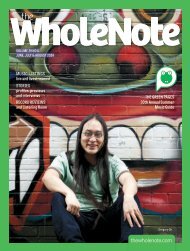

Volume 25 Issue 6 - March 2020

FEATURED: Music & Health writer Vivien Fellegi explores music, blindness & the plasticity of perception; David Jaeger digs into Gustavo Gimeno's plans for new music in his upcoming first season as music director at TSO; pianist James Rhodes, here for an early March recital, speaks his mind in a Q&A with Paul Ennis; and Lydia Perovic talks music and more with rising Turkish-Canadian mezzo Beste Kalender. Also, among our columns, Peggy Baker Dance Projects headlines Wende Bartley's In with the New; Steve Wallace's Jazz Notes rushes in definitionally where many fear to tread; ... and more.

FEATURED: Music & Health writer Vivien Fellegi explores music, blindness & the plasticity of perception; David Jaeger digs into Gustavo Gimeno's plans for new music in his upcoming first season as music director at TSO; pianist James Rhodes, here for an early March recital, speaks his mind in a Q&A with Paul Ennis; and Lydia Perovic talks music and more with rising Turkish-Canadian mezzo Beste Kalender. Also, among our columns, Peggy Baker Dance Projects headlines Wende Bartley's In with the New; Steve Wallace's Jazz Notes rushes in definitionally where many fear to tread; ... and more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Beat by Beat | Jazz Notes<br />

Notes Toward a<br />

Definition of Jazz<br />

Part One: The Forest and the Trees<br />

STEVE WALLACE<br />

It seems the longer I’m involved with jazz, the less I understand it.<br />

I’ve been immersed in it now for nearly 50 years in many ways –<br />

studying it, playing it, reading about it, collecting records, listening<br />

to it, and more recently writing about it and teaching it – and yet<br />

at times I feel I know less and less about it and would be hardpressed<br />

to offer a succinct definition of its essence. If it even has an<br />

essence anymore.<br />

Part of it is the truth of that old saw: the more you learn about a<br />

subject, the less you know about it, or so it seems. As knowledge of<br />

jazz expands, so do the boundaries; the forest keeps getting bigger to<br />

the point where you can’t see it for the trees.<br />

Perhaps this is as it should be, because jazz is not a simple music,<br />

though often at its best it seems so. But it’s quite complex, and part<br />

of the problem in trying to get a fix on what jazz actually is, is that it<br />

never stands still. It’s constantly shifting and expanding, taking on<br />

new influences while also exerting an effect on other types of music.<br />

Like many things in the digital age, this cross-pollination process has<br />

sped up in recent years, leading to a bewildering array of hybrids,<br />

which I call “hyphen-jazz”: Acid-jazz, smooth-jazz, jazz-rock, vocaljazz,<br />

Latin-jazz and so on, seemingly ad infinitum. Well, okay, these<br />

are contrived terms to describe narrow sub-genres of varying validity,<br />

but increasingly I hear people asking – and often ask myself – “Well,<br />

yeah, but what about ‘jazz-jazz’”? Does that exist anymore, and if so,<br />

then what the heck is it?<br />

A further complication, as always, is<br />

the timeline, on various levels. Firstly,<br />

jazz, being a largely improvised and spontaneous<br />

music, has always had an ephemeral,<br />

in-the-moment present. Unless it’s<br />

recorded, a jazz performance takes place<br />

in real time and then evaporates into thin<br />

air like vapour. This is one of the charms<br />

of the music, but also a source of frustration<br />

because this evanescence makes<br />

analysis, and thus understanding, difficult.<br />

But jazz is over 100 years old now<br />

and thanks to various forms of documentation<br />

– thousands of recordings, many<br />

films, books, publications and the like –<br />

it has a palpable history, an appreciable<br />

backlog of tradition and evolution, a past.<br />

Thanks to the internet, all kinds of information<br />

about jazz history is more readily<br />

available than ever before. Simply by<br />

sitting at a computer, one now has access<br />

to thousands of recordings and videos of<br />

live performances; to articles and reviews<br />

about the music; to solo transcriptions<br />

and sheet music; and to biographical<br />

information about key contributors and<br />

how they changed the music. There’s no<br />

longer any excuse for what music educators<br />

call “jazz ignorance.”<br />

But at the same time, the very nature of<br />

the internet, and the sheer vastness of the information it contains, has<br />

created a generation of (mostly) younger people with shorter attention<br />

spans than ever before, and with less curiosity about (and perhaps less<br />

appreciation for the importance of) history and the past. This will be<br />

a familiar refrain to others more or less my age, but I’m often stunned<br />

by what young jazz students – a largely hard-working, bright, talented<br />

and sincere group – don’t know about its history, and how few records<br />

some of them have listened to. There are exceptions, but some of them<br />

are completely unaware of Zoot Sims or Roy Eldridge or Ben Webster,<br />

never mind more distant figures like Sidney Bechet or Rex Stewart.<br />

On the other hand, they are much more up on contemporary figures<br />

and goings-on in the music than I am; I’m forever learning about new<br />

players and records from them, for which I’m grateful. This brings us<br />

to another wrinkle in the jazz timeline: an individual’s age and the<br />

effects the aging process can have on the perception of what jazz is.<br />

For example, I’m 63 and it’s a fact that more of my life is behind<br />

me than ahead; I have much more past than future. Throw in that I<br />

happen to have an extremely historical bent of mind and it’s small<br />

wonder that a lot of my ideas about what jazz is are rooted in its past,<br />

its history and traditions, and that I struggle to keep up with the<br />

present. Whereas many of my students and other younger players<br />

have their finger on the pulse of now, with little sense of the past or<br />

concern for history.<br />

This generational disconnect is what makes teaching challenging,<br />

but also rewarding. I get to inform young players about elements<br />

of the music’s history and then hear how they use these in their<br />

own, contemporary-minded ways. While being around young<br />

players sometimes makes me feel out of touch, it also makes me<br />

realize the value of my past experience and knowledge. These people<br />

want to learn from what older experienced players know and, if<br />

anything, being around them makes me feel less out of touch and<br />

more convinced than ever of the continuum of jazz, the connection<br />

between its past and its present. So in trying to come up with a definition,<br />

I want it to reflect not just the past or what I think jazz ought to<br />

continue to be, or what “good jazz” is, but also to be inclusive of how<br />

it’s changed and what it is now.<br />

All of these factors and others make defining jazz a daunting task,<br />

perhaps even a useless and unnecessary one. After all, Duke Ellington<br />

Duke Ellington Orchestra<br />

38 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2020</strong> thewholenote.com