Kurt Schwitters: Merz (2016) – Norman Rosenthal interviews Damien Hirst

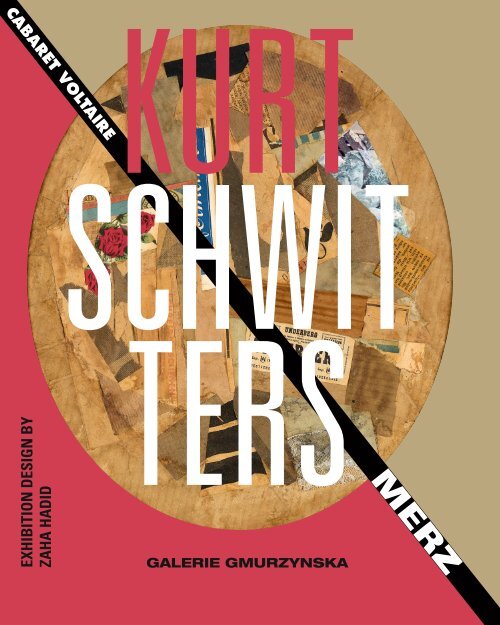

Fully illustrated catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska in collaboration with Cabaret Voltaire Zurich on the occasion of Kurt Schwitters: MERZ, a major retrospective exhibition celebrating 100 years of Dada. The exhibition builds and expands on the gallery’s five decade long exhibition history with the artist, featuring exhibition architecture by Zaha Hadid. Edited by Krystyna Gmurzynska and Mathias Rastorfer. First of three planned volumes containing original writings by Kurt Schwitters, historical essays by Ernst Schwitters, Ad Reinhardt and Werner Schmalenbach as well as text contributions by Siegfried Gohr, Adrian Notz, Jonathan Fineberg, Karin Orchard, and Flavin Judd. Foreword by Krystyna Gmurzynska and Mathias Rastorfer. Interview with Damien Hirst conducted by Norman Rosenthal. Includes full color plates and archival photographs. 174 pages, color and b/w illustrations. English. ISBN: 978-3-905792-33-1 The publication includes an Interview with Damien Hirst by Sir Norman Rosenthal about the importance of Kurt Schwitters's practice for Hirst's work.

Fully illustrated catalog published by Galerie Gmurzynska in collaboration with Cabaret Voltaire Zurich on the occasion of Kurt Schwitters: MERZ, a major retrospective exhibition celebrating 100 years of Dada. The exhibition builds and expands on the gallery’s five decade long exhibition history with the artist, featuring exhibition architecture by Zaha Hadid.

Edited by Krystyna Gmurzynska and Mathias Rastorfer.

First of three planned volumes containing original writings by Kurt Schwitters, historical essays by Ernst Schwitters, Ad Reinhardt and Werner Schmalenbach as well as text contributions by Siegfried Gohr, Adrian Notz, Jonathan Fineberg, Karin Orchard, and Flavin Judd.

Foreword by Krystyna Gmurzynska and Mathias Rastorfer.

Interview with Damien Hirst conducted by Norman Rosenthal.

Includes full color plates and archival photographs.

174 pages, color and b/w illustrations.

English.

ISBN:

978-3-905792-33-1

The publication includes an Interview with Damien Hirst by Sir Norman Rosenthal about the importance of Kurt Schwitters's practice for Hirst's work.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

KURT<br />

SCHWIT<br />

TERS<br />

EXIBITION DESIGN BY<br />

ZAHA HADDID<br />

CABARET VOLTAIRE MERZ<br />

EXHIBITION DESIGN BY<br />

ZAHA HADID<br />

ZURICH<br />

GALERIE GMURZYNSKA

KURT<br />

SCHWITTERS<br />

Volume I

KURT<br />

SCHWIT<br />

TERS<br />

galerie gmurzynska<br />

20th century masters since 1965<br />

w w w · g m u r z y n s k a · c o m

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>. MERZ<br />

June 12th to September 30th <strong>2016</strong><br />

Exhibition architecture by<br />

Zaha Hadid<br />

In collaboration with<br />

Cabaret Voltaire,<br />

Adrian Notz<br />

Celebrating 100 years of<br />

Dada Zurich<br />

Presented at the original location<br />

of the first DADA exhibition

“In part spurred by Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm, [Jasper] Johns<br />

made a point of studying <strong>Schwitters</strong>’s work in the collection of<br />

the Museum of Modern Art. In many ways, Johns suggested,<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> was the first Dada figure to have significant impact<br />

on his thinking, preceding even Duchamp.”<br />

Leah Dickerman, the MoMA Marlene Hess Curator of Painting and Sculpture, („<strong>Schwitters</strong> Fec.,” in<br />

Isabel Schulz (ed.), <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>. Color and Collage, The Menil Collection, Yale University Press, New<br />

Haven and London 2010, p. 88.<br />

We can safely assume that no artist living today was not, one way or another, influenced<br />

by <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>. Galerie Gmurzynska’s continued fascination with <strong>Schwitters</strong> dates<br />

back 45 years, when in 1971 Antonina Gmurzynska organized her first in depth survey of<br />

the German Avant-Garde, featuring an impressive selection of <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ works. Over<br />

the years the relationship with <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ son, Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>, became a close<br />

friendship and large-scale one-man exhibitions of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ oeuvre would follow<br />

throughout the history of the gallery up to this date. A particular highlight was the 1980<br />

solo-show of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ work in Paris at the FIAC, which was the first time that a<br />

substantial retrospective by the artist had been shown in France.<br />

With <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> MERZ we sought to expand this history and transport it to the<br />

21 st century. This major retrospective exhibition brings together a unique selection of<br />

seventy works across all media; including key works of each period, many of which have<br />

been especially loaned from significant collections.<br />

Presented in a fully transformed gallery space designed by the late Pritzker Price winning<br />

architect Zaha Hadid, this collaboration resulted from the idea of an architectural homage<br />

by Zaha Hadid to the famous ‘<strong>Merz</strong>bau’ of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>.<br />

With Galerie Gmurzynska’s unique Zurich location in the same building complex where<br />

100 years ago the first DADA exhibition took place, celebrating this centennial, the<br />

retrospective is realized in curatorial collaboration with the Cabaret Voltaire, where the<br />

DADA movement originated in 1916.<br />

An exhibition of this scale owes its existence to many individuals and institutions. We<br />

are most fortunate for all the support we have received working on this once in a lifetime<br />

retrospective.

The project was only made possible by an extraordinary partnership with late Zaha Hadid<br />

and Zaha Hadid Architects, who have allowed us to reimagine the legendary ‘<strong>Merz</strong>bau’<br />

Gesamtkunstwerk as part of this retrospective timely presented for the Dada centennial<br />

in Zurich. We are therefore deeply thankful to Patrik Schumacher, the visionary torch<br />

bearer of Zaha Hadid Architects, Maha Kutay, Woody Yao, Melodie Leung and Filipa<br />

Gomes to name but a few.<br />

Our utmost gratitude must go to all authors for this important book, many of whom<br />

created texts exclusively for this publication, acting as true collaborators in delineating new<br />

approaches to see <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ multifaceted oeuvre and revealing his great importance<br />

spanning an inexhaustible array of genres and media. We extend special thanks to<br />

Norman <strong>Rosenthal</strong>, Flavin Judd, Adrian Notz of Cabaret Voltaire, Prof. Dr. Sigfried Gohr,<br />

Dr. Jonathan Fineberg and Dr. Karin Orchard.<br />

We are extremely grateful to <strong>Damien</strong> <strong>Hirst</strong> for his exclusively insightful interview<br />

underlining the absolute importance of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> as a game changer of 20 th century<br />

art and his enduring influence on all contemporary art today.<br />

For her relentless help and all the supportive information about the connections of<br />

Malevich and <strong>Schwitters</strong> we are very grateful to Jewgenija Petrova, Deputy Director of<br />

the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. We extend our particular gratitude to Dr. Karin<br />

Orchard and Dr. Isabel Schulz, Sprengel Museum Hannover, for their continuous help<br />

with all the comprehensive and extremely important research facilitating the overarching<br />

number of image requests.<br />

In their essential assistance for the catalog providing saliently scarce documents and<br />

images our greatest debt must be to <strong>Kurt</strong> und Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong> Stiftung, Hanover;<br />

Bauhaus-Archiv Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin; Graphische Sammlung der ETH Zürich;<br />

Tate, London; Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript<br />

Library, New Haven; RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis, Den Haag;<br />

Historic England Archive, Swinden; National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; Hammer<br />

Museum, Los Angeles and the Menil Foundation, Houston.<br />

We are also extremely grateful to all the private and institutional lenders, without their<br />

support this exhibition would not have been possible.<br />

Krystyna Gmurzynska & Mathias Rastorfer

SUMMARY<br />

10 MERZ (Extract from “ARARAT” December 19, 1920)<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

14 i (A Manifesto), Sturm, Vol. 13, No. 5, 1922<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

16 Anna Blossom has Wheels<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> (1942)<br />

18 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> photo album<br />

32 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, as writer, poet and lecturer<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong> (1958)<br />

40 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

Werner Schmalenbach (1980)<br />

46 Introduction to the life and work of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

Siegfried Gohr (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

56 The consequence of Dada: MERZ<br />

Adrian Notz (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

76 <strong>Schwitters</strong>: Tending the Enchanted Garden<br />

Jonathan Fineberg (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

88 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>: A genius in friendship<br />

Siegfried Gohr (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

100 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>: Guestbook of the Ernst and Käte Steinitz family, 1920-1961<br />

110 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> & Kazimir Malevich<br />

120 The Eloquence of Waste<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ work and its reception in America<br />

Karin Orchard (2000)<br />

138 How to look on Modern Art in America<br />

Ad Reinhardt (1961)<br />

140 <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>: I urgently recommend that everybody<br />

buy their Christmas presents now<br />

Norman <strong>Rosenthal</strong> (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

148 Norman <strong>Rosenthal</strong> in conversation with <strong>Damien</strong> <strong>Hirst</strong> (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

154 Double Bladed Axe<br />

Flavin Judd (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

159 Chronology<br />

167 Selected Bibliography<br />

173 Solo Exhibitions

MERZ<br />

(EXTRACT FROM “ARARAT” DECEMBER 19, 1920)<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

10

One could make up a catechism of means of expression, were it not pointless, as pointless as<br />

the intention of expressing a meaning through a work of art. Every line, colour, shape has its<br />

distinct meaning. Every combination of lines, colours and shapes expresses a distinct meaning.<br />

The meaning can only be expressed by this special combination, it cannot be translated. One<br />

cannot render the meaning of a picture in words, just as one cannot paint the meaning of a word,<br />

the word ‘and’, for example.<br />

What a picture expresses is, however, so important that it is worth consistently striving for.<br />

Every attempt to depict natural forms detracts from the power of consistency in working out the<br />

expression. I rejected any reproduction of natural forms and painted only using pictorial forms.<br />

These are my abstractions. I harmonised the components of a picture with one another, just as I<br />

had done at art school, only not in the cause of reproducing nature, but in the cause of expression.<br />

Now even the striving for expression in a work of art seems to me harmful to art. Art is a basic<br />

concept, exalted as the deity, inexplicable as life, indefinable and purposeless. The work of art is<br />

created by the artist’s devaluing of its components. I only know how I do it, I only know my material<br />

on which I draw, I do not know for what purpose.<br />

The material is as unimportant as I am. What matters is the shaping of it. Because the material<br />

does not matter, I use anything to hand, if the picture requires it. As I can arrange different kinds<br />

of material to go together, I have a distinct advantage over pure painting in oils: in addition to<br />

juxtaposing colour with colour, line with line, form against form etc. I can also match material<br />

against material, say wood against sacking. I call the philosophy that gave rise to this kind of<br />

artistic creation “<strong>Merz</strong>”.<br />

The word “<strong>Merz</strong>” had no meaning when I invented it. Now it has the meaning I have given it. The<br />

meaning of the term “<strong>Merz</strong>” changes with the changing consciousness of those who continue to<br />

work within the meaning of the term.<br />

<strong>Merz</strong> demands freedom from any restriction for the process of artistic creation. Freedom is not<br />

unbridled licence, but the outcome of a strict artistic discipline. <strong>Merz</strong> also implies tolerance<br />

regarding any limitation on artistic grounds. An artist must be permitted to compose a picture<br />

entirely out of pieces of blotting paper, as long as he has the power to create. To reproduce<br />

natural elements is not important to a work of art. But representation of actual objects, inartistic<br />

in themselves, can make part of a picture, when integrated with the other parts of it.<br />

I have previously also gone in for other art forms, poetry, for instance. The basic ingredients of poetry<br />

are letters, syllables, words, sentences. Evaluation of these ingredients against one another creates<br />

poetry. The sense is only important where it is evaluated as one more factor.<br />

I evaluate sense against nonsense. I prefer nonsense, but that is just a personal affair. I feel sorry for<br />

nonsense, because hitherto it has hardly ever been artistically shaped, that is why I love nonsense.<br />

11

Here I must mention Dadaism, which like me cultivates nonsense. There are two groups of Dadaists,<br />

the Core- and the Shell-Dadas, of which the latter reside mainly in Germany. Originally there were<br />

only Core Dadaists, the Shell-Dadaists under their leader Huelsenbeck shelled themselves off<br />

from this core, and in the splitting tore away parts of the core. The shelling took place to the<br />

accompaniment of loud howling, singing of the Marseillaise, and the dispensing of kicks by the<br />

elbows, a tactic Huelsenbeck employs to this day. Dadaism under Huelsenbeck became a political<br />

affair. The well-known Manifesto of the Dadaist Revolutionary Central Committee of Germany<br />

demands the introduction of extreme Communism as a Dadaist requirement. Huelsenbeck in his<br />

History of Dadaism of 1920, published by Steegemann, writes: “Dada is a German bolshevik affair”.<br />

The Central Manifesto mentioned above also calls for “the most brutal war against Expressionism.”<br />

Further, in the History of Dadaism Huelsenbeck writes: “Art should really be punishable by<br />

flogging.” In the introduction to the recently published Dada Almanac Huelsenbeck writes: “Dada<br />

carries on a sort of anticulture propaganda.” It follows that Shell-Dadaism is politically orientated,<br />

against art and against culture. I am tolerant and every man is welcome to his own opinions, but<br />

I must just mention that such views are foreign to <strong>Merz</strong>. On principle <strong>Merz</strong> works for art alone,<br />

because no man can serve two masters. However, “the Dadaists’ conception of Dadaism is very<br />

varied”, as Huelsenbeck himself admits. Thus Tzara, the leader of the Core Dadaists, writes in the<br />

Manifesto Dada 1918: “Every artist produces his own work in his own way,” and further: “Dada is<br />

the trade mark of Abstract Art.” I should mention that <strong>Merz</strong> is linked by close ties of friendship to<br />

this form of Core-Dadaism and to the art of the Core-Dadaists Hans Arp – whom I particularly love<br />

– Picabia, Ribémont-Dessaignes and Archipenko. Shell-Dada, in Huelsenbeck’s own words, “has<br />

made into God’s buffoon.” Whereas Core-Dadaism clings to the good old traditions of abstract<br />

art. Shell-Dada “foresees its own end and laughs at it”, while Core-Dadaism will live as long<br />

as art itself. <strong>Merz</strong>, too, aspires to art and is against kitsch, even deliberate kitsch on principle,<br />

even where under Huelsenbeck’s leadership it calls itself Dadaism. Not just anybody, lacking any<br />

discrimination in Art, may write about art: “quod licet jovi non licet bovi”. <strong>Merz</strong> fundamentally and<br />

vigorously rejects the inconsequential and dilettantish views on art of Herr Richard Huelsenbeck,<br />

while giving official recognition to the above-mentioned views of Tristan Tzara.<br />

At this point I must clear up a misunderstanding, which could arise through my friendship with<br />

certain Core Dadaists. One might think that I consider myself a Dadaist, especially as the jacket<br />

of my book of poems Anna Blume, published by Paul Steegemann, mentions the word “dada”.<br />

Drawings on the same cover show a windmill, a head, a locomotive going backwards, and a man<br />

suspended in the air. All that means is that in the world inhabited by Anna Blume, where people<br />

stand on their heads, windmills turn and steam engines go backwards, that also exists. To avoid<br />

being misunderstood, I have put the word “Antidada” on the cover of my Cathedral. That does not<br />

mean that I am against Dadaism, but that in the world there is also a counter current to Dadaism.<br />

Engines may drive from the front or the rear. Why should an engine not go backwards for once?<br />

I have sculpted as long as I have painted. At present l am doing <strong>Merz</strong> sculptures: a fun gallows<br />

and a cult pump. <strong>Merz</strong> sculptures, like <strong>Merz</strong> pictures, are assembled out of a variety of materials.<br />

They are intended as all-round sculptures and be viewed from any angle.<br />

12

<strong>Merz</strong> House was my first piece of <strong>Merz</strong> architecture. Spengemann writes about it in Zweeman<br />

8—10: “I see <strong>Merz</strong> House as a Cathedral: the Cathedral. Not church architecture - no, a building<br />

as the expression of a truly intellectual view of what elevates us to the eternal: absolute art. This<br />

Cathedral cannot be used. Its interior is so filled with wheels that human beings can find no room<br />

in it... that is pure architecture, whose only purpose is as a work of art.”<br />

Trying out various art forms was an artistic necessity. The reason was not an urge to extend the<br />

range of my activities, but the desire to be, not a specialist in one art form, but an artist. My aim is<br />

the <strong>Merz</strong> total work of art, uniting all forms of art in one artistic unity. As a start I have assembled<br />

poems out of words and sentences such that the rhythmic–order produces a drawing. Conversely,<br />

I have stuck together paintings and drawings from which sentences can be read. I have nailed<br />

pictures in such a way that in addition to the painted effect there is a three-dimensional effect.<br />

This was done in order to blur the boundaries of the art forms.<br />

MERZ by <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

13

i<br />

(A MANIFESTO)<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> (1922)<br />

Any child todays knows what <strong>Merz</strong> is. But what is? i is the middle vowel<br />

of the alphabet and the sign for <strong>Merz</strong>’ grasping of artistic form, taken to<br />

its highest degree. <strong>Merz</strong> makes use of large ready-made complexes to<br />

form a work of art. These materials shorten the distance from intuition to<br />

the realisation of an artistic idea, reducing loss by friction. i reduces this<br />

distance = zero. Idea, material and work of art are one and the same. i<br />

comprehends the work of art in nature. The act of creation means here the<br />

recognition of rhythm and expression in a part of nature. Thus there is no<br />

loss through friction; no distractions can occur during the creative act.<br />

I postulate i, not as the sole art-form, but as a special form. In my exposition<br />

in May 1922 in “Der Sturm” the first i-drawings were shown. For Messieurs<br />

art-critics, I must add that naturally much more skill is required to extract a<br />

work of art from unformed natural material than to put together according<br />

to one’s own artistic principles a work of art from just any material; it needs<br />

only to be formed into a work of art. The material for i is however, not so<br />

easily found, since not every piece of nature is artistically formed. Thus i is<br />

a special form. For once it is necessary to be consistent. Can an art-critic<br />

grasp that?<br />

Der Sturm Volume 13, number 5, 1922<br />

14

15<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> (ed.), <strong>Merz</strong> 2. Nummer /i/, <strong>Merz</strong>verlag, Hanover April 1923

ANNA BLOSSOM HAS WHEELS<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> (1942)<br />

O Thou, beloved of my twenty seven senses, I love thine!<br />

Thou thee thee thine, I thine, thou mine. – we?<br />

That belongs (by the side) not here!<br />

Who art Thou, uncounted woman? Thou art – art Thou –<br />

People say, Thou werst, -<br />

Let them say, they don’t know, how the churchtower stands.<br />

You wearest your head on your feet and wanderst on your hands,<br />

On thy hands wanderst Thou.<br />

Hallo thy red dress, clashed in white folds,<br />

Red I love Anna Blossom, red I love Thine!<br />

Thou Thee Thee Thine, I Thine, Thou mine, – we?<br />

That belongs (by the side) in the cold glow.<br />

Red Blossom, red Anna Blossom, how say the people?<br />

Price question:<br />

1. Anna Blossom has wheels.<br />

2. Anna Blossom is red.<br />

3. What colours are the wheels?<br />

Blue is the colour of thy yellow hair.<br />

Red is the whirl of thy green wheels.<br />

Thou simple maiden in everyday-dress,<br />

Thou dear green animal, I love Thine!<br />

Thou Thee Thee Thine, I Thine, Thou mine – we?<br />

That belongs (by the side) in the glow box.<br />

Anna Blossom, Anna, A—N—N—A<br />

I trickle your name.<br />

Thy name drops like soft tallow.<br />

Does thou know it, Anna, does thou already know it?<br />

One can also read thee from behind,<br />

And thou, thou most glorious of all,<br />

Thou art from the back, as from the front:<br />

A—N—N—A<br />

Tallow trickles to strike over my back.<br />

Anna Blossom,<br />

Thou drippes animal,<br />

I – Love – Thine!<br />

16

17<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>. Anna Blume. Dichtungen (Silbergäule), Paul Steegemann Verlag, Hanover 1919

t<br />

KURT SCHWITTERS<br />

P H O T O A L B U M<br />

Some pages from <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ family<br />

photo album, photographed and pasted<br />

by <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

t<br />

18

t<br />

Page from <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ family album: <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> reciting the Ursonate,<br />

photographed by Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

19<br />

t

t<br />

20<br />

t

t<br />

21<br />

t

t<br />

22<br />

t

t<br />

23<br />

t

t<br />

24<br />

t

t<br />

25<br />

t

t<br />

26<br />

t

t<br />

27<br />

t

t<br />

28<br />

t

t<br />

29<br />

t

t<br />

30<br />

t

t<br />

31<br />

t

KURT<br />

SCHWITTERS<br />

AS WRITER, POET AND LECTURER<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong> (1958)<br />

32<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong> in Lysaker, 1937.<br />

© bpk / Sprengel Museum Hannover /<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>

Almost all the pioneers of modern art of the<br />

late, nineteen tens, the ‘Great Twenties’, and<br />

the early thirties tried to achieve ‘Universal<br />

Art’. Few only reached such a degree of<br />

versatility as did <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>.<br />

Born June 20th, 1887 in Hannover,<br />

Germany, in the ‘Golden Age’ of business<br />

and bourgeoisie, <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> had a<br />

conventional background and upbringing.<br />

At high school he was a brilliant pupil,<br />

particularly in mathematics! In drawing —<br />

art appreciation did not, as yet, exist in school<br />

terminology — he was not above normal but<br />

he had already made up his mind.<br />

After his matriculation in 1908 he attended<br />

the Arts and Craft School at Hannover for<br />

a year, then studied at the Academy of Art<br />

in Dresden from 1909—1914, with one<br />

intermediate guest-year at the Academy of<br />

Berlin.<br />

His studies were interrupted by World<br />

War One, and — in his own words —<br />

he “gallantly fought on all fronts of the<br />

Waterloo Place”, Hannover’s exercising<br />

ground. He succeeded in making so much<br />

of a fool of himself and everybody else, that,<br />

to the “military mind”, he seemed mildly<br />

“touched”, and was, henceforth, released<br />

from military duty. Instead he was drafted to<br />

draw machines till the end of the war.<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> hated the war and the false<br />

ideals it fought for. When peace, at last,<br />

came, the revolutionary search for a better<br />

future, for truer ideals, for a strong, functional<br />

culture inspired him immensely, and from the<br />

very start he was in the forefront of cultural<br />

development.<br />

In 1918 he rounded off his interrupted<br />

studies in painting and drawing by a year<br />

of architectural studies at the Technical High<br />

School at Hannover. “How”, he said, “I will<br />

have to ‘unlearn’ and start working!”<br />

Already in 1917 his first abstract pictures<br />

had been painted. 1918 saw the birth of his<br />

later so famous technique of collage, which<br />

he called “MERZ” (and, incidentally, of my<br />

own self.—)<br />

MERZ-collages were stuck, nailed, in<br />

fact built of a large variety of hitherto —<br />

for purposes of creating art — unlikely<br />

bits of refuse, used as splotches of colours,<br />

movement, form, in completely abstract<br />

compositions. “Nothing is too Iowly to be<br />

used as factors in a composition, in fact, age<br />

and signs of wear induce their own patina<br />

of beauty.”<br />

I believe, it is true to say, that my father<br />

saw the great beauty of weariness, tiredness,<br />

ruin, which surrounded him everywhere<br />

after the war, and of the inherent qualities<br />

of these characteristics, to rebuild a better,<br />

sounder more honest culture. Beyond this, no<br />

“symbolism” should be read into his work as<br />

a painter. He created for the sake of beauty.<br />

He made pure compositions.<br />

However, a parallel developed in his<br />

writing, and, particularly during the first,<br />

dadaistic period, there was a great similarity,<br />

as far as concerns the use of apparently and<br />

conventionally useless bits of ‘rubbish’: bits<br />

of advertising, proverbs etc., sentences, cut<br />

into nonsense, all recombined into a new<br />

composition. But — in this dadaistic writing,<br />

there definitely was a deeper meaning,<br />

however ‘nonsensical’ it appeares at first<br />

sight.<br />

As much of it is bound to geographical<br />

localities and to its particular time, it is<br />

33

KURT SCHWITTERS AS WRITER, POET AND LECTURER · by Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

34<br />

sometimes difficult for ‘outsiders’ to read<br />

sense into the apparent nonsense. But the<br />

general aim of my father’s early dadaistic<br />

writing is, to utterly destruct, by ridiculing<br />

and by subtle sarcasm, the false and hollow<br />

sentiment of decadent bourgeois culture,<br />

thus ‘plowing the ground’, as it were, for the<br />

seeds of a sounder culture. To achieve this,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> often used the very same false<br />

sentiments of bourgeoisie, but so interspersed<br />

with hilarious nonsense, that the hollowness<br />

was clearly exposed. Yet, the average<br />

bourgeois was so foxed by this method, that<br />

he simply declared <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> “mad”!<br />

— A wealth of this writing exists. It was<br />

published as books by the Hannovarian<br />

publisher Paul Stegemann, and appeared<br />

in the avantgardistic magazine Der Sturm,<br />

Berlin, as well as in a great variety of similar<br />

cultural magazines throughout Europe, and,<br />

finally, in <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ own magazine<br />

MERZ, all in those ‘revolutionary’ years<br />

1918 to approximately 1923.<br />

The poem An Anna Blume (To Eve<br />

Blossom) can safely be said to having<br />

been the most successful and, to date, most<br />

well-known work of this period of <strong>Kurt</strong><br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong>’ literary work. It was the highlight<br />

of my father’s traditional ‘MERZ-evenings’<br />

— lecture- and recital-evenings — at his<br />

home in Hannover, regularly attended by<br />

Hannover’s ‘intelligencia’, and by artists<br />

and art-interested people from all over the<br />

world. Eventually, in 1927, the Süddeutscher<br />

Rundfunk (the southern German Broadcasting<br />

Co.) had my father recite this poem and<br />

his equally famous Sonate in Urlauten in<br />

Frankfurt a/M, and recordings were made<br />

simultaneously. 1<br />

The original recording by my<br />

father, recorded here, starts off the present<br />

l/p record.<br />

An Anna Blume is a conventional<br />

bourgeois love declaration, of course, so<br />

subtly is this done, that it simply exposes<br />

the hollowness, and forces us smile at<br />

our own futility.<br />

During these turbulent years of cultural<br />

development <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> came into<br />

contact with, and eventually collaborated<br />

closely with many of the leading Dadaists as<br />

Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara, Theo van Doesburg,<br />

Raoul Hausmann and others. When a section<br />

of the Dadaists, with Richard Huelsenbeck<br />

in the lead, took a pro-communist political<br />

turn, <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> called a definite stop. In<br />

the famous Manifest Proletkunst (Manifesto<br />

Proletarian Art), signed by Arp, my father,<br />

Cristoph Spengemann and Tzara, these<br />

leading Dadaists clearly state, that art<br />

cannot, by definition, be political.<br />

“If a politician creates art, he is not a<br />

politician any more, but an artist, without<br />

relation to any particular ‘class’. Art is not<br />

created for or by any particular ‘class’. It is<br />

above such matters of moment.” Conversely:<br />

if art has a political tendency, it is not art<br />

any more, but political propaganda! How<br />

the lurid, clear logic of this manifest must<br />

have shocked all those good people, who felt<br />

so secure in their belief, that the Dadaists,<br />

and with them <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, simply were<br />

“madmen”! And how it shocked into violent<br />

aggressiveness those Dadaists of the time,<br />

who were unable to separate Socialism from<br />

the honest search for a new culture and<br />

cutural expression! —<br />

But the time had come, to end subtle<br />

destruction, and to rebuild instead. In a more

‘constructivist’ period, which, also in <strong>Kurt</strong><br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong>’ collages, painting and sculptures,<br />

extends from about 1923 to about 1928,<br />

he slowly, but with great consequence and<br />

concentration, builds up a totally abstract<br />

‘sound-poem’, the famous Sonate in Urlauten<br />

(Sonate in Primeval Sounds), the second<br />

part of this I/p. The creative spark came in<br />

1921, when, during a lecture tour to Prague,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, for the first time, heard<br />

Raoul Hausmann’s sound-poem fmsbw. He<br />

immediately recognized the potentialities of<br />

this new form of expression, and he recited it<br />

constantly, during his lectures, as “A portrait<br />

of Raoul Hausmann”.<br />

Over the years the Sonata grew, both in<br />

volume and variation, until it had little or no<br />

resemblance to Raoul Hausmann’s original<br />

poem. It was no more a poem, in fact, but<br />

music — spoken by mouth! The original<br />

fmsbw had long since become “fümms<br />

böwötää zääuu — rögiff — kwiiee!”, and<br />

was merely part of one of the many themes<br />

of the Sonata, now. My father’s lively interest<br />

in music helped him a lot, here.<br />

I shall never forget those many ‘MERZevenings’,<br />

where, as a four-, five-, six-yearold,<br />

I used to have my regular place in the<br />

centre of the front-row of seats, directly<br />

opposite my father, marvelling openmouthed<br />

at him. —<br />

It was during these evenings, that the<br />

Sonata grew. It never was read off a<br />

manuscript, although, in its various stages of<br />

development, it had been published in artmagazines<br />

everywhere. But my father knew<br />

it by heart, and preferred to improvise the<br />

recital, as this gave him the chance to develop<br />

it continuously. Thus a great many people<br />

became witnesses of the slow development<br />

of this unique piece of — shall we say —<br />

‘music’ and/ or abstract poetry.<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> had realised all along,<br />

that a phonetic way of noting down the<br />

Sonata was essential, if it should not die<br />

with him. Ordinary notes, as used for music,<br />

would not do here. With each successive<br />

publication he improved on the form of<br />

notation, and finally, in 1932, the Sonate in<br />

Urlauten was published as his last number of<br />

the MERZ magazine, no. 24. But, although<br />

this is undoubtedly the most phonetic way<br />

of notation to date, it is virtually impossible<br />

to recite it correctly, simply by reading it. A<br />

prime necessity is, that one has heard <strong>Kurt</strong><br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> recite it as often as possible.<br />

This is the reason why, ‘under pressure<br />

from all sides’, I have finally agreed to try<br />

to recite it as best I can. I am fully aware,<br />

that my recital can, in no way, be compared<br />

with my father’s. But then, I am only reciting,<br />

not creating. I must not improvise! Moreover,<br />

I have a different voice, particularly in<br />

volume! Even though, as a lecturer, l am<br />

quite used to speak concise, and to ‘cover’ a<br />

large audience.<br />

But you try to do it better! — There is, at<br />

least, one point I have in favour of all others:<br />

I have got the Sonate in Urlauten — so to<br />

say — with my ‘mother’s milk’. I have heard<br />

it at least 200—300 times! I have closely<br />

followed it’s development. I have immensely<br />

admired it, as I have admired my father. I<br />

believe, I shall never forget the intonation<br />

and pronunciation of it, as I also would never<br />

be able to forget, how to walk! Anyhow, it is<br />

the best I can do. —<br />

Concurrent with the development of the<br />

35

KURT SCHWITTERS AS WRITER, POET AND LECTURER · by Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

36

Sonata and after the Dadaists period, <strong>Kurt</strong><br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> wrote numerous poems of a style,<br />

slightly reminiscent of Morgenstern: rhythmic,<br />

humorous, and sometimes ironical, but always<br />

understanding, positive, friendly. Also his<br />

well-known ‘Grotesques’ developed in these<br />

years: 1923—1933. Some were humorous,<br />

some outright sarcastic, particularly when<br />

they criticised certain unhealthy aspects of<br />

contemporary life and thinking, like militarism,<br />

hero-worship, etc.<br />

A very typical side of his literary work during<br />

this time were his dialectic grotesques. They<br />

usually developed out of some mild irritation<br />

over a very talkative person. The most wellknown<br />

ones are undoubtedly Der Schirm (The<br />

umbrella), Schacko (The name of a pet parrot),<br />

Main näiääs Hutt (My new hat, Hungarian-<br />

German accent. The ‘original’ is Prof. Breuer<br />

of the Bauhaus, a friend of my father’s), Die<br />

Amerikanerin (The American Lady) and the<br />

hilarious Kleines Gedicht für große Stotterer<br />

(A little poem for great stutterers).There is<br />

one thing in common with all these works,<br />

as also with the poems and the Sonata: they<br />

developed slowly, improvised, as they were,<br />

during <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ MERZ lectures, and are<br />

very dependant on a correct, but very specific<br />

intonation and pronounciation. Usually,<br />

they were first written down after years of<br />

improvised recitation, when my father felt sure<br />

of the final form. Some were, unfortunately<br />

never written down at all, and only an all too<br />

vague memory of them remains in my ears.<br />

The problem of a phonetic way of noting<br />

down the intonation and pronunciation of<br />

my father’s literary work has baffled him<br />

throughout his life, and, finding no solution,<br />

many later works have, unfortunately, never<br />

appeared in print at all. Fortunately, they exist<br />

as manuscripts in his hand, and, I believe,<br />

l am still able to recite them as close to the<br />

original as is humanly possible. Eventually,<br />

they have to be recorded, at least on tape.<br />

1933 and the advent of Hitler almost<br />

brought the end of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ litterary<br />

work. He could, of course, not any more<br />

publicize anything in Germany. In 1934 his<br />

many earlier, published works were amongst<br />

those, destroyed during the Autodafee. In<br />

January 1937 he finally fled from Germany<br />

and lived and worked in his home in Lysaker,<br />

near Oslo, Norway. But, although he had<br />

lived in Norway for longer and longer<br />

periods every year, since he first visited that<br />

beautiful country in 1929, he never learned<br />

Norwegian so fluently as to be able to write<br />

in Norwegian. Only very few Norwegian<br />

poems exist in manuscript, one of them —<br />

Vamos — (the name of a dog) a wonderful<br />

sound-poem, even for those who do not<br />

understand Norwegian, although the content<br />

of the poem, too, is very touching.<br />

Then the Nazis invaded Norway, too, on<br />

April 9th 1940, and we both left the country<br />

for England. My father spoke English since<br />

his high school days, but, to write poetry or<br />

even prose in a ‘learned’ language is quite a<br />

different thing to speaking it, even relatively<br />

fluently. However, he did write a number of<br />

English poems, which appear concurrently in<br />

a little booklet: published by my authority by<br />

the Gaber Bochus Press.<br />

37<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>, Photograph of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> in a boat at the foot of a glacier, 1935<br />

© Tate, London 2015

KURT SCHWITTERS AS WRITER, POET AND LECTURER · by Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

38

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

Photograph of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

painting near Djupvassjytta,<br />

Norway, 1933<br />

© Tate, London 2015<br />

39

WERNER SCHMALENBACH<br />

KURT<br />

S C H W I T T E R S<br />

(1980)<br />

!<br />

40<br />

When <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> died in exile in England early in1948, there were few in<br />

Europe who noted the fact. His name was not prominent in the annals of recent art<br />

history. True, he was not totally forgotten in his home town of Hanover, which at that<br />

time lay in ruins. There were many still alive who had known him, to whom he had been<br />

an experience. But there was little question of mourning ‘a famous son of this town’.<br />

People mainly recalled the former enfant terrible, the many turbulent scenes and highspirited<br />

escapades with which this man had alarmed good citizens of his birthplace.<br />

Only a few were aware that a great artist had died, and no commemorative exhibition –<br />

in Hanover or anywhere else in the world –honoured his memory, which was kept alive<br />

solely in the United States, and even there was restricted to a few small circles.

All this changed at a stroke with the first great <strong>Schwitters</strong> Exhibition held in the spring<br />

of 1956 by the famous Kestner-Gesellschaft art society in Hanover, once a favourite of<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> himself, and thereafter shown in the public galleries of Amsterdam, Brussels<br />

and Berne. The work of the artist’s whole lifetime, a large part of which had been hidden<br />

away in unopened cases somewhere near Oslo ever since <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ emigration, for the<br />

first time saw the light of day. The exhibition moved like a triumphal procession through<br />

Europe: the startling revelation of an artist who had been noticed with amusement in his<br />

time, but never regarded as an outstanding figure of modern art. Now <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ name<br />

was on the map, no longer merely as an artistic clown and scourge of the bourgeoisie<br />

who had presided over his one-man- Dadaism more than 30 years ago in Hanover<br />

(albeit with some reverberations in the rest of Europe), but the name of one of the most<br />

considerable artists of his time.<br />

The time was ripe for him now: otherwise he would hardly have had such a sudden<br />

incendiary effect. In the late Fifties a strong neo-Dadaist element was emerging – a<br />

reaction against Abstract Expressionism – with such artists as Robert Rauschenberg<br />

and Jasper Johns. In France at the same time there was a parallel movement which<br />

called itself “Nouveau Réalisme” and also harked back to Dada. Everywhere collage<br />

and montage were making a comeback, scrap materials were invading the art scene; it<br />

was no longer the ‘law of chance’ that governed the movement of the brush, as with the<br />

Abstract Expressonists, but the choice and juxtaposition of all possible and impossible<br />

everyday objects and waste materials; and new – old – names were appearing in the<br />

artists’ precursors’ gallery: beside the Surrealists, with their cult of the ‘objet trouvé’<br />

and their ideology based on the principle of free association, there were two above all<br />

who are venerated to this day as the fathers – or grandfathers – of recent art: Marcel<br />

Duchamp and <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>.<br />

Duchamp and <strong>Schwitters</strong>: without those two, both of whom had stopped working<br />

by 1950 – one by a conscious decision, the other through death – no history of art after<br />

1950 could be written.<br />

It was mainly the early, Dada-orientated <strong>Schwitters</strong> who influenced and entranced the<br />

public and, above all, other artists in that historic atmosphere around 1960: the large-scale<br />

collages of the Twenties – MERZ pictures, as <strong>Schwitters</strong> called them – with their decayed<br />

ingredients, their flaunted disorder and their secret order, and their expressive intensity,<br />

which was decidedly left over from the Expressionism which <strong>Schwitters</strong> had briefly breezed<br />

through just before; and also the hundreds of small-sized collages of all kinds of waste paper,<br />

their brilliant play between wilfulness and will, accident and law, form and its dissolution.<br />

With all this <strong>Schwitters</strong> entered deeply into the consciousness of contemporary artists. Any<br />

mention of <strong>Schwitters</strong> usually referred to this early ‘classical’ phase of his work.<br />

41!

KURT S C H W I T T E R S · by Werner Schmalenbach<br />

!<br />

42<br />

El Lissitzky, <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, 1924<br />

Gelatin silver printphotograph, 11.43 x 10.16cm<br />

© <strong>2016</strong>. Christie’s Images, London/Scala, Florence

As the world changed, as the way of looking changed, so did the view of <strong>Schwitters</strong>’<br />

work – or rather, it expanded. Increasingly <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ contribution to the Constructivist<br />

Movement of the Twenties began to be appreciated. At the same time it was clear that this<br />

contribution was only valid where it was not a question of pure Constructivism or strictly<br />

geometric art, in other words, where <strong>Schwitters</strong> could remain himself. To this scintillating,<br />

vividly alive, essentially unorthodox and above all humorous spirit the dogma of the<br />

right angle must have seemed a starvation diet. <strong>Schwitters</strong> did enter into the Geometric<br />

Abstractions and Constructivism of his Friends – van Doesburg, Lissitzky, Moholy-<br />

Nagy – and adopted the principles of de Stijl and the Bauhaus; but in his best work he<br />

transmuted these into something completely different: montages rather than constructions,<br />

assemblages of raw materials rather than artefacts; a few pieces of driftwood found on the<br />

North Sea shore rather than clean units of construction. The constructive had to embrace<br />

the elements of destruction, decay and accident, nor did <strong>Schwitters</strong> think it sacrilege to<br />

deviate from the right angle. Thus there were controversial elements, where others clung<br />

to dogma: intuition instead of planned construction, invention rather than gospel. Yet<br />

that too was a contribution to the Constructivist avant-garde of that time. And as neo-<br />

Constructivist trends were surfacing everywhere during the Sixties, naturally enough in<br />

this context, too, <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ name was retrospectively established.<br />

But what about the later<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong>? The one who<br />

gradually grew away from his<br />

homeland, who ultimately,<br />

after spending several months<br />

of every year in Norway, never<br />

returned to Hitler’s Germany<br />

again, but lived out the last few<br />

years of his life - 1940—1948 –<br />

as best he could in England,<br />

cut off both in space and<br />

time from that international<br />

avant-garde with which he<br />

had once felt so completely<br />

at home. This late work, like<br />

the late works of many artists,<br />

tended to be dismissed with a<br />

shrug. The collages might be<br />

accepted, but hardly the larger<br />

works, of which he did many<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>, Unsere Insel (Island of Hjertøya where<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> and Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong> lived), undated<br />

43!

KURT S C H W I T T E R S · by Werner Schmalenbach<br />

in England. People deplored that the collages were colourful, less witty, less pointed,<br />

and less appealing to the eye. As for the large assemblages and object-reliefs, they were<br />

felt to lack everything that had given beauty to the early MERZ works. The writer of this<br />

article felt very much the same when arranging the <strong>Schwitters</strong> Retrospective in Hanover<br />

in 1956, and when writing the long monograph on the artist which was published in<br />

1967. But soon afterwards I had to revise my opinion and realise that the late work was<br />

of equal importance to the earlier.<br />

!<br />

44<br />

Once again this change of opinion coincided with a general change in visual focus,<br />

presumably influenced by new developments in the field of contemporary art. A new<br />

movement was emerging, which, whatever view one might take of it, imperceptibly<br />

modified and transformed vision. Heralded by artistic events of the Fifties – in that<br />

sector of ‘informal art’ where one might place a painter like, say, Antoni Tàpies – a<br />

movement developed which has been termed ‘Arte povera’. <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ work, with its<br />

preference for ‘moyens pauvres’, fell into this category from the start; but the term<br />

applies more specifically to the late works. There the poverty-stricken materials are<br />

left to their own devices, no longer, as in the early works, aesthetically refined and<br />

transmuted. No enchanting magic of colour is allowed to make its effect now; no assets,<br />

however modest, of colours, tones, harmonies, are brought into play. It no longer seems<br />

the purpose of these works to give the spectator aesthetic pleasure. The works have lost<br />

their musical quality, certainly, but they seem to have gained in humanity. Casualness,<br />

shabbiness, insignificance: all these mark the late works even more than the earlier,<br />

since the qualities are no longer displayed as an amusing stylistic invention, but as the<br />

true expression of the artist’s own life, long devoid of happiness. Where the early collages<br />

mainly have the air of light-hearted studies in a style, the later ones seem an extension<br />

of life itself, without any thought of ‘style’: a life that has lost its glitter and its carefree<br />

attitude. This foreshortening of the distance between art and life, which became so<br />

prevalent in the Sixties and Seventies, probably contributed as much as the rise of ‘Arte<br />

povera’ to the rediscovery and revaluation of the later <strong>Schwitters</strong>. The early works, with<br />

their great artistic confidence and their seductive charm, were now confronted by the<br />

late work, with its decrepitude, its melancholy, a self-confidence no longer unshaken.<br />

There might still be outrageous new departures and daring innovations, but they were<br />

not supported by the general trend of the time or the former fruitful companionship of<br />

like-minded peers. The whole must be seen against the background of a lonely artist<br />

in exile and a world shaken to its basic foundations. Only in a much later, posthumous<br />

climate of opinion could this work make its full effect: today!<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong>, when he first made his mark immediately after the First World War,<br />

had declared that the important thing was to build a new world out of the ruins. That

45!<br />

was exactly what he had done, in the most literal sense: he had picked up the pieces –<br />

discarded objects, litter, rubbish – and had ‘built’ his pictures out of these. Yet he always<br />

maintained that, for all the apparent lack of rules, what mattered to him was form, and<br />

form alone.<br />

‘Form’ was the vital concept for him; and of course that was why, a few years later,<br />

he was able to ally himself to Geometrism and Constructivism. But then, when his world<br />

was shattered for the second time, he could no longer react with gaiety and confidence.<br />

The tenor of his art became one of resignation, the drive of inspiration more laboured.<br />

The pictures, the assemblages, the collages grew more sombre, and, perhaps because of<br />

his own suffering, more humanly touching. Even the large MERZ pictures of the early<br />

Twenties had already been essentially serious: there was a lifelong constant of seriousness<br />

in <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ art. Conversely, the constant element of playfulness persisted, in spite of<br />

everything, to the very end of his life. He himself said it, after all, with resignation: “We<br />

play until Death comes for us.”<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong>’ art until around 1930 was<br />

in the highest degree a contemporary, and<br />

contemporarily aware, art. It was supremely<br />

up-to-date, both in its Dadaist and then in<br />

its (more or less) Constructivist phase. Such<br />

contemporary relevance in youth may be<br />

essential to, but can never be a guarantee<br />

of, survival. In this appreciation, written<br />

more than 30 years after <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ death,<br />

the survival, the posthumous influence<br />

of <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ work, has been linked<br />

with ‘contemporary’ trends: with Neo-<br />

Dadaism, Neo-Constructivism and Arte<br />

povera. Beyond its works in its own time,<br />

it has once more been linked with an era.<br />

However, it is important to recognise that<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> was one of those artists<br />

who transcend historical interest and<br />

survive beyond their own time through<br />

sheer intrinsic quality.<br />

Dr Elmer Belt,<br />

Photograph of <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> in Norway, 1939<br />

© Tate, London 2015

t<br />

46<br />

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE<br />

AND WORK OF<br />

KURT<br />

SCHWITTERS<br />

SIEGFRIED GOHR (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, Photograph of <strong>Kurt</strong> und Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>, ca. 1919<br />

© bpk / Sprengel Museum Hannover / Michael Herling / Aline Gwose

47<br />

t

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF KURT SCHWITTERS · by Siegfried Gohr<br />

t<br />

48<br />

•<br />

When the Dada movement arose in Zurich, Berlin and Cologne in 1916,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong> was still a member of the avant-garde. After a traditional training<br />

in painting in Dresden he had returned to his hometown of Hanover. Within this<br />

context his work enjoyed a certain recognition, but the First World War broke out<br />

and, despite his epilepsy, <strong>Schwitters</strong> was conscripted in 1917 as a draughtsman.<br />

Already during his Dresden period he had a relationship with Helma Fischer, whom<br />

he married in 1915. In 1918 their son, Ernst, was born.<br />

•<br />

After his initial experience with modern art in Hanover, it was only through<br />

Herwarth Walden’s gallery, Der Sturm, in Berlin that he made the decisive contact<br />

with the avant-garde. There, after the war, <strong>Schwitters</strong> saw works by Marc Chagall,<br />

Wassily Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger and Paul Klee. Walden had a feel for the talents<br />

of the young man from Hanover who painted in an idiom of expressionism, futurism<br />

and cubism. <strong>Schwitters</strong> remained in Hanover at Waldhausenstr. 5, where his family<br />

lived under the same roof with his parents. In the years 1918/19, <strong>Schwitters</strong> broke<br />

with his previous styles and began to glue and assemble collages and material<br />

images. The first <strong>Merz</strong>bild came about, which contained the meaningless fragment<br />

of a word, MERZ, that was cut out from the company name, COMMERZBANK. The<br />

world war had resulted in Germany as the loser which, however, also opened up<br />

new opportunities, because the Kaiser had fled to the Netherlands. However, the<br />

post-war period also brought with it upheaval, revolution, violence and insecurity<br />

in every respect. <strong>Schwitters</strong> felt the situation for himself as liberating. The war’s end<br />

coincided with the discovery of his own path. He flung himself into activities of all<br />

kinds: artist, advertising graphic artist, lecturer, poet, writer, organizer, publisher.<br />

•<br />

Whereas after the First World War, Dada artists moved toward Surrealism,<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> remained true to his own <strong>Merz</strong> cosmos. “<strong>Merz</strong> and Dada are related<br />

to each other through opposition,” he wrote. Nevertheless he was constantly put<br />

into a relation with Dada, although he did not want to belong to either this or any<br />

other group of artists. He had a particular dislike for the politically oriented Berlin<br />

Dadaism under the self-proclaimed leadership of Richard Huelsenbeck. Despite the<br />

differences, it nevertheless remains sensible to locate <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ art in a proximity<br />

to Dada. His personality had a structure suiting Dada before he was able to get to<br />

know Dada at all; he was a Dadaist by nature.<br />

•<br />

To establish his artistic cosmos, <strong>Schwitters</strong> employed two innovations that had<br />

become significant in the cubism of Picasso and Georges Braque: the collage and

49<br />

t<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

Hanover 1927<br />

the material image. What came about through his hands, however, was far removed<br />

from Parisian works because <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ preferred material was waste consisting<br />

of scraps of paper that he collected somewhere or other, and bits of objects he<br />

found. He carefully cleaned both, preserving the material in his sheer inexhaustible<br />

store until the right opportunity came along. Picasso, Braque, Juan Gris, among<br />

many others, used much more ‘noble’ materials for their collages. Mostly they<br />

came from the world of the café. Newspaper headlines, names of drinks, concert<br />

announcements and similar crop up, that is, fragments from the close milieu of Parisian<br />

bohemian life. Particularly Picasso found many a witty constellation, e.g. allusions<br />

to the fairer sex with double entendre, but political, social or historical elements are<br />

lacking. The cubists remained strongly committed to their abstract, stylistic research.<br />

By comparison, <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ collages possess a downright realistic character. The<br />

natural Dadaist element resided in <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ method of combining everything with<br />

everything, of admitting and balancing opposites. Something banal could become<br />

the most significant element, and conversely. <strong>Merz</strong> took in each and every thing,<br />

ultimately, perhaps the entire world. What found its way into his compositions was<br />

‘revalued’ by <strong>Schwitters</strong>, i.e. it partially lost its identity and became part of an artistic<br />

composition. <strong>Merz</strong> was a ferment that could permeate anything at all: advertising,<br />

the theatrical stage, a fantastic architecture such as the <strong>Merz</strong>bau, or literature.<br />

•<br />

In 1919 the publishing house of Paul Steegemann in Hanover published Anna<br />

Blume, in which the most famous poem by <strong>Schwitters</strong> appeared for the first time. Next

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF KURT SCHWITTERS · by Siegfried Gohr<br />

t<br />

50<br />

to the artist, the poet and man of letters, <strong>Schwitters</strong>, stepped onto the public stage.<br />

The echo was mixed, as was to be expected at the time. Despite the lifelong negative,<br />

hostile and deprecatory reactions to his art, <strong>Schwitters</strong> did not allow himself to be<br />

deterred, insisting on his <strong>Merz</strong> method, apparently unshaken. During the 1920s,<br />

despite all resistance, he became well-known and admired, but was also ridiculed and<br />

insulted. The acme of his activities was the ‘Dada campaign’ through the Netherlands<br />

in 1922/23. His restless activity led <strong>Schwitters</strong> to found the <strong>Merz</strong> publishing house.<br />

He published literary works such as Auguste Bolte elsewhere. A total of 21 <strong>Merz</strong><br />

periodicals appeared in his publishing house between 1923 and 1932, when the<br />

Ursonate appeared in Jan Tschichold’s typography. <strong>Schwitters</strong> earned his living also as<br />

an advertising graphic artist, e.g. for the Pelikan works in Hanover and the Dammerstock<br />

settlement in Karlsruhe. These works show the temporary influence of Dutch<br />

and Russian constructivism. In the Netherlands in 1917, the association of artists,<br />

De Stijl, had been founded under the theoretical leadership of Theo van Doesburg.<br />

During the 1920s, <strong>Schwitters</strong> sought contact. <strong>Schwitters</strong> approached the austere,<br />

sparing art of the Dutch, which comprised also architecture and everyday design. Of<br />

course, he was not at all inclined to bend to any kind of aesthetic dogma; therefore<br />

his ‘constructivism’ remains individual, and he always holds in store surprising turns<br />

and details. Apart from that, <strong>Schwitters</strong> combined colours very idiosyncratically, far<br />

removed from colleagues such as Piet Mondrian or Bart van der Leck. Apart from<br />

trips, lectures, correspondence, contacts, there remained in the background as a<br />

constant his work on the <strong>Merz</strong>bau, whose initial traces lead back to the year 1923;<br />

a ‘column’ had arisen. Ultimately, the architecture, the grottoes, the concentrations<br />

of material proliferated throughout the house at Waldhausenstr. 5 so that in the end,<br />

eight rooms and even a platform for sunbathing on the roof had come about. In<br />

1943, the building, including the <strong>Merz</strong>bau, was destroyed by an incendiary bomb.<br />

Three further <strong>Merz</strong>bau which <strong>Schwitters</strong> erected during exile in Norway and Britain<br />

were destroyed or have decayed. Of the centre of what he viewed as his life’s work,<br />

tragically, apart from a few fragments, nothing has remained.<br />

•<br />

Although <strong>Schwitters</strong> had had several stays in Norway starting in 1929, he did<br />

not consider emigrating. However, when he received news in 1939 that the Gestapo<br />

was looking for him, it became inconceivable for him to return to Hanover. After Hitler’s<br />

takeover of power in 1933, the avant-garde in Germany had a difficult time. All<br />

the compulsory measures taken against modern artists and their works reached<br />

their crescendo with the project, Degenerate Art, which resulted in the defamatory<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Merz</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, Auguste Bolte, Verlag Der Sturm, Berlin 1923

51<br />

t

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF KURT SCHWITTERS · by Siegfried Gohr<br />

t<br />

52<br />

exhibition in 1937 at the Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich<br />

that subsequently toured throughout Germany. <strong>Schwitters</strong> soon became aware that<br />

his career in Germany was at an end. Already before he finally went into exile in<br />

Norway in 1937, he had frequently spent time there. Germany and the other countries<br />

of his earlier activities, such as the Netherlands and Switzerland, offered scarcely any<br />

opportunities for having any resonance for his work. Helma <strong>Schwitters</strong> remained in<br />

Hanover, looking after the house. What had caused consternation among visitors to<br />

his exhibition in Hildesheim already in 1922 — namely, that <strong>Schwitters</strong> was working<br />

simultaneously both realistically and on <strong>Merz</strong> — became a vital necessity for him in<br />

order to earn some income. He did some portrait-painting, and offered his landscapes<br />

to tourists in Norway, however, with only moderate success. Realistic work represents<br />

a significant portion of his entire oeuvre which raises it above the status of mere<br />

bread-and-butter work. Orientation in Norway, of course, was difficult, and even<br />

a continuation of his artistic path was unclear. Collages came about continually; in<br />

1938/39 <strong>Schwitters</strong> attempted an abstract style, a mixture of ‘impressionist’ dabs<br />

of colour and flowing forms, but also nourished by recollections of his constructivist<br />

works after 1923. However, he returned to the material image into which organic<br />

found pieces such as algae, mussels, bark, etc. increasingly found their way.<br />

•<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> incorporated everything into his work that defined his life-world.<br />

Although he had nothing to do with traditional historical painting, the history of his<br />

own period was in his work, whether it be in the form of paper snippets, bus tickets,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

Norway 1933<br />

advertising, place names, wood, plaster, metal, wheels, bits of nature, and a lot more<br />

besides. His <strong>Merz</strong> periodicals as well were a mirror of the artistic strivings during the<br />

Weimar Republic. Therefore it amounts to a crude misappraisal to contemptuously

53<br />

look down upon the apparent nonsense in his works and poems; it reflects the errings<br />

and confusions of an entire period. The collision of work and reality, however, does<br />

not end negatively, but in a very idiosyncratic, new interpretation of what art could<br />

still be at all under the given historical conditions.<br />

t<br />

•<br />

For three years he lived with constant worries about a work permit and<br />

livelihood. After the German army invaded, he had to flee, which he succeeded in<br />

doing in dramatic circumstances, to Scotland. He boarded the last ship to depart<br />

Norway, the ice-breaker Fritjof Nansen. After various stages he was interred in a<br />

camp on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea from which he was released only in 1941,<br />

once again in exile in a foreign country. Just as little as in Norway were there<br />

any prospects of artistic success and recognition. Initially <strong>Schwitters</strong> remained in<br />

London where, as previously, he continued to collect the discarded remainders of<br />

civilization, ‘deformulating’ them and transforming them into <strong>Merz</strong> art. His works no<br />

longer had the constructivist background as in the 1920s, or the affinity to nature as<br />

in Norway. He increasingly selected a large urban iconography. Over everything,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

(looking at a<br />

daisy?), undated<br />

© Tate, London<br />

2015

INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF KURT SCHWITTERS · by Siegfried Gohr<br />

t<br />

54<br />

however, hung anxiety about the war and the aerial attacks. <strong>Schwitters</strong> therefore<br />

moved to the Lake District where nature received him hospitably. Landscapes and<br />

floral pieces came about besides portraits, collages and material images. Here his<br />

almost romantic inclination toward nature became apparent which hitherto had not<br />

played any decisive role in his oeuvre.<br />

•<br />

The only exhibition that took place in Britain during his lifetime was in 1944.<br />

It included more than 30 new works and, despite an essay by Herbert Read, an<br />

important art historian and critic, there was no sustained resonance. <strong>Schwitters</strong> the<br />

artist practically had ceased to exist in the public arena since the 1930s. In the<br />

United States there were individual attempts to arouse interest which, however, only<br />

bore fruit after the war. Although his health worsened progressively due to cardiac<br />

asthma, a stroke and eyesight problems that severely impaired his life, <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

created new works. Particularly touching are those works in which autobiographical<br />

motifs are legible. A collage from 1947 bears the title, A Finished Poet. Although the<br />

English romantic poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, is to be seen in a portrait from 1819, the<br />

parallel to <strong>Schwitters</strong> is obvious. Shelley, too, was forced by English society to leave<br />

the country. He died in Italy. Despite all the demonstrative persistence, <strong>Schwitters</strong> was<br />

all too aware of his tragic situation. There were phases of despair and depression;<br />

only contacts with the outer world were able to tear him out of the lethargic mood that<br />

continually recurred. Happily, with Edith Thomas, whom he called Wantee, in 1941<br />

he had found a person who lovingly took care of him. He experienced Wantee’s<br />

care as that of an angel whom his wife, Helma, had sent him. When he received<br />

the telegram in 1944 with news that Helma had died of cancer, <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ past in<br />

Hanover disappeared once and for all.<br />

•<br />

The generation of artists who were reorienting<br />

themselves since the late 1950s took up very<br />

different impulses from <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ oeuvre, for<br />

post-war abstraction had exhausted itself, and the<br />

gesture of the artist who captured psychic and<br />

physical energies on the canvas had rigidified. The<br />

rediscovery of Dada gained stimuli mainly from New<br />

York where the artist, Robert Motherwell, edited an<br />

anthology in 1951, The Dada Painters and Poets.<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, 1940s

55<br />

t<br />

Ernst <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>,<br />

Norway 1933<br />

•<br />

The book’s fourth chapter is devoted to <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ <strong>Merz</strong> art. On the one hand,<br />

the collage was re-established as an art form during the 1950s; on the other, the<br />

relationship between the art work and reality changed not only via this path. The art<br />

was to be short-circuited with the world, an aim which <strong>Schwitters</strong> had anticipated<br />

with his comprehensive <strong>Merz</strong> concept. In contrast to Marcel Duchamp, <strong>Schwitters</strong><br />

remained a realist throughout his life if by this concept is meant an open, inquisitive<br />

stance toward historical reality. Realism understood primarily as a stance and not<br />

as a style — that was <strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>’ cause. Duchamp’s search for the spirit of<br />

art, his irony, his periods of ‘silence’ and his dandyism were on another planet of<br />

modern art that orbited about itself. What the young American artists were able to<br />

take up from <strong>Schwitters</strong> was not limited to collage technique, for it had been used by<br />

many predecessors. What counted was the relation to the present itself in works that<br />

were apparently eccentric. <strong>Schwitters</strong> had employed advertising and public-domain<br />

images; he had wandered through his life-world with an open eye and had collected<br />

what seemed suitable to him. Even then he was a realist when he was not painting<br />

realistically, for which reason the apparent contradiction in the blocks of works is<br />

ameliorated. Not the technique, but the attitude was the message.<br />

•<br />

Much too late in life did his artistic work begin to be regarded for what it was:<br />

an epoch-making contribution to modern art, albeit a highly individual one by a loner.

t<br />

56<br />

The consequence of DADA:<br />

To Anna Blume<br />

MERZ<br />

Adrian Notz (<strong>2016</strong>)<br />

<strong>Merz</strong> theory:<br />

t t t<br />

Use of all kind of material for artistic work<br />

Playing off these materials against each other<br />

Imperative claim to autonomy for art (pure art) 1<br />

<strong>Kurt</strong> <strong>Schwitters</strong>, Die Blume Anna. Die neue Anna Blume. Eine Gedichtsammlung aus den Jahren 1918-1922,<br />

Der Sturm Verlag, Berlin 1923

t<br />

57<br />

t<br />

The beginning of <strong>Merz</strong> theory can be traced back to the origin of the so-called <strong>Merz</strong>bild<br />

of 1919, a collage on which <strong>Schwitters</strong> glued, between abstract shapes, the word MERZ that<br />

he had cut out of an advertisement of the KOMMERZ and PRIVATBANK 2 . This is where<br />

<strong>Schwitters</strong> came upon the word <strong>Merz</strong>. At the beginning of the evolution of <strong>Merz</strong> as a theory,<br />

though, there is a woman: Anna Blume. It<br />

is her who stimulates <strong>Merz</strong> and in the first<br />

<strong>Merz</strong>gedicht (<strong>Merz</strong>poem), she stands at<br />

the beginning of an evolution. The great<br />

yearning and wonderfully playful, tender<br />

declaration of love, that the “I” in An<br />

Anna Blume (To Anna Blume) professes,<br />

is already dissolved a few pages later in<br />

the 8 th <strong>Merz</strong>gedicht, in an execution of<br />

oneself. One realizes that Anna Blume<br />

will never be reached, as she merely is<br />

an illusion, a creation that stems from<br />

the longing imagination of the “I”. This<br />

realization, that a fictitious entity is able to<br />

create a real yearning, triggers an equally<br />

real self-dissolution, which finds its poetic<br />