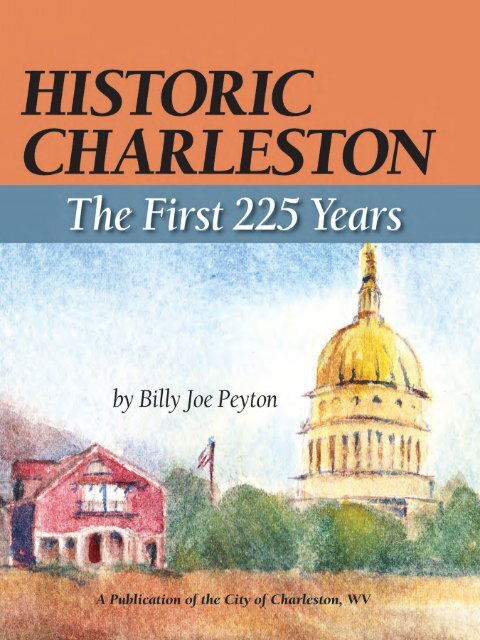

Historic Charleston: The First 225 Years

An illustrated history of Charleston, West Virginia, paired with the histories of local companies and organizations that made the city great.

An illustrated history of Charleston, West Virginia, paired with the histories of local companies and organizations that made the city great.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Thank you for your interest in this HPNbooks publication. For more information about other<br />

HPNbooks publications, or information about producing your own book with us, please visit www.hpnbooks.com.

HISTORIC CHARLESTON<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>First</strong> <strong>225</strong> <strong>Years</strong><br />

by Billy Joe Peyton<br />

A publication of the City of <strong>Charleston</strong><br />

HPNbooks<br />

A division of Lammert Incorporated<br />

San Antonio, Texas

CONTENTS<br />

✧<br />

This c. 1850 single-span stone arch<br />

bridge carried the Point Pleasant Road<br />

over Kanawha Two Mile Creek at the<br />

Littlepage Farm. It still stands but was<br />

bypassed long ago.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF THE HISTORIC<br />

GLENWOOD FOUNDATION.<br />

3 WELCOME FROM MAYOR DANNY JONES<br />

4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

5 CHAPTER 1 Prehistory and Early Settlement: to 1820<br />

17 CHAPTER 2 Town at the Mouth of Elk: 1820-1860<br />

31 CHAPTER 3 Civil War and Aftermath: 1860-1870<br />

49 CHAPTER 4 An Emerging Capital City: 1870-1900<br />

61 CHAPTER 5 Industrial Expansion and Growth: 1900-1970<br />

89 CHAPTER 6 Epilogue—A City in Transition: 1970-present<br />

102 BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

103 SHARING THE HERITAGE<br />

151 SPONSORS<br />

152 ABOUT THE AUTHOR<br />

<strong>First</strong> Edition<br />

Copyright © 2013 HPNbooks<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing<br />

from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to HPNbooks, 11535 Galm Road, Suite 101, San Antonio, Texas, 78254. Phone (800) 749-9790, www.hpnbooks.com.<br />

ISBN: 978-1-939300-19-5<br />

Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 2013952553<br />

<strong>Historic</strong> <strong>Charleston</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>First</strong> <strong>225</strong> <strong>Years</strong><br />

author: Billy Joe Peyton<br />

contributing writer for “Sharing the Heritage”: Joe Goodpasture<br />

HPNbooks<br />

president: Ron Lammert<br />

project manager: Bob Sadoski<br />

administration: Donna M. Mata, Melissa G. Quinn<br />

book sales: Dee Steidle<br />

production: Colin Hart, Evelyn Hart, Glenda Tarazon Krouse, Tony Quinn<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

2

WELCOME FROM MAYOR DANNY JONES<br />

WELCOME FROM MAYOR DANNY JONES<br />

I am blessed to be the mayor of my home town, the city where I grew up and learned so much<br />

about life, and I am pleased to greet you as you begin exploring the history of <strong>Charleston</strong> in the<br />

pages of this book. As you can see, <strong>Charleston</strong> has a very rich history over <strong>225</strong> years and counting.<br />

While neither you nor I can change anything that is part of our past, we can—and should—learn<br />

from it as we prepare for the future. As a student of history, I am fascinated to be able to look<br />

back and learn how situations developed, how people made decisions that shaped events and<br />

how people and events created the path to where we are now as a world, nation and city.<br />

We need to know where we have been to understand fully the direction in which we are heading.<br />

Our recent history has produced some exciting developments in <strong>Charleston</strong> that make me<br />

very hopeful about our future. Over the past decade, we have witnessed many new events<br />

and investments in <strong>Charleston</strong> that make our capital city a much more attractive place for people<br />

to live, visit and invest:<br />

• <strong>The</strong> opening of the Clay Center for the Arts and Sciences as a world class performance hall<br />

and activity center for people of all ages and interests;<br />

• Creation of FestivALL <strong>Charleston</strong>, which has become a ten-day celebration of art and culture<br />

and has led to the empowerment of our city’s artistic community throughout the year;<br />

• Development of Appalachian Power Park, which preserved professional baseball in our city<br />

as the home of the West Virginia Power and dozens of other community events every year;<br />

• Renovation of Haddad Riverfront Park with the new retractable canopy that makes events there<br />

more inviting and the addition of the Schoenbaum Stage that pays tribute to our sternwheeling<br />

history while hosting weekly free concerts Live on the Levee during the summer months;<br />

• Growth and expansion of the University of <strong>Charleston</strong> with seven new buildings on campus<br />

(including a new School of Pharmacy) and new investment both downtown (Graduate School<br />

of Business) and at Laidley Field (University of <strong>Charleston</strong> stadium);<br />

• Transformation of affordable housing in the city of <strong>Charleston</strong> from the former Spring Hill<br />

complex and Washington Manor to Orchard Manor, Littlepage Terrace and beyond, so that<br />

people in need have cleaner, safer and better places to call home;<br />

• Expansion of neighborhood organizations in four different parts of the city, including<br />

new Main Street organizations on both the East End and West Side, that have mobilized<br />

personal and financial investment in places throughout the city and encouraged people to<br />

follow their passions for projects that make for more business-friendly and neighbor-friendly<br />

neighborhoods; and<br />

• A plan for renovating the <strong>Charleston</strong> Civic Center to make it more inviting and user-friendly<br />

for the groups, events and visitors that hold the greatest promise for infusing new money into<br />

the local economy.<br />

Honestly, I could fill pages with other projects, special events and investments that people and<br />

businesses have made in our city in recent years. But for now, I invite you to explore <strong>Charleston</strong>’s<br />

history through this book as we look both back to the past and ahead to bright future.<br />

✧<br />

Mayor Danny Jones.<br />

W E L C O M E F R O M M A Y O R D A N N Y J O N E S<br />

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

This work was carried out in cooperation with the <strong>Charleston</strong> <strong>Historic</strong> Landmarks<br />

Commission, to commemorate the founding of Fort Lee <strong>225</strong> years ago and the “town at mouth<br />

of Elk” six years later, as well as the West Virginia sesquicentennial. Many people have provided<br />

generous support and assistance on the project, especially the cheerful staff at the West Virginia<br />

State Archives; special recognition goes to Jerry Waters, who maintains a popular website<br />

brimming with rare and historic images of <strong>Charleston</strong> at www.mywvhome.com. Heartfelt thanks<br />

to the City of <strong>Charleston</strong> for showing confidence in me throughout the process, to <strong>Charleston</strong><br />

City Manager David Molgaard for his editorial assistance, and to Ron Lammert and the fine<br />

folks at <strong>Historic</strong>al Publishing Network for sticking with me as I completed the long-awaited<br />

manuscript. Your support is greatly appreciated.<br />

Finally, I dedicate this project to my amazingly talented wife, CJ, and our two children whom<br />

I love dearly. Cindie and Kendy, it is my sincere hope that you both grow to appreciate the rich<br />

history of <strong>Charleston</strong> as much as I do.<br />

Billy Joe Peyton<br />

June 2013<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

4

C H A P T E R 1<br />

PREHISTORY AND<br />

EARLY SETTLEMENT: TO 1820<br />

Long before Europeans arrived, Native Americans knew about the area at the mouth of<br />

Elk River, a stream the Shawnee termed Tis-kel-wah, meaning “river of fat elk,” while the<br />

Delawares are said to have called it Pe-quo-ni, meaning “the walnut river.” It is unclear how the<br />

Kanawha River got its name. Some sources attribute it to the white explorers who named it after<br />

the Indians who lived along the river. Another possibility is that it was named after the island<br />

where the Piscataway Indians lived, “Conoy,” which may be a shortened form of “Kanawha,”<br />

pronounced as “Kanaw.” <strong>The</strong>re are also stories that the river was given its name by Native<br />

Americans as “Kanawah,” which meant “place of the white stones.” Apparently, the Shawnee<br />

people called the river ”Keninskeha,” which meant “river of evil spirits.” <strong>The</strong>re is some<br />

uncertainty about this story, as both names describe the New River more than the Kanawha.<br />

In fact, during colonial times, the New and Kanawha Rivers were considered to be the same<br />

waterway, and even sometimes called “Woods” River for Abraham Wood, who was responsible<br />

for early seventeenth century explorations of West Virginia. In 1671, Wood, along with a group<br />

that included Thomas Batts and Robert Fallam, discovered the river now called the New.<br />

✧<br />

Used to define the boundaries of the<br />

newly independent United States,<br />

the 1755 John Mitchell map is the most<br />

comprehensive map of eastern North<br />

America during the colonial era.<br />

WIKIPEDIA COMMONS, FROM LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.<br />

HTTP://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:MITCHELL_<br />

MAP-06FULL2_COMPRESSED.JPG<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

5

✧<br />

In 1755, Shawnee captive Mary Ingles<br />

became the first documented non-Native<br />

American to make salt in the<br />

Kanawha Valley.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

6<br />

Whatever name aboriginal people gave to<br />

the local waterway, they called the Kanawha<br />

Valley home for centuries before the first<br />

Europeans arrived. <strong>The</strong> area’s recorded history<br />

is less than two-and-a-half centuries old,<br />

but archaeological evidence reveals human<br />

habitation for 12,000 years before that. Native<br />

American occupation evolved through three<br />

progressive stages, from the Paleo-Indian to<br />

Archaic and Woodland cultures. Physical<br />

evidence of each culture has been discovered<br />

in the valley, but the most visible reminders<br />

are the burial mounds left by the Woodland<br />

peoples. In 1881 the Smithsonian Institution<br />

conducted archeological excavations relating<br />

to these prehistoric mound builders. By 1890<br />

about 100 mounds and earthworks had<br />

been identified in the Kanawha Valley, and<br />

among them was the Criel Mound in South<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong>, the second-largest burial mound<br />

in West Virginia.<br />

By the time European settlers crossed the<br />

Appalachian Mountains, virtually all Native<br />

American villages had been abandoned and<br />

the Kanawha and Elk valleys were used<br />

primarily as a hunting ground by the<br />

Shawnee, Cherokee, and Iroquois tribes. At<br />

the mouth of Campbell’s Creek, about five<br />

miles above Elk River, were salt springs that<br />

became known as the Great Buffalo Lick, or<br />

Kanawha Licks, that attracted buffalo, deer,<br />

and other game. Parties of Indians often came<br />

to hunt the abundant game and boil the brine<br />

to make salt, which was used for seasoning<br />

and food preservation.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first Europeans known to have viewed<br />

the future site of <strong>Charleston</strong> were Shawnee<br />

captives taken from their home at Draper’s<br />

Meadows (near present-day Blacksburg,<br />

Virginia) in July of 1755. Among them was<br />

twenty-four-year-old Mary Draper Ingles and<br />

her two young sons, aged four and two. <strong>The</strong><br />

group traveled on foot to Paint Creek, which<br />

they followed to its mouth on Kanawha River<br />

about twenty-two miles above <strong>Charleston</strong>. At<br />

the Kanawha Licks the party paused to make<br />

salt, which they took back to their Shawnee<br />

village near Chillicothe, Ohio. Mary Ingles’<br />

remarkable story ended with her daring escape<br />

and an epic 40-day, 400-mile trek in which

she followed the Ohio, Kanawha and New<br />

rivers back home. Although her trials ended<br />

in a joyous family reunion, Mary and William<br />

Ingles lost one son who probably died in<br />

captivity, while another son was adopted into<br />

a Shawnee family and did not see his<br />

biological parents for many years.<br />

Efforts to settle the trans-montane region of<br />

Virginia met with little success prior to the<br />

French and Indian War. Although optimism<br />

reigned after the British victory over France in<br />

1763, it did not immediately open the Kanawha<br />

Valley to permanent settlement. Shawnee Chief<br />

Cornstalk led bloody raids on the Greenbrier<br />

settlements shortly thereafter, which adversely<br />

impacted attempts to populate the region. In<br />

an effort to placate Native American claims<br />

and dissuade frontier violence, King George III<br />

issued a royal proclamation that prohibited<br />

settlement beyond the crest of the Alleghenies<br />

by declaring the area as an Indian Reserve.<br />

Persistent Cherokee and Iroquois claims in<br />

present-day West Virginia were permanently<br />

extinguished with the treaties of Hard Labor<br />

and Fort Stanwix in 1768, followed by<br />

the Treaty of Lochaber in 1770, but strong<br />

Shawnee claims remained unresolved and<br />

contributed to persistent attacks originating<br />

from Ohio.<br />

In 1770 speculators began claiming<br />

Kanawha lands. Among them was George<br />

Washington, who personally selected 23,000<br />

acres bordering Kanawha River and extending<br />

more than forty miles above its mouth. <strong>The</strong><br />

first residents ventured into the area in 1771,<br />

when Simon Kenton, George Strader and<br />

John Yeager built a cabin along Elk River<br />

about two miles above <strong>Charleston</strong> which they<br />

used as a base camp for hunting and trapping.<br />

Considered the first Europeans to actually live<br />

in the Kanawha Valley, the trio remained until<br />

March of 1773 when an Indian raiding party<br />

attacked them at camp. Yeager died in the<br />

ambush, while Kenton and Strader escaped<br />

on foot to Point Pleasant and did not return.<br />

Also in 1773, Walter Kelly established a<br />

settlement along Kelly’s Creek at present-day<br />

Cedar Grove, about twenty miles above<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong>. Settlers in his group assumed<br />

considerable risk because they had ventured<br />

far beyond the protection of volunteer militia<br />

units that guarded the Greenbrier settlements<br />

eighty miles to the east. In the spring and<br />

summer of that year, Shawnees launched raids<br />

from Ohio into West Virginia, prompting<br />

Kelly to send his family back to the safety of<br />

the Greenbrier settlements before being killed<br />

himself. In 1774, William Morris assumed<br />

Kelly’s claim. One of Morris’s sons settled on<br />

Lens Creek (Marmet), and another moved<br />

down the south side of Kanawha River<br />

opposite Campbell’s Creek. Within a short<br />

time, additional settlements had sprung up<br />

at Pratt, Hugheston, and Shrewsbury, while<br />

separate expeditions surveyed downriver<br />

lands at Nitro and St. Albans.<br />

Meanwhile, a veteran Virginia militiaman,<br />

Colonel Thomas W. Bullitt from Prince<br />

William County, appeared in the Kanawha<br />

Valley in the spring of 1773 while on<br />

an expedition bound for the Kentucky<br />

wilderness, where he made surveys of<br />

Frankfort and Louisville. Upon his return,<br />

Bullitt was granted acreage in the western<br />

territory as a reward for military and civil<br />

service to Virginia. He chose a favorable<br />

1,030-acre site at the mouth of Elk River that<br />

he believed best for future development. His<br />

claim began at a large sycamore tree at the<br />

junction of the Elk and Kanawha Rivers and<br />

ran nearly a mile up the Kanawha to the head<br />

of the bottom; it continued 330 feet to a<br />

“Spanish Oak at the base of the hills,” then<br />

followed a direct line just over two miles to<br />

Elk River before returning back to the starting<br />

point. Bullitt also claimed a second parcel<br />

consisting of 1,240 acres directly below the<br />

west bank of Elk River and extending down<br />

to a point beyond Kanawha Two-Mile Creek.<br />

Bullitt possibly made a “tomahawk claim” to<br />

the lands in 1774, but his actual survey dates<br />

to May 25, 1775. When Thomas Bullitt died<br />

in Fauquier County in 1778, his younger<br />

brother, Cuthbert Bullitt (1740-1791), a<br />

planter, lawyer and judge from Prince William<br />

County, inherited the Kanawha lands. On<br />

November 20, 1779, Cuthbert Bullitt received<br />

a formal patent signed by Virginia Governor<br />

Thomas Jefferson that granted him ownership<br />

“in consideration of military services performed<br />

by Thomas Bullitt in the late war between<br />

Great Britain and France.”<br />

✧<br />

Colonel Thomas Bullitt’s two surveys<br />

covered 2,270 acres of prime bottomland<br />

along the east and west banks of the<br />

Elk River.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION<br />

(FROM LAIDLEY, HISTORY OF CHARLESTON AND<br />

KANAWHA COUNTY).<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

7

✧<br />

Andrew Lewis led Virginia troops at the<br />

Battle of Point Pleasant. Lewis never lived<br />

in West Virginia, but he played a prominent<br />

role in its early history and development.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF BILLY JOE PEYTON.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

8<br />

Upset by the frequency and severity of<br />

persistent Indian raids, and spurred on by<br />

speculators who hoped to gain from settling<br />

the western lands, Virginia’s royal governor,<br />

John Murray, launched an offensive against<br />

the Shawnee villages in Ohio in the autumn<br />

of 1774. Murray, who held title as the fourth<br />

Earl of Dunmore, assembled an army of<br />

around 1,200 men at Fort Dunmore (present<br />

Pittsburgh) and moved down the Ohio River.<br />

He intended to join forces with a second<br />

army of around 1,100 Virginians under<br />

Colonel Andrew Lewis, a Virginia militiaman<br />

and surveyor who had surveyed much of<br />

Greenbrier County and was a respected<br />

veteran of the French and Indian War. As<br />

Dunmore’s army moved down from the<br />

north, Lewis’s troops gathered at Fort Union<br />

(present-day Lewisburg) and on September 6<br />

began marching westward in successive<br />

waves over the trackless forest to a<br />

rendezvous point on Elk River.<br />

<strong>First</strong> to depart Fort Union<br />

was Colonel Charles Lewis<br />

(younger brother of Andrew<br />

Lewis) and 600 men of<br />

the Augusta Regiment, whose<br />

mission was “to proceed as far<br />

as the mouth of Elk, then to<br />

make canoes to take down the<br />

flour. He took with him 108<br />

beeves and 500 pack-horses<br />

carrying 54,000 pounds of<br />

flour.” Six days later, Colonel<br />

William Fleming and the<br />

Botetourt Regiment moved<br />

out with 18,000 pounds of<br />

flour. Fleming’s Botetourt force<br />

joined the Augusta troops<br />

at the mouth of Elk on<br />

September 22, “where both<br />

regiments engaged in making<br />

a store-house and building<br />

canoes for transporting supplies<br />

down the Great Kanawha.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> parole—a watchword or<br />

password issued by the<br />

commanding officer to the<br />

officers of the guard—for this<br />

day was “Charlestown,” a full<br />

fourteen years before the<br />

town at the mouth of the Elk was established.<br />

<strong>The</strong> word probably was in reference to<br />

Colonel Charles Lewis, but it would be<br />

interesting to know if it had any impact on<br />

the subsequent naming of the town that<br />

would develop later.<br />

Crews eventually constructed twentyseven<br />

canoes in about a week’s time at the<br />

mouth of Elk. At daybreak on September 30,<br />

the canoes were sent up Elk River about<br />

one-and-a half miles, where the river was<br />

“100 yards wide and there was a fording.”<br />

This would put the crossing near the<br />

mouth of Magazine Branch, about where<br />

Pennsylvania and Bigley Avenues converge<br />

today. In conditions described as “still dead<br />

running water,” cattle and packhorses were<br />

driven over first, followed by the army which<br />

crossed to a camp on the “level plain below<br />

the mouth of the Elk” on <strong>Charleston</strong>’s West<br />

Side. Incessant rains forced the men to remain<br />

in camp until October 2, when they resumed<br />

their march to the Ohio. It was during this<br />

extended encampment that Virginia soldiers<br />

first became acquainted with the fertile<br />

bottom land at the confluence of the Elk and<br />

Kanawha Rivers.<br />

Lewis’s army reached Point Pleasant on<br />

October 6, 1774. <strong>The</strong>re, on October 10, they<br />

were attacked by an equal force of Shawnees<br />

and their allies led by famed warrior, Chief<br />

Cornstalk. In a fierce day-long fight that<br />

descended into a hand-to-hand struggle, the<br />

Virginia militia prevailed after Cornstalk’s<br />

forces retreated across the Ohio River. Under<br />

terms of the Treaty of Camp Charlotte that<br />

ended Dunmore’s War, the Ohio River was<br />

recognized as the boundary between the<br />

Shawnee nation and British settlers, the<br />

Shawnee agreed to stop attacking travelers<br />

on the Ohio River, and Kentucky was closed<br />

to British settlement. Construction of Fort<br />

Randolph at Point Pleasant bolstered the<br />

sense of security for area residents. <strong>The</strong> treaty<br />

secured a temporary peace, and settlers<br />

streamed into the Kanawha Valley. Violence<br />

returned to the frontier following the brutal<br />

murder of Cornstalk at Fort Randolph in<br />

November 1777.<br />

Among the soldiers who camped at<br />

Elk River and fought at the 1774 Battle of

Point Pleasant were several sons of Charles<br />

Clendenin. Among them was George, who<br />

was born in Augusta County in 1746. <strong>The</strong><br />

Clendenin family had originally migrated to<br />

the Shenandoah Valley from Ulster, Northern<br />

Ireland, and Charles had moved his family<br />

to the Greenbrier Valley (present Pocahontas<br />

County) in 1771. Following his service in<br />

Dunmore’s War, George Clendenin represented<br />

Greenbrier County in the Virginia House of<br />

Delegates from 1781 to 1789. He helped<br />

establish the Old State Road from Lewisburg<br />

to <strong>The</strong> Boatyards (Cedar Grove) in 1786, and<br />

its extension to the mouth of the Elk River<br />

two years later. George Clendenin became a<br />

major landowner in Greenbrier County, with<br />

holdings individually and jointly in excess of<br />

30,000 acres. On December 28, 1787, while<br />

attending a legislative session in Richmond,<br />

George Clendenin purchased from Cuthbert<br />

Bullitt the 1,030-acre tract located along the<br />

Kanawha River that was part of the Thomas<br />

Bullitt survey. Clendenin later sold 507 acres<br />

to his brothers, William and Alexander.<br />

Eager to relocate to his new lands at the<br />

mouth of the Elk, Clendenin urged Virginia<br />

lawmakers to focus their attention on frontier<br />

defense. At the time, four forts existed in<br />

the entire Kanawha Valley—at Point Pleasant,<br />

the mouth of Coal River, opposite Campbell’s<br />

Creek, and on Kelly’s Creek. Each fort<br />

accommodated only about ten families, which<br />

was inadequate for reliable defense according<br />

to Clendenin—who asserted that all settlers<br />

would vacate their lands if they did not<br />

receive more protection. On January 30,<br />

1788, Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph<br />

directed George Clendenin to organize a<br />

company of rangers and to station them at<br />

a location he deemed to be most acceptable<br />

for the protection of Kanawha settlers. Not<br />

surprisingly, and with an eye to future<br />

settlement opportunities, Clendenin placed<br />

the company on his own lands near the<br />

mouth of Elk. He named his brother, William,<br />

also a veteran of the Battle of Point Pleasant,<br />

as captain, while another brother, Alexander,<br />

served as a private. At the outset, twentyseven<br />

rangers formed the militia company:<br />

George Clendenin led the first group of<br />

intrepid settlers into the Kanawha Valley in<br />

K A N A W H A M I L I T I A O R I G I N A L M U S T E R R O L L<br />

George Clendenin, colonel<br />

George Shaw, lieutenant<br />

Shadrach Harriman, sergeant<br />

John Tollypurt, private<br />

John Burns, private<br />

William Miller, private<br />

James Edgar, private<br />

Michael Newhouse, private<br />

Thomas Shirkey, private<br />

William Boggs, private<br />

Benjamin Morris, private<br />

William Morris, private<br />

William Turrell, private<br />

Alexander Clendenin, private<br />

April 1788. It is unclear whether he had<br />

recently laid eyes on his new land, but it<br />

probably changed little since 1774. Upon<br />

arrival at the Elk River, the forty-two-year-old<br />

Clendenin immediately set the Kanawha<br />

Rangers to work building a fortification which<br />

they completed in May. For the fort site, he<br />

chose a high bank overlooking Kanawha River<br />

about 125 feet above the present intersection<br />

of Brooks Street and Kanawha Boulevard.<br />

Informally called Clendenin’s Station, it<br />

offered a commanding view of the river in<br />

both directions, had a supply of fresh water<br />

nearby, and a natural ravine offered a good<br />

spot for a canoe landing. By 1792, the station<br />

had officially become Fort Lee, named in<br />

honor of Revolutionary War hero and former<br />

Virginia governor, Richard Henry Lee, father<br />

of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fortification itself consisted of a log<br />

stockade about 250 feet long and 175 feet<br />

wide, with two entry gates—one that opened<br />

on the river side and another on the hill<br />

side. Within the enclosure stood a two-story<br />

hand-hewn log structure that measured<br />

36 feet long, 18 feet wide and 18 feet high,<br />

with clapboard roof, whipsawed rafters<br />

and framing, puncheon (dirt) floor, and a<br />

fieldstone chimney on both ends. Built on a<br />

typical plan, it had two rooms and a hallway<br />

on the first floor and two rooms on the second<br />

floor. Known as the “Mansion House,” it<br />

William Clendenin, captain<br />

Francis Watkins, ensign<br />

Reuben Slaughter, sergeant<br />

Samuel Dunbar, private<br />

Isaac Snedicer, private<br />

John Buckle, private<br />

Robert Aaron, private<br />

William Carroll, private<br />

Nicholas Null, private<br />

Archer Price, private<br />

Levi Morris, private<br />

Joseph Burrell, private<br />

John Moore, private<br />

✧<br />

While serving in the Virginia state<br />

legislature, George Clendenin purchased<br />

the 1,030-acre Bullitt tract on<br />

December 28, 1787.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF SOCIETY OF THE COLONIAL<br />

DAMES OF AMERICA IN THE STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA.<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

9

✧<br />

Below: Artist’s rendering of Clendenin’s<br />

Station, later renamed Fort Lee. <strong>The</strong> fort<br />

stood near present Kanawha Boulevard,<br />

between present Brooks and Morris Streets.<br />

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION<br />

(FROM COOK, THE ANNALS OF FORT LEE).<br />

Opposite, top: Postcard of Daniel Boone<br />

originally issued by Daniel Boone Hotel<br />

in <strong>Charleston</strong>.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

Opposite, bottom: In 1928, the Daughters<br />

of the American Revolution erected a stone<br />

marker to Daniel Boone at the base of a<br />

cave near the mouth of Campbell’s Creek.<br />

<strong>The</strong> cave was obliterated in the 1970s,<br />

and the marker now stands in<br />

Daniel Boone Park.<br />

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF BILLY JOE PEYTON.<br />

served as the main residence for George<br />

Clendenin and his family. In addition, the<br />

rangers built a blockhouse about one mile<br />

upstream (in the vicinity of the Executive<br />

Mansion at the Capitol Complex) where<br />

William Clendenin and his family resided.<br />

Other scattered cabins stood on land cleared<br />

from the nearby forest.<br />

Today, near the corner of Brooks Street and<br />

Kanawha Boulevard stands a native stone<br />

marker placed in 1915 by the Kanawha Valley<br />

Chapter of the Daughters of the American<br />

Revolution to mark the site of the original<br />

Fort Lee building and stockade. Historian Roy<br />

Bird Cook surmised that the boulder stands a<br />

little in front of the actual building site.<br />

Charles Clendenin’s gravesite was somewhere<br />

in the 1200 block of Kanawha Boulevard.<br />

In 1917, the National Society of the Colonial<br />

Dames of America (NSCDA) in the State of<br />

West Virginia erected a marble-based sundial<br />

in the memory of Charles Clendenin, the<br />

father of George who died at Fort Lee in<br />

1790 and was buried within its stockade. <strong>The</strong><br />

sundial was moved to its present location<br />

opposite 1254 Kanawha Boulevard in 1988,<br />

and in 2012 underwent restoration under<br />

a joint effort of NSCDA-West Virginia, the<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> Beautification Commission, and<br />

the <strong>Charleston</strong> Public Works Department.<br />

Danger took many forms in the exposed<br />

and vulnerable frontier settlements, but the<br />

most imminent and potentially lethal threat<br />

came from marauding bands of native<br />

warriors who hoped to roll back the tide of<br />

settlement. <strong>The</strong>y hoped to accomplish their<br />

goals by launching raids deep into the<br />

Kanawha Valley, where they stole horses,<br />

destroyed cabins and crops, took prisoners,<br />

and sometimes brutally murdered settlers.<br />

When the call went out to “fort up,” residents<br />

sought protection and the Kanawha Rangers<br />

sprang into action until danger had passed.<br />

Once, during construction of Fort Lee, a<br />

raiding party of twenty-two Indians appeared<br />

but quickly dispersed after the militia force<br />

showed itself in strength.Unfortunately, other<br />

clashes did not end so well.<br />

Local victims included James Hale, who<br />

was killed at Hale’s Branch on the south side<br />

of Kanawha River (near present South Side<br />

Bridge) in 1789 and buried in a small plot in<br />

the fort near the later grave of Charles<br />

Clendenin. In 1790 a deadly attack on Fort<br />

Tackett on Coal River (St. Albans) about<br />

twelve miles downstream sent survivors<br />

scurrying for refuge at Fort Lee. Shadrach<br />

Harriman, an original <strong>Charleston</strong> settler and<br />

member of the Kanawha Rangers, was killed<br />

near Venable Branch (now Mission Hollow)<br />

in 1791. Such persistent violence led George<br />

Clendenin to declare the Kanawha Valley<br />

as “one continual scene of depradation [sic]”<br />

by 1792.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

10

Following the erection of Fort Lee, the<br />

politically astute George Clendenin turned<br />

his attention to creating the framework for<br />

a permanent settlement at the mouth of Elk<br />

River. Largely through Clendenin’s efforts, on<br />

November 14, 1788, the legislature authorized<br />

the formation of Kanawha County from<br />

Greenbrier and Montgomery counties, with the<br />

actual formation set for October 1, 1789. <strong>The</strong><br />

new county encompassed most of the present<br />

southwestern portion of the state, including all<br />

or parts of nineteen modern counties and the<br />

entire Kanawha River. On October 5, 1789, the<br />

Kanawha County Court held its first session at<br />

George Clendenin’s residence inside Fort Lee.<br />

<strong>The</strong> justices recommended veteran frontiersman<br />

Daniel Boone to serve as lieutenant colonel of<br />

the county militia. This designation made<br />

Boone the third-ranking officer in the county,<br />

following Sheriff Thomas Lewis and militia<br />

commander, Colonel George Clendenin. By<br />

then, Daniel Boone had already made his<br />

reputation as a scout who blazed the Wilderness<br />

Road and led settlers into Kentucky.<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

1 1

Boone, his wife Rebecca, and their three<br />

youngest children, Daniel (b. 1769), Jesse<br />

(b. 1773), and Nathan (b. 1780), moved to<br />

Point Pleasant sometime in 1788, where<br />

the elder Daniel reputedly operated a small<br />

trading post, engaged in occasional surveying<br />

work, and hunted and trapped along<br />

Kanawha River. In years of living on the<br />

frontier, Boone had more than one narrow<br />

escape from Indians. In December 1789,<br />

a report circulated among the Kanawha<br />

settlements that Indians “have killed young<br />

Daniel Boone and took his father old<br />

Col. Boone prisoner.” With no evidence to<br />

the contrary, George Clendenin feared the<br />

news was true. In the end, the report proved<br />

false. <strong>The</strong> Boones had tarried to hunt and<br />

trap on a return trip from Philadelphia, and<br />

they eventually arrived safely home in early<br />

1790. On another occasion, when Boone<br />

failed to return as scheduled from his annual<br />

winter hunt in 1793, even his stalwart wife,<br />

Rebecca, began to worry. Local concern gave<br />

rise to a report in the United States Gazette<br />

from April 1793 that Boone had been “killed<br />

or taken.” Once again, the account of his<br />

demise proved premature when he returned<br />

unscathed to <strong>Charleston</strong>.<br />

Daniel Boone’s reputation as an intrepid<br />

frontiersman had already grown to mythical<br />

proportions when he decided to try his<br />

hand at political office. In the first elections<br />

in 1790, George Clendenin and Andrew<br />

Donnally represented Kanawha County in the<br />

Virginia Assembly. In April 1791, Daniel<br />

Boone traveled from his home at Point<br />

Pleasant to the polling place at Fort Lee,<br />

where he participated in an “open and fair<br />

election” to decide who would represent<br />

Kanawha County at the next legislative term<br />

in Richmond. By day’s end, George Clendenin<br />

and Daniel Boone had been chosen to<br />

represent the county. As the legislative session<br />

approached, Boone dutifully walked to<br />

Richmond and took his seat.<br />

While in Richmond, Boone negotiated a<br />

contract to provide ammunition and rations<br />

for militia units at Moorefield, Morgantown,<br />

Wheeling and elsewhere. After fulfilling those<br />

contracts he returned to Point Pleasant in<br />

April 1792 with insufficient supplies, which<br />

infuriated Hugh Caperton who commanded<br />

the rangers there. A heated argument ensued,<br />

in which Caperton accused Boone of incompetence<br />

for failing to bring the needed<br />

provisions to the fort. In a written report to<br />

the governor, George Clendenin blamed<br />

Boone for “total non-compliance” with respect<br />

to his contractual obligations, which resulted<br />

in Boone losing his supply contract and<br />

ultimately closing his store at Point Pleasant.<br />

In search of a simpler life free from legal<br />

and financial entanglements, Daniel and<br />

Rebecca Boone, their sons Nathan and Jesse,<br />

and Jesse’s wife, Chloe Van Bibber Boone,<br />

relocated sixty miles upriver to the mouth<br />

of Elk in 1791 or 1792. Boone knew the<br />

favorable natural attributes of the Upper<br />

Kanawha Valley, which appealed to him.<br />

He was personal friends with Simon Kenton,<br />

who had hunted and trapped along the<br />

Kanawha and Elk Rivers and had saved<br />

Boone’s life in Kentucky. Boone hunted and<br />

trapped in the area, and he well knew the<br />

famed salt marshes at Campbell’s Creek. In<br />

addition, he had rescued from captivity a local<br />

girl named Chloe Flinn, who had been taken<br />

when her parents were killed by Indians at<br />

their home near Cabin Creek (about twelve<br />

miles above <strong>Charleston</strong>) in 1786. Following<br />

her liberation, Daniel and Rebecca Boone<br />

raised the orphaned Chloe in their home.<br />

When they settled near Elk River, the<br />

Boone family took up residence in a cabin that<br />

stood on land owned by Andrew Donnally,<br />

Sr., on the south side of Kanawha River<br />

about four-and-a-half miles above Fort Lee.<br />

According to historian Roy Bird Cook in<br />

<strong>The</strong> Annals of Fort Lee (1935), “<strong>The</strong> Boone<br />

home was a double log house which stood in<br />

or near the upper end of Kanawha Avenue,<br />

in Kanawha City…and in sight of the capitol<br />

building of West Virginia.” Cook describes<br />

it “as a favorable place of residence,<br />

commanding a good view of a slight bend<br />

in the Kanawha River, and the mouth of<br />

Campbell’s Creek, where were located the<br />

celebrated salt licks later developed by the<br />

Dickinsons and others.” Although the cabin’s<br />

exact location is unknown, Cook surmises<br />

that it stood near the old Donnally family<br />

cemetery on the south side of Kanawha<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

12

Avenue at Fifty-seventh Street. <strong>The</strong> old burial<br />

ground no longer exists, and the remains of<br />

those interred there were moved to the<br />

Old Circle section of Spring Hill Cemetery<br />

many years ago.<br />

Peace finally came to the Kanawha frontier<br />

when U.S. troops under General “Mad”<br />

Anthony Wayne defeated a Native American<br />

force in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Ohio, on<br />

August 20, 1794, and the Treaty of Greenville<br />

was signed about a year later. Settlers<br />

welcomed the fact that defense was no longer<br />

their top priority, but it meant that Daniel<br />

Boone’s days as a border defender and<br />

member of the Virginia militia had ended. In<br />

1795, the sixty-year-old Boone, his wife<br />

Rebecca and their son Nathan packed their<br />

meager possessions and departed Fort Lee<br />

on a flatboat bound for Kentucky. Son Jesse<br />

and wife, Chloe, remained in the area until<br />

1797, when they joined the others. Later,<br />

Daniel Boone moved to Missouri, where the<br />

venerable patriarch died in 1820 at the age<br />

of eighty-five.<br />

After working out organizational details<br />

for Kanawha County, local officials turned<br />

their attention to erecting public buildings.<br />

A crude jail was built in 1792, followed by<br />

a courthouse in 1796 on a lot near the center<br />

of town purchased from George Alderson.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first county clerk’s office stood near the<br />

corner of present Hale Street and Kanawha<br />

Boulevard. When frontier hostilities ended,<br />

George Clendenin and other county officials<br />

urged the state to establish a permanent<br />

settlement. On December 19, 1794, the<br />

legislature complied by designating a fortyacre<br />

tract of George Clendenin’s land as the<br />

site of a town which Clendenin officially<br />

named Charlestown (or Charles Town) in<br />

honor of his father, Charles, who had died at<br />

Fort Lee in 1790 and was buried inside<br />

the stockade.<br />

Alexander Welch, surveyor for Greenbrier<br />

County, prepared the first plat with thirtysix<br />

lots for the “town at the mouth of Elk”<br />

before 1794. Reuben Slaughter, Kanawha<br />

County surveyor, later extended the Welch<br />

survey eastward to present Dunbar Street.<br />

<strong>The</strong> original town boundary started at the<br />

east bank of Elk River and extended to<br />

present Capitol Street. Two east-west running<br />

thoroughfares, Front Street (later Kanawha<br />

Street then Kanawha Boulevard) and Main<br />

Street (Virginia Street) ran the length of the<br />

town, bisected by five unnamed north-south<br />

streets. Purchasers of the first six town lots<br />

were Josiah Harrison, Francis Watkins,<br />

Charles McClung, Alexander Welch, John<br />

Edwards, and Shadrach Harriman, and<br />

the first trustees were Reuben Slaughter,<br />

Andrew Donnally, Sr., William Clendenin,<br />

John Morris, Abraham Baker, John Young,<br />

and William Morris.<br />

✧<br />

Engraving of an elderly Daniel Boone<br />

hunting in Missouri. He moved with his<br />

family to Missouri in 1799, and lived there<br />

until his death in 1820.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

1 3

<strong>Charleston</strong> grew slowly in the early years.<br />

<strong>The</strong> estimated population stood at about<br />

35 residents in 1795, and expanded to twelve<br />

houses and 65 residents by 1800. By that<br />

time, George Clendenin had become disillusioned<br />

with the slow pace of development,<br />

and in 1796 he sold his acreage on Elk River<br />

to Joseph Ruffner. Clendenin and his wife<br />

then relocated to the east side of Ohio River<br />

near Point Pleasant, and George died the<br />

following spring while visiting his daughter<br />

in Marietta, Ohio.<br />

Samuel Williams, a resident of <strong>Charleston</strong><br />

from 1803-1810, penned a pleasant description<br />

of the little settlement which later<br />

appeared in serial form in the Ladies Repository<br />

under the title, “Leaves from a Portfolio”<br />

(1851-54):<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> was at this time—1803—an<br />

inconsiderable village, with a population of<br />

about one hundred and fifty souls. <strong>The</strong><br />

houses were mostly constructed of hewn<br />

logs, with a few frame buildings, and, in the<br />

background, some small round-log cabins.<br />

<strong>The</strong> principal, or Front street, some sixty feet<br />

in width, was laid out on the beautiful bluff<br />

bank of the Kanawha River, which has an<br />

elevation of thirty or forty feet above low<br />

water. On the sloping bank between this<br />

street and the river, there were then no<br />

houses nor structures of any kind, as it was<br />

considered the common property of the town.<br />

On this street, of half a mile in length, stood<br />

about two-thirds of the houses composing the<br />

village. On another street, running parallel to<br />

this, and at a distance of some four hundred<br />

feet from it, and only opened in part, there<br />

were a few houses. <strong>The</strong> remainder lay upon<br />

cross streets, flanking the public square.<br />

<strong>The</strong> houses were constructed in plain,<br />

back-woods style; and to the best of my<br />

recollection, the painter’s brush had not<br />

passed upon any of them. <strong>The</strong> streets<br />

remained in their primitive state of nature,<br />

except that the timber had been cut off by<br />

the proprietor, who had originally cultivated<br />

the ground as a corn-field. But the sloping<br />

bank of the river, in front of the village, was<br />

still covered with large sycamore trees and<br />

paw-paw bushes. Immediately in the rear of<br />

the village lay an unbroken and dense forest of<br />

large and lofty beech, sugar, ash, and poplar<br />

timber, with thickets of paw-paw. Above, and<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

14

adjoining it, lay the beautiful farms of the<br />

Ruffner family, extending in succession, three<br />

or four miles up the river, and covering the<br />

rich alluvial bottom. About a mile in the rear<br />

of the village, and near the base of the hills<br />

bounding the Valley, lay the farm and pleasant<br />

mansion of Colonel John Reynolds…. Below,<br />

at a distance of a quarter of a mile, the<br />

Elk River, flowing in at right angles, united<br />

its placid waters with those of the Kanawha.<br />

<strong>The</strong> space between the Elk River and the<br />

village was covered with a heavy growth of<br />

sycamore trees, and with paw-paw thickets.<br />

Williams described the public square,<br />

present site of the courthouse, as near the<br />

center of the village, without any enclosure<br />

and extending from Front to Second (now<br />

Virginia) Street. <strong>The</strong> courthouse was an<br />

unpainted log building that stood about<br />

30 feet back from Front Street and featuring<br />

a plain, unadorned courtroom. A few feet<br />

south of the courthouse, and about 30 feet<br />

farther back, stood the log jail with two<br />

cells—one for debtors and the other for<br />

criminals. Williams mockingly described<br />

“those ornaments of a refined and enlightened<br />

age—the whipping-post, pillory and stocks”<br />

which stood in front of the jail near the south<br />

end of the courthouse. Law officers utilized<br />

these remnants of a bygone era to mete out<br />

punishment ranging from public lashing to<br />

tossing rotten eggs at guilty perpetrators.<br />

Among the responsibilities of the county<br />

court in the early days was to set prices that<br />

innkeepers could charge for food and drink,<br />

and to authorize a bounty for wolf scalps.<br />

<strong>The</strong> court also heard a variety of legal cases,<br />

including one in 1796 for an individual<br />

found guilty of contempt for “profane<br />

swearing,” and an individual fined in 1797<br />

for “having hunted on the Sabbath and<br />

boasted about it.” Another 1797 case ordered<br />

protection for a slave named Ned, alias<br />

Dennis Canaday, who had apparently<br />

suffered physical abuse at the hands of his<br />

owner, Samuel Fuqua.<br />

Annual state elections were held each<br />

April with three days of voting at the<br />

courthouse. On those occasions, large crowds<br />

descended on the town to cast ballots and<br />

socialize. Only freeholders could legally vote<br />

under Virginia law, but there were so<br />

few property owners in Kanawha County that<br />

the requirement was waived by common<br />

consent, according to Williams. Although not<br />

strictly legal, he claimed that all white males<br />

could vote, along with minors and travelers<br />

who happened to pass through the area<br />

during elections.<br />

✧<br />

Opposite: Original plat as drawn by<br />

Alexander Welch before 1794.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION<br />

(FROM LAIDLEY, HISTORY OF CHARLESTON AND<br />

KANAWHA COUNTY).<br />

Above: A later published version titled<br />

Plan of Town at the Mouth of Elk.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION<br />

(FROM ATKINSON, HISTORY OF KANAWHA COUNTY).<br />

C H A P T E R 1<br />

1 5

✧<br />

Kanawha Courthouse remained the official<br />

postal designation until 1879, when the<br />

Post Office Department adopted <strong>Charleston</strong>.<br />

COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS,<br />

PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION,<br />

HTTP://WWW.LOC.GOV/PICTURES/ITEM/2011660250/<br />

<strong>The</strong> Post Office Department officially designated<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> as Kanawha Courthouse<br />

when the first post office opened in 1801.<br />

Mail arrived once every two weeks, delivered<br />

on horseback from Lewisburg about 100<br />

miles distant. Families were often supplied<br />

with parcels of coffee, tea, spices, and other<br />

desirable household commodities delivered<br />

with the mail.<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong>’s early settlers were primarily<br />

yeoman farmers who pursued modest<br />

agricultural production. Corn and hogs<br />

made up the bulk of farm production, while<br />

hunting, trapping and fishing supplied food<br />

for the home table, as well as potential<br />

economic gain through sale or barter of any<br />

surplus. Modest growth raised <strong>Charleston</strong>’s<br />

population to about 100 residents and twenty<br />

houses in 1810. <strong>The</strong> town had the added<br />

advantage of being the seat of Kanawha<br />

County, which had suffered large territorial<br />

losses but increased overall population to<br />

3,866 white residents, 352 enslaved African<br />

Americans, and 46 “free persons, excluding<br />

Indians” by 1810, a net increase of about<br />

sixteen percent in a decade. Many landowners<br />

had begun to acquire sizable acreage and<br />

erect substantial dwellings, but overt class<br />

differences among whites were not obvious in<br />

the first decades of the 1800s.<br />

When the War of 1812 began, residents<br />

rallied to the patriotic cause. Troops led by<br />

local officers like Colonel David Ruffner,<br />

Major John Stark, Major Claudius Buster,<br />

Captain Silas Reynolds, and Captain John<br />

Wilson faithfully served in the conflict<br />

which lasted until early 1815. <strong>The</strong> war also<br />

launched a new industrial economy based<br />

on salt production. “Kanawha salt” gained<br />

a substantial share of the domestic market<br />

after the United States banned imports from<br />

British possessions in the Caribbean, which<br />

made it possible for local producers to<br />

take control of western markets that had<br />

previously been monopolized by West Indian<br />

salt. As a result of the booming salt industry,<br />

Malden emerged as the first center of<br />

industrial production in the Kanawha Valley,<br />

and, <strong>Charleston</strong> remained a relatively small<br />

county seat.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

16

C H A P T E R 2<br />

TOWN AT THE MOUTH OF ELK<br />

1820-1860<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kanawha salt industry traces its commercial origins to 1797, less than a decade after<br />

construction of Fort Lee. Colonel John Dickinson, a veteran of the Battle of Point Pleasant and<br />

resident of Bath County, Virginia, owned two tracts of land along the Kanawha River that he had<br />

surveyed in November 1784. One was 704 acres in the area of present Belle, and the other a 502-<br />

acre parcel at the mouth of Campbell’s Creek that included the famous brine springs where Mary<br />

Ingles’ Shawnee captors had stopped to make salt three decades earlier. In 1796, Dickinson sold<br />

the salt lands to Joseph Ruffner, Sr., from Massanutten, near Luray, in the Shenandoah Valley of<br />

Virginia. Elisha Brooks leased the salt spring from Ruffner in 1797, where he built a small furnace<br />

consisting of about two dozen kettles set in rows with a flue beneath them. Brooks<br />

sank hollow logs (or gums) into shallow wells and drew out enough brine with a “swape” (sweep)<br />

to make 150 pounds of salt a day, which he sold at the furnace for eight to ten cents a pound.<br />

When Joseph Ruffner, Sr., died in 1802, sons David and Joseph inherited his salt lands. <strong>The</strong><br />

pair made numerous advances in drilling technology, and in 1808 they sank deeper wells<br />

to hit stronger brine that yielded a bushel of salt for every 200 gallons of liquid, which raised<br />

capacity to 1,250 pounds per day and reduced the cost to four cents a pound. <strong>The</strong> Ruffner brothers<br />

continued to innovate, and on January 18, 1817, David and Joseph received a patent<br />

for a “mode of obtaining salt water.” Unfortunately, details were lost in a fire at the U.S. Patent<br />

Office in 1836. Later, David and Joseph Ruffner’s younger brother, Tobias, successfully used<br />

horsepower to sink a well to a depth of 410 feet, which tapped brine so strong that 45 gallons<br />

produced a bushel of salt. Technological improvements pioneered by the Ruffners, combined with<br />

increasing demand for salt in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, led to a drilling frenzy along<br />

both sides of Kanawha River for ten miles between <strong>Charleston</strong> and Brownstown (present Marmet).<br />

✧<br />

Ashton Woodman Renier’s 1926 rendering<br />

of the Kanawha & James River Turnpike,<br />

which became known as the Midland Trail<br />

during the automobile era.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION,<br />

(FROM RENIERS, THE MIDLAND TRAIL TOUR).<br />

C H A P T E R 2<br />

1 7

✧<br />

This comprehensive map of Kanawha salt<br />

furnaces operating prior to the Civil War<br />

includes fifty-seven identified and<br />

eight unknown locations.<br />

MAP COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

(FROM THE SALT INDUSTRY IN THE KANAWHA VALLEY).<br />

By 1815, some 52 furnaces lined both riverbanks<br />

and produced up to 3,000 bushels of<br />

salt daily, and three times that by the late<br />

1840s. With its center at Malden (or Kanawha<br />

Salines), Kanawha Valley salt became the<br />

major export commodity in all of trans-<br />

Allegheny Virginia.<br />

Production grew steadily until 1846,<br />

when area operations led the nation with a<br />

total yield of 3.2 million bushels. Salt making<br />

had a profound ripple effect on the local<br />

economy by spurring a number of ancillary<br />

industries and creating hundreds of jobs for<br />

coopers, boat builders, sawmill operators,<br />

and more. With tremendous industrial<br />

growth, practically all viable trees in close<br />

proximity to the furnaces had been cut and<br />

burned within a fairly short time, prompting<br />

operators to turn to coal as fuel. David Ruffner<br />

became the first operator to use coal, and<br />

virtually all operators converted to it by<br />

1822. As a result coal mines opened along<br />

Kanawha River to create the area’s first<br />

industrial mining jobs. Inventiveness led<br />

the way for other improvements in drilling<br />

and pumping technology. Local innovators<br />

included driller William “Uncle Billy” Morris<br />

who invented the “slips” or “jars,” a doubleacting<br />

bit that made deeper rock drilling<br />

possible. Jars became an industry standard<br />

and are still in use today. Edwin Drake<br />

employed well-diggers from Kanawha to<br />

make the first successful oil strike at<br />

Titusville, Pennsylvania.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

18

Another significant contribution of the<br />

Kanawha salt producers was a business innovation<br />

that is commonplace today but was<br />

unknown in the early 1800s. In an attempt to<br />

control output and markets, local producers<br />

created legal combinations that included<br />

output pools, lease contracts, joint stock<br />

companies, and a proposed trust that were<br />

the first of their type in the nation. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

efforts originated with over-expansion of<br />

the Kanawha Valley salt industry during the<br />

boom years surrounding the War of 1812. As<br />

a result, prices fell below manufacturing and<br />

distribution costs, causing salt companies<br />

to fail. At war’s end, vast amounts of imports<br />

from the West Indies flooded local markets<br />

and forced Kanawha producers to sell their<br />

salt at steeply reduced prices. To meet the<br />

revived competition, and help curtail overproduction,<br />

producers in 1817 formed the<br />

Kanawha Salt Company, an output pool and<br />

central sales agency for member producers<br />

that attempted to limit production and assign<br />

quotas to each member. Considered to be the<br />

earliest known output pool in the U.S., it met<br />

with varying levels of success and operated<br />

in some form or other for about fifteen years.<br />

<strong>The</strong> promise of economic gain enticed<br />

many individuals to enter the local salt<br />

business. By 1815 one source observed that<br />

area producers had “almost unbounded<br />

wealth.” Included among them were members<br />

of the Ruffner, Dickinson, Shrewsbury,<br />

Lewis, Brooks, Donnally, Quarrier, Noyes, and<br />

Tompkins families—not coincidentally, these<br />

would be the same names which dominated<br />

the region’s antebellum public and political<br />

life. It should come as no surprise that many<br />

of these pioneer families were among the first<br />

generation of entrepreneurs to also develop<br />

the region’s timber, coal, and natural gas<br />

resources, and remain local scions of industry<br />

(and philanthropy) to the present day.<br />

Antebellum salt-making enterprises obviously<br />

created opportunity and wealth for some<br />

residents, but prosperity came at a high price<br />

because the industry firmly established slavery<br />

as a primary source of labor in the antebellum<br />

period. To be sure, slavery had existed in<br />

Kanawha County since its founding, but the<br />

number of enslaved African Americans and<br />

white owners were both low, as indicated by<br />

the 1792 personal property list for the county<br />

which records 25 slaves above 16 years of age<br />

and only 17 slave owners. In that year, the<br />

estate of William Morris (who died in 1792)<br />

held four slaves, the highest number owned by<br />

one individual. By 1801, the total number of<br />

slaves over the age of 16 grew to 121 and those<br />

over 12 years of age increased to 27 individuals<br />

(148 total), while 70 whites owned slaves.<br />

In that year, seven different whites held more<br />

than five slaves, with Joseph Childers owning<br />

seven individuals.<br />

Prior to the War of 1812, salt producers<br />

had viewed “the hardy sons of yeomanry as<br />

best adapted to the toils and privations of the<br />

business.” However, a persistent labor shortage<br />

in the burgeoning industry made it possible<br />

for area salt makers to turn overwhelmingly<br />

to slavery. As a result, slave labor evolved<br />

into a dominant corporate enterprise by the<br />

mid-1800s; the largest and most influential<br />

salt operators had become big-time slave<br />

owners or lessees by 1850, when Kanawha<br />

County’s enslaved population reached an alltime<br />

high of 3,140 individuals. <strong>The</strong>y included<br />

the firm of Dickinson & Shrewsbury with 232<br />

slaves, John N. Clarkson with 153, Andrew<br />

Donnally & Company with 120, Joseph<br />

Friend and John D. Lewis with 109, and<br />

Samuel H. Early with 73 slaves. At least half of<br />

the county’s slaves worked in the salt industry.<br />

In addition to the stain of industrial slavery,<br />

the never-ending smoke emanating from<br />

the salt works led to environmental degradation<br />

in and around Malden. To escape the<br />

foul air and water, as well as the so-called<br />

“rough elements” around the furnaces, some<br />

salt makers began to relocate a few miles<br />

downriver (and upwind) to <strong>Charleston</strong> by the<br />

1820s, where they built large and stately<br />

homes along the waterfront. <strong>The</strong>se residents<br />

helped <strong>Charleston</strong> transition from a sleepy<br />

Southern village into a bustling river town<br />

with a growing number of churches, schools,<br />

businesses, and other amenities.<br />

One early observer of the salt operations<br />

was Anne Newport Royall, considered by<br />

some to be the first professional woman<br />

journalist in the United States. Anne relocated<br />

from Monroe County to <strong>Charleston</strong> after<br />

C H A P T E R 2<br />

1 9

✧<br />

Top, left: After the War of 1812, the<br />

Kanawha salt industry increasingly relied<br />

on slave labor to perform essential tasks,<br />

including working the furnaces, coopering,<br />

or packing and loading salt.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

(FROM KING, THE GREAT SOUTH).<br />

Top, right: At one time, John P. Hale owned<br />

the Betty Lovell, Snow Hill, White Hawk,<br />

and McMullins salt furnaces, which yielded<br />

1,500 bushels per day, making him the<br />

area’s leading producer.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

(FROM KING, THE GREAT SOUTH).<br />

Right: This courthouse was erected in 1817<br />

to replace the original 1796 log building.<br />

It stood until the present courthouse was<br />

constructed on the site in 1892.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

her husband, William Royall, died in 1812.<br />

She lived uneventfully in <strong>Charleston</strong> until<br />

about 1817, when she sold her house and<br />

two lots to fund a life-changing trip to<br />

Alabama, stating that “hitherto, I have only<br />

learned mankind in theory—but I am now<br />

studying him in practice.” She traveled<br />

extensively from Louisiana to Maine in the<br />

early 1820s and published her observations<br />

as Sketches of History, Life and Manners in the<br />

United States (1826), a work that firmly<br />

established her reputation. Anne settled in<br />

Washington and in 1831 published Paul Pry,<br />

a newspaper that exposed political corruption<br />

and fraud, followed by <strong>The</strong> Huntress in<br />

1836. For thirty years she struggled to keep<br />

the nation informed. A passionate patriot, her<br />

spirit and tenacity survive in her writings.<br />

Anne Royall died in 1854 and is buried in<br />

the Congressional Cemetery in Washington.<br />

In her travels through the Kanawha Valley in<br />

1823, she described the industrial scene at<br />

Kanawha Salines:<br />

In contrast, Royall described an altogether<br />

different landscape but a few miles downriver:<br />

Elks are often seen at the head of Elk river,<br />

which empties into Kenhawa [sic] river at a<br />

little town of <strong>Charleston</strong>, the seat of justice<br />

for this county…. In this town are four stores,<br />

two taverns, a court-house, a jail and an<br />

academy; the three last are of brick; and a<br />

post-office, a printing press and some very<br />

handsome buildings.<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

20<br />

<strong>The</strong>se salt-works are dismal looking<br />

places; the sameness of the long low sheds;<br />

smoking boilers; men, the roughest that can<br />

be seen, half naked; hundreds of boat-men;<br />

horses and oxen, ill-used and beat by their<br />

drivers; the mournful screaking of the<br />

machinery, day and night; the bare, rugged,<br />

inhospitable looking mountain, from which<br />

all the timber has been cut, give to it a<br />

gloomy appearance.

At the time, <strong>Charleston</strong>’s population stood<br />

at around 500 residents. (Not before 1830<br />

would the town be designated separately<br />

from Kanawha County in the federal census.)<br />

Its transformation from a frontier village to a<br />

small, but modern, seat of government had<br />

begun in 1817, when the old log courthouse<br />

was replaced with a new and modern brick<br />

structure. With its population on the rise,<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> gained legislative approval to<br />

extend its boundaries on February 4, 1825,<br />

and in 1833 to raise $10,000 by lottery for<br />

paving its streets. In 1829, a sturdy new jail<br />

was added to the courthouse complex.<br />

According to resident Joel Ruffner, “No one<br />

ever escaped from that jail except by means<br />

of the doorway.”<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong>’s transition from a struggling<br />

frontier outpost to a promising little village<br />

would not have been possible without internal<br />

improvements. As early as 1784, George<br />

Washington urged Governor Benjamin<br />

Harrison to link the eastern and western<br />

regions of Virginia with suitable transportation.<br />

At Harrison’s urging, the legislature<br />

chartered the James River and Kanawha<br />

Canal Company in 1785. Also, in that year, it<br />

authorized a state road to be constructed from<br />

Lewisburg to Kanawha Falls along the general<br />

path of the trail used by Andrew Lewis’ army<br />

on their march to Point Pleasant in 1774.<br />

<strong>The</strong> route had originated as a meandering<br />

game trail used by Native Americans to reach<br />

the Kanawha Licks on Campbell’s Creek. In<br />

1791, the road was improved to the head of<br />

navigation on Kanawha River at Kelly’s Creek,<br />

where westward travelers secured bateaux or<br />

flatboats to travel further downriver.<br />

Opened to the Ohio River by 1800, the<br />

Old State Road became a toll route in 1809.<br />

However, the growing importance of Kanawha<br />

salt soon required a more reliable all-weather<br />

passage, so Virginia in 1820 authorized the<br />

James River Company to construct a new<br />

overland route to Kanawha Falls as part of the<br />

James River and Kanawha Canal project. By<br />

1824, the James River and Kanawha Turnpike<br />

(or, Kanawha turnpike for short) ran from<br />

Lewisburg to the north bank of Kanawha<br />

River at Montgomery’s Ferry, twenty-five<br />

miles above <strong>Charleston</strong>. In 1829, the Virginia<br />

legislature authorized extending the route to the<br />

mouth of the Big Sandy River on the Ohio.<br />

Completed in 1832, it crossed the Kanawha<br />

River at <strong>Charleston</strong>, passed through Coalsmouth<br />

(St. Albans) and followed Teays Valley to the<br />

Mud River. It then bridged the Guyandotte<br />

River at Barboursville and terminated at<br />

Kenova on the Ohio, with a branch extending<br />

to nearby Guyandotte. A weekly stage line<br />

began operating between Lewisburg and<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> in 1827, and service soon continued<br />

to Kentucky. Eventually, stages operated on<br />

a daily basis to Guyandotte on the Ohio River.<br />

In 1831, the stages began carrying the<br />

mail. Well-to-do travelers in finely adorned<br />

carriages shared the route with peddlers,<br />

beggars and immigrants on foot, but they<br />

all yielded to the great livestock drives that<br />

took place in the fall. Drovers moved an<br />

estimated 60,000 hogs annually over the<br />

road. Following the so-called ‘‘central line,’’<br />

the Kanawha Turnpike remained an important<br />

passage until completion of the Chesapeake<br />

and Ohio Railroad after the Civil War.<br />

✧<br />

Travelers commonly encountered large<br />

hog drives in the fall along the Kanawha<br />

Turnpike, which created traffic jams on<br />

the road.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION, (FROM<br />

HARPER’S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 1857).<br />

C H A P T E R 2<br />

2 1

✧<br />

Above: Four-horsepower stagecoaches were<br />

a common site on the Kanawha Turnpike,<br />

but faster six-team “cannonball” stages<br />

caught the attention of bystanders when<br />

they thundered by.<br />

ILLUSTRATION COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY<br />

OF CONGRESS, AMERICAN MEMORY COLLECTION,<br />

HTTP://MEMORY.LOC.GOV/AMMEM/NDLPCOOP/MOAHTML/<br />

TITLE/SCMO_VOLS.HTML<br />

Right: April 2, 1828 edition of Western<br />

Virginian announcing new packet service<br />

between <strong>Charleston</strong> and Cincinnati.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Samuel Shrewbury house still<br />

stands at Belle.<br />

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.<br />

In addition to a growing network of overland<br />

routes, <strong>Charleston</strong> really came into its<br />

own as a river town. For many years flatboats<br />

moved downriver, and keelboats later traveled<br />

to and from <strong>Charleston</strong> with limited<br />

cargo and passengers. However, impediments<br />

on Kanawha River in the form of ten separate<br />

rapids or shoals between <strong>Charleston</strong> and<br />

Point Pleasant caused numerous wrecks,<br />

sometimes with loss of life and cargo.<br />

Johnson Shoals at Scary Creek and Red<br />

House Shoals between present Red House<br />

and Winfield were the most treacherous.<br />

<strong>The</strong> advent of steamboat technology led to<br />

calls for river improvements, and in 1819<br />

the legislature authorized a sluice navigation<br />

project to clear channels, dredge bars, and<br />

excavate “dug chutes” at dangerous locations.<br />

In December 1820, nine years after the<br />

advent of steamboat travel on the Ohio<br />

River, the 230-ton Andrew Donnally successfully<br />

H I S T O R I C C H A R L E S T O N<br />

22

navigated the Kanawha hazards and became<br />

the first steamboat to reach <strong>Charleston</strong>. Three<br />

years later, the sidewheeler Eliza duplicated<br />

the feat. Built for the salt trade, she took on a<br />

load of salt at Kanawha Salines and shipped<br />

it to Cincinnati. Although it would prove<br />

to be Eliza’s sole voyage up the Kanawha,<br />

steamboats regularly operated to the salt<br />

furnaces and packet boat service connected<br />

<strong>Charleston</strong> with Point Pleasant, Cincinnati,<br />

Parkersburg and Pittsburgh by 1825. River<br />

traffic increased steadily through the years,<br />

and in 1842 a total of 156 steamboats<br />

docked at the wharf. By then, <strong>Charleston</strong> had<br />

cemented its standing as a river destination.<br />

As with other towns and villages across<br />

Virginia, efforts to establish formal educational<br />

institutions in <strong>Charleston</strong> faced obstacles<br />

in the early 1800s. Persistent illiteracy<br />

stemmed in part from the harsh realities<br />

of life in a wilderness setting, as pioneer<br />

settlers came to place more value on knowledge<br />

and skills learned in the home, on<br />

the farm and in the forest, and less on<br />

formal education. In time, public apathy<br />

became commonplace.<br />

<strong>The</strong> historical record is vague on early<br />

education, but a school apparently existed at<br />

William Morris’s settlement on Kelly’s Creek<br />

by 1798. It was possibly the first school in<br />

the Kanawha Valley, and somewhat of an<br />

exception. Generally, students attended<br />

private subscription schools where parents or<br />

other subscribers had to pay tuition. School<br />

terms lasted about two months, and the quality<br />

of learning varied greatly. Educational<br />

opportunities for less economically advantaged<br />

children opened up in 1810, when<br />

Virginia established the Literary Fund which<br />

made money available for each county to<br />

educate the children of indigent families.<br />

Commissioners determined the number of<br />