Aziz Art January 2019

History of art(west and middle east)- contemporary art ,art ,contemporary art ,art-history of art ,iranian art ,iranian contemporary art ,famous iranian artist ,middle east art ,european art

History of art(west and middle east)- contemporary art ,art ,contemporary art ,art-history of art ,iranian art ,iranian contemporary art ,famous iranian artist ,middle east art ,european art

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Aziz</strong> <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>January</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Abbas Kowsari<br />

Parastou Forouhar<br />

Louise Bourgeois

1-Louise Bourgeois<br />

16-Parastou<br />

Forouhar<br />

21-Abbas Kowsari<br />

Director: <strong>Aziz</strong> Anzabi<br />

Editor : Nafiseh<br />

Yaghoubi<br />

Translator : Asra<br />

Yaghoubi<br />

Research: Zohreh Nazari<br />

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois 25<br />

December 1911 – 31 May 2010<br />

was a French-American artist.<br />

Although she is best known for<br />

her large-scale sculpture and<br />

installation art, Bourgeois was also<br />

a prolific painter and printmaker.<br />

She explored a variety of themes<br />

over the course of her long career<br />

including domesticity and the<br />

family, sexuality and the body, as<br />

well as death and the<br />

subconscious.<br />

These themes connect to events<br />

from her childhood which she<br />

considered to be a therapeutic<br />

process.<br />

Although Bourgeois exhibited with<br />

the Abstract Expressionists and her<br />

work has much in common with<br />

Surrealism and Feminist art, she<br />

was not formally affiliated with a<br />

particular artistic movement.<br />

Early life<br />

Bourgeois was born on 25<br />

December 1911 in Paris, France.<br />

She was the second child of three<br />

born to parents<br />

Joséphine Fauriaux and Louis<br />

Bourgeois. She had an older sister<br />

and a younger brother.Her parents<br />

owned a gallery that dealt primarily<br />

in antique tapestries. A few years<br />

after her birth, her family moved<br />

out of Paris and set up a workshop<br />

for tapestry restoration below their<br />

apartment in Choisy-le-Roi, for<br />

which Bourgeois filled in the<br />

designs where they had become<br />

worn.<br />

The lower part of the tapestries<br />

were always damaged which was<br />

usually the characters' feet and<br />

animals' paws. Many of Bourgeois's<br />

works have extremely fragile and<br />

frail feet which could be a result of<br />

the former.<br />

In 1930, Bourgeois entered the<br />

Sorbonne to study mathematics<br />

and geometry, subjects that she<br />

valued for their stability, saying "I<br />

got peace of mind, only through<br />

the study of rules nobody could<br />

change."<br />

Her mother died in 1932, while<br />

Bourgeois was studying<br />

mathematics. Her mother's death<br />

inspired her to abandon<br />

mathematics and to begin studying<br />

art.<br />

1

She continued to study art by<br />

joining classes where translators<br />

were needed for English-speaking<br />

students, in which those<br />

translators were not charged<br />

tuition. In one such class Fernand<br />

Léger saw her work and told her<br />

she was a sculptor, not a painter.<br />

Bourgeois graduated from the<br />

Sorbonne 1935. She began<br />

studying art in Paris, first at the<br />

École des Beaux-<strong>Art</strong>s and<br />

École du Louvre, and after 1932<br />

in the independent academies<br />

of Montparnasse and<br />

Montmartre such as Académie<br />

Colarossi, Académie Ranson,<br />

Académie Julian, Académie de la<br />

Grande Chaumière and with<br />

André Lhote, Fernand Léger, Paul<br />

Colin and Cassandre.<br />

Bourgeois had a desire for firsthand<br />

experience, and frequently<br />

visited studios in Paris, learning<br />

techniques from the artists and<br />

assisting with exhibitions.<br />

Bourgeois briefly opened a print<br />

store beside her father's tapestry<br />

workshop. Her father helped her<br />

on the grounds that she had<br />

entered into a commerce-driven<br />

profession.<br />

Bourgeois emigrated to New York<br />

City in 1938. She studied at the <strong>Art</strong><br />

Students League of New York,<br />

studying painting under Vaclav<br />

Vytlacil, and also producing<br />

sculptures and prints.<br />

"The first painting had a grid: the<br />

grid is a very peaceful thing<br />

because nothing can go wrong ...<br />

everything is complete. There is no<br />

room for anxiety ... everything has<br />

a place, everything is welcome."<br />

Bourgeois incorporated those<br />

autobiographical references to her<br />

sculpture Quarantania I, on display<br />

in the Cullen Sculpture Garden at<br />

the Museum of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, Houston.<br />

Middle years<br />

For Bourgeois the early 1940s<br />

represented the difficulties of a<br />

transition to a new country and the<br />

struggle to enter the exhibition<br />

world of New York City. Her work<br />

during this time was constructed<br />

from junkyard scraps and driftwood<br />

which she used to carve upright<br />

wood sculptures.

The impurities of the wood were<br />

then camouflaged with paint,<br />

after which nails were employed<br />

to invent holes and scratches in<br />

the endeavor to portray some<br />

emotion. The Sleeping Figure is<br />

one such example which depicts a<br />

war<br />

figure that is unable to face the<br />

real world due to vulnerability.<br />

Throughout her life, Bourgeois's<br />

work was created from revisiting<br />

of her own troubled past as she<br />

found inspiration and temporary<br />

catharsis from her childhood years<br />

and the abuse she suffered from<br />

her father. Slowly she developed<br />

more artistic confidence, although<br />

her middle years are more opaque,<br />

which might be due to the<br />

fact that she received very little<br />

attention from the art world<br />

despite having her first solo show<br />

in 1945.She became an American<br />

citizen in 1951.<br />

In 1954, Bourgeois joined the<br />

American Abstract <strong>Art</strong>ists Group,<br />

with several contemporaries,<br />

among them Barnett Newman<br />

and Ad Reinhardt. At this time she<br />

also befriended the artists Willem<br />

de Kooning, Mark Rothko,<br />

and Jackson Pollock.<br />

As part of the American Abstract<br />

<strong>Art</strong>ists Group, Bourgeois made the<br />

transition from wood and upright<br />

structures to marble, plaster and<br />

bronze as she investigated concerns<br />

like fear, vulnerability and loss of<br />

control. This transition was a<br />

turning point. She referred to her<br />

art as a series or sequence closely<br />

related to days and circumstances,<br />

describing her early work as the<br />

fear of falling which later<br />

transformed into the art of falling<br />

and the final evolution as the art of<br />

hanging in there. Her conflicts in<br />

real life empowered her to<br />

authenticate her experiences and<br />

struggles through a unique art<br />

form. In 1958, Bourgeois and her<br />

husband moved into a terraced<br />

house at West 20th Street, in<br />

Chelsea, Manhattan, where she<br />

lived and worked for the rest of her<br />

life.<br />

Despite the fact that she rejected<br />

the idea that her art was feminist,<br />

Bourgeois's subject was the<br />

feminine. Works such as Femme<br />

Maison (1946-1947), Torso selfportrait<br />

(1963-1964), Arch of<br />

Hysteria (1993), all depict the<br />

feminine body.

In the late 1960's, her imagery<br />

became more explicitly sexual as<br />

she explored the relationship<br />

between men and women and the<br />

emotional impact of her troubled<br />

childhood.<br />

Sexually explicit sculptures such<br />

as Janus Fleuri, (1968) show she<br />

was not afraid to use the female<br />

form in new ways. She has been<br />

quoted to say "My work deals with<br />

problems that are pre-gender,"<br />

she wrote. "For example,<br />

jealousy is not male or female."<br />

With the rise of feminism,<br />

her work found a wider audience.<br />

Despite this assertion, in 1976<br />

Femme Maison was featured on<br />

the cover of Lucy Lippard's book<br />

From the Center: Feminist Essays<br />

on Women's <strong>Art</strong> and became an<br />

icon of the feminist art movement.<br />

Later life<br />

In 1973, Bourgeois started<br />

teaching at the Pratt Institute,<br />

Cooper Union, Brooklyn College<br />

and the New York Studio School<br />

of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture.<br />

From 1974 until 1977, Bourgeois<br />

worked at the School of<br />

Visual <strong>Art</strong>s in New York where she<br />

taught printmaking and<br />

sculpture.She also taught for many<br />

years in the public<br />

schools in Great Neck, Long Island.<br />

In the early 1970s, Bourgeois would<br />

hold gatherings called "Sunday,<br />

bloody Sundays" at her home in<br />

Chelsea. These salons would be<br />

filled with young artists and<br />

students whose work would be<br />

critiqued by Bourgeois. Bourgeois<br />

ruthlessness in critique and her dry<br />

sense of humor lead to the naming<br />

of these meetings. Bourgeois<br />

inspired many young students to<br />

make art that was feminist in<br />

nature.However, Louise's long-time<br />

friend and assistant, Jerry Gorovoy,<br />

has stated that Louise considered<br />

her own work "pre-gender".<br />

Bourgeois aligned herself with<br />

activists and became a member of<br />

the Fight Censorship Group, a<br />

feminist anti-censorship collective<br />

founded by fellow artist Anita<br />

Steckel. In the 1970s, the group<br />

defended the use of sexual imagery<br />

in artwork.Steckel argued, "If the<br />

erect penis is not wholesome<br />

enough to go into museums, it<br />

should not be considered<br />

wholesome enough to go into<br />

women."

In 1978 Bourgeois was<br />

commissioned by the General<br />

Services Administration to create<br />

Facets of the Sun, her first public<br />

sculpture.The work was installed<br />

outside of a federal building in<br />

Manchester, New Hampshire.<br />

Bourgeois received her first<br />

retrospective in 1982, by the<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong> in New<br />

York City. Until then, she had been<br />

a peripheral figure in art whose<br />

work was more admired than<br />

acclaimed. In an interview with<br />

<strong>Art</strong>forum, timed to coincide with<br />

the opening of her retrospective,<br />

she revealed that the imagery in<br />

her sculptures was wholly<br />

autobiographical. She shared with<br />

the world that she obsessively<br />

relived through her art the trauma<br />

of discovering, as a child, that her<br />

English governess was also her<br />

father's mistress.<br />

Bourgeois had another<br />

retrospective in 1989 at<br />

Documenta 9 in Kassel,<br />

Germany.In 1993, when the Royal<br />

Academy of <strong>Art</strong>s staged its<br />

comprehensive survey of<br />

American art in the 20th century,<br />

the organizers did not consider<br />

Bourgeois's work of significant<br />

importance to include in the<br />

survey.However, this survey was<br />

criticized for many omissions, with<br />

one critic writing that "whole<br />

sections of the best American art<br />

have been wiped out" and pointing<br />

out that very few women were<br />

included. In 2000 her works were<br />

selected to be shown at the<br />

opening of the Tate Modern in<br />

London.In 2001, she showed at the<br />

Hermitage Museum.<br />

In 2010, in the last year of her life,<br />

Bourgeois used her art to speak up<br />

for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and<br />

Transgender (LGBT) equality. She<br />

created the piece I Do, depicting<br />

two flowers growing from one<br />

stem, to benefit the nonprofit<br />

organization Freedom to Marry.<br />

Bourgeois has said "Everyone<br />

should have the right to marry. To<br />

make a commitment to love<br />

someone forever is a beautiful<br />

thing."Bourgeois had a history of<br />

activism on behalf of LGBT equality,<br />

having created artwork for the AIDS<br />

activist organization ACT UP in<br />

1993.

Death<br />

Bourgeois died of heart failure on<br />

31 May 2010, at the Beth Israel<br />

Medical Center in<br />

Manhattan.Wendy Williams, the<br />

managing director of the Louise<br />

Bourgeois Studio, announced her<br />

death. She had continued to create<br />

artwork until her death, her last<br />

pieces being finished the week<br />

before.<br />

Bourgeois explores the relationship<br />

of a woman and the home. In the<br />

works, women's heads have been<br />

replaced with houses, isolating<br />

their bodies from the outside world<br />

and keeping their minds domestic.<br />

This theme goes along with the<br />

dehumanization of modern art.<br />

The New York Times said that her<br />

work "shared a set of repeated<br />

themes, centered on the human<br />

body and its need for nurture and<br />

protection in a frightening world."<br />

Her husband, Robert Goldwater,<br />

died in 1973. She was survived by<br />

two sons,<br />

Alain Bourgeois and Jean-Louis<br />

Bourgeois. Her first son, Michel,<br />

died in 1990.<br />

Work<br />

See also: List of artworks by Louise<br />

Bourgeois<br />

Femme Maison<br />

Main article: Femme Maison<br />

Femme Maison (1946–47) is a<br />

series of paintings in which<br />

Destruction of the Father<br />

Destruction of the Father (1974) is<br />

a biographical and a psychological<br />

exploration of the power<br />

dominance of father and his<br />

offspring. The piece is a flesh-toned<br />

installation in a soft and womb-like<br />

room. Made of plaster, latex, wood,<br />

fabric, and red light, Destruction of<br />

the Father was the first piece in<br />

which she used soft materials on a<br />

large scale. Upon entering the<br />

installation, the viewer stands in<br />

the aftermath of a crime. Set in a<br />

stylized dining room (with the dual<br />

impact of a bedroom), the abstract<br />

blob-like children of an overbearing<br />

father have rebelled, murdered,<br />

and eaten him.

telling the captive audience how<br />

great he is, all the wonderful<br />

things he did, all the bad people<br />

he put down today. But this goes<br />

on day after day. There is tragedy<br />

in the air. Once too often he has<br />

said his piece. He is unbearably<br />

dominating although probably he<br />

does not realize it himself.<br />

A kind of resentment grows and<br />

one day my brother and I decided,<br />

'the time has come!' We grabbed<br />

him, laid him on the table and<br />

with our knives dissected him. We<br />

took him apart and dismembered<br />

him, we cut off his penis. And he<br />

became food. We ate him up he<br />

was liquidated the same way he<br />

liquidated the children<br />

Exorcism in <strong>Art</strong><br />

In 1982, The Museum of Modern<br />

<strong>Art</strong> in New York City featured<br />

unknown artist,<br />

Louise Bourgeois's work. She was<br />

70 years old and a mixed media<br />

artist who worked on paper, with<br />

metal, marble and animal skeletal<br />

bones. Childhood family traumas<br />

"bred an exorcism in art" and she<br />

desperately attempted to purge<br />

her unrest with her work.<br />

She felt she could get in touch with<br />

issues of<br />

female identity, the body,<br />

the fractured family, long before<br />

the art world and society<br />

considered them expressed<br />

subjects in art. This was<br />

Bourgeous's way to find her center<br />

and stabilize her emotional unrest.<br />

The New York Times said at the<br />

time that "her work is charged with<br />

tenderness and violence,<br />

acceptance and defiance,<br />

ambivalence and conviction."<br />

Cells<br />

While in her eighties, Bourgeois<br />

produced two series of enclosed<br />

installation works she referred to as<br />

Cells. Many are small enclosures<br />

into which the viewer is prompted<br />

to peer inward at arrangements of<br />

symbolic objects; others are small<br />

rooms into which the viewer is<br />

invited to enter. In the cell pieces,<br />

Bourgeois uses earlier sculptural<br />

forms, found objects as well as<br />

personal items that carried strong<br />

personal emotional charge for the<br />

artist.

The cells enclose psychological<br />

and intellectual states, primarily<br />

feelings of fear and pain.<br />

Bourgeois stated that the Cells<br />

represent "different types of pain;<br />

physical, emotional and<br />

psychological, mental and<br />

intellectual ... Each<br />

Cell deals with a fear. Fear is pain ...<br />

Each Cell deals with the pleasure<br />

of the voyeur, the thrill of looking<br />

and being looked at."<br />

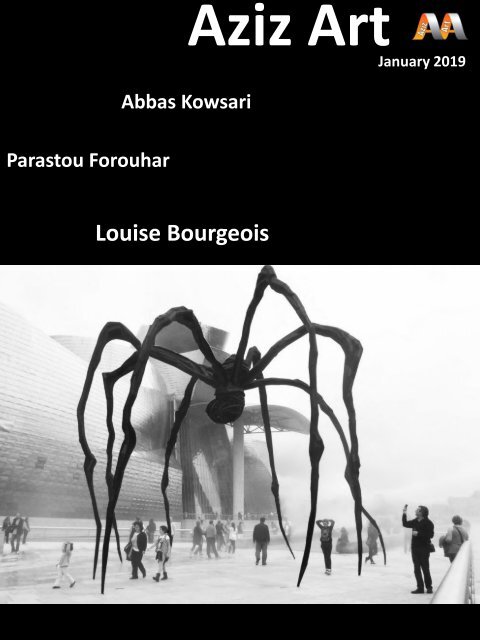

Maman<br />

Main article: Maman (sculpture)<br />

In the late 1990s, Bourgeois began<br />

using the spider as a central image<br />

in her art. Maman, which stands<br />

more than nine metres high, is a<br />

steel and marble sculpture from<br />

which an edition of six bronzes<br />

were subsequently cast. It first<br />

made an appearance as part of<br />

Bourgeois's commission for The<br />

Unilever Series for Tate Modern's<br />

Turbine Hall in 2000, and recently,<br />

the sculpture was installed at the<br />

Qatar National Convention Centre<br />

in Doha, Qatar.[35] Her largest<br />

spider sculpture titled Maman<br />

stands at over 30 feet (9.1 m) and<br />

has been installed in numerous<br />

locations around the world.It is<br />

the largest Spider sculpture ever<br />

made by Bourgeois. Moreover,<br />

Maman<br />

alludes to the strength of her<br />

mother, with metaphors of<br />

spinning, weaving, nurture and<br />

protection. The prevalence of the<br />

spider motif in her work has given<br />

rise to her nickname as<br />

Spiderwoman.<br />

The Spider is an ode to my mother.<br />

She was my best friend. Like a<br />

spider, my mother was a weaver.<br />

My family was in the business of<br />

tapestry restoration, and my<br />

mother was in charge of the<br />

workshop. Like spiders, my mother<br />

was very clever. Spiders are friendly<br />

presences that eat mosquitoes. We<br />

know that mosquitoes spread<br />

diseases and are therefore<br />

unwanted. So, spiders are helpful<br />

and protective, just like my mother.<br />

Maisons fragiles / Empty Houses<br />

Bourgeois's Maisons fragiles /<br />

Empty Houses sculptures are<br />

parallel, high metallic structures<br />

supporting a simple tray. One must<br />

see them in person to feel their<br />

impact. They are not threatening or<br />

protecting, but bring out the<br />

depths of anxiety within you.

Bachelard's findings from<br />

psychologists' tests show that an<br />

anxious child will draw a tall<br />

narrow house with no base.<br />

Bourgeois had a rocky/traumatic<br />

childhood and this could support<br />

the reason behind why these<br />

pieces were constructed.<br />

Printmaking<br />

Bourgeois's printmaking<br />

flourished during the early and<br />

late phases of her career: in the<br />

1930s and 1940s, when she first<br />

came to New York from Paris, and<br />

then again starting in the 1980s,<br />

when her work began to receive<br />

wide recognition. Early on, she<br />

made prints at home on a small<br />

press, or at the renowned<br />

workshop Atelier 17. That period<br />

was followed by a long hiatus, as<br />

Bourgeois turned her attention<br />

fully to sculpture. It was not until<br />

she was in her seventies that she<br />

began to make prints again,<br />

encouraged first by print<br />

publishers. She set up her old<br />

press, and added a second, while<br />

also working closely with printers<br />

who came to her house to<br />

collaborate. A very active phase of<br />

printmaking followed, lasting until<br />

the artist's death. Over the course<br />

of her life, Bourgeois created<br />

approximately 1,500 printed<br />

compositions.<br />

In 1990, Bourgeois decided to<br />

donate the complete archive of her<br />

printed work to The Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>. In 2013, The Museum<br />

launched the online catalogue<br />

raisonné, "Louise Bourgeois: The<br />

Complete Prints & Books." The site<br />

focuses on the artist's creative<br />

process and places Bourgeois's<br />

prints and illustrated books within<br />

the context of her overall<br />

production by including related<br />

works in other mediums that deal<br />

with the same themes and imagery.<br />

Pervasive themes<br />

One theme of Bourgeois's work is<br />

that of childhood trauma and<br />

hidden emotion. After Louise's<br />

mother became sick with influenza<br />

Louise's father began having affairs<br />

with other women, most notably<br />

with Sadie, Louise's English tutor.<br />

Louise was extremely watchful and<br />

aware of the situation. This was the<br />

beginning of the artist's<br />

engagement with double standards<br />

related to gender and sexuality,<br />

which was expressed in much of<br />

her work. She recalls her father<br />

saying

"I love you" repeatedly to her<br />

mother, despite infidelity.<br />

"He was the wolf, and she was the<br />

rational hare, forgiving and<br />

accepting him as he was.<br />

"Her 1993 work "Cell: You Better<br />

Grow Up", part of her "Cell"<br />

series, speaks directly to Louise's<br />

childhood trauma and the<br />

insecurity that surrounded her.<br />

2002's "Give or Take" is defined by<br />

hidden emotion, representing the<br />

intense dilemma that people face<br />

throughout their lives as they<br />

attempt to balance the actions of<br />

giving and taking. This dilemma is<br />

not only represented by the shape<br />

of the sculpture, but also the<br />

heaviness of the material this<br />

piece is made of.<br />

Architecture and memory are<br />

important components of<br />

Bourgeois's work. In numerous<br />

interviews, Louise describes<br />

architecture as a visual expression<br />

of memory, or memory as a type<br />

of architecture. The memory<br />

which is featured in much of her<br />

work is an invented memory -<br />

about the death or exorcism of<br />

her father. The imagined memory is<br />

interwoven with her real memories<br />

including living across from a<br />

slaughterhouse and her father's<br />

affair. To Louise her father<br />

represented injury and war,<br />

aggrandizement of himself and<br />

belittlement of others and most<br />

importantly a man who<br />

represented betrayal. Her 1993<br />

work "Cell (Three White Marble<br />

Spheres)" speaks to fear and<br />

captivity. The mirrors within the<br />

present an altered and distorted<br />

reality.<br />

Sexuality is undoubtedly one of the<br />

most important themes in the work<br />

of Louise Bourgeois. The link<br />

between sexuality and fragility or<br />

insecurity is also powerful. It has<br />

been argued that this stems from<br />

her childhood memories and her<br />

father's affairs. 1952's "Spiral<br />

Woman" combines Louise's focus<br />

on female sexuality and torture.<br />

The flexing leg and arm muscles<br />

indicate that the Spiral Woman is<br />

still above though she is being<br />

suffocated and hung. 1995's "In<br />

and Out" uses cold metal materials<br />

to link sexuality with anger and<br />

perhaps even captivity.

The spiral in her work demonstrates the dangerous search for<br />

precarious equilibrium, accident-free permanent change, disarray,<br />

vertigo, whirlwind. There lies the simultaneously positive and negative,<br />

both future and past, breakup and return, hope and vanity, plan and<br />

memory.<br />

Louise Bourgeois's work is powered by confessions, self-portraits,<br />

memories, fantasies of a restless being who is seeking through her<br />

sculpture a peace and an order which were missing throughout her<br />

childhood.

Parastou Forouhar born 1962 in<br />

Tehran is an Iranian installation<br />

artist who lives and works out of<br />

Frankfurt, Germany. Forouhar’s<br />

art reflects her criticism of the<br />

Iranian government and often<br />

plays with the ideas of identity.<br />

Her artwork expresses a critical<br />

response towards the politics in<br />

Iran and Islamic Fundamentalism.<br />

The loss of her parents fuels<br />

Forouhar’s work and challenges<br />

viewers to take a stand on war<br />

crimes against innocent citizens.<br />

Forouhar's work has been<br />

exhibited around the world<br />

including Iran, Germany, Russia,<br />

Turkey, England, United States and<br />

more.<br />

Early life and education<br />

The daughter of political activist<br />

Parvaneh Forouhar and politician<br />

Dariush Forouhar, Parastou was<br />

born in 1962 in Tehran, Iran. Her<br />

father critiqued the Iranian<br />

government and he founded and<br />

led the Hezb-e-Mellat-e Iran<br />

(Nation Party of Iran), which was<br />

a pan-Iranist opposition party in<br />

Iran.<br />

Her parents were stabbed in their<br />

home in the November of 1998,<br />

and Parastou relocated to Germany<br />

in 1991, where she has continued<br />

her work.She lives in exile because<br />

she is considered a political threat<br />

by the Iranian government.After<br />

her parents' death, Parastou<br />

channeled her grief into her art, her<br />

art explores topics from democracy<br />

to woman's rights to her parents'<br />

murder.Parastou studied <strong>Art</strong> at the<br />

University of Tehran from 1984<br />

until 1990, where she earned her<br />

B.A., she then continued to study at<br />

the Hochschule für Gestaltung in<br />

Offenbach am Main in Germany<br />

and went on to earn her M.A. in<br />

1994.Parastou lives with her two<br />

children in Frankfurt Germany now.<br />

Work<br />

Forouhar's work is autobiographical<br />

in nature and responds to the<br />

politics that have shaped and<br />

defined contemporary Iranian<br />

citizenship both in Iran and<br />

abroad.She works within a range of<br />

media including site specific<br />

installation, animation, digital<br />

drawing, photography, signs and<br />

products. Through her work<br />

16

she processes very real<br />

experiences of loss, pain, and<br />

state-sanctioned violence through<br />

animations, wallpapers, flipbooks,<br />

and drawings.Forouhar uses<br />

culturally specific motifs found<br />

within traditional Iranian arts such<br />

as Islamic calligraphy and Persian<br />

miniature painting to question<br />

the ways these forms can<br />

generate a lack of individual<br />

agency while adhering to a<br />

standardized understanding of<br />

beauty and cultural identity<br />

Forouhar's work is a<br />

utobiographical in nature and<br />

responds to the politics that have<br />

shaped and defined contemporary<br />

Iranian citizenship both in Iran<br />

and abroad. She works within a<br />

range<br />

of media including site specific<br />

installation, animation, digital<br />

drawing, photography, signs and<br />

products. Through her work, she<br />

processes very real experiences of<br />

loss, pain, and state-sanctioned<br />

violence through animations,<br />

wallpapers, flipbooks, and<br />

drawings. Forouhar uses<br />

culturally specific motifs found<br />

within traditional Iranian arts such<br />

as Islamic calligraphy and Persian<br />

miniature painting to question the<br />

ways these forms can generate a<br />

lack of individual agency while<br />

adhering to a standardized<br />

understanding of beauty and<br />

cultural identity.<br />

In 2012 she received the Sophie<br />

von La Roche Award in recognition<br />

for her work that confronts issues<br />

concerning displacement, gender<br />

and cultural identity.<br />

Solo exhibitions of Forouhar's work<br />

have been held at Stavanger<br />

Cultural Center, Norway; Golestan<br />

<strong>Art</strong> Gallery, Tehran; Hamburger<br />

Bahnhof - Museum fur Gegenwart,<br />

Berlin; City Museum, Crailsheim,<br />

Germany; and German Cathedral,<br />

Berlin.She has participated in group<br />

exhibitions at Schim Kunsthalle,<br />

Frankfurt; Frauenmuseum Bonn;<br />

Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Frankfurt;<br />

Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum,<br />

Joanneum, Graz,<br />

Austria; House of World Cultures,<br />

Berlin; Deutsches Hygiene-<br />

Museum, Dresden; Jewish Museum<br />

of Australia, Melbourne; and Jewish<br />

Museum San Francisco.

Her work can be found in the<br />

following permanent collections:<br />

The Queensland <strong>Art</strong> Museum,<br />

Queensland; Belvedere, Vienna;<br />

Badisches Landesmuseum,<br />

Karlsruhe; Museum of<br />

Modern <strong>Art</strong>, Frankfurt; and the<br />

Deutsche Bank <strong>Art</strong> Collection.<br />

In 2002, the Iranian Cultural<br />

Ministry censored Forouhar's<br />

photo exhibition, Blind Spot, a<br />

collection of images depicting a<br />

veiled, gender-neutral figure<br />

with a bulbous, featureless face.<br />

Forouhar chose to exhibit the<br />

empty frames on the wall on<br />

opening night instead of forgoing<br />

the show.<br />

Forouhar and her brother got<br />

involved in activism after their<br />

parents got brutally murdered and<br />

they weren't allowed to publicly<br />

mourn or speak out about their<br />

deaths. Her artwork critiques the<br />

Iranian government and focuses on<br />

examining her identity and culture.<br />

Forouhar has been featured in<br />

several art fairs including the<br />

Brodsky Center Fair, at Rutgers<br />

University in 2015, and Pi <strong>Art</strong>works<br />

fair Istanbul/London, in 2016 and<br />

2017 (she was at both locations: in<br />

Contemporary Istanbul and<br />

London)

Abbas Kowsari was born in 1970, in Iran. He graduated in 1988 with a<br />

diploma from Shariati High School in Tehran, where he continues to live<br />

and work.<br />

Kowsari has worked for over ten leading Iranian newspapers, most of<br />

them now banned from publishing. He currently works as the senior<br />

photo editor for E’temad newspaper in Tehran.<br />

His photos have been published in Paris Match, Der Spiegel and Colors<br />

magazine of Benetton, along with several other international<br />

publications.<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

2006-present Photo Editor E’temad Newspaper<br />

2007-present Photo Editor Sarmayeh Economics Newspaper<br />

2003-present Photo Editor Haft Monthly <strong>Art</strong>s Magazine –Closed Down<br />

Exhibitions<br />

2008 Shade of Water – Shade of Earth, Aaran <strong>Art</strong> Gallery Tehran<br />

2004 Muslims Muslims, La Vilette Paris<br />

2003 Portraits, French Embassy Damascus<br />

2002 Iran Contemporary Photographers, Assar <strong>Art</strong> Gallery Tehran<br />

21

http://www.aziz-anzabi.com