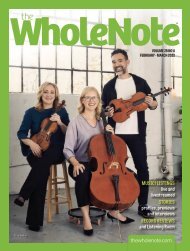

Volume 25 Issue 6 - March 2020

FEATURED: Music & Health writer Vivien Fellegi explores music, blindness & the plasticity of perception; David Jaeger digs into Gustavo Gimeno's plans for new music in his upcoming first season as music director at TSO; pianist James Rhodes, here for an early March recital, speaks his mind in a Q&A with Paul Ennis; and Lydia Perovic talks music and more with rising Turkish-Canadian mezzo Beste Kalender. Also, among our columns, Peggy Baker Dance Projects headlines Wende Bartley's In with the New; Steve Wallace's Jazz Notes rushes in definitionally where many fear to tread; ... and more.

FEATURED: Music & Health writer Vivien Fellegi explores music, blindness & the plasticity of perception; David Jaeger digs into Gustavo Gimeno's plans for new music in his upcoming first season as music director at TSO; pianist James Rhodes, here for an early March recital, speaks his mind in a Q&A with Paul Ennis; and Lydia Perovic talks music and more with rising Turkish-Canadian mezzo Beste Kalender. Also, among our columns, Peggy Baker Dance Projects headlines Wende Bartley's In with the New; Steve Wallace's Jazz Notes rushes in definitionally where many fear to tread; ... and more.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

has been a success these eight and a half years. Certain things get lost<br />

in translation … which is not always bad. But we keep working on<br />

figuring out the between-the-lines – the unsaid in the said. That took<br />

some time.”<br />

Kalender will be spending <strong>March</strong> in Alberta while preparing for<br />

the role of the Old Lady in the Joel Ivany-directed Candide at the<br />

Edmonton Opera. (“I will actually be singing the line I am so easily<br />

assimilated,” she laughs.) Back in Toronto in April, rehearsals, with<br />

the same director, begin in a very different project: Against the Grain<br />

Theatre’s final version of the Kevin Lau-composed Bound, the story<br />

of four characters in a brush with law enforcement and the arbitrary<br />

rules at border crossings. Kalender’s character is based on<br />

a true story of a professional Middle Eastern woman being asked<br />

and refusing to remove her hijab at the point of entry into France.<br />

“Border crossings is a topic we don’t talk a lot about in Canada,” she<br />

says, “and when I saw an earlier version of Bound I was grateful that<br />

these guys decided to tackle it.” Kalender became a Canadian citizen<br />

last February, and before that travelled on her Turkish passport as<br />

a Canadian permanent resident, which sometimes made things<br />

complicated. One year, on her way from Canada to Moscow via<br />

Zurich Airport for a singing gig, she was taken out of the queue and<br />

held at the airport because the airline staff in charge were not able,<br />

or willing, to verify that she did not require a work visa for Russia.<br />

When eight hours later they finally realized their mistake – thanks<br />

to a network of frantic phone calls between Turkish and Russian<br />

consular offices across two continents – she was allowed to board the<br />

next available plane to Moscow. She landed in the Russian capital at<br />

4am, and went straight to rehearsals on little or no sleep.<br />

The character she will play in Bound is held at a border for a<br />

different reason, but she and Kalender have one thing in common:<br />

their faith. Kalender is a Sufi Muslim who decided early in life that<br />

the headscarf wasn’t for her. There are countries in the world where<br />

not wearing a headscarf in public will get a woman in jail: where<br />

does she stand on this question? “Actually, when I was university-age,<br />

wearing hijabs in places like parliament and school was<br />

forbidden by law,” she says.<br />

(An aside: I pause here to remind the reader that Turkey’s path to<br />

secularization commenced after the demise of the Ottoman Empire<br />

and the end of the First World War, under Turkey’s first republican<br />

president Kemal Ataturk, and was at times more top-down than it was<br />

productive.)<br />

“But in my school, Boğaziçi University,” Kalender continues, “our<br />

professors didin’t occupy themselves with how you look. So some<br />

people would wear a hat over their scarf, for example … and the<br />

administration didn’t police clothing. But in other state universities,<br />

this rule was enforced. In today’s Turkey, it’s a matter of free choice.<br />

You can wear a hijab in school if you wish.”<br />

“In my opinion,” she says, “to order a woman to put on a scarf or<br />

to take off the scarf, they are the same thing. It means forcing your<br />

opinion on them. And it’s generally men who decide this – while I’m<br />

happy for women to be able to decide that for themselves. If it’s the<br />

government deciding for you, or members of your family, it’s coercion.”<br />

Kalender tried a hijab on for the very first time only last year<br />

– in preparation for the role in Bound. “I had a relative who wears a<br />

hijab visit me recently in Canada. One day we were talking and I told<br />

her about this role, and asked her to show me the different ways of<br />

doing a hijab. She said, ‘Beste I thought you were against it,’ and I told<br />

her, well yes, I don’t think my religion is about that. I am a religious<br />

person – but not a conservative person. I really believe in Sufism. I<br />

believe that we are all one, and that our differences are only as deep as<br />

putting on a label. I don’t believe that I necessarily need a hijab, but if<br />

that’s how you feel most comfortable, then why should I try to decide<br />

that on your behalf?”<br />

There is a lot of the Ottoman Empire in Western European opera<br />

– Ottomans held a place of fascination and fear for centuries – and<br />

I ask her what she thinks about the increased sensitivity around<br />

cultural representation in opera. She’s already sung a Fiorilla aria<br />

from Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia at a private concert, she tells me, and<br />

had fun with it, but hasn’t yet managed to see an entire traditional<br />

production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail. The rewritten<br />

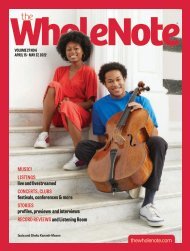

Beste Kalender, Against the Grain Theatre’s Opera Pub Night<br />

at the Amsterdam Bicycle Club, Toronto (2017)<br />

Wajdi Mouawad production at the COC from a few years back she<br />

did enjoy. “The COC took a risk, decided to adopt this new angle, and<br />

good on them. I had heard the buzz about it, that there was namaz<br />

[Islamic prayer] on stage, and all those changes in the production, and<br />

I went in and was glad that someone took this approach.” The original<br />

Entführung is fiction of course, and when it comes to the life in the<br />

Pasha’s harem not exactly accurate.“In Mozart’s opera, the ladies are<br />

in control, but in real life, they would not have been,” Kalender says.<br />

Mothers would have probably have had more influence on viziers than<br />

their harem favourites. As for the stereotypical Turco character in<br />

other operas? “When you create a character, you should endow them<br />

with a variety of features – they can’t be there just for fun and ridiculing.<br />

Something to keep in mind when reviving productions.”<br />

In Mouawad’s production, namaz is performed in Arabic. Would<br />

Ottomans have worshipped in Arabic? “Yes,” she says, and puts my<br />

pedantry to rest. “There were several languages in circulation in the<br />

Ottoman Empire, with Arabic and Farsi particularly influential. With<br />

the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the coming of Ataturk and the<br />

Turkish Republic, the official language was reformed and unified. Up<br />

to that point we were using Arabic letters; after Ataturk, we switched<br />

to Latin letters. If someone spoke to me in Ottoman today, I would not<br />

understand them.” How is the empire looked upon in today’s Turkey?<br />

Is it being fantasized about? “Yes. Certain political groups still talk<br />

about it. But I think what reignited interest in Ottomans more than<br />

anything else is this hugely popular TV show that went on for years.<br />

Magnificent Century – a quality, historically informed soap opera set<br />

in the court of Suleiman the Magnificent.” I tell her I knew about it<br />

even before Elif Batuman wrote a long piece on it in The New Yorker<br />

because the show was extremely popular in all the Slav countries in<br />

the Balkans – countries that were colonized by the Ottomans, some<br />

for several centuries. The mistrust of all things Ottoman/Turkish and<br />

the legends of heroes who fought for liberation from the empire were<br />

inbuilt in all the national poetries in the region – but this TV show,<br />

when it was on, emptied the streets. It was something akin to mania,<br />

I tell her. “It was a good show! And wasn’t Suleiman’s main woman of<br />

East European origin?”<br />

“The lady who designed tiaras for the show designed the tiara for<br />

my wedding,” Kalender says. “My big, fat Middle Eastern wedding!<br />

No, I don’t do things by halves.”<br />

Lydia Perović is an arts journalist in Toronto. Send her your<br />

art-of-song news to artofsong@thewholenote.com.<br />

DARRYL BLOCK<br />

14 | <strong>March</strong> <strong>2020</strong> thewholenote.com