AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 1

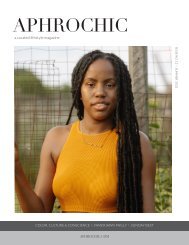

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together. On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together.

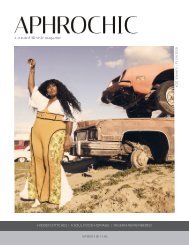

On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ARTISTS & ARTISANS<br />

The Cameroonian Juju Hat<br />

An explosion of plumage, pops of bright festive colors, Cameroonian juju hats have spent<br />

the last few years becoming synonymous with global style in home decor. Originally<br />

meant to decorate people, rather than rooms, their popularity has grown to the point<br />

that lately it seems that no room is complete without one of these beautiful feathered<br />

pieces on the walls. Yet, while juju hats are a common sight on the walls of many modern<br />

interiors, for the Bamileke people of Western Cameroon they were once a rare item<br />

reserved only for a select few.<br />

Like most Bamileke art, juju hats<br />

are created specifically for use at royal<br />

festivals or ceremonies. The frame is<br />

constructed from raffia that is woven to<br />

create the support structure. Feathers<br />

taken from a chicken, guinea hen, or<br />

other wild bird are dyed and attached<br />

to the base. A leather strap attached to<br />

the back is used to pull the hat open to<br />

its full breadth. When not in use, the<br />

hat folds up into a manageable bundle<br />

that not only helps with storage, but<br />

also acts to protect the feathers within<br />

the shell of the much tougher raffia<br />

structure. Protecting the delicate<br />

feathers is a high priority, as the hats<br />

play an important societal role.<br />

In Bamileke societies, the king,<br />

called a Fon, is attended by a committee<br />

of eight men known as the Mkem or<br />

“the assembly of holders of hereditary<br />

rights.” Each man of this council<br />

acts as the head of a particular society<br />

tasked with certain duties within the<br />

kingdom. Every two years the Mkem<br />

hold special meetings at which the<br />

wealth of the king is displayed and each<br />

member dons masks appropriate to<br />

their societies. The most venerated of<br />

these, the elephant and leopard masks,<br />

are reserved only for the king and for<br />

members of the Kuosi and the Kemdje,<br />

both warrior societies. It is with these<br />

masks that Tyn or juju hats are most<br />

commonly seen, though occasionally<br />

they are also worn alone, like on the<br />

death of a king or a wealthy member of<br />

one of the eight societies.<br />

One of the biggest questions about<br />

these hats is what to call them. Juju<br />

is not a term found in any Bamileke<br />

language and no one is sure where it<br />

came from. Two theories are that it is<br />

either a derivation of the word “djudju,”<br />

used by the Hausa of northern Nigeria<br />

to denote an evil spirit, or from the<br />

French “joujou,” meaning a trifle or toy.<br />

From the time of its first recorded<br />

use in the late 17th century, juju became<br />

a popular term among Europeans for<br />

referring to West African religions and<br />

their healers who were called juju men.<br />

It may be that an observer mistook the<br />

wearers of these hats for such healers<br />

and applied the name by which we<br />

now know the feathered hats that the<br />

Bamileke call Tyn.<br />

<br />

aphrochic