LOLA Issue Two

Issue Two of LOLA Magazine. Featuring the people and stories that make Berlin special. Peaches, DENA, Roc Roc-It, Pornceptual, Andreas Greiner, Pansy, Coco Schumann and more.

Issue Two of LOLA Magazine. Featuring the people and stories that make Berlin special. Peaches, DENA, Roc Roc-It, Pornceptual, Andreas Greiner, Pansy, Coco Schumann and more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSUE 02 A/W 2016

LOLAMAG.DE

FREE

+

Thomas von Wittich

Roc Roc-It

Real Junk Food Project

DENA

Pornceptual

Andreas Greiner

Pansy

Symphoniacs

Coco Schumann

Culture Night Belfast

Pit Bukowski

RUBBING BERLIN

UP THE RIGHT WAY

Have you ever danced to classical music?

SYMPHONIACS

A NEW DIMENSION IN CLASSICAL

AND ELECTRONIC MUSIC

A NEW

GENERATION OF

YOUNG CLASSICAL

VIRTUOSOS

VIVALDI MEETS

DAFTPUNK?

Das Album des Ausnahme-

Projekts · 11 Tracks

WWW.symphoniacs.com

Autumn/Winter 2016

Editorial

‘WE’RE ALL ON THIS

RIDE TOGETHER’

On a typical U-Bahn journey in Berlin there

is the distinct chance that you will brush

up against anyone from any walk of life.

The carriages are like a microcosm of the melting

pot that is the metropolis. Hardcore punks sit beside

full-on drag queens, suited and booted office

workers stand alongside street musicians. Young,

old, rich, poor, every nationality, every religion,

every background – everyone is on the U-Bahn,

and let’s not forget the dogs. It’s a democratic experience

that we’re all in together.

This same diversity of life and people in Berlin

is something that we aim to reflect in the pages

of LOLA. In this issue a characterful sideshow

performer, a talented classical virtuoso, a renowned

drag queen, an international music star,

an award-winning artist, a legendary jazz swinger

and more are all hanging out alongside each other.

Of course, it’s not a perfectly representative mix of

the breadth of culture present in the city, but we’re

still at the early stages of our journey, and there are

many more stories to be told.

Every person we feature has a different connection

to Berlin and a different story that ties

them to the city. Of course there are overlaps and

similarities, but for everyone there is some special

hook that has brought them here, that holds

them, and inspires them to stay. Whether that is

the freedom to express yourself in ways that your

country of origin doesn’t allow, to work in a space

where you can develop your artistic practice

without limits, or the ability to live and survive

in an anarchistic Wagenplatz, everyone has their

reasons and motivations.

So the next time you are on the U-Bahn, take a

look around and think about the stories you can

see and the lives people are living. You never know

who you might be sitting beside. Jonny

Publisher &

Editor In Chief

Jonny Tiernan

Executive Editor

Marc Yates

Associate Editor

Alison Rhoades

Sub Editor

Linda Toocaram

Photographers

Fotini Chora

Zack Helwa

Julie Montauk

Viktor Richardsson

Robert Rieger

Tyler Udall

David Vendryes

Writers

Hamza Beg

Brian Coney

Alex Rennie

Nadja Sayej

Jana Sotzko

Stephanie Taralson

PR & Events

Emma Taggart

Special Thanks

Leila Bani

Greg Dennis

Paul Irwin

Jack Pendleton

Lilian Syrigou

LOLA Magazine

Blogfabrik

Oranienstraße 185

10999 Berlin

For business enquiries

jonny@lolamag.de

For editorial enquiries

marc@lolamag.de

For PR & event enquiries

emma@lolamag.de

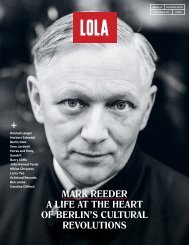

Cover photo by Tyler Udall, jacket by Sara Armstrong.

Printed in Berlin by Oktoberdruck AG – www.oktoberdruck.de

Autumn/Winter 2016

1

2 Issue Two

Photo by Fotini Chora

Pansy commanding the stage at SO36.

Get the full story of her tireless passion

for drag on page 30.

Contents

04. berlin through the lens

Thomas von Wittich

“The city appreciates urban art

more than other cities, or at least

it’s fighting less against it.”

8. local hero

Roc Roc-It

“I just give them my tattoo machine

and say, ‘I really like you, please

paint on me.’”

11. Real Junk Food Project Berlin

“It’s always a nice atmosphere, as

cooking and eating together always

creates very strong connections.”

14. DENA

“It’s one thing to appreciate a good

song and another to really be

struck by it.”

16. Pornceptual

“We’re trying to encourage people

to produce their own porn.”

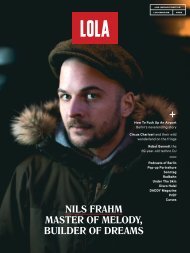

20. cover story

Peaches

“People need to not take it for granted

because it’s still one of the most

free and creative cities in the world.

If people want to pretend it’s a bourgeois

nightmare, then they can just

go away. Don’t treat it that way.”

26. Andreas Greiner

“I’m bringing nature into the

white cube.”

30. Pansy

“It’s really beautiful to see so many

people getting dressed up and

looking silly and being themselves

and doing their thing.”

34. Symphoniacs

“I think a lot of electronic musicians

came up on electronic music, but

to have a Tonmeister – someone

with a classical background – it’s a

completely different approach.”

38. Coco Schumann

“I was the drummer in one of the

hottest, high-octane jazz ensembles

of the entire German Reich.”

42. dispatches

Brian Coney in Belfast

“Every venue and space is emanating

music and life, the art galleries

are rammed with people, and the

atmosphere is electric.”

44. the last word

Pit Bukowski

“For some reason I never watched

Scorsese’s Cape Fear until last week.”

Autumn/Winter 2016

3

Berlin Through The Lens

Thomas von Wittich

“Fun things usually happen when you leave your

comfort zone,” says Thomas von Wittich as he

recalls scaling rooftops and moving trains with

the Berlin Kidz, the latest subjects of his adrenaline-fuelled

photographs. In viewing Thomas’ work,

we get a unique glimpse of Berlin’s street art as it’s

being made, and get to experience the rush of what

it’s like to be there climbing walls with the pros.

BERLIN THROUGH THE LENS:

THOMAS VON WITTICH’S

BERLIN KIDZ

4 Issue Two

Thomas von Wittich

Berlin Through the Lens

To get the perfect shot, Thomas keeps

one eye on the viewfinder and the

other on the easiest escape route, and

in doing so he captures some of the most exciting

scenes of our city in expressive black and

white. Just before his aptly titled Adrenaline

exhibition, we stole some precious daylight

minutes with Thomas to learn more about how

he got in with Berlin’s secretive graffiti crews.

How did you get involved in Berlin’s street

art scene? I left home quite early and had

hundreds of different jobs to support myself

while I spent my free time painting graffiti.

I was a cook onboard a ship, I was loading

trucks, I worked in the meatpacking industry,

I worked in a company making chicken

nuggets, I sold cameras, pumpkin seed oil, and

ice-cream. Then I quit painting and started as

an assistant to a music photographer who was

working in the goth scene.

I spent three years in his studio or at concerts,

taking photos and developing and printing

in the darkroom. When I started to work

as a photographer I was really just shooting

rap artists, which turned out to be the reason

I moved to Berlin: there was not too much

happening in my hometown.

When I came to Berlin, I met Alias and

some other street artists, and I decided to go

out with them at night to take some photos of

them painting. From that point on I started to

shoot more street and graffiti artists and fewer

musicians.

Autumn/Winter 2016

5

Berlin Through the Lens

Thomas von Wittich

What do you feel is special about the

scene in Berlin? The city appreciates

urban art more than other cities, or at least

it’s fighting less against it. On one side it’s

easier to paint in Berlin than in other cities

because of the freedoms; on the other side

it’s harder because of the competition. I

feel like people don’t really work together

or support each other too much.

How did you gain access to the people

you document? When I moved to Berlin

eight years ago I was walking in Kreuzberg

with a good friend I used to paint with and

we saw some of the first Über Fresh (ÜF)

rooftops. He said: “This looks like shit, but

trust me, if they keep going, this will get

interesting.” So I followed their career pretty

much from the very beginning. Three

years ago I tried to make contact but it took

a few months before I found someone to

introduce me. I went to shoot one action

with them and told them that I would be

very interested in following them with my

camera, and a year later they called me

back and said, “OK, let’s go.”

The first action I took photos of after the

call was when they painted the huge façade

in the Cuvry Brache, directly after Blu

let his famous artwork get painted black.

Nobody told me before what was going to

happen, we just met in front and they told

me that they were going to repaint the wall.

And that I would have to climb a bit.

We climbed ‘a bit’ over three pitched

roofs in the dark, rain and cold. It was my

first time walking on a roof, so I followed

them so slowly. When I finally arrived

at the spot, it took like two hours before

they started to paint while I was just

sitting in the rain waiting. The first thing

they wrote on the wall was ‘FUCK YOU

DU FOTZE’. At this point I was questioning

the whole thing, like, seriously? I was

risking my life for that? Until I realised

that an investor wanted to build luxury

apartments with the view of Berlin’s

famous graffiti – the Blu artwork – so they

wanted to make a statement and paint a

huge middle finger for him.

The longer I followed them with my camera,

the more comfortable I became on the

roofs, and when we went on the same roof

some months later I could walk and take

photos at the same time.

Did you have to work hard to gain

their trust? They document pretty much

everything they do by themselves, so it was

nothing really new to them, except for the

6 Issue Two

Thomas von Wittich

Berlin Through the Lens

fact that I was taking photos instead of filming.

I got introduced by a mutual friend and I think

in general I have the image of being trustworthy.

But I had to prove somehow that I was fit

enough to follow them over the roofs, so I was

not a risk for them.

We’ve read that you are pretty fearless in

chasing the perfect shot. Have you ever

put yourself in danger when shooting? I

wouldn’t describe myself as fearless, I just do

what I think is necessary to get the shot I want. I

don’t really feel that I put myself in danger, but

that is relative. They estimated my fitness very

well and told me before whether I’d be able to

manage it, something I knew that I could trust

them on.

Who do you think are the best street artists

working in Berlin right now? I don’t really see

it as a competition, and urban art is in general

a wide field, so I don’t want to point out people

saying they are the best. But I like LES MISERA-

BLES a lot.

Why do you choose to shoot your photos in

black and white instead of colour? I never

did anything else. I started to work as a blackand-white

photographer 12 years ago and I never

felt the need to change. When I shoot urban

artists, I’m not interested in the final colourful

artwork in the streets – there are plenty of photographers

and usually the artists themselves

take care of documenting the work. I want to

show the atmosphere and the circumstances of

how it was created. I want to show the process

and the artists – things you usually don’t see.

For me that works very well in black and white.

Have you always been attracted to subcultures,

or is it this specific moment in street

art that interests you? I have always been

attracted to culture in general. But I grew up

with graffiti, it’s what I know, what I like and

what I completely understand. And I am really

fascinated by the effort people put into creating

their art. Some actions are planned out like

bank robberies, but in the end it’s just to bring

some colour to the city.

Do you have any new projects in the works?

I’m for sure gonna continue to document urban

artists, but at the same time I don’t want to plan

too much. I started two new series in the last

four years which are both unreleased and very

far removed from what I was doing before. I

might just experiment with that for a bit.

Be the first to see Thomas’ latest late-night

adventures by following him on Facebook at

facebook.com/thomasvonwittichphotography

Autumn/Winter 2016

7

Local Hero

Roc Roc-It

LOCAL HERO:

THE STREET LIFE

OF ROC ROC-IT

8

Issue Two

Roc Roc-It

Local Hero

Street performer, cabaret act, circus sideshow, and a true character: Roc

Roc-It’s life has taken him across the world on a wild ride with enough

stories to fill a book. On stage he lives up to his name: a rocket firing on all

cylinders with the crowd in the palm of his hand, but off stage is an entirely

different affair. He’s a livewire, but he also has real softness, warmth

and openness. We meet with him in the infamous Berlin Wagenplatz he

calls home to hear a little about how he got to where he is today.

words by

Jonny Tiernan

photos by

Robert Rieger

Where are you from originally? I was born in the

Black Forest and grew up close to Cologne. It’s a small

town in a little valley – forest on one side and the other

side mountains with vineyards, a river in the middle.

When did you move to Berlin? Eight years ago. I

heard lots about Berlin. When I was 13, me and my

friend were little punk rockers so we decided to run

away. There were two ways we could go: to Hamburg

or Berlin-Kreuzberg. We went to the highway and

hitchhiked, but we didn’t have a clue which way the

highway went. In the end we didn’t get to Berlin or

Hamburg, but instead ended up somewhere south in

a shitty little town. Luckily we knew somebody there

and we managed to sleep under their stairs until our

parents picked us up. We were ready for a revolution

when we were 13. Then we grew up, got girlfriends

and started skateboarding. In the early ‘90s we got

trapped with the techno and the drugs, and the revolution

disappeared a little bit.

How deep into the techno scene did you get? I was

a techno and house DJ back in 1993. I played loads

of parties, and I thought I didn’t need a house, just a

backpack and my record box. The next biggest towns

were Bonn and Cologne, and I actually lived on the

S-Bahn between them. I always made a point that I

would be the last DJ of the night, and after the party

I would go to the subway, put my record box down,

put my feet up, and go to sleep. Then at the end,

somebody would wake me up and tell me it was the

last stop, I’d change platforms, take the train back and

sleep. I did this for a whole year.

What did you do next? I did a winemaking apprenticeship

in the mountains. On my test scores I was the

third best winemaker in Germany. From there, I went to

school to become a winemaking master.

And how did you get started as a performer? Some

friends of mine were organising a party and wanted a

fire breather. I knew a guy, but then I couldn’t get hold

of him. I was doing some fire stuff – not fire breathing

– but I had promised them a fire breather so I decided

to step up and do it. I learned fire breathing for this one

show, but the adrenaline from getting everyone riled up

got me hooked on performing in front of an audience.

How did you make the change from winemaker to

performer? During my summer break from school I

didn’t have any money but I wanted to do something,

so I hitchhiked to Barcelona. On the way there, my

backpack got stolen and I lost everything except my

juggling box and my fire equipment. I was halfway

there, so I decided to keep going even though I had no

money. I spent the first night sleeping on the roof of

a casino, as it had nice padded grass and some palm

trees. In the morning I woke up and I was like, ‘Fuck,

OK, now I’m in Barcelona, I only speak German, I have

a few skills but I don’t have a show, I don’t know anybody,

but hell, I’m here now so let’s see what’s up.’

I randomly walked through the city and I stumbled

upon the Las Ramblas area. Every 20 metres there

was a human statue, a musician, a magician, a street

show, a juggler – the whole street. I thought, ‘Man, this

is fucking paradise, all these people are making money

doing what they love to do, and back home I am walking

up and down the hills carrying heavy shit on my

back. Fuck that, I’m staying here.’ And that’s what I did.

I forgot school, my apartment, my car, and everything

I had back in Germany. All that stuff just wasn’t important

anymore, so I stayed in Barcelona.

Where did you live, and how did you get by? I lived

on a park bench for the first three months. I met a guy

playing didgeridoo, and alongside him I started doing

some fire devil stick, fire breathing and fire eating.

It wasn’t a real show, just didgeridoo, music and fire,

but we made enough money to get some breakfast,

Las Ramblas

A series of short streets

around the tree-lined

pedestrian mall La Rambla.

Spanish poet Federico

García Lorca once said that

La Rambla was “the only

street in the world which I

wish would never end.”

Autumn/Winter 2016

9

Local Hero

Roc Roc-It

beers and tobacco. We met a lot of people

doing other shows and from this I learned

little by little. You meet other people and

you exchange things. Somebody teaches

you a trick, you teach that person a trick,

or you tell that person a joke they can do in

their show. It was a big interaction of people.

We were a really nice crowd of 50 street

performers who were all friends and who

were hanging out all day. There was no competition,

everybody made enough money,

and everybody had a good time. I was like,

‘Forget working in a vineyard, this is what I’m

doing from now on.’ That’s 15 years ago and I

don’t regret a single minute.

Where did you go after the park bench?

I met another street performer who was

living in a squat; he said he was leaving and

his room was free. I didn’t actually know

anything about squatting before that, I

didn’t have any idea of the political scene,

but from there I met people and I started

slowly understanding. Then I carried on and

squatted other buildings.

When did you start getting tattooed? I did

my first one when I was 13 using a compass

and the ink cartridge from my pen to make

a little anarchy symbol on my hand, stickand-poke

style. The ink was shit and I didn’t

go deep enough so it disappeared after a

year, but I had the clear picture of myself

in the future in my head, being completely

covered in tattoos from top to bottom. My

idea was to look like the outside of a fridge

and the inside of a public toilet. So like a

bunch of magnets stuck to the outside of

the fridge, and people writing silly shit with

marker pen on the inside of a public toilet.

That was my whole idea of how I wanted to

look. I think I did a really good job!

Where do you get your tattoos? From really

good friends of mine. Many are from friends

who have never done a tattoo in their life,

they’re not even good with drawing! I just give

them my tattoo machine and say, “I really like

you, please paint on me.” All the bits are more

like memories of people than an art collection.

What’s the story behind your rubber chicken

tattoo? I got that on the TV Show Miami Ink

when they came to the Coney Island Circus

Sideshow. The rubber chicken I had been

using in my act had gone missing. In America

they have milk cartons with missing children

on them, so I got this tattoo of a missing rubber

chicken. I started crying on camera and

said, “If anybody knows anything about my

chicken, please call the Sideshow, I miss him!”

One week later there was a mountain of boxes

addressed to me, and each box had a rubber

chicken inside. I had this giant pile of rubber

chickens that had been sent by people from

all over the country. It was fucking amazing.

How did you end up as part of the Coney

Island Circus Sideshow? I was on a trip to

the States, and during my last two weeks in

New Orleans I split up with my girlfriend. The

police were really on my ass and I couldn’t

make any money. I really liked New Orleans –

the music, the artists, the circus community

are great – but the situation was against

me. I had friends living in New York that I

had squatted with in Barcelona, so I thought

I would visit. On the last day of my visa I

decided to go to Coney Island and do a show

on the boardwalk, just to have one nice show

before I left. I stopped in front of the Sideshow

and the boss came out. I had a suitcase

and on the side of it was written ‘The Roc-It

Circus Sideshow’. He came up to me and said,

“Oh, you do sideshow, what do you do?” I

told him what I did, that my flight was in five

hours but I would love to do my thing on his

stage. He said “OK” and took me backstage.

I had ten minutes before they said, “It’s

your turn.” I got the audience really loud and

rowdy and had a great show. Afterwards

the boss said, “So, your flight is later. That’s

a real bummer because I would hire you for

the summer.” That was the moment I had to

decide. I could either remember the US as a

really shit time and go home, or forget the

flight, stay, and create something. I thought

about that moment on stage and how awesome

it was, about the history of that sideshow,

and I decided to stay. That turned into

three years, doing over 1,000 shows a year.

What about Berlin? Have you noticed it

changing much over the eight years you

have lived here? The streets are getting

more complicated. The police and Ordnungsamt

are coming down on amplifiers, saying

you can’t do shows at certain times in certain

places, that the audience is too big. It’s the

stuff I’ve seen in many other cities in Europe,

and now in Berlin. When I arrived here there

were absolutely no rules. You could come

with a big flamethrower and massive speakers

to any place you want and do a show.

What are you working on next? Next month

I’m booked in Barcelona as a birthday clown

for a three-year-old boy! I do anything: street

perfomance, techno festivals, punk rock

shows, cabarets, burlesque, theatre, circus,

freak shows, whatever! It’s not circus or sideshow,

it’s in between, and that’s why it fits to

absolutely every audience.

There’s no schedule to Roc’s shows and you

won’t find him on Facebook. If you see him

perform, you’re one of the lucky ones.

Rubber Chicken

Johnny Carson reportedly

kept a rubber chicken behind

his desk on The Tonight

Show as a comedic

talisman. It was believed

that “a rubber chicken

always gets a laugh.”

10 Issue Two

Real Junk Food Project Berlin

Sustainable Eating

words by

Hamza Beg

photos by

Zack Helwa

REAL JUNK FOOD

PROJECT BERLIN:

TACKLING

FOOD WASTE

ONE TROLLEY

AT A TIME

In a world where an empty shelf means

a wasted sales opportunity, one wonders

how it is physically possible for us to deal

with the sheer amount of food that is so

quickly restocked and replenished in our

supermarkets. So when the lights go out

and the last cashier has neatly pressed

all the notes into the cash register, what

happens to all of the food edging past its

sell-by date? Tobias Goecke knows and is

trying to change it.

When you first meet Tobias

you might imagine that he’s

achieved almost everything he

set out to achieve with The Real Junk Food

Project Berlin. His calm persona and gentle

demeanour give the impression of an individual

totally at ease in their affairs and

business. However, there is a rag-tag charm

about the project that Tobias began back

in June 2015. Talking with him, it becomes

apparent that the Berlin branch get their

hands dirty, work exceedingly hard and

passionately pursue their goal of bringing

about a radical change in the way we deal

with food waste.

Fact: globally, somewhere near 1.3 billion

tonnes of food is wasted every year. This

means approximately a third of all food

produced in the world is never eaten. It

is a startling fact, and Tobias repeats this

information with the air of a man who still

cannot quite believe it. “I think what I find

heartbreaking is that the resources that go

into food production – land, labour and

everything – in the end is also wasted,” he

says. The problem is almost unmanageably

global and thus the only possible response

is one that grows from the ground up: a

local reaction to a global concern.

Having started cooking at a young age,

Tobias developed an interest in food from

simple but hearty dishes – standard pasta

recipes and potato-based meals. He cooked

with his family, experimented with different

spices and herbs, and still remembers

his first attempt at spaghetti. The tomato

sauce was too watery and the pasta was left

swimming in a red sea of bolognese. There

was more work to be done.

Tobias left his native Prenzlauer Berg

to study social sciences in Halle, and

developed a keen interest in questions of

political and social inequality. He travelled

to South Africa for his diploma research

where he met his wife-to-be. He would stay

for two years before moving back to Berlin

in 2014. “I originally come from a background

in journalism and filmmaking, and

then in Berlin I worked in project management

and cultural management which

was not as fulfilling for me,” he explains.

Something that you learn very quickly after

meeting Tobias is that his idea of fulfilling

work is intimately tied to benefitting his

surroundings.

One such example is the Fair-Teiler

project, an early influence on Tobias that

combined his growing awareness of the

food waste issue and his interest in tackling

inequality. Fair-Teiler, meaning ‘fair-sharer’,

sets up shelves and fridges across cities

and encourages people to leave and take

food from them at will. “I was amazed by

how good the food was,” he begins. “Perhaps

it had one little spot but it was still

fine produce and this was amazing for me.”

When he came across the Real Junk Food

Project however, something struck a chord.

It is hard for Tobias to say whether he

chose the project or the project chose him,

but the facts suggest that he did indeed

Autumn/Winter 2016

11

Sustainable Eating

Real Junk Food Project Berlin

« I THINK WHAT I FIND

HEARTBREAKING IS

THAT THE RESOURCES

THAT GO INTO FOOD

PRODUCTION –

LAND, LABOUR AND

EVERYTHING – IN THE

END IS ALSO WASTED. »

choose it. The Real Junk Food Project rescues

food that would otherwise be thrown

away by big supermarkets, cooks it up into

delicious treats and offers it on a pay-asyou-feel

basis. Having started in the UK,

the project has found legs in various different

locations, and a simple email from Tobias

was enough to bring one into existence

in Berlin. After contacting Adam Smith,

the project’s founder, he was encouraged to

set up in Berlin and through hard graft and

utter dedication, Tobias and his various

volunteers have made it happen.

Tobias’ story and the entire project

itself is replete with an almost bygone

romanticism: “We have arrangements with

two organic supermarkets and we collect

the food that they can’t sell anymore. It’s

always a lot of bread, salad and vegetables

– we usually get a good amount. It’s still a

bit of a drop in the ocean. At the moment

we don’t have a car, so just do it with trolleys

and the train. It’s OK, but there’s only

a certain amount we can carry from the

stores.” He candidly tells us of a time that a

fallen trolley left berries strewn across the

road in Marzahn. The industry and drive it

takes to transport trolleys of food across a

city recalls a time before Berlin’s ubiquitous

DriveNow culture, of which the trolley

is an unmistakeable symbol.

Recognised as one of the greatest markers

of consumer capitalism, the project in Berlin

radically reclaims the shopping trolley.

It moves from being a bound object trapped

within the aisles of a supermarket to a wild,

free-wheeling vehicle for change. Some bizarre

subversion of mass consumer culture

is occurring here as Tobias and his team

fight food waste, one trolley load at a time.

If transportation is the first stage, transformation

is the second. With this plethora

of rescued food, the team find a variety of

different uses for their newly-recovered

resources. The primary aim of the project is

to cook rescued food as a pop-up restaurant.

The team has cooked for a variety of

different events, hosted some themselves

and partnered with other food-sharing

groups in Berlin. But it doesn’t stop there:

“At the moment, as part of the project, we

donate surplus food to other organisations

who provide for homeless people, like

Engel für Bedürftige (Angels for People in

Need). They set up supermarkets in which

they sell this surplus food for a few cents,

redistributing this food to the community.

So we bring them the food, also in trolleys.”

One of the goals of the project could be,

like other Real Junk Food organisations

in the UK, to set up a pay-as-you-feel café.

However, something about the permanence

of a café doesn’t seem to excite Tobias. “It

would be great to have a food truck because

it means you can be flexible and move

around to different locations,” he says. Having

a food truck does seem more in keeping

with the spirit of Tobias’ project, where

12 Issue Two

Real Junk Food Project Berlin

Sustainable Eating

everything is about flow and movement

of food and people, and most importantly

a consciousness about the way we consume.

For Tobias, there is always a duality in

his approach to the project. First, there is

the principle of not wasting – preserving

and respecting the very nature of the food.

This is deeply personal and informed not

just by his work and experience but an

inner belief in having a positive impact on

the world. Secondly, there is the human

aspect, creating connections between

volunteers, encouraging a consciousness

about consumption and finally, feeding

people: “People get together and get to

know each other through the cooking. It’s

always a nice atmosphere, as cooking and

eating together always creates very strong

connections.”

Tobias works with a pool of around 30

volunteers, which is a good indication of

how popular the project is becoming, given

that it is just over a year old. One of the elements

of the work that makes it so exciting

for Tobias, and for all of those who partake

in the project, is the mix of people donating

their time and culinary skills.

“The volunteers are quite an international

team. We have students from Italy

and Spain, and at every event we have a

different team who bring a different mix of

their influences.” Tobias proudly notes that

even their cooks are a diverse mix of experienced

chefs and almost complete amateurs,

making the whole process of volunteering

appear open and incredibly welcoming.

“I am really amazed when the team starts

working to see what they come up with –

it’s like a beehive buzzing.”

The project has also worked consistently

with refugees from the Refugio

Share House, where Berliners and refugees

live together. When moving people means

moving cultures, there is always an opportunity

for exchange and interaction. For Tobias,

the kitchen is the perfect place for that

to happen. He and his team blend Middle

Eastern, South African and European flavours

with whatever other influences their

volunteers bring. “We work with Cooking

for Peace, who also do intercultural cooking

events. I really enjoy that and support it.

We have other organisations that work in

the sustainability field or the social impact

field, so it is becoming a little network.”

Something about Tobias’ approach to the

entire project leaves such a strong impression

that it becomes almost impossible not

to believe in it. Throughout our discussion

he references a number of different

organisations related to the project, and it

becomes clear that the food consciousness

movement in Berlin has a strong backbone

of support. With dedicated figures like Tobias,

it feels as though we are in safe hands,

and yet we should not relax our efforts.

There are trolleys out there that need liberating,

stomachs that need feeding, food

that needs saving and minds that need

changing. He concludes: “For me it is about

appreciating the food and not considering

it just a product that you buy. It is an essential

thing for all of life.” Tobias’ statements

are so sincere and honest that you begin to

question how you have not yet reached the

same conclusions.

If you are interested in attending a Real Junk

Food Project Berlin event, you can follow

them at facebook.com/TRJFPBerlin. For general

information on the global movement, visit

their website at therealjunkfoodproject.org

Autumn/Winter 2016

13

New Music

DENA

words by

Jana Sotzko

photos by

Julie Montauk

CLOSER TO SOME KIND

OF TRUTH: BULGARIAN

POP ARTIST DENA

It’s been four summers since Berlin-based DENA suddenly

showed up in everybody’s newsfeeds. Her breakthrough

track, ‘Cash, Diamond Rings, Swimming Pools’, was a catchy

mix of hip hop beats and Balkan pop in a distinct Bulgarian

accent. The accompanying video was set in a Neukölln flea

market, and it captured the type of ironic, cheap yet irresistible

glamour that is often associated with Berlin.

On an unexpectedly hot late-summer

afternoon, we meet over french fries

and white wine to talk about her

new EP, living in Berlin and the escapist potential

of a great pop song. Despite the heat,

Denitza Todorova, aka DENA, is reflective

and enthusiastic. Her new EP Trust has recently

been released and she is eager to talk

about her musical ideas after having worked

extensively on putting out the new material.

The roots of DENA’s passion for pop

music – the 1990s specifically – can be

traced back to her formative years in the

post-socialist tri-border region of Bulgaria,

Greece and Turkey where she grew

up in a small town. Pirated cassettes and

VHS recordings of MTV shows played a

big role in her musical education, as did

her living situation. Sharing a tiny flat

with her parents and sister, DENA’s early

interest in music had an escapist quality

to it. She elaborates: “There are all these

photos of me when I was little, always with

headphones on, obsessively listening to

Michael Jackson. Listening to music on

headphones created this private space, a

room for myself.” This idea of a headspace

and the physical aspects of hearing music

so close to the ear comes up several times

as we discuss DENA’s own music and the

question of when she considers a track

good enough to release. “You never know

beforehand how a song will resonate with

others. My personal criteria goes back to

that image of me excessively listening to

music through headphones – I want to feel

closely connected to a track.”

Becoming the performer she is today

has not been easy. After leaving Bulgaria,

DENA first found herself studying in

western Germany for a few miserable years.

Unable to pursue any artistic dreams, she

felt stuck and insecure about whether

leaving her home country had been the

right decision: “I was suffering so much

during those first years because German

wasn’t my first language and I couldn’t just

go out there and, you know, present myself.

I was wondering whether I should have just

stayed to apply for the theatre in Sofia.”

Visa regulations (Bulgaria did not join the

EU until 2007) made it impossible to move

unless it was connected with a change of

university. That chance presented itself 12

years ago and DENA gladly took it, ending

up in Berlin quite by coincidence: “Berlin

just happened. I was like, ‘OK, the capital,

that sounds alright!’ The city was surely

already cool in 2004 but still far from the

hype today.”

In terms of finding a means of artistic

expression, the move turned out to be just

what DENA had needed: “I was obsessed

with music and was always writing lyrics. I

just had no idea yet how to combine them

with music. When I came to Berlin I immediately

found myself in bands, and that

link between lyrics and sound was finally

there.” She started playing live, founded

her own label, met producers and fellow

artists, and then in 2012 ‘Cash,

Diamond Rings, Swimming

Pools’ happened. “I didn’t play

it for ten months to anyone

after I’d made it. It was more

of a personal exercise and then

I really was surprised that of

all the songs I’d ever written,

Mocky

Former member of

Peaches’ rock band The

Shit with many notable

co-writing credits and

production collaborations

including Feist, Mary J.

Blige, Chilly Gonzales,

and Jamie Lidell.

this was the one that people wanted to hear

the most. That really says a lot and I’m not

sure if it’s a good thing or a bad thing,” she

laughs. The video was also initially a happy

accident. It was supposed to be shot in

Bulgaria but when the budget turned out

to be too tight, she chose a Neukölln flea

market instead. YouTube viewers and the

local media embraced the result as a representation

of what makes the city special.

Looking back, DENA seems grateful, yet

unsure whether this label was a fitting one.

“I’m thinking a lot about Berlin these days.

When ‘Cash, Diamond Rings, Swimming

Pools’ came out, I was in the right spot at

the right time. It was almost like people

wanted Berlin to be branded. Suddenly it

was easy to say ‘this is Berlin’. I didn’t really

understand it back then. Today I’m asking

myself all the time: what is Berlin?”

The implications of location, hype and

the changing state of Berlin begs another

question: does the city influence her

music? Did it ever? “I would make the same

music elsewhere,” DENA says. “My biggest

fear is that I might make better music

outside of here. I started to really concentrate

on my solo project five or six years

ago. It was in Berlin that I did that. Now I

suddenly feel a strange form of liberty and

freedom outside of here. I guess, though,

that it’s not so much connected to the city

itself than to what I am used to. If I feel a

bit of stagnation it might just be enough to

change my apartment, actually.”

It therefore comes as no surprise that

the Trust EP was not written and produced

exclusively in Berlin, but also in New York

and Los Angeles. Take, for example, the

first single, ‘Lights Camera Action’: “I wrote

the whole song on a piano in LA at Mocky’s

house. I was totally in an LA mood at the

time – the lyrics reflect that, too. Then later

in New York my friend played this funky

guitar line over it.” The process of developing

demos and songs over a period of time

is audible on the new EP, which is more

melodic and funky than her earlier releases

and – while maintaining a hip hop-infused

street smartness – also surprises with

classy arrangements and instrumentation.

In the studio, DENA is mindful to keep

everything close to herself while crediting

co-writers’ additions to her songs: “I work

mainly with friends and family. It’s the best

thing ever. I’m actually easy to

convince that something can

work for a song, like in the case

of that funky guitar part or the

horn section in ‘Trust’.” We

talk a bit about the role of the

producer and the challenges

of sharing a song with others

14 Issue Two

Autumn DENA2016

New Editorial Music

« YOU NEVER KNOW

BEFOREHAND HOW

A SONG WILL RESO-

NATE WITH OTHERS. »

– which then brings us back to Berlin as

a creative hub: “I don’t find it difficult to

share my composition with a producer,

otherwise I’d just be sitting in my room

and doing everything on my own. In this

collaborative style we really create pop

music that I enjoy and that is meaningful

to me. Berlin is great for that type of communal

work. It offers a network and community

that doesn’t even always have be

here. It can just be people passing through.

It’s really a blessing and it took me some

years to realise this.”

When asked about her current favourite

musicians from Berlin, DENA is quick

to name Efterklang successor Liima and

Canadian singer Sean Nicholas Savage

as recent inspirations. While she met the

latter at a shared concert in Poland and

immediately felt a connection, her friendship

with Liima has also led to musical

collaborations and mutual remix work.

Whenever DENA begins to talk about music

it becomes immediately clear that she is

still as much a fan as she is an artist. Again,

the liberating potential of a well-crafted

song comes up. “There is something

about the combination of lyrics, melodies

and chords that just stays with you,” she

begins. “It does not happen often but

it can have a physical effect. It’s one

thing to appreciate a good song and

another to really be struck by it. For

example when I first heard Tame

Impala’s ‘New Person, Same

DENA

Old Mistakes’ I couldn’t stop listening to it

on repeat. I was like, ‘this is the most genius

songwriting ever,’ in terms of what he

is saying, the structure, how it sticks with

you. That’s the stuff I’m interested in.”

DENA describes her interest in further

exploring her musical means with visual

arts – adding stylistic tweaks, trying out

new forms and material. In the case of her

new EP, these experiments have led to a

more personal perspective than before. As

the title suggests, the four songs are lyrically

concerned with interpersonal feelings

and communication. Taking on different

perspectives, ideas of trust and attraction

are contrasted with disappointment,

suspicion, and doubt. Tables get turned

before the emotional confusion culminates

in the aptly titled final track ‘I Like You: I

Lied to You’. DENA describes the song as

“an exercise to write from the perspective

of someone else for the first time. I was

practicing different points of view, flipping

them around.” Was she ever worried about

singing rather personal lyrics? Quite the

contrary: “I found it challenging to actually

stop myself from writing things that were

too personal. The EP is my study of not

having filters in terms of honesty. I wanted

to see how it feels to be super personal

about things. I’m interested in writing and

exploring language. With every song I write

I try to get closer to some kind of truth.”

Trust is out now on Normal Surround.

Keep up with DENA’s latest tour dates and

releases at denafromtheblock.com

Autumn/Winter 2016

15

Undressed to Impress

Pornceptual

PORN THIS WAY:

STRIPPING DOWN THE ART AND

POLITICS OF PORNCEPTUAL

Challenging the porn industry with art and simultaneously running one of Berlin’s

hottest queer parties might sound far-fetched, but this is exactly what Pornceptual

is doing. Built by a collective of determined individuals, their project attempts to

reconfigure the way we consume sex and interpret our own sexualities. To better

understand this forward-thinking venture, intrepid journalist Alex gets a first-hand

look at one aspect of the Pornceptual project before meeting the team to learn more.

One thing that never ceases to amaze me

about Berlin is that it’s completely normal

to get up in the small hours of a Sunday

morning and head to a nightclub. Recently I found

myself doing just that, after dragging myself out

of bed and traipsing off to the bathroom. Standing

under the shower, it dawned on me that I’d never

set foot in a sex party. As steam filled the room, the

quasi-virginal connotations of experiencing something

for the first time not only seemed ironic given

the circumstances, but also filled me with a sense of

apprehension.

After a short U-Bahn ride, I alighted at Jannowitzbrücke

and set off towards Alte Münze, an

intimidating building that served as Berlin’s state

mint until the mid-2000s. It wasn’t long before I

spotted a gaggle of people further down Stralauer

Straße who looked like punters – a relief to see

some life after my solitary sojourn. Getting closer,

I noticed a substantial queue. Having bought a

ticket in advance I skipped the line and spoke to

the door attendant, who I’m fairly certain instantly

clocked me as a newbie.

“So what are you going to be wearing tonight?” he

asked. Unsure of what to say, all I could muster was

an unconvincing, “Er, maybe I’ll take my shirt off?”

Answering with a playful laugh and a wry “maybe,”

he ushered me through the door. Crossing the

threshold and into the cloakroom, I was confronted

with the bizarre Neo-Victorian awkwardness of not

words by

Alex Rennie

Left to right; Pornceptual

team members Raquel,

Justus, Chris. Photo

by David Vendryes

16 Issue Two

Pornceptual

Undressed to Impress

knowing where to rest my eyes. People were

stripping themselves of more than their jackets.

The first thing that struck me as I descended

into the old mint’s underbelly was the thick

smell of sweat that filled the air, coupled with

the greasy film of it that clung to the ceiling. As

I weaved through the crowd of revellers, many

of whom were in various states of undress, I

came across an array of debauched attractions,

including a cinema screening arty porno, two

installations and a bordello-style photo booth.

The ensuing rave was a hedonistic maelstrom

of open sex, casual exhibitionism, and loose

dancing, buoyed by a soundtrack of thunderous

techno and pulsating 4/4 house. It was very,

very fun. On the way home a few hours later, I

pondered what it all meant, deeply intrigued to

learn more.

Alte Münze

The building was the state mint for

close to 60 years. In that period it

pressed Reichsmark, Mark der DDR,

and produced post-reunification

currency. Before it shut in 2006, it

was churning out 1 Euro coins at a

rate of 850 per minute.

Top: Photo by Eric and

Chris Phillips from Porn

by Pornceptual. Right:

Photo by Eric and Chris

Phillips from Porn Resistance

by Pornceptual

perspective of a naïve outsider, the tacit carnality

threaded through Carnival and Copacabana

seems anything but inhibited. Apparently that’s

something of a fallacy. “It’s a huge misconception

to think that Brazilians are very free sexually.

It’s one of the most reserved countries when

it comes to sexuality,” Chris explains. “The way

they control sexuality is crazy. A woman can get

arrested on the beach if she goes topless, but at

the same time they sexualise nudity.”

Raquel, who hails from São Paulo, agrees.

“The biggest mistake is when people say Brazil is

such an easy-going nation – it’s not. Everything

is based on the idea that men are further up the

hierarchy than women. And men have the right

to do whatever they want and women have to

just follow,” she says. Chris also explains how

this culture of machismo makes it a dangerous

place for queer people: “Homophobia is rife. I’ve

had so many horrible experiences when I really

feared for my life. I genuinely thought I would be

beaten to death just because of my sexuality.”

This rigid environment inspired Chris to establish

Pornceptual. He says that the project began

as “an online platform for people to show different

sides of their sexuality.” “It felt great that the

project offered me a safe place where I could have

a voice and express myself,” he adds. However,

after a small hiatus, Chris’ decision to move to

Berlin in 2012 afforded him the perfect opportunity

to harness Pornceptual’s latent potential.

There’s much more to Pornceptual than

Caligula-style merrymaking. In fact, when the

project was kickstarted five years ago, parties

weren’t even part of the plan. Eager to get the

scoop, we met with three of Pornceptual’s key

team members: Chris Phillips, Raquel Fedato and

Justus Karl. Sitting in the garden of Kreuzberg’s

Südblock on an unseasonably balmy autumn

afternoon, the trio of twenty-somethings bare all

– figuratively speaking, that is.

Chris, as the founder, is the first to begin on

how Pornceptual emerged in 2011. Originally

from Brasília, he reveals how he initiated the

project in Brazil’s capital as a means of expressing

his own sexuality. “I always say that the

project has a very personal motivation behind

it,” he begins. “I come from a super conservative

and religious background, and I think this really

repressed me sexually.”

Chris’ admission is intriguing; it doesn’t really

fit with the stereotype of ‘sexy Brazil’. From the

Autumn/Winter 2016

17

Undressed to Impress

Pornceptual

Few places can vie with the ultra-liberal

setting that Berlin gifts its inhabitants.

Historically speaking, it’s a city with a

longstanding tradition for being incredibly

accepting and tolerant when it comes

to sexual preferences. In addition, events

like The Berlin Porn Festival, now in its

11th year, showcase a more sundry side to

pornography than the infinite plethora of

hardcore flicks that plague the internet.

Chris agrees that Berlin and Pornceptual

are a match made in heaven. “It was really

important to move to a place like Berlin.

The project is what it is because we’re

here,” he says. “The freedom you get here is

so special. It was great to realise I was in a

city that offers this.”

Though both are Brazilian, Chris and

Raquel got to know each other through

mutual friends soon after relocating to

Germany. “We met at Homopatik and

had this long talk about Pornceptual and

the future of the project,” she explains.

“Chris mentioned he needed someone

who had experience with media and

marketing, which happens to be my

background.” They decided that Chris

would steer Pornceptual’s artistic direction,

and Raquel would preside over the

financial end of things.

Pornceptual’s centrepiece is without doubt

its website. Comprised of a blog and a host of

erotic galleries – both photo and video – the

page is a fleshy cornucopia of artistically

presented figures. With over 32,000 likes on

Facebook and a 14,700-strong Instagram audience,

it also has a substantial social media

presence. The project’s mission statement is

emblazoned across the site’s ‘About’ section:

“Pornceptual presents pornography as queer,

diverse and inclusive. We aim to prove that

pornography can be respectful, intimate and

artistic, while questioning usual pornographic

labels. ‘Can art succeed where porn fails

– to actually turn us on?’”

So why has the porn business become

Pornceptual’s arch enemy? “We want to condemn

an industry that’s plastic, misogynistic

and commercial,” says Raquel vehemently.

Chris adds: “We’re critical of the way the

industry treats people, from production to

the distribution. It’s horrible.” To say that the

porn industry is thriving is a bit of an understatement.

The global porn trade is said to be

worth an estimated $97 billion, and emerging

technologies like virtual reality are opening

new opportunities for growth in 2016 and

beyond. Countless journal articles have also

questioned ‘conventional’ porn’s blatant heteronormativity,

not to mention the dubious,

yet inevitable, educational function it serves

for young people worldwide. This is something

Pornceptual directly opposes.

Curating the photographic content for the

website is pivotal to this objective. “We’re

trying to encourage people to produce their

own porn,” Chris says. “It’s a way of rejecting

the porn industry, especially when people

exchange sexual intimacy through these

images.” Initially, the gallery was solely an

outlet for Chris to exhibit his own work. This

has now become increasingly collaborative,

with work by established artists, amateurs,

and photographs taken at Pornceptual’s parties.

Concerning the latter, Chris adds: “It’s a

way for guests to participate in the project.”

Raquel notes that the only photographers

at the events are Chris and his twin brother,

Eric: “The pictures are taken inside our photo

booth to ensure that anyone who doesn’t

want to be photographed, isn’t.”

Raquel continues by explaining the

struggle of getting a representative

cross-section of models up on the site,

especially when it comes to body shapes.

“Over the next few months we’ll be focusing

on having more diversity on the web

page. Most of the people who’re happy

standing in front of the camera naked tend

to be hot,” she admits. “People who don’t

feel comfortable with their bodies are less

likely to want to pose, and we’ve received

criticism for not representing them.”

Photo by David Vendryes

This kind of reflexivity extends to

Pornceptual’s approach to booking. Having

hosted over 40 events to date, each with a

different theme, the group are keen to ensure

that at least 50% of the acts they roster

are female. “Berlin’s nightlife is sexist,”

Chris claims. “Promoters should book more

girls, but it’s not happening. Even big clubs

like Berghain aren’t doing it.”

Recently, the group launched their

online shop. Showcasing small labels such

as UY Studio’s Berghain apparel, Fifth

Element-style harnesses by London’s Elastigear,

and handcrafted jewellery by French

silversmith Gaëten Essayie (some pieces of

which retail in excess of €600), it’s fair to

say that the store is a bona fide emporium

of fetish wear.

Given Pornceptual’s anti-establishment

positioning and commitment to celebrating

marginalised forms of sexual expression,

it seems a little paradoxical that they’re

selling fetish gear as a fashion accessory.

More to the point, many people approach

BDSM as a way of investigating recesses of

their sexual self that would otherwise stay

concealed. Could the project thus be running

the risk of trivialising a long-standing

subculture and converting it into some-

18 Issue Two

Pornceptual

Undressed to Impress

thing gimmicky for people to flaunt, almost

like fancy dress, at their parties?

Justus, the newest addition to the

Pornceptual team, chips in with a salient

rejoinder. “We’ve been attacked on the

grounds we exploit the fetish scene before,”

he says. “I think it’s a really narrow-minded

stance if you can only see fetish’s so-called

‘realness’ in really hidden spaces. It’s a

weird view on liberating yourself if you can

only partake in fetish behind closed doors.”

Chris is also outspoken when it comes to

this line of critique: “We’re putting fetish

gear in a different context and presenting it

as something you shouldn’t be ashamed to

wear. It’s something you can wear outside

of the fetish scene too. We’re not trying to

change any meanings here.”

Our discussion eventually returns to Pornceptual’s

coveted events. This time, however,

the topic of cultural appropriation arises,

a contentious issue that is by no means confined

to Berlin’s nightlife. Agreed, Pornceptual

isn’t indiscriminately exploiting queer

expressions for material gain. However, are

its loyal partygoers really in tune with the

concept’s underlying principles, or just on

the prowl for Berlin’s next big thing?

“Maybe not all of the people who come,

but I’d say most of them appreciate what

we’re about,” says Chris. “We do have to be

careful, and that’s why it’s important for us

to have a door policy.” Raquel reasons that

cautious selection is central to preserving

the project’s integrity: “We want new

people to join the party. But we also have

to choose the right people. If guests come

with the right mindset and attitude, then

the door is open.” For Chris, it seems that

there’s also an element of protection at

play here. “We don’t want it to become a

tourist attraction,” he admits. “It’s crucial

that people understand the project.”

So what does the future herald for the

ambitious collective? With plans to publish

the third installment of their print magazine,

and proposals to crowdfund a ‘Pornceptual

Academy’ where people can collaborate

with the project offline, things look

characteristically busy. “One day we might

stop being culturally relevant,” says Chris.

“But I truly believe that right now we are,

and there’s still a lot to do.” It’s hard to fault

the ethos behind Pornceptual. Whether it’s

tackling the challenge of queering the porn

industry or throwing a party of unrivalled

decadence, one thing’s for certain: only

in Berlin could such a novel yet relevant

project come into being, and thrive.

Learn more about the project and how you

can get involved at pornceptual.com

«

IT’S A WAY OF

REJECTING THE PORN

INDUSTRY, ESPECIALLY

WHEN PEOPLE

EXCHANGE SEXUAL

INTIMACY THROUGH

THESE IMAGES.

»

Top: Comes Cake. Middle: From ‘Skin

Depth’ by Flesh Mag. Bottom: From

‘Summer Moved On’ by Anton Shebetko.

Left: Photo by Eric and Chris

Philips from Anti-Porn by Pornceptual

Autumn/Winter 2016

19

Cover Story

Peaches

PEACHES

RUBBING BERLIN

UP THE RIGHT WAY

Jacket by Sara Armstrong

20 Issue Two

Peaches

Cover Story

She’s provocative, she’s daring, she’s political; she’s sex,

drugs, and rock and roll. Peaches is back, and with her new

album, Rub, she’s better than ever. A pillar of this city’s musical

landscape and an outstanding example of how it cultivates

talent, here she talks about life, Berlin, making music,

and rolling with the punches.

words by

Nadja Sayej

photos by

Tyler Udall

styled by

Leila Bani

Chilly Gonzales

Pianist, producer, and songwriter

known for high-profile

collaborations with Daft

Punk, Drake and his work

with Berlin-based hip-hop

outfit Puppetmastaz.

At the premiere of Peaches Does Herself, a

rock opera stage show that charted the

Canadian artist’s history through 20 of her

own songs, she stepped onstage at the Hebbel

Am Ufer Theatre in Berlin to a huge unmade bed

illuminated by a spotlight. She hopped onto it in a

tiny pair of pink shorts, grabbed a groovebox and

started hammering out a machine-gun sequence

of bassy beats. The impressive story that unfolded

dates back to her first album, The Teaches of

Peaches, which was recorded in her bedroom on a

Roland MC-505.

In an early interview, Peaches recalled these

musical beginnings: “I was pretty horny at the time

and I was masturbating a lot and smoking dope. I

put the machine on my bed beside me and made

beats. Masturbate, go to the bathroom, smoke dope

and make beats. And record them.” Keen to hear

the rest of the story, we speak with her as she’s on

tour promoting her latest album, Rub, and we ask

Peaches to recall that bedroom, which she says was

in a warehouse, set on an industrial strip in downtown

Toronto: “My apartment had really thin walls.

Anytime I would try and make beats, the neighbour

would call or ring the doorbell and say: ‘Please, the

bass, help stop the bass!’”

Thankfully, she never stopped the bass, but she

did move apartments – and continents. After a stint

living with fellow musician Leslie Feist on Toronto’s

famed Queen Street West, Peaches happily packed

her bags and relocated to Berlin in 2000. “When I

left Canada, there was conservatism happening with

the music and the way I was treated in the underground,”

she tells us. “Chilly Gonzales and I always

called ourselves ‘the weird ones on last’ because

they always put us on at the end of the night. They

didn’t know what to do with our style and music.”

Born Merrill Beth Nisker, Peaches adopted her

stage name from a character in a Nina Simone song

called ‘Four Women’, which features four different

female characters who have struggled through

different troubles. Choosing her namesake from

this powerful anthem allowed her to foreground

her mission; even today, Peaches’ work echoes

Simone’s own struggle to overcome oppression.

But before she became Peaches as we know her

today, she worked as a music and drama teacher at

a Hebrew school in Toronto, teaching during the

day and making music in the evenings. Peaches

started a folk group in 1990s called Mermaid Cafe,

then later a rock group called The Shit. She released

Lovertits, her first EP as Peaches, in 2000 but never

thought her music career would take off. “I wanted

to become a theatre director, that was my dream,”

she says. “I didn’t know anything about art growing

up; there was no musical talent in my family.”

She enrolled in the theatre programme at York

University, but it wasn’t what she expected: “To be

honest, I dropped acid one day and thought, ‘No

way, I want to get the fuck out of this programme, I

don’t want to work with actors, I am going to have a

heart attack by the time I’m 30, this is not what I want

to do.’” She took art classes and fought with many

professors who didn’t understand her approach. She

tackled multimedia from a musician’s point of view,

despite not yet being a musician herself.

On moving to Berlin, Peaches was quickly signed

to Kitty-Yo Records, who released her first bedroom

album, The Teaches of Peaches. Unlike university,

her approach wasn’t questioned in Berlin: “When I

came, it was a big deal what I was doing,” she says.

“It was a kind of sexuality that wasn’t expressed.”

And expressing sexuality is exactly what she did,

in all its brazen glory. One old, black-and-white video

clip of her first Berlin performance has Peaches

standing with her pants undone. She grabs the closest

guy to the stage. “Come here,” she says, “we’re

going to walk around.” She jumps on his shoulders

and continues to sing over an electronic beat as

the man walks stoically through the audience with

Peaches leaning into them with a microphone.

For the uninitiated, The Teaches of Peaches acts as

an introduction to her sound and what she is about,

particularly the album cover, which features a photo

of her crotch in pink booty shorts. The album’s

first track, ‘Fuck the Pain Away’, became a huge

hit. She laughs at how she introduces the song at

concerts nowadays as a ‘Canadian classic’, because

it wasn’t always that way. Peaches started playing

underground shows in Berlin alongside acts like

Cobra Killer, who were decidedly experimental.

Autumn/Winter 2016

21

Cover Story

“They were two girls from the digital hardcore scene,

they did really raw performances, electronic music

that was just screaming,” she recalls. “They were loud,

messy, throwing red wine everywhere. I felt I’d found

my inspiration.”

Since that first release, she’s made a name for

herself by breaking down musical clichés and flipping

the script on sexuality. One might consider her a mix

between the French performance artist Orlan and the

American sex-ed therapist Dr Ruth – always fascinating,

yet educational beneath a veil of humour.

Her stage persona is certainly memorable – a

long, blonde mullet with shaved sides, paired with

pink eye make up that stretches past her temples.

It’s a throwback to Divine, the drag queen who

found cult fame in the films of John Waters. Peaches’

gender-bending performances fuse the fearlessly

unconventional with sexy prose – a stage presence

which is deeply rooted in performance art. We wonder

why she chose pink. “I wore a pink bathing suit

because I thought it was offsetting my aggression on

stage,” she explains. “It was weird and cheap.”

«

THEY WERE LOUD, MESSY,

THROWING RED WINE

EVERYWHERE. I FELT I’D

FOUND MY INSPIRATION.

»

At the time of her first release in the early 2000s,

Berlin wasn’t yet a cultural fairy tale – Berghain didn’t

exist until 2004 and the Euro wasn’t introduced until

2002, Spätkaufs only sold booze and there was no pizza

delivery service. Peaches used her Chausseestraße

apartment to record the music video for her song

‘Red Leather’ with Chilly Gonzales. “I didn’t have any

carpet and it had just turned 2000, so I got this carpet

that said ‘Happy New Year’ in every language with

champagne bottles all over it,” she remembers.

In 2003 her second album, Fatherfucker, was

released, its title a counter-attack on ‘motherfucker’.

Subverting misogynistic, heteronormative or otherwise

problematic terms became her trademark; she

uses the word ‘clit’ in songs where men might boast

about their dicks, and she’s no stranger to using vagina-shaped

costumes.

Backstage in the early years, Peaches could often

be found grabbing a fat black Sharpie and smiling as

she signed fans’ asses and tits. She became known for

encouraging everyone to show their own sex appeal,

and laughs that she created a whole new cliché. She

has been called an angry feminist: “In a way, it was

good for me, people were like ‘Oh no, yikes! I better

not piss her off!’ or they were into it,” she says. “But

I experienced it in a technical way at shows, like, ‘Do

you know what you’re doing?’”

22 Issue Two

Cover Story

Jacket by Manish Arora,

skirt by Sara Armstrong

Autumn/Winter 2016

23

Cover Story

Peaches

Much has changed since Peaches got

her start 16 years ago, especially Berlin.

“Everything has changed,” she says. Which

isn’t necessarily a bad thing: “There is

actually a thriving music scene.” It wasn’t

always that way: “The reason it was ‘underground’

was because there weren’t a lot

of people to meet,” she adds. “And nobody

mixed rock and electro, nobody ever

played rap; there was no rap whatsoever.

Until 2009, there was just German rap.” She

remembers DJing at White Trash Fast Food

and playing rock and electronic together

in the same set: “It was the early 2000s and

people were almost too afraid to mix stuff,

now it’s so standard.”

Although many might suggest that

Berlin’s once-thriving music scene is now

dead, Peaches appears tired of hearing it.

“A lot of people say that’s when the scene

died, some people will say when the Wall

came down the scene died,” she says.

“People say when the 2000s came, that’s

when it died. People just keep saying it.”

However, she is quick to defend the music

scene. “It’s still a great scene, there’s still a

lot going on in Berlin,” she asserts. “People

need to not take it for granted because it’s

still one of the most free and creative cities

in the world. If people want to pretend it’s a

bourgeois nightmare, then they can just go

away. Don’t treat it that way.”

When Berlin gained momentum as the

capital of cool in the late noughties, tons of

North Americans started flooding the lowrent

city. It was then that Peaches released

her fifth album, I Feel Cream, in 2009. Here,

she popularised the art-pop that Lady

Gaga later became known for. In the video

for ‘Take You On’ she gallivants around a

Matrix-like grid with a large Amish beard

while wearing a puffy, glowing outfit. Let

it be said that Peaches did strap-ons and

stage blood long before Lady Gaga took a

more mainstream approach. In challenging

the status quo with gender-bending, Peaches

offers a less conventional perspective.

Maybe people are afraid of her – she has yet

to be on any late-night talk shows (aside

from The Henry Rollins Show) and doesn’t

get booked for big festivals like Coachella

because her work is too sexually explicit.

That’s not to say she’s a pornographer,

or even a dancing gender theorist. While

Peaches counts influences such as ‘no wave’

writer Lydia Lunch, Kathleen Hanna’s

punk band Bikini Kill and Kat Bjelland’s

group Babes in Toyland, she offers a lighter

delivery – a sense of humour. Perhaps this

is why Peaches relates to comedians more

than she does to musicians: humour helps

get the feminist message across.

Despite her rising popularity, Peaches

doesn’t see herself as a celebrity; rather, she

says that the approach journalists take has

changed. She’s an artist who has always had

to prove herself as people hound her with

inane questions: does she take music seriously?

Is she a shock jock using sex for attention?

Does she hate men? Now, she says,

the media has accepted her: “Right now, I’m

important as a trend. When young people

interview me, they say I’m a pioneer. But I’m

not more important than I was before; I’ve

been doing it a while so it’s just what happens.”

Being a trend seems to be something

that she’s not entirely comfortable with. “It’s

weird for me to be called ‘important’ rather

than trying to be understood,” she says.

“We’ll see how long that lasts.”

After a five-year hiatus from music while

she focused on theatre and film, Peaches

came out of the musical darkness to release

another album, Rub, last year. Still pushing

sexual boundaries with tracks like ‘Pickles’,

where she sings about giving birth without

an epidural, and ‘How You Like My Cut’,

referencing pubic hair, she seems to be

24 Issue Two

Peaches

Cover Story

« I ALWAYS SAY THAT I WANT

TO LIVE IN LA IN THE DAY

AND BERLIN AT NIGHT. »

aligned with more star power on this album. There are

tracks, for example, with Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon,

and Feist. The video for ‘Dick in the Air’ has Peaches

running around Los Angeles alongside comedian

Margaret Cho, the two of them wearing fake penises.

They put on condoms and penetrate a watermelon.

When people call out Peaches for having penis envy,

she corrects them: she has hermaphrodite envy.

Her videos for Rub have caused controversy: ‘Light

in Places’ had aerial artist Empress Stah performing

with a green laser buttplug, while the video for ‘Vaginoplasty’

had synchronised swimmers wearing vagina-shaped

wigs. The music video for ‘Rub’ also earned

itself an ‘explicit content’ flag on YouTube, thanks to a

lesbian orgy scene.

One has to wonder if all the fuss isn’t actually about

content, but the fact that the person in these ‘inappropriate’

videos happens to be a woman. According to

Peaches, sexism isn’t over in the music industry. “Music

is still a patriarchal world and the music industry is

still run by old white men,” she says. Take her recent

song, ‘Dumb Fuck’. It won’t get any radio play because

of its language, while Big Sean’s ‘IDFWU’ – with the

lyric “you little stupid ass bitch I ain’t fucking with

you” – has been widely played on mainstream radio.

“Take down the patriarchy,” says Peaches, calmly, a

mission clearly at the core of her values.

While she is still pushing buttons, some Berliners

are packing up and leaving the city. Is it still the coolest

city in the world? With luxury developments and

gentrification pushing out the independent art scene,

Stattbad Wedding – a swimming pool-turned-cultural

centre where Peaches had her former music

studio – closed down last year after complaints