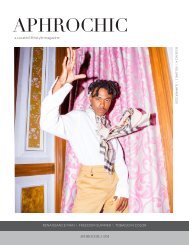

Fashion // Fashioning the Tale 30<br />

Interior Design // House of Stories 38<br />

Culture // A Modern Look at Kwanzaa 56<br />

Food // Homebrewed 66<br />

Travel // Exploring Tanzania 76<br />

Wellness // <strong>AphroChic</strong> Goes (RED) 90<br />

Reference // The Forming of Diaspora 92<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans 100<br />

Hot Topic 106<br />

Who Are You? 110

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

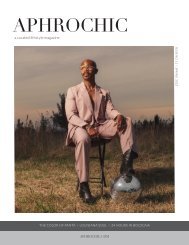

Cover photo: Chris Glass by Kate McLuckie<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Brooklyn, NY<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

info@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors (left to right below):<br />

Lauren Crew<br />

Janelle Jones<br />

Sabina Lee<br />

Camille Simmons<br />

issue five 9

READ THIS<br />

This has been a year to reexamine history, to take a look at what has come before so we can move<br />

forward. The book selections for this issue are all about history, including a look at 75 years of the iconic<br />

magazine Ebony. The magazine broke new ground when it made its debut, and provided a revelatory look<br />

at Black life in America. In How the Word Is Passed, coming out next spring, Clint Smith walks through<br />

iconic landmarks and monuments across the country, revealing the often brutal truth that is hidden in<br />

plain sight. And in The Rise, iconic chef Marcus Samuelsson showcases the cooking of the Diaspora from<br />

its roots to its contemporary recipes.<br />

How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the<br />

History of Slavery Across America<br />

by Clint Smith<br />

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company. $29<br />

Ebony: Covering Black America<br />

by Lavaille Lavette<br />

Publisher: Rizzoli. $57.50<br />

See more book suggestions on page 26.<br />

The Rise: Black Cooks and<br />

the Soul of American Food<br />

by Marcus Samuelsson<br />

Publisher: Little, Brown<br />

and Company. $33<br />

10 aphrochic

READ THIS<br />

ALL HAIL THE QUEEN<br />

The original Queen of Rock, Tina Turner has sold 200 million records worldwide and is a 12-time<br />

Grammy Award-winning artist, including three Grammy Hall of Fame Awards and a Grammy Lifetime<br />

Achievement Award. Tina Turner: That's My Life is the first authorized photo-filled biography by the<br />

legendary artist, showcasing iconic photography, never-before-seen candid photos, letters, and other<br />

personal items. Intended to be the "ultimate scrapbook for her fans," Tina offers insights into the moments<br />

that have made her career and life meaningful to her.<br />

Photo by Jack Robinson<br />

Tina Turner: That’s My Life<br />

by Tina Turner<br />

Rizzoli New York, 2020, $60<br />

Photo by Alberto Venzago<br />

12 aphrochic issue five 13

VISUAL CUES<br />

While museums across the country have struggled with how to survive in a pandemic era with shutdowns<br />

and limits on audiences, the African American Museum in Philadelphia has moved online for its latest<br />

exhibit: Rendering Justice. Curated by artist Jesse Krimes, the exhibit showcases art that examines mass<br />

incarceration while revealing an unflinching view of contemporary America. The art was created as part<br />

of Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Reimagining Reentry program, which works with formerly incarcerated<br />

artists and helps support them in their creation of public art projects. The nine artists worked individually<br />

and in pairs to showcase issues in mass incarceration, with a focus on Philadelphia. The pieces highlight<br />

what it means to be in jail or prison, including the loss of autonomy. And they show how artists can<br />

struggle with their identity both before and after they reenter society. Russell Craig, whose work is<br />

shown below, is a painter and Philadelphia native who survived nearly a decade of incarceration after<br />

growing up in the foster care system. He combines portraiture with strong social and political themes.<br />

To see more of the Rendering Justice exhibit, go to bit.ly/2UjAZCF.<br />

Nipsey triptych<br />

Russell Craig, 2019<br />

Leather, acrylic, bandana<br />

14 aphrochic

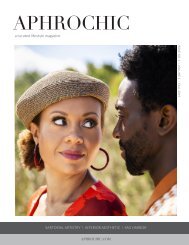

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

A Home of Our Own<br />

As a child, I would sit with my sister and we would sketch out what our dream homes would look like<br />

one day. For me it was always a farmhouse, surrounded by apple trees with a quiet pair of chairs on<br />

the porch for my husband and I to sit and relax as we watched the world go by. As I grew older, those<br />

sketches seemed like just fantasy. First, my husband turned out to be a complete city boy with no interest<br />

in life without skyscrapers and subways. More importantly, I had fallen in love with city life, myself.<br />

Going to school in Atlanta, living in Philadelphia before moving on to Washington DC, San Francisco and<br />

Brooklyn, made it impossible to imagine a return to country life. Especially after Brooklyn.<br />

Late nights at our favorite restaurant,<br />

movies on the weekends, public<br />

concerts in the summer, walking blocks<br />

and blocks just to explore — that’s the life<br />

we’ve always loved. But life is different now<br />

following a major pandemic.<br />

As our world changes in this moment,<br />

my forgotten dream of country living<br />

began to seem less like a fantasy and<br />

more like a better idea — a place that we<br />

own, with lots of space, and where we can<br />

bring our full vision of home to life. When<br />

complications with my immune system<br />

following a bout with COVID-19 made me<br />

sensitive to air quality, it stopped being an<br />

idea and became an urgent next step.<br />

Design runs in my family. I believe<br />

my mom had the design gene. She loved<br />

designing our homes and when she was<br />

done with one house, she was ready to<br />

move. I remember vividly the experience of<br />

going out to search for a new home when I<br />

was heading into the sixth grade. The excitement<br />

of getting to step into an empty<br />

house and see if it was a perfect fit. My<br />

parents eventually settled on a two-story<br />

rancher, but I had fallen in love with a light<br />

blue colonial. At 11, it was my dream house,<br />

not the one I had sketched out, but one I<br />

could imagine myself designing beautifully.<br />

Thirty years later, the dream has<br />

become a reality. What seemed like<br />

something we would never want to do, is<br />

now a new journey that we’re excited to<br />

embrace and very proud to have achieved.<br />

Home ownership is not a given for African<br />

Americans. Starting in 1968 with the<br />

passage of the Fair Housing Act, Black<br />

families began to thrive. For the first time<br />

we found access to homes and neighborhoods<br />

that had historically been closed to<br />

us by a combination of discriminatory laws<br />

and practices and reinforced by the threat<br />

of violence for anyone who succeeded in<br />

breaking through. But racism is a living<br />

thing and, like all living things, it adapts.<br />

Redlining continued despite the<br />

Act, followed by crushing educational<br />

debt, credit reports, predatory lending,<br />

the Great Recession and now COVID-19.<br />

Through it all a series of stereotypical<br />

tropes were woven into the national<br />

psyche, ignoring structural inequalities<br />

It‘s a Family Affair is an ongoing<br />

series focusing on the history of<br />

the Black family home<br />

Photos from Jeanine Hays<br />

and Bryan Mason<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

Jeanine with her sister,<br />

Angela Belt, in the home<br />

they grew up in.<br />

Jeanine at the new AphroFarmhouse<br />

16 aphrochic issue five 17

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

to claim over and over again that it was the<br />

bad choices made by each Black person,<br />

not systematic racism, that was making<br />

it so difficult for us to own homes. So for<br />

decades nothing has been done as home<br />

became a fantasy not just for me but for<br />

most of us.<br />

Today, African Americans in our<br />

generation are less likely to own a home<br />

than our parents or grandparents. As<br />

of 2019, we are the least likely group to<br />

own homes in America, with only 42.1%<br />

of Black Americans owning homes as<br />

opposed to 73.3% of non-Hispanic white<br />

Americans.<br />

Despite the challenges, the girl in me<br />

has never stopped dreaming. This summer<br />

we put on our masks, our face shields and<br />

headed upstate to begin our search. The<br />

first home we saw was not the one. It had<br />

a cracked foundation, broken windows and<br />

a dead bird in it - which we felt was a bad<br />

sign. Fortunately things got better from<br />

there and after a short search we found the<br />

one. It’s a beautiful farmhouse in a small,<br />

sleepy town we had never heard of before,<br />

that feels like it’s the perfect fit for us - our<br />

AphroFarmhouse.<br />

After more than two decades<br />

together, for Bryan and I this feels like a<br />

natural next step. In this new house, we<br />

can truly bring our whole vision to life,<br />

exploring innovative design ideas while<br />

incorporating more of our family story.<br />

Space is not a luxury of Brooklyn living,<br />

but here we finally have room for pieces<br />

like an inherited settee. We’ll finally get<br />

to expand our art collection to feature<br />

our favorite Black artists from around the<br />

world. We might even find space to house<br />

and grow our collection of books. It can all<br />

happen here.<br />

And some may wonder why<br />

ownership matters at all. Buying a home<br />

is not easy and maintaining it is a constant<br />

process. But owning a home is one of the<br />

most basic foundations of our economic<br />

system. It’s an asset. It helps families build<br />

wealth. And without it, it’s hard for Black<br />

families to pass wealth down from generation<br />

to generation.<br />

<strong>No</strong>w, today, we have bought a home -<br />

one that fulfills my girlhood fantasy and<br />

can help our family build. There’s been a<br />

lot to the process and there’ll be a lot more.<br />

But we’re not doing it alone. We’ll be here,<br />

sharing our story with all of you. AC<br />

Jeanine and Bryan<br />

Left: During a college break at<br />

the Mason family home.<br />

Below: During high school at<br />

the Mason family home.<br />

Bottom: Teenage sweethearts at<br />

the prom in 1996.<br />

The AphroFarmhouse<br />

18 aphrochic issue five 19

MOOD<br />

AN ARTISAN HOLIDAY<br />

Dinah by Idris Habib $122<br />

Saatchi Art, bit.ly/2SswiW3<br />

This holiday season we are celebrating artisanship.<br />

Items that are handmade, well-crafted, and beautifully<br />

designed. For the homebody, we have pieces that will add<br />

a special touch to each room of the home. For art-lovers,<br />

we’re highlighting some of our favorite artists from<br />

around the globe. For the lit lovers, we’re celebrating<br />

books by some of our favorite creative minds. And we<br />

have some beautifully handcrafted pieces for the the<br />

fashion savvy, as well. This holiday season it’s all about<br />

the artistry that makes life exceptional.<br />

Day Dream by Natalie Odecor $40<br />

Etsy, bit.ly/3nf8vat<br />

Together by<br />

MKobyArt<br />

$30<br />

Etsy<br />

bit.ly/3jL39BH<br />

FOR<br />

THE ART<br />

LOVER<br />

EXPLORE OUR EXPANDED<br />

GIFT GUIDES ON<br />

PINTEREST!<br />

Mali by Willian Santiago $35.99<br />

Society6, bit.ly/3iukXiN<br />

Twin Celadon by Dawn Beckles $1,305<br />

Saatchi Art, bit.ly/33mIs85<br />

Different Ways To Climb & Unusual Paths<br />

by Isabelle Feliu $35.99<br />

Society6, bit.ly/34oybIZ<br />

20 aphrochic issue five 21

FOR THE<br />

FASHIONISTA<br />

DEMESTIK Bowtie Sculpted Masks $60<br />

Etsy, bit.ly/3d08MZS<br />

A Promised Land<br />

by Barack Obama<br />

$34.99<br />

Target, bit.ly/3ixP35d<br />

The Butterfly Effect<br />

by Marcus J. Moore<br />

$19.57<br />

Walmart, bit.ly/2Guohxk<br />

The Fire Next Time<br />

by James Baldwin/Steve<br />

Schapiro $36.49<br />

Target, bit.ly/36AmZMe<br />

Mateo Diamond Initial<br />

Necklace in Yellow<br />

Gold/White Diamonds $595<br />

Goop, bit.ly/34rLHvp<br />

Who Will You Be?<br />

by Andrea Pippins<br />

$20.99<br />

Walmart, bit.ly/3d10otb<br />

Young, Gifted and Black<br />

by Antwaun Sargent<br />

$47.49<br />

Target, bit.ly/30AxCKT<br />

Kamala Harris by Nikki<br />

Grimes and Laura<br />

Freeman $19.93<br />

Walmart, bit.ly/30A2Z8o<br />

lemlem amira orange plunge-neck dress $495<br />

J.Crew, bit.ly/30zz8<strong>No</strong><br />

BROTHER VELLIES<br />

Ankle boots $330<br />

Yoox, bit.ly/3iAOG9I<br />

Fenty Women's Side<br />

<strong>No</strong>te 54MM Oval<br />

Sunglasses $460<br />

Saks Fifth Avenue,<br />

bit.ly/2Svmwmg<br />

FOR THE<br />

BOOK<br />

LOVER<br />

Off-White Diag Camera Bag $660<br />

LN-CC, bit.ly/33vHwzt<br />

22 aphrochic issue five 23

Harlem Candle Company<br />

Lenox Luxury Candle $45<br />

Amazon, bit.ly/3d2V8Wb<br />

Cravings by Chrissy Teigen 5qt Cast<br />

Iron Dutch Oven with Lid $39.99<br />

Target, bit.ly/33vKnIB<br />

Ankara Apron Set $50<br />

Etsy, bit.ly/2F9IeJq<br />

Jubilation Black Duvet<br />

Cover $540<br />

Perigold, perigold.com<br />

Ayesha Curry Rectangular<br />

Pillow Cover and Insert $50.99<br />

Wayfair, bit.ly/2SuL0vH<br />

FOR THE<br />

HOMIE<br />

Pinto Acacia Round Mirror $199<br />

CB2, bit.ly/3leFCt0<br />

24 aphrochic issue five serenaandlily.com 25

Here is a list of our favorite charitable organizations<br />

that you can donate to this holiday season:<br />

WORLD CENTRAL KITCHEN<br />

wck.org<br />

WCK is working across the country and the globe to distribute<br />

food to communities in need. Founded by Chef Jose Andres,<br />

WCK has provided more than 45 million, healthy, chef-prepared<br />

meals to communities around the world.<br />

UNITED NATIONS FOUNDATION<br />

unfoundation.org<br />

The UN Foundation is working to solve global problems,<br />

including the COVID-19 pandemic. The organization’s<br />

COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund helps with global coordination<br />

of prevention, detection and response to the pandemic.<br />

THE MOVEMENT FOR BLACK LIVES<br />

m4bl.org<br />

M4BL provides legal resources, political actions, and strategies<br />

that support Black humanity and dignity. Their Black Power<br />

Rising 2024 Campaign takes a long-term view of how to<br />

transform Black lives and communities.<br />

(RED)<br />

red.org<br />

(RED) is dedicated to fighting global emergencies, including<br />

HIV/AIDS and COVID-19, emergencies that hit the most<br />

vulnerable populations hardest. This year, <strong>AphroChic</strong> is joining<br />

with the (RED) campaign with (APHROCHIC)RED products<br />

that will be part of the organization’s Shopathon. 10% of the<br />

proceeds from sales of our red products will go directly to<br />

(RED).<br />

26 aphrochic<br />

SHE’S ON<br />

THE FRONTLINE<br />

FOR WOMEN.<br />

We’ve got her back.<br />

red.org<br />

@RED

FEATURES<br />

Fashioning the Tale | House of Stories | A Modern Look at Kwanzaa |<br />

Homebrewed | Exploring Tanzania | <strong>AphroChic</strong> Goes (RED) |<br />

The Forming of Diaspora

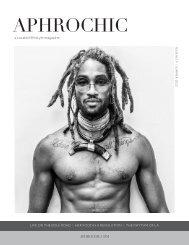

Fashion<br />

Fashioning<br />

the Tale<br />

The Roots and Future of Innovative<br />

Online Dealer The Folklore<br />

Storytelling is at the heart of The Folklore, a<br />

multi-brand e-commerce site and wholesale agency<br />

that delivers high-end contemporary African fashion<br />

and lifestyle products to customers around the<br />

world. According to founder and CEO Amira Rasool,<br />

“Before our real story was told, the only way that<br />

we were able to pass down our history was through<br />

oral folk tale, things going down from generation<br />

to generation. We’re doing the same thing with The<br />

Folklore, but we’re telling stories through clothing."<br />

Words by Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Creative Producer: Raven Irabor | Photographer: Imraan Christian<br />

Stylist: Zizi Ntobongwana | MUA: Justine Alexander<br />

Models: Patricia Laloyo, Samuel Edem, Faith Johnson<br />

30 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

A trip to South Africa with friends<br />

led the former stylist and writer to an<br />

out-of-the-box idea. Clothing that she<br />

brought back from her trip received<br />

such an amazing reaction that Rasool<br />

realized there was an audience for the<br />

brands and products she had fallen in<br />

love with. Armed with an entrepreneurial<br />

spirit and connections in the<br />

fashion community thanks to her time<br />

writing for publications like Vogue,<br />

Teen Vogue, Glamour, and WWD, Rasool<br />

developed the idea to use technology to<br />

bring Africa's most in-demand brands<br />

to global customers. And that’s how The<br />

Folklore began to tell its story of African<br />

fashion, art, and craft.<br />

In addition to products for sale,<br />

there is content on the site, like podcasts<br />

and blog posts written by the designers<br />

and artisans. “We’re giving people from<br />

Africa and the Diaspora the ability to<br />

tell their stories authentically and in the<br />

way they want to,” Rasool says “We don’t<br />

want to dictate what they say and how<br />

they say it, we just want to give them a<br />

platform that complements what their<br />

overall vision in life is.”<br />

Today, there are over a dozen<br />

categories of goods for sale on the site,<br />

including apparel, housewares, and<br />

literature. There are eight countries<br />

represented, with plans to bring on<br />

more companies from <strong>No</strong>rth and East<br />

Africa, as well as the South American<br />

Diaspora.<br />

There are challenges in working<br />

with companies on another continent —<br />

including issues with technology gaps<br />

and payment methods — but Rasool says<br />

the benefits far outweigh any problems.<br />

And, she says, her goal of connecting<br />

African artisans with global customers<br />

is a fulfilling one that has benefited her<br />

in unexpected ways. “We collaborate<br />

to make it a great experience for each<br />

other. It’s been a cultural exchange, and<br />

a great bonding experience. It has made<br />

me feel more connected to have friends<br />

and people I consider family in Africa,”<br />

she says.<br />

Giving voice to those who are<br />

historically ignored is another part of<br />

The Folklore’s story. Including the fact<br />

that the company’s corporate team is<br />

largely comprised of Black women.<br />

“I wouldn’t say it was a conscious<br />

choice, but it was a natural one,” Rasool<br />

says. “The spaces that I’m in are heavily<br />

dominated by women, like the luxury<br />

fashion space. I wanted to be sure that<br />

this time around a luxury company<br />

like this is dominated by Black women.<br />

I think it’s important that Black people<br />

are the ones creating these spaces<br />

for other Black people, and that Black<br />

women — who we’re mostly targeting —<br />

are the main drivers behind what we’re<br />

doing.” AC<br />

Left, Amira Rasool.<br />

Designs featured are by the<br />

brand Sisiano.<br />

Photos were shot in<br />

Cape Town, South Africa.<br />

34 aphrochic

Fashion

House of Stories<br />

A Look at aptm Berlin<br />

by Chris Glass<br />

For Chris Glass, the need to tell stories started early. His ability to do it through<br />

objects arranged in a room was revealed somewhat later. From his earliest days<br />

growing up in Georgia, Chris was a creative person, exploring acting and singing. It<br />

was how people knew him, and how he understood himself. But as he grew, it turned<br />

out that his own story was proving far more interesting than that of anyone he<br />

could play and it was taking him to more places — the well-traveled expat has made<br />

homes in Amsterdam, Turkey, Barcelona and Mumbai to say nothing of countless<br />

other travels to many other destinations. His well-traveled life has introduced him<br />

to more people and showed him more of the world than he could possibly sing about.<br />

<strong>No</strong>w in Berlin, he’s sharing with us his own unique vision of the world.<br />

Photos by Kate McLuckie<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

issue five 39

Interior Design<br />

Every person is the hero of their own<br />

story, but even in your own tale, it can be a<br />

moment before the hero emerges. “I spent a<br />

lot of time behaving well and doing what was<br />

expected of me,” Glass says. “Being the person<br />

that that I was taught to be and sort of staying<br />

within the lines. Because of my theater background,<br />

I grew up thinking everyone should<br />

have one of these classic theatrical stories and<br />

I kept waiting for mine to fall into that script.”<br />

The journey that led Glass away from<br />

characters and to owning an ever-changing<br />

boutique in Berlin is an interesting one. “I lived<br />

in Munich for about eight years, and eventually<br />

moved to Berlin in 2009,” he remembers.<br />

“Munich had become too small for me and I<br />

really needed to be in a place that was more<br />

stimulating and dynamic.” In addition to<br />

owning his own boutique, Glass has the role<br />

of Director for European membership for the<br />

famed Soho House. His role requires that he<br />

connects with the experiences and stories of<br />

others, experiencing new places, people and<br />

cultures.<br />

Much of what he finds becomes part of<br />

building better member experiences for Soho<br />

House’s European clientele. But for his life<br />

outside of his 9-to-5, he’s found a different<br />

outlet as part of a growing relationship with<br />

interior design that has been as unusual as it<br />

has been rewarding.<br />

What sets Glass apart from others in the<br />

design world is that most people who become<br />

designers do so on purpose. Yet for Glass, not<br />

only was it unintentional, it happened largely<br />

without his noticing. Instead of a longstanding<br />

love affair with the profession, for him the<br />

calling came in the form of an actual call made<br />

by someone inquiring about interesting spaces<br />

to shoot for a magazine. His assent, he says, was<br />

nonchalant at best, admitting that he agreed to<br />

have his Berlin apartment shot solely because<br />

he thought it would be fun to show the article<br />

to his mother. As soon as it was done, the shoot<br />

was forgotten about.<br />

As the images circulated, what began as<br />

a single feature quickly became more. “Every<br />

few weeks, she would send me a clipping<br />

and say, ‘Your apartment was featured in this<br />

magazine, it was featured in that magazine.’”<br />

Glass’s bold and eclectic design style, fueled<br />

by finds acquired through his constant travel,<br />

was finding resonance in print and online.<br />

Everyone, it seemed, was recognizing this new<br />

and exciting talent. Everyone, that is, except the<br />

designer himself. “I thought it was somewhat<br />

flattering,” he confesses, “though I really had<br />

no concept of what was going on.”<br />

44 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

The breakthrough moment came when<br />

the attention resulted in an eight-page spread<br />

for a major publication. “I started getting<br />

messages from friends saying 'Your space<br />

is amazing. Your taste is amazing.' And in<br />

that moment, I understood, maybe I've done<br />

something interesting with my space. Maybe<br />

I have a certain point of view or way that I do<br />

things that's interesting to someone beyond<br />

me.”<br />

With the acknowledgement of his own<br />

talent came the question of how best to express<br />

it. It was his first time telling a story that was<br />

completely his own, and naturally Glass felt<br />

protective of it. The point of view he was expressing<br />

in his home was gaining notice, but it<br />

was only one home. And working as a designer<br />

with clients would largely be about expressing<br />

the client’s aesthetic, not his own. He needed<br />

another canvas to paint on, another stage from<br />

which to tell, not just his own story, but all of the<br />

stories he had spent so many years collecting.<br />

The result was a space that is equal parts decor<br />

shop and interactive experience - aptm Berlin.<br />

Opened in 2017, in the Wedding neighborhood<br />

of Berlin’s Mitte district, aptm Berlin<br />

is as much an event space as it is a retail shop.<br />

At nearly 2,500 square feet, this one-of-a-kind<br />

boutique encompasses a large dining, library,<br />

and home office space. “The first response<br />

should be a sense of home, of belonging,” Glass<br />

says of guests visiting for the first time. “aptm<br />

Berlin is an abbreviation for apartment, but it<br />

also is an acronym for ‘a place to meet’. I wanted<br />

to create a space where people and things come<br />

together. A space where people can discover<br />

and be inspired.”<br />

With aptm Berlin, Glass has the best of<br />

both worlds — a place to present his vision<br />

without compromise and with the flexibility<br />

to be changed over and over again, turning one<br />

space into many. And in fact, it is this flexibility<br />

of concept, and the frequency with which<br />

Glass exercises his prerogative for change that<br />

have become the heart of the attraction. “It’s<br />

occasionally seasonal,” he says of the transitions,<br />

“But sometimes also in response to a<br />

recent trip, or a new product that’s been introduced.<br />

And sometimes it’s just because I fancy<br />

changing a wall color and then switching everything<br />

to suit that. This idea is also what<br />

keeps people coming back — the newness and<br />

the desire to discover something unseen.”<br />

From the beginning, Glass envisioned<br />

aptm Berlin as more than a retail shop. With his<br />

rotating designs at center stage, he has used the<br />

interest the space generates as a way to draw<br />

more people in, using this platform to create<br />

and share experiences of their own, while continually<br />

breathing new life into the store’s retail<br />

side. “The space has really morphed more<br />

into a living gallery. People book it for dinners,<br />

photo shoots, filming, meetings. And via these<br />

bookings, people experience the pieces we<br />

have for sale and inquire after to buy things.”<br />

While the space’s first display incarnation,<br />

the aptly titled Birth, conjured images of<br />

something new being brought into the world,<br />

the revision immediately following, called<br />

Dolce, stems from sources far closer to the designer’s<br />

own life and experiences. “I draw inspiration<br />

from so many different places and I<br />

wanted to have the flexibility to show different<br />

ideas,” Glass reveals. “Just before Dolce I’d<br />

begun seeing a therapist who focused on mindfulness.<br />

She really helped me to embrace this<br />

idea of living in the moment.”<br />

Glass extrapolates, drawing the universal<br />

out of the specific to create designed tableaus<br />

that resonate on a number of different levels.<br />

46 aphrochic issue five 47

“This idea is what keeps<br />

people coming back - the<br />

newness and the desire to<br />

discover something unseen.”<br />

“The idea of Dolce is to evoke that moment<br />

when you bite into something sweet. Your<br />

mouth is flooded with sensation and exactly<br />

that moment is what I wanted to capture. It was<br />

also fitting that it is an Italian word as I had an<br />

image of an Italian vineyard during the harvest<br />

and the colors in the space corresponded to<br />

that moment.”<br />

Since then, this design stage has hosted<br />

several other productions including Deutsch<br />

and Umoja, before being slowed down by the<br />

COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly though,<br />

the interruption has been less a setback for<br />

Glass, and more an opportunity to explore<br />

things in a new way.<br />

“We’ve had to slow down and cut back<br />

like anyone else,” he says. “But it’s also allowed<br />

us to literally clean house. Going through and<br />

looking at what is genuinely essential and the<br />

location aspect of our business has become<br />

even more important as people are looking for<br />

quaint, personal, safe spaces for events and<br />

other activities.”<br />

As the saying goes, “all the world’s a<br />

stage,” and in Chris Glass’s world, there’s no<br />

question that it’s true. Through design, this<br />

former singer and actor created the perfect<br />

stage to express his own vision.<br />

Glass’s stage isn’t something he<br />

dominates, but instead a space he shares with<br />

those who visit from all around the world.<br />

Whether it’s for the thrill of seeing something<br />

“unseen,” for the first time or coming together<br />

with a group of likeminded people to explore<br />

new ideas, or just for the fun of spending the<br />

afternoon somewhere out of the ordinary,<br />

Glass offers aptm Berlin as a door to another<br />

world in the the hopes that whatever visitors<br />

bring back will be something they’ll want to<br />

share as well. AC<br />

issue five 49

Interior Design

Interior Design

Interior Design

Culture<br />

Freedom<br />

Summer<br />

An <strong>AphroChic</strong> interview<br />

with Naeem Douglas, the<br />

Brookladelphian<br />

A Modern Look<br />

Interview by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by The Brookladelphian<br />

at Kwanzaa

Since it was first introduced by Maulana Karenga in 1966, Kwanzaa has been<br />

part of the suite of holidays celebrated by Americans at the end of every year.<br />

Yet compared to other winter holidays, Kwanzaa is not especially popular, even<br />

among its target community of African Americans. Though a variety of Kwanzaa<br />

events take place every year, some attracting crowds of thousands, many of us are<br />

unfamiliar with the core principles of the celebration, its history, or its original<br />

intent. For others, the disconnect is aesthetic, rooted in ’60s perspectives on Black<br />

culture and Diaspora and hard to connect with today. But the seven principles<br />

that form the core of the celebration — Umoja (Unity), Kujichagulia (Self-Determination),<br />

Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility), Ujamaa (Familyhood / Cooperative<br />

economics), Nia (Purpose), Kuumba (Creativity) and Imani (Faith) — are<br />

powerful points of focus and we should be careful not to lose them to neglect.<br />

An interview with Christopher Harrison<br />

Conducted by Bryan Mason<br />

Design by <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

issue five 59

Culture<br />

To get a better understanding of the holiday, we sat down with<br />

Christopher Harrison, a PhD candidate in Ethics and Social Theory at<br />

the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, CA, whose studies focus<br />

on Kwanzaa, among other African American social philosophies. We<br />

talked with Harrison about the history and purpose of the celebration<br />

of “first fruits,” and designed our own modern interpretation of this<br />

54-year-old holiday.<br />

AC: It’s widely known that Kwanzaa is a celebration of Black<br />

culture based on seven principles symbolized by seven candles. What<br />

should we know about it? Is there more to the story?<br />

CH: Kwanzaa was never meant to be a once-a-year holiday.<br />

When Karenga first created Kwanzaa in ’66, the Black Power<br />

movement was just beginning to come into focus in California. It had<br />

been a year since Malcolm X had been assassinated and The Us Organization<br />

and the Black Panther Party had just been founded. Karenga<br />

was the co-founder and chairman of The Us Organization and he felt<br />

that in order to be truly transformational, the political efforts of these<br />

organizations needed a cultural foundation. Kwanzaa was intended<br />

to be the basis of that foundation, a kind of cultural revolution to<br />

break Black people out of negative American stereotypes and reconnecting<br />

us, not to a specific African culture, but to a broad cultural<br />

framework based on a variety of traditions from the continent. In<br />

that way Kwanzaa is actually quite ambitious. It’s the beginning of an<br />

attempt to reconstruct a deconstructed people.<br />

AC: All of Kwanzaa’s terminology, including the name itself are<br />

taken from Swahili, an East African language. Some have called this<br />

an anachronism citing the prevalence of West African influence in the<br />

genetics and cultures of the Diaspora. Why was Swahili the language<br />

of choice?<br />

CH: Swahili is one of Africa’s most widely spoken languages,<br />

connecting a number of nations in the central, eastern, and southern<br />

parts of the continent. Moreover it was essentially the lingua franca<br />

of the Pan-Africanist movement at that time. East Africa was in the<br />

process of decolonizing and the leaders of Swahili-speaking nations<br />

like Julius Nuyere and Jomo Kenyatta — the first presidents of<br />

Tanzania and Kenya — were at the vanguard. That gave Swahili the<br />

kind of status that Ghanaian kente cloth had attained under Kwame<br />

Nkrumah. So for the type of practice Kwanzaa was intended to be and<br />

what it was intended to do, Swahili was a natural choice.<br />

AC: Even in the ’60s, Kwanzaa’s popularity was limited by the<br />

idea that it was intended to supplant religious observances like<br />

Christmas. Does that continue to be true today? Can Kwanzaa be<br />

updated or incorporated into other holiday celebrations?<br />

CH: They can certainly be combined now, but that was not the<br />

initial intent. Early literature on the holiday explains it as an attempt<br />

to construct a new philosophical environment for the unlearning of<br />

racists tropes internalized by Black people in America and elsewhere.<br />

Those tropes were strongly present and even reinforced in American<br />

churches with their insistence on the whiteness of Jesus and God.<br />

issue five 61

Culture<br />

Since then however, the lines between<br />

the two have softened. In fact, a large<br />

number of the Kwanzaa celebrations held<br />

every year are given by Black Catholic<br />

churches.<br />

Kwanzaa is not about elevating race<br />

or culture to the level of a religion. History<br />

is full of examples of why that’s a bad idea.<br />

It’s about fostering and reinforcing commitment<br />

to the process of liberation for Black<br />

people around the world — a process, this<br />

year proves, is still ongoing.<br />

AC: Since the 1960s, Diaspora has<br />

replaced Pan-Africanism as the primary lens<br />

for conceptualizing global Black culture. As a<br />

result, many of Kwanzaa’s signature components,<br />

like Swahili or the red, black, and green<br />

color scheme don’t resonate for some in the<br />

same way that they once did. Can the practice<br />

be updated while keeping its significance and<br />

meeting its goals? What are the important<br />

features that need to be maintained?<br />

CH: Without question, Kawaida, is the<br />

most important aspect to be maintained.<br />

Kawaida is the philosophy behind Kwanzaa<br />

as a celebration of the nguzo saba (seven<br />

principles), and can be thought of as the<br />

seven in combination. Maulana Karenga is<br />

still alive so it’s his perspective that really<br />

matters, but in my opinion it’s possible to<br />

alter much of the outer structure of the celebration<br />

and still make it work. But unless<br />

the principles and the goal of Kawaida are<br />

present, it’s not really Kwanzaa. Given that,<br />

it’s possible for the holiday to be celebrated<br />

in different ways in every culture and<br />

household while keeping to the observance<br />

of the nguzo saba. That flexibility would<br />

be more in accordance with how we see<br />

Diaspora today, rather than Pan-Africanism<br />

in which the uniformity of the practice was<br />

part of the point. It also gives us the ability<br />

to update the practice while passing on the<br />

principles.<br />

AC: What books or resources would<br />

you recommend for anyone wanting to learn<br />

more about Kwanzaa?<br />

CH: I would suggest starting with his<br />

website, maulanakarenga.org. Also Molefi<br />

Asante wrote an excellent biography called,<br />

Maulana Karenga: An Intellectual Portrait.<br />

64 aphrochic issue five 65

Food<br />

Homebrewed<br />

A Black Beer Lover’s<br />

Journey into the World<br />

of Craft Beer<br />

“There is an art,” my brother Charles says,<br />

“to learning to make the thing you drink and<br />

enjoy it.” As one of a growing number of Black<br />

homebrewers, it’s a saying and an art that my<br />

husband Joe has deeply embraced.<br />

Words and photos by Camille Simmons<br />

66 aphrochic

Food<br />

Charles is always saying things like that. He’s quirky, and with<br />

a lot of interests outside of the usual stereotypes for Black men,<br />

he’s played a big role in Joe’s developing love for beer and his skill<br />

at creating his own. The two started brewing together in 2010. It<br />

didn’t take long for Joe to know that he was hooked. As a mechanical<br />

engineer, the detail-oriented process appealed to him, but also<br />

offered a level of creativity far beyond what he was used to. That year<br />

they brewed a strong Belgian tripel, and with my brother cheering him<br />

on to start his own creations, I bought Joe his first one-gallon brewing<br />

kit. Joe began learning simple recipes like a grapefruit honey ale, an<br />

IPA, and an oatmeal stout. Our friends and family became his taste<br />

testers and he loved their reactions as much as they loved his work.<br />

But part of what made these words of encouragement so valuable at<br />

the time is that they were also rare in a field that, even now, has few<br />

participants of color.<br />

Representation in homebrewing is much like it is in a number of<br />

other activities. Black people drink beer, of course, just like we drink<br />

wine. But when it comes to the art and, more importantly, the business<br />

of making it, that’s a different game. Our presence at the table is often<br />

not welcome, and it’s never expected. As strange as that ever is, it’s especially<br />

odd in the case of beer which, as the world’s oldest surviving<br />

recipe, was first recorded in 5000 BC — by Egyptians.<br />

Three years after we began our homebrewing journey, Joe<br />

and I were visiting wineries in Sonoma, CA, with my mother for her<br />

birthday. We visited a local community that is very popular with beer<br />

lovers and brewers alike. Joe was excited about the visit, and eager<br />

to chat with the bartenders about their craft process. Instead, we<br />

were greeted with unsubtle glares from a room seriously devoid of<br />

diversity. Joe struggled even to place an order as he was peppered with<br />

questions like, “Do you know what we have here?” and “Do you know<br />

it’s just beer?” Sadly we’re used to these interactions so Joe brushed<br />

off the condescending tone and proceeded to order. We salvaged the<br />

night, enjoyed the beers, even got a few to take home.<br />

Fortunately, though representation remains an issue and the<br />

condescension of those unused to Black faces in what they think<br />

of as “their” spaces continues to be a reality, the Black homebrew<br />

community is a growing contingent and their accomplishments are<br />

real. In 2013, Annie Johnson became the first African American to ever<br />

be named Homebrewer of the Year by the American Homebrewers Association,<br />

only a year after she won the Master Homebrewer Competition<br />

held by Pilsner Urquell in San Francisco. And in 2018, Day Bracey<br />

and Mike Potter, the founders of Black Brew Culture, hosted Fresh<br />

Fest, the first festival dedicated to craft beer lovers of color and the<br />

celebration of Black-owned breweries.<br />

For us, homebrewing has been part of our journey for the last<br />

10 years. Every step we took for one led to more developments in the<br />

other. We were living in Oakland at the time when Joe found a homebrewers<br />

supply shop in Berkeley that encouraged him to keep exper-<br />

68 aphrochic issue five 69

Food<br />

70 aphrochic issue five 71

Food<br />

imenting with recipes, trying out different<br />

beer styles, hops (the plant that gives beer its<br />

recognizable taste), and other flavorful ingredients.<br />

As he learned the basic styles like<br />

pale ale, porter, stout, and pilsner he would<br />

brew a batch about once a month in our tiny<br />

apartment. Before long, he had fans and<br />

realized he needed a larger brew kit.<br />

When we decided to move back<br />

home to Long Beach, CA, we found a great<br />

apartment by the beach, with a garage<br />

space that could house Joe’s growing laboratory.<br />

He still brewed on a monthly basis,<br />

but also made special batches for friends’<br />

weddings, birthdays, and baby showers. I<br />

opened a decor and flower boutique and Joe<br />

brewed special floral varieties (like a honey<br />

lavender saison) for my customers to enjoy at<br />

tasting parties in the shop. As word of mouth<br />

spread, he applied to Airbnb to host a homebrewing<br />

experience in our apartment. Soon,<br />

we had strangers from all over the world<br />

spending Saturdays in our home, falling in<br />

love with the process of making beer.<br />

Keeping up our visits to breweries<br />

and beer festivals has only helped our circle<br />

grow. The festivals are lively events, filled<br />

with crowds that deeply appreciate quality<br />

craft beer. And we’ve even seen a few more<br />

breweries popping up led by women and<br />

people of color. In 2017, at the LA Beer Week,<br />

Joe met an exuberant beer fan, Teo Hunter,<br />

with a mission to show that Black people are<br />

an important and vibrant part of the craft<br />

community. With his business partner Beny<br />

Ashburn, Hunter formed Crowns & Hops, a<br />

Black-owned brewery focused on dramatically<br />

shifting the culture of craft beer. While<br />

still managing his full-time job as a technology<br />

consultant, Joe acts as their right hand,<br />

helping the duo to navigate the worlds of<br />

data analytics and brewery operations. Since<br />

beginning, Crowns & Hops has begun partnering<br />

with established breweries to release<br />

limited edition batches, both in California<br />

and internationally in the UK and Germany.<br />

In the long term, Joe plans to follow his<br />

passion and transition to the beer industry<br />

full time.<br />

Black breweries are still just a tiny<br />

minority. Of the 6,300 small, independent<br />

breweries in America, only 50 are Blackowned.<br />

But from brewing with my brother<br />

over a hot stove in the summer humidity of<br />

<strong>No</strong>rthern California 10 years ago to helping<br />

a fledgling company take international steps,<br />

Joe’s passion for what he does has brought<br />

us deeper into a community that loves the<br />

art of beer just as much as he does. That<br />

community is making strides to make its<br />

voice heard and its presence felt not just as<br />

a customer base, but as enthusiasts, artisans<br />

and entrepreneurs in their own right. AC<br />

72 aphrochic issue five 73

Food

Travel<br />

Exploring Tanzania

Travel<br />

Like so many places on the African continent, Tanzania is ancient and<br />

beautiful. The modern state, born of the fusion of the sovereign state of Tanganyika<br />

and the island nation of Zanzibar, is home to Mount Kilimanjaro,<br />

as well as vast plains and coral reefs. With a history that stretches back for<br />

millennia, this East African nation has traded with empires, survived colonizations<br />

and breathed life into Diaspora. Photographer Lauren Crew takes<br />

us on a visual journey of this incredible country, from rural towns to its<br />

prized tourist destinations.<br />

Photos by Lauren Crew<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

78 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

Referred to by academics as the The Cradle of Mankind for<br />

the age of the tools, remains, and settlements discovered within its<br />

borders, Tanzania is also considered the birthplace of the Swahili<br />

language and culture. The nation is home to the Hadza people, one<br />

of the world’s oldest surviving isolated ethnicities, who continue a<br />

language tradition and culture that appear to have remained largely<br />

unchanged since ancient times. At the same time, the various nations<br />

that preceded modern Tanzania appear prominently throughout<br />

history.<br />

Collectively called Azania by the Greek historian Ptolemy in the<br />

2nd century AD, the Swahili Coast, which included Tanzania, was<br />

known as a hub of trade. By the second millennia, the Swahili Coast<br />

was a vital part of the thriving Indian Ocean Trade. This network of<br />

trade routes connected more people than the Silk Road, reaching well<br />

into Asia as well as the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Europe. One<br />

town in particular, Kilwa, located on what is now Tanzania’s southern<br />

coast, was singled out as one of the best cities in the world by the 14th<br />

century Islamic historian Ibn Battuta.<br />

By the 1960s, the newly formed nation of Tanzania had survived<br />

the decline of the Indian Ocean Trade and more. After occupation by<br />

the Portuguese and later the Omani in the 16th century, it fell under<br />

German control in the 19th century and British control in the 20th,<br />

being dragged into two World Wars in the meantime. But in 1964,<br />

Tanzania declared independence from British colonial rule. Ten years<br />

later, after sharing its language with the international community of<br />

Pan-Africanism, the nation’s first president Julius Nyerere convened<br />

the 6th Pan African Congress, which introduced the world to the idea<br />

of the African Diaspora.<br />

Its fascinating history and natural splendor make Tanzania home<br />

to some of the world’s most entrancing destinations. Four hundred<br />

miles from the slopes of Africa’s highest mountain — Kilimanjaro —<br />

Zanzibar City recalls the nation’s history of travel and trade. There,<br />

old trade fortresses stand beside a sultan’s palace and 19th century<br />

Persian bathhouses fed by a series of antique aqueducts. In the north,<br />

the Ngorongoro Conservation Area boasts Serengeti National Park<br />

with its hornbills, hyenas, and lions amid a vast array of wildlife.<br />

Lauren Crew’s photography also takes us west into the<br />

Nyarugusu refugee camp, one of the largest refugee camps of the 21st<br />

century. The red clay camp, which was first created in 1996, has been<br />

a refuge for those escaping the war in Congo, and now the conflict in<br />

Burundi. It is now home to over 65,000 Burundians.<br />

Tanzania is one nation with many stories. Traveling through the<br />

country you can’t help but be taken by the sheer variety of its landscapes,<br />

the richness of its history, and the beauty of its people. AC<br />

To aid refugees at the Nyarugusu refugee camp, donate to Oxfam: secure2.<br />

oxfamamerica.org/page/contribute/donate.<br />

82 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

issue five 89

Wellness<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Goes (RED)<br />

Introducing CULTU(RED)<br />

During this year’s season of giving, we are thrilled to announce<br />

that we are giving back. <strong>AphroChic</strong> is partnering with (RED), and participating<br />

in (SHOPATHON)RED with an exclusive new collection<br />

entitled CULTU(RED).<br />

In 2006, (RED) was founded by Bono and<br />

Bobby Shriver to engage businesses and people<br />

in one of the greatest health emergencies, the<br />

AIDS pandemic. To date, (RED) has generated<br />

$650 million for the Global Fund to support HIV/<br />

AIDS grants primarily in eSwatini, Ghana, Kenya,<br />

Lesotho, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, and<br />

Zambia. Today, as COVID-19 threatens to undo<br />

the progress of the AIDS fight, (RED) is supporting<br />

the fight against two deadly pandemics,<br />

AIDS and COVID-19. To date, COVID-19 infection<br />

rates in Africa have not been as severe as in other<br />

parts of the world, yet the pandemic’s impact on<br />

critical health services has been devastating. The impact of COVID-19<br />

could cause AIDS-related deaths to double in the coming year as health<br />

and community systems are overwhelmed, treatment and prevention<br />

programs are disrupted, and resources are diverted among the most<br />

vulnerable communities, including those in sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

Having lost family members to this crisis, as well as being<br />

impacted by it personally, we are excited to do our part in helping the<br />

world take back control from this virus. Part of that means helping to<br />

raise awareness around contributing factors such as preexisting conditions<br />

and equal access to healthcare, both on the African continent<br />

and throughout the Diaspora as well.<br />

Our CULTU(RED) collection will feature<br />

a number of <strong>AphroChic</strong> patterns including our<br />

signature Silhouette and Sisters designs, turned<br />

red as a show of solidarity with the campaign and<br />

its many partners. The collection will include<br />

our pillows as well as exclusive items such as<br />

table runners, placemats and dinner napkins.<br />

We will also be offering a limited run of exclusive<br />

CULTU(RED) T-shirts.<br />

Times like this teach us a lot. More than<br />

anything they teach us that the more we all do<br />

for each other, the easier we can make things for<br />

everyone. This year, maybe more than any other we’ve experienced,<br />

we all need to feel like we can do something to make things easier.<br />

For us, that’s always meant making beautiful things that have a story,<br />

make a difference, and give back. AC<br />

Shop the <strong>AphroChic</strong> CULTU(RED) collection as part of (SHOPATHON)<br />

RED on Amazon.com/RED.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason

Reference<br />

The Forming<br />

of Diaspora, Part 1<br />

A New Lens<br />

for a New World<br />

In 1965, after more than six decades of Pan-Africanism,<br />

a new paradigm was emerging, led by a new generation<br />

of intellectuals, politicos, and activists. In that moment,<br />

the framework that had begun with a brief conference in<br />

London, had been formed in the shadow of empires, grew<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Pascal Genest<br />

to span nations and, nurtured by many of the best minds of<br />

the century, played a key role in reshaping the world, began<br />

to end.<br />

Yet the introduction of the African<br />

Diaspora concept by Joseph Harris and George<br />

Shepperson in 1965 was more than a rhetorical<br />

passing of the guard. It signified deep changes<br />

in the ways that Black people all over the world<br />

were seeing themselves in relationship to their<br />

homelands, to Africa as both continent and<br />

symbol, and to each other. Bringing all of that<br />

into focus would take more than one word.<br />

Much more. But before the African Diaspora<br />

could become real in the minds of those who<br />

would comprise it, it would first have to be<br />

formed and defined in ways that would meet the<br />

new needs of a changing time. Chief among the<br />

questions to be answered between Pan-Africanism<br />

and Diaspora was, what’s the difference?<br />

Among the many aspects that differentiate<br />

the two frameworks, perhaps the most<br />

significant is the basic way in which each conceptualizes<br />

the relationship between the individual<br />

Black person of any nationality, the<br />

continent of Africa, and the whole community<br />

of Black people worldwide. Any number of<br />

other differences exist, especially as Diaspora<br />

continues to work to define itself more fully.<br />

But this is most important, because it is on the<br />

foundation of these points that both philosophies<br />

build the entirety of their perspectives.<br />

Form and Function<br />

For Pan-Africanism, the basic foundation<br />

of its outlook is expressed in an idea that<br />

could loosely be described as “the underlying<br />

African self.” This idea posits that beneath<br />

the cultural specificities of any nationality<br />

or ethnicity, there exists an underlying,<br />

original or essential part of every Black person<br />

that connects us to the African continent and<br />

therefore to each other.<br />

Though the idea of an essential African-ness<br />

connecting all Black people might<br />

continue to resonate to a greater or lesser<br />

degree today, at the time it was all but common<br />

knowledge. During Pan-Africanism’s tenure<br />

there was no “African-American” as Jesse<br />

Jackson would popularize the term in the<br />

1980s, only the African (or more commonly,<br />

the Negro) in America. Black people in other<br />

parts of the world were thought of similarly,<br />

not as belonging to the place, regardless of<br />

where they were born, but as being the Negro<br />

here or there. The idea is even borne out in<br />

the title of Shepperson’s introductory article<br />

on Diaspora with its use of the phrase, “The<br />

92 aphrochic issue five 93

Reference<br />

African Abroad.”<br />

By necessity, “Africa” played a central<br />

role in this conceptualization, which arguably<br />

saw what we now think of as distinct Diaspora<br />

cultures as different aspects or at least various<br />

iterations of a comparatively monolithic<br />

African culture. And while it is problematic<br />

for us today to reduce Africa to a monolith,<br />

ignoring the plethora of cultures that make<br />

up the world’s second largest continent, at<br />

the height of colonialism the only difference<br />

between African nations considered meaningful<br />

was the flag of the European nation that<br />

occupied them.<br />

Whatever anachronisms we might accuse<br />

the idea of today, it’s clear that in its time,<br />

the underlying African self was not simply<br />

a romantic notion, but a philosophical and<br />

political tool. It was a refuge for every Black<br />

person either disowned by the place of their<br />

birth or oppressed in it by the absent monarch<br />

of a distant empire. It was the basic building<br />

block that made cooperation and joint struggle<br />

across oceans possible, allowing the first<br />

Pan-African Conference in London to become<br />

Pan-African Congresses around the world,<br />

and Harlem’s New Negro Movement to become<br />

Negritude in Martinique, Senegal, Paris, and<br />

more. The composite symbol of Africa that<br />

it employed, even if not understood in the<br />

moment as being distinct from the actual<br />

continent, met the needs of dispersed people,<br />

themselves a cultural and genetic composite<br />

of many African nations, while drawing their<br />

attention and efforts to the aid of a spiritual,<br />

if not physical, homeland as deeply in need of<br />

them as they were of it.<br />

Unity or Difference<br />

As the successful application of the<br />

Pan-African framework led to the accomplishment<br />

— at least in part — of the purposes<br />

for which it had been conceived, the state of<br />

affairs within the global Black community<br />

began to shift so that the framework itself no<br />

longer applied. The introduction of the term<br />

‘diaspora’ by Harris and Shepperson was the<br />

beginning of a necessary new direction in the<br />

study of Black cultures and communities, one<br />

that centered on a change in focus from unity<br />

to difference as the defining element of relationships<br />

between Black cultures internationally.<br />

As scholar, Brent Hayes Edwards puts it,<br />

“[diaspora] focuses especially on relations of<br />

difference and disjuncture in the varied interactions<br />

of black internationalist discourses,<br />

both in ideological terms and in terms of<br />

language difference itself.”<br />

In the years that followed its introduction,<br />

the formation of the African Diaspora<br />

as a field of study would be significantly<br />

aided in the task of theorizing difference<br />

by the work of British Cultural Studies, itself<br />

an emerging field at that time. In particular,<br />

Stuart Hall’s theory of Articulation, a derivative<br />

of the Marxist thought of Louis Althusser,<br />

would give the African Diaspora the vocabulary<br />

with which to address issues of difference.<br />

These distinctions had become increasingly<br />

prevalent as the Pan-Africanist call for ‘African<br />

Unity’ subsided in the face of growing political<br />

independence.<br />

Prior to the emergence of the African<br />

Diaspora concept, the desire for unity that<br />

animated both cultural and political Pan-African<br />

movements served to limit not only<br />

the study of the various cultural and political<br />

elements of the Diaspora, but the confines<br />

of Black identity as constructed around the<br />

shared image of Africa as homeland. As Hall<br />

himself put it:<br />

[S]uch images offer a way of imposing<br />

an imaginary coherence on the experience of<br />

dispersal and fragmentation, which is the history<br />

of all forced diasporas. They do this by representing<br />

or figuring Africa as the mother of these<br />

different civilizations…Africa is the name of<br />

the missing term, the great aporia, which lies at<br />

the center of our cultural identity and gives it a<br />

meaning which, until recently, it lacked…Such<br />

texts restore an imaginary fullness or plentitude,<br />

to set against the broken rubric of our past.<br />

Hall’s somewhat pessimistic-sounding<br />

take on the role of Africa as the central,<br />

unifying concept of all Black identity interprets<br />

this idea of a singular, underlying<br />

yet shared self as one of two approaches<br />

to cultural identity. Within Pan-Africanism,<br />

this approach was the primary means of engendering<br />

the desire for unity and the sense<br />

of shared urgency on which Internationalist<br />

movements of every sort depended. Though<br />

theorists of subsequent generations, including<br />

Hall, would argue against this method of<br />

binding and thus, as they assert, limiting Black<br />

identity, the necessity of this stance in the time<br />

in which it found its greatest use is not difficult<br />

to understand. Without a central image of<br />

shared concern to bind them, coordinated<br />

activist movements among African descendants<br />

of many lands would have been nearly<br />

impossible to create, much less sustain.<br />

Coming out of this moment however, the<br />

establishment of Black Studies as a burgeoning<br />

field in the late ’60s and early ’70s shifted<br />

the focus from international unity around<br />

the symbol of a free African homeland, to a<br />

series of competing nationalisms. Within this<br />

context it is similarly possible to understand<br />

Hall’s push to investigate difference given that,<br />

as a British citizen of African descent, he was<br />

himself equally marginalized in studies of both<br />

Black and British culture at that time.<br />

In the U.S., approaches to Black Studies<br />

emerging from various Black Nationalist<br />

movements, such as Maulana Karenga’s Us<br />

Organization tended to privilege the study<br />

and culture of African Americans specifically.<br />

At the same time, the reification of<br />

English particularism within British cultural<br />

studies established the subject of that study<br />

firmly, if not exclusively, as the white, British,<br />

male. Though Hall was a prominent figure in<br />

the field and an important voice in such discussions<br />

as a founding member of the Centre<br />

for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham<br />

University, for countless others<br />

across the world the combination made it<br />

difficult to establish Black identity across,<br />

and in some cases, even within national<br />

boundaries.<br />

94 aphrochic issue five 95

Reference<br />

Hall’s work makes a powerful intervention<br />

into the theoretical basis from which<br />

society is observed with the 1980 essay, “Race,<br />

Articulation, and Societies Structured in<br />

Dominance.” Though the term ‘diaspora’<br />

appears nowhere in the text, it is in this essay<br />

that Hall most thoroughly lays out the idea of<br />

difference in unity as entailed in the Althusserian<br />

concept of Articulation. As Hall recounts<br />

the idea:<br />

The term Articulation is a complex one,<br />

variously employed and defined…[I]t is a<br />

metaphor used to indicate relations of linkage<br />

and effectivity between different levels of all sorts<br />

of things…[T]hese things require to be linked<br />

because, though connected, they are not the same.<br />

[Therefore] the unity formed by this combination,<br />

or articulation, is always, necessarily a complex<br />

structure.<br />

The challenge that Hall continued to take<br />

on in his work on cultural identity was to find<br />

a means of expressing the connection between<br />

Diaspora cultures while affirming their difference<br />

— yet without resorting to nationalist<br />

or ethnic “essentialisms.” He describes what<br />

he affirms as a second approach to cultural<br />

identity as one that, “recognizes that, as well<br />

as the many points of similarity, there are also<br />

critical points of deep and significant difference<br />

which constitute ‘what we really are’; or<br />

rather — since history has intervened — ‘what<br />

we have become.’ ”<br />

His recognition of the importance of<br />

the intervention of history in the process<br />

of creating cultural identity achieves two<br />

major goals. First, it dismisses the hegemonic<br />

unity of the African center of the global Black<br />

culture by acknowledging that the passage of<br />

time and the events of history have resulted<br />

in the emergence of new cultures within the<br />

Diaspora which are African in origin — and<br />

then only in part — but not in expression.<br />

Secondly, it emphasizes the differences that<br />

stand between Diaspora cultures while recognizing<br />

the points of similarity that transcend<br />

attempts at facile ethnocentrisms. While additional<br />

scholars would continue the work of<br />

establishing difference as the fundamental<br />

element of Diaspora, Hall’s work was a major<br />

first step towards an understanding of global<br />

Black identity that acknowledged both the<br />

connection of community and the distinction<br />

of unique cultural and historical trajectories.<br />

The Point of it All<br />

In the first article of this series, we looked<br />

at the prevalence of the term diaspora, its attachment<br />

to dispersals of all kinds and the<br />

tendency for those who study them to try to<br />

define diasporas collectively. And we demonstrated<br />

several points of distinction between<br />

the African and other diasporas in the process<br />

of arguing that diasporas in general should<br />

be considered individually as each has its<br />

own salient characteristics. In the transition<br />

away from Pan-Africanism, the global<br />

community now collectively understood as the<br />

African Diaspora created one of its biggest and<br />

most important distinctions, and a massive<br />

argument for its continued study as a thing<br />

unto itself.<br />

The difference between Pan-Africanism<br />

and the African Diaspora as expressed in<br />

their most basic, core concepts is profound.<br />

Both acknowledge a connection between all<br />

Black people and cultures around the world,<br />

as well as points of difference that distinguish<br />

us one from another. But they differ greatly<br />

in their interpretation of this agreement<br />

and on which aspect of the relationship is<br />

most important. For Pan-Africanism, which<br />