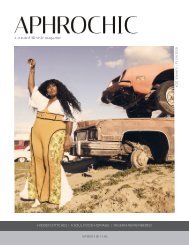

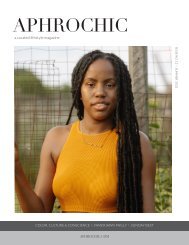

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 1

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together. On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Welcome to the Fall 2019 issue of AphroChic Magazine. Designed to celebrate the presence, innovation and accomplishments of creatives of color from all corners of the African Diaspora, we welcome the season in this issue with a focus on fashion, authentic beauty, and creating moments that bind us together.

On the cover, New York fashion stylists, Courtney and Donnell Baldwin of Mr. Baldwin Style invite us to experience a fête in a historic part of Sag Harbor. We take a look inside the Brooklyn home of fashion designer and movement artist, Nana Yaa Asare-Boadu and experience her effortless aesthetic. Then, we go half way around the world on a photographic journey of Morocco, with photographer Lauren Crew. Along the way, you’ll find articles that explore the nature of the African Diaspora, the importance of the Black family home, and the books, art and accessories you’ll want to bring home this season.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Reference<br />

two millennia, diaspora was used<br />

almost exclusively to refer to dispersed<br />

Jewish populations throughout history.<br />

But by the 20th century other groups<br />

had begun using the word as a designator.<br />

Armenian writers begin focusing<br />

on displacement in their work as early<br />

as 1915, while the African Diaspora<br />

sees its first mention by the late 1960s.<br />

It wasn’t until the early ‘90s that the<br />

explosion of communities regarded<br />

as diaspora began an expansion of the<br />

term. The trend has continued into the<br />

21st century, expanding the application<br />

of the term beyond national dispersions<br />

to include the many groups that inhabit<br />

the concept today.<br />

In 2000, listing the number of<br />

studied diasporas, Khachig Tololyan,<br />

editor of the academic journal Diaspora,<br />

counted “three dozen trans-national<br />

communities…ethnics, exiles, expatriates,<br />

refugees, asylum seekers, labor migrants,<br />

queer communities, domestic service<br />

workers, executives of trans-national corporations,<br />

and trans-national sex workers,”<br />

and the list has grown since then.<br />

The Question of Movement<br />

At the core of every construction<br />

of diaspora is the idea of movement.<br />

All diaspora communities have their<br />

origins in one place and have moved to<br />

several others. The question raised by<br />

identifying so many disparate groups as<br />

diaspora though, is whether all forms of<br />

movement should be thought of as the<br />

same. The key distinction in this debate<br />

is between migration and dispersion.<br />

The primary difference between them is<br />

simple, but significant: volition. Simply<br />

put, the former is something you do, the<br />

latter is something that someone else<br />

does to you.<br />

Dispersion happens in instances<br />

where communities are forced to<br />

move by forces such as war, mass deportation<br />

or, in the case of the African<br />

Diaspora, a massive international slave<br />

trade. Migration, conversely, is largely<br />

a choice. Even in those situations<br />

where lack of employment or resources<br />

cause movement, they don’t force it in<br />

the same way. And while there is unquestionable<br />

trauma in being forced<br />

into migration because of famine or<br />

a weakened economy, it’s a different<br />

trauma than that of surviving a war or<br />

experiencing the Middle Passage.<br />

Translating that distinction to<br />

currently considered diaspora groups,<br />

we see that differences do become<br />

apparent.<br />

The earliest groups to be considered<br />

diaspora, the Jewish, the Greeks,<br />

the Armenians, and the Africans, were<br />

all victims of dispersion of one type or<br />

another. Later groups, such as that of<br />

international sales representatives, or<br />

even Detroit lieutenant governor Garlin<br />

Gilchrist’s laudable Detroit Diaspora<br />

concept, refer to groups that moved of<br />

their own volition. Other characteristics<br />

common to diaspora constructions,<br />

such as a dream of return to the place<br />

of dispersion or the recognition of a<br />

shared culture between members of the<br />

group, may possibly be said to apply, but<br />

certainly not in the same ways.<br />

If there are dispersed communities<br />

that function as diaspora and cannot be<br />

suitably defined by any other term, we<br />

risk losing sight of the unique features<br />

found in those communities by conflating<br />

diaspora with other forms of<br />

movement and migration. This in turn<br />

can lead to misconstrual of the changing<br />

dynamics of diaspora communities and<br />

a misunderstanding of their needs and<br />

goals.<br />

<br />

aphrochic