InsideHistoryDigital

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

the early decades of the nineteenth century, it was safer<br />

to have surgery at home than it was in a hospital, where<br />

mortality rates were three to five times higher than they<br />

were in domestic settings. Those who went under the<br />

knife did so as a last resort, and so were usually mortally<br />

ill. Very few surgical patients recovered without incident.<br />

Many either died or fought their way back to only partial<br />

health. Those unlucky enough to find themselves<br />

hospitalized during this period would frequently fall prey<br />

to a host of infections, most of which were fatal in a preantibiotic<br />

era.<br />

In addition to the foul smells, fear permeated the<br />

atmosphere of the Victorian hospital. The surgeon John<br />

Bell wrote that it was easy to imagine the mental<br />

anguish of the hospital patient awaiting surgery. He<br />

would hear regularly “the cries of those under operation<br />

which he is preparing to undergo,” and see his “fellowsufferer<br />

conveyed to that scene of trial,” only to be<br />

“carried back in solemnity and silence to his bed.” Lastly,<br />

he was subjected to the sound of their dying groans as<br />

they suffered the final throes of what was almost<br />

certainly their end.[3]<br />

As horrible as these hospitals were, it was not easy<br />

gaining entry to one. Throughout the nineteenth<br />

century, almost all the hospitals in London except the<br />

Royal Free controlled inpatient admission through a<br />

system of ticketing. One could obtain a ticket from one<br />

of the hospital’s “subscribers,” who had paid an annual<br />

fee in exchange for the right to recommend patients to<br />

the hospital and vote in elections of medical staff.<br />

Securing a ticket required tireless soliciting on the part<br />

of potential patients, who might spend days waiting and<br />

calling on the servants of subscribers and begging their<br />

way into the hospital. Some hospitals only admitted<br />

patients who brought with them money to cover their<br />

almost inevitable burial. Others, like St. Thomas’ in<br />

London, charged double if the person in question was<br />

deemed “foul” by the admissions officer.[4]<br />

Some hospitals only<br />

admitted patients who<br />

brought with them<br />

money to cover their<br />

almost inevitable<br />

burial.<br />

Before germs and antisepsis were fully understood,<br />

remedies for hospital squalor were hard to come by.<br />

The obstetrician James Y. Simpson suggested an<br />

almost-fatalistic approach to the problem. If crosscontamination<br />

could not be controlled, he argued,<br />

then hospitals should be periodically destroyed and<br />

built anew. Another surgeon voiced a similar view.<br />

“Once a hospital has become incurably pyemiastricken,<br />

it is impossible to disinfect it by any known<br />

hygienic means, as it would to disinfect an old<br />

cheese of the maggots which have been generated<br />

in it,” he wrote. There was only one solution: the<br />

wholesale “demolition of the infected fabric.”[5]<br />

It wasn’t until a young surgeon named Joseph Lister<br />

developed the concept of antisepsis in the 1860s that<br />

hospitals became places of healing rather than<br />

places of death.<br />

1. Adrian Teal, The Gin Lane Gazette (London:<br />

Unbound, 2014).<br />

2. F. B. Smith, The People's Health 1830-1910 (London:<br />

Croom Helm, 1979), 262.<br />

3. John Bell, The Principles of Surgery, Vol. III (1808),<br />

293.<br />

4. Elisabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments<br />

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 13.<br />

5. John Eric Erichsen, On Hospitalism and the Causes<br />

of Death after Operations (London: Longmans,<br />

Green, and Co., 1874), 98.<br />

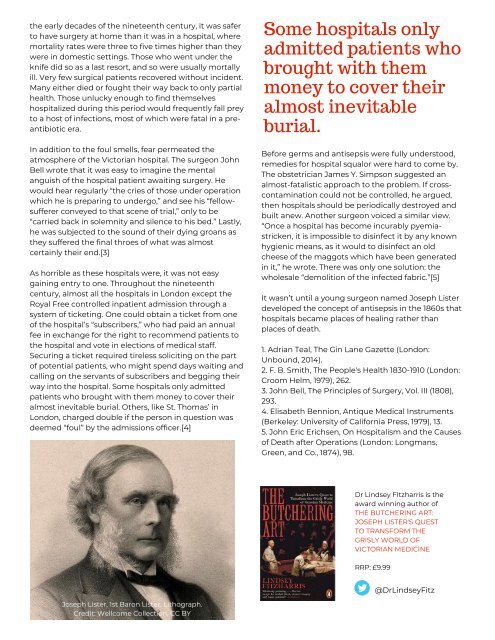

Dr Lindsey FItzharris is the<br />

award winning author of<br />

THE BUTCHERING ART:<br />

JOSEPH LISTER'S QUEST<br />

TO TRANSFORM THE<br />

GRISLY WORLD OF<br />

VICTORIAN MEDICINE<br />

RRP: £9.99<br />

@DrLindseyFitz<br />

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister. Lithograph.<br />

Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY