Catholics Changing God's Name .pdf File - to see how to be born ...

Catholics Changing God's Name .pdf File - to see how to be born ...

Catholics Changing God's Name .pdf File - to see how to be born ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

CATHOLICS<br />

CHANGING<br />

GOD’S NAME<br />

1<br />

G.A. RIPLINGER

THE HOLY BIBLE says, “and his name is called The Word of God”<br />

Or in Spanish this would say,<br />

“y su nombre es llamado la Palabra de Dios.” (Rev. 19:13).<br />

Or is it,<br />

“y su nombre es llamado el Verbo de Dios.”<br />

S<br />

Sparring over synonyms in translation can <strong>be</strong> difficult. Is the child pretty,<br />

lovely, attractive, or <strong>be</strong>autiful? A case, giving particulars, must <strong>be</strong> made for<br />

each word. But changing the pretty child’s name from Pamela <strong>to</strong> Verna is<br />

something that is not up for debate. Yet modern Spanish Bibles have done just that,<br />

changing the “name” that Jesus Christ “is called.” This “ought not <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> done.”<br />

How did this happen? Wouldn’t you know that Pope Novatian changed it in a<br />

tract and later Jerome arranged its place in the Latin Bible. This article will document<br />

this, citing Latin and Greek scholars who publish in juried professional journals. Now<br />

there are piles, which stretch for miles, of moth eaten Latin manuscripts and bibles<br />

stained with this name.<br />

2

JOHN 1:1<br />

in the<br />

SPANISH BIBLE:<br />

��<br />

A Comprehensive His<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

of the Latin/Spanish Words<br />

for<br />

‘Word’<br />

Sermo/Palabra<br />

VS.<br />

Verbum/Verbo<br />

������<br />

“In the <strong>be</strong>ginning was the Word,<br />

and the Word was with God,<br />

and the Word was God.”<br />

3

The Catholic Latin Vulgate’s Introduction of Verbum in the 4 th century<br />

VS<br />

The Old Latin word Sermo, as used in the Old Pure Latin Text & By Erasmus<br />

T<br />

he original Latin Bible is at the root of other later vernacular Bibles, such as<br />

the Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese Bibles. These later languages<br />

developed just <strong>be</strong>fore the turn of the millennium (c. 900). Their Holy Bible, which<br />

branched off of the pure Old Latin, came along immediately. These languages and their<br />

Bibles carry the original Latin words on <strong>to</strong> <strong>to</strong>day. Therefore, it is easy <strong>to</strong> determine which<br />

Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese versions come directly from the original pure<br />

Latin text, rooted in Acts 2. It also <strong>be</strong>comes clear which editions are rooted in or have<br />

<strong>be</strong>en tainted by the fourth century Latin corruption of the Roman Catholic, Jerome, who<br />

copied Verbum from its origina<strong>to</strong>r Pope Novatian (See upcoming documentation and G.A. Riplinger, In Awe<br />

of Thy Word, Ararat, VA: A.V. Publications, 2003, pp 982-988 (French and Spanish) and pp. 962-968 (Old Latin, Itala VS Jerome’s<br />

Vulgate).<br />

For example, the Word, Jesus Christ, in John 1:1 was rendered in the Old Latin as<br />

Sermo, until Jerome changed it <strong>to</strong> Verbum in the fourth century (See G.A. Riplinger, Hazardous<br />

Materials, Ararat, VA: A.V. Publications, 2009, p. 1123). Pure Romance language Bibles, deriving from the<br />

Latin, did not use the word Verbo. Instead they followed the original Old Latin. The<br />

French Ostervald said Parole, the LeFevre’s French said parolle, Olivetan’s French said<br />

parolle, the Geneva French said Parole, the Italian Diodati said Parola, and the Swiss<br />

version said Parole. The Indo-Portuguese says Palavra, Almeida’s Portuguese says<br />

palavra, the Toulouse says paraoulo, the Vaudois says Parola, the Piedmontese says<br />

Parola, and the Romanese says Pled. Likewise, the word Palabra has <strong>be</strong>en used in the<br />

Spanish Bible from the earliest days, including the Valera 1602 and the Reina 1569. Even<br />

Strong admits that “For the greater part he [Enzinas] follows Erasmus’s translation, e.g.<br />

John i,1: En el principio era la palabra, y la palabra estava con Dios, y Dios era la<br />

palabra” (McClin<strong>to</strong>ck and Strong, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature, Baker Book House, 1981 reprint, vol. 9, p. 99; See<br />

The Bible of Every Land, 2 nd edition, London, 1860 under each language, pp. 251-288). No pure vernacular translation<br />

has used Jerome’s unique Catholic rendering, Verbum. (See Appendix A for<br />

documentation that Verbo is rejected by Protestants.)<br />

Jerome’s corruption was introduced in<strong>to</strong> the Spanish Bible in 1793 by Roman<br />

Catholic Padre [‘Father’] Scio, who translated from Jerome’s corrupt Vulgate (The Bible of<br />

Every Land, p. 266). Just as the 1611 KJB reigned supreme for 270 years, until the 1881<br />

Revised Version, so the word Palabra reigned from the Enzinas Spanish edition of 1543,<br />

for 250 years, until Father Scio changed it along with scores of other words. Enzinas in<br />

1543, Pineda in 1556, Reina in 1569, and Valera in 1602 all continued using the word<br />

Palabra.<br />

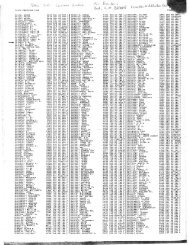

As the following chart s<strong>how</strong>s, <strong>to</strong>day the text of the Spanish 1602 Purificada alone<br />

retains the pure reading; modern Spanish versions bring forward Father Scio’s corruption.<br />

Therefore the word Verbo can <strong>be</strong> <strong>see</strong>n in some modern Spanish Bibles, such as the 1960,<br />

Trinitarian Bible Society, Gómez, La Biblia de las Américas, La Nueva Biblia de las<br />

Hispanos, and the 1865.<br />

4

Spanish Editions<br />

1543 Enzinas palabra<br />

1556 Pineda Palabra<br />

1569 Reina (Spanish) Palabra<br />

1602 Valera Palabra<br />

1602 Valera Purificada Palabra<br />

1793 Catholic Padre Scio Verbo<br />

1823 Catholic Bishop Amat Verbo<br />

1865 Verbo<br />

Gómez Verbo<br />

1960 Verbo<br />

Word (John 1:1 et al.)<br />

Scio’s Spanish of 1793 was printed as a parallel Latin Vulgate and Spanish Bible.<br />

The following are scans from the His<strong>to</strong>rical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of Holy<br />

Scripture by T.H. Darlow and H.F. Moule (London: The British and Foreign Bible<br />

Society, 1903-1911, Cambridge, MA: Maurizio Martino-Publisher Reprint, Vol. II, 3, pp.<br />

1438, 1439). It gives the actual title of Scio’s monstrous new ‘revised version’ as, The<br />

Latin Vulgate Bible Translated in<strong>to</strong> Spanish, and noted conforming <strong>to</strong> the meaning of<br />

the holy Fathers [Popes] and Catholic exposi<strong>to</strong>rs by the Father Philip Scio of San<br />

Miguel.<br />

As Darlow and Moule’s following description states, the Spanish was “Translated<br />

from the Latin Vulgate,” “The Spanish and Latin texts are given in parallel columns…”<br />

and “Jerome’s translation” was even included in subsequent editions.<br />

5

T<br />

He Holy Bible is the ‘word’ of God, using the ‘words’ of God, <strong>to</strong> represent Jesus<br />

Christ, the Word of God. If a Bible, which claims <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> the ‘word’ of God, was done<br />

by a transla<strong>to</strong>r who does not know <strong>how</strong> <strong>to</strong> translate the basic word ‘Word,’ then all of<br />

their other word choices are put in serious doubt. The use of identical words, connecting<br />

the written word and the living Word, Jesus Christ, are crucial (John 1:1). All foreign<br />

Bibles have identical words for Jesus, the Word, and the written ‘word.’ For example,<br />

when comparing the words in John 1:1 and 1 Peter 3:1, we find the same words, such as<br />

Word/word in English, Parole/parole in French, Parola/parola in Italian, Woord/woord<br />

in Dutch, Sana/sana in Finnish, and Wort/wort in German. (See Appendix at end.) The<br />

Valera 1602 Purificada has Palabra/palabra. The corrupt readings cited in the chart<br />

instead say Verbo/palabra, breaking a vital cross-reference and theological connection.<br />

Assertions by li<strong>be</strong>rals that Jesus is the spoken word, but not the written word (and<br />

therefore these ‘words’ should <strong>be</strong> translated as different words) ignore the myriad of<br />

verses which parallel the written word (scriptures) and Jesus Christ. Jesus said, “It is<br />

written…”, elevating the written word, even above himself. The written word is even<br />

magnified above his name (Word), according <strong>to</strong> Psalms 138:2 which says, “for thou hast<br />

magnified thy word above all thy name.” The idea that Jesus is only the spoken word is<br />

rift in li<strong>be</strong>ral textbooks and lexicons, which all <strong>see</strong>k <strong>to</strong> deny the parallel perfection of the<br />

written word and Christ, the Word. The Bible’s built-in dictionary parallels Jesus, the<br />

Word, with the “written” word. It says, “the word of God, and of the testimony of Jesus<br />

Christ…he that readeth, and they that hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those<br />

things which are written therein…I am Alpha and Omega…write in a book…” (Rev. 1:1-<br />

11). The use of two dissimilar words looses the connection <strong>be</strong>tween the Word <strong>be</strong>coming<br />

flesh (tangible, like the written word). They also miss the connection <strong>be</strong>tween the bodily<br />

resurrection of Jesus Christ and the resurrection and preservation of the tangible written<br />

words of God. Separating the two words and translating them differently smacks of Barth<br />

and Brunner’s neo-orthodox ideas about the Word and the word, wherein the written<br />

word is some<strong>how</strong> less than the actual spirit of his mouth, which is, in a sense, a part of<br />

him (2 Thes. 2:8, Eph. 6:17, Rev. 1:16, 2:16, 19:15, 21). The “engrafted” word, like Jesus<br />

the Word, is “able <strong>to</strong> save your souls.”<br />

False assertions that the masculine word Verbo is preferable <strong>to</strong> the feminine<br />

Palabra are not Biblical. Jesus is descri<strong>be</strong>d using feminine Spanish nouns such as the<br />

door (la puerta), the vine (la vid), the light (la luz), and the truth (la verdad). As this<br />

paper documents, all pure Romance language Bibles, including the French, Italian,<br />

Romant, Toulouse, Vaudois, Swiss, and Piedmontese, throughout all of his<strong>to</strong>ry, have<br />

included the word ‘la’ <strong>be</strong>fore their proper name for ‘Word’, in spite of the fact that such<br />

usage is not typical in any of these languages. Jesus, the Word, is hardly typical. Those<br />

who insist that la Palabra is wrong <strong>be</strong>cause of its gender are denying God’s preserving<br />

work and vilifying every Holy Bible he has given throughout his<strong>to</strong>ry! See Appendix A.<br />

A His<strong>to</strong>ry of the Words<br />

The scholarly treatise on the his<strong>to</strong>ry of the Bible, The Bible of Every Land, gives<br />

the rendering of John chapter one in every ancient and living language that is available. It<br />

s<strong>how</strong>s that the ancient Latin texts of Erasmus, as well as Castalio, used the word Sermo<br />

(The Bible of Every Land: A His<strong>to</strong>ry of the Sacred Scriptures in Every Language and Dialect In<strong>to</strong> Which Translations Have Been<br />

Made, London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1860, pp. 251-253).<br />

6

“The version of Castalio or Chatillon was printed at Basle in 1551, with a<br />

dedication <strong>to</strong> Edward VI, king of England. It was reprinted at Basle in<br />

1573, and at Leipsic in 1738. The design of Castalio was <strong>to</strong> produce a<br />

Latin translation of both Testaments in the pure classical language of the<br />

ancient Latin writers” (Emphasis mine; The word ‘ancient’ generally refers <strong>to</strong> the period <strong>be</strong>fore<br />

A.D. 300; The Bible of Every Land, p. 251).<br />

The pure Latin text that I use continually, when looking for the most ancient Latin<br />

reading, is the Old Latin text of the reformer Beza. He had the ancient manuscript,<br />

CODEX CANTABRIGIENSIS, which contains both a Greek and a Latin text from the fifth<br />

century. Although it is missing in this area of discussion and some other verses, it is an<br />

excellent source of the true Old Latin text. In John 1:1 Beza writes,<br />

“In principio erat Sermo ille, et<br />

Sermo ille erat apud Deum,<br />

eratque ille Sermo Deus. Hic<br />

Sermo erat in principio apud<br />

Deum. Omnia per hunc<br />

Sermonem facta sunt, et<br />

absque eo factum est nihil quod<br />

factum sit.” (John 1:1-3). (Jesu<br />

Christi Domini Nostri Novum Testamentum.<br />

Ex Interpretatione Theodori Bezae Impressa<br />

Cantabrigiae A.D. 1642 in Officina Rogeri<br />

Danielis. Londini: Sumptibus Societatis<br />

Bibliophilorum Britannicae et Externae.<br />

MCMLXV, p. 203).<br />

7

All Scholars Say ‘Verbum’ Is Not the Original<br />

Erasmus wrote a complete treatise against the use of the word Verbum in John<br />

1:1. This treatise is available as Lugduni Batavorum, in the Leiden edition of the works of<br />

Erasmus, edited by Leclerc, 1703, reprinted 1963. (See the Apologia for Sermo, LB IX, 111-22, 446, and<br />

annotations on John 1:1).<br />

In Awe of Thy Word traces Erasmus’ development, from his forced childhood<br />

immersion in<strong>to</strong> the Catholic church, <strong>to</strong> his break with them and their false Latin Vulgate.<br />

His editions of the Latin Bible s<strong>how</strong> that development, as his first edition (1516) copied<br />

the Vulgate word Verbum, which he had <strong>see</strong>n all his life, while held captive by Catholic<br />

monks. His second and subsequent editions of the Bible use the word Sermo in John 1:1,<br />

demonstrating his growth and exposure <strong>to</strong> a wider and purer range of manuscripts, once<br />

he separated himself from the Catholic church and <strong>be</strong>gan associating with the reformers.<br />

In fact, he felt so strongly about the word Sermo that he wrote an entire treatise<br />

AGAINST the word Verbum.<br />

The KJB transla<strong>to</strong>rs did not follow Erasmus’s first edition, but his later, more<br />

matured edition. Luther did not follow Erasmus’ first edition either, but his second<br />

edition. Tyndale, as well, did not follow Erasmus’ first edition, but his later editions.<br />

Consequently, references <strong>to</strong> Erasmus’ first edition <strong>to</strong> support error, which Erasmus<br />

himself quickly corrected, is without sound reason. Given the lengthy domination of the<br />

Catholic church over Spain, all Spanish-speaking countries, and all of their universities, it<br />

is not surprising <strong>to</strong> find the word ‘verbum’ from their Latin Vulgate, included in<br />

reference works and dictionaries, thereby supporting their Latin Vulgate text, which<br />

follows Jerome.<br />

Contemporary his<strong>to</strong>rians have rehearsed Erasmus’ treatise in scholarly journals.<br />

M. O. Boyle wrote several articles. These include Sermo: Reopening the Conversation on<br />

Translating JN 1:1. It was published by Brill in Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 31, No. 3,<br />

Sept., 1977, pp. 161-168. It is currently available from http://www.js<strong>to</strong>r.org/stable/1583129.<br />

When summarizing the article by Boyle, the following facts will <strong>be</strong> drawn from<br />

the article:<br />

1.) The earliest Latin manuscripts and Christian writers (c. 160-260) do not use the<br />

word Verbum, but Sermo in John 1:1.<br />

2.) The word Verbum was originally introduced by Pope Novatian in a pamphlet.<br />

(There were two competing Popes at this time. He and his followers differed from<br />

the rival Pope in that Pope Novatian did not <strong>be</strong>lieve that those who had committed<br />

8

sacrilege could ever <strong>be</strong> forgiven and res<strong>to</strong>red <strong>to</strong> Catholic communion. Real<br />

Christians, of which there were plenty, would not even want ‘Catholic’<br />

communion, which <strong>Catholics</strong> <strong>be</strong>lieve is the actual flesh of Jesus Christ. Real<br />

Christians would welcome anyone who had repented. Novatian re-baptized<br />

people, just like the “Church of Christ.” His actual <strong>be</strong>liefs, whether bad or good,<br />

do not negate the his<strong>to</strong>rical fact that he introduced the word ‘verbum’ well after<br />

the word sermo had <strong>be</strong>en recorded in scripture citations by Tertullian, who said<br />

“The blood of the martyrs is the <strong>see</strong>d of the church.”)<br />

3.) The word verbum was later cast in<strong>to</strong> the text of the Catholic Bible by Jerome in<br />

his revised Latin Vulgate. Even Jerome admits, “You [Pope Damasus] urge me <strong>to</strong><br />

revise the Old Latin, and, as it were, <strong>to</strong> sit in judgment on the copies of Scripture<br />

which are now scattered throughout the world…Is there not a man, learned or<br />

unlearned, who will not, when he takes the volume in hand…call me a forger and<br />

a profane person for having had the audacity <strong>to</strong> add anything <strong>to</strong> the ancient books,<br />

or <strong>to</strong> make changes…” (See Wordsworth and White, Novum Testamentum...Latine, vol. I, pp. 1-4 or any<br />

critical edition of the corrupt Latin Vulgate.) When his corrupt Vulgate was complete, Jerome<br />

admitted that Christians “have pronounced <strong>to</strong> have branded me a falsifier and a<br />

corrupter of the Sacred Scriptures” (Lit. “qui me flasarium corrup<strong>to</strong>remque sacrarum pronunciant<br />

Scripturarum” (See In Awe p. 963 et al.).<br />

4.) Trusted Reformation linguists, such as Erasmus and Theodore Beza, soundly<br />

rejected the word Verbum, in both their Latin texts and in their essays.<br />

5.) Modern scholars (classicists, that is, those who teach at the university level and<br />

publish research about the classical languages, such as Latin and Greek) recognize<br />

that the word Verbum is of later and of Catholic origin. They observe that verbum<br />

is not a correct rendering of the Greek word logos and is, in fact, the opposite of<br />

logos.<br />

In dry, scholarly, and pseudo-spiritual drone, Boyle says, for example:<br />

“From Tertullian [c. 150 – c. 230 A.D] <strong>to</strong> Theodore de Beze<br />

extends a tradition of translating λόγος [logos] in John 1, 1 as sermo, a<br />

tradition now forgotten even by cura<strong>to</strong>rs of antique words. Only when<br />

Erasmus res<strong>to</strong>red the variant in his second edition of the New Testament<br />

(1519), and defended it with a battery of philological and patristic<br />

arguments, did the translation incite public debate. [Boyle notes, “Erasmus,<br />

Annotationes in evangelium Joannis in Opera omnia 6 (Leiden 1703-1706) 335A-337C; Apologia de “In<br />

principio”, LB 9, 111B-122F. “Sermo”, the first chapter of my book Erasmus on Theological Method (Toron<strong>to</strong><br />

in press) is entirely devoted <strong>to</strong> documentation and analysis of this. I thank the University of Toron<strong>to</strong> Press for<br />

permission <strong>to</strong> rework this here.”] With the Tridentine sanction of the Vulgate’s<br />

verbum, <strong>how</strong>ever, the impetus for the tradition of sermo ceased. And<br />

although, fortified by Calvin’s commentary on John, Beze translated<br />

λόγος [logos] as sermo in his NT editions...”<br />

Boyle continues,<br />

9

“It [the debate against verbum] deserves <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> revived for scholarly<br />

examination. Sermo is the most ancient extant Latin translation for<br />

λόγος [logos] in the Johannine prologue. It conserves faith’s witness <strong>to</strong><br />

Christ the eloquent discourse of God, a witness his<strong>to</strong>rically diminished by<br />

the truth which the translation verbum served…Tertullian [A.D. 150-230]<br />

and Cyprian [A.D. 208-258] quote sermo in every citation of the opening<br />

verses of the Johannine prologue. In addition <strong>to</strong> eight quotations, there is<br />

Tertullian’s valuable, impartial testimony in Adversus Praxean that the<br />

cus<strong>to</strong>m of Latin Christians was <strong>to</strong> read In Principio erat sermo…Cyprian<br />

twice quotes John 1,1 in Adversus Iudaeos ad Quirinum as In principio<br />

fruit sermo, et sermo erat apud Deum, et Deus erat sermo. He also<br />

interprets sermo as Christ in three psalm verses and a passage from the<br />

Book of Revelation. Cyprian is acknowledged a superior source of the<br />

Old Latin Bible <strong>be</strong>cause of his antiquity and <strong>be</strong>cause he repeats almost<br />

one-ninth of the New Testament…Sermo remains then the earliest extant<br />

Latin translation of λόγος [logos] in John 1, 1 and on Tertullian’s word the<br />

reading commonly circulated.”<br />

Boyle goes on <strong>to</strong> say,<br />

“Verbum first occurs as a translation for λόγος [logos] in John 1, 1<br />

in Novatian’s tract on the Trinity, but he reports sermo also. [Pope<br />

Novatian, c. A.D. 200-258, held the title of “Pope” and “antipope,” since<br />

he held the position at the same time as Pope Cornelius,” according <strong>to</strong><br />

Wikipedia.] After Novatian this ambivalence about sermo and verbum<br />

disappears until Augustine revives it…By the fourth century verbum is<br />

universally preferred in the West…Isaac Judaeus, in his exposition on the<br />

catholic faith at about the same time, also quotes verbum in the<br />

prologue…Without leaving an explanation, he [Jerome] choses verbum, a<br />

decision which as<strong>to</strong>nished Erasmus [Erasmus, Apologia de “in principio erat sermo,”<br />

LB9, 113E.]…”<br />

Boyle concludes,<br />

“[S]ermo and verbum are not synonymous. They may even <strong>be</strong><br />

regarded as an<strong>to</strong>nyms [opposites]. Verbum may <strong>be</strong> argued a<br />

grammatically inaccurate, at least inappropriate, translation for λόγος<br />

[logos] in John 1, 1…Sermo…also refers <strong>to</strong> national <strong>to</strong>ngues…During the<br />

fourth century sermo <strong>be</strong>came the Christian term for preaching….In<br />

grammatical parlance, verbum is a verb. The Greek counterpart of<br />

verbum is not λόγος [logos] but λέξις, precisely a vocable that λόγος<br />

[logos] can never signify grammatically. Although from Jerome’s<br />

redaction until Erasmus’ the translation of λόγος [logos] in Jn 1, 1 came<br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> transmitted as verbum, Anselm of Canterbury, Remigius, Hugh of<br />

St. Cher, Nicolas of Lyra, Thomas Aquinas and the glossa ordinaria all<br />

interpret biblical occurances of sermo as Christ…”<br />

10

Boyle continues,<br />

“For Erasmus, editing the first Greek and Latin edition of the New<br />

Testament, this semantic indiscretion [verbum] of the early Church<br />

[Jerome] diminished its faithful testimony <strong>to</strong> Christ as the Father’s<br />

eloquent oration <strong>to</strong> men. “Sermo,” he argued “more perfectly explains why<br />

the evangelist wrote λόγος [logos], <strong>be</strong>cause among Latin-speaking men<br />

verbum does not express speech as a whole but one particular saying. But<br />

Christ is for this reason called λόγος [logos]: <strong>be</strong>cause whatsoever the<br />

Father speaks, he speaks through the Son.” [See Erasmus, Annotations in Evangelium<br />

Joannis LB 6, 335C; cf. 335A, B and Apologia de “in principio erat sermo” LB 9, 121D, 122D]<br />

“…verbum is inadequate <strong>to</strong> designate him. One can choose verbum…Or<br />

one can employ the grammatically correct sermo, rendering the Greek<br />

New Testament faithfully…”<br />

Boyle goes on <strong>to</strong> state that verbum is Pla<strong>to</strong>nic. This is not a good<br />

philosophical shadow <strong>to</strong> cast over Christ. (bold emphasis mine; Sermo: Reopening the<br />

Conversation on Translating JN 1:1. Published by Brill, in Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 31, No. 3, Sept., 1977,<br />

pp. 161-168). It is not the purpose of this short article <strong>to</strong> go in<strong>to</strong> the dangerous<br />

philosophical and theological ramifications of the use of the word<br />

‘Verbo’ for God. However, the perennially competing philosophies about<br />

the character of God (i.e. as a personal God VS the impersonal ‘Force’)<br />

meet in the debate <strong>be</strong>tween ‘Verbum/Verbo’ and ‘Sermo/Palabra. The<br />

former view is <strong>see</strong>n in the wicked occult book entitled, God is a Verb:<br />

Kabbalah and the Practice of Mystical Judaism by David Cooper. It is typical of the<br />

pantheistic New Age view that God is a force, like a verb. Of the ‘god of forces’ we are<br />

warned in the book of Daniel.<br />

In their writings, all non-Christian classicists, such as Boyle, mix true his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

facts, such as I have cited thus far, with their own Christless opinions. Such nonscriptural<br />

views, such as Boyle’s idea that Christ is the conversation and not the word,<br />

must <strong>be</strong> rejected. English is a Germanic language and as such cannot and should not <strong>be</strong><br />

impacted by non-contextual definitions in dictionaries by Latinists. While ignoring<br />

Boyle’s baseless opinions, the article’s his<strong>to</strong>rical facts are solidly corroborated by other<br />

scholars also.<br />

F<br />

following:<br />

urther contemporary scholarly evidence, demonstrating the introduction of<br />

the word verbum by <strong>Catholics</strong>, such as Jerome and Augustine, is <strong>see</strong>n in the<br />

1.) Roland H. Bain<strong>to</strong>n’s Erasmus of Christendom. Bain<strong>to</strong>n was for forty-two years<br />

Titus Street Professor of Ecclesiastical His<strong>to</strong>ry at Yale University. In his<br />

definitive Erasmus of Christendom he brought out the crucial debate Erasmus<br />

engaged in, as Erasmus denounced the word verbum in John 1. Bain<strong>to</strong>n writes,<br />

“The other rendering <strong>to</strong> create a stir was John 1:1, “In the <strong>be</strong>ginning was<br />

the Word.” The Vulgate rendering for “Word” was verbum. Beginning<br />

11

with the edition of 1519 Erasmus translated it as sermo. He was accused of<br />

complete innovation and suspected of demeaning the incarnation. He<br />

proved that he was no innova<strong>to</strong>r by citations from the Fathers, but<br />

regardless of the tradition, sermo, said he, is a <strong>be</strong>tter translation….In his<br />

treatise on the training of preachers Erasmus affirmed that the title sermo<br />

is <strong>be</strong>s<strong>to</strong>wed only on Christ. Men are sometimes called sons of God and<br />

even gods, but never the Word of God. Christ was the sermo” (Bain<strong>to</strong>n, pp. 140,<br />

149, 306).<br />

2.) The Cambridge His<strong>to</strong>ry of Literary Criticism: The Renaissance contains a<br />

complete analysis by M.O. Boyle of Erasmus’ castigation of Verbum (Vol. 3,<br />

1999, edited by Glyn P. Nor<strong>to</strong>n. See Cambridge His<strong>to</strong>ries Online. Cambridge<br />

University Press, 15 Septem<strong>be</strong>r 2010. See “Evangelism and Erasmus” by M. O.<br />

Boyle in Front matter).<br />

What is ‘Old Latin?’<br />

Comments, such as ‘all Latin manuscripts say,’ or ‘all Old Latin manuscripts say’ are<br />

without any academic basis for two reasons:<br />

1.) The approximately 10,000 Latin manuscripts are held generally at the Beuron<br />

Ancient Latin Institute (Vetus Latina Institut), which is a Catholic cloister,<br />

that is, a monastery from which no one who enters is ever permitted <strong>to</strong> leave.<br />

Those who have escaped such ‘cloisters’ have reported the heinous activities<br />

which they harbor. For this reason, there has never <strong>be</strong>en any published, non-<br />

Catholic, collation of all of the Latin manuscripts.<br />

2.) To Bible <strong>be</strong>lievers, the term ‘Old Latin’ refers <strong>to</strong> those true texts written<br />

BEFORE Jerome’s revision and used by true Christians from the first century<br />

until the Latin language was replaced by a variety of vernacular languages.<br />

Conversely, <strong>to</strong> modern li<strong>be</strong>ral scholars, ‘Old Latin’ is defined as those extant<br />

manuscripts which survive from <strong>be</strong>tween the 4th and the 12 th centuries.<br />

References <strong>to</strong> web sites which purport <strong>to</strong> represent the ‘Old Latin’, such as<br />

http://www.vetuslatina.org, will render piles of Catholic Vulgate texts, which,<br />

when stacked miles high, have hidden God’s word from the <strong>Catholics</strong> who<br />

lived in their shadow. I challenge those who use the term ‘Old Latin’ <strong>to</strong> defend<br />

the use of Verbo <strong>to</strong> include the actual dates of the manuscripts they are<br />

referring <strong>to</strong>. They will all <strong>be</strong> post-Jerome. Li<strong>be</strong>ral ‘scholars’ mis-define “Old<br />

Latin” manuscripts, as <strong>be</strong>ing those manuscripts from “<strong>be</strong>tween the fourth and<br />

twelfth centuries.” A web site which purports <strong>to</strong> represent the Old Latin texts<br />

says, “Since the Old Latin manuscripts were produced at many different<br />

times (<strong>be</strong>tween the fourth and twelfth centuries), in many locations and have<br />

different degrees of difficulty in their interpretation, we have had <strong>to</strong> vary the<br />

strict application of our transcription rules” (Vetus Latina Iohannes, Introduction, p. 1, par. 4,<br />

http://arts-it<strong>see</strong>.bham.ac.uk/it<strong>see</strong>web/iohannes/vetuslatina/index.html).<br />

They mis-define ‘Old Latin texts as <strong>be</strong>ing those made <strong>be</strong>tween the 4 th and the<br />

12 th centuries, <strong>be</strong>cause the true early Old Latin manuscripts from the first<br />

12

through the third centuries were destroyed, along with their owners, in the<br />

varied persecutions which <strong>to</strong>ok place during the first three centuries.<br />

Therefore, the Latin manuscripts which are still extant escaped destruction,<br />

<strong>be</strong>cause they were the property of the Catholic persecu<strong>to</strong>rs, who through the<br />

ensuing centuries destroyed Bibles which did not match their Vulgate! A<br />

perusal of web sites purporting <strong>to</strong> discuss ‘Old Latin’ manuscripts will <strong>be</strong><br />

found <strong>to</strong> house only manuscripts which were produced AFTER Jerome’s<br />

revision, that is, after the years 380-405 (e.g.http://www.vetuslatina.org). A<br />

tell-tale reminder that these internet manuscripts originated in Catholic<br />

monasteries is the use of illumination, that is, gilded artwork and ornate handlettering.<br />

These illuminated manuscripts were not the property of simple<br />

Christians, who read their hand-written Bible. They were the work of<br />

cloistered monks who rendered the artwork and ornately lettered the text. The<br />

spiritually bankrupt Catholic church has always relied upon the visual arts, in<br />

their manuscripts, cathedrals, and statuary, <strong>to</strong> appeal <strong>to</strong> the lusts of the eyes.<br />

Summary and Conclusions<br />

T<br />

his short essay demonstrated that the current use of the word ‘Verbo’ in modern<br />

Spanish versions has the following problems:<br />

1.) It is not a correct translation of the Greek word λόγος, as noted by Greek classicists,<br />

2.) It was not the original pure word from the Old Latin Bible, as demonstrated by the<br />

most ancient writers (e.g. Tertullian) and repeated by pure Reformation era scholars. The<br />

use of scripture verses by those living in the first three centuries has always <strong>be</strong>en used <strong>to</strong><br />

give us a view of what scriptures they had in-hand then. Such authors are used <strong>to</strong> DATE<br />

readings, since their scripture citations are in many cases the only witnesses we have for<br />

Old Latin Bibles which were destroyed by the persecu<strong>to</strong>rs. The theology of the writer<br />

does not annul the usefulness of their scripture citations.<br />

3.) It is not the rendering used in any other pure Romance language vernacular Bible,<br />

either currently or his<strong>to</strong>rically.<br />

Those who use Verbo must give in <strong>to</strong> the following errors:<br />

1.) They must reject the most widely accepted Latin Dictionary, that of William<br />

Whitaker, which gives definitions for sermo, which include “the word,” while<br />

calling verbum a “word” (http://archives.nd.edu/words.html). Jesus Christ is<br />

definitely “the word.” All dictionaries give several so-called meanings, not<br />

necessarily as synonyms of each other, but as meanings in different contexts. For<br />

example the word ‘save’ can mean ‘back up a computer,’ ‘put money in the<br />

bank,’ ‘a baseball term,’ or the theological definition ‘save from sin.’ The<br />

definitions cannot <strong>be</strong> mixed <strong>be</strong>tween contexts. Whitaker gives several definitions<br />

of ‘sermo’ and, as the precedence of the OED dictates, the theological definition<br />

(“the word”) is fourth, or so.<br />

2.) They must reject the use of the word Palabra by both Reina and Valera.<br />

3.) They must use the term ‘Old Latin’ without giving actual dates.<br />

13

4.) They must promote the acceptance of modern inventions in translation.<br />

5.) They must <strong>be</strong>lieve that God did not preserve his words in anything but Catholic<br />

Vulgate manuscripts and a Spanish Bible taken from them in 1793 by Father Scio,<br />

and followed by li<strong>be</strong>rals in the 1960 edition.<br />

6.) They must base their reading on the extant Vulgate manuscripts, which survived<br />

<strong>be</strong>cause they were the product of the persecu<strong>to</strong>rs, who destroyed Bibles which<br />

disagreed with theirs.<br />

7.) They must ignore the fact that the original 1865 Spanish Bible used “Palabra” for<br />

Word. It was changed in 1868, according <strong>to</strong> the American Bible Society, whose<br />

records state,<br />

“A point of interest in this connection is committee action in 1868 by<br />

which the word “Palabra” was ordered changed <strong>to</strong> “Verbo,” Dr. Schmidt<br />

<strong>to</strong> make a list of the places where this was <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> done. At the next meeting<br />

he reported changes <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> made in John 1:1, 14, 1 John 1:1, 5:7 and Rev.<br />

19:13 (V 5.4 and 9.28.1868) (ABS His<strong>to</strong>rical Essay #16, IV, Text and<br />

Translation, 1860-1900, D. European Languages, Margaret T. Hills,<br />

January, 1966).<br />

De Mora, now working with Gilman “further corrected” that edition in 1872 and<br />

1876 (ABS His<strong>to</strong>rical Essay #16, p. 5).<br />

The li<strong>be</strong>ral mindset of the American Bible Society from the mid-1800s <strong>to</strong> the present<br />

is common knowledge. Chairman of the corrupt ASV and “devoted ecumenist Philip<br />

Schaff” was on the ABS “Versions Committee” during the production and publication of<br />

the 1865 Spanish edition. (The earlier and original American Bible Society was<br />

conservative and required translations <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> made from the King James Bible and forbad<br />

transla<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> used Greek and Hebrew <strong>to</strong>ols. For this reason they rejected Judson’s Bible.<br />

The next generation, influenced by Unitarians, allowed the use of the corrupt Greek and<br />

Hebrew <strong>to</strong>ols.) (An American Bible, Paul C. Gutjahr, Stanford, CA: Stanford University<br />

Press, 1999, Ch. 3, p. 106, 110 et al.; ABS His<strong>to</strong>rical Essay #16, pp. 5, 12; G.A.<br />

Riplinger, Hazardous Materials: Greek and Hebrew Study Dangers, Ararat, VA: AV<br />

Publications, p. 164 et al.).)<br />

Some recent editions of the 1865 Spanish Bible change John 1:9, altering its<br />

longstanding “Aquel Verbo” <strong>to</strong> “Aquella Palabra.” This suggests that there is<br />

recognition that “Palabra” is the original 1865 reading in other verses, which should<br />

likewise <strong>be</strong> res<strong>to</strong>red in all verses, not just one.<br />

8.) They must <strong>be</strong>lieve that the source for translating Bibles is lexicons and<br />

dictionaries by unsaved li<strong>be</strong>rals, and not by comparing “spiritual things with<br />

spiritual” in cognate language Bibles.<br />

9.) They must pretend <strong>to</strong> those who are unfamiliar with Greek texts that they are<br />

replicating the divergent words logos and hrema, as <strong>see</strong>n in Greek texts. But they<br />

are not disclosing <strong>to</strong> their non-Greek-speaking readers that their Bible does not<br />

replicate the distinction <strong>be</strong>tween the over 220 uses of logos and the over 50 uses<br />

of hrema. No vernacular Bible does, which indicates that God apparently hasn’t<br />

read the man-made lexicons, which garner their definitions of these two words<br />

14

from sources outside of Biblical contexts. The discussion at hand is <strong>how</strong> <strong>to</strong><br />

translate logos, where Christ is named. Christ is never called the hrema. The KJB<br />

and all Bibles do not distinguish <strong>be</strong>tween logos and hrema when referring <strong>to</strong> the<br />

‘word’ of God and neither do Bibles which use Verbo for Christ, the Word.<br />

Most importantly, they must ignore one of the most important cross-reference in the<br />

entire Bible, that of Jesus, the Word and the word of God.<br />

Tyndale <strong>to</strong> Coverdale <strong>to</strong> Geneva <strong>to</strong> KJB: Revisited<br />

Therefore, any Bible which uses Verbo in John 1:1 must <strong>be</strong> rejected and replaced by a<br />

Spanish Bible that uses the his<strong>to</strong>ric Palabra. Such a Spanish Bible is now back in print,<br />

the 1602 Valera Purificada. Those who have printed Spanish Bibles in the interim, such<br />

as the 1865 and the Gómez, should <strong>be</strong> commended for giving the Spanish world<br />

something <strong>be</strong>tter than the tainted 1960 edition. These printers and transla<strong>to</strong>rs will go<br />

down in his<strong>to</strong>ry, as great Christians, for locating and circulating the <strong>be</strong>st then available<br />

Spanish Bible. While others sat and did nothing, these men attempted <strong>to</strong> fill the gap with<br />

the <strong>be</strong>st translation they could find or produce.<br />

The dates of editions (e.g. 1865) are not a definitive measure of their worthiness. For<br />

example, assuming that pre-Westcott and Hort Bibles (pre-1881) are pure and ‘pre-<br />

Laodician,’ is not full-proof. Writing dates in the white spaces of the Bible is courting<br />

error. The Memoir of Adoniram Judson Being a Sketch of His Life and Missionary Labors quotes<br />

Judson as saying that he and “all the world” followed the Griesbach Greek text in the early 1800s.<br />

That text is a precursor of Westcott and Hort and is nearly as corrupt. Judson admits his use of it<br />

saying,<br />

“In my first attempts at translating portions of the New Testament, above 20<br />

years ago, I followed Griesbach, as all the world then did; and though, from year<br />

<strong>to</strong> year I have found reason <strong>to</strong> distrust his authority, still, not wishing <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> everchanging,<br />

I deviated but little from his text, in subsequent editions, until the<br />

last…” (NY: J. Clement [C. M. Sax<strong>to</strong>n, Baker & Co], 1860, pp. 237-239).<br />

My purchase of an expensive old 1863 Pash<strong>to</strong> Bible, in an effort <strong>to</strong> find an<br />

uncorrupted text in that Indian dialect, proved disappointing, as the textual errors of<br />

Griesbach’s Greek text of the early 1800s had crept in in a num<strong>be</strong>r of places. Biblical<br />

criticism was wide-spread in the 1800s. Simple criteria, such as picking good dates and<br />

bad dates for Bibles, must give way <strong>to</strong> word-for-word collation and comparison with<br />

his<strong>to</strong>rical editions.<br />

Using older versions, such as the 1865, is far <strong>be</strong>tter that patching current modern<br />

Spanish editions (e.g. 1960) with readings from the Textus Receptus (i.e. Gómez), while<br />

keeping some of their modern vocabulary, <strong>to</strong> which some readers have <strong>be</strong>come<br />

accus<strong>to</strong>med. Such can only <strong>be</strong> <strong>see</strong>n as a good s<strong>to</strong>p-gap measure.<br />

The Holy Bible is serious business (Rev. 22:19), which allows no one <strong>to</strong> “take away”<br />

the his<strong>to</strong>rically sanctioned word for ‘Word,’ used by all pure Romance language Bibles<br />

in all eras. Critics must take away this blinding <strong>be</strong>am, so that they can <strong>see</strong> clearly <strong>to</strong><br />

discuss any tiny specks they may <strong>see</strong> in the 1602 Purificada.<br />

15

The Catholic church has had such a strong-hold in Spanish-speaking countries<br />

that the Spanish Bible <strong>see</strong>ms <strong>to</strong> just now <strong>be</strong> at a slightly similar point in his<strong>to</strong>ry that the<br />

English Bible was at in the mid-1500s. (The his<strong>to</strong>rical English text had never experienced<br />

the bald textual deviations <strong>see</strong>n in some Spanish editions.) In the 1500s Coverdale<br />

worked with Tyndale and later went on <strong>to</strong> improve upon Tyndale’s work, ever so slightly.<br />

Coverdale then went on <strong>to</strong> produce the Great Bible, with its tiny changes, and even later<br />

worked on the Geneva Bible. Renderings from all of these Bibles then went on <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong>come<br />

a part of the King James Bible. This all happened within a very short compass of time. A<br />

person could have lived <strong>to</strong> <strong>see</strong> Tyndale’s New Testament in 1534 and the KJB in 1611.<br />

Evidently Coverdale felt loyalty <strong>to</strong> nothing but the word of God. A cooperative spirit<br />

must have <strong>be</strong>en maintained. God does not <strong>see</strong>m <strong>to</strong> have minded, as the KJB s<strong>how</strong>s<br />

English word-choices from all of these texts, and a few original ones. Coverdale was not<br />

wrong <strong>to</strong> work <strong>to</strong>wards the printing of the Geneva Bible. When we think of heroes, we<br />

think of him <strong>to</strong>day. Similarly, those who printed the 1865 and Gómez were not wrong <strong>to</strong><br />

do this. But those who held on <strong>to</strong> their Geneva’s, when God had brought forth a more<br />

finished product, were missing a blessing, indeed. God had <strong>to</strong> provide a Bible <strong>to</strong> use<br />

during the seven years the KJB was <strong>be</strong>ing made. And God provided Bibles while the<br />

Purificada was <strong>be</strong>ing made, and “great was the company of those that published it,” (Ps.<br />

68:11), including our modern day heroes, Local Church Bible Publishers, The Valera<br />

Bible Society, Chick Publications, and the many local church printers, <strong>to</strong>o numerous <strong>to</strong><br />

name.<br />

There are now several concurrent Spanish editions which have removed most<br />

critical text readings. We are <strong>be</strong>tter off, not worse off, <strong>be</strong>cause of those who s<strong>to</strong>od in the<br />

gap, like Coverdale, Gómez, and those, who through great personal sacrifice, found or<br />

printed the 1865. Luther himself had a few textual errors. And is Luther not the hero of<br />

the German Bible yet <strong>to</strong>day? The deviations in these texts are but a small part of a<br />

generally stable whole. As the KJB transla<strong>to</strong>rs said, their predecessors’ work was solid,<br />

but their work would shine forth, <strong>be</strong>ing brightly polished. The sun is setting on the tender<br />

Spanish bud and will yet rise on a trustier vine. Now, the pure Spanish Bible is <strong>see</strong>ing the<br />

light of day again in almost every detail in the 1602 Valera Purificada. That light will<br />

grow brighter yet. The body of Christ, the priesthood of <strong>be</strong>lievers, will recognize any<br />

small dissonant spots and settle upon those that ring true. This does not happen over<br />

night, but occurs as evaluation copies circulate. The final solution is just around the<br />

corner, if cooperation, humility, and the face of the Lord is sought. Without the printing<br />

of evaluation copies, the body of Christ cannot participate and do their job.<br />

Through my many years of communicating about various readings with those from<br />

Pas<strong>to</strong>r Reyes’s church in Mexico, as they were working on the text of the 1602<br />

Purificada, I observed the following:<br />

1) They had the largest collection of ancient and antique Spanish Bibles at their<br />

finger tips of any group or individual who has set out <strong>to</strong> res<strong>to</strong>re the pure readings.<br />

2) They rejected any modern invention and used only readings which had appeared<br />

in pure Spanish, Romance language, or pure Old Latin scriptures.<br />

3) They were a humble group led by prayer and fasting (James 4:6).<br />

4) They rejected any attempt <strong>to</strong> rush the project, as they recognized the gravity of<br />

handling God’s word.<br />

16

5) They were, first and foremost, a local Independent Baptist church, which spent a<br />

great deal of time evangelizing Central and South America, particularly those<br />

unreached and rugged regions in<strong>to</strong> which few will venture. Their resources go <strong>to</strong><br />

evangelizing and getting actual New Testaments and Bibles in<strong>to</strong> the hands of the<br />

poor, not mailing Americans glossy magazines and paying for expensive video<br />

productions.<br />

6) Every question that I had about their translation was answered with impressive<br />

and voluminous research. In fact, I found myself going <strong>to</strong> them for resources.<br />

This article <strong>see</strong>ks simply <strong>to</strong> bring <strong>to</strong> the present discussion an accurate his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

perspective about one of the words under discussion. God has preserved his words; they<br />

are out there. We simply need <strong>to</strong> examine each one, rationally and with prayer. Then we<br />

must do our job in the preservation process, that is, put ink <strong>to</strong> paper. Printers are the<br />

unsung heroes of Bible preservation, along with the Christians, whose support allows<br />

such printings.<br />

In the <strong>be</strong>ginning was the Word, and he will preserve it, forever, word by word,<br />

particularly God’s name.<br />

“and his name is called The Word of God”<br />

“y su nombre es llamado la Palabra de Dios”<br />

Rev. 19:13.<br />

See Appendix A on the following pages.<br />

17

APPENDIX A<br />

Vernacular Romance Language Bibles Demonstrating<br />

the Use of Palabra and the Rejection of Verbo,<br />

Seen Only in Catholic Texts.<br />

18

SPANISH PROTESTANT BIBLES USE “Palabra”<br />

Reina’s Bible from 1569 uses “Palabra.” But the Catholic editions, done by ‘Padre’ Scio<br />

and Catholic Bishop Amat, use Jerome’s Verbum.<br />

An original Reina (1569 bot<strong>to</strong>m) and Valera (1602 <strong>to</strong>p) both use ‘Palabra’.<br />

Notice the use of the word “Palabra” in Valera’s notes on the left.<br />

19

SPANISH PROTESTANT BIBLES USE “Palabra”<br />

From the very earliest Enzinas of 1543 and the Pineda of 1556, the Spanish have used<br />

Palabra. (Octapla De La Biblia Española: La História de La Biblia Española, Stephen<br />

Hite, New Paris, IN: Sons of Thunder Publishing, n.d.)<br />

20

CATHOLIC FATHER SCIO BEGINS “Verbo”<br />

Roman Catholic priest , ‘Padre’ Father Scio, <strong>to</strong>ok his Catholic Vulgate and<br />

changed God’s name from Palabra, which had <strong>be</strong>en used for many hundreds of years, <strong>to</strong><br />

Verbo, <strong>to</strong> match the corrupt Latin, Verbum. Also notice that the Mora and Pratt 1865<br />

originally had Verbo in John 1:9, as well as in John 1:1. But it has <strong>be</strong>en changed <strong>to</strong><br />

Palabra in just that one place, John 1:9, in some printings of the 1865. If someone<br />

recognized that this should <strong>be</strong> changed, they should have changed all of the places in the<br />

1865 where Verbo is mis-used as God’s name.<br />

21

FRENCH PROTESTANT BIBLES USE “Parolle”<br />

French Olivetan 1535<br />

The Bible of Every Land says it is<br />

“from the original texts” (p. 255)<br />

French Etaples 1530<br />

According <strong>to</strong> the authoritative The Bible of Every<br />

Land the Etaples Bible was “translated from the<br />

Latin” (p. 255). It was published <strong>be</strong>tween 1512<br />

and 1530 in Antwerp by Jaques le Fevre of<br />

Estaples. The Bible of Every Land says<br />

it was used by “Protestants.” (See p. 256 for transcription.)<br />

1541 Bible A de la Haye<br />

22

French Catholic Bibles<br />

<strong>Catholics</strong>, following their Latin Vulgate, introduced a French Catholic Bible in<br />

1550. The Bible of Every Land says it was “revised” in Louvain (p. 255). The title page<br />

says that it was now translated from the “Latin.” If the 1530 Protestant French Bible of<br />

LeFevre, which says parolle, was from “Latin,” and this bible is also from “Latin,” and it<br />

says “ver<strong>be</strong>,” then there must have existed, side by side, two conflicting Latin texts as<br />

late as the 1500s, one Protestant and one Catholic.<br />

By French Catholic J. Tournes in 1551 following the “revised” edition.<br />

23

However, we <strong>see</strong> that Protestants continued <strong>to</strong> publish their pure Bibles, which<br />

say Parole, as <strong>see</strong>n in this 1563 Marlorat (Geneva) edition of the French, published in<br />

Geneva, Switzerland. Even the side notes use the word “parole.”<br />

24

The French Bible by Rebotier from 1561 says, “Parole.”<br />

The French Bible of P. Michel from 1566 also uses “Parole.” Its title page says it was<br />

translated from the Greek in France.<br />

25

PORTUGUESE PROTESTANT BIBLES USE<br />

“Palavra”<br />

A<br />

Almeida, who “converted <strong>to</strong> Protestantism,” produced the first Portuguese<br />

New Testament in 1681 under the auspices of the Dutch government (The<br />

Bible of Every Land, p. 272). It states that, “A Catholic Portuguese<br />

version of the entire Scriptures, from the Vulgate, was published in 23 vols. 12 mo., with<br />

annotations, at Lisbon, 1781-1783 by Don An<strong>to</strong>nio Pereira, an ecclesiastic…” As a<br />

Catholic, he changed the original Portuguese “Palavra” of Almeida <strong>to</strong> “Verbo,” since his<br />

edition was from the Catholic Vulgate.<br />

Indo-Portuguese Bible Uses ‘Palavra”<br />

Indo-Portuguese is spoken on the island of Ceylon and along the coast of India.<br />

Its Bible is the product of Protestant missionary Mr. Newstead in the early 1800s. His<br />

version uses the term “Palavra.”<br />

26

ITALIAN PROTESTANT BIBLES USE “Parola”<br />

O<br />

ne of the earliest Italian Bibles was by Malermi who “was a Benedictine<br />

monk” who made a “translation of the Vulgate.” As a result, he reproduced<br />

Jerome’s ‘Verbum.’ The Italian Protestant translation of Diodoti, Professor of Hebrew at<br />

Geneva, was done in the early 1600s and was “made from the original texts” <strong>to</strong> which it<br />

s<strong>how</strong>s “great fidelity.” Consequently it uses ‘Parola’ in John 1:1. Later, “An Italian<br />

version for the use of Roman <strong>Catholics</strong> was prepared from the Vulgate by Martini,<br />

archbishop of Florence, <strong>to</strong>wards the close of the eighteenth century.” It again copies<br />

Jerome. (The Bible of Every Land, p. 278). In all Romance language Bibles it is evident<br />

that those done by <strong>Catholics</strong> use Verbo and those done by Protestants use a form of<br />

Palabra.<br />

Today,<br />

an edition of the Diodati is still used by Protestant missionaries <strong>to</strong> Italy,<br />

such as Dean Mazzaferri and Sal Galio<strong>to</strong>. On the left is a page from the ‘Diodati’ they<br />

use. It uses Parola, as might <strong>be</strong> expected. It’s title page states, “Traduzione di Giovanni<br />

Diodati, Lucchese, 1576-1649.” Another current edition of the Italian Bible, s<strong>how</strong>n on<br />

the right, is printed in Switzerland by the Gideons.<br />

27

ROMANT, TOULOUSE, VAUDOIS, & PIEDMO NTESE<br />

BIBLES USE VARIANTS of “Parolla ”<br />

T<br />

Romant<br />

he Old Latin language <strong>be</strong>came the Romant (or Provençal) language. Its<br />

scriptures<br />

“<strong>see</strong>ms <strong>to</strong> have <strong>be</strong>en in use among all the nations <strong>to</strong> whom the<br />

Romance dialects were vernacular.” “This version possesses peculiar interest from the<br />

fact of its <strong>be</strong>ing the first translation of the Scriptures in<strong>to</strong> the vernacular language<br />

produced in Europe after the disuse of Latin as the language of common life” (The Bible<br />

of Every Land, p. 282). “The work was condemned and prohibited” by the Pope in 1229.<br />

In John 1:14 it says,<br />

“E la parolla fo<br />

fayta carne e abite en nos…” which is “And the Word was made<br />

flesh and<br />

dwelt among us…”<br />

The<br />

manuscripts, still extant, of these scriptures are one of the <strong>be</strong>st evidences that<br />

as late as 1200, the corrupt Catholic reading ‘verbo’ was rejected by the Waldenses “prior<br />

<strong>to</strong> 1200” (p. 282). (Observe also the use of the word “engenra” for “<strong>be</strong>gotten,” instead of<br />

the corrupt French ‘unique’ <strong>see</strong>n in most modern French versions, except the King James<br />

Francais.)<br />

Toulouse Exhibits “paraoulo”<br />

A dialect of the Provençal in the South of France exhibits the word “paraoulo” in<br />

John 1: 1.<br />

28

Vaudois<br />

The word ‘Parola’ is <strong>see</strong>n in John 1:1 in the Vaudois dialect of the Provençal. The<br />

Bible of<br />

Every Land states that, “The Vaudois, or Waldenses, as they are sometimes<br />

called, maintain <strong>to</strong> this day the pure form of primitive Christianity, <strong>to</strong> which they<br />

steadfastly adhered during the long ages of papal superstition. As a religious body,<br />

<strong>be</strong>aring witness against the corruptions of the Church of Rome, the Waldenses <strong>see</strong>m <strong>to</strong><br />

have originated at a very early period in Southern France; in A.D. 1184 they were<br />

excommunicated by the pope at the Council of Verona, and soon afterwards they spread<br />

themselves in the South of France, the North of Italy, and Germany (p. 284).<br />

Piedmontese (from the foot of the Alps <strong>to</strong> that of the Apennines)<br />

Using<br />

the Protestant word ‘Parola’ puts Bibles in grave danger. “This<br />

Piedmontese<br />

New Testament was among the list of books prohibited at Rome in 1740, by<br />

a decree of the Congregation of the Index of Prohibited Books.” Later, “In 1831, a<br />

translation of the New Testament, faithfully rendered from Martin’s French version in<strong>to</strong><br />

modern Piedmontese, was forwarded <strong>to</strong> the Committee of the British and Foreign Bible<br />

Society, by Lieut.-Colonel Beckwith…This edition was followed, in 1841, by the<br />

publication of a Piedmontese version of the Psalms, executed from Diodati’s Italian<br />

version….Owing <strong>to</strong> the interested opposition of the Romish priesthood, these editions did<br />

not obtain so rapid a circulation as might have <strong>be</strong>en anticipated; and in 1840 the Society’s<br />

version of the New Testament was put on the Index of forbidden books at Rome.” (p.<br />

286).<br />

29

The Bible of Every Land records a comment from 1834 which says that the Bible<br />

was owned by “most of the Protestant families in the can<strong>to</strong>n” of the people who spoke the<br />

dialect of Enghadine. Such a Bible used the word ‘Plaed’, which <strong>see</strong>ms <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> a mix of the<br />

Romance languages (Parola) and the Germanic (Word). This specimen from 1640 s<strong>how</strong>s<br />

the word ‘Plead.’<br />

30

APPENDIX B<br />

A Glimpse in John: Purificada vs. Gόmez vs. 1865<br />

31

A GLIMPS IN JOHN: 1602 Purificada vs. Gόmez vs. 1865<br />

Verse King<br />

James<br />

Bible<br />

John 3:30 He must<br />

Valera 1602<br />

Purificada<br />

Source for<br />

Valera 1602<br />

Purificada<br />

menester (must) not available <strong>to</strong><br />

increase<br />

me<br />

John 3:30 decrease disminuya<br />

All<br />

(decrease)<br />

(Reina, Valera,<br />

etc. matches<br />

Purificada)<br />

Mora and Pratt<br />

1865<br />

conviene (should)<br />

descrecer (literally -<br />

<strong>to</strong> cease <strong>to</strong> grow)<br />

(No other Spanish<br />

Bible matches the<br />

1865 here)<br />

John 3:32 <strong>see</strong>n vis<strong>to</strong> (<strong>see</strong>n) Pineda 1556 vido (saw)<br />

John 3:33 hath set <strong>to</strong><br />

his seal<br />

ha pues<strong>to</strong> su sello a<br />

es<strong>to</strong> (Had placed his<br />

seal [<strong>to</strong> it])<br />

John 3:35 hath given le ha dado<br />

(hath given)<br />

Present tense is<br />

important<br />

John 3:36 not <strong>be</strong>lieve no cree<br />

(not <strong>be</strong>lieve)<br />

John 4:9 askest pides<br />

not available <strong>to</strong><br />

me<br />

este sello<br />

(this seal)<br />

Pineda 1556 dio<br />

(gave)<br />

not available <strong>to</strong> es incredulo<br />

me<br />

(is skeptical)<br />

1909 demandas<br />

(ask)<br />

(demand)<br />

John 4:21 ye vostros (ye) Pineda 1556 omit<br />

John 4:27 <strong>see</strong>kest buscas (<strong>see</strong>k) Enzinas 1543 preguntas<br />

(questions)<br />

John 4:35 the fields los campos Enzinas 1543 las regions<br />

(the fields)<br />

(the regions)<br />

John 4:35 cometh viene (cometh) Pineda 1556<br />

(venga)<br />

hasta (<strong>to</strong>)<br />

John 4:36 <strong>to</strong>gether juntamente Pineda 1556 tambien<br />

(<strong>to</strong>gether)<br />

Enzinas 1543 (also)<br />

John 4:44 own propia<br />

not available <strong>to</strong> omits<br />

(own)<br />

me<br />

John 4:45 when cuando<br />

Enzinas 1543 como<br />

(when)<br />

(quado) (as)<br />

John 4:45 having? habiendo<br />

not available <strong>to</strong> omit<br />

(having)<br />

me<br />

John 4:45 he did el hizo<br />

not available <strong>to</strong> habia hecho<br />

(he did)<br />

me<br />

(had made)<br />

John 4:47 for he was porque estaba para Pineda 1556 porque se<br />

at the point morir<br />

Enzinas 1543 comenzaba a<br />

of death (<strong>be</strong>cause he was<br />

morir<br />

about <strong>to</strong> die)<br />

32<br />

(as he <strong>be</strong>gan <strong>to</strong> die)

Contents of the Chart<br />

As a small part of my lengthy examination of the current Spanish Bibles, I<br />

examined every word in the first four chapters of the book of John <strong>to</strong> determine the extent<br />

and type of differences <strong>be</strong>tween the Valera 1602 Purificada, the Mora and Pratt 1865,<br />

and the Gόmez edition. To demonstrate my findings I have typed up the results for a<br />

compass of sixty consecutive verses. This demonstrates only thirteen verses which<br />

exhibit one word (or so) changes <strong>be</strong>tween the 1865 and the Purificada. It demonstrates<br />

that the Purificada fine-tuned the Spanish Bible by going back <strong>to</strong> earlier Spanish Bibles,<br />

which, not surprisingly, match the KJB exactly. (My earlier word-for-word collation of<br />

the entire Bishops’ New Testament likewise demonstrated that the KJB transla<strong>to</strong>rs also<br />

purified the Bishops’ Bible, by occasionally going back <strong>to</strong> words from earlier English<br />

Bibles, such as changing “win gain” <strong>to</strong> Wycliff’s alliterative “get gain” in James 4:13 and<br />

from the Bishops’ “we the less” <strong>to</strong> Tyndale’s alliterative “we the worse” in 1 Cor. 8:8<br />

(<strong>see</strong> In Awe of Thy Word at http://www.avpublications.com for more examples). The<br />

Purificada simply res<strong>to</strong>red the original Spanish readings.<br />

The 1865 is somewhat like the Geneva Bible; it is generally (not entirely) a good<br />

Received Text Bible, but even the 1909 sometimes retains the old and <strong>be</strong>tter readings,<br />

which the 1865 misses. The purification <strong>be</strong>tween the Purificada and the 1865, like that of<br />

the early English Bibles and the King James, was generally a linguistic one, not a textual<br />

one. In other words, the language was fine-tuned and made more precise by returning <strong>to</strong><br />

the original Spanish reading of Pineda or Enzinas. However, Mora and Pratt’s 1865 have<br />

allowed more actual errors than the English Bible has ever <strong>see</strong>n, <strong>how</strong>ever.<br />

Merely patching a list of things in the 1865 and Gόmez will not address their<br />

problems. The Gomez missed or modernized almost half of the verses checked in the<br />

chart. My word-for-word examination of just four chapters in John indicates that Mora<br />

and Pratt (1865) and Gόmez did not use the oldest, most original and most precise<br />

Spanish readings, but picked a mix of other later readings. The Purificada res<strong>to</strong>res those<br />

pure exact readings. This analysis is not meant <strong>to</strong> s<strong>how</strong> all of the errors in the 1865 and<br />

the Gόmez editions.<br />

33