Der Ring des Nibelungen - Metropolitan Opera

Der Ring des Nibelungen - Metropolitan Opera

Der Ring des Nibelungen - Metropolitan Opera

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

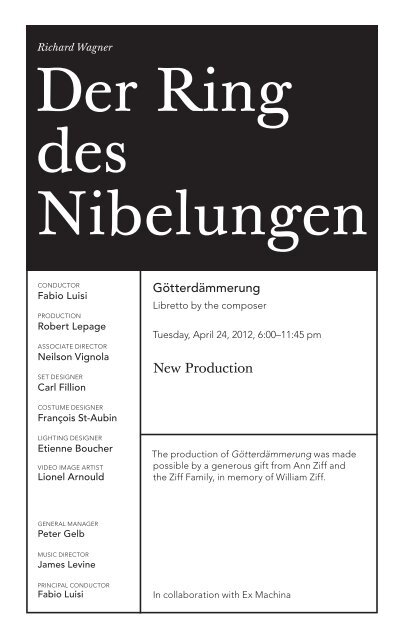

Richard Wagner<br />

<strong>Der</strong> <strong>Ring</strong><br />

<strong>des</strong><br />

<strong>Nibelungen</strong><br />

CONDUCTOR<br />

Fabio Luisi<br />

PRODUCTION<br />

Robert Lepage<br />

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR<br />

Neilson Vignola<br />

SET DESIGNER<br />

Carl Fillion<br />

COSTUME DESIGNER<br />

François St-Aubin<br />

LIGHTING DESIGNER<br />

Etienne Boucher<br />

VIDEO IMAGE ARTIST<br />

Lionel Arnould<br />

GENERAL MANAGER<br />

Peter Gelb<br />

MUSIC DIRECTOR<br />

James Levine<br />

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR<br />

Fabio Luisi<br />

Götterdämmerung<br />

Libretto by the composer<br />

Tuesday, April 24, 2012, 6:00–11:45 pm<br />

New Production<br />

The production of Götterdämmerung was made<br />

possible by a generous gift from Ann Ziff and<br />

the Ziff Family, in memory of William Ziff.<br />

In collaboration with Ex Machina

2011–12 Season<br />

The 230th <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> performance of<br />

Richard Wagner’s<br />

Götterdämmerung<br />

conductor<br />

Fabio Luisi<br />

in order of vocal appearance<br />

First Norn<br />

Maria Radner<br />

Second Norn<br />

Elizabeth Bishop<br />

Third Norn<br />

Heidi Melton<br />

Brünnhilde<br />

Katarina Dalayman<br />

Siegfried<br />

Stephen Gould<br />

Gunther<br />

Iain Paterson<br />

Hagen<br />

Hans-Peter König<br />

Gutrune<br />

Wendy Bryn Harmer *<br />

Waltraute<br />

Karen Cargill DEBUT<br />

Tuesday, April 24, 2012, 6:00–11:45 pm<br />

Alberich<br />

Eric Owens<br />

Woglinde<br />

Erin Morley *<br />

Wellgunde<br />

Jennifer Johnson Cano *<br />

Flosshilde<br />

Tamara Mumford *<br />

stage horn solo<br />

Erik Ralske

A scene from the prologue of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung<br />

Chorus Master Donald Palumbo<br />

Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter<br />

Musical Preparation Linda Hall, John Keenan, Howard Watkins, Carrie-Ann Matheson,<br />

Jonathan Kelly, and John Fisher<br />

Assistant Stage Directors Gina Lapinski, Stephen Pickover, J. Knighten Smit, and<br />

Paula Williams<br />

German Coach Irene Spiegelman<br />

Prompter Carrie-Ann Matheson<br />

Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Scène Éthique<br />

(Varennes, Québec) and <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Shops<br />

Costumes executed by <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Costume Department<br />

Wigs executed by <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong> Wig Department<br />

EX MACHINA PRODUCTION STAFF<br />

Artistic Consultant Rebecca Blankenship<br />

Production Manager Bernard Gilbert, Assistant Viviane Paradis<br />

Technical Director Michel Gosselin, Assistant Éric Gautron<br />

Automation Designer Tobie Horswill, Assistant Stanislas Élie<br />

Video Project Manager Catherine Guay<br />

Initial Interactive Video Designer Holger Förterer<br />

Properties Project Manager Stéphane Longpré<br />

Rig & Safety Adviser Guy St-Amour<br />

Costume Project Manager Charline Boulerice<br />

Puppeteering Consultant Martin Vaillancourt<br />

Musical Consultant Georges Nicholson<br />

Rehearsal Stage Manager Félix Dagenais<br />

Interactive Content Designers Réalisations.net<br />

Production Coordinators Vanessa Landry-Claverie and Nadia Bellefeuille<br />

Producer Michel Bernatchez<br />

Projectors provided by Panasonic<br />

Projection technology consultants Scharff Weisberg<br />

Additional projection equipment Christie Digital<br />

* Graduate of the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program<br />

This performance is made possible in part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts.<br />

Before the performance begins, please switch off cell phones and other electronic<br />

devices. Latecomers will not be admitted during the performance.<br />

Ken Howard/<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>

34<br />

Synopsis<br />

Prologue<br />

scene 1 a high mountain plateau<br />

scene 2 Brünnhilde’s mountaintop<br />

Act I<br />

scene 1 The hall of the Gibichungs on the Rhine<br />

scene 2 Brünnhilde’s mountaintop<br />

Intermission (at APPROXIMATELY 8:00 PM)<br />

Act II<br />

The hall of the Gibichungs<br />

Intermission (at APPROXIMATELY 9:50 PM)<br />

Act III<br />

scene 1 A forest clearing by the Rhine<br />

scene 2 The hall of the Gibichungs<br />

Prologue<br />

At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope<br />

of <strong>des</strong>tiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the world ash tree, from which his spear<br />

was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the<br />

pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly the rope breaks. Their wisdom<br />

ended, the Norns <strong>des</strong>cend into the earth.<br />

Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge.<br />

Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world<br />

to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring he took<br />

from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets<br />

off on his travels.<br />

Act I<br />

In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his halfsiblings,<br />

Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He<br />

suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband.<br />

Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock,<br />

Hagen proposes a plan: a potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall<br />

in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When<br />

Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers<br />

him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.<br />

When Gunther <strong>des</strong>cribes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers<br />

to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. The two men take an<br />

oath of blood brotherhood and set out on their quest.

Waltraute, horrified by the impending <strong>des</strong>truction of Valhalla, comes to<br />

Brünnhilde’s rock, pleading with her sister to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens,<br />

its rightful owners, to save the gods. Brünnhilde refuses, declaring she could<br />

never part with Siegfried’s gift. Waltraute leaves in <strong>des</strong>pair. Hearing Siegfried’s<br />

horn in the distance, Brünnhilde is overjoyed but becomes terrified when a<br />

stranger appears before her, claiming her as Gunther’s bride and tearing the<br />

ring from her hand.<br />

Act II<br />

Outside the Gibichungs’ hall at night, Hagen’s father, Alberich, appears to his<br />

son as if in a dream and reminds him to win back the ring. Dawn breaks and<br />

Siegfried arrives. Hagen summons the Gibichungs to welcome Gunther, who<br />

enters with the humiliated Brünnhilde. When she sees Siegfried, she furiously<br />

denounces him, but he, still under the spell of the potion, doesn’t understand<br />

her anger. Noticing the ring on Siegfried’s finger, Brünnhilde demands to know<br />

who gave it to him, since it was taken from her, supposedly by Gunther, just<br />

the night before. She accuses Siegfried of having stolen the ring and declares<br />

that he is her husband. Siegfried protests, swearing on Hagen’s spear that he<br />

has done no wrong. Brünnhilde now only wants vengeance. Hagen offers to<br />

kill Siegfried, but she explains that she has protected his body with magic—<br />

except for his back, which she knows he would never turn to an enemy. Gunther<br />

hesitatingly joins the conspiracy of murder.<br />

Act III<br />

Siegfried, separated from his hunting party, meets the three Rhinemaidens<br />

by the banks of the river. They ask him to return the ring to them, but he<br />

refuses in order to prove he doesn’t fear its curse. The Rhinemaidens predict<br />

his imminent death and disappear as Hagen, Gunther, and the other hunters<br />

arrive. Encouraged by Hagen, Siegfried tells of his youth and his life with Mime,<br />

the forging of the sword Nothung, and his fight with the dragon. While he is<br />

talking, Hagen makes him drink an antidote to the potion. His memory restored,<br />

Siegfried <strong>des</strong>cribes how he walked through the fire and woke Brünnhilde. At<br />

this, Hagen stabs him in the back with the spear on which Siegfried had sworn.<br />

When Gunther expresses his shock, Hagen claims that he avenged a false oath.<br />

Siegfried remembers Brünnhilde with his last words and dies.<br />

Back at the hall, Gutrune wonders what has happened to Siegfried. When his body<br />

is brought in, she accuses Gunther of murder, who replies that Hagen is to blame.<br />

The two men fight about the ring and Gunther is killed. As Hagen reaches for the<br />

ring, the dead Siegfried threateningly raises his arm. Brünnhilde enters and calmly<br />

orders a funeral pyre to be built on the banks of the Rhine. She denounces the<br />

gods for their guilt in Siegfried’s death, takes the ring from his hand, and promises<br />

it to the Rhinemaidens. Then she lights the pyre and leaps into the flames. The<br />

river overflows its banks and <strong>des</strong>troys the hall. Hagen, trying to get to the ring, is<br />

dragged into the water by the Rhinemaidens, who joyfully reclaim their gold. In<br />

the distance, Valhalla and the gods are seen engulfed in flames.<br />

Visit metopera.org 35

36<br />

In Focus<br />

Richard Wagner<br />

<strong>Der</strong> <strong>Ring</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Nibelungen</strong><br />

Premiere: Bayreuth Festival House, 1876<br />

The <strong>Ring</strong> is a four-day saga depicting the passing of the Old Age of gods,<br />

giants, dwarves, dragons, and nature spirits, and the dawning of the Age of<br />

Man. Wagner, who wrote his own librettos, created a new musical-dramatic<br />

vocabulary to tell this story: characters, things, and ideas are represented by<br />

leitmotifs, or “leading motives,” musical themes that are continually developed<br />

and transformed over the course of the cycle. The <strong>Ring</strong>’s artistic scope is vast<br />

and the musical and aesthetic implications are endless and varied. At its core,<br />

however, it is a drama driven by the actions of a handful of memorable characters.<br />

Chief among these are Wotan, lord of the gods, whose ideals are loftier than<br />

his methods; the magnificently evil dwarf Alberich, the Nibelung of the title; the<br />

loving twins Siegmund and Sieglinde; their savage child Siegfried; and, perhaps<br />

above all, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who encompasses both humanity and divinity.<br />

The Creator<br />

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) was the complex, controversial creator of music–<br />

drama masterpieces that stand at the center of today’s operatic repertory. Born<br />

in Leipzig, Germany, he was an artistic revolutionary who reimagined every<br />

supposition about music and theater. Wagner insisted that words and music<br />

were equals in his works. This approach led to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk,<br />

or “total work of art,” combining music, poetry, architecture, painting, and other<br />

disciplines, a notion that has had an impact on creative fields far beyond opera.<br />

The Setting<br />

The drama of the <strong>Ring</strong> unfolds in a mythical world, at the center of which is<br />

the Rhine river as the embodiment of nature. In the first part of the cycle, Das<br />

Rheingold, the settings are remote and otherwordly: ethereal mountaintops and<br />

caves deep under the earth. Throughout the subsequent operas, the locations<br />

gradually become more familiar as parts of the human world, with only nature<br />

(the Rhine) continuing seamlessly over time.<br />

Götterdämmerung: The Music<br />

The musical ideas set forth in the first three parts of the <strong>Ring</strong> find their full<br />

expression in this opera. Götterdämmerung contains several of the one-onone<br />

confrontations typical of the <strong>Ring</strong>, but a considerable amount of the vocal<br />

writing departs from the forms established in the previous operas. The first

appearance of true ensemble singing in the trio at the end of Act II and the<br />

use of a chorus signify a shift from the rarified world of the gods to an entirely<br />

human perspective. Wagner famously interrupted work on the <strong>Ring</strong> for more<br />

than a decade, while in the midst of writing Siegfried, to compose Tristan und<br />

Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. When he returned to complete the<br />

cycle, his creative abilities had evolved. Perhaps the most striking orchestral<br />

passage of the entire <strong>Ring</strong> is Siegfried’s Funeral Music in Act III, which is built<br />

around a succession of leitmotifs from all parts of the cycle that represent the<br />

hero’s life story, interspersed with the repetition of two thunderous chords that<br />

encapsulate the finality of death. Götterdämmerung presents unique challenges<br />

for the lead tenor and soprano, culminating in a cathartic 15-minute narrative by<br />

Brünnhilde that is among the longest and most powerful unbroken vocal solos<br />

in the operatic repertory.<br />

The <strong>Ring</strong> at the Met<br />

Die Walküre was the first segment of the <strong>Ring</strong> to be heard at the Met, in 1885,<br />

during the company’s second season. Leopold Damrosch conducted a cast that<br />

included two veterans of the Bayreuth Festival, Amalie Materna and Marianne<br />

Brandt. After Damrosch’s death, the remaining <strong>Ring</strong> operas received their<br />

American premieres at the Met between 1887 and 1889, conducted by Wagner’s<br />

former assistant at Bayreuth, Anton Seidl. The complete cycle was presented<br />

eight times in the spring of 1889, including tour performances in Philadelphia,<br />

Boston, Milwaukee, Chicago, and St. Louis. The uncut cycles conducted by<br />

Franz Schalk in 1898–99 began a sequence of 19 consecutive seasons with<br />

<strong>Ring</strong> cycles. Performances resumed after World War I in 1924–25, conducted<br />

by Artur Bodanzky, and continued without interruption until 1945. A production<br />

<strong>des</strong>igned by Lee Simonson, first seen in 1947–48, had a short life and was<br />

succeeded, beginning in 1967, by a new staging directed and conducted by<br />

Herbert von Karajan, with sets by Günther Schneider-Siemssen, that originated<br />

at the Salzburg Easter Festival. It was not completed until 1974–75, without<br />

Karajan, and then had only three cycle performances. Otto Schenk’s production,<br />

with new <strong>des</strong>igns by Schneider-Siemssen, was introduced over three seasons<br />

beginning with Die Walküre on Opening Night 1986. The complete cycle was<br />

first seen in the spring of 1989 and made its final appearance in the 2008–09<br />

season. All 21 cycles of the Schenk production were conducted by James Levine.<br />

The current staging by Robert Lepage, the eighth in the history of the Met, was<br />

unveiled with the premiere of Das Rheingold, again conducted by Maestro<br />

Levine, on Opening Night of the 2010–11 season. This spring’s performances,<br />

conducted by Fabio Luisi, are the first complete cycles of this production.<br />

Visit metopera.org<br />

37

most astounding fact in all Wagner’s career was probably the<br />

writing of the text of Siegfried’s Death in 1848,” says Ernest Newman in<br />

“The<br />

Wagner as Man and Artist. “We can only stand amazed at the audacity<br />

of the conception, the imaginative power the work displays, the artistic growth<br />

it reveals since Lohengrin was written, and the total breach it indicates with the<br />

whole of the operatic art of his time. But Siegfried’s Death was impossible in the<br />

musical idiom of Lohengrin; and Wagner must have known this intuitively.”<br />

Even so, it is unlikely that in November of 1848 Wagner understood that his<br />

new opera would not be completed for deca<strong>des</strong>, or that it would—under the<br />

title Götterdämmerung—be the culmination of one of the greatest masterpieces<br />

in all of Western civilization, <strong>Der</strong> <strong>Ring</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Nibelungen</strong>. Earlier that year Wagner<br />

had finished orchestrating Lohengrin. He was becoming increasingly active in<br />

the political turmoil sweeping Dresden (as well as much of Europe). He also<br />

made sketches for operas based on the lives of Friedrich Barbarossa and Jesus<br />

of Nazareth. That summer he had written the essay “The Wibelungen: Worldhistory<br />

from the Saga,” and later he would write “The Nibelung Myth: As Sketch<br />

for a Drama.” But there is no indication that at this time Wagner was actively<br />

planning on mining the Nibelung saga for more than Siegfried’s Death.<br />

In May of 1849 the uprisings in Dresden were put down. Wanted by the<br />

police for his political activity, Wagner fled, eventually settling in Switzerland.<br />

He produced a number of prose works over the next few years, including the<br />

important <strong>Opera</strong> and Drama, written during the winter of 1850–51, and planned<br />

an opera called Wieland the Smith. In 1850 he also revisited his libretto for<br />

Siegfried’s Death, making some musical sketches.<br />

The more Wagner thought about it, the more he realized that for the story of<br />

the hero’s end to be truly understood by the audience, they needed to know more<br />

about what had gone before. So in 1851 he wrote the libretto to Young Siegfried,<br />

which was then followed (in reverse order) by Die Walküre and Das Rheingold,<br />

spelling out in greater detail why the events of Siegfried’s Death occurred. It was<br />

not until October of 1869—after composing the music for the first three works in<br />

the <strong>Ring</strong>, as well as Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg—that<br />

Wagner again took up the task of creating the music of the drama now known<br />

as Götterdämmerung. The name change reflected a significant shift in the opera<br />

itself, from the death of its hero to the downfall of the gods themselves.<br />

In the earliest version of the story, Brünnhilde took the body of Siegfried<br />

to Valhalla, where his death redeemed the gods. Before igniting Siegfried’s<br />

funeral pyre, she announced, “Hear then, ye mighty Gods; your wrong-doing<br />

is annulled; thank him, the hero who took your guilt upon him…. One only shall<br />

rule, All-Father, Glorious One, Thou [Wotan]. This man [Siegfried] I bring you as<br />

pledge of thy eternal might: good welcome give him, as is his <strong>des</strong>ert!”<br />

There has been much speculation about why Wagner changed the ending<br />

of the <strong>Ring</strong> from this optimistic one, in which Wotan and the gods continued<br />

38<br />

Program Note

to rule, to the ending we know today, in which the gods perish. Sometimes this<br />

shift is attributed to Wagner’s discovery of Schopenhauer’s The World as Will<br />

and Representation, but that did not occur until the end of 1854, at which point<br />

Wagner had completed the text for the <strong>Ring</strong>. Wagner’s optimism about a new<br />

social order for Europe began crumbling as the revolts of 1848 and 1849 were<br />

crushed, and by the time he began making a prose sketch for Young Siegfried<br />

in May of 1851, he noted: “Guilt of the Gods, and their necessary downfall.<br />

Siegfried’s mission. Self-annihilation of the Gods.”<br />

Wagner’s Dresden friend August Röckel, who had only read the libretto<br />

of the <strong>Ring</strong>, asked the composer a question that has puzzled audiences at<br />

Götterdämmerung from the beginning: “Why, seeing that the gold is returned to<br />

the Rhine, is it necessary for the gods to perish?”<br />

“I believe that, at a good performance, even the most naïve spectator will be<br />

left in no doubt on this point,” Wagner replied. “It must be said, however, that<br />

the gods’ downfall is not the result of points in a contract…. No, the necessity of<br />

this downfall arises from our innermost feelings. Thus it was important to justify<br />

this sense of necessity emotionally…. I have once again realized how much of the<br />

work’s meaning (given the nature of my poetic intent) is only made clear by the<br />

music. I can now no longer bear to look at the poem [the libretto] without music.”<br />

Or, as he put it in a letter to Franz Liszt, “The thing shall sound [the italics are<br />

Wagner’s] in such a fashion that people shall hear what they cannot see.”<br />

Thomas Mann brilliantly summed up the relationship between Wagner’s<br />

words and music in the speech he gave on the 50th anniversary of the composer’s<br />

death: “The texts around which it [the music] is woven, which it thereby makes<br />

into drama, are not literature—but the music is. It seems to shoot up like a geyser<br />

from the pre-civilized bedrock depths of myth (and not only ‘seems’; it really<br />

does); but in fact—and at the same time—it is carefully considered, calculated,<br />

supremely intelligent, full of shrewdness and cunning, and as literary in its<br />

conception as the texts are musical in theirs.”<br />

Which is why Wagner knew he could not compose the music of<br />

Götterdämmerung until he had achieved absolute mastery of his compositional<br />

technique, which, he explained to Röckel, had “become a close-knit unity: there<br />

is scarcely a bar in the orchestra that does not develop out of the preceding unit.”<br />

As he composed the <strong>Ring</strong>, Wagner greatly expanded his use of leitmotifs—bits<br />

of melody, harmony, rhythm, even tonality—far beyond merely representing a<br />

character or an object. They became infinitely malleable, and Wagner put them<br />

together in ways that became not only increasingly subtle, but also superbly<br />

expressive, adding layers of drama and emotion to the events taking place on<br />

stage. Even if listeners have no knowledge of the leitmotifs, Wagner’s music is<br />

still enormously potent and can be a life-changing experience.<br />

“Music drama should be about the insi<strong>des</strong> of the characters,” Wagner<br />

said. “The object of music drama is the presentation of archetypal situations as<br />

experienced by the participants [Wagner’s italics], and to this dramatic end music<br />

is a means, albeit a uniquely expressive one.”<br />

At first glance, after the uninterrupted flow of drama in the three preceding<br />

parts of the <strong>Ring</strong>, the libretto of Götterdämmerung might seem a throwback. It has<br />

39

40<br />

Program Note CONTINUED<br />

recognizable, easily excerptable arias, a marvelous love duet, a thrilling swearingof-blood-brotherhood<br />

duet, a chilling vengeance trio, and rousing choruses. But<br />

when Wagner finally began to compose the music for Götterdämmerung he did<br />

not rewrite the libretto, other than to make some changes in the wording of<br />

the final scene. He knew the libretto worked exactly as it should, providing him<br />

with precisely the words and dramatic situations he needed to write some of the<br />

greatest orchestral music ever conceived. And it is through the music that Wagner<br />

can make dramatic points much more vividly than could be made through words.<br />

One of the most shattering parts of Götterdämmerung is Siegfried’s Funeral<br />

Music. Even played in the concert hall, shorn of the rest of the opera, it makes<br />

a tremendous effect. In its proper place during a performance of the full drama,<br />

it is overwhelming. A bit of insight into why this is so comes from the diary of<br />

Wagner’s second wife, Cosima. The entry for September 29, 1871 reads:<br />

‘I have composed a Greek chorus,’ R[ichard] exclaims to me in the<br />

morning, ‘but a chorus which will be sung, so to speak, by the orchestra;<br />

after Siegfried’s death, while the scene is being changed, the Siegmund<br />

theme will be played, as if the chorus were saying: ‘This was his father’;<br />

then the sword motive; and finally his own theme; then the curtain goes<br />

up and Gutrune enters, thinking she had heard his horn. How could<br />

words ever make the impression that these solemn themes, in their new<br />

form, will evoke?’<br />

Cosima does not mention the concept of a Greek chorus in connection with<br />

the Immolation Scene or the great orchestral outpouring that follows Brünnhilde’s<br />

words. But it is impossible not to think of these moments as a magnificent musical<br />

threnody for everything that has gone before. Such a profound summing up of<br />

complex lives, situations, and emotions must be expressed by the orchestra,<br />

because mere words could not do them justice or provide the catharsis that<br />

allows for a true transformation and a new beginning—all of which Wagner’s<br />

music does, perfectly, at the end of Götterdämmerung.<br />

Several years after the <strong>Ring</strong> had been given at Bayreuth in 1876, Cosima<br />

noted in her diary: “In the evening, before supper, [Richard]…glances through<br />

the conclusion of Götterdämmerung, and says that never again will he write<br />

anything as complicated as that.” For many Wagnerians, he never wrote anything<br />

better. —Paul Thomason<br />

Met Titles<br />

To activate, press the red button to the right of the screen in front of your seat and follow the<br />

instructions provided. To turn off the display, press the red button once again. If you have questions<br />

please ask an usher at intermission.<br />

Visit metopera.org

The Cast and Creative Team<br />

Fabio Luisi<br />

conductor (genoa, italy)<br />

this season New productions of Don Giovanni, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, and Manon,<br />

complete <strong>Ring</strong> cycles, and a revival of La Traviata at the Met, concerts with the MET<br />

Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, Manon for his debut at La Scala, and concert engagements with<br />

the Cleveland Orchestra, Filarmonica della Scala, Vienna Symphony, and Oslo Philharmonic.<br />

met appearances Le Nozze di Figaro, Elektra, Hansel and Gretel, Tosca, Lulu, Simon<br />

Boccanegra, Die Ägyptische Helena, Turandot, Ariadne auf Naxos, Rigoletto, Das Rheingold,<br />

and Don Carlo (debut, 2005).<br />

career highlights He is principal conductor of the Met and a frequent guest of the Vienna<br />

State <strong>Opera</strong>, Munich’s Bavarian State <strong>Opera</strong>, and Berlin’s Deutsche Oper and Staatsoper. He<br />

made his Salzburg Festival debut in 2003 leading Strauss’s Die Liebe der Danae (returning<br />

the following season for Die Ägyptische Helena) and his American debut with the Lyric<br />

<strong>Opera</strong> of Chicago leading Rigoletto. He also appears regularly with the Orchestre de Paris,<br />

Bavarian Radio Symphony, Munich Philharmonic, and Rome’s Santa Cecilia Orchestra. He<br />

was music director of the Dresden Staatskapelle and Semperoper from 2007 to 2010 and is<br />

chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony and music director of Japan’s Pacific Music Festival.<br />

Robert Lepage<br />

director (quebec city, canada)<br />

this season Wagner’s <strong>Ring</strong> cycle at the Met.<br />

met production La Damnation de Faust (debut, 2008).<br />

career highlights He is a director, scenic artist, playwright, actor, and film director. In 1984<br />

his play Circulations toured Canada, which was followed by The Dragon’s Trilogy, Vinci,<br />

Polygraph, and Tectonic Plates. He founded his production company, Ex Machina, in 1994<br />

and has produced plays including The Seven Streams of the River Ota and A Midsummer<br />

Night’s Dream. He wrote and directed his first feature film, Le Confessional, in 1994 and<br />

went on to direct the films The Polygraph, Nô, Possible Worlds, and an adaptation of<br />

his play The Far Side of the Moon. In 1997 he opened The Caserne, a multidisciplinary<br />

production center in Quebec City where he and his team have since created and produced<br />

opera productions, film projects, and theatrical and visual works including The Andersen<br />

Project (2005), Lipsynch (2007), The Blue Dragon (2008), Eonnagata (2009), and The Image<br />

Mill (the largest architectural projection ever achieved). He is the creator and director<br />

of Cirque du Soleil’s KÀ (a permanent show in residence in Las Vegas) and Totem, and<br />

directed Peter Gabriel’s Secret World Tour (1993) and his Growing Up Tour (2002). <strong>Opera</strong>tic<br />

directorial projects include The Rake’s Progress at La Monnaie (2007), Lorin Maazel’s 1984<br />

for Covent Garden (2005), Bluebeard’s Castle and Erwartung for the Canadian <strong>Opera</strong><br />

Company (1992), La Damnation de Faust (which was seen in Japan in 1999 and in Paris in<br />

2001, 2004, and 2006), and The Nightingale and Other Short Fables, which has been seen<br />

in Toronto, Aix-en-Provence, Lyon, New York, and Quebec.<br />

41

The Cast and Creative Team CONTINUED<br />

Neilson Vignola<br />

associate director (montreal, canada)<br />

this season Wagner’s <strong>Ring</strong> cycle at the Met.<br />

met production La Damnation de Faust (debut, 2008).<br />

career highlights He has been the director of productions for several festivals in Quebec,<br />

including the International Festival of New Dance and the Festival de Théâtre <strong>des</strong><br />

Amériques. Since 1981 he has worked on numerous productions with the Quebec <strong>Opera</strong>,<br />

and he was the director of productions for the Montreal <strong>Opera</strong> from 1990 to 1993. He has<br />

collaborated with Robert Lepage and Ex Machina on La Damnation de Faust (Japan’s<br />

Saito Kinen Festival and Paris’s Bastille <strong>Opera</strong>), Maazel’s 1984 (Covent Garden), and The<br />

Rake’s Progress (La Monnaie in Brussels). He has also been the technical director and tour<br />

manager for Cirque du Soleil’s Saltimbanco, worked with Lepage on Cirque du Soleil’s<br />

permanent show KÀ, now in residence in Las Vegas, and was the director of creation for<br />

the company’s permanent show Zaia in Macao. He worked again with Lepage on Cirque<br />

du Soleil’s latest touring show, Totem, which opened last May in Montreal.<br />

Carl Fillion<br />

set <strong>des</strong>igner (quebec city, canada)<br />

this season Wagner’s <strong>Ring</strong> cycle at the Met.<br />

met production La Damnation de Faust (debut, 2008).<br />

career highlights Since creating the set <strong>des</strong>igns for Robert Lepage’s play The Seven<br />

Streams of the River Ota in 1993, he has worked with the director and Ex Machina on 15<br />

productions, including Elsinore, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Geometry of Miracles,<br />

La Celestina, Jean-Sans-Nom, and the operas La Damnation de Faust, 1984, The Rake’s<br />

Progress, and The Nightingale and Other Short Fables. In addition to working with<br />

Lepage, he has worked on various productions in Quebec and Europe, including Simon<br />

Boccanegra for Barcelona’s Liceu, The Burial at Thebes for Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, and<br />

Totem (directed by Lepage) for Cirque du Soleil.<br />

François St-Aubin<br />

costume <strong>des</strong>igner (montreal, canada)<br />

this season Wagner’s <strong>Ring</strong> cycle at the Met.<br />

met productions Das Rheingold (debut, 2010).<br />

career highlights He has worked with Robert Lepage since 20007, when he <strong>des</strong>igned<br />

costumes for The Blue Dragon. Since graduating from Canada’s National Theatre School<br />

he has <strong>des</strong>igned costumes for more than 80 theater productions, a dozen operas, and<br />

several contemporary dance companies. Work with Canada’s Stratford Festival inclu<strong>des</strong><br />

costumes for The Count of Monte Cristo, An Ideal Husband, and Don Juan. He has also<br />

42

<strong>des</strong>igned costumes for Carmen for Montreal <strong>Opera</strong>, the Canadian <strong>Opera</strong> Company, and<br />

San Diego <strong>Opera</strong>, and Macbeth in Sydney, Melbourne, and Montreal.<br />

Etienne Boucher<br />

lighting <strong>des</strong>igner (montreal, canada)<br />

this season Wagner’s <strong>Ring</strong> cycle at the Met.<br />

met productions Das Rheingold (debut, 2010).<br />

career highlights He has worked on over 100 productions for theater, dance, musical comedy,<br />

and opera since 1999. He has worked with Ex Machina and Robert Lepage since 2004,<br />

developing their work together on shows including Totem (currently touring with Cirque du<br />

Soleil), La Celestina, Lipsynch, The Rake’s Progress, and The Nightingale and Other Short<br />

Fables. In 2011 he was awarded the Redden Award for Excellence in Lighting Design.<br />

Lionel Arnould<br />

video image artist (quebec city, canada)<br />

this season Götterdämmerung for his debut at the Met.<br />

career highlights He studied at the École <strong>des</strong> Beaux Arts in Épinal, France, and was<br />

introduced to the world of computer graphics in 1991. After moving to Canada in 1995,<br />

he discovered the artistic aspects of multimedia while working on several projects for<br />

Ex Machina (The Dragon’s Trilogy, Busker’s <strong>Opera</strong>, and 1984). Since that time he has<br />

specialized in video projection <strong>des</strong>ign and has worked on numerous contemporary<br />

music projects (including Gryphon Trio’s Constantinople and John Oswald’s Radiant),<br />

contemporary theatre (Théâtre Péril and Théâtre Blanc), and museum installations<br />

(Quebec’s Museum of Civilization).<br />

Karen Cargill<br />

mezzo-soprano (arbroath, scotland)<br />

this season Waltraute in Götterdämmerung at the Deutsche Oper Berlin and for her U.S.<br />

debut at the Met.<br />

career highlights Recent performances include Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia and<br />

Isabella in L’Italiana in Algeri with the Scottish <strong>Opera</strong> and Suzuki in Madama Butterfly<br />

with English National <strong>Opera</strong>. She appears regularly in concerts with the BBC Symphony<br />

and London Philharmonic Orchestras, Hallé Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic,<br />

London Symphony Orchestra, and Scottish Chamber Orchestra. In past seasons she has<br />

sung with the Berlin Philharmonic, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony,<br />

Rotterdam Philharmonic, and Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra. She has also appeared at the<br />

Tanglewood Festival with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Edinburgh Festival with<br />

the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and in recital at London’s Wigmore Hall.<br />

43

44<br />

The Cast and Creative Team CONTINUED<br />

Katarina Dalayman<br />

soprano (stockholm, sweden)<br />

this season Brünnhilde in Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung at the Met, the<br />

Vienna State <strong>Opera</strong>, and Munich’s Bavarian State <strong>Opera</strong>, and her first performances in the<br />

title role of Carmen with Stockholm’s Royal <strong>Opera</strong>.<br />

met appearances Isolde in Tristan und Isolde, Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde (debut, 1999),<br />

the Duchess of Parma in Busoni’s Doktor Faust, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Lisa in The<br />

Queen of Spa<strong>des</strong>, and Marie in Wozzeck.<br />

career highlights She has sung the title role of Elektra, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier,<br />

and Brünnhilde in <strong>Ring</strong> performances in Stockholm; Brünnhilde in Siegfried at the Aix-en-<br />

Provence Festival; Desdemona in Otello, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Mimì<br />

in La Bohème, and Elisabeth in Tannhäuser in Stuttgart; Marie at Covent Garden and<br />

Paris; Ariadne in Ariadne auf Naxos in Paris, Brussels, Dresden, and Munich; Tosca in<br />

Copenhagen and Berlin; Lisa with Lyric <strong>Opera</strong> of Chicago and in Munich; the Duchess of<br />

Parma at the Salzburg Festival; Judith in Bluebeard’s Castle at Covent Garden; and Kundry<br />

in Parsifal at Paris’s Bastille <strong>Opera</strong>.<br />

Wendy Bryn Harmer<br />

soprano (roseville, california)<br />

this season Freia in Das Rheingold, Ortlinde in Die Walküre, Gutrune in Götterdämmerung,<br />

and Emma in Khovanshchina at the Met and a concert with the Boston Conservatory.<br />

met appearances The First Lady in The Magic Flute, Chloë in The Queen of Spa<strong>des</strong>, the<br />

Third Norn in Götterdämmerung, First Bri<strong>des</strong>maid in Le Nozze di Figaro (debut, 2005),<br />

a Flower Maiden in Parsifal, Barena in Jen ° ufa, a Servant in Die Ägyptische Helena, and<br />

Dunyasha in War and Peace.<br />

career highlights Recent performances include Glauce in Cherubini’s Medea for her debut<br />

at the Glimmerglass <strong>Opera</strong>, Wanda in Offenbach’s La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein<br />

and Vitellia in La Clemenza di Tito with <strong>Opera</strong> Boston, Adalgisa in Norma at the Palm<br />

Beach <strong>Opera</strong>, Mimì in La Bohème at the Utah <strong>Opera</strong> Festival, and Gerhilde in Die Walküre<br />

for her debut with the San Francisco <strong>Opera</strong>. She is a graduate of the Met’s Lindemann<br />

Young Artist Development Program.

Stephen Gould<br />

tenor (roanoke, virginia)<br />

this season Siegfried in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung at the Met, Munich’s Bavarian<br />

State <strong>Opera</strong>, and Vienna State <strong>Opera</strong>, and the title role of Tannhäuser with the Vienna<br />

State <strong>Opera</strong>.<br />

met appearances Erik in <strong>Der</strong> Fliegende Holländer (debut, 2010).<br />

career highlights He has sung Tannhäuser in Paris, Erik with Munich’s Bavarian State <strong>Opera</strong>,<br />

Siegfried in <strong>Ring</strong> cycles and Tannhäuser at the Bayreuth Festival, Bacchus in Ariadne auf<br />

Naxos and Parsifal in Graz, Florestan in Fidelio in Rome, and Parsifal at the Vienna State<br />

<strong>Opera</strong>. Concert engagements include Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the Chicago<br />

Symphony Orchestra; Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Atlantic Symphony Orchestra<br />

in Berlin and Munich; Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder in Montreal, Berlin, Brussels, Amsterdam,<br />

and Helsinki; and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 at the Bergen Festival, Carnegie Hall, and in<br />

Paris, Vienna, and Budapest.<br />

Hans-Peter König<br />

bass (düsseldorf, germany)<br />

this season Fafner in Das Rheingold and Siegfried, Hunding in Die Walküre, and Hagen<br />

in Götterdämmerung at the Met, Osmin in Die Entführung aus dem Serail in Duisburg,<br />

Hunding in Düsseldorf, and Hagen in Munich.<br />

met appearances Fafner, Hunding, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte (debut, 2010), and Daland in<br />

<strong>Der</strong> Fliegende Holländer.<br />

career highlights A member of Düsseldorf’s Deutsche Oper am Rhein, he was awarded<br />

the title of Kammersänger there for his outstanding contributions to music. His wideranging<br />

repertoire encompasses leading bass roles of Wagner, Verdi, Mozart, Tchaikovsky,<br />

and Strauss, among others, which he has sung with many of the world’s leading opera<br />

companies. He has appeared as a guest artist at opera houses and festivals including<br />

Covent Garden, the Bayreuth Festival, the Baden-Baden Festival, La Scala, Deutsche Oper<br />

Berlin, Barcelona’s Liceu, Florence’s Maggio Musicale, and Munich’s Bavarian State <strong>Opera</strong>,<br />

as well as in Dresden, Tokyo, Hamburg, and São Paulo.<br />

45

46<br />

The Cast and Creative Team CONTINUED<br />

Eric Owens<br />

bass-baritone (philadelphia, pennsylvania)<br />

this season Alberich in Das Rheingold, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung at the Met; the<br />

Storyteller in John Adams’s A Flowering Tree with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra; and<br />

three appearances at Carnegie Hall: Jochanaan in concert performances of Salome with<br />

the Cleveland Orchestra, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis with the Boston Symphony, and in<br />

recital at Zankel Hall.<br />

met appearances General Leslie Groves in Doctor Atomic (debut, 2008) and Sarastro in The<br />

Magic Flute.<br />

career highlights General Leslie Groves with the San Francisco <strong>Opera</strong> (world premiere)<br />

and Lyric <strong>Opera</strong> of Chicago, Oroveso in Norma at Covent Garden and in Philadelphia,<br />

and Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra, Don Basilio in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, and Porgy in Porgy<br />

and Bess with Washington National <strong>Opera</strong>. He has also sung Ramfis in Aida in Houston,<br />

the Speaker in Die Zauberflöte with Paris’s Bastille <strong>Opera</strong>, Rodolfo in La Sonnambula in<br />

Bordeaux, Ferrando in Il Trovatore and Colline in La Bohème in Los Angeles, the title role<br />

of Handel’s Hercules with the Lyric <strong>Opera</strong> of Chicago, and Ramfis in San Francisco.<br />

Iain Paterson<br />

bass-baritone (glasgow, scotland)<br />

this season Gunther in Götterdämmerung at the Met and Munich’s Bavarian State <strong>Opera</strong>,<br />

Figaro in Le Nozze di Figaro with English National <strong>Opera</strong>, and Fasolt in Das Rheingold<br />

with the Detusche Staatsoper Berlin. He also appears in concert with the Cleveland<br />

Orchestra and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic.<br />

met appearances Gunther (debut, 2009).<br />

career highlights Jochanann in Salome and Fasolt for the Salzburg Easter Festival, Gunther<br />

with the Paris <strong>Opera</strong>, Amfortas in Parsifal, Méphistophélès in Faust and Mozart’s Figaro<br />

with English National <strong>Opera</strong>, the title role of Don Giovanni with English National <strong>Opera</strong><br />

and Chicago <strong>Opera</strong> Theater, and Mr. Redburn in Billy Budd at the Glyndebourne Festival.<br />

He has also appeared in concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Melbourne Symphony<br />

Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic<br />

Orchestra, Hallé Orchestra, and Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.<br />

ADDITIONAL EX MACHINA PRODUCTION STAFF<br />

Costume assistant Valérie Deschênes; Costume prototypes Atelier de couture Sonya B.; Properties<br />

production Atelier Sylvain Racine, Christian Hamel, Décors 3D, Général Flight, Productions Yves<br />

Nicol; Lighting assistants Valy Tremblay, Julien Blais-Savoie; Set <strong>des</strong>igner assistants Anna Tusell<br />

Sanchez, Santiago Martos Gonzalez<br />

WORKSHOP PERFORMERS Geneviève Bérubé, Jacinthe Pauzé Boisvert, Daniel Desparois,<br />

François Isabelle, Éric Robidoux, Martin Vaillancourt<br />

lacaserne.net<br />

Yamaha is the official piano of the <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Opera</strong>.<br />

Visit metopera.org