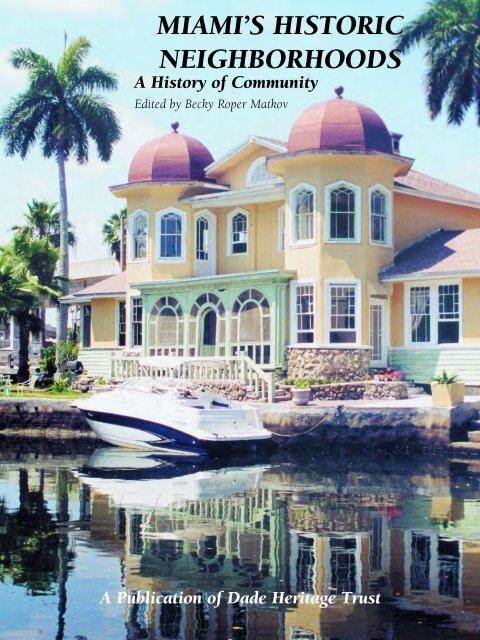

Miami's Historic Neighborhoods

An illustrated history of the city of Miami, Florida, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

An illustrated history of the city of Miami, Florida, paired with the histories of companies, families and organizations that make the region great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MIAMI’S HISTORIC<br />

NEIGHBORHOODS<br />

A History of Community<br />

Edited by Becky Roper Matkov<br />

A Publication of Dade Heritage Trust

Thank you for your interest in this HPNbooks publication. For more information about other<br />

HPNbooks publications, or information about producing your own book with us, please visit www.hpnbooks.com.

MIAMI’S HISTORIC<br />

NEIGHBORHOODS<br />

A History of Community<br />

Edited by Becky Roper Matkov<br />

A Publication of Dade Heritage Trust<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

A division of Lammert Publications, Inc.<br />

San Antonio, Texas

First Edition<br />

Copyright © 2001 <strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing<br />

from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to <strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network, 8491 Leslie Road, San Antonio, Texas, 78254. Phone (210) 688-9008.<br />

ISBN: 1-893619-15-X<br />

Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 2001087257<br />

Miami’s <strong>Historic</strong> <strong>Neighborhoods</strong>: A History of Community<br />

editor: Becky Roper Matkov<br />

contributing writers for<br />

sharing the heritage: Susan Cumins<br />

Paul Gereffi<br />

<strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network<br />

president: Ron Lammert<br />

vice president & project coordinator: Barry Black<br />

project representatives: E. “Tito” Berrios, Timothy Hemsoth, Bari Nessel,<br />

Flora Tartaglia, Ted del Valle, Jessica Vlasseman<br />

director of operations: Charles A. Newton, III<br />

administration: Angela Lake<br />

Donna Mata<br />

Dee Steidle<br />

graphic production: Colin Hart<br />

John Barr<br />

PRINTED IN SINGAPORE<br />

2 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

CONTENTS<br />

4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

5 FOREWORD<br />

by Governor Jeb Bush<br />

6 A SENSE OF COMMUNITY<br />

by Becky Roper Matkov<br />

10 HISTORY IS WHERE YOU FIND IT<br />

by Arva Moore Parks<br />

15 VOICES FROM THE PAST<br />

by Helen Muir<br />

18 MIAMI<br />

by Aristides Millas<br />

26 THE MIAMI RIVER<br />

by Robert S. Carr<br />

30 SPRING GARDEN<br />

by James Broton<br />

32 OVERTOWN<br />

by Dorothy Jenkins Fields<br />

35 MIAMI CITY CEMETERY<br />

by Penny Lambeth<br />

38 MORNINGSIDE AND BAY POINT<br />

by Gail Meadows and William E. Hopper, Jr.<br />

41 MIAMI BEACH<br />

by Howard Kleinberg<br />

48 MIAMI SHORES AND EL PORTAL<br />

by Seth Bramson<br />

50 NORTHEAST DADE: BISCAYNE PARK,<br />

FULFORD, NORTH MIAMI BEACH<br />

AND AVENTURA<br />

by Malinda Cleary<br />

57 OPA-LOCKA: A VISION OF ARABY<br />

by Thorn Grafton<br />

60 MIAMI LAKES AND THE DAIRIES<br />

THAT MADE DADE<br />

by Donald Slesnick<br />

63 HIALEAH<br />

by Horatio L. Villa<br />

66 MIAMI SPRINGS: GLEN CURTISS’ DREAM<br />

by Mary Ann Goodlett-Taylor<br />

70 NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE<br />

by Stephen Tiger<br />

72 BROWNSVILLE<br />

by Enid C. Pinkney<br />

76 RIVERSIDE AND SHENANDOAH<br />

by Paul S. George<br />

81 LITTLE HAVANA AND CALLE OCHO<br />

by Leslie Pantin, Jr.<br />

83 CLIFF HAMMOCK<br />

by Julia Hodapp Cohen<br />

87 COCONUT GROVE<br />

by David Burnett<br />

94 KEY BISCAYNE<br />

by Joan Gill Blank<br />

100 CORAL GABLES<br />

by Ellen Uguccioni<br />

106 CENTRAL MIAMI:<br />

“THE LOST PART OF CORAL GABLES”<br />

by Samuel D. LaRoue, Jr.<br />

109 SOUTH MIAMI<br />

by Susan Perry Reading<br />

114 PINECREST<br />

by Georgia Tasker<br />

118 KENDALL<br />

by Paul S. George<br />

123 OLD CUTLER AND THE DEERING ESTATE<br />

by Christopher R. Eck<br />

129 SOUTH DADE:<br />

HOMESTEAD, FLORIDA CITY, AND REDLAND<br />

by Robert J. Jensen and Larry Wiggins<br />

136 SHARING THE HERITAGE<br />

206 INDEX<br />

208 SPONSORS<br />

CONTENTS ✧ 3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

With much appreciation, Dade Heritage Trust would like to thank<br />

the following for all their help:<br />

DEBORAH TACKETT, PHOTO EDITOR, for the vital role she played in helping locate,<br />

photograph and organize so many of the photos in this book.<br />

The CONTRIBUTING WRITERS, who gave so freely of their knowledge,<br />

historic resources, photographs, time and talent:<br />

Governor Jeb Bush<br />

Becky Roper Matkov<br />

Arva Moore Parks<br />

Helen Muir<br />

Aristides Millas<br />

Robert S. Carr<br />

James Broton<br />

Dorothy Jenkins Fields<br />

Penny Lambeth<br />

Gail Meadows and<br />

William Hopper<br />

Howard Kleinberg<br />

Seth Bramson<br />

Malinda Cleary<br />

Thorn Grafton<br />

Donald Slesnick, II<br />

Horatio Villa<br />

Mary Ann Taylor<br />

Stephen Tiger<br />

Enid Pinkney<br />

Paul George<br />

Leslie Pantin<br />

Julia Cohen<br />

David Burnett<br />

Joan Gill Blank<br />

Ellen Uguccioni<br />

Sam LaRoue<br />

Susan Redding<br />

Georgia Tasker<br />

Christopher Eck<br />

Robert Jensen and<br />

Larry Wiggins<br />

The PHOTOGRAPHERS whose donated work so enhanced this book:<br />

Deborah Tackett, Antoinette Naturale, Becky Roper Matkov, Lambeth & Nagle Communications, Elena Carpenter of the Brickell Post,<br />

Thorn Grafton, Dan Forer, Fernando Suco, Larry Wiggins, Julia Cohen, Randall Robinson, Malinda Cleary, William Hopper, Steven Brooke,<br />

John Gillan, Phil Brodatz, Michael Conway, Nesie Summers, Rudi Klein, Paulette Mortimer, Jack Goodier, Norman McGrath, Mark Greene,<br />

Charlie Williams, Mel Rea McGuire, Jose Gelabert-Navia<br />

ARCHIVAL AND PHOTOGRAPHIC RESOURCES:<br />

The Florida State Archives; The <strong>Historic</strong>al Association of Southern Florida; Dade Heritage Trust Archives; The Black Archives History and<br />

Research Foundation of South Florida; North Miami <strong>Historic</strong>al Society; The Collection of Arva Moore Parks; The Collection of Seth Bramson; The<br />

Collection of Sam LaRoue; The Collection of Joan Gill Blank; The Collection of Christopher Eck; The Collection of Bob Carr; The Collection of<br />

Carolyn Junkin; The Collection of the John Witty Family; The Collection of Helen Muir; William Jennings Bryan Library Archives; Overtown<br />

Main Street; Temple Israel; Miami-Dade <strong>Historic</strong> Preservation Division; Miami-Dade Park and Recreation Department; Miami-Dade Community<br />

College; Vizcaya Museum and Gardens; The Kampong; Fairchild Tropical Garden; Coconut Grove Arts Festival; Miami Downtown Development<br />

Authority; Metro-Dade Transit; Miami-Springs <strong>Historic</strong>al Museum; Miami-Dade Public Library System Romer Collection; Parrot Jungle and<br />

Gardens; Homestead Miami Speedway; Kiwanis Club of Little Havana; National Park Service; Biscayne National Park; Bill Baggs Cape Florida<br />

State Recreation Area; Arquitectonica; The Graham Companies; DEEDCO; Aventura Mall; Bal Harbour Shops; The Biltmore Hotel; R.J.<br />

Heisenbottle Architects, P.A.<br />

Ceci Williams, for handcoloring the photograph of the Ideal Model Home.<br />

Thomas J. Matkov, for his legal assistance.<br />

The Greater Miami Convention and Visitors Bureau, for the use of their map.<br />

The Board Members of Dade Heritage Trust, for all their support.<br />

Dade Heritage Trust Staff Members Luis Gonzalez and Katie Halloran.<br />

The staff of the <strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network, for all their assistance.<br />

The companies and individuals who purchased Profiles, especially those with J. Poole Associates, Inc., Realtors,<br />

who were the first to buy a profile—and have been so patient in waiting for this book.<br />

4 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

FOREWORD ✧ 5

6 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS<br />

(COURTESY OF MIAMI DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE)

After Hurricane Andrew, friends and neighbors worked together to clear roads and yards filled with limbs and debris. (PHOTOS BY BECKY ROPER MATKOV)<br />

A SENSE OF COMMUNITY<br />

B Y B ECKY R OPER M ATKOV<br />

In 1978, when we first moved to Miami<br />

from Richmond,Virginia, I enrolled our son in<br />

first grade, filled up our suburban look-alike<br />

kitchen with groceries, and set about to dis -<br />

cover the “heart” of our new community. That<br />

had been an easy task in Richmond, when<br />

your next door neighbor—who had lived in<br />

his old colonial for forty years—brought you<br />

roses and told you about the history of each<br />

house on the street and who was the best<br />

plumber to fix your leaky faucets and how the<br />

pharmacy three blocks away would deliver<br />

prescriptions and which were the proper<br />

clubs and churches to belong to and oh, yes,<br />

he would introduce you to “everyone.”<br />

It had not been an easy task in Northern<br />

Virginia, where I had been raised in the<br />

“metropolitan Washington area” of McLean.<br />

The rambling old farmhouses in the center<br />

of McLean had been torn down by the<br />

1960s, replaced first by gas stations, then by<br />

strip malls and chain restaurants, and then<br />

by office parks and mega-malls that gobbled<br />

up miles of rolling countryside. One subdivision<br />

blended into another, all united by<br />

endless traffic congestion.<br />

What I found in Miami at first glance<br />

seemed dismayingly similar. Old mansions<br />

along Brickell Avenue were being bulldozed<br />

daily for highrise office buildings. Expressways<br />

and I-95 were always under construction,<br />

making little improvement in traffic flow even<br />

when completed. Dade County seemed to<br />

spread out forever, with no defined bound -<br />

aries, no center, no history, no essence. There<br />

appeared to be “no ‘there’ there.”<br />

However, I soon learned that that was not<br />

the case. Vizcaya and the Barnacle showed<br />

me another world and time that once existed<br />

here. The Junior League’s Designer Show<br />

House in the French Village and a tour of the<br />

long-closed Biltmore introduced me to the<br />

charms of old Coral Gables. Photographing<br />

Downtown Miami for an architectural guidebook<br />

and writing a story on the Miami River<br />

intrigued me with the rejuvenation potential<br />

for the city’s tired central core. Then along<br />

came Dade Heritage Trust! Social events at<br />

beautiful old homes and landmarks, restoration<br />

projects, eye-opening conferences and<br />

seminars, and a chance to create and publish<br />

a magazine on historic preservation followed.<br />

And along the way, I learned something<br />

about Miami, this complex, diverse, multifaceted,<br />

far-flung, fast-changing, never-dull<br />

metropolis: Miami is not one place, but<br />

many. Not one story, but hundreds, thou -<br />

sands of stories.<br />

Professor Aristides Millas, in his chapter<br />

on the City of Miami, quotes Dr. William<br />

Davenport, who wrote in 1909, “Miami was<br />

a collection of strangers…. We had all come<br />

from someplace else.” In many ways, that<br />

has not changed. “Natives” are being born<br />

here every day, of course, but we have<br />

numerically many more people coming from<br />

afar, whether it’s Atlanta or Havana, New<br />

York or Rio, Washington or Kiev,<br />

Minneapolis or Port au Prince.<br />

Too few have shared their stories with<br />

others, and too few have listened to the stories<br />

of others. Residents of Miami Beach may<br />

seldom visit Homestead. People who live in<br />

Aventura may never go to Hialeah. Opa-locka<br />

and Key Biscayne may seem worlds apart.<br />

Newcomers from less unwieldly parts of the<br />

planet often remark that Miami is a confusing<br />

city to really get to know. It is a challenge to<br />

embrace all this geographic and demographic<br />

expanse as one’s own hometown.<br />

The role of historic preservation is to save<br />

physical remnants of our past so that people can<br />

understand that they are part of a continuum of<br />

civilization, a part of the ongoing story of where<br />

CHAPTER I ✧ 7

Matheson Hammock Marina was decimated by Hurricane Andrew on August 24, 1992.<br />

they are living. People lived along the Miami<br />

River and Biscayne Bay thousands of years before<br />

the first condo was ever built on Brickell Avenue.<br />

History books tell you that. The Miami Circle<br />

archeological site, saved by preservationists from<br />

being bulldozed into oblivion, can show you<br />

that. Hardy pioneers survived on Key Biscayne<br />

since 1825, long before the Rickenbacker<br />

Causeway made possible Mackle homes and the<br />

latest bumper crop of multi-million dollar man -<br />

sions. History books tell you that. The Cape<br />

Florida Lighthouse, restored by preservationists,<br />

shows you that.<br />

Walking into an historic building, or<br />

through an historic neighborhood, is a<br />

three-dimensional experience. No book, no<br />

photograph, no museum exhibit, can convey<br />

that experience as well as the reality of physically<br />

being there with the real thing.<br />

<strong>Historic</strong> preservation seeks to preserve<br />

the character of an older neighborhood and<br />

to make buildings past their prime once<br />

more appreciated and nurtured. <strong>Historic</strong><br />

preservation recycles structures and sites,<br />

restoring their youth, refreshening them for<br />

new lives and times.<br />

Preserving physical reminders of our<br />

communal past increases a sense of community<br />

for our city as a whole. It is a way of<br />

welcoming us, of informing us, of inviting us<br />

to be a part of this place called Miami,<br />

whether our grandparents lived here or we<br />

just arrived last week.<br />

Developing a sense of community is not<br />

an easy task. Festivals and celebrations like<br />

Dade Heritage Days and Calle Ocho and Art<br />

Deco Weekend expose thousands to differ -<br />

8 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS<br />

ent cultures and neighborhoods. A common<br />

history, as experienced by Cuban exiles or<br />

Holocaust survivors, binds people together.<br />

Civic associations and historic districts give<br />

residents of a neighborhood a forum and<br />

structure to develop ties with one another,<br />

whether for holiday parties, house tours,<br />

park preservation or political lobbying.<br />

A well-executed vision by the developers<br />

of a city, as seen in Coral Gables, Miami<br />

Springs, and Miami Shores, goes a long way<br />

in creating a sense of place. Incorporation<br />

into a separate municipality, as in Pinecrest<br />

and Key Biscayne, has given residents a sense<br />

of pride and participation missing before<br />

they had a clearly delineated community.<br />

And sometimes, calamities or perils that<br />

befall an area unite people who have been<br />

living as strangers in suburbia and transform<br />

them into a close-knit community of friends.<br />

That is what happened to neighborhoods<br />

all over Miami when Hurricane Andrew<br />

struck on August 24, 1992. For everyone in<br />

the county there was a break in the flow of<br />

life as as usual. For those closest to the eye of<br />

this storm—described by TV weatherman<br />

Brian Norcross as “the strongest hurricane to<br />

ever hit a major metropolitan area”—there<br />

was destruction beyond belief. The storm<br />

slashed everything from Key Biscayne south<br />

through Gables by the Sea, Pinecrest,<br />

Kendall, the Deering Estate, Cutler Ridge,<br />

Cauley Square, the Redland, Homestead and<br />

Florida City. The terrain looked like a nuclear<br />

bomb had leveled what had been the greenest<br />

and lushest part of Dade County. Trees<br />

were stripped of their leaves, their branches<br />

gnarled and twisted. Roofs were ripped off,<br />

windows and doors blasted out, mailboxes<br />

and lights smashed. Refrigerators were floating<br />

in flooded garages. Pools were filled with<br />

sludge and dead animals. Boats were blown<br />

from marina docks into mangrove swamps.<br />

Tall concrete utility poles were snapped like<br />

toothpicks. School gyms—and entire shopping<br />

centers—were devastated.<br />

Our neighborhood had no phones, no<br />

water, no security and no electricity for<br />

weeks. Air conditioning in the 90 degree<br />

heat was a luxury one could only dream<br />

about. Ice was a priceless commodity. Chain<br />

saws and generators were avidly sought<br />

after, as was plastic sheeting to cover up<br />

leaky roofs in the torrential downpours. The<br />

streets were lined with mountains of trash.<br />

The roof and second floor of this home blew away while a family of five huddled downstairs under a mattress.

Troops from the 82nd Airborne camped on<br />

the grounds of my daughter’s school.<br />

Helicopters droned overhead incessantly,<br />

evoking memories of the Vietnam War.<br />

But out of this destruction and disruption<br />

came something to treasure. As we emerged,<br />

dazed, from our houses after the storm had<br />

passed, we all met in the street. One family’s<br />

entire second floor had blown away, and the<br />

next door neighbors had rushed over to rescue<br />

them during the storm. People who barely<br />

knew each other were offering to share their<br />

homes, food and gasoline and were pitching<br />

in to clear each other’s yards. Fences had been<br />

blown down, literally and figuratively, and<br />

neighbors were talking to each other who had<br />

never even met before. On countless streets<br />

with broken traffic lights, drivers were unusually<br />

polite to each other, resulting in traffic<br />

flowing with amazing smoothness.<br />

Never had we seen such total blackness at<br />

night, without even a faint glow from distant<br />

city lights. So we fell into an old fashioned<br />

rhythm of rising with the sun and doing physical<br />

labor—lots of it!—early on to avoid the<br />

horrendous heat of the day. We talked with<br />

friends on the porch—the inside of the house<br />

was too hot!—and pooled our resources for<br />

communal cookouts with neighbors in the<br />

early evening. We used our flashlights to find<br />

our way to bed when darkness descended,<br />

with no computers, no answering machines,<br />

no videos and no television to distract us.<br />

Through the sweat and aggravation and<br />

distress, we were forced to take time to get to<br />

know each other. We cried at our losses of<br />

antiques or art or special family photo -<br />

graphs, but we laughed a lot too.<br />

Friendships were made which have lasted<br />

through the decade. We have shared reconstruction<br />

horror stories, weddings, puppies,<br />

margaritas, key lime bread, roses, a tragic<br />

funeral, birthdays, Christmas parties, a book<br />

signing, a bat mitzvah, progressive dinners<br />

and “Hurricane Andrew” anniversaries.<br />

Not only on our street, but throughout<br />

many streets in Miami-Dade, Hurricane<br />

Andrew forged a communal camaraderie.<br />

<strong>Neighborhoods</strong> became communities that<br />

cared and shared.<br />

When people get to know each other,<br />

bridges are built that unite groups and individuals.<br />

It is our hope that this book on<br />

Miami’s <strong>Historic</strong> <strong>Neighborhoods</strong> will introduce<br />

you to your neighbors and “build<br />

bridges” between different communities.<br />

There are countless neighborhoods and stories<br />

in Miami, and we’ve only highlighted a<br />

few—but we hope that these will make us all<br />

feel less like strangers, and more like friends.<br />

Houses and landscaping in the eye of the storm looked as though they had been bombed in a war zone.<br />

With no school, no air conditioning, and no television for weeks, neighborhood kids played card games to while away hot afternoons.<br />

Neighbors—who had become friends—celebrate with a “lights on” party when electricity was restored after three weeks.<br />

Reconstructing damaged homes took months, even years, longer.<br />

CHAPTER I ✧ 9

In the 1920s, developments boomed all over Dade County, offering the “ideal home and neighborhood.” (FLORIDA STATE ARCHIVES PHOTO HAND-COLORED BY CECI WILLIAMS)<br />

HISTORY IS WHERE YOU FIND IT<br />

B Y A RVA M OORE P ARKS<br />

“No place is a place until things that have happened in it are remembered.”<br />

—Wallace Stegner<br />

Nothing reveals Miami’s history better than<br />

its own, distinctive historic places. They store<br />

memories and events and safeguard the lessons<br />

of the past. They hold precious pieces of human<br />

life and connect generation to generation.<br />

Until recently, Miamians have had little<br />

interest in preservation. Instead of saving the<br />

best, each generation has thoughtlessly bulldozed,<br />

modernized or otherwise destroyed<br />

much of what they found when they arrived.<br />

As a result, many important landmarks have<br />

disappeared and the monuments to Miami’s<br />

founding can only be seen in old photographs.<br />

But perceptive eyes can still discover frag -<br />

ments of early days, and preservationists have<br />

helped save some of what remains. In an<br />

attempt to right past wrongs, they have also<br />

focused on preserving the more recent past<br />

and securing its future.<br />

Without landmarks, we can lose our way.<br />

Before we can look ahead, we must first look<br />

around and see where we are and where we<br />

have been. Only by doing this can we can<br />

become what author Wendell Berry calls a<br />

“placed person.”<br />

Place, after all, is the root of our existence.<br />

It marks our beginning and our end. It gives us<br />

identity and shapes our character. It grounds<br />

our memories. Place is our where: where we<br />

came from, where we live, where we work,<br />

where we met, where we have been, where we<br />

are going. Place brings continuity to our life. It<br />

joins past to present, present to future, and us<br />

to each other.<br />

Just as place defines us, we define place and<br />

give it meaning. We are place’s who: who came,<br />

who left, who lived, who died, who built, who<br />

conquered, who ruled, who pillaged, who<br />

destroyed and who restored. We make,<br />

change, and write place’s history.<br />

The place we live in today is Greater Miami.<br />

Our past may be someplace else but our today<br />

is here. We are Miami’s now. But we are not<br />

alone. All the people who lived here in the past<br />

or will live here in the future line up with us forever.<br />

Our feet walk the same special piece of<br />

earth where, eight millennia before our calendar<br />

began, others trod. Recent discoveries of the<br />

Miami Circle and the Deering Fossil Site have<br />

re-written what we thought we knew about the<br />

earliest people to call Miami home. As humans<br />

of the twenty-first century, our connection with<br />

Miami begins not with our arrival but with these<br />

people and all the rest who will follow us in the<br />

next millennium.<br />

Just 2l years after Columbus discovered<br />

what the Europeans called the New World,<br />

Juan Ponce de León sailed into Biscayne Bay<br />

and called the area Chequescha (Tequesta)<br />

presumably after the native people he<br />

encountered. In 1567, just two years after<br />

founding St. Augustine, the oldest perma -<br />

nent European settlement in what is now the<br />

United States, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés<br />

built a short-lived mission on the north bank<br />

of the Miami River near its mouth. During<br />

the next two centuries, Spain’s other two<br />

attempted settlements in the Miami area were<br />

also short-lived, but the Spanish remained<br />

friendly with the native people. When the<br />

English took control of Florida in 1763, most<br />

of the Tequesta Indians left with the Spanish<br />

for Havana.<br />

During this ten-year British period, and<br />

after Florida was returned to Spain,<br />

Bahamians moved into the Miami area but left<br />

no trace of their Cape Florida settlement.<br />

Although no buildings remain from the earliest<br />

Spanish and Bahamian settlements, arti -<br />

facts uncovered in various archaeological digs,<br />

including the one on the north bank of the<br />

Miami River, prove that they were here. These<br />

precious remnants of the past can be seen at<br />

the <strong>Historic</strong>al Museum of Southern Florida.<br />

In 1825, four years after Florida became a<br />

United States territory, the government built the<br />

Cape Florida Lighthouse on Key Biscayne in an<br />

effort to stop the frequent wrecks on the Great<br />

Florida Reef. In 1836, the Seminoles destroyed<br />

the light during the second in a series of three<br />

costly wars. The Cape Florida Lighthouse, which<br />

was re-built in 1845, is Miami’s oldest complete<br />

structure. Because most of the keepers of the<br />

Cape Florida Lighthouse traced their roots to the<br />

Bahamas, the lighthouse is the earliest link to our<br />

first permanent European and African settlers.<br />

Soon after the government built the light -<br />

house, South Carolinian Richard Fitzpatrick<br />

bought four tracts of land on the north and south<br />

bank of the Miami River from two Bahamian<br />

families, the Egans and the Lewises. When<br />

Florida became a territory of the United States in<br />

10 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

1821, they had the distinction of being the only<br />

private landowners on the mainland. In 1838,<br />

two years after the 2nd Seminole War began, the<br />

U.S. opened Fort Dallas on Fitzpatrick’s property.<br />

At war’s end, Fitzpatrick sold his land to his<br />

nephew William F. English. English built a rock<br />

plantation house and a long building to serve as<br />

slave quarters on the north bank. In 1845,<br />

English also platted the Village of Miami just<br />

across the river. Unfortunately, the Seminoles<br />

forced English to flee before his dream for a new<br />

city could be realized. The U.S. Army returned<br />

and re-opened Fort Dallas. They completed the<br />

two rock buildings and used them as part of their<br />

military complex. As late as the 1890s, these two<br />

buildings were the only substantial structures on<br />

the north bank of the river.<br />

Following the Civil War, a visitor noted that<br />

the long building housed a motley crew of<br />

deserters and runaways. In the 1870s, it served<br />

as the Dade County Courthouse. In the early<br />

1900s it became a private residence and later a<br />

tea room. When the building was slated for<br />

demolition in 1925 to make way for the Robert<br />

Clay Hotel (now demolished), the Daughters<br />

of the American Revolution and the Miami<br />

Woman’s Club initiated Miami’s first preservation<br />

effort to save it. They raised the money to<br />

move what became known as Fort Dallas to<br />

Lummus Park, a city-owned park up river.<br />

Ft. Dallas still resides in Lummus Park along<br />

with Miami’s oldest house, the Wagner<br />

Homestead, built in 1858 by William Wagner, a<br />

sutler who remained in Miami when the last<br />

Seminole War was over. Dade Heritage Trust led<br />

the effort to move and reconstruct Wagner’s<br />

House in the park in 1979. Unfortunately, the old<br />

plantation house that also served as the home to<br />

Julia Tuttle, the “Mother of Miami,” was torn<br />

down in the 1920s without a whimper of protest.<br />

When Julia Tuttle arrived in 1891, what<br />

would become downtown Miami had changed<br />

very little since English’s time. William and<br />

Mary Brickell had a trading post on the south<br />

bank of the river and were doing a brisk busi -<br />

ness with the Indians. Brickell and his family<br />

had arrived two decades earlier and had pur -<br />

chased all of English’s land on the south side of<br />

the river extending to what would become<br />

Coconut Grove. Unfortunately, nothing remains<br />

of the Brickell trading post or their 1906 man -<br />

sion, torn down in 1963. Their greatest legacy is<br />

beautiful Brickell Avenue, platted by Mary<br />

Brickell in 1911. A monument to Mary Brickell<br />

in the median of Brickell Avenue between S.W.<br />

Sixth and Seventh Streets was dedicated by<br />

Dade Heritage Trust in 1998, thanks to the<br />

efforts of activist Carmen Petsoules.<br />

By 1891, Coconut Grove held the distinction<br />

of being the first real community in South<br />

The Mouth of the Miami River one hundred years ago, looking east toward Biscayne Bay from where the Brickell Bridge now<br />

spans the river. The 2000-year-old Miami Circle archeological site, discovered in 1998, is located behind the white building<br />

in the center of the photo. (COURTESY OF THE COLLECTION OF CHRISTOPHER ECK)<br />

Florida. It had a population of over fifty hearty<br />

souls, a six-year old hotel, a community Sunday<br />

school, the first school in what is now Dade<br />

County, a yacht club, a woman’s club and a general<br />

store. Ralph Munroe, who came from Staten<br />

Island, New York, had just completed his new<br />

home, called the Barnacle. Munroe also brought<br />

the first northern tourists into Miami to stay at<br />

Charles and Isabella Peacock’s Bay View Hotel,<br />

later the Peacock Inn. It stood on the ridge<br />

between two magnificent oaks in today’s Peacock<br />

Park. The inn spurred other development,<br />

including the founding of Kebo—Miami’s first<br />

black community—on today’s Charles Avenue.<br />

Although Coconut Grove has experienced<br />

enormous change in recent years, it still has the<br />

greatest concentration of historic sites linked to<br />

the romantic “Era of the Bay” before the railroad<br />

came to South Florida and closed the frontier.<br />

The 108-year-old Woman’s Club still sits on its<br />

corner of South Bayshore Drive and McFarlane<br />

Road in a 1921 building designed by renowned<br />

Miami architect Walter De Garmo. The 1882<br />

grave of Ralph Munroe’s first wife, Eva, is next to<br />

the Coconut Grove Library and is Miami’s oldest<br />

marked grave. The first Sunday school and<br />

schoolhouse [1887], which once stood behind<br />

the library, was moved to the grounds of<br />

Plymouth Congregational Church [1917]. The<br />

Biscayne Bay Yacht Club [1887] is located on the<br />

bayfront a short distance to the east in a 1932<br />

DeGarmo building. Charles Avenue, the first<br />

street in historic Kebo, still has some important<br />

historic sites including the E.W.F. Stirrup House<br />

[1897], the Mariah Brown House [c 1900] and<br />

the historic Bahamian-style cemetery, on the corner<br />

of Charles and Douglas Roads. The Barnacle,<br />

now a State of Florida historic site, sits just a<br />

short distance away off busy Main Highway. It<br />

still offers us a rare opportunity to re-enter this<br />

“Era of the Bay” and see what Coconut Grove<br />

offered its pioneers before there was a Miami.<br />

Lemon City, another pre-Miami community,<br />

grew up five miles north of the Miami River.<br />

Lemon City had the best dock in the area and by<br />

1892 was connected by a stage line to Lantana.<br />

Like Coconut Grove, Lemon City had a school, a<br />

church, a library and a growing population.<br />

Unfortunately, almost nothing remains from<br />

Lemon City except the Lemon City Drug Store<br />

and Post Office [1902] on the corner of N.E.<br />

Second Avenue and 6lst Street—now the heart of<br />

Little Haiti. One important link to old Lemon City<br />

stands proudly on NW Second Avenue and 62nd<br />

Street (formerly Avenue G and Pocomoonshine<br />

Road). Miami Edison Middle School traces its<br />

roots to the original Lemon City School and later<br />

Lemon City Agricultural High School. Significant<br />

portions of the 1928 former high school, gymnasium<br />

and auditorium have been painstakingly<br />

restored and joined to a beautiful new addition.<br />

The melding of the old with the new at Miami<br />

Edison Middle School, and the dialogue and connection<br />

of old timers with new comers that resulted,<br />

shines as a model for the future.<br />

South Florida’s other pre-railroad community<br />

grew up in far South Dade. In 1884,<br />

William Fuzzard opened the Cutler post office<br />

near what is now Coral Reef Drive (152nd<br />

Street). Fuzzard also chopped Old Cutler<br />

Road through the hammock to Coconut<br />

Grove. Remnants of the Cutler community<br />

and the original road are found on 168th<br />

Street and at the Charles Deering Estate. The<br />

site includes the historic Richmond Inn<br />

[1896] that was once a part of the town of<br />

CHAPTER II ✧ 11

Cutler. Carefully re-constructed after being<br />

almost totally destroyed by Hurricane Andrew,<br />

the Richmond Inn reminds us of the time<br />

when Cutler, like Coconut Grove and Lemon<br />

City, was a thriving pioneer settlement.<br />

As soon as Julia Tuttle arrived from<br />

Cleveland in 1891, she set about to transform<br />

a forgotten frontier into a new city. Like those<br />

who came before her, she knew that Miami<br />

would never develop until it became more<br />

accessible. Offering half her land to anyone<br />

who brought a railroad into Miami, Tuttle first<br />

sought the help of Henry Plant, who had<br />

extended his railroad as far south as Tampa.<br />

After a harrowing trip across the Everglades<br />

from Tampa to Miami, the Plant people<br />

quickly lost interest in Tuttle’s proposal. She<br />

then turned to Henry Flagler, whose railroad<br />

was steaming down the East Coast of Florida<br />

connecting his string of luxury hotels. Even<br />

though Flagler reached Palm Beach by 1894,<br />

he ignored Tuttle until the terrible freeze of<br />

1894-95 made him realize Miami’s potential<br />

as a winter fruit and vegetable center. The<br />

idea of bringing tourists in and vegetables out<br />

appealed to him. At Tuttle’s behest, Flagler<br />

finally came to see Miami. After a dinner at<br />

the Grove’s Peacock Inn and an offer of part of<br />

Brickell’s land to sweeten the pot, Flagler was<br />

ready to deal and the railroad was on its way!<br />

In April 1896, the first train chugged into<br />

Miami. A month later, Miami had its first<br />

newspaper, The Miami Metropolis, and by July<br />

had become an incorporated city with onethird<br />

of the incorporators African Americans.<br />

Five months later, much of the new “Magic<br />

City,” as it was called, burned to the ground in<br />

a disastrous Christmas night fire. Despite this<br />

setback, Flagler’s magnificent Royal Palm Hotel<br />

opened a month later at what is now the<br />

Dupont Plaza parking lot. Unfortunately, one<br />

of the only reminders of Miami’s founding<br />

years and Henry Flagler’s legacy is a simple<br />

house on the Miami River (Bijan’s Fort Dallas<br />

Restaurant & Raw Bar) that was moved just<br />

west of the Hyatt Hotel in 1979. Painted<br />

Flagler yellow, the distinctive color of all<br />

Flagler’s railroad stations and hotels, it was one<br />

of two blocks of Royal Palm Cottages that<br />

Flagler built for newcomers to his instant city.<br />

Flagler also donated the land on Flagler<br />

Street and SE Third Avenue for the First<br />

Presbyterian Church, dedicated in 1900. When<br />

it was torn down in the 1940s, the interior was<br />

reconstructed in the chapel of the new church<br />

on Brickell Avenue. Recently, one other frag -<br />

ment of Flagler’s Miami was discovered on the<br />

southwest corner of Flagler Street and SE/NE<br />

First Avenue. Although hidden behind a 1940s<br />

facade, Flagler’s 1897 brick Fort Dallas Building,<br />

home to his real estate division, still stands as a<br />

sort of “snail darter” link to Henry Flagler and<br />

the earliest days of the City of Miami.<br />

As the twentieth century began, Miami lost<br />

its frontier feeling. One- and two-story vernacular<br />

storefronts with arcaded sidewalks to protect<br />

the shopper from sun and rain gave downtown<br />

a tropical, small town atmosphere. A glimpse of<br />

this era can be seen at NE First Avenue and First<br />

Street. The old U.S. Post Office building, now<br />

Office Depot, and the buildings across the street<br />

including the Ralston Building, Miami’s first<br />

“skyscraper,” were built between 1912 and<br />

1917. Other buildings from this era include the<br />

Seminole [1913] and McCroy Hotels [1906] on<br />

Flagler Street between Miami and NE First<br />

Avenues. They still retain their distinctive pro -<br />

files even though some alterations have<br />

occurred as pioneer hotels turned into ten-cent<br />

and department stores.<br />

The most pristine vernacular arcaded storefront<br />

is at North Miami Avenue between<br />

Fourth and Fifth Streets. In 1991, preserva -<br />

tionists, citing Section 106 of the U.S. Federal<br />

Preservation Act, convinced the Federal<br />

Bureau of Prisons to retain and restore the front<br />

section of the entire block (Chaille Block and<br />

Dade Apartments) and incorporate it into the<br />

new Federal prison.<br />

Another unique pre-1920s building is Dr.<br />

James M. Jackson’s office (190 SE 12th<br />

Terrace), now the headquarters of Dade<br />

Heritage Trust. Originally built in 1905, the<br />

office, along with Dr. Jackson’s house, was<br />

moved from Flagler Street to its present site<br />

in 1917. A few blocks from Dr. Jackson’s<br />

office is Southside School [1914]. This little<br />

jewel, designed by Walter DeGarmo, sparkles<br />

amidst the rapidly re-developing Brickell<br />

area. Behind it sits the original Miami High<br />

School [1904] moved there in 1911 to<br />

become the original Southside School.<br />

Although now a private residence, the careful<br />

observer can recognize the typical school<br />

house windows and bell tower.<br />

The Miami River Inn, a restored complex<br />

of buildings in Riverside (Little Havana), one<br />

of Miami’s first suburbs, also recalls pre-<br />

Boom Miami. Little Havana has the largest<br />

concentration of Miami’s distinctive, coralrock-decorated<br />

vernacular bungalows and<br />

Mission style homes and storefronts. It is an<br />

important historic district waiting to happen.<br />

Spring Garden, another riverfront subdivi -<br />

sion [1918], is already a City of Miami<br />

<strong>Historic</strong> District.<br />

In this same era, when the twentieth century<br />

and the City of Miami were both<br />

teenagers, national industrialists and capitalists<br />

as well as a few well-heeled locals turned<br />

Brickell Avenue and Main Highway into<br />

Millionaire’s Row. Although most of these large<br />

estates have been broken up, a few notable<br />

ones remain. In 1916, James Deering of<br />

International Harvester completed his palatial<br />

Villa Vizcaya on former Brickell hammock<br />

land. It remains Miami’s most spectacular<br />

dwelling and is listed as a national landmark.<br />

A year later, John Bindley, president of<br />

Pittsburgh Steel, built the beautiful El Jardin,<br />

now Carrolton School, on Main Highway.<br />

Together these two buildings launched South<br />

Florida’s love affair with Mediterranean<br />

Revival architecture.<br />

A postcard from 1910 illustrates a view of Miami looking west from what is now 27th Avenue toward the drainage canal for<br />

the Miami River and the Everglades. (COURTESY OF THE COLLECTION OF BOB CARR)<br />

12 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

Just east of Vizcaya, one can still get a<br />

glimpse of what Millionaire’s Row looked like<br />

more than 70 years ago. Villa Serena, built in<br />

1913 by three-time presidential candidate and<br />

U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan,<br />

sits next to the home of his cousin and former<br />

Florida governor William Sherman Jennings.<br />

In recent years, several magnificent new mansions<br />

have joined these and other historic<br />

homes, giving the street a singular ambience<br />

reminiscent of earlier halcyon days.<br />

Because law segregated the races, African-<br />

American communities developed separately.<br />

White Miami had its downtown, and African-<br />

American Miami had its Colored Town or<br />

Overtown. This vibrant African-American<br />

commercial and residential district developed<br />

around Avenue G, now NW Second Avenue.<br />

Cut up and mowed down in the 1960s by<br />

urban renewal and expressways, Overtown is<br />

making a comeback through efforts of the<br />

Black Archives History and Research<br />

Foundation, Inc., founded by Dr. Dorothy<br />

Fields. The restored Dr. William A. Chapman<br />

House [1923], the D.A. Dorsey House [1910-<br />

1914] and the Lyric Theater [1910-1914], as<br />

well as several historic churches, will give<br />

Overtown a new beginning as a <strong>Historic</strong><br />

Folklife Village.<br />

As Miami grew, Overtown became over -<br />

crowded but was not allowed to expand its<br />

borders. In response, developers created new<br />

black suburbs in Liberty City and Brownsville.<br />

Today, preservationists are also focusing on<br />

preserving the heart of these historic African-<br />

American neighborhoods.<br />

The 1920s brought dramatic change to the<br />

Magic City. In the span of just a few years, Miami<br />

quadrupled its population and evolved from a<br />

small southern town into a big city. The Boom<br />

with a capital “B” became a national phenomenon<br />

and its wild, no-holds-barred, get-rich-quick<br />

atmosphere attracted hordes of people from all<br />

over. As a result of the huge quantity of buildings<br />

from this era, Miami’s oldest and largest concentration<br />

of historic structures dates from the Boom.<br />

Notable downtown buildings include: the Miami<br />

News Tower [Freedom Tower-1925], the<br />

Olympia Theater and Office Building [Gusman<br />

Theater-1926], the Ingraham Building [1927],<br />

the Dade County Courthouse [1928], Central<br />

Baptist Church [1927] Gesu Church [1925],<br />

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral [1926], the Miami<br />

Woman’s Club [1925] and the Scottish Rite<br />

Temple [1922]. The recently restored Martin<br />

Hampton-designed Congress Building [1925] is<br />

the latest historic building to make a come back<br />

and once again brighten the skyline.<br />

One cannot write about the Boom without<br />

highlighting George Merrick, who had more to<br />

do with its creation than anyone else. In<br />

Merrick’s Coral Gables, one can find the greatest<br />

number of Boom-time (and new)<br />

Mediterranean Revival style buildings in<br />

Miami-Dade County. This is due to the fact that<br />

Coral Gables has made great strides in preserving<br />

this legacy and was the first community to<br />

pass a preservation ordinance [1973].<br />

Merrick, who moved to the area with his<br />

family in 1899 as a 13-year-old boy, grew up<br />

on his family’s grapefruit plantation. His talented<br />

mother Althea designed their rock<br />

home, which they named Coral Gables<br />

[1907]. After his father’s death in 1911,<br />

Merrick took over the groves and began planning<br />

his dream suburb around a Spanish/<br />

Mediterranean theme.<br />

In November 1921, after years of thoughtful<br />

study, Merrick sold the first lots in what became<br />

South Florida’s first planned city. For the next<br />

seven years, Merrick’s firm hand kept the Gables<br />

on track. With a strong belief that making a city<br />

beautiful was more important than making<br />

money, he spent millions on architectural fea -<br />

tures such as entry gates, plazas, fountains and<br />

major public and corporate buildings that set the<br />

tone for the whole community. Every structure,<br />

every color selection, every awning had to pass a<br />

strict architectural board made up of Merrick, his<br />

uncle Denman Fink and architect Phineas Paist.<br />

Although some of the wonderful small commercial<br />

buildings have been lost, Coral Gables is still<br />

know for its singular landmarks like the spectacular<br />

Biltmore Hotel [1926], The Colonnade<br />

[1926], The Douglas Entrance [Puerta del Sol,<br />

1927], City Hall [1928], Coral Gables<br />

Congregational Church [1924], Coral Gables<br />

Elementary School [1923] and the Venetian Pool<br />

[1924], as well as thousands of private homes<br />

and several themed villages.<br />

Merrick was not the only developer caught<br />

up in creating themed suburbs. James Bright<br />

and aviation luminary Glenn Curtiss created<br />

Hialeah and Miami Springs around a Mission<br />

and Pueblo Revival theme. Curtiss also built<br />

Opa-locka based on the Arabian Nights. Opalocka<br />

remains a unique piece of Boom-time<br />

fantasy architecture as seen in its restored City<br />

Hall and other designated buildings.<br />

The Boom also created other distinctive<br />

suburbs in the northeast quarter. Miami<br />

Shores, Coral Gables’ greatest rival, and<br />

Fulford by the Sea [North Miami Beach]<br />

were later incorporated into separate cities.<br />

Morningside, the City of Miami’s first his -<br />

toric district, is a planned bayfront development<br />

characterized by many beautiful<br />

Mediterranean Revival homes. Its wellorganized<br />

group of enthusiasts has returned<br />

it and Bayshore, to the south, into two of the<br />

City of Miami’s most beautiful neighbor -<br />

hoods. Nearby, the early suburb and onetime<br />

Town of Buena Vista is also being<br />

restored to its former glory. Thanks to the<br />

efforts of dedicated preservationists, restoration<br />

fever is spreading up Biscayne<br />

Boulevard as one historic neighborhood<br />

after another makes its comeback.<br />

Miami entered the Great Depression<br />

ahead of the rest of the nation. The Florida<br />

Boom and crash were a dress rehearsal for<br />

the stock market debacle that followed a few<br />

years later. Like the rest of America, Miami<br />

benefited by the numerous New Deal pro -<br />

grams created in the 1930s to help the nation<br />

out of depression. The Civil Conservation<br />

Corps built Matheson Hammock, Greynolds<br />

Park and Fairchild Tropical Garden with<br />

unique rock walls, pavilions and architectural<br />

features. The Public Works Administration<br />

built Liberty Square and several Miami<br />

schools, including Shenandoah Junior High<br />

and Miami Shores and Coral Way<br />

Elementaries. The old Coral Gables Police<br />

and Fire Station and the Miami Beach Post<br />

Office were but two of the public buildings<br />

constructed by the PWA. Uncle Sam also<br />

hired artists to beautify the new public buildings.<br />

Denman Fink, uncle of George Merrick<br />

and one of the principals in the design of<br />

Coral Gables, created one of the most cher -<br />

ished works—a mural in the Central<br />

Courtroom of the U.S. Federal Courthouse<br />

designed by Phineas Paist [1931].<br />

By the mid-1930s, when the rest of the nation<br />

was still wallowing in the slough of depression,<br />

Miami was on the way out. The Mediterranean<br />

Revival style architecture that marked the Boom<br />

was on the way out as well. “Art Moderne” and<br />

“Art Deco” were the new style of architecture in<br />

America. The Bessemer Corporation introduced<br />

the style in Miami as part of its ambitious<br />

Biscayne Boulevard development. Billed as<br />

Miami’s “Fifth Avenue,” this project was one of the<br />

few bright spots in the late 1920s. Today the Sears<br />

Tower [1929] and the Mahi Shrine Temple<br />

Headquarters [Boulevard Shops-1930] are the<br />

most important remaining buildings of this<br />

development. Other notable Art Deco buildings<br />

in Downtown Miami include the beautiful Alfred<br />

I. Dupont Building [1938], Walgreens (now<br />

Sports Authority) [1936] and Burdine’s [1936].<br />

The ultimate flowering of local Art Deco,<br />

however, occurred on Miami Beach.<br />

Despite the Depression, the 1930s brought<br />

new life to Miami Beach. No more ornate excess<br />

of 1920s consumption like the long-gone<br />

Nautilus, Flamingo and Roney Plaza; the new<br />

style was spare, sleek, inexpensive and thor -<br />

oughly modern. Most of all, Miami Beach’s<br />

CHAPTER II ✧ 13

tropical answer to Art Deco was fun. Glass<br />

block and murals, cavorting mermaids, danc -<br />

ing dolphins and smiling seahorses etched into<br />

glass with jig-saw puzzle floors in sleek terrazzo<br />

were all wrapped up in undulating facades<br />

pierced by a thousand portholes. Swaying palm<br />

fronds, rolling surf, and the famous Miami<br />

moon completed the scene and made it seem<br />

like Art Deco had been created especially for<br />

Miami Beach. Until World War II brought an<br />

end to the fun, Miami Beach was issuing building<br />

permits for new hotels at the rate of one<br />

every three days. Today, these small South<br />

Beach hotels and apartments make up Miami<br />

Beach’s famed Art Deco District.<br />

After the war, Miami Beach took on a new<br />

style (now called Miami Modern or MiMo) that<br />

reached its peak with the work of Morris<br />

Lapidus in the 1950s. For a while, the grandiose<br />

Fontainebleau, Eden Roc, Doral and Americana<br />

hotels as well as the fantasy motels on North<br />

Beach kept the tourists coming to Miami Beach.<br />

The beginning of what we call sprawl also<br />

came at war’s end as hundreds of thousands<br />

of GI’s came to Miami to start a new life.<br />

These post-war subdivisions are now reach -<br />

ing historic status along with other commercial<br />

buildings from that era. Hoping to avoid<br />

what happened in the past, preservationists<br />

are currently looking carefully at these<br />

resources to help make thoughtful decisions<br />

for their future.<br />

The 1960s brought even more change to<br />

Greater Miami. But then Miamians had always<br />

been accustomed to change. The city’s entire<br />

history had been written in short paragraphs.<br />

No one, however, was prepared for the<br />

changes the ’60s would bring.<br />

After Fidel Castro took over Cuba in 1959, a<br />

continuous stream of exiles flowed into Miami.<br />

When Castro announced his Communist leanings,<br />

the stream became a flood as hundreds of<br />

thousands of Cubans fled their homeland. The<br />

Cubans, often destitute, had to start their lives<br />

over again in a foreign land. They moved into the<br />

low-rent, older, declining neighborhoods of<br />

Riverside and Shenandoah, breathing in new life.<br />

Before long, the old Tamiami Trail became Calle<br />

The road from Miami to Cocoanut Grove was once a verdant, but lonely, trail. (COURTESY OF THE FLORIDA STATE ARCHIVES)<br />

Ocho, “Little Havana’s” Main Street. The Tower<br />

Theater [1926] was the gathering place and<br />

became the first theater in Miami to have Spanish<br />

sub-titles. Neighboring stores sported Spanish<br />

signs, yet the businesses remained remarkably<br />

similar to the pre-Cuban days and the whole area<br />

kept its strong historic Mom-and-Pop flavor.<br />

As “Little Havana” becomes a diverse “Latin<br />

Quarter,” and fast food and other chain “any -<br />

place” businesses move in, the visual landmarks,<br />

no matter how humble, of where the Cuban<br />

transformation of Miami began are disappearing.<br />

Like Henry Flagler’s Miami that vanished during<br />

the Boom, Little Havana will also pass into oblivion<br />

unless effort is made to preserve at least part<br />

of it as it was when the Cubans arrived. How well<br />

we know from past experience that once we can<br />

no longer see our history, we quickly forget it.<br />

We can learn about the past in history<br />

books or meet it face to place in historic buildings,<br />

schools, churches, homes and neighborhoods.<br />

Sadly, we will never really appreciate<br />

our history and become “placed people” if<br />

there is no place left to remember.<br />

Arva Moore Parks is a native Miamian who has spent more than 25 years researching and writing about her favorite city. But more than an historian, Parks is a<br />

leader, participating in many different arenas, learning firsthand what Miami and its people are all about. She is known as an indefatigable advocate for historic<br />

preservation, and her leadership has helped save many important landmarks. She has held both local and national preservation offices, and in 1995 President Bill<br />

Clinton appointed her to the Federal Advisory Council on <strong>Historic</strong> Preservation.<br />

She is author of numerous award-winning books, films and articles on Miami, including Miami: The Magic City, which was named the official history of the City of Miami,<br />

and Our Miami: The Magic City, a 60-minute video which won a Florida Emmy. Through Arva Parks & Company she is also known for her historical research and interpretive<br />

design, which includes Coral Gables’ Colonnade Hotel and the Harry Truman Little White House in Key West.<br />

She has been widely honored for her activism and her writing. The Coral Gables Chamber of Commerce named her their Robert B. Knight Outstanding Citizen in<br />

1983, and in 1985 she was inducted into the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame. In 1996, she was listed in the City of Miami Centennial Women’s Hall of Fame, and Barry<br />

University awarded her an Honorary Doctor of Laws. In 1997, the University of Florida named her one of 47 Women of Achievement honored at the fall celebration<br />

of 50 years of co-education.<br />

14 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

The Brickell family, early pioneers who played key roles in shaping Miami’s future, pose on the porch of their stately home. William B. Brickell is seated on the veranda, so the photograph was<br />

taken before 1908, the year he died. The Brickell mansion was located on the south bank of the Miami River, where the Sheraton Biscayne Bay Hotel is today, and the grounds included what is<br />

now Brickell Park and the Miami Circle Archeological Site. (COURTESY OF THE FLORIDA STATE ARCHIVES)<br />

VOICES FROM THE PAST<br />

B Y H ELEN M UIR<br />

On the doorstep of the 21st century, we<br />

pause in Miami-Dade to consider how we<br />

arrived here. Voices from the Past ring in<br />

our ears.<br />

Certainly Mary Brickell and her husband,<br />

William Barnwell Brickell, left the family<br />

mark on South Florida. The story of all the<br />

Brickell daughters, none of whom married,<br />

holds elements of drama. Perhaps surprisingly,<br />

it is the words of their last offspring, known<br />

as Miss Maude, that linger in my mind.<br />

Miss Maude was christened Maudenella.<br />

“You know lawyers,” she explained. “Can’t<br />

tell them anything. They changed it to<br />

Maude E.” In any case, as Maudenella or<br />

Maude E., it was she who took over the care<br />

of the rose garden at the Royal Palm Hotel<br />

during the long hot summers because she<br />

fell in love with the roses and was rewarded<br />

with blooms for her own bedroom.<br />

Early in the 1950s I sat with Miss<br />

Maude on the wide porch of the house<br />

which has been described as a mansion. In<br />

my sense, the house fell short of the term<br />

except for the exterior view. In any case, I<br />

was questioning her as to accurate names<br />

of the Brickell “girls.” She gave them to me:<br />

Alice Amy, Edith Mary Kate and Belle<br />

Gertrude (Emma died in childhood of<br />

spinal meningitis).<br />

None of these Brickell daughters enjoyed<br />

anything like a social life as the term is<br />

understood today. The men in the family<br />

were sent away to school, but Mary Brickell<br />

once declared it was neither necessary nor<br />

appropriate for “the girls” to be so endowed.<br />

In our conversations we never touched on<br />

the body of myth that grew up about The<br />

Brickells, but one day I was permitted to enter<br />

the old place. Our small son, who accompanied<br />

me on these visits, was refused admittance<br />

to the interior of the house and was relegated<br />

to wait in the garden. Toby was advised<br />

to amuse himself by watching the monkeys in<br />

the vine covered trees. Meanwhile, the house<br />

CHAPTER III ✧ 15

enter the old place. Our small son, who<br />

accompanied me on these visits, was refused<br />

admittance to the interior of the house and<br />

was relegated to wait in the garden. Toby was<br />

advised to amuse himself by watching the<br />

monkeys in the vine covered trees.<br />

Meanwhile, the house was filled with dogs<br />

and cats and was a welter of confusion.<br />

Difficult to envision were “lavish parties” as<br />

described in earlier reports. The restrained<br />

words of Commodore Ralph M. Munroe,<br />

commenting on the glamorous history of the<br />

Brickells as described by Brickell himself,<br />

come to mind: “Brickell could not resist dramatic<br />

exaggeration.”<br />

Left to us is the image of Miss Belle carrying<br />

home heavy sacks of groceries on a<br />

scorching hot day all the way from Buena<br />

Vista because “a fellow owed her money” and<br />

she “was taking it out in trade.” Of course, we<br />

also have the picture of Miss Edith with a<br />

satchel of cash, doling it out to those in need.<br />

One day when Miss Maude went to sit<br />

on a neighbor’s porch a fire engine came<br />

charging into the area. “Wasting the taxpayer’s<br />

money,” Miss Maude said. A man<br />

came running down the street, swinging his<br />

arms in excitement. “One of the Brickell<br />

girls stepped on a live wire and got cut<br />

spang in two” he exclaimed. That was the<br />

end of Miss Alice, the only one with an<br />

education because she got it in Cleveland<br />

before the move to the Bay country.<br />

Miss Alice had organized Sunday School<br />

out under the orange trees to which<br />

Seminoles often came, had taught school at<br />

Lemon City and had been the official postmistress<br />

attached to the family trading post.<br />

It was during the Boom that Miss<br />

Maude suffered a disillusionment of substance<br />

when a fine looking, smooth-talking<br />

fellow to whom she rented a house swindled<br />

her out of $320,000 (in cash!) in<br />

order to “corner the market on copper.”<br />

The fellow had two names, it turned out,<br />

after the county solicitor’s office heard<br />

about the matter and investigated.<br />

Miss Maude’s final years as the sole<br />

occupant of the old Brickell house were<br />

fully occupied with her own funeral<br />

arrangements and before that with arranging<br />

burial places for others in the family.<br />

The funeral director reported that for fifteen<br />

years she concerned herself with how<br />

her hair should be arranged.<br />

When she died in 1960, the body lay in<br />

state at a Coral Gables funeral parlor in the<br />

bronze casket she selected, before being<br />

removed to Woodlawn Cemetery. Her official<br />

age at death was 89, three years older than her<br />

age as she gave it to me back in the 1950s.<br />

✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧<br />

Eunice Merrick said that when she and<br />

her husband, George Edgar Merrick, decided<br />

to build their own residence in the City<br />

of Coral Gables, which he was creating, her<br />

mother showed concern. “Won’t you be terribly<br />

lonely out there all by yourself?” was<br />

the way the wife of Alfred Peacock put it.<br />

It held an echo of the Charles and Isabella<br />

Peacock decision, after their first glimpse of<br />

what would be called Coconut Grove, to<br />

move up to the mouth of the Miami River<br />

where there would be the Brickells, the Duke<br />

of Dade and the Lovelace family. Of course,<br />

they did later move to Coconut Grove where<br />

the brother of Charles, “Jolly Jack” Peacock,<br />

preceded them, and Isabella earned the title<br />

of “the Mother of Coconut Grove.”<br />

The day we chatted about pioneering<br />

experiences with Mrs. Alfred Peacock she<br />

was in her eighties, keeping a low-key<br />

appearance and preparing to celebrate<br />

Thanksgiving with daughter Eunice<br />

Merrick. The conversation turned to early<br />

Thanksgiving celebrations in Coconut<br />

Grove and, in particular, the 1887 occasion<br />

when the early settlers gathered for a program<br />

in the log cabin schoolhouse on the<br />

bluff looking down over Dinner Key.<br />

They were there because Euphemia<br />

Frow had threatened to leave the Grove if a<br />

school was not provided for the children.<br />

Lillian Frow Peacock recalled that she recited<br />

“the First Thanksgiving.” The Joseph<br />

Frows beamed at their offspring, and her<br />

sister, Grace, and brothers, Charlie and Joe,<br />

clapped their hands politely.<br />

They had walked over “the trail” to the<br />

thatch-covered cabin in the late afternoon.<br />

There were no refreshments because everyone<br />

had sat down to a hearty midday dinner.<br />

There were ten pupils in the cabin<br />

schoolhouse that day: the Frows, Anne<br />

Tavernier and Beverly, who were the children<br />

of John Thomas (“Jolly Jack”)<br />

Peacock, and Eddie, John, James (“Tiny”)<br />

and Renie Pent.<br />

✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧<br />

The voice of one of the most colorful<br />

characters to be identified with Miami Beach<br />

has been all but stilled despite the splash he<br />

made in the spring and summer of 1935.<br />

Floyd Gibbons was a legendary figure long<br />

before he appeared on a visit to the Beach.<br />

As a war correspondent for the Chicago<br />

Tribune in Europe during World War I,<br />

Floyd Gibbons was awarded the Croix de<br />

Guerre and was made a chevalier of the<br />

Legion of Honor. He wore an eye patch<br />

after losing an eye in the Battle of Château<br />

Thierry, and,in the 1930s, when he arrived<br />

in Florida, he was a radio performer billed<br />

as the “Headline Hunter.”<br />

He was a star, even for those ignorant of<br />

his background, which included riding with<br />

Pancho Villa in 1915 in the Mexican<br />

Revolution and with General Pershing the<br />

following year and writing The Red Knight of<br />

Germany, the popular biography of German<br />

fighter ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen,<br />

and a successful novel, The Red Napoleon.<br />

Gibbons’ entrance on the Miami scene<br />

was applauded by everyone from Mayor<br />

Red Snedigar to newsmen reaching for stories,<br />

and the Headline Hunter did not fail.<br />

He fell in love with Miami and almost at<br />

once purchased a North Bay Road home,<br />

sending word to his sister, Zelda, to leave<br />

Boston and the popular dress shop she and<br />

her husband, Theodore Mayer, ran, to<br />

come help furnish it. When it was completed,<br />

he gave a big party for all those who<br />

had been knocking on his door.<br />

The next day as he sat under a palm tree<br />

recuperating, his eye flew open at the<br />

sound of a bullhorn pointing out his presence<br />

from a passing boat. A tourist guide<br />

was telling the world that “Here is the<br />

house purchased by Floyd Gibbons—and<br />

there he sits!”<br />

A cherished memory of mine is of a small<br />

dinner party on top of the Deauville Hotel. It<br />

brought together Eddie Rickenbacker, among<br />

other friends. There was no air conditioning at<br />

that time, but natural breezes from the ocean<br />

helped make it an unforgettable evening.<br />

Gibbons’ presence had brought Ernest<br />

Hemingway up from Key West for fishing<br />

expeditions, with Jed Kiley making it a trio.<br />

Once upon a time the three had fraternized<br />

in Paris. They were reunited in South<br />

Florida at a time gone but not forgotten by<br />

those who lived through it.<br />

A call to return to the earlier role of war<br />

correspondent put an end to this idyllic<br />

period. Gibbons’ death in 1939 at his<br />

Pennsylvania farm wrote finis to the life of<br />

this legendary man.<br />

✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧<br />

Mrs. Jack Peacock offered a large dinner<br />

bell to Mrs. Stephen van Rensselaer<br />

Carpenter, the president of the Housekeeper’s<br />

Club, when the railroad extension began<br />

pushing in the direction of Coconut Grove.<br />

There were five daughters dwelling with their<br />

mother in the large house overlooking<br />

Biscayne Bay. Del, the son in the family, was<br />

off working on the railroad supply boat.<br />

People had begun to lock their doors,<br />

16 ✧ MIAMI’S HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOODS

and a warning bell could well prove to be a<br />

needed protective device. One daughter,<br />

Miss Hattie, had her own ideas for self protection.<br />

This schoolteacher, on her way to<br />

becoming the second principal of Miami<br />

High School, placed a pistol in the basket<br />

of her bicycle.<br />

One morning as she pedaled through<br />

the Punch Bowl District, a number of tough<br />

looking workmen blocked her way. Miss<br />

Hattie described how she dealt with the situation:<br />

“I lifted the pistol from the basket in<br />

one hand, and greeted the men. I smiled<br />

and said ‘Good morning boys.’” Laughter<br />

broke out among the line of extension<br />

workers and Miss Hattie continued on her<br />

way. No hesitation, ever, in the way Miss<br />

Hattie would proceed.<br />

She loved Miami High School. But<br />

when the School Board took steps she considered<br />

detrimental to the standards she<br />

held, she up and quit. But she wasn’t finished<br />

by any means. She moved over to<br />

Miami’s first newspaper, The Metropolis, to<br />

write editorials.<br />

Miss Hattie offered a wealth of insight<br />

and information to me in writing Miami<br />

USA, and, when it was brought out in 1953,<br />

I quite properly signed one of the first copies<br />

to her. Her response was characteristic. She<br />

sat down and wrote a two-page review of the<br />

book and sent it off to Henry Holt in New<br />

York, which had published the volume.<br />

The death of Miss Hattie Carpenter was<br />

a personal sorrow to me. It occurred one<br />

day as she bent over a garden bed attending<br />

to necessary weeding.<br />

✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧ ✧<br />

During the first half of the 20th century, a<br />

man named Ben J. Fisher applied himself to<br />

the building of rock walls in Coconut Grove.<br />

Today, gazing at these lovely monuments to<br />

Ben, I recall the man and his many sides.<br />

Ben was black in a time when the word<br />

used was “colored.” He came into our family’s<br />

life when he built one of his walls for us.<br />

He was meticulous about the shape of each<br />

piece placed into the structure and won our<br />

admiration for his workmanlike precision<br />

and artistry.<br />

Our two small daughters formed an<br />

admiring audience for his efforts and the<br />

building of that wall constituted a happy<br />

time for all of us. One day when he heard<br />

that we were having a party he came to ask<br />

Floyd Gibbons, a dashing war correspondent, author and radio announcer, made headlines happen when he visited<br />

Miami in 1935. (COURTESY OF HELEN MUIR)<br />

if he could come and “help.” I said “yes,”<br />

not knowing what to expect, but when he<br />

arrived he presented a dazzling appearance.<br />

He was dressed in black trousers and a<br />

spanking white jacket and black necktie.<br />

He did more than “help.” He was an elegant<br />

addition to the event. He asked to<br />

serve the drinks and I ended up teaching<br />

him how to mix a proper dry martini. His<br />

eyes shone as he assured me “I get it. It’s<br />

just like mixing cement.”<br />

One evening toward dusk I received an<br />

unexpected telephone call from Ben. “Mrs.<br />

Muir, go get yourself a little drink and we’ll<br />

talk,” he urged. He continued to keep in<br />

touch and, several days following the 1944<br />

sudden death of our second daughter, he<br />

came to the house and made his presence<br />

known in a particular way.<br />

While my husband and I sat on the<br />

back porch overlooking the garden, Ben<br />

went to the garage and brought out a manual<br />

lawn mower. Understand, this was not<br />

a tool with which Ben associated himself,<br />

having advanced into an artisan role. We<br />

watched him slowly move the lawn mower<br />

back and forth. Finally, he stopped, and<br />

leaning against the pine tree under which<br />

our little girls had played, he said these<br />

words: “You can’t see her but she’s present<br />

in the Lord.”<br />

Life moved along and the day came<br />

when Ben was dying in his little house in<br />

Coconut Grove. I took our son and his<br />

Helen Muir is a longtime resident of Coconut Grove. She came to Miami in 1934 from the New York Journal to direct publicity at the Roney Plaza Hotel on Miami<br />

Beach. She was a columnist for both The Miami Herald and the Miami News and wrote for the Saturday Evening Post, Nation’s Business, Woman’s Day and This<br />

Week magazine. She is the author of numerous books, including MIAMI USA, The Biltmore: Beacon for Miami; and Frost in Florida. A leading supporter of public<br />

libraries, she has been honored with the Spirit of Excellence Award and has been named to the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame.<br />

CHAPTER III ✧ 17

The Halycon Hotel, built in 1905, was designed by Stanford White and constructed of native oolitic limestone. It was demolished in 1938,<br />

and the Alfred I. Dupont Building was built on its site. (COURTESY OF DADE HERITAGE TRUST)<br />

MIAMI<br />

B Y A RISTIDES J. MILLAS<br />

In 1870, William Brickell and his family<br />

arrived at Fort Dallas. He had decided to settle<br />

in this new country and bought two tracts of<br />

land south of the Miami River, of 640 acres<br />

each. The land was originally acquired under<br />

the Settlement Act of Congress. Mr. Brickell, a<br />

former resident of Cleveland, Ohio, built and<br />

operated on the south side of the river Miami’s<br />

first store, the only one in this vicinity until<br />

after the city was incorporated. He also built his<br />

home on what is now known as Brickell Point.<br />

In 1880, Mrs. Julia Tuttle and her ailing<br />