Mapping Meaning, the Journal (Issue No. 4)

Issue theme: Life After the Anthropocene: Envisioning the Futures of the World

Issue theme: Life After the Anthropocene: Envisioning the Futures of the World

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

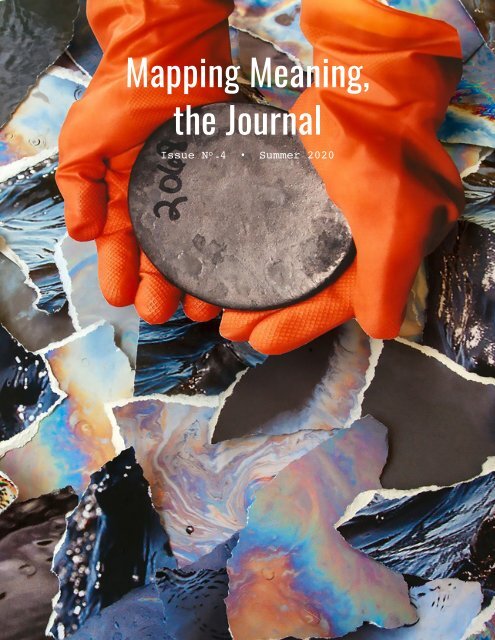

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4 • Summer 2020

The contents of this publication are under a Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) unless<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise specified. Contents may be shared and distributed for noncommercial purposes as<br />

long as proper credit is given to <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> as well as <strong>the</strong> individual author(s).<br />

To view a copy of this license, please visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.<br />

2 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

3

About<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

Minidoka Project, all-female survey crew, Idaho 1918,<br />

Photo of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department of <strong>the</strong> Interior, courtesy of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Bureau of<br />

Reclamation.<br />

4 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

"824 Min Surveying party of<br />

girls on <strong>the</strong><br />

Minidoka project."<br />

Original caption, National Archives<br />

How might interdisciplinary practices promote a<br />

reconsideration of <strong>the</strong> role that humanity plays in a<br />

more-than-human world?<br />

In a strongly fragmented and disciplined-based<br />

world, <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong> offers a collective space<br />

to imagine, create, and propose new models in <strong>the</strong><br />

face of radical global change and ecological and<br />

social crises. Each issue takes up a particular <strong>the</strong>me<br />

and is edited by different curatorial teams from a<br />

variety of disciplines. All issues include <strong>the</strong> broadest<br />

possible calls for submission and ga<strong>the</strong>r toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

divergent and experimental knowledge practices.<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>, is published one to<br />

two times per year.<br />

www.mappingmeaning.org<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

5

6 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Founding<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Melanie Armstrong<br />

Krista Caballero<br />

Nat Castañeda<br />

Sarah Kanouse<br />

Vasia Markides<br />

Jennifer Richter<br />

Carmina Sánchez-del-Valle<br />

Karina Aguilera Skvirsky<br />

Sree Sinha<br />

Trudi Lynn Smith<br />

Sylvia Torti<br />

Linda Wiener<br />

Toni Wynn<br />

Many thanks to <strong>the</strong> Honors College at<br />

<strong>the</strong> University of Utah, which served<br />

as <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>’s partner<br />

and initial fiscal sponsor. Consistent<br />

with <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>’s mentorship<br />

mission, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is committed to<br />

publishing a breadth of work from<br />

those at all stages of <strong>the</strong>ir careers.<br />

Artistic Director: Krista Caballero<br />

Visual Designer: Aliza Jensen<br />

Copy Editor: Corinna Cape<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> Editors:<br />

Melanie Armstrong and Jennifer Richter<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

7

8 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Life After <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

9

Content<br />

12<br />

Introduction<br />

Life After <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene: Envisioning <strong>the</strong><br />

Futures of <strong>the</strong> World<br />

Jennifer Richter and Melanie Armstrong<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> #4 editors<br />

24<br />

Section 1: Experiencing <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene<br />

Image: Shanna Merola, Xylene (C8H10), 2016<br />

27<br />

We All Live Downwind<br />

Shanna Merola<br />

34<br />

Rite of Spring<br />

Liz Ivkovich and Kate Mattingly<br />

53<br />

Field Environmental Philosophy for Post-<br />

Anthropocene Realities: Low Power Radio as<br />

Biocultural Conservation<br />

Rachel Weaver<br />

64<br />

Section 2: Decolonizing <strong>the</strong> Post-<br />

Anthropocene<br />

Image: Shanna Merola, Toluene (C7H8), 2018<br />

66<br />

Inefficiently <strong>Mapping</strong> Boundaries: How is an<br />

urban citizen?<br />

Linda Knight<br />

76<br />

The Europocene: A Past, Present, and Future<br />

Narrative of Climate Change Beginning with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Disruption of Indigenous Relations<br />

Jade Swor, Melanie Armstrong, Taryn Mead, and<br />

Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk<br />

10 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

96<br />

Section 3: Beyond Utopias and Dystopias<br />

Image: Shanna Merola, Ionizing Radiation, 2017<br />

98<br />

Tending Breadth<br />

Jacklyn Brickman and Hea<strong>the</strong>r Taylor<br />

111<br />

Violence, Apocalypse, or a Changing World?<br />

Re-Constructing <strong>the</strong> Climate Imaginary /<br />

Thinking of Doggerland<br />

Evan Tims<br />

128<br />

Section 4: The Past Is <strong>No</strong>t a Predictor for<br />

<strong>the</strong> Future<br />

Image: Shanna Merola, Benzene (C6H6), 2017<br />

130<br />

Gaia Rise: Myths and Politics in <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene<br />

Artemis Herber<br />

149<br />

After Animals<br />

Jay R. Elliott<br />

162<br />

Don’t Pave Paradise<br />

Rosalind Murray and Art O’Neill Mooney<br />

176<br />

The Center for Post-Capitalist History<br />

Leah Sandler<br />

Front and Back Cover Images,<br />

Shanna Merola, Uranium, 2017<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

11

12 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Introduction to<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

Jennifer Richter and Melanie Armstrong<br />

Life After <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene: Envisioning <strong>the</strong><br />

Futures of <strong>the</strong> World<br />

For <strong>the</strong> past six months, scholars, activists, and<br />

artists have worked to continue <strong>the</strong>ir acts of<br />

production in a world that became evermore<br />

uncertain and chaotic. During <strong>the</strong> social unrest<br />

of a global pandemic, we formulated new ways<br />

of working even as we rearranged our kitchens<br />

into offices, constructed virtual classrooms, and<br />

consumed news reports as voraciously as we ate<br />

potato chips. Today, in July 2020, art spaces, <strong>the</strong><br />

academy, and <strong>the</strong> broader world are substantially<br />

transformed from July 2019, when we issued<br />

<strong>the</strong> call for submissions for <strong>the</strong> fourth issue of<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>, on <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me “Life<br />

After <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene: Envisioning <strong>the</strong> Futures<br />

of <strong>the</strong> World.” We ga<strong>the</strong>red contributions in<br />

<strong>the</strong> fall and sorted through <strong>the</strong>m as our social<br />

norms began to unravel during <strong>the</strong> winter. We<br />

revised and edited as we watched a pandemic<br />

expand across <strong>the</strong> globe and protests against<br />

systemic racial injustices rise up. We chatted with<br />

contributors about COVID-19 and George Floyd,<br />

even as we dialogued about tightening a <strong>the</strong>me or<br />

enlivening an argument. These eleven essays and<br />

art pieces became a central part of <strong>the</strong> intellectual<br />

discourse we have used to interpret <strong>the</strong> events<br />

around us. Our perspectives on early 2020 have<br />

been shaped by this collection, none of which<br />

was created specifically in response to events<br />

of <strong>the</strong> last six months, but all of which speaks<br />

to those events in critical ways. Fortunately,<br />

<strong>the</strong> call to imagine a post-Anthropocene world<br />

brought to our attention an array of work that is<br />

simultaneously provocative and hopeful, beautiful<br />

and jarring, and takes a stance of imagination,<br />

play, critique, and action, which are proving to be<br />

vital tools for living in a global pandemic.<br />

Global events occurring in 2020 highlight <strong>the</strong> ways<br />

“control of nature” is both elusive and a persistent<br />

social ideal enacted through <strong>the</strong> management<br />

of human bodies. As political institutions fail to<br />

control <strong>the</strong> biophysical world, <strong>the</strong>y turn instead<br />

to human subjects, managing <strong>the</strong> movement<br />

and positioning of those bodies to achieve <strong>the</strong><br />

objectives of governance, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> health<br />

of people, <strong>the</strong> security of citizens, or <strong>the</strong> growth<br />

of capital. The expansion of globally-dominant,<br />

human-centered economic and political systems<br />

has transformed human relations, but also<br />

produced significant ecological effects. The term<br />

“Anthropocene” is used to highlight how, in<br />

just a few centuries, a small subset of humans,<br />

beginning in Europe and <strong>No</strong>rth America, have<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

13

The call to imagine a post-<br />

Anthropocene world brought<br />

to our attention an array of<br />

work that is simultaneously<br />

provocative and hopeful,<br />

beautiful and jarring, and<br />

takes a stance of imagination,<br />

play, critique, and action,<br />

which are proving to be vital<br />

tools for living in a global<br />

pandemic.<br />

14 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

ecome ever more successful at converting<br />

nature into capital through colonization,<br />

industrialization, imperialism, and financialization<br />

of climate risk and resilience. The ecological<br />

costs have been great, including exponential<br />

decreases in biodiversity, unpredictable and<br />

extreme wea<strong>the</strong>r, and <strong>the</strong> degradation of entire<br />

ecosystems and <strong>the</strong> human/more-than-human<br />

lifeways <strong>the</strong>y support. So, too, are <strong>the</strong> social<br />

costs of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, for <strong>the</strong> accelerated<br />

conversion of “nature” into “resource” is not<br />

consistent with <strong>the</strong> long-term survival, let alone<br />

flourishing, of humanity—or anything else.<br />

The emergence of <strong>the</strong> term Anthropocene two<br />

decades ago has driven planetary scientists to<br />

critically and deeply look for markers of human<br />

influence in <strong>the</strong> geologic record, while humanists<br />

have used <strong>the</strong> term to argue for new ways of<br />

conceptualizing <strong>the</strong> relationship between people<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir planet, and media deploy <strong>the</strong> word<br />

as a headline to bring such debates to a public<br />

audience. The utility of <strong>the</strong> construct of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene is <strong>the</strong> way it binds our attention<br />

to global systems, diverse scales of capital,<br />

and ecological outcomes of social systems. A<br />

limitation is <strong>the</strong> fixation of that attention on<br />

human actions in <strong>the</strong> past and present, to <strong>the</strong><br />

detriment of <strong>the</strong> creative visioning that will be<br />

needed to change global systems.<br />

As news spread of <strong>the</strong> emerging novel<br />

coronavirus, some authors argued that <strong>the</strong> virus<br />

was fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, in<br />

which environmental degradation, systemic<br />

poverty and inequality, and lack of community<br />

services create <strong>the</strong> precise circumstances<br />

needed for viruses to jump species from <strong>the</strong><br />

“wild” to human bodies (De Pascale and Roger,<br />

Kothari et al.). Indeed, disease management<br />

reinforces narratives of power and control of<br />

nature, <strong>the</strong> standard of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> human relationship to microbes has<br />

long been characterized by <strong>the</strong> same desire<br />

to manage nature that has driven capitalism<br />

globally. Situating COVID-19 within <strong>the</strong> broad<br />

environmental discourse of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene<br />

depicts a truly wicked problem. However,<br />

thinking of <strong>the</strong> coronavirus as just ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

product of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene limits <strong>the</strong> ways<br />

<strong>the</strong> human/virus relationship can push us to<br />

think about life after <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene. As<br />

a species understood to be alive through its<br />

complete dependence upon o<strong>the</strong>r species,<br />

viruses exemplify hybridity. Viruses are in our<br />

DNA, and past viral infections altered <strong>the</strong> human<br />

genome in ways that ensure <strong>the</strong> continuance<br />

of our species. When <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene directs<br />

our attention to <strong>the</strong> disproportionate effects<br />

of human activities on <strong>the</strong> planet, we might<br />

consider that microbes have done more to shape<br />

<strong>the</strong> planet than any o<strong>the</strong>r lifeform. The most<br />

dramatic event on earth occurred 2.4 billion years<br />

ago when cyanobacteria transformed <strong>the</strong> planet<br />

to its present, oxygen-rich status and triggered<br />

<strong>the</strong> evolution of multicellularity. When looking<br />

at <strong>the</strong> long history of <strong>the</strong> planet, comprehending<br />

<strong>the</strong> interspecies relationships between humans<br />

and viruses requires post-Anthropocene thinking<br />

about hybridity, evolution, and social relations.<br />

The social transformations of <strong>the</strong> COVID-19<br />

pandemic create an opportunity to realize new<br />

formulations of human relations on and with<br />

<strong>the</strong> planet. As schools and businesses shuttered,<br />

people looked out from <strong>the</strong>ir homes at silent<br />

streets and marveled at how swiftly <strong>the</strong>ir world<br />

seemed to come to a halt. The constraint of<br />

physical touch disrupted <strong>the</strong> interactions that<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

15

most make us human. Stock markets registered<br />

flux as <strong>the</strong> systems that transform labor into<br />

capital slowed. A way of living that was difficult<br />

to imagine a year ago rapidly materialized and<br />

endured weeks longer than many anticipated.<br />

New forms of governance emerged as public<br />

health officials exerted authority over businesses,<br />

elections, and individual behavior, and tensions<br />

between local, national, and global political<br />

institutions flared. Discourses took shape around<br />

“normalcy” and <strong>the</strong> desire to return to or reclaim<br />

something of <strong>the</strong> past. Even as <strong>the</strong> pandemic<br />

persisted and citizens pled for more movement—<br />

some through political protest, many wistfully<br />

in more intimate circles—that past grew more<br />

distant and normalcy became more elusive. This<br />

state of being holds within it opportunities for<br />

deliberation, social contemplation, and political<br />

imagination, perhaps most evident in <strong>the</strong> political<br />

disturbances that emerged during <strong>the</strong> pandemic<br />

in <strong>the</strong> United States, Hong Kong, and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

nations.<br />

The US is currently wracked by new calls for<br />

recognizing and reckoning with a past built<br />

on violence and dispossession. Structural<br />

and systemic racism have defined <strong>the</strong> history<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Americas, and in <strong>the</strong> US specifically,<br />

<strong>the</strong> dispossession of land from Indigenous<br />

communities through displacement, settler<br />

colonialism, and genocide coupled with <strong>the</strong><br />

enslavement of Black bodies for labor are<br />

<strong>the</strong> foundations of American “freedom.” The<br />

Anthropocene lays bare <strong>the</strong> consequences of<br />

capitalism built on <strong>the</strong> exploitation of land and<br />

labor, and of <strong>the</strong> separation of humans from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

humanity. The systemic precarity of economic,<br />

social, political systems all reliant on <strong>the</strong><br />

conversion of nature into natural resources is a<br />

defining feature of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, made clear<br />

through responses to <strong>the</strong> pandemic and <strong>the</strong> calls<br />

for racial justice, as Black and Brown bodies bear<br />

<strong>the</strong> brunt of <strong>the</strong>m both.<br />

Calls for reparations, recognition, and change<br />

in current systems predicated on control and<br />

surveillance of Black and Brown bodies, of<br />

<strong>the</strong> bodies of women and <strong>the</strong> poor, force us<br />

to confront <strong>the</strong> inherent paradoxes of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene that relies on ignoring <strong>the</strong>se<br />

facts. The Movement for Black Lives argues<br />

that we need to recognize calls for “law and<br />

order” as rationales to increase <strong>the</strong> surveilling,<br />

policing, and destruction of poor communities in<br />

increasingly disparate and inequitable ways. The<br />

connections between control of racialized bodies<br />

and control of land and resources are inextricably<br />

linked historically and in <strong>the</strong> future by Black<br />

and Indigenous communities and experiences<br />

(King); in order for new relationships between<br />

humans and <strong>the</strong> biophysical world to come<br />

into being after <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, <strong>the</strong> claims<br />

of communities who have been systematically<br />

degraded need to be acknowledged, recognized<br />

and addressed as fundamental issues of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene. Environments (both internal and<br />

external to <strong>the</strong> human body) as well as capital are<br />

racialized (Pulido); understanding <strong>the</strong> implications<br />

of this racialization is critical for understanding<br />

why addressing climate change will fail if we<br />

do not make connections between all kinds of<br />

environments and justice (Sengupta).<br />

As people wrestle with <strong>the</strong> physical and social<br />

realities <strong>the</strong> first half of 2020 has put before<br />

<strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>y are compelled to examine anew<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir planetary relations, if only through simple<br />

acts like deciding to go outside or leng<strong>the</strong>ning<br />

16 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

In 2020, <strong>the</strong> once nearly<br />

unimaginable ability of an<br />

unseen organism to disrupt<br />

social living has brought<br />

about awe, despair, and<br />

humility, but it has also<br />

demonstrated that human<br />

institutions can change<br />

abruptly and radically, even<br />

if temporarily, due to actions<br />

by people and communities.<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

17

<strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong>y spend at <strong>the</strong> sink washing <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hands. While some point to <strong>the</strong> emergence of<br />

a novel coronavirus as fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene and a consequence of capitalist<br />

pursuits (Loeb), 2020 has also seen citizens<br />

around <strong>the</strong> world collectively demand <strong>the</strong><br />

ability to participate in imagining new futures<br />

and creating <strong>the</strong> societies and governments<br />

capable of constituting <strong>the</strong>m. In 2020, radical<br />

actions like defunding police departments or<br />

voluntary stay-at-home practices have garnered<br />

widespread support, with biophysical effects<br />

such as slowing <strong>the</strong> reproduction and spread<br />

of viruses or potentially reducing atmospheric<br />

carbon emissions. While 2020 has brought awe,<br />

despair, and humility about <strong>the</strong> once nearly<br />

unimaginable ability of an unseen organism to<br />

disrupt social living, it has demonstrated that<br />

human institutions can change abruptly and<br />

radically, even if temporarily, due to behavioral<br />

changes in people and communities. What fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

opportunities does 2020 present for materializing<br />

<strong>the</strong> ways of living in which we have thus far only<br />

dared to dip our toes—imagining in our fiction,<br />

debating in our statehouse, speculating in our<br />

brewpubs, and visualizing in our galleries?<br />

In times of uncertainty and chaos, <strong>the</strong> ways<br />

human lives deeply entwine with <strong>the</strong> physical and<br />

social environment become apparent to more<br />

people. During a state of emergency, imaginative<br />

practices can have a powerful material effect<br />

in envisioning and constituting new worlds.<br />

Diverse visions of how humans should relate to<br />

<strong>the</strong> world have always existed, and audacious<br />

new imaginaries are still being born. These<br />

imaginings chart a post-Anthropocene future<br />

where relationships beyond control exist between<br />

humans and with <strong>the</strong> planet. The present course<br />

invites despair, which can lead to inaction. But<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r visions of how humans should relate to<br />

<strong>the</strong> world have always existed, and audacious<br />

new imaginaries are still being born. They chart<br />

a future in which humans are integrated with <strong>the</strong><br />

world, ra<strong>the</strong>r than in control of it.<br />

Life After <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene: The Works<br />

This issue explores <strong>the</strong> world after <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene, to materialize and make<br />

possible future-thinking in <strong>the</strong> present, and to<br />

demonstrate that paradigm shifts and radical<br />

actions will come from imagining <strong>the</strong> futures<br />

we want and need. Swanson et al. have argued,<br />

“Somehow, in <strong>the</strong> midst of ruins, we must<br />

maintain enough curiosity to notice <strong>the</strong> strange<br />

and wonderful as well as <strong>the</strong> terrible and<br />

terrifying” (M7). The works that follow grapple<br />

with <strong>the</strong>se strange and wonderful aspects<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, as well as <strong>the</strong> terrible<br />

and terrifying. These ideas show recognition,<br />

support, and appreciation for post-Anthropocene<br />

ecological webs, integrate knowledges that<br />

collapse perceived divides between nature and<br />

culture, and think about scales outside of human<br />

time and place. We gain and share insights from<br />

a number of perspectives and methods, including<br />

Indigenous thought, grassroots activism, public<br />

policy, and artistic interventions. These ideas<br />

unfold through diverse forms, including fiction,<br />

critical essays, performance, cinematography, and<br />

artworks.<br />

Collectively and individually, this work investigates<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene through four entry points.<br />

Experiencing <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene: As a starting<br />

point, <strong>the</strong>se pieces define aspects of <strong>the</strong><br />

18 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

experience of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, identifying how<br />

different human communities are making sense<br />

of <strong>the</strong> time we live in by challenging <strong>the</strong> rigidity<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Western human/nature divide. They also<br />

urge us to envision new futures built on <strong>the</strong><br />

recognition of communal and collective pasts<br />

that were centered on deep understandings of<br />

local ecologies, a <strong>the</strong>me that has been central<br />

to <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong> as a collective. A focus on<br />

reclaiming taken-for-granted spaces, used and<br />

discarded by modern society, ignored and wasted,<br />

infuses <strong>the</strong>se interventions into <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene<br />

experience. Shanna Merola’s project, “We All<br />

Live Downwind,” employs photographic collage<br />

to uncover and make manifest <strong>the</strong> polluted<br />

spaces of bodies and land that undergird <strong>the</strong><br />

economic expansion of capitalist systems.<br />

Her work stresses <strong>the</strong> ways that land is made<br />

expendable through uncontrolled longterm<br />

exposure and contamination, explicitly<br />

linking <strong>the</strong> costs of endless extraction and<br />

industrialized production to <strong>the</strong> costs to health<br />

and environment for communities across <strong>the</strong><br />

US, from Detroit, Michigan, to Love Canal, New<br />

York. Similarly, Kate Mattingly and Liz Ivkovich<br />

analyze a dance performance of Rite of Spring<br />

that took place in 2019 beneath an overpass<br />

in an economically-depressed area of Salt<br />

Lake City. They excavate <strong>the</strong> ways a forgotten<br />

industrial urban landscape is imbued with <strong>the</strong><br />

history, labor, and values of <strong>the</strong> cultures and<br />

communities that have previously laid claim to<br />

<strong>the</strong> place. They link those histories to <strong>the</strong> culture<br />

of labor in dance, to underscore <strong>the</strong> precarity<br />

and risk of <strong>the</strong> dancer’s body, as well as <strong>the</strong> ways<br />

that dance can provoke new considerations of<br />

<strong>the</strong> relationships and histories we have with our<br />

local environments. Beyond physical spaces,<br />

Rachel Weaver invites us to consider aural spaces<br />

as sites of reclamation through her application<br />

of field environmental philosophy to local radio<br />

airwaves. Her essay allows us to see more of <strong>the</strong><br />

“soundscape ecologies” that surround us, showing<br />

<strong>the</strong> possibility of reclaiming those spaces for<br />

community needs by understanding low-power<br />

FM radio stations as sites of resistance against<br />

<strong>the</strong> homogenization of radio airwaves. These<br />

works peer into spaces of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene that<br />

epitomize <strong>the</strong> values that drive huge ecological<br />

changes, while also demonstrating ways of<br />

destabilizing and challenging <strong>the</strong> dehumanizing<br />

effects of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene.<br />

Decolonizing <strong>the</strong> post-Anthropocene: Taking<br />

<strong>the</strong> call from Indigenous scholar-activists, a<br />

second <strong>the</strong>me recognizes <strong>the</strong> need to decolonize<br />

our relationships with each o<strong>the</strong>r and <strong>the</strong> world<br />

in order to address climate injustices, fur<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

practices that will lead human societies to reject<br />

processes of colonization and imperialization<br />

(Tuck and Young, Whyte). From its conception,<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong> has challenged scholars to<br />

reconsider <strong>the</strong> colonial powers inscribed in<br />

mapping, and indeed in all disciplinary practices,<br />

by creating spaces to experiment with forms<br />

of knowledge production as a response to <strong>the</strong><br />

current state of ecological emergency. In this<br />

space producers who are often confined by<br />

discourses and methods of a discipline use<br />

cross- and transdisciplinary play to remake<br />

<strong>the</strong> tools <strong>the</strong>y’ve acquired for surveying <strong>the</strong><br />

world, imitating <strong>the</strong> act of resistance of an allwomen<br />

survey crew in 1918 who decorated <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

surveying instruments with stylized hearts and<br />

dashes. Changing <strong>the</strong> tools one uses to describe<br />

<strong>the</strong> world—or creating a new tool outside <strong>the</strong><br />

spaces of capitalism—is a decolonizing practice<br />

that changes <strong>the</strong> world itself. Linda Knight’s<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

19

Envisioning life after <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene forces us to<br />

ask difficult questions,<br />

in order to revolutionize<br />

our relationships to <strong>the</strong><br />

biophysical world and each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

20 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

work in “Inefficient <strong>Mapping</strong>” rejects <strong>the</strong> colonial<br />

practices of mapping which give full power to <strong>the</strong><br />

cartographer to bestow meaning on a landscape.<br />

Ra<strong>the</strong>r she creates alternative protocols that draw<br />

<strong>the</strong> creator’s gaze away from <strong>the</strong> map, connecting<br />

place to map through <strong>the</strong> human body itself.<br />

Her goal is to see <strong>the</strong> pieces of <strong>the</strong> landscape<br />

which have been visually overlooked because<br />

<strong>the</strong>y don’t contribute to <strong>the</strong> work of production,<br />

extraction, and growth, and give <strong>the</strong>m power in<br />

<strong>the</strong> landscape by mapping <strong>the</strong>m. This creates<br />

new places, freed from <strong>the</strong> demands of capital.<br />

Jade Swor et al. propose <strong>the</strong> use of <strong>the</strong> term<br />

“Europocene” to draw attention to <strong>the</strong> systems of<br />

capital rooted in imperialism and colonialism that<br />

have generated and driven <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene.<br />

Enduring Indigenous values offer a means of<br />

decolonizing <strong>the</strong> Europocene and challenging<br />

mechanistic worldviews, to show that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

practices are not emergent, but <strong>the</strong> cyclical and<br />

repeating ways of knowing that have sustained<br />

Indigenous cultures for generations. New<br />

worldviews, new governance, new discourses, and<br />

even new naming practices for <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene<br />

emerge toge<strong>the</strong>r to forge <strong>the</strong> relationships that<br />

will carry over into life after <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene.<br />

Beyond utopias and dystopias: In soliciting<br />

submissions for this issue, we offered <strong>the</strong><br />

particular challenge to represent a post-<br />

Anthropocene future in ways that go beyond<br />

utopias and dystopias, technofixes and fatalism<br />

(Haraway). As Evan Tims points to in critiquing <strong>the</strong><br />

genre of climate fiction, even <strong>the</strong> creative forms<br />

that imagine <strong>the</strong> future in liberating ways often<br />

fall short of creating complex visions of future<br />

ecologies. Dystopian narratives tend to take place<br />

in degraded landscapes, a narrow view of <strong>the</strong><br />

planet’s ecological future, one that may instill<br />

paralyzing fear in those who might o<strong>the</strong>rwise<br />

act to influence <strong>the</strong> political systems that drive<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene. Tims urges those engaged in<br />

speculative climate fiction to present a range of<br />

possible futures in order to broaden our capacity<br />

to imagine how humans will live in a climatealtered<br />

future.<br />

The works contained here present a range of<br />

tools to re-envision different and co-constructive<br />

relationships. In a decolonized future, traditional<br />

ecological knowledges cyclically engage both past<br />

and future political, economic, and biological<br />

processes. Through activism, citizens might<br />

escape <strong>the</strong> dystopian politics of <strong>the</strong> bureaucracy<br />

to establish a complex multispecies citizenship.<br />

Science and technology transform relationships<br />

with animals and elements, place and community.<br />

Art forms invite new relationships between<br />

subject and object, even as <strong>the</strong>y remake materials<br />

into imagined worlds. Such tools reify complex<br />

futures where human experiences endure.<br />

Filmmakers Jacklyn Brickman and Hea<strong>the</strong>r Taylor<br />

playfully embrace <strong>the</strong> concept of caring in <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene, using many tropes of <strong>the</strong> science<br />

fiction genre to imagine crossing into a post-<br />

Anthropocene world. The caregivers in “Tending<br />

Breadth” work in a shiny mylar world encased in<br />

a greenhouse, using <strong>the</strong> technological growing<br />

spaces of <strong>the</strong> past and present to cultivate silvery<br />

future worlds. The connection between care and<br />

world-making runs against <strong>the</strong> assumption of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene that human societies are on track<br />

to destroy worlds, particularly our own. In 2020,<br />

as <strong>the</strong> global pandemic reconfigured political<br />

systems of care, people turned increasingly to a<br />

number of practices traditionally associated with<br />

individualistic care: bread-baking, gardening, pet<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

21

adoption, and more. These intergenerational,<br />

interspecies practices are vibrant and generative<br />

of <strong>the</strong> future, but <strong>the</strong>y also suggest nurturing our<br />

lives in <strong>the</strong> present in hopes that <strong>the</strong>re will be a<br />

future, during a time when <strong>the</strong> character of that<br />

future seems more uncertain than ever. Like a<br />

gardener in a greenhouse, <strong>the</strong>se acts speak to <strong>the</strong><br />

hope of generating society anew.<br />

The past is not a predictor for <strong>the</strong> future:<br />

Envisioning life after <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene forces us<br />

to ask difficult questions, in order to revolutionize<br />

our relationships to <strong>the</strong> biophysical world<br />

and each o<strong>the</strong>r. To destabilize, challenge,<br />

and upend <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, we have to<br />

embrace <strong>the</strong> “ghosts” and “monsters” (Gan et<br />

al.) of our landscapes. Gan et al. argue that,<br />

“Anthropogenic landscapes are also haunted<br />

by imagined futures. We are willing to turn<br />

things into rubble, destroy atmospheres, sell out<br />

companion species in exchange for dreamworlds<br />

of progress” (G2). Instead, progress as a species,<br />

as an ecological sphere, and as a world needs<br />

to acknowledge <strong>the</strong> histories by which our<br />

collective futures will be shaped; “progress” itself<br />

needs to be redefined. Leah Sandler’s “Center<br />

for Post-Capitalist History” fuses toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

capitalist-driven past with <strong>the</strong> archaeology of<br />

<strong>the</strong> future. Her project proposes <strong>the</strong> creation<br />

of a fictitious museum in <strong>the</strong> unspecified future<br />

that will house ironic archives documenting <strong>the</strong><br />

increasing precarity of existence and scarcity<br />

of necessities that mark <strong>the</strong> latter stages of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene. The Center demonstrates <strong>the</strong><br />

logical conclusion of late capitalism, but also<br />

points to post-capitalist possibilities where<br />

interpretations of our cataclysmic age will be<br />

met with curiosity and bewilderment, and <strong>the</strong><br />

recognition that <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene cannot<br />

happen again. In <strong>the</strong> present, Rosalind Murray<br />

and Art Mooney’s activist intervention into a local<br />

development project reveals and challenges<br />

<strong>the</strong> ways environments have been and are<br />

currently assessed, and how political systems<br />

driven by economic narratives operate through<br />

misinformation and deceit. Their struggle to<br />

understand and intervene in <strong>the</strong> development of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir local river in Ireland is a first-hand account<br />

that serves as a model for challenging not only<br />

processes of environmental degradation couched<br />

in terms of economic development, but also<br />

unveiling <strong>the</strong> roots of <strong>the</strong> value systems that<br />

promote long-term environmental change in<br />

exchange for short-term goals.<br />

In <strong>the</strong>se post-Anthropocene places, humans<br />

and non-humans navigate new relationships<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r biological life-forms, including flows<br />

of energy, food, and water, such that our<br />

entanglements with o<strong>the</strong>r species change and<br />

morph into new kinds of relationships. Values<br />

that reduce <strong>the</strong> natural world to resources for<br />

human consumption need to be challenged,<br />

and Jay Elliot’s essay disputes <strong>the</strong> geophysical<br />

grounding of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, looking instead<br />

to <strong>the</strong> biological relationships of modern life that<br />

characterize <strong>the</strong> current moment. He argues<br />

that <strong>the</strong> ways Western society uses animals<br />

in food production push our society into <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene. He interrogates <strong>the</strong> technological<br />

innovations around in-vitro meat to argue for<br />

different relationships with <strong>the</strong> fauna around<br />

us, to recognize how <strong>the</strong>ir existence is knitted to<br />

our own; producing animals from cells does not<br />

recognize <strong>the</strong>ir agency or right to co-exist with<br />

humans.<br />

Finally, Artemis Herber’s large-scale installation<br />

22 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

ings <strong>the</strong> mythic Hellenic past in line with<br />

alternate visions of <strong>the</strong> future. Her artwork<br />

employs found objects and materials taken from<br />

abandoned places like quarries and dumpsters,<br />

giving <strong>the</strong>m new life in her series entitled “Gaia<br />

Rise.” Her pieces link <strong>the</strong> catastrophic present to<br />

<strong>the</strong> mythic past, to call into question <strong>the</strong> roots of<br />

globalized systems of capital that use and discard<br />

people and places, and to raise new possibilities<br />

for life after <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene.<br />

Collectively, <strong>the</strong> works presented in this issue of<br />

<strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong> ask us to interrogate our place<br />

in <strong>the</strong> world, as individuals, community members,<br />

citizens, and global inhabitants. They articulate<br />

<strong>the</strong> paradoxes of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, challenging<br />

<strong>the</strong> ideal of complete human control over nature.<br />

Instead, <strong>the</strong>y offer insights into new relationships<br />

with each o<strong>the</strong>r and o<strong>the</strong>r global denizens,<br />

resisting <strong>the</strong> totalizing and inexorable pull of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene by exposing its precarious<br />

foundations, built on exploitation, contamination,<br />

colonialism, and waste. By envisioning life after<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, we aim to collectively create<br />

new foundations, pulling on histories, presents,<br />

and futures based on care, compassion, and<br />

respect for ourselves and those to come.<br />

Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press, 2019.<br />

Kothari, Ashish et al. “Coronavirus and <strong>the</strong> Crisis of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene.” Ecologist: The <strong>Journal</strong> for <strong>the</strong> Post-Industrial<br />

Age, 27 March 2020, https://<strong>the</strong>ecologist.org/2020/mar/27/<br />

coronavirus-and-crisis-anthropocene.<br />

Loeb, Avi. “A Sobering Astronomical Reminder from<br />

COVID-19.” Scientific American, 18 April 2020, https://blogs.<br />

scientificamerican.com/observations/a-sobering-astronomicalreminder-from-covid-19/.<br />

Pulido, Laura. “Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial<br />

Capitalism.” Capitalism Nature Socialism, vo. 27, 3, 2016, 1-16.<br />

DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013<br />

Sengupta, Somini. “Read Up On <strong>the</strong> Links Between Racism and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Environment.” The New York Times (June 5, 2020). https://<br />

www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/05/climate/racismclimate-change-reading-list.html.<br />

Accessed 21 June 2020.<br />

Swanson, Hea<strong>the</strong>r et al. “Introduction: Bodies Tumbled<br />

into Bodies.” Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Monsters of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing et al. Minneapolis:<br />

University of Minnesota Press, 2017. M1-M12.<br />

Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Young. “Decolonization Is <strong>No</strong>t a<br />

Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vo.<br />

1, 1, 2012, 1-40.<br />

Whyte, Kyle Powys. “The Dakota Access Pipeline,<br />

Environmental Injustice, and U.S. Colonialism.” Red Ink, vo. 19,<br />

1, 2017, 154-169.<br />

Works Cited<br />

De Pascale, Francesco and Roger, Jean-Claude. “Coronavirus:<br />

An Anthropocene's Hybrid? The Need for a Geoethic<br />

Perspective for <strong>the</strong> Future of <strong>the</strong> Earth.” AIMS Geosciences, vo.<br />

6, 2020, 131-134. 10.3934/geosci.2020008.<br />

Gan, Elaine et al. “Introduction: Haunted Landscapes of <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene.” Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Monsters<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene, edited by Anna Tsing et al. Minneapolis:<br />

University of Minnesota Press, 2017. G1-G14.<br />

Haraway, Donna. Staying with <strong>the</strong> Trouble: Making Kin in <strong>the</strong><br />

Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.<br />

King, Tiffany Lethabo. The Black Shoals: Offshore Formation of<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

23

24 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

SECTION 1:<br />

Experiencing <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

25

26 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

We All Live Downwind<br />

Shanna Merola<br />

Shanna Merola<br />

Uranium, 2017<br />

Handmade sculptural collage photographs / Archival inkjet pigment print<br />

Image courtesy of <strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

Artist Statement:<br />

The images in We All Live Downwind are culled<br />

from daily headlines—inspired by global and<br />

grassroots struggles against <strong>the</strong> forces of<br />

privatization in <strong>the</strong> face of disaster capitalism.<br />

In The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein writes about<br />

<strong>the</strong> exploitation of disaster-shocked people and<br />

countries, saying, “<strong>the</strong> original disaster—<strong>the</strong><br />

coup, <strong>the</strong> terrorist attack, <strong>the</strong> market meltdown,<br />

<strong>the</strong> war, <strong>the</strong> tsunami, <strong>the</strong> hurricane—puts <strong>the</strong><br />

entire population into a state of collective shock”<br />

(20). The scenes in We All Live Downwind have<br />

been carved out of dystopian landscapes in <strong>the</strong><br />

aftermath of <strong>the</strong>se events.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> surface, rubble hints at layers of oil and<br />

shale, cracked and bubbling from <strong>the</strong> earth<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

27

elow. Rising from ano<strong>the</strong>r mound, rows of<br />

empty mobile homes bake beneath <strong>the</strong> summer<br />

sun, remnants of <strong>the</strong> bust of small towns left dry<br />

in <strong>the</strong> aftermath of supply and demand. In this<br />

place, only fragments of people remain, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

mechanical gestures left tending to <strong>the</strong> chaos on<br />

auto. Reduced to survival, <strong>the</strong>ir struggle to exist<br />

against an increasingly hostile environment goes<br />

unnoticed. Beyond <strong>the</strong> upheaval of production,<br />

a bending highway promises never ending<br />

expansion - and that low rumble you hear to <strong>the</strong><br />

West is getting louder.<br />

Research and Process<br />

Dioxin, cadmium, arsenic, lead... what happens<br />

over time when <strong>the</strong> human body is exposed to<br />

<strong>the</strong>se elements, and what happens to <strong>the</strong> land?<br />

Since <strong>the</strong> 1960s, sou<strong>the</strong>ast Michigan has become<br />

a dumping ground for corporations looking to<br />

cheaply store and dispose of hazardous waste,<br />

often in <strong>the</strong> backyards of communities of color<br />

and low-income neighborhoods. From uncovered<br />

petroleum coke piles to expanding oil refineries,<br />

residents find <strong>the</strong>mselves teetering on <strong>the</strong> brink<br />

of environmental collapse. Extraction takes what<br />

it needs from <strong>the</strong> earth by force, disrupting<br />

ecosystems and boosting economies. Industrial<br />

waste storage becomes its own market, in turn,<br />

ensuring an endless cycle of wealth production<br />

through <strong>the</strong> exploitation of labor and land. The<br />

photographs in We All Live Downwind examine<br />

<strong>the</strong> human cost of <strong>the</strong>se extractive economies—<br />

across different decades and regions—from my<br />

own neighborhood in Detroit, MI, to Chicago’s<br />

Altgeld Gardens, and Love Canal, NY.<br />

The process for creating each collage begins<br />

with a visual databank. This cache of source<br />

images (a combination of photos I’ve taken at<br />

EPA designated Superfund sites and o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

pulled from <strong>the</strong> Internet) are printed, hand<br />

cut, assembled into <strong>the</strong> environment and rephotographed.<br />

There is often a chaotic violence<br />

to <strong>the</strong> scenes which reference industrial related<br />

health hazards, ecological crisis, and bodies<br />

for exchange in <strong>the</strong> global market. Aerial views<br />

of fracking fields show devastated landscapes,<br />

carved into <strong>the</strong> earth like veins. These<br />

topographies become a surgery room for <strong>the</strong><br />

victims of late-stage capitalism with no option but<br />

to mutate or adapt.<br />

Works Cited<br />

Klein, Naomi (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The rise of disaster<br />

capitalism. London: Penguin.<br />

Bio<br />

Shanna Merola is a visual artist, photojournalist, and legal<br />

worker. In addition to her studio practice, she has been a human<br />

rights observer during political uprisings across <strong>the</strong> country—<br />

from <strong>the</strong> struggle for water rights in Detroit and Flint, MI, to <strong>the</strong><br />

frontlines of Ferguson, MO and Standing Rock, ND. Her collages<br />

and constructed landscapes are informed by <strong>the</strong>se events.<br />

Merola lives in Detroit, MI where she facilitates Know-Your-<br />

Rights workshops and coordinates legal support for grassroots<br />

organizations through <strong>the</strong> National Lawyers Guild. She has<br />

been awarded studio residencies and fellowships through <strong>the</strong><br />

MacDowell Colony, <strong>the</strong> Studios at MASS MoCA, Kala Institute of<br />

Art, <strong>the</strong> Society for Photographic Education, <strong>the</strong> Puffin Foundation,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Merola holds an MFA in<br />

Photography from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a BFA from<br />

Virginia Commonwealth University. Her work has been published<br />

and exhibited both nationally and abroad.<br />

28 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Shanna Merola<br />

Polychlorinated Biphenyl, 2017<br />

Handmade sculptural collage photographs / Archival inkjet pigment print<br />

Image courtesy of <strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> 1920s until <strong>the</strong>y were banned in 1979, an estimated 1.5 billion pounds of <strong>the</strong> toxic compound<br />

known as polychlorinated biphenyls were produced in <strong>No</strong>rth America. For decades, wastes containing<br />

PCBs were cast off into soil-beds, rivers, and wetlands, affecting <strong>the</strong> animals and people around <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

These industrial legacies disproportionately affect communities of color living in <strong>the</strong> shadow of heavy<br />

industry. In a historic housing project on <strong>the</strong> south side of Chicago, <strong>the</strong> residents of Altgeld Gardens<br />

have been waging an environmental justice battle against <strong>the</strong> slow violence of deregulation. Originally<br />

established as federal housing for Black World War II veterans, <strong>the</strong> area would later become known as<br />

<strong>the</strong> “Toxic Doughnut”. Engulfed by factories, landfills, and an incinerator, Altgeld had one of <strong>the</strong> highest<br />

concentrations of hazardous waste sites in <strong>No</strong>rth America. Toxicology studies (98-99’)* from <strong>the</strong> air and<br />

soil revealed dangerous levels of heavy metal neurotoxins causing disproportionate rates of asthma,<br />

birth defects, miscarriages, and cancer.<br />

* People for Community Recovery Archives, Chicago Public Library, Woodson Regional Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection<br />

of Afro-American History and Literature<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

29

Shanna Merola<br />

Uranium, 2017<br />

Handmade sculptural collage photographs / Archival inkjet pigment print<br />

Image courtesy of <strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

In <strong>No</strong>vember of 2019, a nuclear waste contaminated shoreline crumbled into <strong>the</strong> waters of <strong>the</strong><br />

Detroit river, exposing residents to decades-old uranium deposits. The radioactive substance, along<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>r deadly chemicals, had been stored onsite by a WWII era weapons subcontractor for <strong>the</strong><br />

Manhattan Project. Between <strong>the</strong> 1940s and 50s, this facility produced over a thousand tons of uranium<br />

in <strong>the</strong> development of fuel rods for <strong>the</strong> atomic bomb. During this time, factories across <strong>the</strong> country<br />

manufactured materials for atomic weapons to support <strong>the</strong> United States Cold War agenda. Today,<br />

communities from <strong>the</strong> Fort Wayne area in Detroit, MI, to Hunter’s Point in San Francisco, CA, are still<br />

burdened by <strong>the</strong>se nuclear legacies, where government-mandated clean-up efforts range from limited<br />

to non-existent. Kidney disease and cancer are among <strong>the</strong> serious health effects reported by people<br />

with prolonged exposure to enriched uranium.<br />

30 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Shanna Merola<br />

Dibenzodioxin, 2017<br />

Handmade sculptural collage photographs / Archival inkjet pigment print<br />

Image courtesy of <strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

For nearly 30 years, 20,000 tons of submerged chemical waste drums lay undiscovered beneath <strong>the</strong><br />

surface of Love Canal, NY. Situated between Buffalo and Niagara Falls, this sleepy working class town<br />

grew out of <strong>the</strong> region’s 1950s tourism boom. By <strong>the</strong> late 1970s, Love Canal would become a household<br />

name, splashed across <strong>the</strong> headlines of national newspapers as <strong>the</strong> story of corporate negligence<br />

and environmental disaster unfolded. A citizen-led investigation into <strong>the</strong> mysterious health issues of<br />

neighbors impacted by dioxin poisoning incited public outcry along with lawsuits. It also ignited a major<br />

social justice movement at <strong>the</strong> intersection of housing and environmental rights which ultimately led to<br />

<strong>the</strong> creation of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Superfund program. A study of blood samples at Love Canal found significant<br />

chromosomal abnormalities in thirty percent of those tested. This scientific research corresponds with<br />

firsthand testimonials of birth defects, miscarriages, and elevated rates of cancer.<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

31

Shanna Merola<br />

Methane, 2018<br />

Handmade sculptural collage photographs / Archival inkjet pigment print<br />

Image courtesy of <strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

Ruptured pipes and oil storage tanks leeched into Houston’s floodwaters after Hurricane Harvey<br />

devastated whole neighborhoods in <strong>the</strong> summer of 2017. As families searched for dry ground,<br />

factory fires in this highly industrialized city released a toxic cocktail of benzene, butadiene, and<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r carcinogens into <strong>the</strong> surrounding environments. For decades, <strong>the</strong> oil and gas industry had<br />

over-burdened Houston’s predominantly low income and communities of color neighborhoods with<br />

petrochemical waste. In addition, methane emissions from fossil fuel production can aggravate <strong>the</strong><br />

lungs, skin, and eyes. On a normal day <strong>the</strong>se conditions can be untenable, but in <strong>the</strong> face of climate<br />

change induced disaster, elevated levels of human carcinogens can become a matter of life or death.<br />

What efforts have been made on behalf of private corporations to safeguard against future industrial<br />

catastrophes as oceans swell and rising sea levels alter <strong>the</strong> coastal landscapes?<br />

32 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

33

The Anthropocene and <strong>the</strong><br />

Rite of Spring: Performances<br />

of Labor<br />

Kate Mattingly and Liz Ivkovich<br />

June 22, 2019. Walking to <strong>the</strong> elevated stage<br />

beneath an overpass in Salt Lake City, I noticed<br />

my unfamiliar surroundings: railroad tracks,<br />

gravel, chain link fence, and abandoned factories.<br />

This was not <strong>the</strong> typical setting for a performance<br />

of contemporary dance, but NOW-ID, a Utahbased<br />

interdisciplinary company, prides itself on<br />

finding unusual places to set <strong>the</strong>ir performances.<br />

The company, co-directed by choreographer<br />

Charlotte Boye-Christensen and architect Nathan<br />

Webster, created a one-time performance of Igor<br />

Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, held on June 22, 2019.<br />

The platform of uneven risers that served as<br />

<strong>the</strong> stage was set in a landscape of concrete,<br />

brick, and asphalt. Folding chairs surrounded<br />

<strong>the</strong> sides of this elevated stage, so that watching<br />

<strong>the</strong> show gave us a view of fellow audience<br />

members; approximately 250 people attended.<br />

The choreography was exacting and relentless,<br />

generating a series of images, ra<strong>the</strong>r than a<br />

narrative.<br />

The performance began with <strong>the</strong> four dancers<br />

seated on stools at <strong>the</strong> corners of <strong>the</strong> stage.<br />

Evoking boxers waiting on <strong>the</strong> edges of a ring,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y seemed focused and primed. Jo Blake stood,<br />

as if to signal <strong>the</strong> beginning of a ritual, and slowly<br />

walked by <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r dancers (Sydney Sorenson,<br />

Liz Ivkovich, and Tara McArthur) to greet opera<br />

singer Joshua Lindsay as he stepped onto <strong>the</strong><br />

stage and began singing.<br />

When Lindsay had finished singing and exited,<br />

<strong>the</strong> dancing began. Each of <strong>the</strong> four performers<br />

presented distinct qualities––power, extension,<br />

expansion, and speed––while also maintaining a<br />

sense of camaraderie. During unison sections, <strong>the</strong><br />

women generated a sense of solidarity, bounding<br />

across <strong>the</strong> stage with a loping gait that seemed<br />

to gain momentum as <strong>the</strong>y moved. At o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

times, <strong>the</strong> four performers divided into pairs that<br />

suggested rival tribes: Ivkovich and McArthur<br />

wore reddish pants that contrasted with Blake’s<br />

and Sorenson’s attire. In partnering sections,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y seemed to engage in combat, like wrestlers<br />

grappling.<br />

The costumes by Mallory Prucha added to <strong>the</strong><br />

rough and exposed environment: pants were<br />

made of heavy cotton (“monk’s cloth”) but<br />

shredded at <strong>the</strong> hems and stained with dark<br />

streaks. Make-up and hair designs enhanced<br />

this sense of roughness and severity with body<br />

34 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

paint and spiky hairstyles. As <strong>the</strong> performance<br />

continued, <strong>the</strong> body paint disintegrated, leaving<br />

traces of colors just as <strong>the</strong> surroundings<br />

presented traces of former industries and<br />

communities.<br />

Later I would learn that one of <strong>the</strong> four dancers<br />

had split open her toe on a gap in <strong>the</strong> stage<br />

panels during <strong>the</strong> rehearsal before <strong>the</strong> show.<br />

Smears of blood combined with <strong>the</strong> sweat<br />

from previous runs and <strong>the</strong> dust from <strong>the</strong><br />

underpass, none of which had been mopped off<br />

<strong>the</strong> stage. The blurring of this dust, blood, and<br />

sweat left traces and residues, much like <strong>the</strong><br />

patina that covers most of <strong>the</strong> surfaces under<br />

<strong>the</strong> overpass and surrounding buildings. This<br />

layering motivated our analysis of this production<br />

as a site that makes visible <strong>the</strong> dancers’ labor<br />

and exhaustion, as well as <strong>the</strong> limits of artistic<br />

practices, labor relations, and capitalism in <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene.<br />

This introduction was written by Kate, a dance<br />

scholar who attended <strong>the</strong> performance and who<br />

studies dance criticism and its impacts. The rest<br />

of <strong>the</strong> article is co-written with Liz, a dancer in this<br />

Rite who studies performances as contributions<br />

to critical sustainability through corporeal<br />

perspectives. 1 Our approach is both (auto)<br />

ethnographic and <strong>the</strong>oretical, offering an analysis<br />

of <strong>the</strong> performance as a way of elucidating how<br />

tenets of <strong>the</strong> Anthropocene are made visible in<br />

choreographic production. Such choreographies<br />

present a worldview that is characterized by<br />

“human-centered economic and political systems<br />

that have had significant ecological effects so as<br />

to alter <strong>the</strong> course of earth history” (Armstrong<br />

1<br />

We chose to use our first names here to emphasize <strong>the</strong><br />

friendship, familiarity, and collaboration that underpin and<br />

influence this project.<br />

and Richter). Performance also holds <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

to reveal post-Anthropocentric worldviews,<br />

since it is an indeterminate practice, one that<br />

is different each time it is presented, and can<br />

dismantle assumptions about human domination<br />

while imagining new futures.<br />

Prior to <strong>the</strong> June 22, 2019 performance of Rite<br />

of Spring, Liz and Kate collaborated on a series<br />

of blog posts, at <strong>the</strong> request of NOW-ID, that<br />

appeared from April 12 to June 20, 2019 on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

company’s website. These 10 posts speculated on<br />

<strong>the</strong> political and social messages of <strong>the</strong> project,<br />

and through this writing process, we discovered<br />

that <strong>the</strong> human-centric worldview imposed by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Anthropocene finds a haunting parallel in<br />

hierarchies of labor that are favored in making<br />

performances.<br />

Drawing from this writing and from our<br />

experiences of <strong>the</strong> performance, we analyze how<br />

and why dance can be used to challenge <strong>the</strong><br />

Anthropocene, and why <strong>the</strong>se ideas are critical to<br />

thriving in <strong>the</strong> post-Anthropocene. To articulate<br />

<strong>the</strong>se ideas, we incorporate three <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

frameworks: first, <strong>the</strong> concept of entrainment,<br />

which describes how music’s meter is internalized<br />

by a listener, second, ecofeminism, which<br />

connects critiques of patriarchy and capitalism,<br />

and third, decolonizing methodologies, which, as<br />

explained by Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “pose, contest<br />

and struggle for <strong>the</strong> legitimacy of oppositional or<br />

alternative histories, <strong>the</strong>ories and ways of writing”<br />

(40). For us, decolonizing our existing frameworks<br />

means that we address and challenge separations<br />

between humans and our ecologies, and we<br />

recognize labor in dance differently. Ultimately,<br />

we argue that interrogating existing logics of<br />

performance and creative process reveals <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

35

36 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Image 1 | Left to right: Tara<br />

McArthur holds Sydney<br />

Sorenson’s shoulders, Jo Blake<br />

holds Liz Ivkovich. Liz’s black body<br />

paint has cracked and peeled<br />

away at this point, near <strong>the</strong> end of<br />

<strong>the</strong> performance. Photographer:<br />

Jeffrey Juip, Image courtesy of<br />

NOW-ID.<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> N o 4<br />

37

ways capitalist regimes have become naturalized,<br />

and that performance holds <strong>the</strong> potential to<br />

reconfigure how we value labor in dance, as<br />

well as how we value <strong>the</strong> interconnectedness of<br />

humans and ecologies.<br />

The Rituals of <strong>the</strong> Rite of Spring<br />

The Rite of Spring (1913) was a landmark<br />

performance in dance and music canons, bringing<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r Igor Stravinsky as <strong>the</strong> composer,<br />

Vaslav Nijinsky as <strong>the</strong> choreographer, and set<br />

and costume designs by Nicholas Roerich. At<br />

its premiere in Paris on May 29 at <strong>the</strong> Theatre<br />

Champs-Élysées, <strong>the</strong> Rite of Spring was performed<br />

by dancers of <strong>the</strong> Ballets Russes, a company<br />

directed by Sergei Diaghilev. The performance<br />

caused a riot, with audience members shocked<br />

by Stravinsky’s pounding score and Nijinsky’s<br />

contorted and awkward choreography. The<br />

intensity of <strong>the</strong> production and its references<br />

to pagan sacrifice created a stark contrast to<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r performances on <strong>the</strong> program that<br />

evening, namely Michel Fokine’s choreography<br />

of Les Sylphides and Le Spectre de la Rose. Both<br />

of <strong>the</strong>se ballets exemplify <strong>the</strong> demure and<br />

romantic characters that were familiar to balletgoers.<br />

The Rite of Spring was shocking in its sonic<br />

and kinetic angularities, and <strong>the</strong> brutality of <strong>the</strong><br />

woman’s murder. Since that fateful evening,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re have been numerous re-envisionings of <strong>the</strong><br />

performance, by choreographers like Pina Bausch<br />

(1975), Glen Tetley (1974), and Wayne McGregor<br />

(2018), as well as <strong>the</strong> filmmaker Walt Disney<br />

(1940).<br />

The indelible impression of <strong>the</strong>se productions is<br />

a sense of being drawn into <strong>the</strong> musical score: as<br />

we listen to Stravinsky’s music, we internalize its<br />

meter. This connection is called “entrainment.”<br />

Music scholar Pieter C. van den Toorn explains,<br />

“[L]isteners entrain to meter, which in turn<br />

becomes physically a part of us. Entrainment is<br />

automatic (reflexive) as well as subconscious (or<br />

preconscious). Like walking, running, dancing,<br />

and breathing, meter is a kind of motor behavior”<br />

(172). In o<strong>the</strong>r words, when we listen to music,<br />

its meter infiltrates our eardrums, brains, and<br />

nervous systems. Listening is an embodied and<br />

interactive process: it changes us.<br />

In Rite of Spring, disruptions of meter generate a<br />

sense of displacement and irregularity. Scholar<br />

van den Toorn attributes <strong>the</strong> “effect” of Rite on<br />

listeners, to “<strong>the</strong> raw, relentless character of <strong>the</strong><br />

dissonance” (172). The fourth section, “Ritual<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Rival Tribes,” introduces Stravinsky’s<br />

massive stratification. One of several reasons<br />

why <strong>the</strong> first performance of <strong>the</strong> Rite of Spring<br />

provoked such a riotous response was because<br />

<strong>the</strong>se stratifications were unprecedented in<br />

<strong>the</strong> art music of Russia and <strong>the</strong> West, yet <strong>the</strong><br />

polyrhythms and ostinatos in Stravinsky’s score<br />

are also found in African music.<br />

Music that compels us to move may be <strong>the</strong><br />

best evidence of entrainment <strong>the</strong>ories, but<br />

it also points to a more sinister reality. If we<br />

entrain to meter, what else do we internalize?<br />

Thoughts and messages that become part of<br />

our subconscious, also known as implicit bias,<br />

propel our judgments and assumptions. Just as<br />

we internalize music’s meters, we also operate<br />

with internalized value systems that are activated<br />

involuntarily, without awareness or intentional<br />

control. Much of <strong>the</strong> social inequities perpetuated<br />

in our world today can be traced to implicit biases<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir activations in educational, political,<br />

38 <strong>Mapping</strong> <strong>Meaning</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

and legal settings. Systems like capitalism and<br />

consumerism appear “natural” because we have<br />

habituated to <strong>the</strong>ir norms and <strong>the</strong>ir ubiquity. The<br />

fortunate aspect of implicit associations is that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can be gradually unlearned, and this is how<br />

performances contribute to decolonization: <strong>the</strong>y<br />

rewire our bodies and brains. In o<strong>the</strong>r words,<br />

performances shape our perceptions of <strong>the</strong><br />

world because <strong>the</strong>y invite us to feel and think<br />

differently.<br />

When we began writing blog posts prior to <strong>the</strong><br />

performance in 2019, we were faced with a<br />

Sisyphean task: we were adding to more than a<br />

century of discourse about a performance that<br />

is considered genre-changing in both dance<br />

and music histories (see Brandstetter; Eksteins;<br />

Neff). We envisioned <strong>the</strong> role of our writing<br />

as three-fold: expanding perspectives on <strong>the</strong><br />

functions of dance criticism, on this production<br />

and its distinct location in Salt Lake City, and on<br />

its contributions to <strong>the</strong>mes of environmental<br />

sustainability, which were also at <strong>the</strong> core of<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1913 Rite. We view performances as always<br />

imbricated in social, political, cultural and<br />

economic systems that cannot be separated<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir analysis as creative events, and looked<br />

forward to highlighting <strong>the</strong> ways that pre-show<br />

blog posts could offer a reflective platform, a<br />

sounding board, and a container for ideas that<br />

would inform and respond to <strong>the</strong> choreographer’s<br />

process. By situating this performance outdoors,<br />

NOW-ID created a distinct opportunity to<br />

emphasize <strong>the</strong> fraught relationships between<br />

urban development and displacement, and <strong>the</strong><br />

narrative of <strong>the</strong> Rite of Spring is a rich site to<br />

investigate questions about <strong>the</strong> patriarchy, critical<br />

sustainability, and environmental justice.<br />

These <strong>the</strong>mes are particularly apparent in <strong>the</strong><br />

third section of Stravinsky’s score, called <strong>the</strong><br />

“Ritual of Abduction,” which signals <strong>the</strong> violence<br />

that is <strong>the</strong> centerpiece of <strong>the</strong> production. In fact,<br />

Stravinsky originally intended <strong>the</strong> Rite to be called<br />

The Great Sacrifice. According to <strong>the</strong> libretto, in<br />

order for spring to arrive and humanity to thrive,<br />

a Chosen Maiden must dance to death. A sense<br />

of “abduction,” meaning to forcibly take someone<br />

against <strong>the</strong>ir will, exists in many versions of Rite:<br />

by Vaslav Nijinsky, Maurice Bejart, Pina Bausch,<br />

and Anne Bogart & Bill T. Jones. Each of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

performances is characterized by violence and<br />

aggression. As we dug deeper into connections<br />

between violence and patriarchy, we questioned<br />

<strong>the</strong> ongoing need for a woman to die in order for<br />

<strong>the</strong> production to come to close. This is <strong>the</strong> crux<br />

of many versions (by Nijinsky and Bausch) as well<br />

as canonical ballets: La Sylphide, Giselle, Swan Lake,<br />

to name a few. If we go to <strong>the</strong>se performances,<br />