B - Hobby Blues Band

B - Hobby Blues Band

B - Hobby Blues Band

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

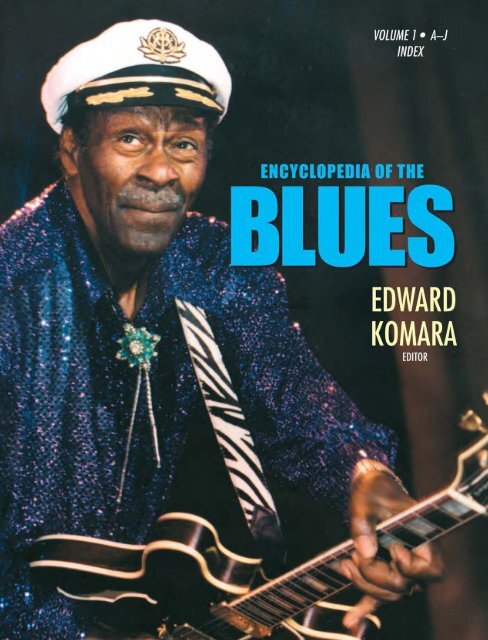

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE<br />

BLUES<br />

VOLUME 1<br />

A–J<br />

INDEX<br />

EDWARD KOMARA<br />

EDITOR<br />

New York London

Published in 2006 by<br />

Routledge<br />

Taylor & Francis Group<br />

270 Madison Avenue<br />

New York, NY 10016<br />

© 2006 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC<br />

Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group<br />

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper<br />

10987654321<br />

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-415-92699-8 (Hardcover)<br />

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-415-92699-7 (Hardcover)<br />

Library of Congress Card Number 2005044346<br />

Published in Great Britain by<br />

Routledge<br />

Taylor & Francis Group<br />

2 Park Square<br />

Milton Park, Abingdon<br />

Oxon OX14 4RN<br />

No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known<br />

or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission<br />

from the publishers.<br />

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation<br />

without intent to infringe.<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Encyclopedia of the blues / Edward Komara, editor.<br />

p. cm.<br />

Includes bibliographical references and index.<br />

ISBN 0-415-92699-8 (set : alk. paper)--ISBN 0-415-92700-5 (v. 1 : alk. paper)--ISBN 0-415-92701-3 (v. 2 : alk. paper)<br />

1. <strong>Blues</strong> (Music)--Encyclopedias. 2. <strong>Blues</strong> musicians--Biography--Dictionaries. I. Komara, Edward M., 1966-<br />

ML102.B6E53 2005<br />

781.643'03--dc22 2005044346<br />

Taylor & Francis Group is the Academic Division of T&F Informa plc.<br />

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at<br />

http://www.taylorandfrancis.com<br />

and the Routledge Web site at<br />

http://www.routledge-ny.com

ASSOCIATE EDITOR<br />

Daphne Duval Harrison<br />

University of Maryland, Baltimore County<br />

CONSULTING EDITOR<br />

Greg Johnson<br />

J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi<br />

BOARD OF ADVISERS<br />

Scott Barretta<br />

University of Mississippi<br />

Billy Branch<br />

Chicago, Illinois<br />

Samuel Floyd<br />

Center for Black Music Research<br />

Columbia College, Chicago, Illinois<br />

Bruce Iglauer<br />

Alligator Records<br />

Chicago, Illinois<br />

Yves Laberge<br />

Institut Québécois des Hautes Études Internationales<br />

Roger Misiewicz<br />

Pickering, Ontario, Canada<br />

Jim O’Neal<br />

<strong>Blues</strong>oterica<br />

Kansas City, Missouri<br />

Ann Rabson<br />

Hartwood, Virginia<br />

Richard Shurman<br />

Warrenville, Illinois<br />

Lorenzo Thomas<br />

University of Houston<br />

Billy Vera<br />

Los Angeles, California<br />

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

List of Entries A–Z ix<br />

Thematic List of Entries xxxi<br />

List of Contributors liii<br />

Introduction lix<br />

Frequently Cited Sources lxiii<br />

Entries A–Z 1<br />

Index I1<br />

vii

A<br />

ABC-Paramount/<strong>Blues</strong>way<br />

Abner, Ewart<br />

Abshire, Nathan<br />

Accordion<br />

Ace (United Kingdom)<br />

Ace (United States)<br />

Ace, Buddy<br />

Ace, Johnny<br />

Aces, The<br />

Acey, Johnny<br />

Acklin, Barbara<br />

Adams, Alberta<br />

Adams, Arthur<br />

Adams, Dr. Jo Jo<br />

Adams, Faye<br />

Adams, John Tyler ‘‘J. T.’’<br />

Adams, Johnny<br />

Adams, Marie<br />

Adams, Woodrow Wilson<br />

Adelphi Records<br />

Adins, Joris ‘‘Georges’’<br />

Admirals, The<br />

Advent Records<br />

A.F.O.<br />

Africa<br />

Agee, Raymond Clinton ‘‘Ray’’<br />

Agram <strong>Blues</strong>/Old Tramp<br />

Agwada, Vince<br />

Ajax<br />

Akers, Garfield<br />

Alabama<br />

Aladdin/Score<br />

Alert<br />

Alexander, Algernon ‘‘Texas’’<br />

Alexander, Arthur<br />

Alexander, Dave (Omar Hakim Khayyam)<br />

Alix, May<br />

Allen, Annisteen<br />

Allen, Bill ‘‘Hoss’’<br />

Allen, Lee<br />

Allen, Pete<br />

Allen, Ricky<br />

Alligator<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

ix<br />

Allison, Bernard<br />

Allison, Luther<br />

Allison, Mose<br />

Allison, Ray ‘‘Killer’’<br />

Allman Brothers <strong>Band</strong><br />

Alston, Jamie<br />

Altheimer, Joshua ‘‘Josh’’<br />

American Folk <strong>Blues</strong> Festival (AFBF)<br />

Amerson, Richard<br />

Ammons, Albert<br />

Anderson, Alvin ‘‘Little Pink’’<br />

Anderson, Bob ‘‘Little Bobby’’<br />

Anderson, Elester<br />

Anderson, Jimmy<br />

Anderson, Kip<br />

Anderson, ‘‘Little’’ Willie<br />

Anderson, Pinkney ‘‘Pink’’<br />

Animals<br />

Antone’s<br />

Apollo/Lloyds/Timely<br />

ARC (American Record Corporation)<br />

Arcenaux, Fernest<br />

Archia, Tom<br />

Archibald<br />

Archive of American Folk Song<br />

Ardoin, Alphonse ‘‘Bois Sec’’<br />

Ardoin, Amédé<br />

Arhoolie/<strong>Blues</strong> Classics/Folk Lyric<br />

Arkansas<br />

Armstrong, Howard ‘‘Louie Bluie’’<br />

Armstrong, James<br />

Armstrong, Louis<br />

Armstrong, Thomas Lee ‘‘Tom’’<br />

Arnett, Al<br />

Arnold, Billy Boy<br />

Arnold, Jerome<br />

Arnold, Kokomo<br />

Arrington, Manuel<br />

Asch/Disc/Folkways/RBF<br />

Ashford, R. T.<br />

Atlanta<br />

Atlantic/Atco/Spark<br />

Atlas<br />

AudioQuest<br />

August, Joe ‘‘Mr. Google Eyes’’<br />

August, Lynn

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Austin, Claire<br />

Austin, Jesse ‘‘Wild Bill’’<br />

Austin, Lovie<br />

B<br />

Baby Please Don’t Go/Don’t You<br />

Leave Me Here<br />

Bailey, Deford<br />

Bailey, Kid<br />

Bailey, Mildred<br />

Bailey, Ray<br />

Baker, Etta<br />

Baker, Houston<br />

Baker, LaVern<br />

Baker, Mickey<br />

Baker, Willie<br />

Baldry, ‘‘Long’’ John<br />

Ball, Marcia<br />

Ballard, Hank<br />

Ballou, Classie<br />

<strong>Band</strong>era<br />

<strong>Band</strong>s<br />

Banjo<br />

Bankhead, Tommy<br />

Banks, Chico<br />

Banks, Jerry<br />

Banks, L. V.<br />

Bankston, Dick<br />

Banner<br />

Baraka, Amiri<br />

Barbecue Bob<br />

Barbee, John Henry<br />

Barker, Blue Lu<br />

Barker, Danny<br />

Barksdale, Everett<br />

Barner, Wiley<br />

Barnes, George<br />

Barnes, Roosevelt Melvin ‘‘Booba’’<br />

Barrelhouse<br />

Bartholomew, Dave<br />

Barton, Lou Ann<br />

Bascomb, Paul<br />

Basie, Count<br />

Bass<br />

Bass, Fontella<br />

Bass, Ralph<br />

Bassett, Johnnie<br />

Bastin, Bruce<br />

Bates, Lefty<br />

Batts, Will<br />

Bayou<br />

Bea & Baby<br />

x<br />

Beacon<br />

Beaman, Lottie<br />

Bear Family<br />

Beard, Chris<br />

Beard, Joe<br />

Beasley, Jimmy<br />

Beauregard, Nathan<br />

Belfour, Robert<br />

Bell, Brenda<br />

Bell, Carey<br />

Bell, Earl<br />

Bell, Ed<br />

Bell, Jimmie<br />

Bell, Lurrie<br />

Bell, T. D.<br />

Below, Fred<br />

Below, LaMarr Chatmon<br />

Belvin, Jesse<br />

Bender, D. C.<br />

Bennet, Bobby ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Bennett, Anthony ‘‘Duster’’<br />

Bennett, Wayne T.<br />

Benoit, Tab<br />

Benson, Al<br />

Bentley, Gladys Alberta<br />

Benton, Brook<br />

Benton, Buster<br />

Bernhardt, Clyde (Edric Barron)<br />

Berry, Chuck<br />

Berry, Richard<br />

Bibb, Eric<br />

Big Bad Smitty<br />

Big Boss Man (Hi-Heel Sneakers)<br />

Big Doo Wopper<br />

Big Lucky<br />

Big Maceo<br />

Big Maybelle<br />

Big Memphis Ma Rainey<br />

Big Three Trio<br />

Big Time Sarah<br />

Big Town<br />

Big Twist<br />

Bigeou, Esther<br />

Billington, Johnnie<br />

Binder, Dennis ‘‘Long Man’’<br />

Biograph<br />

Bishop, Elvin<br />

Bizor, Billy<br />

Black & Blue/Isabel/Riverboat<br />

Black & White<br />

Black Ace<br />

Black Angel <strong>Blues</strong> (Sweet Little Angel)<br />

Black Bob<br />

Black Magic<br />

Black Newspaper Press

Black Patti<br />

Black Sacred Music<br />

Black Swan Records<br />

Black Top<br />

Blackwell, Otis<br />

Blackwell, Robert ‘‘Bumps’’<br />

Blackwell, Scrapper<br />

Blackwell, Willie ‘‘61’’<br />

Blake, Cicero<br />

Bland, Bobby ‘‘Blue’’<br />

Blanks, Birleanna<br />

Blaylock, Travis ‘‘Harmonica Slim’’<br />

Blind Blake<br />

Blind Pig<br />

Block, Rory<br />

Bloomfield, Michael<br />

Blue Horizon<br />

Blue Lake<br />

Blue, Little Joe<br />

Blue Moon (Spain)<br />

Blue Smitty<br />

Blue Suit<br />

Blue Thumb<br />

Bluebird<br />

<strong>Blues</strong><br />

<strong>Blues</strong> and Rhythm<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Ballad<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Boy Willie<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Boy’s Kingdom<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Brothers<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Connoisseur<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Folklore<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> in the Night<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Incorporated<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Project<br />

<strong>Blues</strong>breakers<br />

Bo, Eddie<br />

Bobbin<br />

Bogan, Lucille<br />

Bogan, Ted<br />

Bogart, Deanna<br />

Bohee Brothers<br />

Boines, Sylvester<br />

Boll Weavil Bill<br />

Bollin, Zuzu<br />

Bond, Graham<br />

Bonds, Son<br />

Bonner, Weldon H. Phillip ‘‘Juke Boy’’<br />

Boogie Chillen’<br />

Boogie Jake<br />

Boogie Woogie Red<br />

Book Binder, Roy<br />

Booker, Charlie (Charley)<br />

Booker, James<br />

Booze, Beatrice ‘‘Wee Bea’’<br />

Borum, ‘‘Memphis’’ Willie<br />

Bostic, Earl<br />

Boston Blackie<br />

Bouchillon, Chris<br />

Bowman, Priscilla<br />

Bowser, Erbie<br />

Boy Blue<br />

Boyack, Pat<br />

Boyd, Eddie<br />

Boyd, Louie<br />

Boykin, Brenda<br />

Boyson, Cornelius ‘‘Boysaw’’<br />

Boze, Calvin B.<br />

Bracey, Ishmon<br />

Bracken, James C.<br />

Bradford, Perry<br />

Bradshaw, Evans<br />

Bradshaw, Myron ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Braggs, Al ‘‘TNT’’<br />

Brainstorm<br />

Bramhall, Doyle<br />

Branch, William Earl ‘‘Billy’’<br />

Brandon, Skeeter<br />

Brenston, Jackie<br />

Brewer, Clarence ‘‘King Clarentz’’<br />

Brewer, Jim ‘‘Blind’’<br />

Brewster, Reverend William Herbert<br />

Bridges, Curley<br />

Brim, Grace<br />

Brim, John<br />

Brim, John Jr.<br />

Britton, Joe<br />

Broadway<br />

Brockman, Polk<br />

Bronze<br />

Brooks, ‘‘Big’’ Leon<br />

Brooks, Columbus<br />

Brooks, Hadda<br />

Brooks, Lonnie<br />

Broonzy, Big Bill<br />

Brown, Ada<br />

Brown, Andrew<br />

Brown, Arelean<br />

Brown, Bessie (Ohio)<br />

Brown, Bessie (Texas)<br />

Brown, Buster<br />

Brown, Charles<br />

Brown, Clarence ‘‘Gatemouth’’<br />

Brown, Cleo<br />

Brown, Dusty<br />

Brown, Gabriel<br />

Brown, Hash<br />

Brown, Henry ‘‘Papa’’<br />

Brown, Ida G.<br />

Brown, J. T.<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xi

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Brown, James<br />

Brown, John Henry ‘‘Bubba’’<br />

Brown, Lillyn<br />

Brown, Nappy<br />

Brown, Olive<br />

Brown, Oscar III ‘‘Bobo’’<br />

Brown, Pete<br />

Brown, Richard ‘‘Rabbit’’<br />

Brown, Roy James<br />

Brown, Ruth<br />

Brown, ‘‘Texas’’ Johnny<br />

Brown, Walter<br />

Brown, Willie Lee<br />

Brozman, Bob<br />

Brunswick<br />

Bruynoghe, Yannick<br />

Bryant, Beulah<br />

Bryant, Precious<br />

Bryant, Rusty<br />

Buchanan, Roy<br />

Buckner, Willie (Willa) Mae<br />

Buckwheat Zydeco<br />

Buford, George ‘‘Mojo’’<br />

Bull City Red<br />

Bullet<br />

Bunn, Teddy<br />

Burks, Eddie<br />

Burley, Dan<br />

Burns, Eddie<br />

Burns, Jimmy<br />

Burnside, R. L.<br />

Burnside Records<br />

Burrage, Harold<br />

Burris, J.C.<br />

Burrow, Cassell<br />

Burse, Charlie<br />

Burton, Aron<br />

Butler, George ‘‘Wild Child’’<br />

Butler, Henry<br />

Butler, Jerry<br />

Butler Twins<br />

Butterbeans and Susie<br />

Butterfield, Paul<br />

Byrd, John<br />

C<br />

Cadillac Baby<br />

Caesar, Harry ‘‘Little’’<br />

Cage, James ‘‘Butch’’<br />

Cain, Chris<br />

Cain, Perry<br />

Callender, Red<br />

xii<br />

Callicott, Joe<br />

Calloway, Cab<br />

Calloway, Harrison<br />

Cameo<br />

Campbell, ‘‘Blind’’ James<br />

Campbell, Carl<br />

Campbell, Eddie C.<br />

Campbell, John<br />

Canned Heat<br />

Cannon, Gus<br />

Cannonball Records<br />

Capitol<br />

Carbo, Hayward ‘‘Chuck’’<br />

Carbo, Leonard ‘‘Chick’’<br />

Careless Love<br />

Carmichael, James ‘‘Lucky’’<br />

Carolina Slim<br />

Caron, Danny<br />

Carr, Barbara<br />

Carr, Leroy<br />

Carr, Sam<br />

Carradine, William ‘‘Cat-Iron’’<br />

Carrier, Roy Jr. ‘‘Chubby’’<br />

Carson, Nelson<br />

Carter, Betty<br />

Carter, Bo<br />

Carter, Goree<br />

Carter, Joe<br />

Carter, Levester ‘‘Big Lucky’’<br />

Carter, Vivian<br />

Casey Jones<br />

Casey, Smith<br />

Caston, Leonard ‘‘Baby Doo’’<br />

Castro, Tommy<br />

Catfish<br />

Catfish <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Catfish Keith<br />

Cava-Tone Recording<br />

C.C. Rider<br />

Cee-Jay<br />

Celeste<br />

Cephas, John<br />

Chamblee, Edward Leon ‘‘Eddie’’<br />

Champion (Indiana)<br />

Champion (Tennessee)<br />

Chance<br />

Chandler, Gene<br />

Charity, Pernell<br />

Charles Ford <strong>Band</strong>, The<br />

Charles, Ray<br />

Charles, Rockie<br />

Charly<br />

Chart<br />

Charters, Samuel Barclay<br />

Chatmon, Sam

Chavis, Boozoo<br />

Cheatham, Jimmy and Jeannie<br />

Cheeks, Reverend Julius<br />

Chenier, C. J.<br />

Chenier, Cleveland<br />

Chenier, Clifton<br />

Chenier, Morris ‘‘Big’’<br />

Chenier, Roscoe<br />

Chess/Aristocrat/Checker/Argo/Cadet<br />

Chicago<br />

Chief/Profile/Age<br />

Chitlin Circuit<br />

Christian, Charlie<br />

Christian, Johnny ‘‘Little’’<br />

Chudd, Lewis Robert ‘‘Lew’’<br />

Church, Eugene<br />

Cincinnati<br />

C.J.<br />

Clapton, Eric<br />

Clark, ‘‘Big’’ Sam<br />

Clark, Dave<br />

Clark, Dee<br />

Clark, W. C.<br />

Clarke, William<br />

Class<br />

Classics<br />

Clay, Francis<br />

Clay, Otis<br />

Clayton, Peter Joe ‘‘Doctor’’<br />

Clayton, Willie<br />

Clearwater, Eddy<br />

Cleveland, Reverend James<br />

Clovers, The<br />

Club 51<br />

Coasters, The<br />

Cobb, Arnett<br />

Cobbs, Willie<br />

Cobra/Artistic<br />

Cohn, Larry<br />

Cole, Ann<br />

Cole, Nat King<br />

Coleman, Deborah<br />

Coleman, Gary ‘‘B. B.’’<br />

Coleman, Jaybird<br />

Coleman, Michael<br />

Coleman, Wallace<br />

Collectables<br />

Collins, Albert<br />

Collins, Little Mac<br />

Collins, Louis ‘‘Mr. Bo’’<br />

Collins, Sam<br />

Columbia<br />

Combo<br />

Conley, Charles<br />

Connor, Joanna<br />

Conqueror<br />

Convict Labor<br />

Cooder, Ry<br />

Cook, Ann<br />

Cooke, Sam<br />

Cooper, Jack L.<br />

Copeland, Johnny ‘‘Clyde’’<br />

Copeland, Shemekia<br />

Copley, Al<br />

Corley, Dewey<br />

Cosse, Ike<br />

Costello, Sean<br />

Cotten, Elizabeth<br />

Cotton, James<br />

Council, Floyd ‘‘Dipper Boy’’<br />

Coun-tree<br />

Country Music<br />

Courtney, Tom ‘‘Tomcat’’<br />

Cousin Joe<br />

Covington, Robert<br />

Cow Cow <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Cox, Ida<br />

Crafton, Harry ‘‘Fats’’<br />

Crawford, James ‘‘Sugar Boy’’<br />

Cray, Robert<br />

Crayton, Connie Curtis ‘‘Pee Wee’’<br />

Crazy Cajun Records<br />

Creach, Papa John<br />

Cream<br />

Crippen, Katie<br />

Crochet, Cleveland<br />

Crockett, G. L.<br />

Crothers, Benjamin ‘‘Scatman’’<br />

Crown<br />

Crudup, Arthur William ‘‘Big Boy’’<br />

Crump, Jesse ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Cuby and the Blizzards<br />

Curtis, James ‘‘Peck’’<br />

Cusic, Eddie<br />

D<br />

Dale, Larry<br />

Dallas, Leroy<br />

Dallas String <strong>Band</strong><br />

Dance: Artistic<br />

Dance: Audience Participation<br />

Danceland<br />

Dane, Barbara<br />

Daniels, Jack<br />

Daniels, Julius<br />

Darby, Ike ‘‘Big Ike’’<br />

Darby, Teddy<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xiii

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Darnell, Larry<br />

Davenport, Cow-Cow<br />

Davenport, Jed<br />

Davenport, Lester ‘‘Mad Dog’’<br />

Davies, Cyril<br />

Davies, Debbie<br />

Davis, ‘‘Blind’’ John<br />

Davis, Carl<br />

Davis, Cedell<br />

Davis, Eddie ‘‘Lockjaw’’<br />

Davis, Geater<br />

Davis, Guy<br />

Davis, James ‘‘Thunderbird’’<br />

Davis, Katherine<br />

Davis, Larry<br />

Davis, ‘‘Little’’ Sammy<br />

Davis, Mamie ‘‘Galore’’<br />

Davis, Maxwell<br />

Davis, ‘‘Maxwell Street’’ Jimmy<br />

Davis, Quint<br />

Davis, Reverend Gary<br />

Davis, Tiny<br />

Davis, Tyrone<br />

Davis, Walter<br />

Dawkins, James Henry ‘‘Jimmy’’<br />

Day, Bobby<br />

De Luxe/Regal<br />

Dean, Joe ‘‘Joe Dean from Bowling Green’’<br />

Decca<br />

Decca/Coral/MCA<br />

Dee, David<br />

Delafose, Geno<br />

Delafose, John<br />

Delaney, Mattie<br />

Delaney, Thomas Henry ‘‘Tom’’<br />

DeLay, Paul<br />

Delmark<br />

Derby (New York)<br />

DeSanto, Sugar Pie<br />

DeShay, James<br />

Detroit<br />

Detroit Junior<br />

Dial<br />

Dickerson, ‘‘Big’’ John<br />

Diddley, Bo<br />

Diddley Bow<br />

Dig/Ultra<br />

Dillard, Varetta<br />

Dirty Dozens<br />

Discography<br />

Dixie Hummingbirds<br />

Dixieland Jug Blowers<br />

Dixon, Floyd<br />

Dixon, Willie James<br />

Dizz, Lefty<br />

xiv<br />

Document<br />

Doggett, Bill<br />

Dollar, Johnny<br />

Dolphin, John<br />

Domino, Fats<br />

Donegan, Dorothy<br />

Dooley, Simmie<br />

DooTone/DooTo/Authentic<br />

Dorsey, Lee<br />

Dorsey, Mattie<br />

Dorsey, Thomas A.<br />

Dot Records<br />

Dotson, Jimmy ‘‘Louisiana’’<br />

Douglas, K. C.<br />

Down Home <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Doyle, Charlie ‘‘Little Buddy’’<br />

Dr. Daddy-O<br />

Dr. Hepcat<br />

Dr. John<br />

Drain, Charles<br />

Drifters<br />

Drifting <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Drummond<br />

Drums<br />

Duarte, Chris<br />

Duke<br />

Duke/Peacock/Back Beat<br />

Dukes, Laura<br />

Dunbar, Scott<br />

Duncan, Al<br />

Duncan, Little Arthur<br />

Dunn, Roy Sidney<br />

Dunson, Johnnie Mae<br />

Dupont, August ‘‘Dimes’’<br />

Dupree, Al ‘‘Big Al’’<br />

Dupree, Champion Jack<br />

Dupree, Cornell<br />

Durham, Eddie<br />

Duskin, Big Joe<br />

Dyer, Johnny<br />

E<br />

Eaglin, Snooks<br />

Ealey, Robert<br />

Earl, Ronnie<br />

Earwig<br />

Easton, Amos<br />

Easy Baby<br />

Ebony (1)<br />

Ebony (2)<br />

Eckstine, Billy

Edison<br />

Edmonds, Elga<br />

Edsel<br />

Edwards, Archie<br />

Edwards, Bernice<br />

Edwards, Chuck<br />

Edwards, Clarence<br />

Edwards, David ‘‘Honeyboy’’<br />

Edwards, Frank<br />

Edwards, ‘‘Good Rockin’’’ Charles<br />

Edwards, Willie<br />

Egan, Willie Lee<br />

El Bee (El þ Bee)<br />

El, Edward H. ‘‘Eddie’’<br />

Electric Flag<br />

Electro-Fi<br />

Elektra Records<br />

Elem, Robert ‘‘Big Mojo’’<br />

11-29<br />

Elko<br />

Ellis, Big Chief<br />

Ellis, Tinsley<br />

Embry, ‘‘Queen’’ Sylvia<br />

Emerson, William Robert ‘‘Billy the Kid’’<br />

Erby, Jack<br />

Esquerita<br />

Estes, John Adam ‘‘Sleepy John’’<br />

Evans, David Huhne, Jr.<br />

Evans, Margie<br />

Everett, Betty<br />

Evidence<br />

Excello/Nashboro<br />

Excelsior/Exclusive<br />

Ezell, Will<br />

F<br />

Fabulous Thunderbirds<br />

Fahey, John<br />

Fairfield Four<br />

Fame<br />

Fantasy/Prestige/<strong>Blues</strong>ville/Galaxy/<br />

Milestone/Riverside Record Companies<br />

Farr, Deitra<br />

Fattening Frogs for Snakes<br />

Feature<br />

Fedora<br />

Ferguson, Robert ‘‘H-Bomb’’<br />

Fiddle<br />

Field Hollers<br />

Fields, Bobby<br />

Fields, Kansas<br />

Fieldstones<br />

Fife and Drums<br />

Films<br />

Finnell, Doug<br />

Fire/Fury/Enjoy/Red Robin<br />

Five Blind Boys of Alabama<br />

Five (‘‘5’’) Royales<br />

Flash<br />

Fleetwood Mac<br />

Flemons, Wade<br />

Flerlage, Raeburn<br />

Flower, Mary<br />

Floyd, Frank ‘‘Harmonica’’<br />

Flying Fish<br />

Flynn, Billy<br />

Foddrell, Turner<br />

Foghat<br />

Foley, Sue<br />

Fontenot, Canray<br />

Ford, Clarence J.<br />

Ford, James Lewis Carter ‘‘T-Model’’<br />

Ford, Robben Lee<br />

Forehand, A. C. and ‘‘Blind’’ Mamie<br />

Formal<br />

Forms<br />

Forsyth, Guy<br />

Fortune/Hi-Q<br />

Fortune, Jesse<br />

Foster, ‘‘Baby Face’’ Leroy<br />

Foster, Little Willie<br />

Foster, Willie James<br />

Fountain, Clarence<br />

Four Brothers<br />

Fowler, T. J.<br />

Foxx, Inez and Charlie<br />

Fran, Carol<br />

Francis, David Albert ‘‘Panama’’<br />

Frank, Edward<br />

Frankie and Johnny<br />

Franklin, Guitar Pete<br />

Frankin, Reverend C. L.<br />

Frazier, Calvin<br />

Freedom/Eddie’s<br />

Freeman, Denny<br />

Freund, Steve<br />

Frisco<br />

Frog/Cygnet<br />

Frost, Frank Otis<br />

Fuller, Blind Boy<br />

Fuller, Jesse ‘‘Lone Cat’’<br />

Fuller, Johnny<br />

Fulp, Preston<br />

Fulson, Lowell<br />

Funderburgh, Anson<br />

Funk<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xv

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

G<br />

Gaddy, Bob<br />

Gaillard, Bulee ‘‘Slim’’<br />

Gaines, Earl<br />

Gaines, Grady<br />

Gaines, Roy<br />

Gaither, Bill (1)<br />

Gaither, Bill (2) ‘‘Leroy’s Buddy’’<br />

Gales Brothers<br />

Gallagher, Rory<br />

Gandy Dancers<br />

Gant, Cecil<br />

Garcia, Jerome John ‘‘Jerry’’<br />

Garibay, Randy Jr.<br />

Garland, Terry<br />

Garlow, Clarence ‘‘Bon Ton’’<br />

Garner, Larry<br />

Garon, Paul<br />

Garrett, Robert ‘‘Bud’’<br />

Garrett, Vernon<br />

Gary, Indiana<br />

Gary, Tommy<br />

Gates, Reverend James M.<br />

Gayles, Billy<br />

Gayten, Paul<br />

Geddins, Bob<br />

Gennett<br />

Georgia<br />

Geremia, Paul<br />

Giant/Gamma/Globe<br />

Gibson, Clifford<br />

Gibson, Jack<br />

Gibson, Lacy<br />

Gillum, Jazz<br />

Gilmore, Boyd<br />

Gipson, Byron ‘‘Wild Child’’<br />

Glenn, Lloyd<br />

Glover<br />

Glover, Henry<br />

Going Down Slow (I’ve Had My Fun)<br />

Gold Star<br />

Goldband Records<br />

Golden Gate Quartet<br />

Goldstein, Kenneth<br />

Goldwax<br />

Gooden, Tony<br />

Goodman, Shirley<br />

Gordon, Jay<br />

Gordon, Jimmie<br />

Gordon, Rosco(e)<br />

Gordon, Sax<br />

Gotham/20th Century<br />

Granderson, John Lee<br />

xvi<br />

Grant, Leola ‘‘Coot’’<br />

Graves, Roosevelt<br />

Gray, Arvella ‘‘Blind’’<br />

Gray, Henry<br />

Great Depression<br />

Great Migration<br />

Green, Al<br />

Green, Cal<br />

Green, Charlie<br />

Green, Clarence<br />

Green, Clarence ‘‘Candy’’<br />

Green, Grant<br />

Green, Jesse<br />

Green, Lil<br />

Green, Norman G. ‘‘Guitar Slim’’<br />

Green, Peter<br />

Greene, L. C.<br />

Greene, Rudolph Spencer ‘‘Rudy’’<br />

Greer, ‘‘Big’’ John Marshall<br />

Grey Ghost<br />

Griffin, Bessie<br />

Griffin, ‘‘Big’’ Mike<br />

Griffin, Johnny<br />

Griffin, Raymond L. ‘‘R. L.’’<br />

Griffith, Shirley<br />

Grimes, Lloyd ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Griswold, Art and Roman<br />

Grossman, Stefan<br />

Guesnon, George ‘‘Curley’’ ‘‘Creole’’<br />

Guitar<br />

Guitar Crusher<br />

Guitar Gabriel<br />

Guitar Jr.<br />

Guitar Kelley<br />

Guitar Nubbitt<br />

Guitar Shorty<br />

Guitar Slim<br />

Guitar Slim Jr.<br />

Gunter, Arthur Neal<br />

Guralnick, Peter<br />

Guthrie, Woodrow Wilson ‘‘Woody’’<br />

Guy, George ‘‘Buddy’’<br />

Guy, Phil<br />

Guy, Vernon<br />

H<br />

Haddix, Travis<br />

Hairston, ‘‘Brother’’ Will<br />

Hall, René (Joseph)<br />

Hall, Vera<br />

Hamilton, Larry<br />

Hammond, Clay

Hammond, John Henry, Jr.<br />

Hammond, John Paul<br />

Hampton, Lionel<br />

Handy, William Christopher ‘‘W. C.’’<br />

Hare, Auburn ‘‘Pat’’<br />

Harlem Hamfats<br />

Harman, James<br />

Harmograph<br />

Harmonica<br />

Harmonica Fats<br />

Harney, Richard ‘‘Hacksaw’’<br />

Harper, Joe<br />

Harpo, Slim<br />

Harrington/Clearwater Family<br />

Harris, Corey<br />

Harris, Don ‘‘Sugarcane’’<br />

Harris, Hi Tide<br />

Harris, Homer<br />

Harris, Kent L. ‘‘Boogaloo’’<br />

Harris, Peppermint<br />

Harris, Thurston<br />

Harris, Tony<br />

Harris, William ‘‘Big Foot’’<br />

Harris, Wynonie<br />

Harrison, Wilbert<br />

Hart, Alvin ‘‘Youngblood’’<br />

Hart, Hattie<br />

Harvey, Ted<br />

Hatch, Provine, Jr. ‘‘Little Hatch’’<br />

Hawkins, Ernie<br />

Hawkins, Erskine<br />

Hawkins, Screamin’ Jay<br />

Hawkins, Ted<br />

Hawkins, Walter ‘‘Buddy Boy’’<br />

Hayes, Clifford<br />

Hayes, Henry<br />

Hazell, Patrick<br />

Healey, Jeff<br />

Heartsman, Johnny<br />

Hegamin, Lucille<br />

Helfer, Erwin<br />

Hemphill, Jessie Mae<br />

Hemphill, Julius Arthur<br />

Hemphill, Sid<br />

Henderson, Bugs<br />

Henderson, Duke ‘‘Big’’<br />

Henderson, Katherine<br />

Henderson, Mike (I)<br />

Henderson, Mike (II)<br />

Henderson, Rosa<br />

Hendrix, Jimi<br />

Henry, Clarence ‘‘Frogman’’<br />

Henry, Richard ‘‘Big Boy’’<br />

Hensley, William P. ‘‘Washboard Willie’’<br />

Herald/Ember<br />

Heritage<br />

Herwin (1943 and Before)<br />

Herwin (1967 and After)<br />

Hesitation <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Hess, Chicago Bob<br />

Hi Records<br />

Hicks, Charlie<br />

Hicks, Edna<br />

Hide Away<br />

Higgins, Charles William ‘‘Chuck’’<br />

Higgins, Monk<br />

Higgs, George<br />

High Water<br />

HighTone<br />

Highways<br />

Hill, Bertha ‘‘Chippie’’<br />

Hill, Jessie<br />

Hill, Joseph ‘‘Blind Joe’’<br />

Hill, King Solomon<br />

Hill, Michael<br />

Hill, Raymond<br />

Hill, Rosa Lee<br />

Hill, Z. Z.<br />

Hillery, Mabel<br />

Hinton, Algia Mae<br />

Hinton, Edward Craig ‘‘Eddie’’<br />

Hispanic Influences on the <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Historiography<br />

Hite, Les<br />

Hite, Mattie<br />

Hoeke, Rob<br />

Hogan, Silas<br />

Hogg, John<br />

Hogg, Smokey<br />

Holder, Ace<br />

Hole, Dave<br />

Holeman, John Dee<br />

Holiday, Billie<br />

Hollimon, Clarence<br />

Hollins, Tony<br />

Holloway, Red<br />

Hollywood Fats<br />

Holmes Brothers<br />

Holmes, Wright<br />

Holmstrom, Rick<br />

Holt, Nick<br />

Holts, Roosevelt<br />

Home Cooking<br />

Homesick James<br />

Hoochie Coochie Man<br />

Hoodoo<br />

Hooker, Earl Zebedee<br />

Hooker, John Lee<br />

Hopkins, Joel<br />

Hopkins, Linda<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xvii

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Hopkins, Sam ‘‘Lightnin’’’<br />

Hornbuckle, Linda<br />

Horton, Big Walter<br />

House, Eddie ‘‘Son’’<br />

House of <strong>Blues</strong> Records<br />

House-Rent Parties<br />

Houston, Edward Wilson ‘‘Bee’’<br />

Houston Guitar Slim<br />

Houston, Joe (Joseph Abraham)<br />

Hovington, Franklin ‘‘Frank’’<br />

How Long How Long (Sitting<br />

on Top of the World)<br />

Howard, Camille<br />

Howard, Rosetta<br />

Howell, Joshua Barnes ‘‘Peg Leg’’<br />

Howlin’ Wolf<br />

Huff, Luther and Percy<br />

Hughes, Joe ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Humes, Helen<br />

Hummel, Mark<br />

Humor<br />

Hunt, Daniel Augusta ‘‘D. A.’’<br />

Hunt, Otis ‘‘Sleepy’’<br />

Hunt, Van Zula Carter<br />

Hunter, Alberta<br />

Hunter, Ivory Joe<br />

Hunter, Long John<br />

Hurt, John Smith ‘‘Mississippi John’’<br />

Hutto, Joseph Benjamin ‘‘J.B.’’<br />

Hy-Tone<br />

I<br />

I Believe I’ll Make a Change (Dust My Broom)<br />

I Just Want to Make Love to You<br />

Ichiban Records<br />

I’m a Man (Mannish Boy)<br />

I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town<br />

Imperial<br />

Instant<br />

Irma<br />

Ironing Board Sam<br />

Ivory Records<br />

J<br />

Jackson, Armand ‘‘Jump’’<br />

Jackson, Benjamin Clarence ‘‘Bullmoose’’<br />

Jackson, Bill<br />

Jackson, Bo Weavil<br />

Jackson Brothers<br />

xviii<br />

Jackson, Calvin (1)<br />

Jackson, Calvin (2)<br />

Jackson, Charles ‘‘Papa Charlie’’<br />

Jackson, Cordell ‘‘Guitar Granny’’<br />

Jackson, Fruteland<br />

Jackson, George Henry<br />

Jackson, Grady ‘‘Fats’’<br />

Jackson, Jim<br />

Jackson, John<br />

Jackson, Lee<br />

Jackson, Lil’ Son<br />

Jackson, Little Willie<br />

Jackson, Mahalia<br />

Jackson, Vasti<br />

Jackson, Willis ‘‘Gator’’ ‘‘Gator Tail’’<br />

Jacque, Beau<br />

Jacquet, Illinois<br />

James, Clifton<br />

James, Elmore<br />

James, Etta<br />

James, Jesse<br />

James, Nehemiah ‘‘Skip’’<br />

James, Steve<br />

Japan<br />

Jarrett, James ‘‘Pigmeat’’<br />

Jarrett, Theodore ‘‘Ted’’<br />

Jaxon, Frankie ‘‘Half Pint’’<br />

Jaxyson<br />

Jazz<br />

Jefferson, Blind Lemon<br />

Jefferson, Bonnie<br />

Jeffrey, Robert Ernest Lee ‘‘Bob’’<br />

JEMF (John Edwards Memorial Foundation)<br />

Jenkins, Bobo<br />

Jenkins, Duke<br />

Jenkins, Gus<br />

Jenkins, Johnny<br />

Jesus Is a Dying Bed Maker (In<br />

My Time of Dying)<br />

Jewel/Paula/Ronn<br />

JOB (J.O.B.)<br />

Joe Davis/Davis/Beacon<br />

John Henry<br />

John, Little Willie<br />

Johnny Nocturne <strong>Band</strong><br />

Johnson, Alvin Lee<br />

Johnson, Al ‘‘Snuff’’<br />

Johnson, Big Jack<br />

Johnson, Blind Willie<br />

Johnson, Buddy<br />

Johnson, Conrad<br />

Johnson, Earnest ‘‘44 Flunkey’’<br />

Johnson, Edith North<br />

Johnson, Ernie

Johnson, Henry ‘‘Rufe’’<br />

Johnson, Herman E.<br />

Johnson, James Price<br />

Johnson, James ‘‘Steady Roll’’<br />

Johnson, James ‘‘Stump’’<br />

Johnson, Joe<br />

Johnson, Johnnie<br />

Johnson, L. V.<br />

Johnson, Larry<br />

Johnson, Lemuel Charles ‘‘Lem’’<br />

Johnson, Lonnie<br />

Johnson, Louise<br />

Johnson, Luther ‘‘Georgia Boy’’ ‘‘Snake’’<br />

Johnson, Luther ‘‘Houserocker’’<br />

Johnson, Margaret<br />

Johnson, Mary<br />

Johnson, Pete<br />

Johnson, Plas<br />

Johnson, Robert Leroy<br />

Johnson, Syl<br />

Johnson, Tommy<br />

Johnson, Wallace<br />

Johnson, Willie Lee<br />

Joliet<br />

Jones, Albennie<br />

Jones, Andrew ‘‘Junior Boy’’<br />

Jones, Bessie<br />

Jones, Birmingham<br />

Jones, Calvin ‘‘Fuzzy’’<br />

Jones, Carl<br />

Jones, Casey<br />

Jones, Clarence M.<br />

Jones, Curtis<br />

Jones, Dennis ‘‘Little Hat’’<br />

Jones, Eddie ‘‘One-String’’<br />

Jones, Floyd<br />

Jones, James ‘‘Middle Walter’’<br />

Jones, Joe<br />

Jones, ‘‘Little’’ Johnny<br />

Jones, Little Sonny<br />

Jones, Maggie<br />

Jones, Max<br />

Jones, Moody<br />

Jones, Paul ‘‘Wine’’<br />

Jones, Tutu<br />

Jones, Willie<br />

Joplin, Janis<br />

Jordan, Charley<br />

Jordan, Louis<br />

Jordan, Luke<br />

JSP<br />

Jubilee/Josie/It’s a Natural<br />

Jug<br />

Juke Joints<br />

JVB<br />

K<br />

Kane, Candye<br />

Kansas City<br />

Kansas City Red<br />

Kaplan, Fred<br />

Katz, Bruce<br />

Kazoo<br />

K-Doe, Ernie<br />

Keb’ Mo’<br />

Kellum, Alphonso ‘‘Country’’<br />

Kelly, Jo Ann<br />

Kelly, Paul<br />

Kelly, Vance<br />

Kelton, Robert ‘‘Bob’’<br />

Kemble, Will Ed<br />

Kennedy, Jesse ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Kenner, Chris<br />

Kent, Willie<br />

Key to the Highway<br />

Keynote<br />

Kid Stormy Weather<br />

Killing Floor (The Lemon Song)<br />

Kimbrough, David, Jr.<br />

Kimbrough, Junior<br />

Kimbrough, Lottie<br />

King, Al<br />

King, Albert<br />

King, Bnois<br />

King, Bobby<br />

King, Chris Thomas<br />

King Curtis<br />

King, Earl<br />

King, Eddie<br />

King Ernest<br />

King/Federal/Queen<br />

King, Freddie<br />

King, ‘‘Little’’ Jimmy<br />

King, Riley B. ‘‘B. B.’’<br />

King, Saunders<br />

King Snake<br />

Kinsey, Lester ‘‘Big Daddy’’<br />

Kinsey Report<br />

Kirk, Andrew Dewey ‘‘Andy’’<br />

Kirkland, Eddie<br />

Kirkland, Leroy<br />

Kirkpatrick, Bob<br />

Kittrell, Christine<br />

Kizart, Lee<br />

Kizart, Willie<br />

K.O.B. (Kings of The <strong>Blues</strong>)<br />

Koda, Michael ‘‘Cub’’<br />

Koerner, Ray & Glover<br />

Kokomo<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xix

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Kolax, King<br />

Korner, Alexis<br />

Kubek, Smokin’ Joe<br />

L<br />

L þ R<br />

Lacey, Rubin ‘‘Rube’’<br />

Lacey, William James ‘‘Bill’’<br />

Lambert, Lloyd<br />

Lance, Major<br />

Landreth, Sonny<br />

Lane, Mary<br />

Lang, Eddie<br />

Lang, Jonny<br />

Lanor Records<br />

Larkin, Milton ‘‘Tippy’’<br />

LaSalle, Denise<br />

Lastie, David<br />

Latimore, Benny<br />

Laury, Booker T.<br />

Lawhorn, Samuel ‘‘Sammy’’<br />

Lawlars, Ernest ‘‘Little Son Joe’’<br />

Laws, Johnny<br />

Lay, Sam<br />

Lazy Lester<br />

Leadbelly<br />

Leadbitter, Michael Andrew ‘‘Mike’’<br />

Leake, Lafayette<br />

Leaner, George and Ernest<br />

Leary, S. P.<br />

Leavy, Calvin<br />

Leavy, Hosea<br />

Led Zeppelin<br />

Lee, Bonnie<br />

Lee, Frankie<br />

Lee, John Arthur<br />

Lee, Julia<br />

Lee, Lovie<br />

Leecan, Bobby<br />

Left Hand Frank<br />

Legendary <strong>Blues</strong> <strong>Band</strong><br />

Leiber and Stoller<br />

Leigh, Keri<br />

Lejeune, Iry<br />

Lembo, Kim<br />

Lenoir, J.B.<br />

Leonard, Harlan<br />

Let the Good Times Roll<br />

Levee <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Levy, Louis ‘‘Lou’’<br />

Levy, Morris<br />

Levy, Ron<br />

xx<br />

Lewis, Bobby<br />

Lewis, Furry<br />

Lewis, Johnie (Johnny)<br />

Lewis, Meade ‘‘Lux’’<br />

Lewis, Noah<br />

Lewis, Pete ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Lewis, Smiley<br />

Libraries<br />

Liggins, Jimmy<br />

Liggins, Joe<br />

Liggions, Dave<br />

Lightfoot, Alexander ‘‘Papa George’’<br />

Lightnin’ Slim<br />

Lincoln, Charlie<br />

Linkchain, Hip<br />

Lipscomb, Mance<br />

Liston, Virginia<br />

Literature, <strong>Blues</strong> in<br />

Little, Bobby<br />

Little Buster<br />

Little Charlie<br />

Little Mike<br />

Little Milton<br />

Little Miss Cornshucks<br />

Little Richard<br />

Little Sonny<br />

Little Walter<br />

Littlefield, ‘‘Little’’ Willie<br />

Littlejohn, John<br />

Lockwood, Robert, Jr.<br />

Lofton, ‘‘Cripple’’ Clarence<br />

Logan, John ‘‘Juke’’<br />

Lomax, Alan<br />

Lomax, John Avery<br />

London-American<br />

Lonesome Sundown<br />

Long, James Baxter ‘‘J. B.’’<br />

Lornell, Christopher ‘‘Kip’’<br />

Louis, Joe Hill<br />

Louisiana<br />

Louisiana Red<br />

Love, Clayton<br />

Love, Coy ‘‘Hot Shot’’<br />

Love, Preston<br />

Love, Willie<br />

Lowe, Sammy<br />

Lowery, Robert ‘‘Bob’’<br />

Lowry, Peter B. ‘‘Pete’’<br />

Lucas, William ‘‘Lazy Bill’’<br />

Lumber Camps<br />

LuPine<br />

Lusk, ‘‘Professor’’ Eddie<br />

Lutcher, Joe<br />

Lutcher, Nellie<br />

Lynching and the <strong>Blues</strong>

Lynn, Barbara<br />

Lynn, Trudy<br />

Lyons, Lonnie<br />

M<br />

M & O <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Mabon, Willie<br />

Mack, Lonnie<br />

MacLeod, Doug<br />

Macon, Albert<br />

Macon, John Wesley ‘‘Mr. Shortstuff’’<br />

Macon, Q. T.<br />

Macy’s<br />

Mad/M&M<br />

Maghett, Samuel Gene ‘‘Magic Sam’’<br />

Magic Slim<br />

Maiden, Sidney<br />

Maison du Soul<br />

Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor<br />

Malaco/Waldoxy<br />

Mallard, Sax<br />

Malo, Ron<br />

Malone, ‘‘John Jacob’’ J. J.<br />

Mama Talk to Your Daughter<br />

Mamlish Records<br />

Mandolin<br />

Mapleshade Records<br />

Mardi Gras<br />

Margolin, Bob<br />

Marketing<br />

Mars, Johnny<br />

Martin, Carl<br />

Martin, ‘‘Fiddlin’ ’’ Joe<br />

Martin, Sallie<br />

Martin, Sara<br />

Matchbox<br />

Matchbox <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Maxwell, David<br />

May, Roosevelt<br />

Mayall, John<br />

Mayes, Pete<br />

Mayfield, Curtis<br />

Mayfield, Percy<br />

Mays, Curley<br />

Mayweather, ‘‘Earring’’ George<br />

McCain, Jerry ‘‘Boogie’’<br />

McCall, Cash<br />

McClain, Mary ‘‘Diamond Teeth’’<br />

McClain, ‘‘Mighty’’ Sam<br />

McClennan, Tommy<br />

McClinton, Delbert<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

McClure, Bobby<br />

McCoy, Charlie<br />

McCoy, George and Ethel<br />

McCoy, ‘‘Kansas’’ Joe<br />

McCoy, Robert Edward<br />

McCoy, Rose Marie<br />

McCoy, Viola<br />

McCracklin, Jimmy<br />

McCray, Larry<br />

McDaniel, Clara ‘‘Big’’<br />

McDaniel, Floyd<br />

McDaniel, Hattie<br />

McDowell, Fred<br />

McGee, Cleo ‘‘Big Bo’’<br />

McGee, Reverend F. W.<br />

McGhee, Brownie<br />

McGhee, Granville ‘‘Sticks’’<br />

McGill, Rollee<br />

McGuirt, Clarence ‘‘Candyman’’<br />

McIlwaine, Ellen<br />

McKune, James<br />

McMahon, Andrew ‘‘Blueblood’’<br />

McMullen, Fred<br />

McNeely, Cecil James ‘‘Big Jay’’<br />

McPhatter, Clyde Lensley<br />

McPhee, Tony ‘‘T. S.’’<br />

McShann, James Columbus ‘‘Jay’’<br />

McTell, Blind Willie<br />

McVea, John Vivian ‘‘Jack’’<br />

Mean Mistreater Mama<br />

Meaux, Huey P.<br />

Medwick, Joe<br />

Melodeon Records<br />

Melotone<br />

Melrose, Lester<br />

Memphis<br />

Memphis <strong>Blues</strong>, The (‘‘Mama Don’ ’low’’<br />

or ‘‘Mister Crump’’)<br />

Memphis Jug <strong>Band</strong><br />

Memphis Minnie<br />

Memphis Piano Red<br />

Memphis Slim<br />

Mercury/Fontana/Keynote/Blue Rock<br />

Merritt<br />

MGM (55000 R&B series)<br />

Mickle, Elmon ‘‘Drifting Slim’’<br />

Mighty Clouds of Joy<br />

Milburn, Amos<br />

Miles, Josephine ‘‘Josie’’<br />

Miles, Lizzie<br />

Miles, Luke ‘‘Long Gone’’<br />

Miller, Clarence Horatio ‘‘Big’’<br />

Miller, Jay D. ‘‘J. D.’’<br />

Miller, Polk<br />

xxi

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Millet, McKinley ‘‘Li’l’’<br />

Millinder, Lucky<br />

Milton, Roy<br />

Miltone<br />

Minner, D. C.<br />

Miracle/Premium<br />

Miss Rhapsody<br />

Mississippi<br />

Mississippi Jook <strong>Band</strong><br />

Mississippi Matilda<br />

Mississippi Sheiks<br />

Mitchell, Bobby<br />

Mitchell, George<br />

Mitchell, ‘‘Little’’ Walter<br />

Mitchell, McKinley<br />

Mitchell, Willie<br />

Modern <strong>Blues</strong> Recordings<br />

Modern/Flair/Meteor/Kent/RPM<br />

Molton, Flora<br />

Montgomery, Eurreal ‘‘Little Brother’’<br />

Montgomery Ward<br />

Montoya, Coco<br />

Montrell, Roy<br />

Mooney, John<br />

Moore, Aaron<br />

Moore, Alexander ‘‘Whistlin’ Alex’’<br />

Moore, Alice ‘‘Little’’<br />

Moore, Dorothy<br />

Moore, Gary<br />

Moore, Johnny<br />

Moore, Johnny B.<br />

Moore, Monette<br />

Moore, Oscar<br />

Moore, Reverend Arnold Dwight ‘‘Gatemouth’’<br />

Moore, Samuel David ‘‘Sam’’<br />

Moore, William ‘‘Bill’’<br />

Morello, Jimmy<br />

Morgan, Mike<br />

Morgan, Teddy<br />

Morganfield, ‘‘Big’’ Bill<br />

Morisette, Johnny ‘‘Two-Voice’’<br />

Morton, Jelly Roll<br />

Mosaic<br />

Moss, Eugene ‘‘Buddy’’<br />

Moten, Benjamin ‘‘Bennie’’<br />

Motley, Frank Jr.<br />

Motown<br />

Mr. R&B Records<br />

Murphy, Matt ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Murphy, Willie<br />

Murray, Bobby<br />

Musselwhite, Charlie<br />

Mustang Sally<br />

My Black Mama (Walking <strong>Blues</strong>)<br />

Myers, Bob<br />

xxii<br />

Myers, Dave ‘‘Thumper’’<br />

Myers, Louis<br />

Myers, Sam<br />

N<br />

Naftalin, Mark<br />

Napier, Simon<br />

Nappy Chin<br />

Nardella, Steve<br />

Nashville<br />

Neal, Kenny<br />

Neal, Raful<br />

Neely, ‘‘Little’’ Bobby<br />

Negro Art<br />

Nelson, Chicago Bob<br />

Nelson, Jimmy ‘‘T-99’’<br />

Nelson, Romeo<br />

Nelson, Tracy<br />

Nettles, Isaiah<br />

Neville Brothers<br />

Newbern, Willie ‘‘Hambone Willie’’<br />

Newborn, Calvin<br />

Newborn, Phineas, Jr.<br />

Newell, ‘‘Little’’ Eddie<br />

Nicholson, James David ‘‘J. D.’’<br />

Nighthawk Records<br />

Nighthawk, Robert<br />

Nighthawks<br />

Nix, Willie<br />

Nixon, Elmore<br />

Nixon, Hammie<br />

Nolan, Lloyd<br />

Nolen, Jimmy<br />

North Mississippi AllStars<br />

Norwood, Sam<br />

Nulisch, Darrell<br />

O<br />

Oakland<br />

Oden, ‘‘St. Louis’’ Jimmy<br />

Odetta<br />

Odom, Andrew ‘‘Big Voice’’ ‘‘Little B. B.’’<br />

Offitt, Lillian<br />

Oh Pretty Woman (Can’t Make You Make Love Me)<br />

OJL (Origin Jazz Library)<br />

OKeh<br />

Old Swing-Master/Master<br />

Old Town<br />

Oldie <strong>Blues</strong>

Oliver, Paul<br />

Omar and the Howlers<br />

One Time <strong>Blues</strong>/Kokomo <strong>Blues</strong> (Sweet Home<br />

Chicago)<br />

O’Neal, Winston James ‘‘Jim’’<br />

One-derful/M-Pac/Mar-V-lus/Toddlin Town<br />

Opera<br />

Ora Nelle<br />

Oriole<br />

Orioles<br />

Orleans<br />

Oscher, Paul<br />

Otis, Johnny<br />

Otis, Shuggie<br />

Overbea, Danny<br />

Overstreet, Nathaniel ‘‘Pops’’<br />

Owens, Calvin<br />

Owens, Jack<br />

Owens, Jay<br />

Owens, Marshall<br />

P<br />

Page, Oran Thaddeus ‘‘Hot Lips’’<br />

Palm, Horace M.<br />

Palmer, Earl<br />

Palmer, Robert<br />

Palmer, Sylvester<br />

Paramount<br />

Parker, Charlie<br />

Parker, Herman, Jr.<br />

‘‘Little Junior’’ ‘‘Junior’’<br />

Parker, Sonny<br />

Parkway<br />

Parr, Elven ‘‘L. V.’’<br />

Pathé<br />

Patt, Frank ‘‘Honeyboy’’<br />

Patterson, Bobby<br />

Pattman, Neal<br />

Patton, Charley<br />

Payne, John W. ‘‘Sonny’’<br />

Payne, Odie Jr.<br />

Payton, Asie<br />

Peebles, Ann<br />

Peeples, Robert<br />

Peg Leg Sam<br />

Pejoe, Morris<br />

Perfect<br />

Periodicals<br />

Perkins, Al<br />

Perkins, Joe Willie ‘‘Pinetop’’<br />

Perry, Bill (Mississippi)<br />

Perry, Bill (New York)<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Perry, Oscar Lee<br />

Peterson, James<br />

Peterson, Lucky<br />

Petway, Robert<br />

Phelps, Kelly Joe<br />

Phelps, Walter<br />

Phillips, Brewer<br />

Phillips, Earl<br />

Phillips, Gene<br />

Phillips, Little Esther<br />

Phillips, Washington<br />

Piano<br />

Piano C. Red<br />

Piano Red<br />

Piazza, Rod<br />

Piccolo, Greg<br />

Pichon, Walter G. ‘‘Fats’’<br />

Pickens, Buster<br />

Pickett, Dan<br />

Piedmont (label)<br />

Piedmont (region)<br />

Pierce, Billie<br />

Pierson, Eugene<br />

Pierson, Leroy<br />

Ping<br />

Pinson, Reverend Leon<br />

Pitchford, Lonnie<br />

Pittman, Sampson<br />

Pittsburgh<br />

Plunkett, Robert<br />

Pomus, Jerome ‘‘Doc’’<br />

Poonanny<br />

Popa Chubby<br />

Porter, David<br />

Porter, Jake<br />

Porter, King<br />

Portnoy, Jerry<br />

Powell, Eugene<br />

Powell, Vance ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Prater, Dave<br />

Presley, Elvis Aron<br />

Preston, Jimmy<br />

Prez Kenneth<br />

Price, ‘‘Big’’ Walter ‘‘The Thunderbird’’<br />

Price, Lloyd<br />

Price, Sammy<br />

Primer, John<br />

Primich, Gary<br />

Professor Longhair<br />

Pryor, James Edward ‘‘Snooky’’<br />

Prysock, Arthur<br />

Prysock, Wilbert ‘‘Red’’<br />

Pugh, Joe Bennie ‘‘Forrest City Joe’’<br />

Pullum, Joe<br />

Puritan<br />

xxiii

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

P-Vine Special<br />

Pye/Nixa<br />

Q<br />

QRS<br />

Qualls, Henry<br />

Quattlebaum, Doug<br />

R<br />

R and B (1)<br />

R and B (2)<br />

Rachell, Yank<br />

Racial Issues and the <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Radcliff, Bobby<br />

Radio<br />

Railroads<br />

Rainey, Gertrude ‘‘Ma’’<br />

Rainey, Willie Guy<br />

Raitt, Bonnie<br />

Rankin, R. S.<br />

Rap<br />

Rapone, Al<br />

Rascoe, Moses<br />

Rawls, Johnny<br />

Rawls, Louis Allen ‘‘Lou’’<br />

Ray, Floyd<br />

Ray, Harmon<br />

Ray, Kenny ‘‘Blue’’<br />

RCA/Victor/Bluebird/Camden/Groove/X/Vik<br />

Recorded in Hollywood/Hollywood/<br />

Cash/Lucky/Money<br />

Recording<br />

Rector, Milton<br />

Red Lightnin’<br />

Red Rooster, The<br />

Reed, A. C.<br />

Reed, Dalton<br />

Reed, Francine<br />

Reed, Jimmy<br />

Reed, Lula<br />

Reed, Mama<br />

Reynolds, Big Jack<br />

Reynolds, Blind Joe<br />

Reynolds, Theodore ‘‘Teddy’’<br />

Rhino<br />

Rhodes, Sonny<br />

Rhodes, Todd<br />

Rhodes, Walter ‘‘Lightnin’ Bug’’<br />

xxiv<br />

Rhumboogie<br />

Rhythm<br />

Rhythm and <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Rhythm Willie<br />

Ric<br />

Rice, ‘‘Sir Mack’’ Bonny<br />

Richard, Rudolph ‘‘Rudy’’<br />

Richardson, C. C.<br />

Richardson, Mona<br />

Richbourg, John<br />

Ricks, ‘‘Philadelphia’’ Jerry<br />

Ridgley, Thomas ‘‘Tommy’’<br />

Riedy, Bob<br />

Riggins, Richard ‘‘Harmonica Slim’’<br />

Riley, Judge Lawrence<br />

Rishell, Paul<br />

Rivers, Boyd<br />

Roberts, Roy<br />

Robicheaux, Coco<br />

Robillard, Duke<br />

Robinson, Alvin ‘‘Shine’’<br />

Robinson, Arthur Clay ‘‘A. C.’’<br />

Robinson, Bobby<br />

Robinson, Elzadie<br />

Robinson, Fenton<br />

Robinson, Freddy<br />

Robinson, James ‘‘Bat The Hummingbird’’<br />

Robinson, Jessie Mae<br />

Robinson, Jimmie Lee<br />

Robinson, L. C. ‘‘Good Rockin’’’<br />

Robinson, Tad<br />

Rochester, NY<br />

Rock ’n’ Roll<br />

Rockin’ Dopsie<br />

Rockin’/Glory<br />

Rodgers, James Charles ‘‘Jimmie’’<br />

Rodgers, Sonny ‘‘Cat Daddy’’<br />

Rogers, Jimmy<br />

Rogers, Roy<br />

Roland, Walter<br />

Roll and Tumble <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Rolling Stones<br />

Romeo<br />

Ron<br />

Roomful of <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Rooster <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Roots/Paltram/Truth/For Specialists Only<br />

Rosetta Records<br />

Ross, Doctor Isaiah<br />

Rothchild, Paul A.<br />

Roulette, Freddie<br />

Roulette/Rama<br />

Rounder<br />

Rounds, Ernestine Smith<br />

Roy, Earnest ‘‘Guitar’’

Royal, Marshal<br />

RST/RST <strong>Blues</strong> Document/Fantasy By<br />

Rubboard<br />

Rush, Bobby<br />

Rush, Otis<br />

Rushing, James Andrew ‘‘Jimmy’’<br />

Russell, Tommie Lee<br />

Rykodisc<br />

S<br />

Sadler, Haskell Robert ‘‘Cool Papa’’<br />

Saffire–The Uppity <strong>Blues</strong> Women<br />

Sain, Oliver<br />

Salgado, Curtis<br />

Samples, John T.<br />

San Francisco<br />

Sanders, Will Roy ‘‘Wilroy’’<br />

Sane, Dan<br />

Sanford, Amos ‘‘Little’’<br />

SAR/Derby<br />

Satherly, Art<br />

Saunders, Red<br />

Savoy Brown<br />

Savoy/National/Regent/Acorn<br />

Saxophone<br />

Saydak, Ken<br />

Sayles, Charlie<br />

Sayles, Johnny<br />

Scales<br />

Scales, Alonzo ‘‘Lonnie’’<br />

Scepter/Wand<br />

Scott, Buddy<br />

Scott, Clifford<br />

Scott, Ecrettia Jacobs ‘‘E. C.’’<br />

Scott, Esther Mae ‘‘Mother’’<br />

Scott, James, Jr.<br />

Scott, Joe<br />

Scott, ‘‘Little’’ Jimmy<br />

Scott, Marylin<br />

Scott, Sonny<br />

Scott-Adams, Peggy<br />

Scruggs, Irene<br />

SD (Steiner Davis)<br />

Seals, Son<br />

Sears, ‘‘Big’’ Al<br />

Sease, Marvin<br />

See That My Grave Is Kept Clean<br />

Seeley, Bob<br />

Sellers, Brother John<br />

Semien, ‘‘King Ivory’’ Lee<br />

Senegal, Paul ‘‘Lil’ Buck’’<br />

Sensation<br />

Sequel<br />

7-11<br />

Seward, Alexander T. ‘‘Alec’’<br />

Sex as Lyric Concept<br />

Seymour<br />

Shad<br />

Shake ’Em on Down<br />

Shakey Jake<br />

Shama<br />

Shanachie/Yazoo/Belzona/Blue Goose<br />

Shannon, Mem<br />

Shannon, Preston<br />

Shaw, Allen<br />

Shaw, Eddie<br />

Shaw, Eddie ‘‘Vaan,’’ Jr.<br />

Shaw, Robert<br />

Shaw, Thomas ‘‘Tom’’<br />

Shepherd, Kenny Wayne<br />

Sheppard, Bill ‘‘Bunky’’<br />

Shields, Lonnie<br />

Shines, Johnny<br />

Shirley & Lee<br />

Short, J. D.<br />

Shower, ‘‘Little’’ Hudson<br />

Siegel-Schwall <strong>Band</strong><br />

Signature<br />

Signifying Monkey, The<br />

Simien, ‘‘Rockin’ ’’ Sidney<br />

Simmons, Malcolm ‘‘Little Mack’’<br />

Sims, Frankie Lee<br />

Sims, Henry ‘‘Son’’<br />

Since I Met You Baby<br />

Singer, Hal<br />

Singing<br />

Singleton, T-Bone<br />

Sirens<br />

Sista Monica<br />

Sittin’ In With/Jade/Jax/Mainstream<br />

Sloan, Henry<br />

Small, Drink<br />

Smith, Albert ‘‘Al’’<br />

Smith, ‘‘Barkin’ ’’ Bill<br />

Smith, Bessie<br />

Smith, Boston<br />

Smith, Buster<br />

Smith, Byther<br />

Smith, Carrie<br />

Smith, Clara<br />

Smith, Clarence ‘‘Pine Top’’<br />

Smith, Effie<br />

Smith, Floyd<br />

Smith, George ‘‘Harmonica’’<br />

Smith, Huey ‘‘Piano’’<br />

Smith, J. B.<br />

Smith, John T.<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xxv

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Smith, Lucius<br />

Smith, Mamie<br />

Smith, Moses ‘‘Whispering’’<br />

Smith, Robert Curtis<br />

Smith, Talmadge ‘‘Tab’’<br />

Smith, Trixie<br />

Smith, Willie ‘‘Big Eyes’’<br />

Smith, Willie Mae Ford ‘‘Mother’’<br />

Smither, Chris<br />

Smokestack Lightning<br />

Smokey Babe<br />

Smothers, Abraham ‘‘Little Smokey’’<br />

Smothers, Otis ‘‘Big Smokey’’<br />

Snow, Eddie<br />

Soileau, Floyd<br />

Solberg, James<br />

Solomon, Clifford<br />

Sons of <strong>Blues</strong>, The (The S.O.B. <strong>Band</strong>)<br />

SONY/Legacy/Columbia/Epic/OKeh<br />

Soul<br />

Sound Stage 7<br />

Spady, Clarence<br />

Spain<br />

Spand, Charlie<br />

Spann, Lucille<br />

Spann, Otis<br />

Spann, Pervis<br />

Sparks Brothers<br />

Specialty/Fidelity/Juke Box<br />

Speckled Red<br />

Specter, Dave<br />

Speir, H.C.<br />

Spencer, Evans<br />

Spire<br />

Spires, Arthur ‘‘Big Boy’’<br />

Spires, Bud<br />

Spirit of Memphis Quartet<br />

Spivey, Addie ‘‘Sweet Pease’’<br />

Spivey, Elton ‘‘The Za Zu Girl’’<br />

Spivey Records<br />

Spivey, Victoria<br />

Spoonful (A Spoonful <strong>Blues</strong>)<br />

Spoons<br />

Sprott, Horace<br />

Spruell, Freddie<br />

Spruill, James ‘‘Wild Jimmy’’<br />

St. Louis <strong>Blues</strong><br />

St. Louis, Missouri<br />

Stack Lee<br />

Stackhouse, Houston<br />

Staff/Dessa<br />

Staples, Roebuck ‘‘Pops’’<br />

Star Talent/Talent<br />

Stark, Cootie<br />

Starr Piano Company<br />

xxvi<br />

Stash Records<br />

Stax/Volt<br />

Steiner, John<br />

Stephens, James ‘‘Guitar Slim’’<br />

Stepney, Billie<br />

Stidham, Arbee<br />

Stinson Records<br />

Stokes, Frank<br />

Stone, Jesse<br />

Stormy Monday<br />

Storyville Records<br />

Stovall, Jewell ‘‘Babe’’<br />

Stovepipe No. 1<br />

Straight Alky <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Strehli, Angela<br />

Stroger, Bob<br />

Strother, James ‘‘Jimmie’’<br />

Strother, Percy<br />

Stuckey, Henry<br />

Studebaker John<br />

Sue (1)<br />

Sue (2)<br />

Sugar Blue<br />

Sultan<br />

Sumlin, Hubert<br />

Sun/Phillips International/Flip<br />

Sunbeam<br />

Sunnyland Slim<br />

Sunrise (postwar)<br />

Sunrise (prewar)<br />

Super Chikan<br />

Super Disc<br />

Superior<br />

Supertone<br />

Supreme<br />

Swan Silvertone Singers<br />

Sweden<br />

Sweet Honey in the Rock<br />

Sweet Miss Coffy<br />

Swing Time/Down Beat<br />

Sykes, Roosevelt<br />

Sylvester, Hannah<br />

T<br />

Taggart, Blind Joe<br />

Tail Dragger<br />

Taj Mahal<br />

Takoma<br />

Talbot, Johnny<br />

Talty, Don<br />

Tampa Red

Tangerine Records<br />

Tarheel Slim<br />

Tarnopol, Nat<br />

Tarrant, Rabon<br />

Tarter and Gay<br />

Tasby, Finis<br />

Tate, Buddy<br />

Tate, Charles Henry ‘‘Baby’’<br />

Tate, Tommy<br />

Taylor, Eddie<br />

Taylor, Eva<br />

Taylor, Hound Dog<br />

Taylor, Johnnie Harrison<br />

Taylor, Johnny Lamar ‘‘Little’’<br />

Taylor, Koko<br />

Taylor, Melvin<br />

Taylor, Montana<br />

Taylor, Otis<br />

Taylor, Sam ‘‘Bluzman’’<br />

Taylor, Sam ‘‘The Man’’<br />

Taylor, Ted<br />

Tedeschi, Susan<br />

Telarc<br />

Television<br />

Temple, Johnny ‘‘Geechie’’<br />

Tempo-Tone<br />

Ten Years After<br />

Tennessee<br />

Terry, Cooper<br />

Terry, Doc<br />

Terry, Sonny<br />

Testament<br />

Texas<br />

Thackery, Jimmy<br />

Tharpe, Sister Rosetta<br />

Theard, Sam ‘‘Spo-Dee-O-Dee’’<br />

Theater, <strong>Blues</strong> in<br />

Theron<br />

Thierry, Huey Peter ‘‘Cookie’’<br />

This Train (My Babe)<br />

Thomas, Blanche<br />

Thomas, Earl<br />

Thomas, Elmer Lee<br />

Thomas, Frank, Jr.<br />

Thomas, George<br />

Thomas, Henry ‘‘Ragtime Texas’’<br />

Thomas, Hersal<br />

Thomas, Hociel<br />

Thomas, Irma<br />

Thomas, James ‘‘Son’’ ‘‘Ford’’<br />

Thomas, Jesse ‘‘Babyface’’<br />

Thomas, Joe<br />

Thomas, Lafayette Jerl ‘‘Thing’’<br />

Thomas, Leon<br />

Thomas, Robert<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

Thomas, Rufus<br />

Thomas, Tabby<br />

Thomas, Willard ‘‘Rambling’’<br />

Thomas, Willie B.<br />

Thompson, Alphonso ‘‘Sonny’’<br />

Thompson, David ‘‘Little Dave’’<br />

Thompson, Mac<br />

Thompson, Odell<br />

Thompson, Ron<br />

Thornton, Willie Mae<br />

‘‘Big Mama’’<br />

Thorogood, George<br />

Tibbs, Andrew<br />

Tight Like That<br />

Timmons, Terry<br />

Tinsley, John E.<br />

Tip Top<br />

Tisdom, James ‘‘Smokestack’’<br />

TOBA<br />

Tomato Records<br />

Tone-Cool<br />

Too Tight Henry<br />

Top Cat<br />

Topical <strong>Blues</strong>: Disasters<br />

Topical <strong>Blues</strong>: Sports<br />

Topical <strong>Blues</strong>: Urban Renewal<br />

Toure, Ali Farka<br />

Toussaint, Allen<br />

Townsend, Henry<br />

Townsend, Vernell Perry<br />

Transatlantic<br />

Transcription<br />

Treniers<br />

Tribble, Thomas E. ‘‘TNT’’<br />

Trice, Richard<br />

Trice, William Augusta ‘‘Willie’’<br />

Trilon<br />

Tri-sax-ual Soul Champs<br />

Trix<br />

Trout, Walter<br />

Trucks, Derek<br />

Trumpet Records/Globe Music/Diamond<br />

Record Company<br />

Tucker, Bessie<br />

Tucker, Ira<br />

Tucker, Luther<br />

Tucker, Tommy<br />

Turner, Ike<br />

Turner, Joseph Vernon ‘‘Big Joe’’<br />

Turner, Othar<br />

Turner, Troy<br />

Turner, Twist<br />

TV Slim<br />

Twinight/Twilight<br />

Tyler, Alvin ‘‘Red’’<br />

xxvii

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

U<br />

United Kingdom and Ireland<br />

United States<br />

United/States<br />

Upchurch, Phil<br />

USA<br />

V<br />

Valentine, Cal<br />

Van Ronk, Dave<br />

Van Singel, Amy<br />

Vanguard<br />

Vanleer, Jimmy<br />

Varsity<br />

Vaughan, Jimmy<br />

Vaughan, Stevie Ray<br />

Vaughn, Jimmy<br />

Vaughn, Maurice John<br />

Vault<br />

Vee-Jay/Abner/Falcon<br />

Venson, Tenner ‘‘Playboy’’ ‘‘Coot’’<br />

Verve<br />

Vicksburg <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Victor<br />

Vinson, Eddie ‘‘Cleanhead’’<br />

Vinson, Mose<br />

Vinson, Walter<br />

Violence as Lyric Concept<br />

Vita<br />

Vitacoustic<br />

Vocalion<br />

Vogue<br />

W<br />

Walker, Blind Willie<br />

Walker, Charles<br />

Walker, Dennis<br />

Walker, George ‘‘Chicken George’’<br />

Walker, Jimmy<br />

Walker, Joe Louis<br />

Walker, Johnny Mayon ‘‘Big Moose’’<br />

Walker, Junior<br />

Walker, Phillip<br />

Walker, Robert ‘‘Bilbo’’<br />

Walker, T-Bone<br />

Wallace, Sippie<br />

Wallace, Wesley<br />

xxviii<br />

Walls, Harry Eugene Vann ‘‘Piano Man’’<br />

Walton, Mercy Dee<br />

Walton, Wade<br />

Ward, Robert<br />

Wardlow, Gayle Dean<br />

Warren, Robert Henry ‘‘Baby Boy’’<br />

Washboard Doc<br />

Washboard Sam<br />

Washboard Slim<br />

Washboard Willie<br />

Washington (state)<br />

Washington, Albert<br />

Washington, Dinah<br />

Washington, Isidore ‘‘Tuts’’<br />

Washington, Leroy<br />

Washington, Marion ‘‘Little Joe’’<br />

Washington, Toni Lynn<br />

Washington, Walter ‘‘Wolfman’’<br />

Waterford, Charles ‘‘Crown Prince’’<br />

Waterman, Richard A. ‘‘Dick’’<br />

Waterman, Richard Alan<br />

Waters, Ethel<br />

Waters, Mississippi Johnny<br />

Waters, Muddy<br />

Watkins, Beverly ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Watkins, John ‘‘Mad Dog’’<br />

Watson, Johnny ‘‘Daddy Stovepipe’’<br />

Watson, Johnny ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Watson, Mike ‘‘Junior’’<br />

Watts, Louis Thomas<br />

Watts, Noble ‘‘Thin Man’’<br />

Weathersby, Carl<br />

Weaver, James ‘‘Curley’’<br />

Weaver, Sylvester<br />

Webb, ‘‘Boogie’’ Bill<br />

Webb, Willie ‘‘Jitterbug’’<br />

Webster, Katie<br />

Weepin’ Willie<br />

Welch, ‘‘Monster’’ Mike<br />

Welding, Pete<br />

Weldon, Casey Bill<br />

Wellington, Valerie<br />

Wells, Junior<br />

Wells, Michael ‘‘Lightnin’ ’’<br />

West, Charlie<br />

Weston, John<br />

Westside<br />

Wheatstraw, Peetie<br />

Wheeler, Golden ‘‘Big’’<br />

Wheeler, Thomas James ‘‘T.J.’’<br />

Whistler’s Jug <strong>Band</strong><br />

Whitaker, ‘‘King’’ Herbert<br />

White, Artie ‘‘<strong>Blues</strong> Boy’’<br />

White, Bukka<br />

White, Cleve ‘‘Schoolboy Cleve’’

White, Georgia<br />

White, Joshua Daniel ‘‘Josh’’<br />

White, Lynn<br />

White, Miss Lavelle<br />

Wiggins, Phil<br />

Wilborn, Nelson<br />

(‘‘Red Nelson,’’ ‘‘Dirty Red’’)<br />

Wiley, Geechie<br />

Wilkins, Joe Willie<br />

Wilkins, Lane<br />

Wilkins, Reverend Robert Timothy ‘‘Tim’’<br />

Williams, Andre ‘‘Mr. Rhythm’’<br />

Williams, Andy ‘‘Too-Hard’’<br />

Williams, Arbess<br />

Williams, Arthur Lee ‘‘Oscar Mississippi’’<br />

Williams, ‘‘Big’’ Joe Lee<br />

Williams, Bill<br />

Williams, Charles Melvin ‘‘Cootie’’<br />

Williams, Clarence<br />

Williams, Ed ‘‘Lil’ Ed’’<br />

Williams, George ‘‘Bullet’’<br />

Williams, Henry ‘‘Rubberlegs’’<br />

Williams, J. Mayo<br />

Williams, Jabo<br />

Williams, Jimmy Lee<br />

Williams, Joe<br />

Williams, Johnny (1)<br />

Williams, Johnny (2)<br />

Williams, Joseph ‘‘Jo Jo’’<br />

Williams, Joseph Leon ‘‘Jody’’<br />

Williams, L. C.<br />

Williams, Larry<br />

Williams, Lee ‘‘Shot’’<br />

Williams, Lester<br />

Williams, Nathan<br />

Williams, Paul ‘‘Hucklebuck’’<br />

Williams, Robert Pete<br />

Williams, Willie ‘‘Rough Dried’’<br />

Williamson, Sonny Boy I (John Lee Williamson)<br />

Williamson, Sonny Boy II (Aleck Miller)<br />

Willis, Harold ‘‘Chuck’’<br />

Willis, Ralph<br />

Willis, Robert Lee ‘‘Chick’’<br />

Willis, Willie<br />

Willson, Michelle<br />

Wilmer, Val<br />

Wilson, Al<br />

Wilson, Charles<br />

Wilson, Edith<br />

Wilson, Harding ‘‘Hop’’<br />

Wilson, Jimmy<br />

Wilson, Kim<br />

Wilson, Lena<br />

Wilson, Quinn<br />

Wilson, Smokey<br />

Wilson, U. P.<br />

Winter, Johnny<br />

Withers, Earnest<br />

Witherspoon, Jimmy<br />

Wolf/Best of <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Wolfman Jack<br />

Women and the <strong>Blues</strong><br />

Woodfork, ‘‘Poor’’ Bob<br />

Woods, Johnny<br />

Woods, Mitch<br />

Woods, Oscar ‘‘Buddy’’<br />

Work with Me Annie<br />

World War II<br />

Wrencher, ‘‘Big’’ John Thomas<br />

Wright, Billy<br />

Wright, Early<br />

Wright, Marva<br />

Wright, Overton Ellis ‘‘O. V.’’<br />

Y<br />

Yancey, James Edward(s) ‘‘Jimmy’’<br />

Yancey, Mama Estelle<br />

Yardbirds<br />

Young, Johnny<br />

Young, ‘‘Mighty’’ Joe<br />

Young, Zora<br />

Z<br />

Ziegler, John Lee<br />

Zinn, Rusty<br />

ZZ Top<br />

LIST OF ENTRIES A–Z<br />

xxix

Biographical Entries<br />

THEMATIC LIST OF ENTRIES<br />

Abner, Ewart<br />

Abshire, Nathan<br />

Ace, Buddy<br />

Ace, Johnny<br />

Aces, The<br />

Acey, Johnny<br />

Acklin, Barbara<br />

Adams, Alberta<br />

Adams, Arthur<br />

Adams, Dr. Jo Jo<br />

Adams, Faye<br />

Adams, John Tyler ‘‘J. T.’’<br />

Adams, Johnny<br />

Adams, Marie<br />

Adams, Woodrow Wilson<br />

Adins, Joris ‘‘Georges’’<br />

Admirals, The<br />

Agee, Raymond Clinton ‘‘Ray’’<br />

Agwada, Vince<br />

Akers, Garfield<br />

Alexander, Algernon ‘‘Texas’’<br />

Alexander, Arthur<br />

Alexander, Dave (Omar Hakim Khayyam)<br />

Alix, May<br />

Allen, Annisteen<br />

Allen, Bill ‘‘Hoss’’<br />

Allen, Lee<br />

Allen, Pete<br />

Allen, Ricky<br />

Allison, Bernard<br />

Allison, Luther<br />

Allison, Mose<br />

Allison, Ray ‘‘Killer’’<br />

Allman Brothers <strong>Band</strong><br />

Alston, Jamie<br />

Altheimer, Joshua ‘‘Josh’’<br />

Amerson, Richard<br />

Ammons, Albert<br />

Anderson, Alvin ‘‘Little Pink’’<br />

Anderson, Bob ‘‘Little Bobby’’<br />

Anderson, Elester<br />

Anderson, Jimmy<br />

Anderson, Kip<br />

xxxi<br />

Anderson, ‘‘Little’’ Willie<br />

Anderson, Pinkney ‘‘Pink’’<br />

Animals<br />

Arcenaux, Fernest<br />

Archia, Tom<br />

Archibald<br />

Ardoin, Alphonse ‘‘Bois Sec’’<br />

Ardoin, Amédé<br />

Armstrong, Howard ‘‘Louie Bluie’’<br />

Armstrong, James<br />

Armstrong, Louis<br />

Armstrong, Thomas Lee ‘‘Tom’’<br />

Arnett, Al<br />

Arnold, Billy Boy<br />

Arnold, Jerome<br />

Arnold, Kokomo<br />

Arrington, Manuel<br />

Ashford, R. T.<br />

August, Joe ‘‘Mr. Google Eyes’’<br />

August, Lynn<br />

Austin, Claire<br />

Austin, Jesse ‘‘Wild Bill’’<br />

Austin, Lovie<br />

Bailey, Deford<br />

Bailey, Kid<br />

Bailey, Mildred<br />

Bailey, Ray<br />

Baker, Etta<br />

Baker, Houston<br />

Baker, LaVern<br />

Baker, Mickey<br />

Baker, Willie<br />

Baldry, ‘‘Long’’ John<br />

Ball, Marcia<br />

Ballard, Hank<br />

Ballou, Classie<br />

Bankhead, Tommy<br />

Banks, Chico<br />

Banks, Jerry<br />

Banks, L. V.<br />

Bankston, Dick<br />

Baraka, Amiri<br />

Barbecue Bob<br />

Barbee, John Henry<br />

Barker, Blue Lu

THEMATIC LIST OF ENTRIES<br />

Barker, Danny<br />

Barksdale, Everett<br />

Barner, Wiley<br />

Barnes, George<br />

Barnes, Roosevelt Melvin ‘‘Booba’’<br />

Bartholomew, Dave<br />

Barton, Lou Ann<br />

Bascomb, Paul<br />

Basie, Count<br />

Bass, Fontella<br />

Bass, Ralph<br />

Bassett, Johnnie<br />

Bastin, Bruce<br />

Bates, Lefty<br />

Batts, Will<br />

Beaman, Lottie<br />

Beard, Chris<br />

Beard, Joe<br />

Beasley, Jimmy<br />

Beauregard, Nathan<br />

Belfour, Robert<br />

Bell, Brenda<br />

Bell, Carey<br />

Bell, Earl<br />

Bell, Ed<br />

Bell, Jimmie<br />

Bell, Lurrie<br />

Bell, T. D.<br />

Below, Fred<br />

Below, LaMarr Chatmon<br />

Belvin, Jesse<br />

Bender, D. C.<br />

Bennet, Bobby ‘‘Guitar’’<br />

Bennett, Anthony ‘‘Duster’’<br />

Bennett, Wayne T.<br />

Benoit, Tab<br />

Benson, Al<br />

Bentley, Gladys Alberta<br />

Benton, Brook<br />

Benton, Buster<br />

Bernhardt, Clyde (Edric Barron)<br />

Berry, Chuck<br />

Berry, Richard<br />

Bibb, Eric<br />

Big Bad Smitty<br />

Big Doo Wopper<br />

Big Lucky<br />

Big Maceo<br />

Big Maybelle<br />

Big Memphis Ma Rainey<br />

Big Three Trio<br />

Big Time Sarah<br />

Big Twist<br />

Bigeou, Esther<br />

Billington, Johnnie<br />

xxxii<br />

Binder, Dennis ‘‘Long Man’’<br />

Bishop, Elvin<br />

Bizor, Billy<br />

Black Ace<br />

Black Bob<br />

Blackwell, Otis<br />

Blackwell, Robert ‘‘Bumps’’<br />

Blackwell, Scrapper<br />

Blackwell, Willie ‘‘61’’<br />

Blake, Cicero<br />

Bland, Bobby ‘‘Blue’’<br />

Blanks, Birleanna<br />

Blaylock, Travis ‘‘Harmonica Slim’’<br />

Blind Blake<br />

Block, Rory<br />

Bloomfield, Michael<br />

Blue, Little Joe<br />

Blue Smitty<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Boy Willie<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Brothers<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Incorporated<br />

<strong>Blues</strong> Project<br />

<strong>Blues</strong>breakers<br />

Bo, Eddie<br />

Bogan, Lucille<br />

Bogan, Ted<br />

Bogart, Deanna<br />

Bohee Brothers<br />

Boines, Sylvester<br />

Boll Weavil Bill<br />

Bollin, Zuzu<br />

Bond, Graham<br />

Bonds, Son<br />

Bonner, Weldon H. Phillip ‘‘Juke Boy’’<br />

Boogie Jake<br />

Boogie Woogie Red<br />

Book Binder, Roy<br />

Booker, Charlie (Charley)<br />

Booker, James<br />

Booze, Beatrice ‘‘Wee Bea’’<br />

Borum, ‘‘Memphis’’ Willie<br />

Bostic, Earl<br />

Boston Blackie<br />

Bouchillon, Chris<br />

Bowman, Priscilla<br />

Bowser, Erbie<br />

Boy Blue<br />

Boyack, Pat<br />

Boyd, Eddie<br />

Boyd, Louie<br />

Boykin, Brenda<br />

Boyson, Cornelius ‘‘Boysaw’’<br />

Boze, Calvin B.<br />

Bracey, Ishmon<br />

Bracken, James C.

Bradford, Perry<br />

Bradshaw, Evans<br />

Bradshaw, Myron ‘‘Tiny’’<br />

Braggs, Al ‘‘TNT’’<br />

Bramhall, Doyle<br />

Branch, William Earl ‘‘Billy’’<br />

Brandon, Skeeter<br />

Brenston, Jackie<br />

Brewer, Clarence ‘‘King Clarentz’’<br />

Brewer, Jim ‘‘Blind’’<br />

Brewster, Rev. William Herbert<br />

Bridges, Curley<br />

Brim, Grace<br />

Brim, John<br />

Brim, John Jr.<br />

Britton, Joe<br />

Brockman, Polk<br />

Brooks, ‘‘Big’’ Leon<br />

Brooks, Columbus<br />

Brooks, Hadda<br />

Brooks, Lonnie<br />

Broonzy, Big Bill<br />

Brown, Ada<br />

Brown, Andrew<br />

Brown, Arelean<br />

Brown, Bessie (Ohio)<br />

Brown, Bessie (Texas)<br />

Brown, Buster<br />

Brown, Charles<br />

Brown, Clarence ‘‘Gatemouth’’<br />

Brown, Cleo<br />

Brown, Dusty<br />

Brown, Gabriel<br />

Brown, Hash<br />

Brown, Henry ‘‘Papa’’<br />

Brown, Ida G.<br />

Brown, J. T.<br />

Brown, James<br />

Brown, John Henry ‘‘Bubba’’<br />

Brown, Lillyn<br />

Brown, Nappy<br />

Brown, Olive<br />

Brown, Oscar III ‘‘Bobo’’<br />

Brown, Pete<br />

Brown, Richard ‘‘Rabbit’’<br />

Brown, Roy James<br />

Brown, Ruth<br />

Brown, ‘‘Texas’’ Johnny<br />

Brown, Walter<br />

Brown, Willie Lee<br />

Brozman, Bob<br />

Bruynoghe, Yannick<br />

Bryant, Beulah<br />

Bryant, Precious<br />

Bryant, Rusty<br />

Buchanan, Roy<br />

Buckner, Willie (Willa) Mae<br />

Buckwheat Zydeco<br />

Buford, George ‘‘Mojo’’<br />

Bull City Red<br />

Bunn, Teddy<br />

Burks, Eddie<br />

Burley, Dan<br />

Burns, Eddie<br />

Burns, Jimmy<br />

Burnside, R. L.<br />

Burrage, Harold<br />

Burris, J.C.<br />

Burrow, Cassell<br />

Burse, Charlie<br />

Burton, Aron<br />

Butler, George ‘‘Wild Child’’<br />

Butler, Henry<br />

Butler, Jerry<br />

Butler Twins<br />

Butterbeans and Susie<br />

Butterfield, Paul<br />

Byrd, John<br />

Cadillac Baby<br />

Caesar, Harry ‘‘Little’’<br />

Cage, James ‘‘Butch’’<br />

Cain, Chris<br />

Cain, Perry<br />

Callender, Red<br />

Callicott, Joe<br />

Calloway, Cab<br />

Calloway, Harrison<br />

Campbell, ‘‘Blind’’ James<br />

Campbell, Carl<br />

Campbell, Eddie C.<br />

Campbell, John<br />

Canned Heat<br />

Cannon, Gus<br />

Carbo, Hayward ‘‘Chuck’’<br />

Carbo, Leonard ‘‘Chick’’<br />

Carmichael, James ‘‘Lucky’’<br />

Carolina Slim<br />

Caron, Danny<br />

Carr, Barbara<br />

Carr, Leroy<br />