Marmalade Issue 5, 2017

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

COLLISIONS: IDENTITY,<br />

MEANING AND POLITICS IN<br />

CONTEMPORARY ABORIGINAL<br />

ART AND DESIGN<br />

Words by Timmah Ball<br />

Timmah Ball is an emerging writer, urban researcher<br />

and cultural producer of Ballardong Noongar descent.<br />

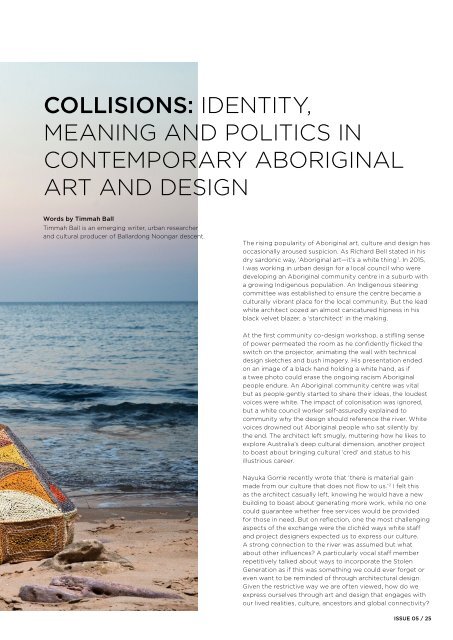

The rising popularity of Aboriginal art, culture and design has<br />

occasionally aroused suspicion. As Richard Bell stated in his<br />

dry sardonic way, ‘Aboriginal art—it’s a white thing ’1 . In 2015,<br />

I was working in urban design for a local council who were<br />

developing an Aboriginal community centre in a suburb with<br />

a growing Indigenous population. An Indigenous steering<br />

committee was established to ensure the centre became a<br />

culturally vibrant place for the local community. But the lead<br />

white architect oozed an almost caricatured hipness in his<br />

black velvet blazer, a ‘starchitect’ in the making.<br />

At the first community co-design workshop, a stifling sense<br />

of power permeated the room as he confidently flicked the<br />

switch on the projector, animating the wall with technical<br />

design sketches and bush imagery. His presentation ended<br />

on an image of a black hand holding a white hand, as if<br />

a twee photo could erase the ongoing racism Aboriginal<br />

people endure. An Aboriginal community centre was vital<br />

but as people gently started to share their ideas, the loudest<br />

voices were white. The impact of colonisation was ignored,<br />

but a white council worker self-assuredly explained to<br />

community why the design should reference the river. White<br />

voices drowned out Aboriginal people who sat silently by<br />

the end. The architect left smugly, muttering how he likes to<br />

explore Australia’s deep cultural dimension, another project<br />

to boast about bringing cultural ‘cred’ and status to his<br />

illustrious career.<br />

Nayuka Gorrie recently wrote that ‘there is material gain<br />

made from our culture that does not flow to us.’ 2 I felt this<br />

as the architect casually left, knowing he would have a new<br />

building to boast about generating more work, while no one<br />

could guarantee whether free services would be provided<br />

for those in need. But on reflection, one the most challenging<br />

aspects of the exchange were the clichéd ways white staff<br />

and project designers expected us to express our culture.<br />

A strong connection to the river was assumed but what<br />

about other influences? A particularly vocal staff member<br />

repetitively talked about ways to incorporate the Stolen<br />

Generation as if this was something we could ever forget or<br />

even want to be reminded of through architectural design.<br />

Given the restrictive way we are often viewed, how do we<br />

express ourselves through art and design that engages with<br />

our lived realities, culture, ancestors and global connectivity?<br />

ISSUE 05 / 25