You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PANDAW

Nobody ever said that running river<br />

expeditions would be easy. Those of<br />

our Pandaw Passengers who have<br />

been kind enough to read my rather<br />

exhausting book ‘The Pandaw Story’, which stops<br />

in 2013, will be amused to learn that in the past<br />

years we have had further excitements and<br />

adventures and I could easily pen a sequel.<br />

Since then we have set up in Laos, building<br />

three ships to ply that most difficult of waterways.<br />

With flow rates three times faster than the<br />

Irrawaddy or Lower Mekong, these ships have<br />

engines four times more powerful than ships of a<br />

similar size have on our other rivers. There are<br />

rocks the size of double-decker buses, whirl pools<br />

that might whizz a boat round and round for ever,<br />

and white water that would chill the heart of the<br />

most experienced skipper. Yet we do it, up and<br />

down between Vientiane in Laos, Chiang Saen in<br />

Thailand, touching Burma and on to Jinghong in<br />

China. That is four of the Mekong countries on a<br />

single sailing.<br />

On the Lower Mekong, we sail through<br />

Vietnam and Cambodia (making it six Mekong<br />

countries) where there are now so many river ships.<br />

We remain ahead of the game thanks to the shallow<br />

draft design of our ships reaching parts that others<br />

cannot reach. From the dolphin grounds far up the<br />

river at Stung Treng in Cambodia, to the bird<br />

sanctuaries in the depth of the delta, we remain<br />

pioneers and offer a very different experience.<br />

In the past year we have seen Burma near<br />

collapse as a destination. It’s tragic. I have been<br />

living and working in Burma on and off for thirtyeight<br />

years and never have I experienced a<br />

government so rudderless. There can be no excuse<br />

for what happened in the Arakan. The tragedy is<br />

that the ordinary Burmese are being punished by the<br />

media for the stupidity of their masters. We at<br />

Pandaw have had to downsize our operation by 50%<br />

with painful redundancies; it is very difficult to make<br />

long-serving, loyal crew understand that they are<br />

being let go because of bad press in the West.<br />

On a more positive note for Burma, the<br />

Pandaw Charity thrives with a new central clinic<br />

opened at Pagan in the grounds of a friendly<br />

Buddhist monastery. With over 5000 treatments a<br />

month and a commitment to provide free<br />

medications, we need all the help we can get as<br />

Burma passenger numbers shrink. We are very<br />

grateful for the many donations that made this<br />

new clinic possible and keep all seven running.<br />

India now beckons. We were the first in back in<br />

2009 and ran into troubles. This time our legal setup<br />

is solid whilst the waterways buoyed and charted<br />

which they were not before. Annoyingly, for us and<br />

moreover for the people who booked, we had to<br />

cancel the sailings planned for early <strong>2019</strong> as we had<br />

problems getting the ships out of Burma and over to<br />

India, such is the muddled state into which Burma<br />

has fallen. But all is on track now with the first ships<br />

delivered and ready to start up come September <strong>2019</strong>.<br />

Both our shorter Lower Ganges expedition<br />

through West Bengal or the longer Upper Ganges<br />

from Varanasi to Kolkata are proving very popular<br />

and many departures have been fully subscribed. We<br />

have therefore decided to send a third ship. In 2020<br />

we anticipate opening on the Upper Brahmaputra<br />

sailing as far as Dibrugarh in Eastern Assam thanks<br />

to the ultra-shallow draft of our K class ships.<br />

This magazine brings together the best of the<br />

blogs posted on our website over the past year,<br />

many by Pandaw passengers, and the writing is of<br />

the highest quality, and as with all past <strong>Flotilla</strong><br />

<strong>News</strong> issues, the subjects are of varied interest.<br />

One year ago, we launched the Pandaw Member’s<br />

Club and so far over 10,000 past passengers have<br />

signed up, taking advantage of numerous benefits<br />

and special member’s only discounts in<br />

recompense for past loyalty.<br />

The ‘Pandaw Community’ is essential to our<br />

continuation, and ever since we began nearly 25<br />

years ago our most powerful marketing tool has<br />

been word of mouth. It has even become<br />

generational: I get letters from folk who tell me<br />

their parents came with Pandaw back in the 90s<br />

and now they are following (just like our crews<br />

where there is a growing second generation). I get<br />

letters too from regulars who have been with us a<br />

dozen times! Some say they come not for the<br />

destinations but for the atmospheric ships and<br />

their friendly crews. Others eagerly await the next<br />

Pandaw adventure into the unknown, with all that<br />

can go wrong!<br />

On behalf of all our crew members thank you<br />

for your past and continued support of Pandaw.<br />

We warmly look forward to taking care of you on<br />

future adventures. If you have not been with us<br />

before, there is much in store, but, be warned,<br />

these are not ‘cruises’ in any sense at all. π<br />

Pandaw Founder<br />

3

Taj Mahal<br />

Kolkata<br />

Kalna<br />

Andaman Islands<br />

Brahmaputra<br />

Varanasi

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PA N DAW.COM<br />

NEW EXPEDITIONS WITH PANDAW<br />

Diburgarh<br />

Upper Ganges<br />

Farakka<br />

Guwahati<br />

Upper Brahmaputra<br />

Lower Ganges<br />

Varanasi<br />

GANGES RIVER<br />

The Ganges River is the 34th longest river in the world at<br />

2,620km, flowing down through the Himalayas to form the<br />

Gangetic Plain of North India and eventually to discharge into<br />

the Bay of Bengal through Bangladesh. The Hooghly river<br />

connects the Ganges river to Calcutta with a ship lock as part of<br />

the Farakka Barrage that diverts water away from Bangladesh. The<br />

Ganges river is the cradle of Indian civilisation and is sacred to<br />

Hindus. To bathe in the waters of the “Holy Ganga” is a form of<br />

purification, and to be cremated at the Ghats [stepped riverside<br />

terraces] of Varanasi is the ambition of every living Hindu. The<br />

river was used for navigation in British colonial times with<br />

steamer services between Kolkata, Patna and even further<br />

upriver. Massive irrigation schemes later diverted waters and the<br />

construction of railways, and later roads with low bridges,<br />

effectively killed river transportation and the navigation channels<br />

silted up.<br />

In recent years much has been done to improve navigation<br />

and Patna can be reached year-round, and at certain times<br />

Varanasi too. A river cruise on the Ganges river is really the only<br />

sensible way to see India avoiding now-congested roads and all<br />

the other inconveniences of travelling today in India. There is<br />

much to see along the way – historically, culturally and for bird<br />

and wild life. This is a river that offers rich experiences. π<br />

Kolkata<br />

B AY O F<br />

B E N G A L<br />

BRAHMAPUTRA RIVER<br />

India's Brahamputura River is the 29th longest river in the world<br />

at 2,948 km long, and has a discharge of 19,200 cubic litres per<br />

second which puts northern India's great waterway in the top 10<br />

when it comes to volume. Indeed, this is a massive waterway,<br />

being the only river on Earth clearly visible from the Moon during<br />

the Apollo missions. Flowing down from central Tibet through<br />

the legendry Tsangpo gorges, the Brahamputura river opens out<br />

as it enters Assam to flow across that state and then through<br />

Bangladesh to flow out through the vast Sunderbunds Delta,<br />

merging with the Ganges River, as they discharge into the Bay of<br />

Bengal.<br />

The Brahamaputra river may be little-navigated today, but in<br />

colonial times steamer services operated as far as Dibrugarh. The<br />

river in places can be up to 20 miles wide and in the monsoon it<br />

floods the entire Assam plain. Indeed, East Bengal is not called<br />

“the wettest place on the planet” for nothing – it literally does<br />

have the world’s highest rainfall.<br />

The river is so vast that any river cruise expedition undertaken<br />

here can be movingly wondrous, as you pass through this great<br />

emptiness of water, sand and shoal. There is not a lot of human<br />

activity on the riverbank, but that means the wild life and bird<br />

life are profuse. π<br />

ANDAMAN ISLANDS<br />

The Andaman Sea, glimpsed at from the sandy shores of Phuket and southern Thailand, is<br />

traversed only by the most intrepid of yachtsman. The sea is perhaps the most exquisite corner<br />

of the Indian Ocean, stretching five hundred miles from South East Asia to the Andaman and<br />

Nicobar chain.<br />

From Burma’s Mergui Archipelago to India’s Andamans there is a most extraordinary<br />

ethnographic mix not to mention biodiversity and marine life. It is also very beautiful with many<br />

uninhabited islands ringed by dazzling white sands.<br />

For the first time ever, Pandaw will be offering two ten night expeditions across this sea<br />

exploring both the Mergui and Andaman archipelagos. Both areas have until recently been<br />

closed by their respective governments and such an expedition would have been unimaginable.<br />

For those with less time, we also offer a small number of seven night expeditions exploring<br />

the Andaman archipelago flying in and out of airports on mainland India. π<br />

Andaman<br />

Islands<br />

Port Blair<br />

Diglipur<br />

A N D A M A N<br />

S E A<br />

FOR MORE INFORMATION CHECK ONLINE AT PANDAW.COM/INDIA 5

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

N E W F O R 2 0 1 8<br />

NEW ADDITION<br />

TO THE FLEET<br />

R V S A B A I D E E PA N D AW<br />

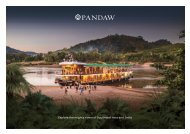

We are excited about the addition of a seventeenth ship to<br />

the Pandaw <strong>Flotilla</strong>, which was completed in Laos in<br />

October 2018 to meet demand on our very popular Laos<br />

to China route across Yunnan.<br />

In true Pandaw style, this double decked vessel is designed to meet the<br />

navigational challenges of shooting rapids in the Laos gorges and sailing<br />

through shallow waters all the way to China.<br />

The SABAIDEE, like her sister ships, belongs to Pandaw’s unique<br />

ultra-shallow draft K-class. These were pioneered in Burma by the<br />

Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong> Company in the 1880s as the shallowest draft vessels<br />

of such a size on the planet, which they remain so today. This means<br />

that year-round they can sail all the way up to Varanasi and beyond.<br />

Being only twin-decked, they can also get under low bridges!<br />

The SABAIDEE has just fourteen classic Pandaw staterooms; eight<br />

on the main deck and six on upper deck as well as an open plan saloon<br />

with flexible indoor or outdoor dining. The SABAIDEE has been<br />

handcrafted to our usual level of excellence in teak and brass and provides<br />

all the comforts of the personalised service our guests expect. π<br />

Vessels Name . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Sabaidee Pandaw<br />

Type . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Inland Waters Navigation<br />

Year built . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2018<br />

Class . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Laos Class<br />

Flag . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Laos<br />

HP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2x 350<br />

Length . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41m<br />

Beam . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8m<br />

Depth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.2m<br />

Draft . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.0m<br />

Airdraft . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8m<br />

PAX . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24<br />

6

W W W . P A N D A W . C O M<br />

Enjoy no single supplement on selected dates

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands<br />

(ANI) refer to two island groups –<br />

the Andaman Islands and the<br />

Nicobar Islands – located east of<br />

the Indian mainland in the Bay of<br />

Bengal. Together, the two islands consist of<br />

over 500 islets, and are separated by the Ten<br />

Degree Channel spanning 150 km. An Indian<br />

territory covering approximately 3,185 square<br />

miles, the islands have caught in recent years<br />

the attention of leisure tourists drawn to their<br />

stunning scenic beauty and interesting history.<br />

A BRIEF HISTORY<br />

OF THE ISLANDS<br />

Archaeological evidence from around 2,200<br />

years ago indicates that the indigenous<br />

Andamanese people may have been cut-off<br />

from other populations during the Middle<br />

Paleolithic era, and diversified into different<br />

territorial groups. Meanwhile, people of<br />

various backgrounds occupied the Nicobar<br />

Islands, and over time, united into two groups<br />

speaking Shompen and Mon-Khmer<br />

languages.<br />

There are more theories than facts about<br />

the origin of ANI. Ancient Indian epic poem<br />

Ramayana contains references to Lord Rama<br />

seeking to bridge the sea to find his kidnapped<br />

wife Sita with the help of monkey-god<br />

Hanuman, and that it was achieved by<br />

grouping islands whose inhabitants were<br />

known as Handuman, from whom the name<br />

‘Andaman’ was derived.<br />

Another theory brings in a Malay<br />

association, claiming that ancient Malays<br />

owned slaves on the ‘island of Handuman’ and<br />

travelled here by sea to capture aboriginals and<br />

sell them. Another reference is found in the<br />

work of Chinese Buddhist pilgrim I-tsing, who<br />

embarked on a voyage to India in 671 A.D. and<br />

called the islands ‘the islands of cannibals’ or<br />

‘Andaban’, even describing the place in detail,<br />

including the barter of coconut for iron.<br />

Marco Polo stopped at the Andamans en<br />

route his voyage to China in 1290 A.D. In his<br />

book Oriente Poliano or The Travels of Marco<br />

Polo, the legendary traveller speaks of the<br />

‘Angamanain’ island whose people he<br />

describes as having ‘heads, teeth and eyes like<br />

dogs’ and the propensity to eat everyone they<br />

can catch. He also mentions that the islanders<br />

don’t have a king, and subsist on flesh, milk,<br />

rice and fruits that he has never seen before.<br />

The Chola Empire, one of the longestruling<br />

dynasties ever, whose antiquity is<br />

unknown, used the islands as a strategic naval<br />

base to combat the Sriwijaya Empire (modern<br />

day Indonesia). The Cholas called the islands<br />

Ma-Nakkavaram or ‘naked land’ as well as<br />

Tinmaittivu or ‘impure islands’. The islands<br />

also served as a maritime base for ships<br />

8

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

ABOVE The Andaman<br />

Explorer cruising the<br />

Andaman islands<br />

RIGHT ABOVE<br />

View of Port Blair<br />

RIGHT BELOW<br />

Cellular Jail at<br />

Port Blair<br />

belonging to the Maratha Empire. Navy<br />

Admiral Kanhoji Angre bolstered naval<br />

supremacy by setting up base on the islands.<br />

Maratha rulers also attached the islands to<br />

India, with the ANI today being one of the<br />

seven union territories of the country.<br />

In 1755, the Danish East India Company<br />

made the Nicobar Islands a Danish colony,<br />

changing their name to New Denmark and<br />

later Frederick’s Islands. Bouts of malarial<br />

outbreaks caused a change of heart and Danish<br />

colonizers eventually bid adieu to the islands<br />

in 1848.<br />

The British East India Company found the<br />

islands ideal to hold mutineers of the Indian<br />

Rebellion, a major but unsuccessful rebellion<br />

against the British rule. In 1858, Dr. James<br />

Walker landed in Port Blair on a frigate hauling<br />

hundreds of convicts. Taking advantage of the<br />

heavy rainfall and being aware that the<br />

Andamans were connected to Burma by land,<br />

the convicts make attempts to escape. The<br />

islanders killed many of the convicts, captured<br />

men were hanged, and some who had fled to<br />

the jungles surrendered. Among many more<br />

mutineers who were packed off to the islands,<br />

some died of malaria and dysentery. Walker<br />

was admonished and instructed to make peace<br />

with the aborigines and allow well-behaved<br />

convicts to relocate their family from India to<br />

the islands.<br />

The penal settlement gradually expanded.<br />

Forests were cleared to plant rice, vegetables,<br />

coconut trees and bananas. In 1896,<br />

construction of the Cellular Jail began. It was<br />

initially envisioned to architecturally resemble<br />

a prison in Pennsylvania but later inspired by<br />

the HM Prison Pentonville, the Category B<br />

men’s prison operated by Her Majesty’s Prison<br />

Service. Nearby, a church, mess, barracks and<br />

a residence for the Chief Commissioner were<br />

built, followed by tennis courts, a golf course<br />

and football grounds. A school for convicts’<br />

children also became a part of the district.<br />

Cellular Jail had 698 cells designed to hold<br />

mutineers in solitary confinement, and housed<br />

such notable dissidents as Vinayak Damodar<br />

Savarkar, Yogendra Shukla and Batukeshwar<br />

Dutt.<br />

In 1868, over 200 inmates tried to escape<br />

but were captured soon after. Walker ordered<br />

some to be hanged. In 1933, inmates began a<br />

hunger strike opposing the treatment of<br />

prisoners; three among them died from forcefeeding.<br />

After intervention from Mahatma<br />

Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore, inmates<br />

were repatriated from the jail in 1938.<br />

Cellular Jail is one of the island’s key<br />

modern-day tourist attractions. It resembles a<br />

wheel with the central tower as the main axle<br />

and seven wings as spokes. Its Panopticon<br />

design scheme allowed for all inmates to be<br />

observed by a single guard without prisoners<br />

able to decipher whether or not they are being<br />

watched.<br />

During the Second World War, the islands<br />

caught the attention of the Japanese because<br />

they could hold a large number of ships. By that<br />

time, only one British Infantry company was<br />

stationed at Ross. Between 1941 and 1942, the<br />

Imperial Japanese Army Air Service began air<br />

raids on Rangoon. After the fall of Burma, the<br />

garrison convicts, settlers and officials were<br />

evacuated. Only a few British officers and those<br />

who had no home elsewhere chose to stay back.<br />

One of the officers was executed by the<br />

Japanese. During this time, Netaji Subhash<br />

Chandra Bose, a freedom fighter who<br />

collaborated with Imperial Japan and Nazi<br />

Germany to drive the British out of India,<br />

visited the islands and offered the moniker<br />

Swaraj-dweep’ or self-rule island.<br />

After India and Burma gained<br />

independence, the British moved to resettle<br />

Anglo-Indians and Anglo-Burmese on the<br />

islands. Their plan failed and in 1950, the<br />

Andaman and Nicobar Islands became a part<br />

of India and a union territory in 1956.<br />

9

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

ABOVE<br />

Group of<br />

Andaman men<br />

and women in<br />

costume,<br />

catching turtles<br />

ORIGINAL INHABITANTS<br />

OF THE ISLANDS<br />

Four Negrito and two Mongoloid tribes are the indigenous<br />

inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, having lived here for<br />

30,000-40,000 years. Settlers to the islands arrived in the<br />

1950s, after being persuaded by the Indian government to<br />

inhabit large swathes of unoccupied land, with 10 acres of<br />

free land as inducement.<br />

Negritos comprise different ethnic groups inhabiting,<br />

besides ANI, Peninsular Malaysia, Southern Thailand and<br />

Philippines. They are characterized by their small stature<br />

and dark skin. The Negritos of ANI are claimed to resemble<br />

African pygmies. The Negrito tribes of ANI are the Great<br />

Andamanese, Jarawa, Onge and Sentinelese.<br />

The Great Andamanese originally consisted of ten<br />

tribes, each with its own language and population of 200-<br />

700 people. The British invasion decimated large numbers<br />

of tribe members and in the 1970s, the Indian government<br />

moved survivors to the Strait Island, providing them<br />

shelter, food and clothing. Less than 60 Great Andamanese<br />

people exist today.<br />

The Onge population has also declined and the<br />

territories they occupied on Little Andaman Island have<br />

also shrunk, now shared with settlers from Bangladesh,<br />

India and the Nicobar Islands. And although their<br />

settlements fell prey to the Tsunami’s fury in 2004, no tribe<br />

member lost their life. After feeling the tremors and<br />

watching water levels recede, the Onge made their way<br />

inland and escaped the waves.<br />

The Onge decorate their faces with white clay and chew<br />

bark to impart a reddish hue to their teeth. While they hunt<br />

for wild boar and collect honey, for the large part, the Onge<br />

rely on the Andaman authorities for food and commodities.<br />

The Sentinelese are one of the world’s last uncontacted<br />

tribes, and live on the small North Sentinel island. They are<br />

highly resistant to human contact and have made their<br />

distaste for outsiders apparent in both harmless and lethal<br />

ways. But the Sentinelese seem to be doing well – they<br />

enjoy good health and photographs have shown children<br />

and pregnant women. However, despite thriving in<br />

isolation and surviving the tsunami, they are at a risk of<br />

falling prey to diseases to which they lack immunity, which<br />

also makes contact with them a dangerous proposition.<br />

Like the Sentinelese, the Jarawa population is selfsufficient,<br />

although it does not live in extreme isolation. A<br />

few tribe members first ventured out of the forest in the<br />

late nineties to explore nearby towns, and by the 2000s,<br />

authorities announced that the Jarawas would be free to<br />

decide their own future and won’t be settled forcibly to<br />

bring them into the mainstream.<br />

Today, about 470 Jarawas co-exist with settlers. While<br />

most prefer to hunt and live amongst their own, a few can<br />

be seen walking along roads and interacting with tourists.<br />

Still, their survival is threatened by illegal fishing and<br />

gathering by poachers. Concerns have also been expressed<br />

over the threat posed to the Jarawas by the encroaching<br />

Andaman Trunk Road.<br />

The Nicobarese are one of the two Mongoloid tribes in<br />

the ANI. A designated Scheduled Tribe, their population is<br />

estimated at 30,000. They depend on horticulture and<br />

receive free education from the government. The Shompen<br />

tribe, also a designated Scheduled Tribe, inhabits the<br />

interior of Great Nicobar Island, and has a predominantly<br />

hunting-gathering culture, and some pig-rearing and<br />

horticultural activities. Relatively isolated, the tribe has a<br />

high male to female ratio, which has resulted in marriage<br />

by capturing women of different groups within the tribe,<br />

and a large number of unmarried adult males.<br />

10

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

ABOVE<br />

Havelock<br />

Island Beach<br />

RIGHT<br />

Andaman<br />

Explorer<br />

FLORA AND FAUNA<br />

The islands are home to an impressively rich variety of flora<br />

and fauna. Their location in eastern Indian Ocean assures a<br />

warm tropical climate ranging from 22°C - 30°C, while<br />

annual rainfall ranges from 3,000 -3,800 millimeters. Close<br />

to 90% of the islands are forested, boasting more than 2000<br />

plant species, many of which are endemic to the territory.<br />

Scattered with mangrove and coastal forests, the islands’<br />

trees can reach heights of 40-60 meters.<br />

In the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami,<br />

Nicobar Islands lost more than 70% of their mangrove cover.<br />

However, researchers say that new habitats can potentially<br />

generate to regrow mangroves and new, unrecorded<br />

mangrove species.<br />

The islands’ nine national parks and many wildlife and<br />

marine sanctuaries offer an opportunity to experience the<br />

diverse ecosystem. Whether you want to observe wildlife<br />

in their natural habitat or view innumerable species of<br />

butterflies, ANI has you covered.<br />

The islands are also a bird-watcher’s paradise. Among the<br />

200+ bird species found here are the Narcondam hornbill,<br />

Andaman wood pigeon, Andaman scop’s owl, fulvous<br />

breasted woodpecker and the blue-eared kingfish. Rain forests<br />

on the Andaman Islands are home to 45 reptile species,<br />

thirteen of which are endemic. The Malayan Box Turtle on the<br />

Nicobar Islands is the world’s only non-marine turtle. Ten of<br />

the forty species of snakes found here are venomous,<br />

including the Andaman Cobra, Andaman Krait, Pit Vipers,<br />

King Cobra and sea snakes.<br />

Of the 62 mammal species on the island, 32 are<br />

endemic, including the Andaman wild pig, crab-eating<br />

macaque and Andaman masked palm civet.<br />

The Indian government recently modified an earlier<br />

order that made it mandatory for foreign tourists to ANI<br />

to register with the Foreigners Registration Officer within<br />

24 hours of their arrival. The white sand beaches of<br />

Andaman have become a favorite tourist haunt in recent<br />

years; while some are buzzing with tourist activity, you will<br />

also find a few serene beaches that provide a private and<br />

tranquil experience.<br />

EXPLORE THE ANDAMAN<br />

ISLANDS ABOARD THE MY<br />

ANDAMAN EXPLORER<br />

Your expedition aboard the Andaman Explorer will take<br />

you through the South Andaman Island with its beautiful<br />

ferns and orchards, Havelock and Lawrence Islands that<br />

house some of ANI’s best beaches for swimming and<br />

snorkeling, Northern Andaman Island where you can<br />

interact with local communities and partake in folk dances<br />

and workshops, Mayabunder where you can gain insights<br />

into Karen cultural life, and Rangat Bay and Long Island<br />

whose virgin beaches promise an idyllic experience. π<br />

11

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

A trip up the<br />

Chindwin River<br />

BY<br />

GENERAL<br />

MIKE<br />

RIDDELL<br />

WEBSTER<br />

The Japanese first bombed<br />

Rangoon on the 23rd of<br />

December 1941. Between then<br />

and late April/early May 1942,<br />

the British were to conduct a<br />

difficult, demoralising and dangerous retreat<br />

of some 900 miles as they fell back to the<br />

Imphal Plain, nestled in the hills of North East<br />

India, pursued every step of the way by the<br />

relentless Japanese onslaught. It was to be the<br />

longest retreat in British military history. And<br />

it was not just the Army. The whole British<br />

and Indian expatriate communities were on<br />

the move. Whilst many opted for routes west<br />

over the Arakan or north to Bhamo and<br />

beyond, many chose to aim for Imphal and<br />

travel up the Chindwin valley; it is estimated<br />

that a total of 500,000 made it to India, with<br />

10-50,000 perishing on the way. The route to<br />

Imphal takes in some 250 miles of the<br />

Chindwin River, traveling upstream from its<br />

confluence with the Irrawaddy River to the<br />

town of Sittaung, from where it is possible to<br />

cross the Burma/India border at Tamu.<br />

ll forms of transport were pressed into<br />

service for this chaotic move with a hostile<br />

force snapping at their heels: cars, lorries,<br />

elephants and boats of the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong><br />

Company, for which this was to be their last<br />

mission before being scuttled. The story<br />

resonates as one of a desperate, moralecrushing<br />

journey, with glimpses of humour,<br />

self-sacrifice and extraordinary courage.<br />

The military forces opposed to the<br />

Japanese consisted of the 40,000 strong<br />

British Burma Corps (or Burcorps),<br />

commanded by Lieutenant General William<br />

Slim, and three Chinese Armies, with a total<br />

strength similar to Burcorps. At first, these<br />

forces acted in concert, but the Chinese were<br />

to retreat on the northern route towards<br />

Bhamo as they made for China rather than<br />

India. As a result they played no part in the<br />

retreat up the Chindwin, once north of<br />

12

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

ABOVE Lieutenant<br />

General William Slim<br />

Irrawaddy/Chindwin confluence.<br />

To travel the Chindwin River, whose valley<br />

was one of the main arteries of the retreat, is<br />

not possible without reflecting on the horrors<br />

of that journey. As the retreat was taking part<br />

in the early months of the year, the weather<br />

was dry and hot. Water levels on the<br />

Chindwin would have been dropping and, by<br />

the time Burcorps were crossing the<br />

Irrawaddy in late April 1942, the river levels<br />

would have been very low. So low, indeed, that<br />

the Chindwin itself was ruled out as the main<br />

route for the withdrawal; the route would now<br />

have to be along jungle tracks as Burcorps<br />

found their way to Imphal.<br />

As Burcorps attempted to cross the<br />

Irrawaddy at Sameikkon, west of Mandalay, it<br />

became clear that the promised ferries were<br />

not there. Simultaneously, the Irrawaddy<br />

<strong>Flotilla</strong> Company was beginning to scuttle<br />

some of its river fleet at Mandalay. John<br />

Morton, the manager of the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong><br />

Company, was in Mandalay; his diary for the<br />

28th of April records:<br />

"Mandalay was evacuated yesterday, the<br />

IF being the last to go. The Army is retreating<br />

up the Chindwin. Our men won't be many<br />

days at Monywa and I expect them to retire<br />

up the river and so through to Manipur.<br />

Macnaughtan has been at Sameikkon (below<br />

Mandalay) ferrying the Army across the<br />

Irrawaddy. I have a guarantee from General<br />

Slim that he and the crews of the steamers<br />

there will be taken safely to Monywa.<br />

We are being chased out even quicker<br />

now than was expected and I have orders for<br />

more sinkings here at Kyaukmyaung. There<br />

are over two hundred of our fleet sunk at<br />

Mandalay. Imagine how I felt drilling holes in<br />

their bottoms with a bren gun."<br />

Once the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong> boats,<br />

commanded by <strong>Flotilla</strong> Assistant John<br />

Macnaughtan, now a Lieutenant in the Burma<br />

RNVR, had ferried elements of Burcorps<br />

across the Irrawaddy, they did indeed retire up<br />

the river and were to be instrumental later on<br />

in the retreat.<br />

Others of Burcorps managed to cross the<br />

Irrawaddy by the Ava Bridge, nearer to<br />

Mandalay and, once the entire Corps were<br />

west of the Irrawaddy, the Ava Bridge was<br />

blown at midnight on the 30th of April<br />

signalling, in the words of General Slim,<br />

"that we had lost Burma".<br />

Travelling by car from Pagan to our<br />

embarkation point at Monywa provided a<br />

number of opportunities to reflect on that epic<br />

military retreat. As we flicked effortlessly<br />

across the Irrawaddy on a new bridge at<br />

Pakokku, just south of the Chindwin/<br />

Irrawaddy confluence, we pondered that<br />

altogether more complicated crossing by ferry<br />

of an Army Corps. Driving up an almost<br />

empty road into Monywa from the south<br />

13

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

reminded us of those soldiers of the Glosters<br />

(The Gloucestershire Regiment) and Royal<br />

Marines, who had been holding the town in<br />

1942. During the night of 30th of April/1st of<br />

May, there was much confused fighting. It<br />

was thought that the Japanese had taken the<br />

town, and the General Officer Commanding<br />

1st Burma Division, Major General Bruce<br />

Scott, found himself fighting for his life as his<br />

headquarters was overrun. Reinforced early<br />

on the 1st of May by six or seven hundred<br />

troops who had come up the Chindwin, the<br />

Japanese took Monywa later that day and,<br />

despite a counter-attack and some fierce<br />

fighting on the 2nd of May, the town<br />

remained in Japanese hands. The capture of<br />

this town confined the British to their land<br />

route and gave the Japanese access to the<br />

main waterway.<br />

Today Monywa is peaceful, has a large<br />

bridge crossing the Chindwin and is a hub of<br />

river transport. How extraordinary is it, to be<br />

boarding the graceful Kalay Pandaw in bright<br />

sunshine and being greeted with fruit juices<br />

and lunch rather than mortars and bullets!<br />

For the next two days we followed the<br />

footsteps of <strong>Flotilla</strong> Assistant Macnaughtan<br />

and his doughty men. In the most<br />

tremendous comfort, we literally watched<br />

Burmese life pass us by. In late January the<br />

river levels are already low, making our<br />

progress slow as our crew checked the depths<br />

with their painted bamboo depth finders. Side<br />

trips on mountain bikes took us to some<br />

wonderful Burmese villages, considerably less<br />

encumbered by the piles of plastic found in<br />

the more popular parts of Burma. Highlights<br />

included calling in at a small village called<br />

Mingin, where our host and Pandaw founder,<br />

Paul Strachan, knows the Abbot. The village<br />

was wonderful – not a shred of plastic<br />

anywhere as the Abbot exerted his influence<br />

and called for order. Rather, water fights<br />

between playful locals as they cleaned a<br />

pagoda in advance of a religious ceremony,<br />

and solar power plants and batteries were the<br />

order of the day.<br />

The next early morning presenteda very<br />

real link back to that awful retreat of 1942. At<br />

about 0730, the little bay of Shwegyin came<br />

into view. Known as "The Bowl", Shwegyin is<br />

just that: a large area surrounded by hills<br />

about 200 feet high. It was in this bowl that<br />

the Army gathered as it came out of the<br />

jungle in search of somewhere to cross the<br />

Chindwin. The surrounding hills were<br />

picketed as the last line of defence from the<br />

pursuing Japanese and there was fierce<br />

fighting as the Japanese attempted to cut<br />

Burcorps off completely from further retreat.<br />

Here it was that <strong>Flotilla</strong> Assistant<br />

Macnaughtan had gathered his little fleet of<br />

six "S" class sternwheeler steamers to help in<br />

the evacuation of Burcorps across the river to<br />

the town of Kalewa, six miles upstream.<br />

Today, there is a shiny new bridge which<br />

crosses the river at Kalewa, but in 1942 the<br />

difficult jungle track reached the Chindwin at<br />

Shwegyin and its jetty. Doubtless the legacy of<br />

the teak traders, who would have used the<br />

"chaung" or stream that issues into the<br />

Chindwin at this point, the track and jetty was<br />

the only sensible place for loading troops. The<br />

six Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong> ships worked tirelessly,<br />

in increasingly dangerous circumstances to<br />

evacuate troops and refugees. Light vehicles<br />

were also loaded and transported, but the<br />

tanks had to be abandoned. Unlike our<br />

luxurious Kalay Pandaw, those <strong>Flotilla</strong> ships<br />

were steam driven and soldiers boarding had<br />

to bring a log with them to fuel the boilers,<br />

rather than carrying a ticket.<br />

A boom had been established across the<br />

Chindwin to stop the Japanese moving up the<br />

river by boat, and this measure was successful<br />

until it was broken by shelling on the 7th of<br />

May. Despite breaching the boom, the<br />

Japanese failed to get sufficiently far up the<br />

river to cut off the British crossing.<br />

Looking around Shwegyin today, little<br />

seems to have changed and it is all too easy to<br />

imagine the fighting, the chaos as troops were<br />

loaded onto boats, and the suppressed air of<br />

urgency; it must have been something of an<br />

inland Dunkirk. General Slim described it as<br />

"one huge bottleneck". Loading the <strong>Flotilla</strong><br />

ships was slow, as they took on board their<br />

cargo of 5-600 tightly packed troops. Slim<br />

recalls hundreds of civilian vehicles in "The<br />

Bowl" and, although there is nothing left now,<br />

it is not difficult to picture dozens of<br />

abandoned vehicles getting in the way as their<br />

owners jostled for places on board a steamer.<br />

The Japanese finally forced their way into "The<br />

Bowl" on the 10th of May and the remaining<br />

troops had to march up the east bank of the<br />

river until they were opposite Kalewa, although<br />

the redoubtable Chief Engineer Hutcheon,<br />

who was by now captaining an Irrawaddy<br />

<strong>Flotilla</strong> ship, managed to evacuate about 2,400<br />

troops from a creek about half way between<br />

Shwegyin and Kalewa. Hutcheon's fellow<br />

Chief Engineer, John Murie, was awarded a<br />

Military Cross in the field by General<br />

Alexander on the 16th of May for his part in<br />

maintaining the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong>'s<br />

contribution to the evacuation. The history of<br />

that evacuation is still sharp in the folklore of<br />

the locals at Shwegyin. We met one resident<br />

who had a Japanese bayonet and another<br />

14

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

whose mother had learnt to speak Japanese<br />

when she was six, during the Japanese<br />

occupation of the following two years.<br />

Making our way along that final six<br />

miles upstream to Kalewa, it was also easy<br />

to see how troops would have been landed,<br />

as they prepared for the start of their long<br />

march up the infamous Kabaw Valley to<br />

Manipur and relative safety. The retreat<br />

had, for some time, been a race against<br />

three competing dangers; the Japanese,<br />

reducing rations and the rains. The<br />

Japanese had been held just enough to<br />

allow the evacuation and rations had been<br />

cut time and again. But now the rains<br />

arrived. On the 12th of May, they broke in<br />

full fury, rendering marching conditions<br />

indescribable and the going underfoot<br />

treacherous, but they stopped the Japanese.<br />

That day the Japanese occupied Kalewa,<br />

but came no further, allowing Burcorps to<br />

struggle their way back over the hills to<br />

Manipur. As Slim watched the last of them<br />

arrive in Imphal, he wrote:<br />

On the last day of that nine hundred<br />

mile retreat I stood on the bank beside the<br />

road and watched the rearguard march into<br />

India. All of them, British, Indian, and<br />

Gurkhas, were gaunt and ragged as<br />

scarecrows. Yet, as they trudged behind<br />

their surviving officers in groups painfully<br />

small, they still carried their arms and kept<br />

their ranks, they were still recognisable as<br />

fighting units. They might look like<br />

scarecrows, but they looked like soldiers<br />

too."<br />

The Japanese were to remain where<br />

they had stopped for nearly two years, until<br />

they invaded India in March 1944. Starting<br />

with the huge struggles for the Imphal<br />

Plain and Kohima, Slim and his<br />

"forgotten" Fourteenth Army were to<br />

defeat the Japanese in a series of epic<br />

battles, ultimately forcing the Japanese<br />

back into Burma. The British finally<br />

returned to the Chindwin in early<br />

December 1944 and crossings followed at<br />

Sittaung, Mawlaik and Kalewa as the<br />

precursors to the re-conquest of the whole<br />

of Burma, all of which is another tale of<br />

extraordinary ingenuity, endurance and<br />

courage.<br />

As we travelled the Chindwin in luxury,<br />

admiring its glorious beauty, it behove us<br />

all to spare a thought for those of Burcorps<br />

and, later, those of the Fourteenth Army<br />

who had fought so hard to ensure that<br />

Burma was liberated from Japanese<br />

occupation. I certainly raised my glass to<br />

them all as we sailed so comfortably past<br />

the sites of their struggles. Not for us was<br />

the Fourteenth Army forgotten. π<br />

15

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

BY THE OLD<br />

MOULMEIN<br />

PAGODA<br />

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder<br />

Kipling only spent a day<br />

in Moulmein where he<br />

disembarked for a day's<br />

tour on his way to Japan<br />

in 1889. Of course, the poem<br />

makes geographical nonsense, as<br />

Moulmein is nowhere near the<br />

Irrawaddy River and the paddles<br />

chunking to Mandalay, which he<br />

never visited. Moulmein sits on<br />

the estuaries of three rivers: the<br />

Salween, the Gyaing and the<br />

Ataran that spread out like a great<br />

map when viewed from the Kyaik-tun hilltop<br />

pagoda.<br />

Kipling later wrote that that day he fell in love<br />

with a Burmese maiden whilst visiting the town's<br />

main pagoda. "Only the fact of the steamer<br />

departing at noon prevented me from staying at<br />

Moulmein forever...". We have to thank this<br />

nameless belle who was an inspiration for one of<br />

the greatest poems in the English language.<br />

Ironically, the words 'Kipling' and 'Burma' became<br />

synonymous yet he knew the country little,<br />

jumping off the steamer for a quick sightseeing in<br />

Rangoon and Moulmein. Despite the brevity of his<br />

visit, no European ever captured the magical<br />

essence of Burma better than Kipling, whether in<br />

the 1890s or today.<br />

16<br />

“<br />

BY THE old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin' lazy at the sea,<br />

There's a Burma girl a-settin', and I know she thinks o' me;<br />

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say:<br />

"Come you back, you British soldier; come you back to Mandalay!"<br />

Come you back to Mandalay,<br />

Where the old <strong>Flotilla</strong> lay:<br />

Can't you 'ear their paddles chunkin' from Rangoon to Mandalay?<br />

On the road to Mandalay,<br />

Where the flyin'-fishes play,<br />

An' the dawn comes up like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay!<br />

by Rudyard Kipling<br />

”<br />

Moulmein was a British creation following the<br />

First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824 when the<br />

territories of Tenasserim and the Arakan were<br />

ceded to the British. The choice was strategic, as<br />

opposite was the Burmese town of Martaban,<br />

which had been an important provincial capital for<br />

centuries, sitting at the mouth of the great<br />

Salween, the longest river in Burma. Strategically<br />

with rivers on two sides, the northern point<br />

opposite Martaban was called Battery Point, with<br />

its guns pointing across the river at Burmese<br />

territory.<br />

The East India Company absorbed this new<br />

territory with some degree of reluctance, as it<br />

would be costly to garrison and administer with<br />

little potential for profit. Colonel Bogle, the first<br />

Civil Commissioner (equivalent to<br />

a governor), built himself a palatial<br />

mansion called Salween House<br />

set in a spacious park on one of<br />

the hills. Later this was considered<br />

too grand for a civil servant's<br />

residence and it was turned into<br />

the court house and town offices.<br />

The Board of Directors in Calcutta<br />

were soon proved wrong and<br />

Moulmein developed into an<br />

important economic hub: initially<br />

teak extraction, then obviously<br />

ship building taking advantage of abundant<br />

timber; later, rubber planting and tin mining.<br />

John Crawfurd, a native of Islay who had been<br />

an army doctor and former 'resident' at the Court<br />

of Ava and Dr Wallick, the superintendent of the<br />

Botanical Gardens in Calcutta, travelled on the<br />

Diana, the first steam paddler in Burma that had<br />

been brought over from Bengal in 1824 for the<br />

Anglo-Burmese War. Despatched to Moulmein she<br />

made an expedition up the Ataran River with<br />

Crawfurd and Wallick to inspect the forests and<br />

logistics of its shipping. What they found<br />

surpassed all expectation. Even after power shifted<br />

to Rangoon, Moulmein remained a teak town,<br />

shipping by the 1910s 60,000 tons of teak a year,<br />

about one fifth of the country's total production.

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

William Darwood, the Diana's chief engineer,<br />

realising the possibilities, stayed on in Moulmein<br />

where he married the daughter of the ship owner<br />

Captain Snowball, who had also just settled there.<br />

Snowball was famous in all the Indian Ocean<br />

ports and it was significant that he chose to settle<br />

in Moulmein. In 1825 this was the place to be. An<br />

Englishman, Darwood had served in the Bengal<br />

Marine and lost a leg in the Diana's assault on<br />

Martaban in 1824 for which he had been awarded<br />

a pension. He set up as shipbuilder and between<br />

1833 and 1841 launched eleven vessels. Darwood<br />

was one of over twenty ship builders established<br />

in Moulmein by the 1840s. As wooden hulls gave<br />

way to steel ones by the 1850s, ship building<br />

declined in Moulmein and after the Second<br />

Anglo-Burmese War larger vessels were to be built<br />

on the Rangoon River at Dalla. The river banks<br />

still abound with boat builders constructing<br />

trawlers and river launches.<br />

Many of Moulmein merchants were Scots.<br />

TD Findlay came to Moulmein in 1840 by way of<br />

Penang where he was to be a partner in a family<br />

owned store. He passed on that opportunity<br />

preferring to set up shop in Moulmein, where on<br />

a visit he realised the potential and formed a<br />

partnership with James Todd. Todd Findlay & Co<br />

imported goods from Glasgow and sent back teak<br />

in the same ships. Everything was in the hands of<br />

a small interrelated group of Glasgow families: the<br />

factories that produced all necessities for life and<br />

trade in the tropics; the ships that transported the<br />

goods; the shops that sold the goods; the insurers<br />

who covered the risky sea voyages; the logging<br />

companies; and, the banks that financed it all.<br />

Findlay and his network encapsulated this model.<br />

Later, with the shift to Rangoon, Todd Findlay &<br />

Co would become the main investors in another<br />

great Scot's project: the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong><br />

Company.<br />

Moulmein was important for only thirty<br />

years, as after the Second Anglo-Burmese War<br />

Rangoon became the capital of all Lower Burma.<br />

Thereafter Moulmein became a somewhat<br />

sleepy provincial town, of economic rather than<br />

political importance. Most of the great Scots'<br />

commercial houses relocated to Rangoon,<br />

leaving branch offices in Moulmein. Gone too<br />

were the governor and the military garrison.<br />

Moulmein was regarded as a very pleasant and<br />

comfortable town and a place of retirement for<br />

Europeans who chose not to go 'home'. This was<br />

the Bournemouth of Burma with quiet shady<br />

streets, dak bungalows and huge gardens strung<br />

along the three roads of the British town.<br />

Climbing the Kyaik-tha-lun pagoda hill to<br />

stand where Kipling stood, mistaking the<br />

Salween for Irrawaddy and becoming besotted,<br />

you can see the original town laid out between<br />

the corniche and the small range of hills which<br />

the pagoda dominates. It originally consisted of<br />

three thoroughfares, the Strand, Main Road and<br />

Upper Road, running parallel to the river along<br />

which the merchant's godowns and counting<br />

houses sat looking out across the Strand at their<br />

ships at anchor. You can see now that the town<br />

has spread inland to the eastern side of the hills.<br />

Ranged along the town hills are diverse pagodas<br />

and monasteries, nearly all dating from colonial<br />

times and in a hotchpotch of colonial classical<br />

and Rococo Burmese styles. The largest and<br />

most splendid Hindu temple in Burma sits<br />

brilliantly amongst this architectural melee.<br />

Gazing across the town you will see that all<br />

religions are represented and I would hazard<br />

that, there are as many mosques as pagodas, for<br />

under the British this was very much an Indian<br />

town. Not to be outdone by mosque or pagoda,<br />

church towers and steeples soar skywards in a<br />

mix of Gothic and Romanesque. Just beneath on<br />

the west side you will see a huge prison radiating<br />

out from a main block like a fan. Moulmein Jail,<br />

once a model prison, memorialises the legacy of<br />

the British as much as the churches and<br />

godowns. For the British were to pacify a territory<br />

where dacoits terrorised villages and pirates<br />

prayed on coastal traders. (Looking through my<br />

zoom lens I could see a very active prison<br />

population playing football or chinlon, cheered<br />

on by the guards.) To the north the great Salween<br />

graciously curves its way on the journey to distant<br />

Tibetan peaks. Closer you will see the jagged<br />

Zwekabin range of hills, the most prominent of<br />

which was known as the Duke of York's nose,<br />

though which Duke of York remains a mystery.<br />

From the east the Salween is joined by the Ataran<br />

and Gyaing Rivers that brought rafted teak down<br />

from the great forests that abutted Siam. Three<br />

enormous rivers thus meet in the estuary<br />

between Moulmein and Martaban and it is no<br />

surprise that Moulmein was to become an<br />

important port and trading post.<br />

17

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

Moulmein was once home to a young colonial policeman<br />

called Eric Blair, who later adopted the pseudonym George<br />

Orwell. His essay 'The Shooting of an Elephant' was set in<br />

Moulmein and begins with the wonderful line: "In Moulmein,<br />

in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people —<br />

the only time in my life that I have been important enough for<br />

this to happen to me."<br />

Orwell had strong Moulmein connections as his mother's<br />

family, the Limouzins, were from here. A Frenchman, his<br />

great-grandfather was a shipbuilder from Bordeaux and<br />

founded Limouzin & Co in 1826. Orwell arrived exactly one<br />

hundered years later and in the previous year his grandmother<br />

had died in Moulmein. There is still a Limouzin Street in<br />

downtown Moulmein.<br />

In 'The Shooting of the Elephant', Orwell shows an early<br />

disillusionment with the colonial system of which he, as the<br />

town's police superintendent, was a pillar. He describes how<br />

he was pressured by a crowd into shooting an elephant in musk<br />

even though it had ceased rampaging and was no longer a<br />

danger. Somehow the prestige of the British required him to<br />

act in an unnecessary and cruel way causing immense<br />

suffering to the beast as it died a long slow death. The shooting<br />

was a symbol of colonial rule. In Burmese Days, which is set<br />

up on the river in Katha, Orwell went on to ridicule the tedium<br />

of provincial colonial life. His record of life in Burma was<br />

deeply cynical, somewhat at variance with nearly all other<br />

contemporary accounts from this time.<br />

The fact that the poor elephant was a Moulmein elephant<br />

is relevant, for Moulmein was 'elephant city'. Teak rafts were<br />

floated down the three rivers to be gathered at their mouths<br />

and brought ashore by elephants, the logs were transported by<br />

elephants, even stacked in neat piles by elephants. Working<br />

elephants were everywhere in Moulmein and a feature of daily<br />

life. I wish there were statistics on this but there must have<br />

been several thousands stabled here. Elephants have identical<br />

life spans to humans, so most beasts were good for forty years<br />

of service. They were thus very valuable items. I once met a<br />

member of the Wallace family of Bombay Burmah Trading<br />

Corporation who returned to Burma in the nineties and<br />

encountered elephants branded BBTC before the war still<br />

working away.<br />

I first visited Moulmein in 1986. I was going to visit<br />

Professor Hla Pe who had been emeritus professor of Burmese<br />

at London University, before my time there, and had retired to<br />

Moulmein. I had heard many stories of Saya Hla Pe's charm,<br />

wit and eloquence and had longed to meet him. Back then<br />

under the Ne Win dictatorship foreigners were only allowed to<br />

travel to the usual tourist spots and I had to get special<br />

permission to go down to Moulmein. As the roads were so bad<br />

the train was the best way to get there. The terminus was at<br />

Martaban from where a ferry took me across the mile-wide<br />

Salween to Moulmein.<br />

As I crossed from the railway platform to the jetty I was<br />

confronted by a beaming police officer, "you are going to visit<br />

Saya U Hla Pe", it was a statement rather than a question, for<br />

the only foreigners ever to arrive in Moulmein were Saya's<br />

guests. The police were very kind and insisted on taking me<br />

across the river in a police launch and on the other side a police<br />

jeep was waiting to take me to Saya's mansion.<br />

This was the first of several visits to Saya over the years and<br />

the professor was one of the most erudite man in Burma and<br />

a fount of information on Burmese literature, language and<br />

culture. After a dram or two, he would hint that life in a<br />

provincial town, the Burmese Bournemouth, could at times be<br />

18

DISCOVER MORE VISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

ABOVE Adoniram<br />

Judson 1846<br />

LEFT Bamboo<br />

Buddha<br />

RIGHT<br />

St Matthews<br />

Church Moulmein<br />

dullish and thus he was all the more delighted to receive guests. His<br />

wife was from Moulmein and had insisted that they live there after<br />

his retirement from London University. Back then an index-linked<br />

UK pension went quite a long way in Burma and Saya lived in fine<br />

style and was something of a local celebrity receiving the obeisance<br />

of the town's great and good. On one occasion, not long married to<br />

Roser, we were sitting having dinner and the lights went out. Saya<br />

rushed to the phone and I heard him berate the manager of the local<br />

power station "didn't you hear that I have VIP foreign visitors staying".<br />

Saya is no longer with us, and Moulmein, as with so many<br />

Burmese towns, has seen some change. When we returned in the<br />

early 90s, after the SLORC putsch and a scramble to develop the<br />

country that collapsed into sanctions and the clasp of the Chinese, the<br />

old wooden godowns and counting houses were being demolished<br />

along the Strand in favour of the most architecturally miserable<br />

apartment blocks imaginable. Yet there are still many architectural<br />

gems to be found in the residential areas.<br />

It is best to start with the churches. My favourite is St Mathews,<br />

which is C of E, and so quintessentially English that for a moment<br />

you might think you have been transported back to the Home<br />

Counties. Consecrated in 1890 by Bishop John Miller Strachan (my<br />

adopted ancestor!) who was the first bishop of Rangoon, it was<br />

designed by the fashionable London firm of St Aubin and Wadling,<br />

and said to be identical to the English church in Dresden. The<br />

construction was funded by a single donor AW Kenny of whom I wish<br />

we knew more. The tower was added by the Bombay Burmah Trading<br />

Corporation, in memory of their young men who lost their lives in<br />

the Frist World War. Nearly all the memorials that would have covered<br />

the walls were desecrated by the occupying Japanese forces in the<br />

Second World War, except for one plaque remembering those of<br />

Moulmein who fell in the First World War. Burma buffs will recognise<br />

one or two old Burma names there including two Foucar boys, their<br />

family firm of Foucar & Company being a leading timber merchant.<br />

Moulmein and its colonial families go back further than anywhere<br />

else in Burma except perhaps Akyab in the Arakan. People like the<br />

Foucars stayed on and on, they may have sent their children back to<br />

be educated in England at absurdly early ages, but those kids came<br />

back, generation upon generation. ECV Foucar, a Rangoon lawyer and<br />

the fourth generation of his family in Burma, was author of I lived in<br />

Burma which is one of the best anecdotal descriptions of colonial life<br />

between the 20s and 40s – far more real in my opinion than Orwell's<br />

diatribes.<br />

St Mathews dedication stone remains outside and you will see<br />

that the stone was laid by Sir Charles Crosthwaite, Chief<br />

Commissioner for Burma and author of The Pacification of Burma, a<br />

classic work on insurgency that the Americans ought to have read<br />

before heading into Afghanistan. The choir stalls and ceiling bosses<br />

are said to be made from English oak and if you climb the belfry you<br />

will see the bell, cast in the foundry at Madras. There was a complex<br />

clock mechanism, with four clock panels working of one mechanism.<br />

It was explained that the one man in Moulmein who knew how it<br />

worked, and could repair it, had died and alas the clock died with him.<br />

The church had been used by the Japanese to store salt during the<br />

war and the salt has caused erosion into the brick work. One Pandaw<br />

passenger in the 90s was kind enough to donate a considerable sum<br />

towards the churches restoration. Some pointing work has been done<br />

but there is still much to do. When I was last there the priest showed<br />

me a collection of Christian headstones he had rescued when SLORC<br />

appropriated the Christian cemetery for redevelopment. I did not see<br />

them this time and wonder what happened to them?<br />

The Roman Catholic Cathedral, with its broad nave and lack of<br />

aisles, is more French in feel and was reroofed following war damage.<br />

The presbytery adjacent is a fine brick colonial house and typical of<br />

nearly all the colonial residences of Moulmein, with its shaded loggias<br />

running around and crisscross leaded fenestration. I love the<br />

anchored crosses found on the doors, something I have only seen on<br />

the churches of Burma emphasising a strong nautical element within<br />

colonial Christianity. An elderly nun showed us the tombs of French<br />

priests, set within the north transept including Pere Chirac, MEP<br />

(Mission Etrangers de Paris).<br />

Across the road is the American Baptist Church. This was the first<br />

church in Moulmein and its first incumbent was the Adoniram<br />

Judson (1788-1850) of Middlesex, Massachusetts, who had been in<br />

Burma since 1813. An indefatigable character, he travelled throughout<br />

Burma with personal bibles in English, Latin and Hebrew. Judson was<br />

the first person to translate the entire scriptures into Burmese. Still to<br />

this day his bible is used in most Burmese Christian churches, whatever<br />

their denomination. He is the King James of Burma. Judson also<br />

produced the first Burmese-English dictionary, a well-thumbed copy of<br />

which sits on my desk as I write. His success amongst the Burmese was<br />

19

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

minimal, but amongst the animistic Karen in the<br />

jungles of Tenasserim, just up river from<br />

Moulmein, Judson was viewed as a messianic<br />

figure. His legacy is huge: not just in Burma,<br />

where there are Judson Memorial churches<br />

everywhere, but right across in America there are<br />

Judson colleges, universities and libraries; there<br />

is even a town called Judsonia in Arkansas. In fact,<br />

far away in torpid Moulmein Judson theologically<br />

defined the American Baptist Church, some<br />

would say invented it, and his legacy lives on not<br />

just in Karen villages but in the counties of Texas.<br />

Of the religious edifices in Moulmein,<br />

whether cathedral, masjid or joss house, my<br />

favourite remains the Buddhist monastery of Sein<br />

Don Mipaya, situated on the town hills just to the<br />

south of the Kyaik-tha-lun pagoda and connected<br />

to its south stairway. Sein Don had been one of<br />

King Mindon's queens who fled to British<br />

territory following the palace coup of Thibaw in<br />

1859 and the subsequent cull of rival<br />

claimants. Given a house and pension,<br />

she lived with her court in some style in<br />

a Moulmein suburban house and<br />

decided, as her act of merit, to build this<br />

most sumptuous of monasteries. Despite<br />

its appalling condition, it remains one of<br />

the finest in Burma. The queen<br />

summonsed artists and craftsmen from<br />

across Burma to work and you can see<br />

they were the crème de la crème when it<br />

came to wood carving. The bracket<br />

figures supporting the column capitals<br />

are dynamically carved and full of vigour.<br />

The figures carved on the doors are full<br />

of wit and humour. When I last visited in<br />

the early 90s, the monk showed me the<br />

gaps where figures had been stolen in a<br />

nocturnal break in. At that time, when<br />

Burma was so poor, there was much<br />

thieving from religious sanctuaries, the<br />

loot going onto the international art<br />

market. Today Moulmein is a rich town<br />

once again and you can see that wealth<br />

being showered in ambitious new<br />

shrines throughout Mon State, it is a<br />

shame some of that money does not go into<br />

restoration.<br />

It is well worth pottering around the<br />

monasteries dotted along the town hills. There are<br />

several fine examples of colonial Burmese<br />

religious buildings and do not miss the<br />

monumental bamboo image. You can see that it<br />

was not just the dour scottish merchants who<br />

prospered during these times. These splendid<br />

monasteries, prayer halls and shrines are the work<br />

of merit of a very prosperous Buddhist<br />

community, whether Mon or Burmese.<br />

Along the Strand, despite the depredations of<br />

SLORC military planners in the 90s, there is still<br />

a good feel. There is a lively night bazaar where<br />

you can gorge yourself on barbequed sea food and<br />

a couple of very good restaurants. Moulmein<br />

today is the cleanest city in modern Myanmar and<br />

I was amazed to see plastic recycling stations. It<br />

would seem the Mon are far more house proud<br />

than their neighbouring Bama. There is a good<br />

museum of Mon culture that is worth a visit too.<br />

It is great to see the Mon going around in their<br />

traditional costumes with very jolly coloured<br />

checked taipon jackets. Moulmein is visibly<br />

prosperous today, same as it was two hundred<br />

years ago, as it sits astride the three rivers and<br />

commands all trade and the sea. The estuarial port<br />

is too shallow for modern shipping, but today the<br />

connections go the other way with the Pan Asian<br />

Highway passing through and connecting<br />

Moulmein to Thailand and beyond.<br />

Over the river to the west of Moulmein is Bilu<br />

Kyun or Devil Island which is now connected by<br />

a bridge. Guide books will tell you of artisanal<br />

villages: there is one that specialises in making<br />

slate tablets for schools and another for smoker's<br />

pipes. We visited the pipe village and bought quite<br />

a nice pipe for Roser's brother. The shop keeper<br />

explained that before trade for pipes had been<br />

good but nowadays few people smoke, so the<br />

wood carvers had branched out into other heavily<br />

carved products, more suited to the local market.<br />

I am not sure I will be hurrying back to Bilu Kyun.<br />

An essential excursion out of Moulmein is to<br />

Than-byu-zayat, about one hour south of<br />

Moulmein. Situated close the 'Death Railway'<br />

built by the Japanese in the Second World War,<br />

where they brutally expended prisoner of war<br />

labour, not to mention local slave labour. Here the<br />

Commonwealth War Graves Commission<br />

maintains the war cemetery as immaculately as if<br />

it were in the English counties. A visit is deeply<br />

moving and it would be a hard-hearted sort of<br />

person not to feel the tug of tears coming on. Look<br />

at their ages: many the same as my own son at 21.<br />

Alongside British servicemen are laid to rest<br />

young Australians, Dutchmen, Gurkhas and<br />

Indian. The Muslims point to Mecca and<br />

Christians to the East. Their sacrifice was huge<br />

and their name really does live forever more.<br />

We went down to Amherst Point, now called<br />

Kyaik-ka-me, partly in the hope of finding some<br />

good beaches and party to look at possible<br />

mooring positions and road access points for the<br />

Andaman Explorer when she moors here next<br />

year as part of her Burma Coastal Voyage. There<br />

were no nice beaches (they are further south) and<br />

the pagoda complex on the point tacky and of little<br />

interest. Along the way, you will see endless<br />

rubber plantations and judging by the number of<br />

trucks we saw bearing mats of raw rubber, the<br />

industry must be booming. More fun is a stop at<br />

the Wan-sein-toya complex on the road back from<br />

Than-byu-zayat. Here you will find the largest<br />

reclining Buddha in the world that the fit can<br />

climb up through a system of internal staircases.<br />

This was the work of the late Wan-sein-toya<br />

Sayadaw whose tomb you can visit close to the car<br />

park. He is enshrined within a very symbolic<br />

gilded sampan. I just wish he had channelled<br />

some of those generous donations into restoring<br />

some of Moulmein's Buddhist heritage.<br />

From Moulmein you can travel easily to Hpa-<br />

An, capital of Karen State, by car in a couple of<br />

hours but better a day trip by boat up the Salween.<br />

The Salween is very lovely with the<br />

Zwekabin mountain range running<br />

alongside and at times you would think<br />

you were in Guelin in China, so<br />

wonderfully mystical is the karst<br />

landscape around. Hpa-An is now another<br />

lively, prosperous Burmese city and a<br />

centre of education with several<br />

universities and colleges. The Karens here<br />

are predominantly Buddhist, having not<br />

succumbed to Judson's appeal. Worth a<br />

stop is the Mahar-sadan cave. You can<br />

walk through several great Buddha-filled<br />

caverns (carry your shoes as you will need<br />

them later) and you pop out of the other<br />

side to be rowed back round the mountain<br />

across a lake, through further grottos and<br />

then along a mini canal which the<br />

industrious Karen had dug out all in the<br />

name of local tourism, which they seem<br />

to benefit from.<br />

Moulmein was only for twenty-seven<br />

years under the British when it was of<br />

political importance, but its legacy<br />

remains strong, whether with its literary<br />

connections or architectural remnants. It<br />

is now the heart of a resurgent Mon regionalism,<br />

where after fifty years of Myanmar suppression<br />

the Mons can emerge again proud of their<br />

identity, language and culture. The Mons were the<br />

first of the South-East Asian peoples to be<br />

enriched by Buddhism producing moving<br />

sculpture and an enduring interpretation of<br />

Buddhist texts. It was thanks to the Mon-Khmer<br />

that we have the temples of Angkor Wat; and in<br />

11th century Pagan the captions on the mural<br />

paintings are in Mon, not Burmese. It was<br />

through the Mon that Buddhist literature, art and<br />

iconography disseminated through the region.<br />

The town at the confluence of the three rivers may<br />

not be very ancient, or may not have been<br />

important for very long, but it represents today a<br />

long, rich and deep culture. π<br />

ABOVE Thanbyuzayat<br />

war cemetery<br />

20

A special opportunity to share an educational family adventure during school<br />

holidays. Explore Asia in the comfort of a Pandaw vessel including daily excursions,<br />

cultural performances, movie nights and free mountain bikes to explore rural<br />

villages, temples and countryside.<br />

W W W . P A N D A W . C O M

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

NAGA STORY<br />

It suddenly dawned on me, after spending a couple of days<br />

cruising up the Chindwin River through the heart of<br />

Burma, that we hadn’t seen a single westerner. Even when<br />

our group docked up on the muddy banks to visit tiny local<br />

communities, we were the only outsiders to be seen.<br />

Pandaw’s very intriguing-sounding Voyage to Nagaland<br />

promises a real taste of adventure - and it certainly<br />

delivers. From the get go, I felt as though I was well off<br />

the beaten track with wavering Wi-Fi signal and the<br />

chugging of the boat engine being the only mechanical<br />

noise sounding among the birdsong or rain showers.<br />

My journey through one of Burma’s most remote regions<br />

started in the bustling city of Yangon. The throbbing<br />

metropolis, which was formerly the capital and known as<br />

Rangoon, is home to some of the worst traffic along with a<br />

spread of the world’s most revered temples, including the<br />

shimmering gold and diamond-encrusted 2,500-year-old<br />

Shwedagon Pagoda.<br />

On the first day of our Pandaw expedition, we met with<br />

our trip leader Ronald at the enormous 484-room Sule<br />