The Grand Painting Exhibition with a Pile of Paintings

The catalogue contains a text by Branislav Dimitrijević, as well as reproductions and info on all the works.

The catalogue contains a text by Branislav Dimitrijević, as well as reproductions and info on all the works.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Album i jedna kesica (7 slicica)<br />

200 dinara<br />

Jedna kesica<br />

(7 slicica)<br />

50 dinara<br />

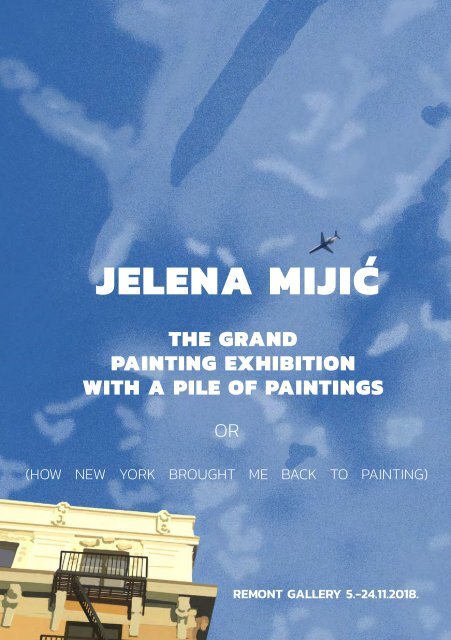

JELENA MIJIĆ<br />

Ko popuni album može da dobije nagrade<br />

THE GRAND<br />

I<br />

nagrada<br />

PAINTING EXHIBITION<br />

Slika iz albuma po izboru dobitnika<br />

WITH A PILE OF PAINTINGS<br />

OR<br />

II<br />

nagrada<br />

Specijalni paket iz Njujorka<br />

(HOW NEW YORK BROUGHT ME BACK TO PAINTING)<br />

III<br />

nagrada<br />

Potpisan katalog 57. Oktobarskog salona<br />

REMONT GALLERY 5.-24.11.2018.

On the occasion <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Grand</strong> painting exhibition<br />

<strong>of</strong> Jelena Mijić, <strong>with</strong> a pile <strong>of</strong> paintings<br />

A city is text. Every text survives thanks to repetition<br />

<strong>of</strong> stereotypes and their breaking, to trivialities<br />

and their avoiding. By writing a short footnote to<br />

this city, I’m just stamping the words spoken countless<br />

times. Of course, it’s not me that is important,<br />

it’s the footnote.<br />

(Dubravka Ugrešić, Fox)<br />

““Really,” – Dubravka Ugrešić wonders at the beginning <strong>of</strong> her latest novel<br />

Fox – “How are stories conceived?” Many writers would welcome such<br />

a question as a cue for a diatribe <strong>of</strong> their unfathomable creative endeavour,<br />

and for that reason people respect such writers. But some others,<br />

Ugrešić writes, “prefer to shrug their shoulders and allow the readers to<br />

believe that stories grow like weed...” When it comes to exhibitions <strong>of</strong><br />

paintings, such an assumption is quite conventional – exhibitions exist<br />

because paintings are, simply, already there, they have somehow grown,<br />

sprung up. After all, one assumes that the production precedes the consumption,<br />

that <strong>with</strong>out the production <strong>of</strong> art, there is no consumption,<br />

for <strong>with</strong>out art production, you are the roots <strong>with</strong>out a gourd, you are<br />

the meme <strong>of</strong> a conceptual artist whom a famous comic hero slaps, trying<br />

to get through her head that she is conceptual precisely because she can<br />

neither draw nor paint. But the exhibition in front <strong>of</strong> us is turning things<br />

and claims that the only way to be “conceptual” in art today is to draw and<br />

paint many pictures, piles and heaps <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

<strong>The</strong> grand painting exhibition <strong>with</strong> a pile <strong>of</strong> paintings, inasmuch as every<br />

artistic act along the line <strong>of</strong> administrative conceptualism, was conceived

on the basis <strong>of</strong> the confrontation <strong>of</strong> several artistic assumptions and propositions<br />

<strong>with</strong> actual conditions and circumstances <strong>of</strong> production and distribution.<br />

First and foremost, the artist was under institutional-pr<strong>of</strong>essional-moral<br />

obligation to prepare an exhibition at Belgrade’s Remont<br />

Gallery because this was expected in the competition regulations for the<br />

Mangelos Prize she received a year ago and thanks to which she went to a<br />

residency in New York City, USA. Like every dedicated artist, art lover, curator,<br />

art historian or someone <strong>of</strong> that sort, Jelena Mijić (hereinafter “Jela”<br />

or “the artist”) had spent most <strong>of</strong> her time in NY visiting exhibitions, galleries,<br />

museums; walking the streets; riding on subway; attending openings<br />

<strong>of</strong> exhibitions in the galleries she visited, drinking white wines and<br />

standing <strong>with</strong> the glass in front <strong>of</strong> the works whilst chatting about art<br />

<strong>with</strong> many, mostly friendly persons she encountered. Whilst engaged in<br />

these activities, she finally realized that in most <strong>of</strong> these galleries and museums,<br />

she was mostly attending and observing exhibitions <strong>of</strong> paintings.<br />

And so, empirically again, she concluded that it seemed, now and after<br />

all, that the current present <strong>of</strong> art, <strong>of</strong> contemporary art, had somehow<br />

turned out to be – painterly.<br />

After Jela’s return to Belgrade, everything turned out to be quite logical.<br />

<strong>The</strong> exhibition needed to be organised, if for no other reason, then because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the responsibility to the expectations <strong>of</strong> the jury that had had<br />

the confidence to award a young painter, although she, by her own admission,<br />

had not painted since the third year <strong>of</strong> her studies at the art<br />

academy. Jela was awarded for her “conceptual” works, although they,<br />

too, were mostly paintings <strong>of</strong> sorts– yet not to the full extent to which this<br />

“real paintings” exhibition which is now in front <strong>of</strong> us. <strong>The</strong> citation for<br />

the award was the following: “Jelena Mijić was awarded for a work that<br />

demonstrates an open and experimental approach to researching and<br />

understanding the complex relationships on which art production and<br />

its social perception are based.” In New York, this largest centre <strong>of</strong> the<br />

decentralized world, it turned out that art production implies primarily<br />

the production <strong>of</strong> paintings, because this is simply “good for the economy”:<br />

paints, canvases, brushes are produced and spent, more and more <strong>of</strong><br />

them, better and better, and the social perception <strong>of</strong> this production goes<br />

on <strong>with</strong> the help <strong>of</strong> a glass <strong>of</strong> wine and canapés, also produced <strong>with</strong> the

help <strong>of</strong> those perform temporary and occasional jobs. And, in the end,<br />

there is something to sell and buy. Win-win art.<br />

So, the artist really took this lesson seriously and fell to work vigorously.<br />

She took the money received <strong>with</strong> the prize and, like a “true painter”,<br />

bought various paints: high-quality acrylics, oils – mostly Daler-Rowney,<br />

<strong>of</strong> which she mainly used raw and baked umbra (for she studied at the<br />

Belgrade Academy, after all), but also Naples yellow, titanium white,<br />

many different blues, but most <strong>of</strong>ten blue-gray (the favourite colour <strong>of</strong><br />

the author <strong>of</strong> these lines, which attracted him to these paintings), and<br />

she also used oil paint in Winsor & Newton sticks and acrylic in Liquitex<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essional spray. She bought, <strong>of</strong> course, all kinds <strong>of</strong> brushes <strong>of</strong> various<br />

manufacturers. She bought canvases – fortunately the smaller ones already<br />

stretched – and, in a little less than a month, she painted 33 paintings,<br />

at least so far. She first claimed that she had painted 35 <strong>of</strong> them, and<br />

we don’t know what has happened <strong>with</strong> the missing two, although the<br />

artist says she has simply counted them incorrectly.<br />

<strong>The</strong> organization <strong>of</strong> the production process looked roughly like this: first,<br />

<strong>with</strong>out even knowing that some real paintings would arise from it, she<br />

took photographs <strong>of</strong> the city she was visiting – a view <strong>of</strong> the Brooklyn<br />

Bridge, a view from below at high buildings, a view from above from high<br />

buildings, a glimpse through a wired fence <strong>of</strong> something that is enclosed<br />

by the wire fence, a portrait <strong>of</strong> an unknown girl on a subway train, and<br />

afterwards <strong>of</strong> some other people on the subway, a self-portrait <strong>with</strong> a facial<br />

cosmetic mask, white clouds and a beach on Coney Island, a fairly<br />

smashed car, a detail on the facade <strong>of</strong> a building, a detail <strong>of</strong> the canopy<br />

<strong>of</strong> a ginkgo tree, then one serious gallery-talk, an umbrella that flew into<br />

the wind, some luggage unloaded on the street, a selfie in the mirror, and<br />

again some paintings in a gallery, and some more paintings in a gallery,<br />

and a man in a gallery watching the paintings, and many other things<br />

that could be expected as a nice remembrance <strong>of</strong> a journey like this.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se photographs have thus become mechanically produced raw materials,<br />

and then came processing <strong>of</strong> this raw material by means <strong>of</strong> technical-manual<br />

processing, i.e., <strong>with</strong> the help <strong>of</strong> a computer programme<br />

designed for this kind <strong>of</strong> image manipulation. This kind <strong>of</strong> processing

activity resulted in the sketches for paintings. And the paintings, that final<br />

product, really are paintings, the “real” ones, hand-painted in a room<br />

in her flat, adapted for that purpose. For a painter who had not painted<br />

since the third year <strong>of</strong> her studies, and I hope that local art critics would<br />

agree, these are rather good paintings! Moreover, it seems that the fact<br />

that the artist had not been engaged in painting, and that she forgot a<br />

little <strong>of</strong> what she had been taught about the way to do it, only improved<br />

her painterly métier.<br />

In the end, let’s try to sum up. Although much could already be learned<br />

about this in the past hundred years, artists, here and now, in their works<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten still choose either expression or symbolization and, unfortunately,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten both at the same time: the first through the second or the<br />

second through the first. And in both keys, Jela’s paintings are, simply, inadequate.<br />

In contrast, what is common to both Jela’s “conceptual” works<br />

and now these “real” paintings is, above all, the formalization process.<br />

Why and under what circumstances does an artistic process acquire a<br />

certain form defined by the production conditions, circumstances and<br />

requirements? How does an image translate from its technical into its<br />

manual form? What is gained and what is lost in this translation? How do<br />

some filled cracks in the asphalt, or shadows that some other exhibited<br />

paintings make on the gallery walls – that is, everything that is found in<br />

a photograph by its unavoidable presence – how does it then turn into a<br />

painting stroke by this simple translation in which the surplus is not left<br />

out but transformed into some kind <strong>of</strong> painterly noise, materialized by<br />

a brush stroke, first the computer brush, and then the “real” one? Thus,<br />

these images are at the same time analyses <strong>of</strong> an operational procedure in<br />

the production <strong>of</strong> painting, and an iconological analysis <strong>of</strong> the material<br />

traces that are transformed from one type <strong>of</strong> image into another, from<br />

one reproduction <strong>of</strong> the scene into a reproduction <strong>of</strong> the reproduction <strong>of</strong><br />

the same scene. In this way, painting, as a production process, is always<br />

and at the same time both a practical and contemplative activity, that is,<br />

a practical contemplation <strong>of</strong> the relationship between the seen and the<br />

constructed. <strong>The</strong> active and the contemplative, as the iconologist Erwin<br />

Pan<strong>of</strong>sky once concluded, jointly “interpenetrate” in what we understand<br />

and construct as reality: “<strong>The</strong> man who is run over by an automobile is

un over by mathematics, physics and chemistry. For he who leads the<br />

contemplative life cannot help influencing the active, just as he cannot<br />

prevent the active life from influencing his thought.” <strong>Painting</strong> therefore<br />

does not have to be an obstacle to art-thinking.<br />

Branislav Dimitrijević

<strong>Painting</strong> is like travelling, you have the<br />

time to really think about everything<br />

acryllic on Ikea blind “Tupplur”<br />

180x135 cm<br />

Squares<br />

acryllic on Ikea blind “Tupplur”<br />

two-sided painting<br />

100x130 cm<br />

Water<br />

acryllic on Ikea blind “Tupplur”<br />

two-sided painting<br />

100x130 cm<br />

On the road to MOMA<br />

oil on canvas<br />

80x100 cm<br />

Fallen gingko leaves in front <strong>of</strong> the<br />

second appartment we lived in<br />

oil and acryllic on canvas<br />

80x100 cm

Broken umbrella, on the way to the Queens<br />

museum, my favorite museum in NYC.<br />

oil on canvas<br />

60x70 cm<br />

Metro station abstraction<br />

oil on canvas<br />

60x70 cm<br />

A guard is eating an apple at an opening <strong>of</strong><br />

a Richard Serra exhibition in a fancy gallery<br />

in Chelsea<br />

oil on canvas<br />

70x60 cm<br />

Central park view from the terrace <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Metropolitan Museum<br />

oil on canvas<br />

60x50 cm<br />

Coney Island<br />

oil and acryllic on canvas<br />

50x60 cm<br />

October 16th<br />

oil on canvas<br />

50x60 cm

A sports court abstraction<br />

oil on canvas<br />

50x60 cm<br />

Carton twin towers<br />

oil on canvas<br />

50x60 cm<br />

Street scene on Manhattan<br />

oil on canvas<br />

50x60 cm<br />

Luka on Broadway station looking at a<br />

polaroid he just made<br />

oil on canvas<br />

40x50 cm<br />

A visitor at an opening in Chelsea<br />

oil on canvas<br />

40x50 cm

Antique sculpture at the Metropoliten Museum<br />

oil on canvas<br />

40x50 cm<br />

Luka at MOMA PS1<br />

oil on canvas<br />

40x50 cm<br />

At the Laura Owens exhibition in Whitney<br />

Museum<br />

oil on canvas<br />

40x50 cm<br />

Accident on Broadway<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm<br />

Artist Linnea Vedder at the opening <strong>of</strong> her<br />

exhibition at the Lubov gallery in Chinatown<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm

<strong>The</strong> second day<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm<br />

A little drink at an exhibition opening in the<br />

Lower East Side<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm<br />

Manhattan<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm<br />

A view from the platform at the first floor <strong>of</strong><br />

MOMA at the exhibiton <strong>of</strong> Louise Bourgeois<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm<br />

Selfportrait <strong>with</strong> a face-mask that was being<br />

handed out on the street in Chinatown<br />

oil on canvas<br />

25x35 cm

A break<br />

oil and acryllic on canvas<br />

10x15 cm<br />

October 18th<br />

oil and acryllic on canvas<br />

10x15 cm<br />

Taking a photo <strong>of</strong> the Statue <strong>of</strong> liberty<br />

during the golden hour<br />

acryllic on canvas<br />

10x15 cm<br />

Sky over Brooklyn<br />

oil and acryllic on canvas<br />

10x15 cm<br />

When I think about New York, I think about<br />

the people on the subway<br />

acryllic on canvas<br />

10x15 cm

nyc2017bgd2018