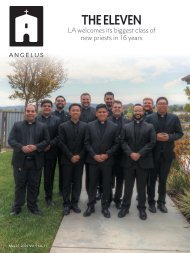

Angelus News | August 2-9, 2019 | Vol. 4 No. 27

A nationwide trend pushing to remove tributes to certain historical figures of U.S. history has seized on a new, unlikely target: the bells lining California’s iconic El Camino Real. The reason? The belief that Spanish missionaries — among them St. Junípero Serra — were oppressors, captors, and even murderers of California’s first peoples. On Page 10, renowned historian Gregory Orfalea examines the most common critiques of the Spanish evangelization of California and makes the case for why the bells represent a legacy of love, not oppression.

A nationwide trend pushing to remove tributes to certain historical figures of U.S. history has seized on a new, unlikely target: the bells lining California’s iconic El Camino Real. The reason? The belief that Spanish missionaries — among them St. Junípero Serra — were oppressors, captors, and even murderers of California’s first peoples. On Page 10, renowned historian Gregory Orfalea examines the most common critiques of the Spanish evangelization of California and makes the case for why the bells represent a legacy of love, not oppression.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

NANCY WIECHEC/CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE<br />

DINA MOORE BOWDEN VIA GREGORY ORFALEA<br />

the population estimate on contact of<br />

225,000.<br />

On several occasions, Serra referred to<br />

the California Indians being “in their<br />

own country.” He almost never referred<br />

to Indians as “barbaros” (“barbarians”),<br />

as others did, but rather “indios,” “gentiles,”<br />

or “pobres.”<br />

In fact, Serra directly suggested that<br />

Spain remove itself from California<br />

if soldier depredations continued. If<br />

the better side of Christianity was not<br />

shown the Indians on a daily basis,<br />

he said, “what business have we … in<br />

such a place?”<br />

Were the missions slavery?<br />

The question arises: Were the missions<br />

slavery? It’s a serious claim, but<br />

it is false. <strong>No</strong> one was forced into the<br />

missions.<br />

This is made clear by the testimony<br />

of Father Pedro Font, diarist of the<br />

second settler expedition into Upper<br />

California, who observed, “The<br />

method of which the fathers observe in<br />

the conversion [of the Indians] is not<br />

to oblige anyone to become Christian,<br />

admitting only those who voluntarily<br />

offer themselves for baptism.” Most<br />

historians ratify this.<br />

There was, however, a catch. Once<br />

one entered the mission he or she<br />

could not leave without permission.<br />

The missions were a community on<br />

a frontier and Indian labor, as well as<br />

Spanish labor, were necessities for a<br />

community’s survival.<br />

We might ponder how many who<br />

came into the mission system understood<br />

this quid pro quo, but there’s<br />

little doubt most fell to the task of<br />

contributing their labor for the food,<br />

clothes, living quarters, and other items<br />

they were given.<br />

Douglas Monroy, a Hispanic-American<br />

historian and author of “The Borders<br />

Within,” calls this “the communitarian<br />

spirit,” and he notes that working<br />

for the common good was not all that<br />

different from the ethic of the Indian<br />

village. Sandos calls the mission Indian<br />

status “spiritual debt peonage,” though<br />

the Indians were given concrete things,<br />

not just spiritual practices.<br />

Most took “leave” to their home<br />

villages for weeks or months. Some,<br />

like the Luiseno of Mission San Luis<br />

Rey, were already in their villages and<br />

commuting to mission work.<br />

There is one undeniable, hard, and<br />

premeditated thing to admit about the<br />

missions: the use of the flog for corporal<br />

punishment for theft, assault, concubinage,<br />

and desertion. That Spanish<br />

civilians and soldiers got the same<br />

treatment is no comfort for those of us<br />

who see such a thing as abhorrent.<br />

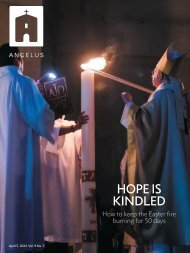

The bell tower of St. Peter’s, Serra’s childhood parish church, in Petra, Mallorca (left) and bells at<br />

Mission San Juan Capistrano (right).<br />

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS<br />

However, a few things need to be said<br />

about this practice. First, whippings for<br />

discipline were common in the 18th<br />

century. Even schoolboys at Eton in<br />

England were caned for infractions,<br />

and their parents paid a fee for it to the<br />

school.<br />

Second, many tribes made prisoners<br />

of war run a gauntlet of beatings, so<br />

such a thing was not entirely strange.<br />

Third, as Father Francis Guest has<br />

written, the Indians were considered<br />

children by the padres, and as such<br />

the flogging was cut in half (12 strokes<br />

at most). Guest also notes that the<br />

punishment was not to be given in<br />

anger and if it were, those who did so<br />

had committed a grave sin and were<br />

subject to punishment themselves.<br />

Serra himself was clearly conflicted<br />

about the practice: “I am willing to admit<br />

that in the infliction of punishment<br />

we are now discussing, there may have<br />

been inequities and excesses on the<br />

part of some Fathers and that we are all<br />

exposed to err in that record,” he wrote.<br />

About this matter, I wrote in my biography<br />

of Serra, “Journey to the Sun:<br />

Junípero Serra’s Dream and the Founding<br />

of California” (Scribner, 2014),<br />

in no uncertain terms: “It was cruel,<br />

a violation of the Fifth Commandment;<br />

Christ accepted the Roman<br />

soldier’s whipping his body, but he<br />

certainly didn’t recommend it. Serra’s<br />

and Lasuen’s arguments for flogging<br />

ultimately ring hollow. They should<br />

have had the wisdom and foresight to<br />

stop it.”<br />

Ultimately, before the mission period<br />

was over, the flogging was outlawed in<br />

1833. Father Francisco Diego at Mission<br />

Santa Clara applauded that “such<br />

punishment as revolts my soul is being<br />

abolished.”<br />

If this were the main story of Serra<br />

and the missions, I would say tear<br />

down the bells. But it isn’t, not by a<br />

long shot.<br />

In his landmark apology to the native<br />

peoples of the Americas in Bolivia in<br />

2015, Pope Francis said, “Where there<br />

was sin — and there was plenty of<br />

sin — there was also abundant grace<br />

increased by the men and women who<br />

defended indigenous peoples.”<br />

As I have indicated, Serra tirelessly defended<br />

the indigenous people against<br />

those who talked as if they were sub-<br />

<strong>August</strong> 2-9, <strong>2019</strong> • ANGELUS • 13