You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

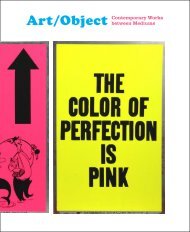

Stanford University<br />

Of Watery Words and Hidden Meanings: Thinking of a Safavid Magic Bowl as an Object of<br />

Mimesis and Innovation<br />

<strong>Arman</strong> <strong>Kassam</strong>, class of 2022<br />

Submission for the <strong>Geballe</strong> <strong>Prize</strong>, category: essay<br />

History / Art History 202B: Coffee, Sugar, and Chocolate: Commodities and Consumption in<br />

World History, 1200-1800 – Winter <strong>2020</strong><br />

Professor Paula Findlen<br />

18 March <strong>2020</strong>

1<br />

Of all the European accounts of the Safavid Empire, the writings of the Huguenot jeweler<br />

Jean Chardin might just be our best window into everyday life in the Empire. Having traveled<br />

extensively throughout modern-day Iran as a royal merchant to Shah Abbas II, Chardin<br />

eventually settled in England in the late 1680’s and began compiling his Voyages, an<br />

embellished record of his life abroad. 1 In one English translation of this record, Chardin<br />

mentions something peculiar about the religious customs of the Safavids: “They believe that all<br />

Men’s Prayers are good and prevalent; therefore, in their illnesses, and in other Wants, they<br />

admit of, and even [use] the Prayers of different Religions: I have seen it practis’d a Thousand<br />

Times.” 2 We should be careful not to take his claims of religious plurality – something he’s seen<br />

“a Thousand Times” – at face-value, but Chardin still captures the spirit of religious life in<br />

Safavid Persia as it intersected with popular medicine. In times of grave illness or epidemic,<br />

Turk and Tajik alike found recourse in a diversity of religious remedies. One such remedy is<br />

connected to an inconspicuous artifact in Stanford University’s Cantor Center: an earthenware<br />

bowl with astrological designs and encircling script, dated to sixteenth-century Persia (fig. 1, fig.<br />

2, fig. 3). This item likely belonged to a magic bowl culture that facilitated spiritual blessings for<br />

the ailing and sinful. Today, these bowls are disproportionately represented by ornately<br />

engraved, prestigious metal objects that belonged to only a minority of political and merchant<br />

elites. The Cantor Center holds what may be one of the few existing Islamic magic bowls that<br />

was crafted from unglazed clay and, by extension, one of the few surviving bowls that likely<br />

belonged to a non-elite milieu. This paper attempts to situate this novel artifact in the history of<br />

1<br />

John Emerson, “Chardin, Sir John,” in Encyclopedia Iranica (Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation, October 13, 2011),<br />

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chardin-sir-john.<br />

2<br />

John Chardin, Sir John Chardin’s Travels in Persia, ed. Edmund Lloyd, N. M. Penzer, and Percy Sykes (London:<br />

Argonaut Press, 1927), 185–86, https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.169543/2015.169543.Sir-John-Chardins-<br />

Travels-In-Persia_djvu.txt.

2<br />

magic bowls and argues that this bowl presents two distinct processes: popularization and<br />

transformation. This bowl shows that the magic-medicinal culture of Safavid Persia diffused<br />

across multiple strata of society and that, upon diffusion, non-elite communities reimagined the<br />

spiritual practices associated with this bowl’s magic. Tied to this otherwise nondescript artifact,<br />

quietly sitting on a shelf in the Cantor Center, is a story of mimesis and a story of innovation.<br />

A Brief History of Islamic Magic Bowls<br />

Magic bowls do not factor into a typical history of Islamic medicine. Traditional<br />

narratives emphasize the Hellenistic influences that became the cornerstones of medical<br />

erudition in madrasahs, formal schools for physicians. 3 The Galenist understanding which<br />

mainstream scholars like Avicenna and Ibn Ridwān subscribed to guided practitioners to think of<br />

their patients on scales of heat and cold, dryness and moistness. Remedies were composed in<br />

response to the humoral makeup of an individual and their respective illness. “Hot” diseases<br />

could be cured with “cold” remedies, “dry” ailments could be treated with an equal and opposite<br />

dose of “moist” medicine, and so forth. 4 Around the twelfth century, another school of medical<br />

thought began to challenge Galenism; proponents of Prophetic medicine argued that cures to<br />

worldly diseases could be found in the holy texts of Islam, the Qur’an and the Hadith, and not in<br />

the materia medica of the Greeks. This tension between the “professional” Greek study of<br />

medicine and Prophetic knowledge has functioned as the traditional framework for thinking<br />

about medical practice in the Islamic world. 5 However, these dominant narratives essentialize a<br />

3<br />

Michael W. Dols and Ibn Ridwān, Medieval Islamic Medicine: Ibn Ridwān’s Treatise “On the Prevention of<br />

Bodily Ills in Egypt” (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 4.<br />

4<br />

Dols and Ibn Ridwān, 15.<br />

5<br />

Andrew J. Newman, “Baqir Al-Majlisī and Islamicate Medicine: Safavid Medical Theory and Practice Re-<br />

Examined,” in Society and Culture in the Early Modern Middle East: Studies on Iran in the Safavid Period (Leiden:<br />

Brill, 2003), 375.

3<br />

dichotomy between two systems of knowledge that likely coexisted. 6 Furthermore, this<br />

framework misses the nearly ubiquitous presence of folklore, thaumaturgy, and popular religion<br />

in everyday medical practice. These magical techniques varied from astrology to numerical<br />

squares to incantations, often times invoking “God’s general beneficence,” seeking his<br />

intervention in everything from dealing with shaytāns (demons) to curing disease. 7 These<br />

practices also interwove themselves with Galenism and Prophetic medicine, making it difficult to<br />

discern where orthodoxy ends and heterodoxy begins. The canon Shi’a text Tibb al-a’Immah<br />

refers several times to Quranic verses written in ink on paper, washed with water, and then<br />

consumed to ameliorate sin. 8 Physicians like Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyah (d. 1350), a Hanbali judge<br />

of Damascus, defended writing on talismans as a cure for fever, nosebleeds, and toothaches. 9 Ibn<br />

Ridwān, himself an adherent to Galenism, defended the use of astrology for diagnosis and<br />

prognosis. 10 Contrary to essentialist narratives of Islamic medicine, medical practice from the<br />

Abbasid Caliphate of the eighth century to the Safavids of the sixteenth developed discursively<br />

between multiple domains of knowledge – Galenist, Prophetic, and thaumaturgical.<br />

The twelfth-century ruler of Syria Nur al-Din ibn Zangi was no exception to this medical<br />

pluralism. He both established a famed bimaristan (hospital) that was run according to Galenist<br />

principles and commissioned the earliest known magic bowl in 1167. 11 The ruler subsequently<br />

6<br />

Justin Stearns, “Writing the History of the Natural Sciences in the Pre-Modern Muslim World: Historiography,<br />

Religion, and the Importance of the Early Modern Period: Natural Science in the Pre-Modern Muslim World,”<br />

History Compass 9, no. 12 (December 2011): 925, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00810.x.<br />

7<br />

Peter E. Pormann and Emilie Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,<br />

2007), 144–45.<br />

8<br />

Emilie Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” in Science, Tools & Magic, Part 1, ed. Julian Raby, vol. 12, n.d.,<br />

72.<br />

9<br />

Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 150.<br />

10<br />

Emilie Savage-Smith, “Medicine,” in Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Technology, Alchemy and<br />

Life Sciences, ed. Rushdī Rāshid and Régis Morelon, Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science (London:<br />

Routledge, 1996), 954–55.<br />

11<br />

Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 73.

4<br />

commissioned a series of other bowls, one of which is currently housed in the Metropolitan<br />

Museum in New York (fig. 4). Suras (verses) from the Qur’an decorate the interior of this bronze<br />

vessel while an exterior encircling script offers us a glimpse into the diseases it treated:<br />

This blessed cup is for every poison. In it have been gathered proven uses, and these are<br />

for the sting of serpent, scorpion and fever, for a woman in labor, the abdominal pain of a<br />

horse caused by eating earth, and the [bites of] a rabid dog, for abdominal pain and colic,<br />

for migraine and throbbing pain, for hepatic and splenic fever, for [increasing] strength,<br />

for [stopping] hemorrhage, for chest pain, for the eye and vision [or evil eye], for<br />

ophthalmia and catarrh, for riyāh al-shawkah [An ulcerated skin disorder or stinging<br />

effects of sand-laden winds], for [driving out] spirits, for releasing the bewitched, and for<br />

all diseases and afflictions. [If] one drinks water or oil or milk from it, then they will be<br />

cured, by the help of God Almighty. 12<br />

The script guides the bowl’s users to treat all afflictions as opposed to specific diseases, thus<br />

presenting the bowl less as a conditional remedy (like those found in Galenism) and more as a<br />

panacea. 13 This breadth of treatment reflects the spiritual logic by which these bowls functioned:<br />

barakah, a divine blessing “from objects associated with [the Prophet or saints].” 14 Normally, a<br />

cleric would recite a passage from the Qur’an over a magic bowl inlaid with script. The barakah<br />

of the Qur’an, tapped into by the spoken and written word, would then transfer to the fluid inside<br />

the bowl. A patient, or in some cases a proxy, would consume this sacred liquid either by<br />

ingestion or ablution. 15 These spiritual practices resonate with a panoply of deeply rooted Islamic<br />

traditions: the ingestion of scripture, the orality of recitation, and the sacrality of water, among<br />

others. Finbarr Barry Flood has suggested that participation in the bowl ritual resulted in an<br />

12<br />

Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 152. The Met’s file on this object can be accessed here:<br />

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/642251. Accession number: MTW 1443.<br />

13<br />

I contend that compared to other medicine of the day, these bowls functioned similar to panaceas, but Savage-<br />

Smith and Pormann also importantly note that bowls from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries disproportionately<br />

specify that they treat snakebites and scorpion stings. A sub-section of these bowls have also been classified as<br />

“poison cups.” Pormann and Savage-Smith, 153.<br />

14<br />

Finbarr Barry Flood, “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity<br />

and Islam,” in Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice, ed. Sally M. Promey (New Haven: Yale<br />

University Press, 2014), 461.<br />

15<br />

Flood, 477; H. Henry Spoer, “Arabic Magic Medicinal Bowls,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 55, no.<br />

3 (September 1935): 256, https://doi.org/10.2307/594826.

5<br />

“ontological collapse” for the participant; drinking the barakah issued forth from the Qur’an was<br />

a fusion of the self with the holy through the sensuality of ingestion. 16 Flood has also claimed<br />

that these rituals stood somewhere in between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, between the<br />

“juridically sanctioned practices of ingesting sacred texts” and the “more popular practices of<br />

consuming images and texts for prophylactic or therapeutic purposes.” 17 Flood’s apt analysis<br />

crucially demonstrates that these bowls were a prominent way of rooting the divine in the<br />

corporeal. Comparable examples to this phenomenon can be drawn from across the globe,<br />

including the spices incorporated in European medieval liturgy and the sacred chocolate imbibed<br />

during Aztec ceremonies. 18 In each of these cases, a sensual consumable bridged the sacred and<br />

the profane. Barakah, therefore, was just as much about the body as it was about the ungraspable<br />

holiness tied to the sacred text.<br />

While all magic bowls follow this logic of rooting the sacred in the profane, the bowls<br />

created after the fifteenth century in Safavid Persia and Ottoman Turkey substantially deviated<br />

from their Egyptian and Syrian predecessors. Of nineteen magic bowls that can be traced back to<br />

Safavid Persia, nearly all of them differ from their antecedents by not bearing exterior directions,<br />

featuring central bosses (fig. 5), and emphasizing the script of the Qur’an. 19 Emilie Savage-Smith<br />

has contended that these changes reflect a movement away from “pre-Islamic symbols” found in<br />

the twelfth century and towards a more rigid orthodoxy, though in Hunt for Paradise she later<br />

identifies three different categories of Safavid magic bowls that attest to the still-prevalent<br />

16<br />

Flood, “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity and Islam,”<br />

482.<br />

17<br />

Flood, 478.<br />

18<br />

M. Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane, Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (Cornell<br />

University Press, 2008); P. Freedman, Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination (Yale University Press,<br />

2008).<br />

19<br />

Emilie Savage-Smith, “Safavid Magic Bowls,” in Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1505–1576<br />

(Milan: Skira, 2003), 241; Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 153. Shi’i verses can also be<br />

found on some bowls – a characteristic that helps identify Safavid origins.

6<br />

influence of folklore: bowls with magic numbers and letters, bowls with zodiacs, and bowls with<br />

magic squares. 20 In fact, despite the rise of strict Prophetic medicine and the suppression of<br />

Sufism and other subaltern sects, thaumaturgy proliferated throughout Safavid Persia. 21 On one<br />

hand, practices including illuminationist doctrine and gnosis acquired legitimacy after being<br />

shepherded into the fold of Shi’ism. 22 On the other hand, the Safavid Empire sustained itself<br />

through contractual obligations that permitted regional differences in belief. Andrew J. Newman<br />

notes, for example, that “considerable political autonomy at the central and provincial level was<br />

the norm and individual discourse, especially of the broadly construed ‘cultural’ nature – artistic<br />

and religious, for example – however discordant, was tolerated.” 23 We also find that rulers like<br />

Shah Abbas (1571 – 1629) made concessions to popular religion, especially in terms of<br />

Muharram ceremonies that melded sanctioned devotion with folklore. 24 In short, magic bowls<br />

found room to flourish in Safavid Persia in part because of a heterogeneous spiritual landscape<br />

and official laxity towards thaumaturgy.<br />

Diffusion across Strata: A Story of Mimesis<br />

The Cantor Center’s earthenware bowl exemplifies this prevalence of magic in Safavid<br />

Persia and coincides with aesthetic changes found on other Safavid bowls, but this artifact also<br />

challenges our understanding of how far and by what routes its material culture disseminated.<br />

20<br />

Pormann and Savage-Smith, Medieval Islamic Medicine, 153; Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 78;<br />

Savage-Smith, “Safavid Magic Bowls,” 241.<br />

21<br />

Hossein Nasr, “Religion in Safavid Persia,” Iranian Studies 7, no. 1–2 (March 1974): 272,<br />

https://doi.org/10.1080/00210867408701466.<br />

22<br />

Nasr, 272.<br />

23<br />

Andrew J. Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, Library of Middle East History (London:<br />

Bloomsbury, 2006), 8.<br />

24<br />

Jean Calmard, “Shi’i Rituals and Power II. The Consolidation of Safavid Shi’ism: Folklore and Popular Religion,”<br />

in Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, ed. C. P. Melville (London: I.B. Tauris, 1996),<br />

143.

7<br />

Like other Safavid bowls, this one does not feature exterior directions and emphasizes what are<br />

presumably suras from the Qur’an. It fits into the evolution of bowls already mapped out by<br />

Savage-Smith, but its earthenware composition and crude design betrays its creation and<br />

implementation in non-elite circles, adding another dimension to this evolution. This bowl is a<br />

testament to the possibility of cultural dialogue between circles of magically-inclined clerics who<br />

served shahs and princes, as well as religious authorities in humbler settings whose communities<br />

would not have had access to the products of guild-trained coppersmiths. To be sure, many other<br />

magic bowls made in the Islamic world were not composed of metal; one small agate Shi’i magic<br />

bowl was made in 1606 in India and several others were made of porcelain in seventeenthcentury<br />

China. 25 However, these artifacts still likely belonged to prestigious, urban circles. Our<br />

earthenware bowl’s crude design suggests that in Safavid Persia, a non-elite community attained<br />

a cultural memory of magic bowls and their use as facilitators of barakah.<br />

Two questions surface from this discovery: how did magic bowls operate in non-elite<br />

settings, and how exactly were they introduced into these settings? In regard to the former,<br />

communities that could not access Galenist physicians sometimes consulted a class of itinerant<br />

geomancers, astrologers, and prognosticators for their worldly pains. 26 It’s plausible that this<br />

bowl may have been possessed by one of these pseudo-physicians. 27 Additionally, the Safavid<br />

Empire not only attained a top-down regional diversity of spiritual practices, but also a bottomup<br />

local diversity. Hossein Nasr has suggested that alongside mujtahids (Shi’i jurists who were<br />

endorsed by the government), local leaders were chosen from and within a community to<br />

25<br />

Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 78.<br />

26<br />

Savage-Smith, “Medicine,” 953; Dols and Ibn Ridwān, Medieval Islamic Medicine: Ibn Ridwān’s Treatise “On<br />

the Prevention of Bodily Ills in Egypt,” 35–36.<br />

27<br />

Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 70–73.

8<br />

represent the “religious needs of the populace.” 28 This affirmation of local religious identity and<br />

the existence of a class of traveling pseudo-physicians begin to explain how an earthenware<br />

magic bowl like the one in the Cantor Center may have circulated.<br />

In regard to this bowl’s provenance, it’s plausible that non-elite communities informed<br />

elite circles of bowl culture and that the subaltern originated these magical practices, not the<br />

elites. This historical scheme for thinking about alternative medical practices and magic at-large<br />

is generally accepted, though barely substantiated by material evidence. Unfortunately, we don’t<br />

have enough bowls to confirm an origin point in the subaltern. However, if we consider that this<br />

bowl culture proliferated among the ruling classes of Seljuk Syria – not Persia – more than three<br />

centuries before our earthenware bowl was made, it seems probable that this specific artifact was<br />

at least partly inspired by the productions of elites. This bowl particularly appears to have been<br />

imitated off of a more prestigious metallic artifact, such as one kept in the Khalili Collection (fig.<br />

6). Both bowls present the twelve zodiacs around their exteriors, are covered in an internal script,<br />

and feature an anthropomorphized icon at their centers. In addition, it appears that imitation<br />

among these bowls was not necessarily disparaged. Some of the earliest Syrian bowls bear<br />

inscriptions that state that they were copied off of objects in royal treasuries, “implying that such<br />

an association would increase their validity and potency.” 29 Unusually, the mimicry implied in<br />

the production of these bowls did not jeopardize, but rather enhanced their potential for<br />

singularization. 30 Regardless, whether or not the producers of the earthenware bowl recognized<br />

the prestige of mimesis, their bowl closely resembles other, more prestigious objects, suggesting<br />

28<br />

Nasr, “Religion in Safavid Persia,” 276.<br />

29<br />

Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 73.<br />

30<br />

Throughout this essay I describe objects using the schema of “commodification” and “singularization” put<br />

forward by Igor Kopytoff. Igor Kopytoff, “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commodization as Process,” in The<br />

Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge University Press,<br />

1988), 64–90.

9<br />

that channels for cultural borrowing existed between the strata of Safavid society. Generally<br />

speaking, scholars have had to make cautious forays into extending their analyses of magic bowl<br />

culture to the subaltern because there is little surviving material evidence that directly supports<br />

their claims. 31 I suggest that this bowl provides a first concrete step in confirming the<br />

popularization of magic bowls beyond the upper stratum of society, and furthermore, in<br />

confirming that magic bowl culture diffused dialectically between elite and non-elite<br />

communities.<br />

Hidden Meanings: A Story of Innovation<br />

Just as a story of popularization emerges from this bowl, so too does a story of<br />

transformation. As the magic bowl operated within a different community, that community<br />

reimagined the object and gave its cultural biography a new trajectory, which we can locate on<br />

the thing itself. 32 The earthenware bowl aesthetically deviates from its more prestigious<br />

counterparts in both its emphasis on script and the type of script it displays. A typical<br />

astrological magic bowl like the sixteenth-century model in the Khalili collection (fig. 6) depicts<br />

both the twelve zodiacs and all seven classical planets – Jupiter, Venus, Mars, Mercury, Saturn,<br />

the Moon, and the Sun at center – while the earthenware artifact keeps only the zodiacs and a<br />

31<br />

Flood writes that “practices of ingesting Qur’anic texts and other efficacious matter are attested both among elite<br />

communities and popular milieus” while Savage-Smith states that “The reliance at times on astrology and magic can<br />

be seen at all levels of the society… though it is most evident among the lower strata of society, especially in rural<br />

areas.” Flood, “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity and<br />

Islam,” 481; Savage-Smith, “Medicine,” 953.<br />

32<br />

This logic of examining objects to unravel their social lives is borrowed from Arjun Appadurai: “We have to<br />

follow the things themselves, for their meanings are inscribed on their forms.” Furthermore, there is a striking<br />

parallel between the adoption of new magic bowl forms by the subaltern and the concept of “transculturation”<br />

coined by Cuban historian Fernando Ortiz. The same mechanics and schema used to explain modernity, colonialism,<br />

and creolization may be aptly implemented to discuss Islamic spiritual phenomena that crossed boundaries of<br />

prestige. Arjun Appadurai, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in The Social Life of Things:<br />

Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology (Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1988), 5.

10<br />

single, central figure, effectively making more room for the painting of script. 33 This central<br />

figure also presents remarkable artistic deviation from typical anthropomorphized depictions of<br />

the sun, especially because the heavenly body is portrayed as an elaborate woman, defined by a<br />

round face, dark hair, eyes that jut off to the side, and – crucially – a unibrow. 34 This icon bears<br />

a striking resemblance to the popular Persian symbol of khorshid khanoom (“the lady of the<br />

sun”), a modern motif that ties together themes of fertility, femininity, maternity, and solar<br />

warmth. Her unibrow reflects the cultural association between eyebrows and radiance that even<br />

Jean Chardin notes in his Voyages: “the thickest and largest Eye-brows are accounted the finest,<br />

especially when they are so large that they touch each other.” 35 Since Safavid times, khorshid<br />

khanoom had been extracted from its astrological context and gradually accepted as a traditional<br />

aesthetic for tableware (fig. 7), and the name now generally refers to a beautiful woman. 36 Sparse<br />

literature exists on khorshid khanoom and her spiritual significance, and more research into this<br />

subject may reveal even greater artistic innovation in the creation of this bowl, but for our<br />

present purposes, what is important is that the producers of this bowl prioritized script over other<br />

visuals.<br />

Remarkably, none of this script is legible in any traditional sense – the bowl is covered in<br />

pseudo-script. 37 These letters might resemble some combination of Aramaic and Pahlavi,<br />

languages that had faded out of both vernacular and writing by the early modern period, but they<br />

33<br />

Savage-Smith, “Safavid Magic Bowls,” 242.<br />

34<br />

Savage-Smith discusses another Safavid bowl with an anthropomorphized sun at its center that may have<br />

preceded the earthenware bowl. Savage-Smith, “Magic-Medicinal Bowls,” 88.<br />

35<br />

Chardin, Sir John Chardin’s Travels in Persia, 216–17.<br />

36<br />

I am indebted to my mother and grandmother, Mojgan Besharat and Mahin Eslami, for helping me explain the<br />

concept of khorshid khanoom. My mother also pointed out, to my delight, that “Khorshid Khanoom” is a famous<br />

song by the Iranian singer Ebi.<br />

37<br />

That the bowl’s designs are pseudo-script has been confirmed by three Stanford community members who<br />

generously offered their expertise: Dr. Shervin Emami, Fyza Parviz, and Abdul Omira.

11<br />

certainly do not reflect their grammar. 38 The pseudo-script could be a testament to the illiteracy<br />

of its users, but even if its creators and consumers were illiterate, they would have undoubtedly<br />

been exposed to the Arabic naskh script that pervaded Islamic society. In all likelihood, this<br />

pseudo-script is an intentional design choice which ties into broader traditions of obscuring the<br />

divine. During the medieval spread of Islam, Jewish silversmiths fashioned charms and talismans<br />

that retained pseudo-Hebraic for their Muslim clientele. 39 Some scholars have suggested that<br />

foreign texts, or at least scripts that were not immediately legible, were often treated as more<br />

spiritually potent than Arabic. 40 From a different angle, Arabic scripts like Kufic were gradually<br />

schematized, divorced more and more from legibility as they were engraved into magical<br />

objects. 41 Pseudo-scripts even appear alongside Arabic scripts like thuluth on other magic bowls,<br />

as is the case for one bowl in the British Museum (fig. 8). However, unlike most other extant<br />

bowls, our earthenware model takes the application of a pseudo-script to the extreme by offering<br />

its audience nothing but illegible letters. The isolated symbols of this bowl, utterly unlike typical<br />

Arabic, also connect to another scriptural phenomenon discussed by the Islamic scholar<br />

Annemarie Schimmel; in a handful of texts there are “unconnected letters which precede a<br />

considerable number of Koranic Suras and whose meaning is not completely clear.” 42 The<br />

indecipherability of these letters, their mystery, is precisely the source of their power because it<br />

reflects the essence of the divine. Arcane pseudo-scripts also seem to approximate the same logic<br />

38<br />

John R. Perry, “New Persian: Expansion, Standardization, and Inclusivity,” in Literacy in the Persianate World,<br />

ed. Brian Spooner and William L. Hanaway, Writing and the Social Order (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012),<br />

76, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhh4r.8.<br />

39<br />

Don Aanavi, “Devotional Writing: ‘Pseudoinscriptions’ in Islamic Art,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin<br />

26, no. 9 (May 1968): 354, https://doi.org/10.2307/3258400.<br />

40<br />

Venetia Porter, “The Use of the Arabic Script in Magic,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies,<br />

Supplement: The Development of Arabic as a Written Language, 40 (July 24, 2009): 132.<br />

41<br />

Porter, 138.<br />

42<br />

Annemarie Schimmel, Deciphering the Signs of God: A Phenomenological Approach to Islam (State University<br />

of New York Press, 1994), https://www.giffordlectures.org/lectures/deciphering-signs-god-phenomenologicalapproach-islam.

12<br />

as the ninety-nine names of God, the asma al-husna, that the faithful knew were all inferior<br />

compared to “the greatest Name of God [which] must never be revealed to the uninitiated, as<br />

someone who knows it would be able to perform heavy incantations and magic.” 43 The pseudoscript<br />

of our bowl links to common, longstanding threads of affirming divinity through mystery –<br />

a mystery that draws one in, confirms the potency of the recited sura, and reminds its audience<br />

of their minuteness in the face of an unknowable sublime. In other words, it is because the script<br />

cannot be entirely understood that the bowl itself is a powerful conduit of divine blessing.<br />

This pseudo-script, a token of the transformations that occur when an object filters into a<br />

new community, also reflexively nuances our understanding of barakah. These bowls certainly<br />

root the divine in the profane, but a pseudo-script materializes a bridge between these worlds<br />

even further. The script simultaneously appears concrete, much like passages from the Qur’an,<br />

and yet it is utterly unknowable, much like the hundredth name of God. In this single aesthetic<br />

choice, we find that barakah is facilitated not just through the tension between the sacred and the<br />

profane, but more specifically between an unknowable sacred and a graspable profane. It is a<br />

tension in epistemology, a tug-of-war between the known and the unknown, that makes this<br />

script what Flood calls the “[efficacious] word made manifest.” 44 Furthermore, Flood previously<br />

identified magic bowls as an intersection between the orthodoxy of consuming the Qur’an and<br />

the heterodoxy of thaumaturgical practices separated from their purely Prophetic contexts. In this<br />

object, we find that orthodoxy and heterodoxy redefine one another. This bowl co-opts the<br />

written word’s authenticity as a vessel of higher meaning while shedding the exactness of the<br />

Qur’an. In turn, the holy text becomes mystical, arcane, and profoundly universal. In effect, the<br />

43<br />

Schimmel.<br />

44<br />

Flood, “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in Christianity and Islam,”<br />

485.

13<br />

sanctioned holy text cannot live without the magical obscurity that makes it divine, and the<br />

magical obscurity cannot act on anything but a discourse as universal as the holy book. The<br />

orthodox cannot be divorced from the mystical.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Recovering the cultural biography of this bowl has turned into unraveling all of the<br />

dichotomies of its history and use. Between mimesis and innovation, this bowl suggests that the<br />

material culture of magic bowls spanned the social strata of Safavid society far more widely than<br />

we could have imagined, and that in spanning so widely, the magic of this bowl became<br />

innovated in a way that reflected the popular uses of mysterious script. In the end, the processes<br />

of popularization and transformation are useful categories for what may be a unified<br />

phenomenon. Perhaps the bowl proliferated so widely because it was malleable enough to<br />

transform and make one’s own, just as commodities often become commodified because they<br />

bear the potential for singularization, to borrow from Igor Kopytoff’s schema. This bowl also<br />

forces us to reckon with a dichotomy between orthodoxy and heterodoxy. At this stage, even the<br />

somewhat misinformed Jean Chardin, who declared that Safavids resorted to the “Prayers of<br />

different Religions,” decently captures the blurriness of the boundaries between conformity and<br />

heresy. 45 Like the Galenist physician Ibn Ridwān who advocated for astrology or the ruler Nur<br />

al-Din Ibn Zangi who promoted both hospitals and geomancy, this bowl relied both on the holy<br />

Qur’an and the mysticism of its script. The bowl more broadly represents Islamic medicine and<br />

spirituality as inextricably tied to codependent discourses that appear to be at odds with one<br />

another only from a distance.<br />

45<br />

Chardin, Sir John Chardin’s Travels in Persia, 185.

14<br />

Lastly, the bowl guides us to think about spiritual objects that oscillate between<br />

dichotomies of sacred and profane, known and unknown. Like the previous dualities, these pairs<br />

are also mutually informative. It is through their tension that spiritual auxiliaries like our bowl<br />

become useful and captivating tools for experiencing the sublime. It was mysterious letters that<br />

acted as a fulcrum between the supernatural and sixteenth-century life, and it was these same<br />

letters that drew me in when I first stumbled upon the artifact five hundred years later. At first, I<br />

hadn’t realized that this earthenware bowl would invite me to rediscover my own history.<br />

Whenever I would go to mosque with my father growing up, a mukhi would recite a passage of<br />

the Qur’an over a bowl of water before sprinkling that water on my face. For my father, it was<br />

the ritual of niyaz during firman, but for seven-year-old me, it was just an ordinary (and<br />

sometimes inconveniently wet) part of the ceremony, a convention that veiled a millennium of<br />

mimesis and innovation. Back then, I could feel its effect despite never being able to explain it,<br />

not so different than my first encounter with the earthenware bowl. In both the mosque and the<br />

museum, it was only watery words and hidden meanings.

15<br />

Figure 1: The earthenware bowl with “khorshid khanoom” at center, the Cantor Center.<br />

Figure 2: Side view of the earthenware bowl.

16<br />

Figure 3: Opposite view of the earthenware bowl.<br />

Figure 4: One of the earliest known magic bowls, made in 1169-70, the Metropolitan Museum.

17<br />

Figure 5: A seventeenth-century Safavid bowl with a central boss, Backman Ltd.<br />

Figure 6: A sixteenth-century Safavid bowl with the seven classical planets, Khalili Collection.

18<br />

Figure 7: A nineteenth-century Qajar platter with “khorshid khanoom” at center, the State<br />

Hermitage Museum at St. Petersburg.<br />

Figure 8: A magic bowl with Syriac pseudo-script at top-left, the British Museum.

19<br />

Primary Materials<br />

“Decorated Bowl,” terracotta, sixteenth century, accession number: 1975.56, (The Cantor Arts<br />

Center at Stanford University), Cantor Arts Center, last modified 3/17/<strong>2020</strong>, Stanford<br />

University, http://cantorcollection.stanford.edu/objects-<br />

1/info?query=Creation_Place2%3D%22sub%3A%3A272%3A%3APersia%20(now%20Iran)%2<br />

2&sort=61&page=21. Description: “16 th century, Asia, Persia (now Iran), by (primary) Artist<br />

unknown. Medium: Terracotta. Credit Line: Gift of James L. Born, M.D.” (Figures 1, 2, and 3).<br />

“Magic bowl,” Cast brass magic bowl with Thuluth and pseudo-Syriac inscriptions, N/A,<br />

OA+.2603, (The British Museum, London), reproduced in “The Use of the Arabic Script in<br />

Magic,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Supplement: The Development of<br />

Arabic as a Written Language, 40 (July 24, 2009): 134, fig. 3. (Figure 8).<br />

“Magic Bowl Dedicated to Nur al-Din Mahmud b. Zangi,” copper alloy; cast, turned, engraved,<br />

formerly filled with a white substance, MTW 1443, (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New<br />

York City), The Met Museum, accessed 3/17/<strong>2020</strong>,<br />

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/642251. (Figure 4).<br />

“Magic bowl, flat bottomed, with astrological figures,” copper alloy; cast and turned, with silver<br />

inlay, early sixteenth century, MTW 1378, (Khalili Collection, London), in Hunt for Paradise:<br />

Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1505-1576 by Jon Thompson and Sheila R. Canby, (Milan: Skira,<br />

2003), 242, no. 9.2. (Figure 6).<br />

“Tray, first third of 19 th century,” Gold; forged and painted in enamels, first third of nineteenth<br />

century, no. VZ-751, (The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg), in The Lost Treasure:<br />

Persian Art by Vladimir Lukonin and Anatoly Ivanov, (New York: Parkstone Press, 2012), 242,<br />

no. 197. (Figure 7).

20<br />

Bibliography<br />

Aanavi, Don. “Devotional Writing: ‘Pseudoinscriptions’ in Islamic Art.” The Metropolitan Museum<br />

of Art Bulletin 26, no. 9 (May 1968): 353. https://doi.org/10.2307/3258400.<br />

Appadurai, Arjun. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of<br />

Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural<br />

Anthropology. Cambridge University Press, 1988.<br />

Calmard, Jean. “Shi’I Rituals and Power II. The Consolidation of Safavid Shi’ism: Folklore and<br />

Popular Religion.” In Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, edited by<br />

C. P. Melville. London: I.B. Tauris, 1996.<br />

Chardin, John. Sir John Chardin’s Travels in Persia. Edited by Edmund Lloyd, N. M. Penzer, and<br />

Percy Sykes. London: Argonaut Press, 1927.<br />

https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.169543/2015.169543.Sir-John-Chardins-Travels-In-<br />

Persia_djvu.txt.<br />

Dols, Michael W., and Ibn Ridwān. Medieval Islamic Medicine: Ibn Ridwān’s Treatise “On the<br />

Prevention of Bodily Ills in Egypt.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.<br />

Emerson, John. “Chardin, Sir John.” In Encyclopedia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation,<br />

October 13, 2011. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chardin-sir-john.<br />

Flood, Finbarr Barry. “Bodies and Becoming: Mimesis, Mediation, and the Ingestion of the Sacred in<br />

Christianity and Islam.” In Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice, edited<br />

by Sally M. Promey, 459–93. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.<br />

Freedman, P. Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. Yale University Press, 2008.<br />

https://books.google.com/books?id=bJgLPwAACAAJ.

21<br />

Kopytoff, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commodization as Process.” In The Social Life of<br />

Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 64–90. Cambridge<br />

University Press, 1988.<br />

Nasr, Hossein. “Religion in Safavid Persia.” Iranian Studies 7, no. 1–2 (March 1974): 271–86.<br />

https://doi.org/10.1080/00210867408701466.<br />

Newman, Andrew J. “Baqir Al-Majlisī and Islamicate Medicine: Safavid Medical Theory and<br />

Practice Re-Examined.” In Society and Culture in the Early Modern Middle East: Studies on<br />

Iran in the Safavid Period. Leiden: Brill, 2003.<br />

———. Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. Library of Middle East History. London:<br />

Bloomsbury, 2006.<br />

Norton, M. Sacred Gifts, Profane, Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic<br />

World. Cornell University Press, 2008.<br />

Perry, John R. “New Persian: Expansion, Standardization, and Inclusivity.” In Literacy in the<br />

Persianate World, edited by Brian Spooner and William L. Hanaway, 70–94. Writing and the<br />

Social Order. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhh4r.8.<br />

Pormann, Peter E., and Emilie Savage-Smith. Medieval Islamic Medicine. Edinburgh: Edinburgh<br />

University Press, 2007.<br />

Porter, Venetia. “The Use of the Arabic Script in Magic.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian<br />

Studies, Supplement: The Development of Arabic as a Written Language, 40 (July 24, 2009):<br />

131–40.<br />

Savage-Smith, Emilie. “Magic-Medicinal Bowls.” In Science, Tools & Magic, Part 1, edited by Julian<br />

Raby, 12:72–105, n.d.

22<br />

———. “Safavid Magic Bowls.” In Hunt for Paradise: Court Arts of Safavid Iran, 1505–1576, 240–<br />

47. Milan: Skira, 2003.<br />

Schimmel, Annemarie. Deciphering the Signs of God: A Phenomenological Approach to Islam. State<br />

University of New York Press, 1994. https://www.giffordlectures.org/lectures/deciphering-signsgod-phenomenological-approach-islam.<br />

Spoer, H. Henry. “Arabic Magic Medicinal Bowls.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 55, no.<br />

3 (September 1935): 237. https://doi.org/10.2307/594826.<br />

Stearns, Justin. “Writing the History of the Natural Sciences in the Pre-Modern Muslim World:<br />

Historiography, Religion, and the Importance of the Early Modern Period: Natural Science in the<br />

Pre-Modern Muslim World.” History Compass 9, no. 12 (December 2011): 923–51.<br />

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00810.x.