AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 3

Welcome spring and welcome 2020! This has been a thrilling issue to put together. As the weather gets warmer and things start to bloom here in Brooklyn, we’ve been inspired to explore all that’s blooming in the worlds of music, art, fashion, design and more. This issue is dedicated to the creative process, those who are elevating, glowing up and creating fresh new concepts in a whole new decade. Photographer Seleen Saleh gives us an exclusive look at her new book, Street Culture. In our interior design section, we’re excited to take you inside the home of actor and client, Danielle Brooks. We travel to Utah with A Tribe Called Camp. And for our Sounds section we talk music with composer and flutist Nathalie Joachim.

Welcome spring and welcome 2020! This has been a thrilling issue to put together. As the weather gets warmer and things start to bloom here in Brooklyn, we’ve been inspired to explore all that’s blooming in the worlds of music, art, fashion, design and more. This issue is dedicated to the creative process, those who are elevating, glowing up and creating fresh new concepts in a whole new decade.

Photographer Seleen Saleh gives us an exclusive look at her new book, Street Culture. In our interior design section, we’re excited to take you inside the home of actor and client, Danielle Brooks. We travel to Utah with A Tribe Called Camp. And for our Sounds section we talk music with composer and flutist Nathalie Joachim.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

APHROCHIC<br />

a curated lifestyle magazine<br />

ISSUE NO. 3 \ VOLUME 1 \ SPRING 2020<br />

BEHIND THE LENS \ A PLACE TO CALL HOME \ THIS LAND IS OUR LAND<br />

APHROCHIC.COM

Welcome spring and welcome 2020! This has been a thrilling issue to put together. As the<br />

weather gets warmer and things start to bloom here in Brooklyn, we’ve been inspired to<br />

explore all that’s blooming in the worlds of music, art, fashion, design, and more. This issue<br />

is dedicated to the creative process, those who are elevating, glowing up and creating fresh<br />

new concepts in a whole new decade.<br />

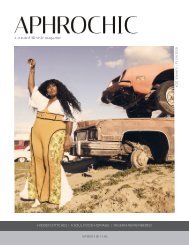

Our third cover is a celebration of street style. Photographer Seleen Saleh gives us an exclusive<br />

look at her new book, Street Culture, sharing with us a selection of beautiful photographs, including the<br />

portrait of fashion designer Sai Sankoh that’s featured on our cover.<br />

In our interior design section, we’re excited to take you inside the home of actor and client Danielle<br />

Brooks. For her first home, we created a colorful space that reflects Brooks’ sense of personal style, with<br />

color, pattern, and lots of original art. This is a house tour chock full of inspiration for your next space.<br />

Next we travel around the country and around the world, taking you on an outdoor adventure<br />

to Utah with A Tribe Called Camp. In Bedford, NY, we sit down with an inspiring group of art lovers,<br />

designers, and actors to discuss how we can all live exceptionally. Artist Andile Dyalvane takes us inside<br />

his process and his studio in South Africa. And for our Sounds section, we talk music with composer and<br />

flutist Nathalie Joachim about her new Grammy-nominated solo album dedicated to the women of Haiti.<br />

With even more art, design, and culture to explore in our third issue, we also take time to look back,<br />

exploring the roots of the African Diaspora in the history of Pan-Africanism, the New Negro Movement,<br />

and Negritude.<br />

It’s 2020, a time to celebrate new energy, new ideas, and new vision. This issue embraces that spirit,<br />

highlighting the sheer depth of creativity that’s burgeoning among Black creatives. We hope you feel as<br />

inspired as we do when you read this issue.<br />

Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Founders, <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Instagram: @aphrochic<br />

editors’ letter<br />

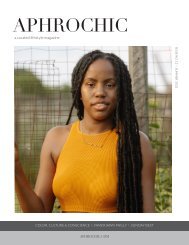

With the amazing Danielle Brooks<br />

Photo: Chinasa Cooper

SPRING 2020<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

Read This, 10<br />

Visual Cues, 12<br />

It’s a Family Affair, 14<br />

Coming Up, 22<br />

Mood, 24<br />

FEATURES<br />

Fashion // Behind the Lens, 28<br />

Interior Design // A Place to Call Home, 40<br />

Entertaining // Play Date, 58<br />

Travel // This Land Is Our Land, 76<br />

Reference // Journey to Diaspora, 92<br />

Sounds // Nathalie Joachim Gives Voicc, 98<br />

PINPOINT<br />

Artists & Artisans, 104<br />

The Remix, 112<br />

Who Are You, 116

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Cover photo: Sai Sankoh by Seleen Saleh<br />

Exclusive from Street Culture by Seleen Saleh<br />

Publishers/Editors: Jeanine Hays and Bryan Mason<br />

Creative Director: Cheminne Taylor-Smith<br />

Contact:<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Brooklyn, NY<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong>.com<br />

info@aphrochic.com<br />

Contributors:<br />

Chinasa Cooper<br />

Seleen Saleh<br />

Patrick Cline<br />

issue three 9

READ THIS<br />

There is a profound power in inspiration and in drawing guidance from those who changed history.<br />

This month’s selection of books recognizes men and women who made a difference and who continue to<br />

inspire today. The Last Negroes at Harvard is written by one of 18 African American men who were part of<br />

Harvard’s class of 1963. They changed the norms at Harvard, but each of them was also changed by their<br />

experience. Groundbreaking women of science are the focus of Changing the Equation, a look at the Black<br />

women who revolutionized the worlds of science, technology, engineering, and math. And Driving While<br />

Black reveals the freedom found on the open road and how Black travel guides helped resist oppression.<br />

The Last Negroes at Harvard.<br />

Written by Kent Garrett.<br />

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. $25<br />

Driving While Black.<br />

Written by Gretchen Sorin.<br />

Publisher: Liveright. $35<br />

Changing the Equation.<br />

Written by Tonya Bolden. Publisher:<br />

Abrams Books for Young Readers. $20<br />

10 aphrochic

VISUAL CUES<br />

New York’s High Line is a public park built on an historic elevated rail line, and includes gardens, art,<br />

food vendors, and more. Offering a unique perspective of New York City, the High Line has commissioned<br />

and produced world-class public art that offers a view of New York and its people.The Baayfalls is a new<br />

High Line Commission by artist Jordan Casteel that’s hand painted on a wall overlooking the park near<br />

22nd Street. The largest showcase of Casteel’s work, it recreates her 2017 oil painting of the same name<br />

and will be on view through December. The Baayfalls is a double portrait of Fallou—a woman Casteel<br />

befriended during her artist residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem—and Fallou’s brother, Baaye<br />

Demba Sow. The mural shows the pair outside the museum at Fallou’s table, where she sold hats that<br />

she designed. Like her other art, Casteel works from photos to create her paintings, which gives her<br />

the ability to include details that others would miss. Her vibrant, larger-than-life canvases portray the<br />

people she encounters in life, including family, friends, her students, fellow subway riders, and people<br />

she meets on the sidewalk. Learn more at thehighline.org/art/.<br />

12 aphrochic issue three 13

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

Passing It On<br />

A lot had changed for my family and for the house by the middle of the 1970s, specifically with regard to<br />

who was calling it home at that time. Aunts and uncles alike had married and moved away. And in spring<br />

of 1972, Mama passed away. When that happened, the house wasn’t sold, but instead was passed down to<br />

my grandmother, Alice Harper, beginning a line of inheritance that continues to this day.<br />

Inheritance is one of the most<br />

important building blocks of wealth in<br />

this country, and for African Americans,<br />

one of the most elusive. Currently, “inheritance<br />

… account[s] for more of the<br />

racial wealth gap than any other behavioral,<br />

demographic, or socioeconomic<br />

indicator,” according to economists,<br />

Darrick Hamilton and William Darity Jr.<br />

As a result, African American households<br />

lack access to many of the wealth-building<br />

mechanisms that make inheritance<br />

possible.<br />

Economist Janelle Jones finds that<br />

the result is, “white households inherit<br />

more money, and more often, than black<br />

households,” providing a wealth boost<br />

that, at the median, “increases wealth by<br />

more than $100,000 for white families and<br />

only $4,000 for black families”. For many<br />

Black families, including my own, one of<br />

the main ways that we have historically<br />

addressed this gap has been by purchasing<br />

and passing on homes, just like this one.<br />

When our renovation project began,<br />

these economic realities were always top<br />

of mind. Our goal was to to renovate the<br />

home so that it could last in the family<br />

for many more generations to come. My<br />

grandmother was an excellent steward of<br />

the home, and when the house came to my<br />

mother in the early 2000s, she embarked<br />

on a series of restoration projects herself.<br />

But nothing about the house had been reimagined.<br />

With my sister’s family taking<br />

residence and my nephew being the first<br />

child in the house for many years, it was<br />

time for a new vision.<br />

For me, the dining room has always<br />

felt like the center of the house. The place<br />

where we would come together for family<br />

meals and celebrations. Before I was born,<br />

many celebrations took place in that<br />

room, including my Aunt Elaine’s wedding<br />

reception in 1970. Bringing it into the 21st<br />

century meant more than just a new coat<br />

of paint. We had to recreate that feeling<br />

of togetherness. To start, plain white<br />

paint that had become old and worn was<br />

replaced with a silvery gray that catches<br />

and reflects the strong light that the room<br />

receives during the day.<br />

Antique wall sconces were replaced<br />

with modern fixtures. The dining table<br />

and chairs were all replaced as well,<br />

though we were careful to add furnishings<br />

that fit with the older feel of the space,<br />

striking a balance with the more modern<br />

wall color and lighting. And art was hung<br />

on the wall, as part of the family art collection<br />

that we’re starting.<br />

<strong>No</strong> matter how much we remodeled<br />

however, there had to be a way to<br />

THE<br />

DINING<br />

ROOM<br />

BEFORE<br />

It‘s a Family Affair is an ongoing series<br />

focusing on the history of the Black family<br />

home, stories from the Harper family,<br />

and the renovations and restorations of a<br />

house that bonds this family.<br />

Photos from Harper Family Archives<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

14 aphrochic issue three 15

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

THE DINING ROOM AFTER<br />

16 aphrochic issue three 17

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

remember those who had lived in the<br />

house before. We pulled a hutch that had<br />

belonged to Mama from the breakfast<br />

room to the dining area. An antique piece,<br />

complete with a built-in flour-sifter for<br />

making bread.<br />

Its style perfectly fitting with the new<br />

furniture, while its color - that beautiful<br />

patina of age - grounds the space and<br />

keeps it connected to the past. Even more<br />

importantly, we restored a chandelier that<br />

has hung over the dining table in that room<br />

for generations. Another beautiful antique,<br />

also purchased by Mama, we found it in<br />

the basement and cleaned each crystal<br />

by hand before restoring it to its rightful<br />

place. I later found out that cleaning the<br />

chandelier had been my mother’s traditional<br />

chore, which she did every Saturday<br />

morning as a child.<br />

The breakfast room had always been<br />

one of Mama’s favorite rooms. It was<br />

where she started her days, and often,<br />

where she ended them as well. Since then<br />

it had remained a breakfast room, even as<br />

meals became more decentralized, breakfasts<br />

became less labor intensive, and the<br />

dining room became the location for every<br />

meal. To bring the space back into utility<br />

we envisioned it with a new purpose,<br />

transforming it into a playroom for my<br />

nephew, Sebastian.<br />

Away went the bright yellow walls. We<br />

replaced them with a soft lilac, with just<br />

enough purple in the color to stay warm<br />

and inviting while highlighting the architectural<br />

details of the room. The sofa<br />

was another heirloom, donated by Aunt<br />

Elaine. Paired with a colorful, printed<br />

rug, art, and pillows that we designed, the<br />

room is now a flowing, open space. Our<br />

nephew enjoys playing there, and we enjoy<br />

watching him engage in a space that has<br />

been in the family for so many generations.<br />

As home ownership becomes ever<br />

more difficult for Black people it becomes<br />

even more important. And renovating and<br />

restoring our homes so that they can stay<br />

in the family is also of tremendous importance.<br />

It’s not simply a question of what we<br />

can make, but of what we pass on. AC<br />

THE<br />

BREAKFAST<br />

ROOM<br />

BEFORE<br />

THE BREAKFAST<br />

ROOM AFTER<br />

18 aphrochic issue three 19

IT’S A FAMILY AFFAIR<br />

IT’S NOT SIMPLY<br />

A QUESTION<br />

OF WHAT WE<br />

CAN MAKE,<br />

BUT OF WHAT<br />

WE PASS ON.<br />

20 aphrochic issue three 21

COMING UP<br />

Events, exhibits, and happenings that celebrate and explore the African Diaspora.<br />

Celebration of Black Arts<br />

July 1-31 | Philadelphia<br />

One of the oldest African American<br />

literary events in the United States, the<br />

Celebration of Black Arts is a month-long<br />

celebration of African American literature<br />

and art. Events include author readings,<br />

interactive workshops, live performances,<br />

an awards show, art exhibitions, and an<br />

outdoor festival. With attendance of over<br />

7,500, the Celebration is sponsored by Art<br />

Sanctuary of Philadelphia.<br />

For more information or for a full schedule,<br />

go to celebrationofblackwriting.org.<br />

Congregation by <strong>No</strong>rman Lewis<br />

Gullah Festival<br />

May 22-24 | Beaufort, SC<br />

The Gullah are African Americans who live in the<br />

lowcountry region of Georgia, Florida, and South<br />

Carolina. who work to preserve their African cultural<br />

heritage, including a Creole language similar to Sierra<br />

Leone’s Krio. The Gullah Festival celebrates their<br />

history and culture, showcasing crafts such as basket<br />

and cast net weaving, and includes African dance and<br />

music, drum circles, booths, and more. Learn more at<br />

originalgullahfestival.org.<br />

<strong>No</strong>rth Carolina Black Film Festival<br />

May 14-17 | Wilmington, NC<br />

In its 18th year, the <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina Black Film Festival<br />

is a four-day juried and invitational festival of independent<br />

films by Black filmmakers including features,<br />

shorts, animation, documentary films, and student<br />

films. Previous honorees and winners include Anthony<br />

Hemingway, Ava DuVernay, Giancarlo Esposito, the late<br />

Dwayne McDuffie, Scott Sanders and more. For more<br />

information or for tickets, go to blackartsalliance.org.<br />

22 aphrochic

MOOD<br />

Spring Blooms with Joyful Color Palettes<br />

Let shades of pink, coral and yellow enliven you this spring. These<br />

smile-inducing shades can be mixed or matched this season. Enjoy<br />

the whimsy of leopard print, peachy pink glassware and clothing<br />

that makes a statement in bright hues and bold patterns full of<br />

energy and joy.<br />

Bouffants & Broken Hearts, Fem<br />

Feline Bamboo Fibre Tray $24.95<br />

kitchenware.com.au<br />

Blessed ethical nail polish $15<br />

rootedwoman.com<br />

Organic Lemon, Bottled<br />

Alkaline Still Spring Water<br />

$39.99 for 24 pack<br />

shopjustwater.com<br />

Silhouette Rug, from $1500<br />

aphrochic.com<br />

Semira Off Shoulder Jumpsuit $395<br />

lemlem.com<br />

Zen-105 sunglasses $285<br />

cocoandbreezy.com<br />

Coral Peach Pink Stemware<br />

$175 for set of 6<br />

estellecoloredglass.com<br />

Turmi Pillow, Cerise $205<br />

boleroadtextiles.com<br />

Leopard Junonia basket $110<br />

indegoafrica.org Pink Kente yoga mat $89.99<br />

culturefitclothing.com<br />

24 aphrochic issue three 25

FEATURES<br />

Behind the Lens | A Place to Call Home | Play Date | This Land Is Our<br />

Land | Journey to Diaspora | Nathalie Joachim Gives Voice

Fashion<br />

Behind<br />

the Lens<br />

Seleen Saleh give us a sneak peek of<br />

her new book showcasing the beautiful<br />

diversity of street style.<br />

Photos courtesy of Seleen Saleh<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

28 aphrochic

Fashion

Fashion<br />

Seleen Saleh was just a teenager the first time she picked up a camera, and she hasn’t<br />

put it down since. “I used my first camera at 16 years old. I really loved photographs,<br />

especially black-and-whites. I wanted to see how far I could take it.” She’s taken it far, and<br />

it’s returned the favor. Seleen’s camera has taken her around the world, leading the way<br />

as she captures the spirit of fashion on the streets of New York, Paris, London, and Milan.<br />

Searching out those who organically embody its ethos, Seleen creates a visual study of<br />

culture through clothing, crafting the image one moment at a time.<br />

And her work has had an impact. Behind<br />

the lens, Seleen Saleh may be one of the most<br />

influential people in the world of street style,<br />

and you might not know her name - yet.<br />

Saleh has just published her first book,<br />

Street Culture. The work was a long time<br />

coming, but for Seleen, the moment felt right.<br />

“I really wanted to see a funky street style<br />

book,” she begins. “Something fun, colorful<br />

and exciting! My friends have been telling me<br />

for years to do one, then my coworker nudged<br />

me to do one and I obliged.”<br />

The 300-page fashion photography<br />

book is an absolute treasure trove of vibrant<br />

imagery, as well as a who’s who of the creative<br />

world. “The people I have featured in my book<br />

are amazing creatives with great style.” Saleh<br />

remarks. “I want them to be celebrated and<br />

acknowledged and embraced.” There is writer<br />

and critic Antwaun Sargent biking in a pastel<br />

sweater, model Amy Sall looking classic in a<br />

camel blazer, designer Aurora James laced<br />

up in her very own Brother Vellies, fashion<br />

and travel editor Alexander-Julian Gibbson<br />

walking down the street in a leather trench,<br />

and there are even colorful appearances by<br />

Corinne Bailey Rae and Solange.<br />

The visual world that Seleen creates has<br />

taken shape over years of work for publications<br />

such as Essence and events like AfroPunk.<br />

The images are a vital cultural record, highlighting<br />

the style and contribution of a<br />

community that is often left out of an industry<br />

that routinely looks to them for inspiration<br />

and sales.<br />

“Trends start on the street where people<br />

who don’t have access to expensive clothes get<br />

really creative in how they dress,” says Saleh.<br />

“The people on the street and some of the<br />

youth culture have always been groundbreakers<br />

with fashion and trends.”<br />

There are several photographic traditions<br />

at work in pages of Street Culture,<br />

putting Seleen’s experience as a commercial<br />

and fashion photographer on full display.<br />

Alongside these is an elevation of the unique<br />

type of environmental portraiture that’s<br />

become such an important part of the social<br />

media era. Beneath it all is a thread of photojournalism<br />

that pulls every image together.<br />

Saleh is capturing a moment in fashion, art,<br />

and style by capturing the people who are<br />

living it. Equally the work is a portrait of New<br />

York City, whose streets provide the backdrop<br />

for the portraits in this book. The journalistic<br />

element is vital to the intent of the work, Saleh<br />

maintains. Encountering people as they are<br />

rather than as a contrived ideal is the essence<br />

of street style. “Street Culture is to me a lifestyle<br />

of authenticity,” she says. “Its about your<br />

attitude, your essence and your vibe.”<br />

As a book, Street Culture is colorful,<br />

eclectic, funky, exciting, and most importantly,<br />

inclusive. “We have always been here<br />

whether you choose to acknowledge us or not.<br />

Our people have always led in style, trends and<br />

elegance. I would love my work to remind us<br />

how stunning and timeless we are. <strong>No</strong>thing<br />

can mimic the real thing.” AC<br />

Order Street Culture at bit.ly/2HQFcqU.<br />

32 aphrochic issue three 33

Fashion

Fashion<br />

36 aphrochic

Fashion<br />

issue three 39

Interior Design<br />

A Place to<br />

Call Home<br />

Danielle Brooks collaborates<br />

with <strong>AphroChic</strong> to design the<br />

celebrated actor’s first home<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

Words by <strong>AphroChic</strong>: Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

Interior Design by <strong>AphroChic</strong><br />

Styling Assistance by Heavenly Gaines

Interior Design<br />

Home is meant to be a haven - a space away from everything, reserved for family and<br />

friends and the things one values most. For actor and singer Danielle Brooks, home is<br />

a place to enjoy what she has accomplished and a place to plan for what comes next. It’s<br />

a place to rest between moments of giving it all, whether it’s on set, on stage, or in a<br />

recording booth. Most of all, it’s a place where she and her fiancé Dennis can grow from<br />

a couple into a family.<br />

issue three 43

Interior Design<br />

Danielle Brooks is a renaissance<br />

woman. An award-winning actor, Tony<br />

nominee, recording artist, and star of two<br />

Netflix series - Orange is the New Black and A<br />

Little Bit Pregnant - Brooks is known for doing<br />

it all. So when it came time to buy her first<br />

home, it was clear that the perfect place would<br />

need to have enough space to fit all of her creativity<br />

and a design that would inspire her.<br />

Brooklyn provided the first part of what<br />

she was looking for in the form of a newly<br />

renovated home with four stories and four<br />

bedrooms. With an open-plan living and<br />

dining room and several floors to walk up, it’s<br />

the kind of interior that all New Yorkers dream<br />

of having when they grow up. On top of it all is<br />

a rooftop deck, perfect for barbecues, al fresco<br />

dining and long hours spent enjoying the<br />

skyline. With the space for her home decided,<br />

Danielle turned to Brooklyn interior design<br />

firm <strong>AphroChic</strong> for the next step.<br />

“They asked the strangest questions,”<br />

Danielle smiles when asked about working<br />

with <strong>AphroChic</strong>. The home was filled with<br />

items from a previous apartment when the<br />

designers arrived a few months after the<br />

couple moved in. Deciding how to integrate<br />

what was there with what was coming was a<br />

process. For <strong>AphroChic</strong>, that process revolved<br />

around questions exploring a range of topics,<br />

from the couple’s taste in music to learning<br />

how they imagined their life evolving in the<br />

space over time. The answers helped form a<br />

design aesthetic that was uniquely their own<br />

- a reflection of Danielle’s love of music, sense<br />

of glamour, love of bold colors, and embrace of<br />

her cultural heritage.<br />

Music fuels the energy that moves<br />

throughout the home. The aural form of that<br />

energy comes from Danielle’s ever-rotating<br />

playlists. It’s a sound that mixes a little Lizzo,<br />

a little Raphael Saadiq, and some modern<br />

gospel with classic sounds like Ella Fitzgerald,<br />

Bob Marley, and of course, the best of Brooklyn’s<br />

hip-hop tradition. It’s a sound that’s<br />

warm and joyful, a perfect feeling of home.<br />

The task for <strong>AphroChic</strong>, was getting that<br />

feeling onto the walls and into the furniture.<br />

The design began with color. The<br />

strategy throughout the home was to create<br />

contrasts, blending warm and cool elements<br />

for a look that had sophistication and depth.<br />

The walls were up first. The white walls of the<br />

newly renovated townhouse lacked the soul<br />

that Danielle and Dennis required, so to start<br />

things off, the open-plan first floor was transformed<br />

with C2’s Overcast, a gray-blue shade<br />

that looks blue in the daylight, becoming a<br />

softer gray at night. The cool neutral played<br />

the perfect backdrop to an array of colorful<br />

pieces, from printed textiles, to plush furnishings,<br />

and a curated art collection.<br />

A Black-owned tech brand, Sweeten,<br />

was brought in to help with the painting and<br />

renovation. Focused on connecting homeowners<br />

with reliable contractors, they helped<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> identify the contracting crew that<br />

would assist in the home’s transformation.<br />

In addition to painting the entire first floor,<br />

they installed new lighting in the kitchen and<br />

dining room.<br />

The first floor of Danielle’s home is constructed<br />

for maximum space and flow. Completely<br />

open-plan, the kitchen floats between<br />

the twin poles of the living and dining rooms.<br />

The living room was a big point of interest, not<br />

only because it’s where Danielle and Dennis<br />

spend time relaxing together, but because it’s<br />

an integral part of one of Danielle’s favorite<br />

pastimes.<br />

“I love to host,” she beams. “I love to<br />

have people over.” From impromptu visits to<br />

holiday parties, Danielle loves for her house<br />

to be the place where people gather. Given<br />

the need for seating, one sofa just wouldn’t<br />

do. The answer was a pair of velvet sofas in<br />

emerald green from World Market. The jewel<br />

tone of the sofas mixed perfectly with the walls<br />

and the soft gray of the paired side chairs.<br />

But the real drama came from the windows.<br />

The golden silk drapery was handpicked by<br />

Danielle during a visit to The Shade Store, and<br />

quickly became the star of the room.<br />

44 aphrochic

Interior Design<br />

Across the room and past the kitchen,<br />

the dining room is home to some of the interior’s<br />

original architecture, including built-in<br />

storage and shelving. An avid reader, the<br />

actor’s collection of scripts, novels, history and<br />

cookbooks can be found throughout the home.<br />

The dining room boasts one of the home’s<br />

largest displays of Brooks’ wide-reaching enchantment<br />

with literature.<br />

On these shelves Shakespeare sits beside<br />

August Wilson, with both in the company of<br />

Oprah Winfrey, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the<br />

Blood & Bone series.<br />

Like the living room, the dining room<br />

was envisioned as an entertaining space. The<br />

smoke-black dining table and gold chandelier<br />

are the room’s centerpieces, providing<br />

light and seating for as many as eight guests.<br />

The plush, dark gray dining chairs are perfect<br />

for long nights of eating, talking, and playing<br />

games - a mainstay of Danielle’s gatherings.<br />

But also like the living room, it’s the window<br />

treatments that steal the show. The Mali Kuba<br />

print shades - another pick from the Shade<br />

Store - provided the finishing touch to the<br />

space, turning the dining room windows into a<br />

bold statement of color and pattern.<br />

Culture and heritage are the cornerstones<br />

of the design, with nods to Danielle’s<br />

South Carolina roots and Dennis’ Haitian<br />

heritage woven throughout the home. In the<br />

living room, Australian artist Brent Rosenberg’s<br />

Saint and Miss <strong>No</strong>ho prints are nods to<br />

Haitian headwrap culture. Meanwhile in the<br />

dining room, African art from Danielle’s own<br />

collection hangs on the wall. The amazingly<br />

intricate piece was a cue for bringing African-inspired<br />

textiles to the room.<br />

Up the stairs, the master bedroom is a<br />

daily retreat space. The walls were painted a<br />

deep, enveloping black, giving the bedroom a<br />

cozy and intimate feel. Artisan pieces play an<br />

48 aphrochic

Interior Design

Interior Design<br />

important role in this space as well. Pennsylvania<br />

artist Ronni Robinson created one of her<br />

signature floral fossil pieces for the couple’s<br />

home. Above the bed hang a pair of Juju hats<br />

made by hand in South Carolina - a tribute to<br />

the Juilliard-trained vocalist’s hometown. The<br />

red and white of the hats pop brightly against<br />

the chalky black walls. And beside the bed,<br />

handmade lighting from Moroccan artisans<br />

- a collaboration between <strong>AphroChic</strong> and<br />

Dounia Home - adds a finishing touch to the<br />

intimate ambiance; at night the pierced metal<br />

of the sconces throws a patterned shadow on<br />

the walls.<br />

For Danielle, finding the perfect house<br />

and creating a home is a celebration of what<br />

she’s already achieved and a preparation for<br />

what’s coming next. “Getting to buy my first<br />

home has been a joy and such an accomplishment,”<br />

she reflects. “I moved a little further out<br />

so I could really find a place that I could build<br />

a family in, and that I could share.” It was all<br />

worth it. Danielle’s home is a truly glamorous<br />

interior where her style and culture are celebrated<br />

through textiles, handmade furnishings,<br />

and art. It’s a space where Danielle and<br />

Dennis, who recently celebrated the birth<br />

of their first child, can grow and evolve as a<br />

family. Outside of its walls, Danielle’s talent will<br />

continue to attract the attention of the world.<br />

But inside the walls of her home, the world goes<br />

away, leaving the star to enjoy the people and<br />

the place that matters the most. AC<br />

52 aphrochic issue three 53

Interior Design

“Getting to buy my first home<br />

has been a joy and such<br />

an accomplishment.”

Entertaining<br />

Play<br />

Date<br />

<strong>AphroChic</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> & Thermador<br />

Hosted A Group of Creatives<br />

at the Bedford Playhouse for a<br />

Day of Living Exceptional<br />

Written and Produced<br />

by <strong>AphroChic</strong>:<br />

Jeanine Hays & Bryan Mason<br />

Photos by Chinasa Cooper<br />

58 aphrochic issue three 59

On a beautiful day, with a hint of spring in the air, a group of New York City creatives gathered<br />

at the historic Bedford Playhouse in Westchester County, NY. The goal of the gathering was<br />

simple - to celebrate artistry, the creative spirit, and community. The Bedford Playhouse was<br />

the perfect backdrop for the afternoon. Once a struggling movie theater, it was saved by a<br />

community of entertainment industry artists, many with New York City roots.<br />

Named for Clive Davis, the musical star-maker who signed<br />

everyone from Aretha Franklin and Earth Wind and Fire to Whitney<br />

Houston and Alicia Keys - as well as helping to create LaFace Records<br />

and Bad Boy - the fully renovated not-for-profit theater is known for<br />

hosting to a variety of live events, performances, and gatherings just<br />

like this one. A full roster of new and classic films are shown daily in a<br />

place where ingenuity is celebrated.<br />

On this day, guests gathered in the green room, a beautifully<br />

designed, emerald-walled suite, reserved for performers and celebrities,<br />

and sponsored in part by Thermador. On the guest list for<br />

the afternoon: actors Curtiss Cook Jr. and Mirirai Sithole; Tiana<br />

Webb Evans of the digital journal, Yard Concept; Guka Evans of<br />

The Bruknahm Project; Kalyn Chandler of Effie’s Paper with her<br />

husband Todd, a retired corporate lawyer; and design-maven Kim<br />

Myles and her husband Scott, who works for Disney.<br />

The playhouses’ executive chef, Keelin Maniscalco, prepared<br />

a menu of items sourced from the local area. Home to dozens of<br />

farms and farmers markets, the menu included an assortment of<br />

sustainable goodies, including a green goddess dressing that the<br />

chef had prepared that morning. An assortment of wines from<br />

the McBride Sisters were paired with the afternoon meal. Most<br />

popular, the Black Girl Magic rosé, chilled overnight in Thermador’s<br />

wine fridge, just one of the many items from the luxury<br />

kitchen brand that was featured in the space.<br />

As the afternoon went on, the group gathered around the<br />

table having an in-depth conversation on what it is to be a creative<br />

person in this world and live an exceptional life. Some of the<br />

questions posed: What is exceptional to you? What is exceptional<br />

about you? What makes a moment, or a day, or a life stand out as<br />

something special? What are the simple, quiet things - past what’s<br />

on your Instagram feed - that make you like no one else on earth?<br />

“It’s hard to say what’s exceptional about yourself,” remarked<br />

Tiana, “it just goes against all of the humility that’s been baked<br />

into your personality.” She continued, “Take out the idea that<br />

you have to buy something to live exceptionally, you have to wear<br />

something, you have to be something else.” Todd added, “I think<br />

the way to think about that is, What’s exceptional for you? So when<br />

you’re saying what’s exceptional to your own life, it’s not being<br />

negative with respect to anyone else’s way of living or thinking.”<br />

The conversation continued into the evening. The night<br />

ending with a clinking of glasses. <strong>No</strong>t rose-colored, but beautifully<br />

vibrant pieces handmade by artisans from the South Carolina<br />

brand, Estelle Colored Glass.<br />

In a world where everyone is so busy and distracted, it’s rare<br />

to find space to come together to recognize each other, contemplate<br />

together and have a meaningful discussion. But for one<br />

afternoon in Bedford, New York, eight creatives gathered and did<br />

just that, truly experiencing a day of living exceptionally. AC<br />

This spring view our Live Exceptional video series, in partnership with<br />

Thermador, on YouTube.com/aphrochic.<br />

issue three 61

Entertaining

Entertaining<br />

In a world where everyone<br />

is so busy, it’s rare to find<br />

space to have a meaningful<br />

conversation.<br />

64 aphrochic issue three 65

Entertaining

Entertaining<br />

72 aphrochic

Entertaining<br />

THE MENU<br />

Charcuterie platter with assorted cheeses and smoked meats<br />

Crudite with green herb dip, hummus and crispy pita<br />

Chicken fattoush salad<br />

Strawberry & almond baked brie served with fresh fruit<br />

and assorted crackers<br />

Shrimp wrapped with prosciutto<br />

Butternut squash salad<br />

Wines: Black Girl Magic Rose, Riesling, and Red Blend<br />

from the McBride Sisters<br />

issue three 75

Travel<br />

This Land<br />

Is Our Land<br />

“I’m America’s son.<br />

This is where I come from.<br />

This land is mine.”<br />

- This Land, Gary Clark, Jr.<br />

Photos supplied by A Tribe Called Camp<br />

Words by Jeanine Hays<br />

76 aphrochic

Travel

Travel<br />

Growing up in <strong>No</strong>rth Carolina, Ron Frazier has always been familiar with the outdoors. “My<br />

family and friends played outdoors all the time. We grew up on a lake and my dad was an avid<br />

fisherman and boater.” Going out in the water and playing in the nearby woods was just part<br />

of growing up for Frazier, so much so, that as an adult, his outdoor adventures turned from<br />

daylong swims to two-week excursions into some of the most remote parts of the country. From<br />

visiting the deepest parts of The Grand Canyon to the outdoor Shangri-La of Moab in Utah, the<br />

great outdoors calls to Frazier. In answering it, the childhood pastime turned part-time hobby<br />

has now developed into a brand - A Tribe Called Camp (ATCC).<br />

Frazier is nonchalant in discussing his outdoor excursions. To<br />

him, there’s nothing unusual about time spent in the deserts and<br />

forests that dot our country or in the logistics of sending a week’s<br />

worth of equipment to another state before flying out to begin a<br />

camping trip. But beneath the understated exterior is the fervor<br />

of a true enthusiast. There is a passion for nature and a love for the<br />

challenge of planning the ultimate experience, from finding the<br />

location, to mapping out the details, and even planning time for<br />

going even further off the beaten path. His getaways include eating<br />

below snow-topped peaks in Washington State, four-wheeling along<br />

a vast ocean of dunes in Oregon and trekking along the red, Mars-like<br />

landscape of the Arizona desert. But in the beginning, his outdoor<br />

quests were simply about spending time with family and keeping in<br />

touch with friends. “When we first started, A Tribe Called Camp was a<br />

way for our circle of friends to stay connected. We all like to adventure<br />

and get outdoors. The name was a way for us to share pictures of what<br />

we were doing separately and keep the crew motivated to get out.”<br />

What started as family getaways are now Instagram-worthy experiences<br />

that hundreds follow each month as ATCC trips are part of<br />

a larger community of Black outdoor enthusiasts who post content<br />

under hashtags like #outdoorafro #blackvoyageurs and #melaninbasecamp.<br />

The posts serve not only as inspiration for Black travel, but<br />

also as important statements on African Americans enjoying nature<br />

and public space. “My attitude is it’s our country, too, and the best<br />

statement you can make about your right to be in a setting is to show<br />

up. The strongest statement you can make about what’s ours or where<br />

we belong is to just show up and own that space,” says Frazier.<br />

“The Green Book was real,” remarks Frazier, as we discuss<br />

some of the historic challenges that African Americans have faced in<br />

being able to safely engage in public space in America. “The freedom<br />

to move around safely in our country wasn’t something my parents<br />

experienced.” In fact, during the Jim Crow era that Frazier’s parents<br />

grew up in, from the mid-1930s to mid-1960s, stories of Black<br />

travelers being refused service, food, lodging, and even meeting fatal<br />

consequences on the road, were all too common. Publications like<br />

The Negro Motorist Green-Book were created to help African American<br />

road-trippers navigate safely while driving around the country.<br />

Today, studies find that African Americans continue to face<br />

great challenges in accessing and enjoying public space in America.<br />

Recently, a 2016 study out of the University of Missouri found that<br />

visitors to U.S. national and state parks are disproportionately<br />

white, while the number of African Americans visitors is especially<br />

low. Many Black families reported that they don’t patronize<br />

public parks due to racist histories including incidents of violence,<br />

the exclusion of Black history from national sites, and the fact that<br />

some national parks, such as Cedar Hills State Park in Texas, occupy<br />

the land of former plantations. Looking specifically at national parks,<br />

the researcher behind the study, Kang Jae Lee observes, “Many of the<br />

80 aphrochic issue three 81

Travel

Travel<br />

adults I spoke with were raised by parents<br />

who experienced discriminatory Jim Crow<br />

laws that prevented or discouraged African<br />

Americans from visiting public parks.”<br />

Per Lee, “Park attendance in America<br />

is culturally embedded, meaning children<br />

who are raised going to parks will grow up to<br />

take their children. Many African Americans<br />

do not go to parks because their parents and<br />

grandparents could not take their children.<br />

In other words, many African Americans’<br />

lack of interest in parks or outdoor recreation<br />

is a cultural disposition shaped by<br />

centuries of racial oppression.”<br />

As he ventures out with his own family,<br />

the ongoing fact of racial discrimination<br />

is something that Frazier can’t help but<br />

be aware of. “So we’re talking generational<br />

change,” he says when asked about the<br />

differences between his experiences and<br />

those of his father. “We have not had any<br />

issues, but we try to be prepared. We do a<br />

little research on where we’re going, but you<br />

have to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.<br />

We don’t let fear lead us, but you do<br />

have to use your common sense.”<br />

For ATCC, getting outside, exploring<br />

the world around you, and doing it without<br />

apology is the mission. During a camping<br />

trip with friends, a decision was made to<br />

go to the “mecca” of outdoor life - Moab in<br />

Utah. With members of the group coming<br />

from Charlotte, Atlanta, and New York, they<br />

decided to meet up in Flagstaff, Arizona. The<br />

caravan drove off-road for 14 days to reach<br />

<strong>No</strong>rth Rim Grand Canyon and eventually<br />

Moab.<br />

During the backcountry trip, the crew<br />

explored Zion National Park, Canyonlands<br />

National Park, White Rim Road, and<br />

the Grand Staircase-Escalante National<br />

Monument. “We love Utah. It’s an amazing<br />

place and especially beautiful. You can just<br />

go and go and go and that’s an amazing experience.”<br />

During their trips, the tribe of friends<br />

and family gathers for food and fellowship<br />

around the campfire. Special care is taken to<br />

prove that roughing it doesn’t mean eating<br />

beans from a tin can. Tribe meals differ<br />

depending on the landscape.<br />

Lunch on a lakeside trip is likely to<br />

feature a fresh catch of the day with a menu<br />

of, “fire roasted red snapper with camp<br />

fire risotto, fish tacos, grilled scallops and<br />

corn.” It’s more than just getting outside,<br />

there is also reliance on the land. “I think the<br />

outdoors and nature can’t help but give you<br />

a sense of awe and wonder that broadens<br />

your perspective. Outdoors you have to take<br />

care of yourself and those around you, as<br />

well as the land. I hope these experiences<br />

teach my sons to be curious about the world<br />

and the people in it, but also confident in<br />

themselves. I like to think that our trips will<br />

expose them to a wider world and different<br />

ways of living. So as they grow into young<br />

men, they can have more choices to decide<br />

how they want to live.”<br />

Next up for ATCC is a trip this spring<br />

to the Mojave Desert and the Southwest.<br />

“These spaces are ours, too, and if the public<br />

doesn’t support them, they could be lost,”<br />

says Frazier.<br />

His message to African Americans<br />

thinking about venturing into the great<br />

outdoors is to embrace the adventure. “I<br />

think that we can enjoy these activities like<br />

anyone else, so if folks want to do it they<br />

should. I think we spread the word by doing<br />

it. Our crew made a conscious choice to not<br />

focus on asking for permission or invitations<br />

to outdoor events. We just show up like<br />

everyone else and have a good time. <strong>No</strong> permission<br />

or apologizing. Just go.” AC<br />

To learn more about A Tribe Called Camp, visit<br />

instagram.com/atribecalledcamp/.<br />

84 aphrochic

Travel<br />

“Our crew made a conscious choice<br />

to not focus on asking for<br />

permission... We just show up like<br />

everyone else and have a good time.”<br />

86 aphrochic

Camping Tips from<br />

a Tribe Called Camp<br />

PACK MULTI-PURPOSE ITEMS<br />

Think about items that can serve more than one purpose. If you bring a<br />

cup, can it also be a bowl? That will cut down on packing and weight.<br />

LAYER UP<br />

As temperatures change, layers will make it easy to dress up or down.<br />

It’s also easier to pack several small items versus one bulky item that has<br />

only one use.<br />

PACK SOCKS!<br />

They will keep your feet warm and dry. Stay away from cotton. Research<br />

the best socks for hiking to find the right pair to keep you warm.<br />

GO ANALOG<br />

Bring a paper map. Don’t rely on electronic devices for maps. If you must,<br />

make sure you download maps for the area you will be in. Cell service<br />

can be unreliable.<br />

BRING A LUXURY ITEM<br />

Pack whatever makes you happy. One thing that keeps your vibes<br />

positive. That may be a hat, a favorite candy, music, etc.<br />

PLAYLIST<br />

Lamborghini High - A$AP Mob, Juicy J<br />

Countin’ - 2 Chains<br />

Picture Me Rollin’ - Max B<br />

Money Trees - Kendrick Lamar, Jay Rock<br />

Vivid Dreams - KAYTRANADA<br />

This Land - Gary Clark Jr.<br />

Listen to the full ATCC playlist at<br />

https://spoti.fi/2xsVzZ4<br />

issue three 89

Reference<br />

Journey to Diaspora<br />

From it’s beginnings in London at the turn of the 20th century, through the first World<br />

War and the start of the New Negro Movement, Pan-Africanism became the primary<br />

descriptor under which a host of movements, philosophies and organizations were<br />

grouped and understood. By the second decade of the century, New York stood out as a<br />

beacon of Black life and a center for the emerging themes of Black culture.<br />

The city became a rallying point for<br />

talent and creativity in literature, art, music<br />

and more. Harlem in particular became the<br />

perfect environment in which to concentrate<br />

and explore the new sense of consciousness<br />

and self-possession that was growing<br />

among Black people and finding expression<br />

among the uptown creative community. The<br />

expansion of consciousness embodied in<br />

the New Negro Movement - later called The<br />

Harlem Renaissance - was both representative<br />

of and instrumental to a rising tide of internationalist<br />

activity from Black people in<br />

all corners of the world. The New Negro, the<br />

seminal 1925 anthology by Howard University<br />

professor Alain Locke, is considered the<br />

central defining text of a moment in which it<br />

seemed the whole world was coming to New<br />

York. But there is more to the story.<br />

The Harlem Renaissance can be seen<br />

as a kind of mid-point in the narrative of<br />

Pan-Africanism. It’s timing, from roughly<br />

1920 to 1930, stands between Pan-Africanism’s<br />

nascence in the discourse of 19th<br />

century orators such as Frederick Douglass<br />

and Edward Wilmot Blyden, and its eventual<br />

end, which came in the late 20th century. The<br />

Renaissance itself served as a turning point in<br />

the discourse of Black creatives and intellectuals.<br />

<strong>No</strong> longer was the conversation focused<br />

on asserting the humanity of Black people<br />

or debating the morality of their enslavement.<br />

Attention instead turned to exploring<br />

the meaning of that humanity and demonstrating<br />

the injustice of the circumstances<br />

under which it was forced to exist. The New<br />

Negro Movement, while contemporary with<br />

other group efforts of the time, occurred at<br />

a high point of international activity and collaboration<br />

among Black creatives around<br />

the world. It was instrumental in the instigation<br />

and furtherance of such thought,<br />

and with Harlem as its symbolic flagship,<br />

sparked the imaginations of those whose<br />

work would follow, including the Chicago Renaissance<br />

of the 30s and 40s which would see<br />

the rise of writer’s such as Alice Walker and<br />

Richard Wright along with a host of visual<br />

and musical artists and dance ethnographer,<br />

Katherine Dunham. As such, the Harlem Renaissance<br />

represents a moment in the history<br />

of Pan-Africanism that presaged its greatest<br />

triumphs while simultaneously charting<br />

a course towards its obsolescence and the<br />

eventual emergence of diaspora.<br />

Between Harlem and the World<br />

While the importance of New York at<br />

this time, and Harlem in particular, should<br />

not be undersold, it is important too that it<br />

not be overemphasized, at least not to the<br />

extent of ignoring the cultural and political<br />

strivings taking place elsewhere during this<br />

period. Today what is commonly referred<br />

to as the Harlem Renaissance is widely understood<br />

to have been, as Yale professor<br />

Robert Stepto puts it, “merely the <strong>No</strong>rth<br />

American component of something larger<br />

and grander.” The tendency of scholars<br />

to bristle at the specification of Harlem as<br />

the epicenter of this “larger and grander”<br />

event, isn’t new. In fact, Sterling A. Brown, a<br />

luminary professor and poet considered part<br />

of the New Negro moment, argued that “most<br />

of the writers weren’t Harlemites [and] much<br />

of the best writing was not about Harlem.”<br />

The assertion is, if not entirely inaccurate,<br />

perhaps a bit unfair. Harlem was unquestionably<br />

a special place that drew attention<br />

and talent from around the world at that time<br />

specifically because it offered opportunities<br />

for collaboration among Black intellectuals<br />

not available, or not equally available, in other<br />

parts of the United States.<br />

Though the Harlem Renaissance, as it<br />

is currently known, is not typically recognized<br />

as part of an international event, the<br />

New Negro Movement, as it was originally<br />

called, made no attempt to attach itself<br />

to a single location - particularly as Locke<br />

himself was a resident of Washington DC at<br />

the time he released his anthology. Moreover,<br />

it is difficult to believe that those involved in<br />

the actual moment believed it to be anything<br />

other than international in both composition<br />

and scope.<br />

Although primarily connected to the<br />

Harlem cultural movement, The New Negro<br />

was largely built on the contribution of authors<br />

from around the Diaspora, just as the Harlem<br />

movement itself was built upon the presence<br />

of the Diaspora in America. As scholar and<br />

author Robert Philipson points out:<br />

Prominently featured [within<br />

The New Negro] were poems by the<br />

Jamaican immigrant Claude McKay,<br />

and a short story titled The Palm Porch,<br />

by the West Indian writer Eric Walrond.<br />

Essays were contributed by Puerto Rican<br />

bibliophile Arthur Schomburg (The<br />

Negro Digs Up His Past), and by the Ja-<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public<br />

Library. “Author Langston Hughes [far left] with [left to right:] Charles S. Johnson; E. Franklin Frazier;<br />

Rudolph Fisher and Hubert T. Delaney” New York Public Library Digital Collections.<br />

Words by Bryan Mason<br />

92 aphrochic issue three 93

Reference<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black<br />

Culture, Photographs and Prints Division,<br />

The New York Public Library. “W. E. B.<br />

Dubois in the office of The Crisis.” New York<br />

Public Library Digital Collections.<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black<br />

Culture, Photographs and Prints Division,<br />

The New York Public Library. “Aimé<br />

Césaire” New York Public Library Digital<br />

Collections.<br />

maican-born journalists Joel A. Rogers<br />

(Jazz at Home) and Wilfred A. Domingo.<br />

West Indian influence was also deeply<br />

felt on the political front as well, most notably<br />

through Marcus Garvey’s UNIA movement.<br />

Yet the spirit of collaboration that animated<br />

this moment was not confined to interactions<br />

within the diaspora of the New World, it relied<br />

heavily on activities and activists in the Old<br />

World as well, with the most important of these<br />

located in the very seat of colonial power.<br />

The Two Sides of Paris<br />

If it would be unfair to strip Harlem<br />

of the notability of its position during this<br />

moment of rebirth, it would be equally so<br />

to ignore the position of Paris, New York’s<br />

sister city, in the eyes of the Black intellectuals<br />

whose movements and work carried them<br />

back and forth between these two poles of<br />

emerging Black identity. Paris was a unique<br />

place where artists, intellectuals, and transients<br />

from all corners of the Diaspora could<br />

meet and interact, often without many of the<br />

strictures that hung over them in other lands.<br />

Despite its historical appointment as<br />

one of the major sites of colonial tyranny<br />

and racist exploitation, France had become<br />

a place of unusual (though by no means<br />

absolute) tolerance through its reliance on<br />

Black soldiers and laborers during the early<br />

part of the 20th century. Brent Hays Edwards<br />

reminds us that:<br />

During World War I, about 370,000<br />

African Americans served in the segregated<br />

Army Expeditionary Force in<br />

France [while] the French conscripted<br />

nearly 620,000 soldiers from the colonies,<br />

including approximately 250,000 from<br />

Senegal and the Sudan and 30,000 from<br />

the French Caribbean. France simultaneously<br />

imported a labor force of nearly<br />

300,000, both from elsewhere in Europe<br />

and from the colonies.<br />

As a result, France emerged as a type<br />

of crossroads for the Diaspora, a theme<br />

explored often in the Black literature of<br />

the 1920s, in books such as Claude McKay’s<br />

famed Banjo: A Story Without a Plot. Paris’<br />

status as a center for world culture contributed<br />

to the growing narrative of the city<br />

in the minds of Diaspora creatives. Constructed<br />

from the endless tales of soldiers,<br />

students, and musicians, a tale emerged<br />

describing a place that was both modern<br />

and accepting, cosmopolitan and willing to<br />

embrace the changing identities of a people<br />

only just beginning to realize all that they<br />

had to offer. The draw of the city became so<br />

absolute that many of those considered to<br />

be the literary giants of Harlem’s cultural<br />

moment, including Langston Hughes, Alain<br />

Locke, Gwendolyn Bennett, Countee Cullen,<br />

and many more spent several formative<br />

years in Paris during the 1920s. International<br />

movement was so prevalent among intellectuals<br />

at this time that, as Edwards notes,<br />

“Looking just at the culture makers usually<br />

identified with the ‘Harlem Renaissance,’ it<br />

is striking that the exceptions are those who<br />

remained in the United States.”<br />

Yet despite its progressive reputation at<br />

the time, it is important to note that France<br />

in the 1920s was in no way devoid of racial<br />

tensions either between races or among<br />

the various Black populations that encountered<br />

each other there. The beneficent image<br />

of Paris that loomed so large among African<br />

Americans came at the precise moment that<br />

France was exercising the full extent of its exploitative<br />

power over its colonial holdings in<br />

Africa and the Caribbean. These contrasting<br />

views of the nation led to many schisms<br />

between African American writers and those<br />

from French-held territories. McKay in particular<br />

held his American contemporaries to<br />

account for turning what he felt was a blind<br />

eye to French oppression of Black people in<br />

its colonies. Simultaneously, however, some<br />

attention should also be paid to the senseless<br />

attitudes of a French population that would<br />

cheer the coming of Black American soldiers,<br />

offering them greater freedom and acceptance<br />

than they received in their home<br />

country, while simultaneously maintaining<br />

its right to exploit and control Black populations<br />

in other places. Still, despite its indiscretions,<br />

many Renaissance-period writers,<br />

artists, and musicians from across the<br />

Diaspora, including McCay, looked to France<br />

both as a physical location and abstract<br />

symbol of inspiration for the still developing<br />

sense of Black internationalism.<br />

L’Monde <strong>No</strong>ir<br />

Within this context, the intellectual<br />

movement of Black Paris in the 1920s was,<br />

like that of Harlem, largely contained within<br />

the myriad journals produced at the time.<br />

These not only expressed a consciousness of<br />

the interrelated issues facing Black people<br />

around the world, but also demonstrated<br />

their commitment to the internationalist<br />

approach to meeting these challenges<br />

through their affiliation with English-language<br />

journals emanating out of Harlem<br />

and elsewhere. As much as could be said of<br />

the titles of Harlem’s many publications, the<br />

names of French journals including, La Paria,<br />

L’Action coloniale, La Voix des Negres, La Race<br />

negre, La Depeche africaine, Legitime Defense,<br />

Le Revue du monde noir, Le Cri des Negres,<br />

L’Etudiant <strong>No</strong>ir, and Africa, serve as clear<br />

exposition on the concerns and attitudes<br />

of Paris’ Black intelligentsia. Bilingualism<br />

was common among publications on both<br />

sides of the Atlantic, with several American<br />

journals producing French language editions<br />

for European circulation, and many French<br />

magazines, such as La Depeche africaine,<br />

including English language sections among<br />

their standard content.<br />

The desire to see Black thought, creativity,<br />

and experience translated across linguistic<br />

boundaries inspired one of the most<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public<br />

Library. “UNIA Parade, organized in Harlem, 1920” New York Public Library Digital Collections.<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black<br />

Culture, Photographs and Prints Division,<br />

The New York Public Library. “La Revue<br />

Du Monde <strong>No</strong>ir” New York Public Library<br />

Digital Collections.<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black<br />

Culture, Photographs and Prints Division,<br />

The New York Public Library. “Franz<br />

Masereel woodcut” New York Public Library<br />

Digital Collections.<br />

94 aphrochic issue three 95

Reference<br />

important francophone figures, Jane Nardal,<br />

to reach out to Alain Locke with the intention<br />

of creating a translation of The New Negro<br />

for French-speaking audiences. A student<br />

at the time, Nardal maintained connections<br />

to several French journals, most notably,<br />

La Depeche africaine, the first issue of which<br />

featured her article L’internationalisme noir.<br />

Nardal’s proposal to Locke is in many ways an<br />

enactment of the theoretical stance taken by<br />

this article, as Nardal states in her own words:<br />

In this postwar period, the barriers<br />

that exist between countries are being<br />

lowered, or are being pulled down…<br />

Negroes of all origins and nationalities,<br />

with different customs and religions,<br />

vaguely sense that they belong in spite of<br />

everything to a single and same race…If<br />

the black wants to be himself, to affirm<br />

his personality, not to be the copy of some<br />

type of another race (as often brings<br />

him resentment and mockery)…he must<br />

profit from acquired experience, from<br />

intellectual riches, through others, but in<br />

order to better understand himself[.]<br />

The Birth of Negritude<br />

Nardal’s attempts to translate The New<br />

Negro were not successful. Nevertheless she<br />

continued to espouse a form of internationalism<br />

very close in nature to that asserted by<br />

Alain Locke. In 1931, as the stresses of the Great<br />

Depression were showing on the New Negro<br />

Movement in Harlem, Nardal partnered with<br />

her sister Paulette Nardal to bring forth their<br />

own journal, Le Revue du monde noir, a critical<br />

publication in the evolution of Black francophone<br />

intellectualism, and a starting point in<br />

the foundation of Negritude.<br />

Negritude was the predominant<br />

movement among Black francophone intellectuals<br />

of the 1930s and 40s. “In practice,”<br />

according to Emmanuel Egar, “Negritude had<br />

come into being through…Paulette and Jane<br />

Nardal, [editors of] Review of the Black World,<br />

the journal that recognized the value of Black<br />

experiences throughout the world.” Yet it would<br />

be Aime Cesaire, a Martinican, Leon Damas,<br />

from French Guyana, and Leopold Senghor<br />

of Senegal, the foremost authors and patron<br />

saints of this movement, who would give shape<br />

to this pivotal literary and cultural concept.<br />

For Senghor, Damas, and Cesaire, internationalism<br />

lay at the heart of their association.<br />

As students in Paris hailing<br />

from different ends of the French colonial<br />

empire, their association was in itself a form<br />

of Pan-African collaboration. Moreover,<br />

the movement drew clear inspiration<br />

from the work of Pan-African intellectual<br />

movements in other parts of the world. In<br />

that spirit of collaboration and unity across<br />

nations, Damas went so far as to assert that,<br />

“Negritude has been the French assertion of<br />

the New Negro Movement”.<br />

In Paris, Damas, Senghor, and Cesaire<br />

met and together founded L’Etudiant <strong>No</strong>ir.<br />

Despite descriptions as, “a thin, eightpage<br />

periodical,” that likely produced only<br />

one issue, the publication has nevertheless<br />

been afforded great importance in the development<br />

of Negritude, if only for bringing<br />

together the talents of its three brightest luminaries.<br />

Nevertheless, the formally recognized<br />

beginning of the movement came<br />

with Cesaire’s use of negritude in his epic<br />

poem, <strong>No</strong>tebook of a Return to the Native Land,<br />

published in Paris in 1939.<br />

Unlike the New Negro Movement, which<br />

is widely recognized for its social as well<br />

as its artistic impact, there has been some<br />

question around the importance of Negritude<br />

outside of its initial literary context. Considering<br />

the question in his 1966 article,<br />

Négritude: A Pan-African Ideal?, Bently<br />

Le Baron suggested that, as a movement,<br />

“Negritude has always been a literary-cultural<br />

movement, a movement more potent in<br />

the realm of intellect and idea than in terms of<br />

concrete political activity, and it might even be<br />

argued that its net effect is more detrimental<br />

than helpful to the Pan-African aim of political<br />

union on a continental scale.” Predictably, the<br />

opinions of the movement’s founders were<br />

markedly different. When questioned on the<br />

political value of a poetry-driven movement,<br />

Damas returned that, “all the revolutions on<br />

the world succeed chiefly by the message<br />

of the poets. [T]hanks to negritude you had<br />

the end of French colonialism and the independence<br />

of Africa.” Moreover, the political<br />

careers of the founders of the movement belie<br />

the suggestion that it and its proponents were<br />

apolitical, most notably in the case of Senghor,<br />

who became Senegal’s first post-colonial<br />

president.<br />

Pan-Africanism and Communism<br />

While the Negritude movement grew in<br />

power and influence throughout the francophone<br />

diaspora, in other parts of the world,<br />

work was being done that, though different<br />

in approach, nevertheless shared Negritude’s<br />

desire to cast off the chains of colonial oppression<br />

and its recognition of the commonalities<br />

of racial oppression throughout the<br />

world. In 1931, while working in Moscow as<br />

the editor of The Negro Worker – a Communist<br />

Party publication through the Negro International<br />

– George Padmore released The Life<br />

and Struggles of Negro Toilers, a comparatively<br />

brief yet comprehensive survey of the<br />

working conditions and oppression of Black<br />

people in Africa, the United States, and the<br />

Caribbean. <strong>No</strong>t surprisingly, given Padmore’s<br />

affiliation with the Communist Party at the<br />

time, the book concludes by advocating the<br />

positive role of the Red International Labor<br />

Unions (R.I.L.U.) as a radically militant opposition<br />

to both white chauvinism and the capitalist<br />

imperialism that created and sustains<br />

that distorted perspective.<br />

Despite the passion of his arguments,<br />

by 1934, Padmore had broken with the<br />

Communist Party. According to Russian<br />

history expert Roger Kanet, the separation<br />

came as a result of a realization that, “as<br />

Richard Wright has pointed out…the Kremlin<br />

was merely using Black men as political<br />

pawns to be maneuvered in Russian interests<br />

alone.” In 1937, following a move to London,<br />

Padmore became a founding member of the<br />

International African Services Bureau (IASB),<br />

a revision of an older organization – The International<br />

African Friends of Abyssinia – led<br />

by CLR James to campaign against Italian incursions<br />

into Abyssinia. In the same year, the<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints, New York Public Library.<br />

“Langston Hughes and Léon-Gontran Damas” New York Public Library Digital Collections.<br />

IASB called for the formation of a Pan-African<br />

Federation, which would provide an<br />

overarching structure for London’s many<br />

active Pan-Africanist groups. Over a period<br />

of three years, from 1937 to 1939, the organization<br />

would produce no less than three<br />

distinct publications: Africa and the World<br />

( July – September 1937), African Sentinel<br />

(October 1937 – April 1938); [and] International<br />

African Opinion ( July 1938 – March 1939).<br />

The Sixth Conference<br />

In 1945, following the Second World<br />

War, the Pan-African Federation called<br />

for a Pan-African Conference, to be held<br />

in Manchester, England in October of that<br />

year. Kanet recounts that, “Because of the<br />

problems of travel (the Second World War<br />

had just ended), the only African American<br />

present was W.E.B. DuBois, who, in recognition<br />

of his having called the previous four<br />

Congresses, chaired all the sessions except<br />

the first, which was chaired by Amy Ashwood<br />

Garvey.” Though similar to DuBois’ 1919 conference<br />

in that this, the fifth congress (or sixth<br />

conference, depending on how one prefers<br />

to count) was being held in the aftermath of<br />

a massive struggle between colonial powers,<br />

the Manchester conference was vastly<br />

different in both tenor and outcome. Instead<br />

of the mild concessions envisioned by the<br />

Versailles congress, the Manchester conference<br />

produced dramatic demands including,<br />

“‘complete and absolute independence’ for<br />

West Africa; equality for all in South Africa;<br />

federation and self-government for the<br />

British West Indies; and that ‘discrimination<br />

on account of race, creed, or colour [in Great<br />

Britian] be made a criminal offense by law’.”<br />

The 1945 congress also included the participation<br />

of Francis, later Kwame Nkrumah<br />

—the future leader of post-colonial Ghana.<br />

Nkrumah had been referred to Padmore by<br />

his childhood friend and professional collaborator<br />

CLR James. James had first made<br />

Nkrumah’s acquaintance in the United States.<br />

Nkrumah’s further involvement with organizations<br />

such as the West African Student<br />

Union and the West African Secretariat,<br />

“sharpened his vision and strengthened<br />

his commitment to freedom for the Gold<br />

Coast, West Africa, and Africa as a whole,”<br />

according to scholar, Nana Arhin Brempont.<br />

In 1957, one year after the publication of<br />

George Padmore’s seminal Pan-Africanism<br />

or Communism?, Nkrumah would fight<br />

successfully for Ghana’s independence, and<br />

Padmore would take a position as his Advisor<br />

on African Affairs. The book, which Padmore<br />

called a, “historical account of the struggles<br />

of Africans and peoples of African descent<br />

for Human Rights and Self-Determination in<br />

the modern world,” was largely a refutation<br />

of contemporary British propaganda labeling<br />

all Pan-Africanist activity as Communist. At<br />

the same time that he combated this divisive<br />

tactic, Padmore managed to provide a compelling<br />

history of Pan-African thought, while<br />

offering hope for its future.<br />

Pan-Africanism in Decline<br />

By the beginning of the 1960s, the Pan-African<br />

Congresses had, for the most part, run<br />

their course. A final congress would be held in<br />

1974 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, under the organization<br />

of Tanzania’s then president, Julius<br />

Nyerere. Much had changed in the world since<br />

a London-based, West Indian barrister first<br />

conceived of holding a meeting to give Black<br />

intellectuals with different histories yet similar<br />

heritages the opportunity to discover and<br />

reflect on the ways in which, despite distances<br />

both physical and intellectual, their futures<br />

were inextricably bound. By 1974, many African<br />

and Caribbean nations had attained independence,<br />

sparking a change in their political<br />

agendas and a redirection of focus from Black<br />

communities across the world to the needs of<br />

their own fledgling states.<br />

And though by this time the Pan-Africanist<br />

movement was fraying badly at the seams,<br />