FUSE#2

FUSE is a bi-annual publication that documents the projects at Dance Nucleus .

FUSE is a bi-annual publication that documents the projects at Dance Nucleus .

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Element#2<br />

BAHASA KOREOGRAFI<br />

Lenggang Sebagai<br />

Permulaan sebuah<br />

Penelitian dan Praktek<br />

oleh Soultari Amin Farid<br />

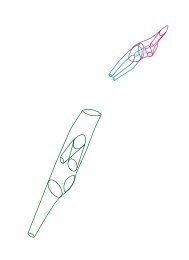

Ethnochoreolog, Mohd Anis Mohd Nor (1993) menulis,<br />

“in all types of social Malay dance the male dancer is not permitted to dance like a<br />

woman. The beauty of Malay dance posits the male dancer as the protector and<br />

supporter of the female dancer. Even though their hands don’t touch each other,<br />

the dancing couple gives the impression that there is an understanding through the<br />

execution of movement in dance. The competency of the male dancer lies in the<br />

style of mannerism that is proud and manly and does not mimic the gracefulness<br />

of the woman… The steps and wrist motions of the male dancer is enlarged with<br />

the both hands opened widely to the sides of the body and swaying as if trying to<br />

4<br />

defend his dance space from being invaded upon by his competitors” (33).<br />

Cross-dressing in performance is a common occurrence in the<br />

dance and theatre of the Malay world. Performances of kindred<br />

communities such as the ethnic communities in Java, have gender<br />

fluid examples. Ethnomusicologist, Christina Sunardi, provides a<br />

historical sampling of these performances in early Indonesia in her<br />

book, “Stunning Males and Powerful Females: Gender and<br />

Tradition in East Javanese Dance”, listing the customs of males<br />

performing female roles in Ludruk, an East Javanese popular<br />

theatre; males personating females in a 19th century Banyuwangi<br />

dance called Seblang; the tradition of males performing central<br />

Javanese female court dances from the 18th century till the 20th<br />

century; and the possibility of females performing male characters<br />

in the masked dance of Cirebon, just to name a few (20-21).<br />

I use Mohd Nor’s scholarly words to think through what it means to perform the<br />

Lenggang in holistic manner (rather than just concentration of foot movements) and<br />

at same time critiquing the form with my own embodied queer experience of<br />

enacting the Lenggang. I ask whether Mohd Nor’s description of the gender-rigid<br />

performance in social and art dance of Malay dancing provides space for someone<br />

who does not necessarily agree with the imposition of rigid gender mannerisms on<br />

the body.<br />

I may agree to the rigid gender roles when a couple dances together but in cases<br />

when a male dancer is allowed to dance solo (which is actually not a convention in<br />

Malay dance since most dances are performed collectively), should not there be<br />

concessions for the inclusions of movements which may be deemed “female”<br />

without having it be relegated as taboo? In addition, If such an act is seen as a<br />

transgression, then where do we place performance traditions which predicated on<br />

art of cross-gender performance and dressing?<br />

4<br />

“Dalam kesemua jenis tari pergaulan Melayu penari lelaki pula tidak dibolehkan menari seperti seorang wanita.<br />

Keanggunan tari Melayu telah meletakkan mertabat penari lelaki sabagai pelindung serta pendamping penari wanita.<br />

Walaupun masing-masing tangan tidak bersentuhan dengan bahagian tubuh penari saingan, kedua-kedua penari<br />

seolah-olah kelihatan bersefahaman dalam perlaksanaaan gerak dalam tari. Kejaguhan penari lelaki terletak kepada<br />

gaya kelakuan yang megah dan jantan dan tidak yang meniru keayuan gemulai wanita. … Langkah dan lengangan<br />

tangan penari lelaki sentiasa menguak dengan membuka lebar-lebar kedua tangan ke samping tubuh beserta hayunan<br />

seolah-olah mengepung ruang tarinya dari di cerebohi oleh lawan…” (33)<br />

This is definitely a complex conundrum. I bring up the issue of<br />

cross-dressing because it is an act which entails the embodying of<br />

a character/movement style of the opposite sex (male dancer<br />

embodying a female character/mannerism or female dancer<br />

embodying a male character/mannerism). Indonesia and Malaysia<br />

have produced male personalities who are known for their<br />

cross-gender and/or effeminate dance acts: Didik Nini Thowok;<br />

Rianto; and Rosnan Abdul Rahman.<br />

After the intensive residency, I had time to think about the research<br />

materials I have acquired for this investigation. I critically reflected<br />

on why I am very focus on the Lenggang, especially when in<br />

solo-dancing, it is not pertinent for me to employ the movement<br />

phrase when I am improvising. I realized soon after that I was using<br />

the Lenggang as an object of analysis to think through what it<br />

means for the Queer body to embody rigid gender<br />

roles/performance and how the nature of the Queer body may<br />

challenge these boundaries. I see the learning of the Lenggang as<br />

foundational knowledge taught to amateur dancers and in the<br />

learning of the movement phrase, the transmission process is filled<br />

with knowledge about the gender norms in the dance.<br />

65 66