Shakespeare Magazine 14

Hamlet is the theme of Shakespeare Magazine Issue 14, with each and every article devoted to the fictional Prince of Denmark and the play that bears his name. Rhodri Lewis asks “How Old is Hamlet?” while Samira Ahmed wonders “Why do Women Love Hamlet?” and we review recent productions of the play starring Tom Hiddleston and Andrew Scott. There's a set report from the making of Daisy Ridley's Ophelia movie and a visit to Hamlet's historic home, Kronborg Castle. We also delve deep into the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive's Hamlet collection, while Gyles Brandreth tells us about his family production of the play, and Alice Barclay recounts how she taught a group of amateur actors to become Hamlet.

Hamlet is the theme of Shakespeare Magazine Issue 14, with each and every article devoted to the fictional Prince of Denmark and the play that bears his name. Rhodri Lewis asks “How Old is Hamlet?” while Samira Ahmed wonders “Why do Women Love Hamlet?” and we review recent productions of the play starring Tom Hiddleston and Andrew Scott. There's a set report from the making of Daisy Ridley's Ophelia movie and a visit to Hamlet's historic home, Kronborg Castle. We also delve deep into the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive's Hamlet collection, while Gyles Brandreth tells us about his family production of the play, and Alice Barclay recounts how she taught a group of amateur actors to become Hamlet.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

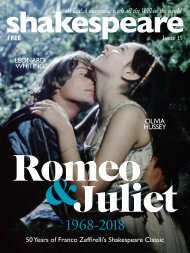

shakespeare<br />

At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world<br />

FREE<br />

Issue <strong>14</strong><br />

Who the<br />

Hell is<br />

Hamlet?

“...the readiness is all.” — Hamlet V.2<br />

Learn more at shakespeare300.com

Welcome <br />

Welcome<br />

Photo: David Hammonds<br />

to Issue <strong>14</strong> of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

When I decided to devote an entire issue of <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

to Hamlet, I assumed it would be a relatively straightforward process.<br />

After all, lots of people have lots of interesting things to say about this<br />

play and this character – all I had to do was fling it on the page.<br />

What I didn’t bargain for, but which in retrospect seems all too<br />

obviously predictable – is that in the process I would become Hamlet.<br />

I hesitated, I prevaricated, I dithered. I underthought things that<br />

required a good deal of thinking, and I overthought things that<br />

didn’t require any thinking at all. I prepared reams of interview<br />

questions, and them scrapped them. I wrote thousands of words and<br />

then chucked them in the bin. I remembered things – like the time<br />

I wrote and acted in a Hamlet spoof at school, over 30 years ago, in<br />

part inspired by an edgy production of the play that wowed me at<br />

Southport Arts Centre. And then I realised that some of my memories<br />

were no longer trustworthy.<br />

I think perhaps my main point here is that we all think we know<br />

Hamlet like we know ourselves. But when we return to the text(s) there<br />

are always shocks, surprises and rude awakenings in store.<br />

And just like Hamlet, my dithering at last ended, I suddenly knew<br />

what had to be done, and the issue finally rocketed to its conclusion.<br />

It’s been an education, and the bodies that litter this particular stage<br />

are, thankfully, all metaphorical. Anyway, here it is.<br />

Thanks as ever, for your patience and support.<br />

Enjoy your magazine.<br />

Pat Reid, Founder & Editor<br />

Donate to <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Donate here<br />

shakespeare magazine 3

At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world<br />

shakespeare<br />

FREE<br />

Issue <strong>14</strong><br />

Contents<br />

Who the<br />

Hell is<br />

Hamlet?<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Issue Fourteen<br />

July 2018<br />

Publisher<br />

JoAnn Markon<br />

Founder & Editor<br />

Pat Reid<br />

Art Editor<br />

Paul McIntyre<br />

Contributing Writers<br />

Samira Ahmed, Alice Barclay,<br />

Maddy Fry, Michael Goodman,<br />

Rhodri Lewis, Stewart Kenneth<br />

Moore, Clare Petre, Jen Richardson<br />

Photography<br />

Tim Gutt, Manuel Harlan,<br />

Jonathan Keenan, Francis Loney,<br />

Johan Persson, Bronwen Sharp,<br />

Julie Vrabelová<br />

Web Design<br />

David Hammonds<br />

Contact Us<br />

shakespearemag@outlook.com<br />

Facebook<br />

facebook.com/<strong>Shakespeare</strong><strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Twitter<br />

@UK<strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Website<br />

www.shakespearemagazine.com<br />

Newsletter<br />

http://tinyletter.com/shakespearemag<br />

Donate<br />

https://www.paypal.me/<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong><strong>Magazine</strong><br />

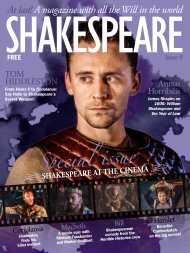

How Old is Hamlet? 6<br />

Hamlet is 30 years old – it says so in the text, right? Rhodri Lewis, author<br />

of Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness, explains why this is NOT the case.<br />

The Avenger<br />

Disassembled <strong>14</strong><br />

Maddy Fry savours the “intimacy<br />

and intensity” of Tom Hiddleston’s<br />

Hamlet at RADA.<br />

<br />

Soul-searching<br />

with Scott 20<br />

Clare Petre recounts the<br />

shatteringly cathartic experience<br />

of Andrew Scott’s Hamlet.<br />

<br />

4 SHAKESPEARE magazine

Contents <br />

Time Travelling<br />

with Ophelia 26<br />

<br />

<br />

Daisy Ridley’s Hamlet spin-off.<br />

<br />

Why do Women<br />

Love Hamlet? 32<br />

Samira Ahmed argues that there<br />

are “Three Ages of Hamlet” for the<br />

women fascinated by the Prince.<br />

<br />

Victorian Hamlet<br />

Illustration 38<br />

Michael Goodman picks his Hamlet<br />

favourites from the Victorian<br />

Illustrated <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Archive.<br />

<br />

How’s your<br />

Father? 48<br />

Jen Richardson meets Gyles<br />

<br />

family production of Hamlet.<br />

<br />

I Capture<br />

the Castle 56<br />

Pat Reid takes a trip to Denmark<br />

to visit Hamlet’s historic home, the<br />

mighty Kronborg Castle.<br />

<br />

Hamlet in the heat<br />

of the Night 60<br />

Alice Barclay makes Hamlet the<br />

people’s play on a sweltering<br />

summer’s evening in Bristol.<br />

<br />

SHAKESPEARE magazine 5

How Old is Hamlet?<br />

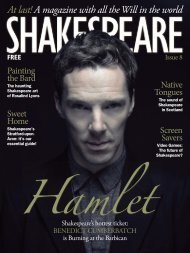

Artwork for<br />

the National<br />

Theatre’s 2015<br />

Hamlet (starring<br />

Benedict<br />

Cumberbatch)<br />

featuring the<br />

play’s characters<br />

as children.<br />

How Old is<br />

Hamlet?<br />

It’s a question every reader of Hamlet has found<br />

themselves asking. And one that Professor<br />

Rhodri Lewis has addressed in his recent major<br />

work Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness.<br />

6 shakespeare magazine

How Old is Hamlet? <br />

“In addition to its role in signifying mourning,<br />

black is also the academic colour”<br />

In writing Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness,<br />

one of the central planks of my argument<br />

is that Prince Hamlet is youthful and a<br />

university student. Approaching Hamlet<br />

– and Hamlet – from this perspective<br />

helped me to make a series of claims about<br />

what I take to be <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s attitudes<br />

to the humanistic doctrines of his era<br />

(Hamlet never stops grappling with, and<br />

can never quite escape from, the “saws<br />

and observations” of his Wittenberg education),<br />

and about how <strong>Shakespeare</strong> uses his dramatic art<br />

both to critique them and to move beyond them.<br />

Hamlet’s youth also offers a plausible explanation<br />

for the decision of the Danish court to elect<br />

Claudius its monarch in succession to Old Hamlet:<br />

Hamlet is on the way to full manhood, but is not<br />

there yet. Claudius kills Old Hamlet shortly after<br />

Hamlet has left Denmark for the new academic<br />

year in Wittenberg, juxtaposing his presence (in<br />

all senses of the term) with his nephew’s absence.<br />

“Young Hamlet” is still learning about himself and<br />

the world around him; his time will come.<br />

A peculiarity of writing books for university<br />

presses is the process of peer review. Your<br />

manuscript is handed by the press to two or<br />

perhaps three anonymous experts, who then<br />

write reports in which they submit your work to<br />

thoroughgoing scrutiny. Even when agreeing in<br />

their recommendations (from “publish as it stands”<br />

to “over my dead body”), these reports frequently<br />

differ so much from one another that you can begin<br />

to doubt whether their writers were reading the<br />

same things; as an author, the best you can hope<br />

for is that what you’ve written will be approached<br />

intelligently and with an open mind.<br />

One of the few topics on which the anonymous<br />

reviewers of my manuscript agreed with each other<br />

was that as I had made a lot of Hamlet’s youth<br />

and student status, I couldn’t sidestep the fact<br />

that, in the Graveyard scene, we are told pretty<br />

unambiguously that he is thirty. So it was that I<br />

decided to write an appendix tackling the question<br />

of exactly how old Hamlet is supposed to be.<br />

Writing it turned out to be more difficult, more<br />

interesting, and much more enjoyable than I had<br />

anticipated: the action of the play not only enables<br />

us to say some concrete things about Hamlet’s<br />

age, but also allows us to witness <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

engagement with what, in the years around 1600,<br />

was the new language of numbers. Familiar though<br />

Hamlet is to all of us, and voluminous though the<br />

literature on it has become, writing my book led<br />

me to the conclusion that we have only begun to<br />

scratch the surface.<br />

Hamlet is described on several occasions as<br />

“young”; he is roughly the same age as Fortinbras,<br />

Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern; he seems to be<br />

a little younger than Horatio and Laertes; he is a<br />

student at Wittenberg; he thinks and speaks like<br />

one in the midst of a humanistic education. And yet<br />

his exchange with the Gravedigger at the beginning<br />

of Act 5 appears, anomalously but unambiguously,<br />

to suggest that he is thirty years old. However, the<br />

age given in the graveyard scene does not stand<br />

up to scrutiny: it emerges from a textual crux, is<br />

at variance with the manifest signs of Hamlet’s<br />

age given elsewhere in the play, and relies on an<br />

authority – the Gravedigger – whose arithmetical<br />

skills are very much open to question. I also suggest<br />

that thinking about Hamlet’s age in terms of the<br />

number of years he might have been on the earth is<br />

misconceived.<br />

After satisfying himself that the Ghost is not<br />

purely a figment of Marcellus and Barnardo’s<br />

imaginations, Horatio decrees that they should<br />

impart what they “have seen tonight / Unto<br />

young Hamlet” (1.1.174-75). “Young” here<br />

differentiates the son from his father: deutero-<br />

Hamlet, Hamlet Junior, Hamlet the Younger. But<br />

it is also the adjective with which <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

chooses to introduce his disaffected prince, and<br />

reveals something not only about his royal status<br />

but about his quality of being. Versions of it<br />

reappear frequently throughout the play. Claudius<br />

counsels Hamlet that his enduring display of grief<br />

shakespeare magazine 7

How Old is Hamlet?<br />

“Hamlet’s desire to return to his studies at<br />

Wittenberg tells us that he is a teenager”<br />

Benedict<br />

Cumberbatch<br />

played the role<br />

of Hamlet at<br />

the age of 39,<br />

having just<br />

become a<br />

father for the<br />

<br />

for his father is “unmanly” (1.2.84), a term that is<br />

normative rather descriptive, but whose persuasive<br />

force depends on Hamlet aspiring to, rather than<br />

already having attained, the condition of manliness;<br />

Laertes thinks of Hamlet as “A violet in the youth of<br />

primy nature” (1.3.7); the Ghost tells Hamlet that<br />

if it were to describe the afterlife in detail, the effect<br />

would be to “freeze thy young blood” (1.5.16), and<br />

addresses him as a “noble youth” (1.5.38); Claudius<br />

turns to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern because<br />

they are “of so young days brought up with him, /<br />

And with so neighbour’d to his youth and haviour”<br />

(2.2.11-12); the fencing match between Hamlet<br />

and “young Laertes” (4.5.101; cf. 5.1.217) is framed<br />

with some care as a contest of “youth” (4.7.72-80).<br />

One might go on, but the point is incontestable:<br />

although it might be possible to dispute what<br />

“young” is intended to signify in the dramatic<br />

context of Hamlet, it definitively connotes more<br />

than Hamlet’s status as the son of a father with the<br />

same name. Before he has taken on the part of the<br />

forensic huntsman, tracking and seeking to expose<br />

his uncle’s guilt, Hamlet himself acknowledges his<br />

resemblance to a “rascal”, or juvenile deer (2.2.562).<br />

On the basis that Hamlet and Fortinbras are<br />

so obviously set in counterpoint to one another,<br />

to say nothing of the fact Fortinbras’s father was<br />

killed on the day Hamlet was born (5.1.139-40), we<br />

can surmise that Hamlet is about the same age as<br />

Fortinbras; either a little older than him, or a little<br />

younger. If the former, then no more than nine<br />

months so. As the frustrated son of an overthrown<br />

monarch, Hamlet sees his own character<br />

illuminated by the bold example of his Norwegian<br />

peer. So much so that his final soliloquy projects<br />

his own likeness onto this would-be conqueror<br />

of Denmark, envisaging him as “a delicate and<br />

tender prince” (4.4.48); Fortinbras will return the<br />

compliment by imagining the dead Hamlet as a<br />

soldier. In fact, their tender years are all they have<br />

in common.<br />

Hamlet’s status as a student further asserts his<br />

8 shakespeare magazine

How Old is Hamlet? <br />

youthfulness. Lawrence Stone’s statistical labours<br />

give a clear picture of when it was that early modern<br />

Englishmen went to university. For instance, the<br />

median age of matriculation at Oxford for the<br />

years 1600-02 was 17.1. Among the aristocracy<br />

and gentry it was substantially lower, at 15.9 years.<br />

Further, it was common for the well-educated<br />

sons of socially elevated families to enter university<br />

as young as eleven or twelve. A good example is<br />

Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton and<br />

the dedicatee of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Venus and Adonis<br />

and Lucrece. Wriothesley went up to St. John’s<br />

College, Cambridge in 1585 at the age of twelve;<br />

he graduated before he turned sixteen in 1589, at<br />

which point he had already been admitted to Gray’s<br />

Inn. In a word, Hamlet’s desire to return to his<br />

studies at Wittenberg tells us that he is a teenager.<br />

To an audience of theatregoers or readers in late<br />

Elizabethan or early Jacobean London, it would<br />

have been starkly irregular for an aristocrat, let<br />

alone a member of the royalty, to have remained at<br />

university beyond the age of about twenty.<br />

Hamlet’s ambitious but frequently confused and<br />

incoherent mode of discourse sounds like that of<br />

an early modern university student. But as Barbara<br />

Everett has proposed, it might well be that he also<br />

looks like a student, or at least that he did so to<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s earliest audiences: in addition to its<br />

role in signifying mourning, black is the academic<br />

colour.<br />

We come now to the encounter between Hamlet<br />

and the Gravedigger. Hamlet asks the Gravedigger<br />

when he began digging graves, and the following<br />

exchange ensues:<br />

Gravedigger: Of all the days i’th’ year I cam to’t that<br />

day that our Last King Hamlet o’ercame Fortinbras.<br />

Hamlet: How long is that since?<br />

Gravedigger: Cannot you tell that? Every fool can<br />

tell that. It was that very day that young Hamlet<br />

was born – he that is mad and sent into England.<br />

(5.1.139-44)<br />

From which we deduce that although the<br />

Gravedigger thinks that “every fool” knows when<br />

Old Hamlet defeated Old Fortinbras and Hamlet<br />

was born, Hamlet himself is less sure. After several<br />

lines in which the Gravedigger works hard to evade<br />

the questions he has been asked by and about<br />

“young Hamlet”, he steers the conversation back to<br />

the ground beneath their feet:<br />

Gravedigger: I have been sexton here, man and boy,<br />

thirty years.<br />

Hamlet: How long will a man lie i’th’ earth ere he<br />

rot?<br />

Gravedigger: Faith, if a be not rotten before a die<br />

... a will last you some eight year or nine year.<br />

(5.1.156-62).<br />

On the face of it, this is open and shut. The<br />

gravedigger has been at his trade (i.e., a sexton) for<br />

thirty years. Hamlet is therefore thirty years old,<br />

however out of keeping that might seem with the<br />

rest of the play. There are, however, both textual and<br />

interpretative grounds to doubt this reading, and to<br />

stick with our inference that Hamlet the student is a<br />

teenager.<br />

The textual crux first. As many readers of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> will be aware, there are<br />

two authoritative versions of the play. One is the<br />

1604/05 Second Quarto (Q2), the other is the<br />

1623 First Folio. Only Q2 supports the reading of<br />

the text given above. On the question of how long<br />

the Gravedigger had been at his work in Denmark,<br />

the Folio (TLN 3351-52) has him say “I have<br />

been sixeteene heere, man and Boy thirty yeares”.<br />

The reading is grammatically challenging, but<br />

offers a very different picture of Hamlet’s age. The<br />

Gravedigger has been “heere” (qua Denmark and/<br />

or his graveyard – he is being willfully ambiguous)<br />

for sixteen years, and has been “man and Boy thirty<br />

yeares”. On this account, it is the Gravedigger who<br />

is thirty years old, while Hamlet is only sixteen.<br />

Q2 has traditionally been preferred, on account<br />

both of its grammatical simplicity and of what the<br />

Gravedigger reveals about a disarticulated skull that<br />

has caught his attention: “Here’s a skull now hath<br />

lien you i’th’ earth three and twenty years” (5.1.166-<br />

68). On being pressed, the Gravedigger discloses<br />

that “This same skull, sir, was Yorick’s skull, the<br />

King’s jester” (5.1.175-77). As Hamlet goes on to<br />

recall the joyful times he had spent with Yorick as a<br />

child and as Yorick died twenty-three years ago, the<br />

textual logic runs smoothly: Hamlet must be thirty<br />

years old, and the Folio reading a corruption of Q2,<br />

which spells sexton “sexten”. The more so because<br />

the thirty years of Hamlet’s life echo the thirty years<br />

shakespeare magazine 9

How Old is Hamlet?<br />

Left: Naeem Hayat, one of the young<br />

actors who portrayed Hamlet in the<br />

epic Globe to Globe production.<br />

Right: Maxine Peake’s Hamlet was<br />

full of adolescent energy – although<br />

she was aged 40 at the time.<br />

that the Player King and Queen have been married<br />

(3.2.150-55). Even “unedited” texts of Hamlet<br />

based on the Folio emend it.<br />

If one sticks with the mortal remains of Yorick,<br />

things quickly become more complicated. Putting<br />

to one side the question of why the Gravedigger has<br />

unearthed his skull (has it been dug up accidentally<br />

or on purpose? Where is the rest of him? And how,<br />

with human remains apparently littered around<br />

him, can he be sure that the skull in question<br />

belonged to Yorick?), a twenty-three-year-old corpse<br />

should on the Gravedigger’s own account long ago<br />

have become a skeleton: it has been in the ground<br />

for fourteen or fifteen years more than the eight<br />

or nine he specifies for complete decomposition.<br />

And yet, Yorick’s skull has the rankly sweet odour<br />

of human decay. “My gorge rises at it” (5.1.181-82)<br />

might just about be understood as an expression of<br />

metaphysical nausea at handling the skull beneath<br />

the skin of a loved one, but the gross physicality of<br />

the matter is soon beyond doubt:<br />

Hamlet: Prithee, Horatio, tell me one thing.<br />

Horatio: What’s that, my lord?<br />

Hamlet: Dost thou think Alexander looked o’ this<br />

fashion i’th’ earth?<br />

Horatio: E’en so.<br />

Hamlet: And smelt so? Pah!<br />

Horatio: E’en so, my lord. (5.1.189-95)<br />

This is a graveyard, not a charnel house in which<br />

the stink of a newly decomposing corpse might<br />

taint even the most desiccated bones. Yorick’s soft<br />

tissue has not yet fully putrefied. His body has been<br />

in the ground for nothing like as long as twentythree<br />

years.<br />

Before going any further, I want briefly to glance<br />

at the 1603 First Quarto (Q1) of the play. By virtue<br />

of so straightforwardly making both numerical<br />

and dramatic sense, it hints at something integral<br />

about the puzzles of Hamlet’s age and Yorick’s<br />

subterranean years in Q2 and the Folio. In Q1, the<br />

Gravedigger brandishes a skull:<br />

10 shakespeare magazine

How Old is Hamlet? <br />

“The Earl of Southampton attended Cambridge<br />

at the age of 12, and graduated at 15”<br />

Look you, here’s a skull hath been here this dozen<br />

year – let me see, ay, ever since our last King Hamlet<br />

slew Fortenbrasse in combat – young Hamlet’s<br />

father, he that’s mad.<br />

The Gravedigger subsequently reveals that<br />

the skull belonged to Yorick; Hamlet laments the<br />

dead clown and the transitoriness of life, then<br />

recoils from the skull’s smell. There is no mention<br />

of Hamlet’s age (the problem of which is thereby<br />

resolved), and granting that “dozen” need only<br />

be the reflexively imprecise unit of measurement<br />

of one brought up in the duodecimal thinking of<br />

English tradition, there is no difficulty with Yorick’s<br />

skull still reeking of putrefaction. As these remarks<br />

imply, I take it that the textual discrepancies of<br />

Q1 are, as usual, those of simplification. Whoever<br />

was responsible for Q1 and however he or they<br />

produced it, the text fails to grasp that numerical<br />

incoherence is the point of Hamlet’s exchange with<br />

the Gravedigger.<br />

This incoherence has its root in <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

awareness that the cultures of early modern England<br />

and Europe were not arithmetically advanced.<br />

Although arithmetic belonged to the quadrivium,<br />

facility in mental arithmetic (“reckoning”) was<br />

confined to merchants, sailors, soldiers, and other<br />

more or less artisanal trades. For the general<br />

populace, of high and low social status alike, the<br />

ability to compute more than the most elementary<br />

sums of addition and subtraction depended on the<br />

manipulation of physical counters on a board, and<br />

recording the results in Roman numerals. And yet<br />

at the same time, the impulse to exact measurement<br />

and quantification, and with it Arabic numerals,<br />

had already begun its transformation of western<br />

intellectual life. The dramatic potential of this state<br />

of affairs had long since been exploited by Marlowe<br />

(who frequently has his characters grasp at numbers<br />

in the ineffectual effort to show themselves in<br />

control of a situation), and <strong>Shakespeare</strong> was not<br />

slow to turn it to his own ends. As Edward Wilson-<br />

Lee has shown, he did so sustainedly in Troilus and<br />

Cressida. But perhaps the most obvious place to<br />

look in establishing this claim is The Winter’s Tale –<br />

where much is made of the discrepancy between the<br />

apparent precision of numeration and the vagueness<br />

with which numbers are, in reality, employed. A<br />

Clown enters, destined to be swindled by Autolycus.<br />

The Clown is attempting to figure out the value of<br />

the wool he has shorn from his 1500 sheep, but has<br />

to give up: “I cannot do’t without counters”. Like<br />

any good cony-catcher, Autolycus is as astute as<br />

he is opportunistic. He does not share the Clown’s<br />

difficulties, and sets to work on his mark.<br />

The exchange between Hamlet and the<br />

Gravedigger is animated by exactly the same<br />

cultural dynamics. Both characters enjoy feeling like<br />

the cleverest person in any conversation; both will<br />

say anything to ensure that they get to feel like this;<br />

in the culminating skirmish of their wits, neither<br />

shows more than the most rudimentary notion of<br />

how to compute numbers in general, or of how to<br />

use numbers to compute time in particular.<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> quickly establishes that the<br />

Gravedigger, like Dogberry, is prone to detach<br />

verba from res for self-aggrandising rhetorical<br />

effect. In describing the prospect of Ophelia having<br />

drowned herself in self-defence, he asserts to his less<br />

loquacious partner that “It must be se offendendo”<br />

(5.1.9). He means the opposite (i.e., se defendendo),<br />

but the chance to accrue some Latinate cultural<br />

capital is too good to miss. A little later, he theorises<br />

that if a man goes to the water, “but the water come<br />

to him and drown him, he drowns not himself.<br />

Argal, he that is not guilty of his own death shortens<br />

not his own life” (5.2.18-20). For “argal”, he means<br />

to say ergo; he again seeks to repeat a Latin word<br />

that he has heard others use to impressive effect, but<br />

that he does not himself understand.<br />

Once Hamlet and Horatio arrive in the<br />

graveyard, Hamlet begins to speculate about the<br />

various disreputable parts that the people whose<br />

skulls are before them might formerly have played<br />

(“here’s fine revolution”). He and the Gravedigger<br />

then engage in some mutual chicanery about lying,<br />

lying down, and the business of digging graves. The<br />

shakespeare magazine 11

“Adolescence is an age of apprenticeship in the<br />

world, of preparation for the challenges ahead”<br />

Gravedigger considers answering direct questions<br />

to be dull or otherwise beneath him. Hamlet sees<br />

his answers as a sort of “equivocation”, and informs<br />

Horatio that “these three years I have took note<br />

of it, the age is grown so picked [i.e. pernickety,<br />

nit-picking] that the toe of the peasant comes so<br />

near the heel of the courtier that he galls his kibe”<br />

(5.1.135-38); the sophistry of the lower orders is<br />

snapping at the heels of the nobility. Quite aside<br />

from the fact that Hamlet has spent most of the<br />

last year or two (or three) away from Elsinore<br />

as a student at Wittenberg, the most important<br />

aspect of this declaration is that his “three years” is<br />

meaningless as anything other than a placeholder<br />

for “of late” or “in recent history”. It operates on the<br />

same level as the “he walks for four hours together”<br />

(i.e., for long periods of time) that Polonius observes<br />

of Hamlet at 2.2.160, or Hamlet’s own assertion<br />

that not even “Two thousand souls and twenty<br />

thousand ducats” (i.e., a vast accumulation of<br />

manpower and money) would be enough to “debate<br />

the question of this straw” between Fortinbras and<br />

“the Polack” (4.4.25-26). “Three years” nevertheless<br />

has the feel of considered observation, and leads<br />

Hamlet to ask the Gravedigger how long he has<br />

been about his business. The Gravedigger seems<br />

no keener to answer this question than those that<br />

preceded it, but his response is historically specific:<br />

since the day on which Old Hamlet defeated Old<br />

Fortinbras and the younger Hamlet was born.<br />

Remarkably, even for one who has trouble<br />

reckoning with numbers, Hamlet shows no sign<br />

of being able to quantify when his father’s famous<br />

victory took place. Furthermore, the Gravedigger<br />

asserts that “every fool” knows this event to have<br />

been synchronous with Hamlet’s birth, and it<br />

beggars belief to suppose that Hamlet has never<br />

heard of this synchroneity for himself – especially as<br />

it makes his royal birth, like his royal patronymic,<br />

seem distinctly auspicious. The conclusion? Hamlet<br />

does not know how old he is. He immediately<br />

changes the subject when the Gravedigger’s<br />

comments threaten to lay this reality bare. The<br />

Gravedigger may or may not suspect that his highborn<br />

interlocutor is, in fact, the “young Hamlet”<br />

of whom he is now being pushed to speak, but<br />

must sense that the drift of their conversation<br />

towards matters of state puts him in danger. He<br />

needs to tread carefully, and once he guesses that his<br />

questioner has a limited facility with numbers, sees<br />

a gratifying way out. His gambit succeeds: unable to<br />

fathom what the Gravedigger says about his age and<br />

the duration of career, Hamlet counter-bluffs with<br />

a question about rates of bodily decay. From there,<br />

the Gravedigger – aided by the skull of Yorick (if,<br />

indeed, it is the skull of Yorick) – has no difficulty<br />

in redirecting their discussion to safer territory; in<br />

this case, to the conditions of mortality. In dwelling<br />

on Yorick and then discovering the death of<br />

Ophelia, Hamlet lets numbers go, but soon returns<br />

to them in belittling the “dozy arithmetic” of Osric’s<br />

memory. (As he does in claiming to understand<br />

the “odds” on his fencing match with Laertes.)<br />

The rub is that the Gravedigger is no better at the<br />

numerical computation of time than he is at Latin.<br />

His historical measurements of sixteen, thirty, and<br />

twenty-three years are empty signifiers – no more<br />

than words. They are self-contradictory, but he<br />

doesn’t care: he gets to put one over on someone<br />

of a far higher social and educational status than<br />

himself, and who has presumed to question his<br />

work.<br />

So, the numbers in the graveyard scene as<br />

recorded in Q2 and the Folio designedly do not<br />

compute. They represent the inability of Hamlet<br />

and of the Gravedigger to reckon with historical<br />

numbers in their heads, and the desire of both<br />

characters to look as if they can. Both “sexten/<br />

sexton” (Q2) and “sixeteene” (the Folio) lend<br />

themselves to the incongruity of what follows (the<br />

more so as “sexten heere” and “sixteene yeare” are<br />

likely to have been all but homophonic in early<br />

modern English), but “sixeteene” seems to me the<br />

better reading. In clashing so directly with the<br />

twenty-three years that Yorick is supposed to have<br />

been in the ground, it allows the exchange to make<br />

even less sense, thereby capturing more of the<br />

Gravedigger’s pretentions and self-regard, and of<br />

12 shakespeare magazine

In his midtwenties,<br />

Paapa Essiedu<br />

(pictured<br />

here in the<br />

Gravedigger<br />

scene) was a<br />

boyish-looking<br />

Hamlet for the<br />

RSC (2016-18).<br />

Hamlet’s inability to expose them. Folio “sixteene”<br />

as a corruption of Q2 “sexten” cannot be ruled<br />

out, but nor can the possibility that just as Q2<br />

stumbles over the nonsensical se offendendo, so it<br />

sees that sixteen (howsoever spelled) is contradicted<br />

by the reported death of Yorick, and emends it to<br />

“sexten”. On one level, a far from unreasonable<br />

procedure. Unfortunately, to convey the impression<br />

of nonsense is precisely <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s point: Hamlet<br />

and the Gravedigger only feign to know what they<br />

are talking about. Their attempts to speak the new<br />

language of numbers offer a comically macabre<br />

miniature of the pretence, and frequent bravado,<br />

that drives life in Elsinore as a whole. Ever the<br />

radical egalitarian, <strong>Shakespeare</strong> reminds us that<br />

the willingness to mislead does not belong to the<br />

socially elevated orders alone; Denmark’s afflictions<br />

cannot be explained by looking in isolation at the<br />

vices, or even the crimes, of those who rule it.<br />

What does all of this tell us about Hamlet’s age?<br />

As his student status suggests, he is an adolescent.<br />

That is, an inhabitant of the intermediate category<br />

between boyhood and the assumption of adult<br />

masculinity; on the seven-stage model of human life<br />

familiar to <strong>Shakespeare</strong>, the period between one’s<br />

fourteenth and twenty-first birthdays. To venture<br />

anything more precise is guesswork or special<br />

pleading, and to maintain that he is thirty – perhaps<br />

with reference to the age of Richard Burbage when<br />

he played him for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men –<br />

is unsustainable. In As You Like It, Jaques portrays<br />

adolescence as the age of “the lover, / Sighing<br />

like a furnace, with a woeful ballad / Made to his<br />

mistress’ eyebrow”, and his depiction maps well<br />

onto Hamlet’s relationship with Ophelia – before<br />

and after she jilts him. But in most iterations,<br />

adolescence has a different aspect. It is an age of<br />

apprenticeship in the world, of preparation for the<br />

challenges ahead, and of fitting one’s understanding<br />

to one’s burgeoning physical and sexual potency;<br />

it is also marked by heat, impetuousness, and<br />

impatience. Ecce homo.<br />

<br />

Hamlet and the<br />

Vision of Darkness<br />

is published<br />

by Princeton<br />

University Press<br />

Buy it here<br />

shakespeare magazine 13

Tom Hiddleston<br />

“Revenge is a fool’s errand,it gets you nothing.<br />

And Hamlet is really about that.The interesting<br />

thing about playing Hamlet is that as an actor<br />

one is so aware of the size of the play and the<br />

significance of the role… And then when you<br />

approach playing it, you have to meet the play<br />

head on and confront it.”<br />

Tom Hiddleston, speaking to Jenelle Riley for Variety<br />

<strong>14</strong> shakespeare magazine

Tom Hiddleston <br />

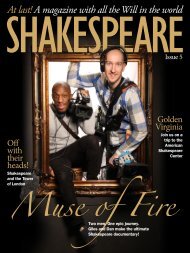

Left: Hamlet (Tom Hiddleston).<br />

Below: Guildastern (Eleanor de Rohan), Horatia<br />

(Caroline Martin), Hamlet (Tom Hiddleston)<br />

Rosencrantz (Ayesha Antoine).<br />

The Avenger<br />

Disassembled<br />

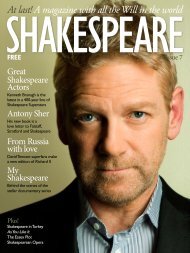

If you were one of those lucky enough to get a<br />

ticket, director Kenneth Branagh’s massively<br />

over-subscribed RADA Hamlet starring Tom<br />

Hiddleston was all about the “intimacy and<br />

<br />

Words by Maddy Fry<br />

Photos by Johan Persson<br />

shakespeare magazine 15

Tom Hiddleston<br />

Left: Tom Hiddleston as Hamlet and<br />

Caroline Martin as Horatia.<br />

Above: Hamlet and King Claudius<br />

(Nicholas Farrell).<br />

Right: Hamlet battles Laertes (Irfan<br />

Shamji).<br />

Often I’ve found it comforting that<br />

most of Tom Hiddleston’s alter-egos<br />

seem incapable of making good<br />

choices. Whether it’s the PTSDinspired<br />

alcoholism of Freddie<br />

Page in The Deep Blue Sea or the <strong>Shakespeare</strong>an<br />

sibling angst of the Marvel villain Loki, most of his<br />

characters are dogged by despair and failure. Even<br />

the nefarious Prince Hal of The Hollow Crown and<br />

the enigmatic Jonathan Pine at the centre of The<br />

Night Manager go through considerable travails<br />

before fulfilling their true purpose. It seemed apt<br />

that director Kenneth Branagh described the Prince<br />

of Denmark, that great monument to unfulfilled<br />

ambition, as “the role he was born to play.”<br />

For any devotee of Hiddleston, the chance to<br />

see him as Hamlet in a tiny central London theatre,<br />

nestled within the walls of his old drama school,<br />

felt akin to seeing The Beatles at the Cavern Club<br />

– the sense of a colossal talent scaled down while<br />

losing none of its potency. The result was little<br />

short of magical.<br />

Up close and personal in RADA’s 160-seat<br />

auditorium, the play opened with Hamlet sitting<br />

in near-darkness at the piano, crooning out a low<br />

wolf-howl of defeat.<br />

“And will he not come again?” our hero<br />

moaned, lamenting the absence of his father via the<br />

heart-wrenching cadence of “No, no he is dead. Go<br />

to thy deathbed...”<br />

Hamlet’s alienation and sense of betrayal over<br />

his mother’s hasty remarriage was, particularly for<br />

16 shakespeare magazine

Tom Hiddleston <br />

those in the front row, frighteningly visceral, made<br />

manifest through kicking and screaming, spit,<br />

sweat and tears. In turn, Hiddleston masterfully<br />

depicted Hamlet’s inability to be what those<br />

around him needed – supportive, vengeful, loving,<br />

or even just consistent.<br />

Much has been made of how HiddleHamlet’s<br />

madness was undoubtedly feigned, yet the<br />

production’s great strength was the ease with<br />

which he switched to an all-too-real malice and<br />

vindictiveness. His brushing aside of Ophelia<br />

(Kathryn Wilder), triggering her fatal sense of<br />

abandonment, combined with his shrugging off the<br />

deaths of his informant friends, were shocking in<br />

their callousness.<br />

Yet one couldn’t shake the feeling that the<br />

derangement and loss of control in Hamlet’s eyes<br />

after murdering Polonius (Sean Foley) was genuine.<br />

The final duel resulting in the Prince’s death, barely<br />

two feet from my seat, was no less agonising for its<br />

portrayal of one man imprisoned by grief, with its<br />

destructive effects spiralling outwards.<br />

“More than anything, this Hamlet was about<br />

bereavement and family breakdown”<br />

shakespeare magazine 17

Tom Hiddleston<br />

“Hamlet’s alienation and sense of betrayal over his<br />

mother’s remarriage was frighteningly visceral”<br />

Above: The Ghost of Hamlet’s father, King<br />

Hamlet (Ansu Kabia).<br />

Right: Hamlet’s mother, Queen Gertrude<br />

(Lolita Chakrabarti).<br />

The threat of military conquest by Norway always<br />

hung in the foreground, but more than anything<br />

this Hamlet was about bereavement and family<br />

breakdown – the torment caused by our relatives<br />

moving on, even if we can’t, and robbing us of<br />

any space to heal. Proof, as though it were needed,<br />

that <strong>Shakespeare</strong> speaks to us for the moment we<br />

find ourselves in. Few plays have left me waking<br />

up sobbing the next day, but the rage, remorse and<br />

anguish on display still resonated, to the refrain<br />

throughout of “Go to thy deathbed...”<br />

Yet on the night, for those in attendance it was<br />

three hours of uncomplicated happiness. Watching<br />

Hiddleston seamlessly recite ‘To be, or not to be’<br />

right in front of me was enough to make me feel<br />

thankful for my pulse. As much as I loved Benedict<br />

Cumberbatch’s 2015 turn at the Barbican, it<br />

couldn’t rival RADA’s Hamlet for intimacy and<br />

intensity of craftsmanship.<br />

<br />

This performance of Hamlet took place<br />

on 20 September 2017 at the Jerwood<br />

Vanbrugh Theatre, London<br />

18 shakespeare magazine

UpstartCrowCreations Presents...<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Plot Device Dice<br />

Available from<br />

ETSY<br />

AMAZON<br />

Will it be shipwrecked twins visited by the ghost of their<br />

bewitched father? Star-crossed lovers who vie for the throne but<br />

exit pursued by bears? Cross-dressing shrews beset by fairies and<br />

fools? Only the dice can tell you, and only YOU can tell the story!<br />

Game includes: Five generously sized wooden dice (one for each<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>an act), suggested storytelling instructions, and a<br />

drawstring pouch to hold your devices when you’re not plotting.<br />

Number of players: 2-10+<br />

Dice are 1.18” x 1.18” —ink and lacquer on Beechwood.<br />

Suitable for ages: 8+<br />

Ideal for storytellers, role players, teaching artists,<br />

theatre practitioners, and rabid Bardophiles!<br />

Need info before you plot?<br />

Write to: UpstartCrowCreations@gmail.com

Andrew Scott<br />

“With Hamlet… we mourn<br />

our own tragedies as they are<br />

reflected on the stage”<br />

SOUL-SEARCHING<br />

20 shakespeare magazine

Andrew Scott <br />

Behind the sofa:<br />

Andrew Scott’s Hamlet<br />

had a watchful quality,<br />

in a production where<br />

surveillance technology<br />

was given a notable<br />

supporting role.<br />

WITH SCOTT<br />

Irish actor Andrew Scott delivered an<br />

“exquisite, fragile” performance in Robert<br />

Icke’s “electrifying, heart-wrenching<br />

production” of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s Hamlet at<br />

London’s Harold Pinter Theatre.<br />

Words: Clare Petre Photos: Manuel Harlan<br />

shakespeare magazine 21

Andrew Scott<br />

“Laertes became a man torn between his loyalty<br />

to the court and his desire to forgive Hamlet”<br />

Gertrude (Juliet<br />

Stevenson)<br />

attempts<br />

to restrain<br />

Laertes (Luke<br />

Thompson).<br />

irector Robert Icke’s exceptional<br />

contemporary interpretation of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

most famous play has had plenty of time to<br />

sit. Indeed, London has seen two further Hamlets<br />

(Tom Hiddleston’s and Benet Brandreth’s) since<br />

this formidable piece of theatre closed, but Andrew<br />

Scott’s is the one that seems to haunt the capital.<br />

With its soundtrack of some of Bob Dylan’s most<br />

touching songs, this electrifying, heart-wrenching<br />

production has plunged a poisoned foil into the<br />

hearts of thousands.<br />

Andrew Scott’s exquisite, fragile Hamlet was<br />

offset beautifully by Jessica Brown-Findlay’s<br />

graceful yet physically strong Ophelia (her dance<br />

background was evident throughout), whose<br />

weakness, ironically, lay in her attempting to<br />

convince herself and the court of her strength.<br />

I have seen criticism of the “monotony” of<br />

Angus Wright’s Claudius, as if his performance left<br />

something to be desired. I disagree – Wright is an<br />

accomplished actor and his Claudius was cunningly<br />

crafted. He left us in no doubt as to how Derbhle<br />

Crotty’s elegant and likeable Gertrude, in the midst<br />

of her confusion and grief, was attracted to his<br />

lupine, prowling figure but saw the error of her<br />

ways so quickly in the closet scene.<br />

Peter Wight’s Polonius was apparently<br />

succumbing to the insidious effects of dementia,<br />

22 shakespeare magazine

Andrew Scott <br />

but his performance lost none of the character’s<br />

levity.<br />

Aided by a cast of such strength, the play felt<br />

so fresh that some of its most famous and often<br />

most laboured words became unfamiliar. Icke’s<br />

daring direction served to emphasise this by giving<br />

several of the play’s best-known moments entirely<br />

new readings. Laertes’ plea to use another foil, as<br />

the one he has chosen is “too heavy”, for example,<br />

became a sudden second thought – a desperate and<br />

urgent cry to avoid the inevitable, and perhaps use<br />

a foil untainted with poison. He became a man<br />

torn between his loyalty to the court, and his desire<br />

to forgive Hamlet and begin to define a better<br />

future. For the duel scene itself, <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s<br />

words were all but abandoned, the fight performed<br />

as a dumb-show to Bob Dylan’s ‘Not Dark Yet’.<br />

Emotionally manipulative? Perhaps. Facile?<br />

Possibly. Heart-breaking? Undeniably.<br />

This production’s outstanding competence lay<br />

in giving its audience the opportunity to share<br />

grief and express its own, usually muted, sorrows.<br />

Shared emotion equates to shared humanity. As a<br />

fully paid-up member of Generation X, I cannot<br />

remember a more (over)dramatic outpouring of<br />

love and grief than that which we witnessed after<br />

Hamlet’s brooding isolation is neatly updated and encapsulated in this scene.<br />

shakespeare magazine 23

Andrew Scott <br />

“Angus Wright is an accomplished actor, his<br />

lupine, prowling Claudius is cunningly crafted”<br />

Barry Aird as the<br />

play’s infamously<br />

irreverent<br />

Gravedigger.<br />

Awkwardly<br />

positioned between<br />

Claudius and<br />

Gertrude, Hamlet<br />

is forced to smile<br />

for the cameras.<br />

the death of Princess Diana, which has been much<br />

discussed of late, it being the 20th anniversary<br />

of the Paris crash. There was, at the time, an<br />

extraordinary and tribal response to her carefully<br />

orchestrated funeral.<br />

With Diana, we were not mourning the<br />

death of a princess so much as celebrating the<br />

opportunity to experience human communality.<br />

So with Hamlet, while we feel acutely his pain,<br />

Ophelia’s, Gertrude’s, we mourn our own tragedies<br />

as they are reflected upon the stage. When we<br />

weep for Hamlet and his fellow characters, we are<br />

weeping for our own grief and for the sense of loss<br />

which might permeate our own lives, but using<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s writing as a conduit. To paraphrase<br />

Gertrude, this Elsinore turned our eyes into our<br />

very souls.<br />

I fell in love with Hamlet 30 years ago, and<br />

in that time many interpretations have come and<br />

gone. But it is Andrew Scott’s that has remained<br />

with me above all others, and which will do until<br />

usurped. I suspect I am in for a long wait.<br />

<br />

This performance of Hamlet took place on Monday<br />

24 July 2017 at the Harold Pinter Theatre, London,<br />

with Derbhle Crotty in the role of Gertrude.<br />

24 shakespeare magazine

Planning to perform<br />

a short selection<br />

from <strong>Shakespeare</strong>?<br />

The 30-Minute <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Anthology contains 18 abridged<br />

scenes, including monologues, from<br />

18 of <strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s best-known plays.<br />

Every scene features interpretive stage<br />

directions and detailed performance<br />

and monologue notes, all “road tested”<br />

at the Folger <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Library’s<br />

annual Student <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Festival.<br />

<br />

“Lays the groundwork for a truly fun and sometimes magical<br />

experience, guided by a sagacious, knowledgeable, and intuitive<br />

educator. Newlin is a staunch advocate for students learning<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong> through performance.” —Library Journal<br />

The 30-Minute <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Anthology<br />

includes one scene with monologue<br />

from each of these plays:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

THE 30-MINUTE SHAKESPEARE is an acclaimed series of abridgments that tell the story of each play while keeping the beauty of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s language intact. The scenes and monologues in this anthology have been selected with both teachers and students in<br />

mind, providing a complete toolkit for an unforgettable performance, audition, or competition.<br />

NICK NEWLIN has performed a comedy and variety act for international audiences for more than 30 years. Since 1996, he has<br />

conducted an annual teaching artist residency with the Folger <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Library in Washington, D.C.<br />

The 30-Minute <strong>Shakespeare</strong> series is available in print and ebook format at retailers<br />

and as downloadable PDFs from 30Minute<strong>Shakespeare</strong>.com.

British actress Daisy<br />

Ridley, who plays the<br />

title role in Ophelia.<br />

26 shakespeare magazine

Time<br />

Travelling<br />

with Ophelia<br />

Painter, illustrator and occasional actor<br />

Stewart Kenneth Moore shares his<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

shakespeare magazine 27

(Left to right) Daisy Ridley as Ophelia,<br />

and as Rey in Star Wars: The Last Jedi.<br />

ot so much<br />

“Who’s There?”<br />

as “Who and where<br />

am I?” While they moved<br />

the time machine I took<br />

in my surroundings. I had<br />

become an old priest, moored,<br />

anchored, for a few days,<br />

somewhere deep in the past. The<br />

location could not have been more<br />

beautiful. Seated at the edge of all the<br />

machines I looked out at a stunning<br />

summer view, a small pond, a steep field of green<br />

grass running away from me to meet a hillside and<br />

escape into a tree line in the sunset.<br />

Actors are time travellers and cameras are time<br />

machines. They capture light and change its speed,<br />

they frame the moment forever. Films take you back<br />

to the past and they wait as time capsules for future<br />

generations.<br />

If you ever find yourself in costume, on a film<br />

set, somewhere deep in the countryside, you will<br />

know how easy it is to imagine you are actually in<br />

some past century. Easy, that is, until you get hungry<br />

and wander back to Catering and leave the hazy<br />

world of fireflies for that of the crackle of walkietalkies<br />

and gaffer tape.<br />

I had been cast in Ophelia, the new film directed<br />

by Claire McCarthy starring Daisy Ridley in the<br />

titular role. Based on the novel by Lisa Klein, this<br />

is the story of Hamlet and Ophelia retold from<br />

the point-of-view of Ophelia. In this way the<br />

story shares similarities to the Tom Stoppard play<br />

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Both take a<br />

parallax view of the classic narrative.<br />

The pond was not in shot but it made me think<br />

of the painting of Ophelia by John Everett Millais.<br />

The time-machine (the camera) was behind me<br />

at a small yard that seemed like an old abandoned<br />

graveyard with one small section of chapel wall<br />

remaining. A scene both humble and epic that could<br />

have been painted by John William Waterhouse.<br />

Czech set builders are so very good at their work<br />

that I’ve given up trying to discern reality from<br />

set design. This little yard sat at the edge of a tiny<br />

village, not even a village – a hamlet. No pun<br />

intended. The residents were out silently watching<br />

the strange goings on. Hollywood had appeared<br />

out of nowhere with its time machine and its many<br />

trucks and time travellers (crew). The locals stood<br />

and watched as we changed the weather, conjuring a<br />

cold downpour on a warm summer evening, I think<br />

28 shakespeare magazine

“Ophelia has an excellent cast, including<br />

Daisy Ridley, Naomi Watts and Clive Owen”<br />

we may even have brought the moon with us. This<br />

is a fairly vast illuminated ball, a moon in essence,<br />

that is lassoed and suspended nearby for lighting<br />

purposes.<br />

It takes a long time to film a few scenes because<br />

we go back and forth filming various close-ups and<br />

reaction shots, and from this the editor will later put<br />

together an aggregate of all our actions and reactions.<br />

It’s always a surprise to see the final outcome. You<br />

might shoot a scene ten different ways, so you’d<br />

think you’d have a good memory of what happened,<br />

yet it’s always a surprise to see the final version.<br />

The theme of Hamlet and Ophelia has been<br />

popping up in my work for years now. I’ve sketched<br />

my fellow actors at work, mostly on stage. The series<br />

that has slowly emerged, such as it is, has no real<br />

title and I’m not planning on showing it any time<br />

soon, but it’s basically a study of ‘stagecraft’. I’ve<br />

drawn scenes from Hamlet and Macbeth (on stage<br />

and rehearsals) and even created a Macbeth graphic<br />

novel based on the work of the Prague <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Company. I’ve also studied the players of Blood,<br />

Love and Rhetoric at work on Rosencrantz and<br />

Guildenstern Are Dead. So my studio has quite a few<br />

images based on some form of Hamlet. Add to this<br />

the redoubling weirdness of a chat between scenes<br />

with an actor who, I suddenly realise, is the son of<br />

that particular parallax playwright.<br />

All of this made working on this film very<br />

familiar and more than a bit coincidental. After all,<br />

I had only just portrayed Czech theologian Jan Hus<br />

(1369-<strong>14</strong>15) for Nat Geo, so I’d been walking the<br />

walk, or, the dogma, only a few weeks prior. And in<br />

the weeks before auditioning I had begun asking why<br />

it was I only ever seem to meet male directors, where<br />

are the female directors? This question seemed like an<br />

epiphany (I am a man, it would). But, I wondered,<br />

where is the female perspective in cinema? And is<br />

the lack of that perspective one reason for the rot?<br />

Probably not, but female direction shouldn’t be a<br />

parallax view, it should be just another norm. To this<br />

day I’ve never met a female director of photography.<br />

I’ve met and worked with a few female student<br />

directors, perhaps an indication of the changing<br />

balance, but never on a big budget film, or any film<br />

for that matter. The only exception being Susan Tully<br />

directing us on an episode of Britannia (the time<br />

machine forcing me back a few thousand years this<br />

time, and into the sandals of a Roman revolutionary)<br />

for Sky television. And then, suddenly, there was<br />

Claire, like Susan, another excellent director and, for<br />

that, no different than so many.<br />

Ophelia (Daisy<br />

Ridley) with<br />

Queen Gertrude<br />

(Naomi Watts).<br />

shakespeare magazine 29

Two of Stewart’s<br />

paintings inspired<br />

by Tom Stoppard’s<br />

Hamlet-referencing<br />

play Rosencrantz<br />

and Guildenstern are<br />

Dead.<br />

By now you may be wondering why I am not<br />

writing about the stars, the roles, other nitty-gritty.<br />

Well, I can’t, time-travellers take a vow of omertà<br />

when they sign on the dotted line. I cannot tell you<br />

what I saw, what happened. I can say that it was<br />

a good-natured place, it was a good set. I might<br />

be able to tell you about a prank I pulled – an<br />

absolute blinder, to be honest – but unfortunately<br />

it is connected with a key moment in the story<br />

and would be a spoiler. I’m no spoiler. I might be<br />

able to tell you about the dead body, a life-cast, an<br />

avatar identical in the smallest detail to an actual<br />

dead man, that lay on the grass and why that was so<br />

hilarious... but I can’t. I can say the villagers noted<br />

it but were apparently unfazed and that too was<br />

amusing.<br />

Ophelia has an excellent cast. As I’ve said, Daisy<br />

Ridley as Ophelia but also starring Naomi Watts<br />

(Gertrude), Clive Owen (Claudius) and Tom<br />

Felton (Laertes). Two you may not know – George<br />

MacKay as Hamlet and Devon Terrell in the role of<br />

Horatio – are both superb actors. I didn’t realise I’d<br />

seen George in one of my favourite TV shows of the<br />

previous year. He was in the miniseries 11.22.63,<br />

about a time traveller, played by James Franco,<br />

attempting to prevent the assassination of John F<br />

Kennedy. I wished I could have told him how much<br />

I enjoyed the series.<br />

Stranger still, when I got home my son suggested<br />

we watch a film after dinner, one he’d been waiting<br />

to see. He’s very interested in politics and told us<br />

about a film about the young Obama, he chose it<br />

out of the blue. I was stunned and found myself<br />

saying “You’re not going to believe this, but I was<br />

just in the car with that guy... today!”<br />

It is interesting to see how actors shape a scene<br />

and, in some sense, are guardians of logic in the<br />

story. The time machine sometimes remains on<br />

standby while an actor questions the logic of an<br />

action. It may all become clear to the actor and we<br />

move forward in time as planned. Or the director<br />

may be alerted by the actor to the lack of logic in<br />

the scene, make some adjustment, and the timeline<br />

shifts slightly and the scene becomes more logical,<br />

it can go either way. This is the alchemy of motion<br />

picture storytelling at its heart, and actors don’t get<br />

much credit for those key moments.<br />

Before you know it, it’s a wrap and the set and all<br />

its players evaporate. Before you know it, the whole<br />

crazy event is over and “Tis in my memory lock’d...”<br />

<br />

Stewart Kenneth Moore (aka Booda) is a painter,<br />

graphic novelist and actor. He has recently completed<br />

acting work on Lore for Amazon, and is currently<br />

developing a new comic strip with writer Pat Mills.<br />

You can buy his graphic novel of Macbeth<br />

Here<br />

30 shakespeare magazine

Want to wear your heart<br />

on your sleeve and the<br />

Bard on your chest?<br />

Get a fabulous exclusive <strong>Shakespeare</strong> T-shirt<br />

when you donate to <strong>Shakespeare</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong>!<br />

Donate here

Samira Ahmed<br />

“The third<br />

age of Hamlet<br />

for women is<br />

post-40. I am<br />

completely<br />

Team<br />

Gertrude”<br />

32 shakespeare magazine

Samira Ahmed <br />

Brodcaster and cultural critic Samira Ahmed<br />

grapples with one of the the thorniest questions<br />

in literary and theatrical history…<br />

“Why do<br />

women love<br />

Hamlet?”<br />

shakespeare magazine 33

Samira Ahmed<br />

Samira<br />

interviewed<br />

Tom Hiddleston<br />

in March 2017.<br />

here are three ages of<br />

Hamlet. Like a lot of women, I first<br />

encountered Hamlet as a teenager, and<br />

of course I fell in love. He’s misunderstood<br />

by the adults, he’s disgusted by their phoneyness.<br />

So far all so very Holden Caulfield.<br />

The first soliloquy “Oh that this too too<br />

sullied flesh...” is when you fall in love with<br />

Hamlet.<br />

However as you get older, by your late twenties,<br />

the way Hamlet treats Ophelia is impossible to<br />

reconcile. It’s like Molly Ringwald rewatching the<br />

old John Hughes movies, shocked at the sexual<br />

harassment all the way through – seeing Judd<br />

Nelson looking up her skirt. All the crude sexual<br />

references. What way is that to speak to the woman<br />

you love? And in the age of Me Too, I think it’s<br />

interesting how we try to find get-out clauses for<br />

Hamlet. There’s something of the tormented dark<br />

soul in romantic fiction that you can trace back to<br />

Hamlet that appeals to young women who think<br />

they can rescue him. Even Kylo Ren in Star Wars.<br />

Misunderstood, cruel because he’s tormented<br />

and, guess what, it’s all tied up with his dodgy<br />

relationship with his father, grandfather and his<br />

hated Uncle Luke. There are revisionist Hamlets<br />

where women have rightly tried to give Ophelia<br />

more agency for female readers. The YA novel<br />

Dating Hamlet by Lisa Fiedler was written with<br />

that in mind. In the intro it says “She felt female<br />

characters like Ophelia always got a raw deal...<br />

so she gave them the guts to change their own<br />

destinies”.<br />

The third age of Hamlet for women is post-<br />

40. I am completely Team Gertrude. I realised<br />

she might well have been only 15 when she had<br />

an arranged marriage, possibly to a much older<br />

man. What was really made clear in the wonderful<br />

34 shakespeare magazine

Samira Ahmed <br />

“By your late<br />

twenties, the way<br />

Hamlet treats<br />

Ophelia is impossible<br />

to reconcile”<br />

Clockwise from top:<br />

Star Wars baddie Kylo Ren has some<br />

of Hamlet’s darkly destructive angst.<br />

Laurence Olivier’s hugely<br />

Hamlet.<br />

Maxine Peake played Hamlet at the<br />

<br />

Juliet Stevenson as Hamlet’s mother<br />

Gertrude, 2017.<br />

shakespeare magazine 35

Samira Ahmed<br />

Andrew Scott/Juliet Stevenson Almeida/West End<br />

production last year was how she was finally in a<br />

happy marriage and having wonderful sex for the<br />

first time with a considerate lover. I did discuss this<br />

with Juliet Stevenson, so I know I’m right. And<br />

here’s Hamlet, totally self-absorbed and unable<br />

to cope with the idea that she has basically finally<br />

found happiness with another man. Actress Nicola<br />

Walker told me Sarah Phelps has written a version<br />

of Hamlet from Gertrude’s point of view. Perhaps<br />

we need more of that, in the way that Jean Rhys’<br />

Wide Sargasso Sea was able to give Bertha’s story<br />

and challenge Jane Eyre.<br />

I don’t have a problem with women playing<br />

Hamlet. We need to take ownership of the right to<br />

be the angst-ridden hero/ine who matters, and it<br />

emphasises the feminine aspects of the character –<br />

but I think it changes everything. Under patriarchy<br />

a female Hamlet is such a different being. I find<br />

it interesting that Janet Suzman – a very famous<br />

Ophelia opposite David Warner – wrote a book,<br />

Not Hamlet, frustrated by the lack of such a part<br />

for women, but is insistently against women<br />

playing those male roles.<br />

The thing I can’t fathom is Hamlet being 30.<br />

That makes no sense, for him as a young romantic<br />

hero. That seems practically middle-aged for<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s age, though more palatable today in<br />

the age of eternal middle youth.<br />

But I would say Hamlet can still grip your<br />

heart the way he did when I was a young girl. The<br />

Paapa Essiedu RSC Hamlet moved me more than<br />

any for years, for the tears in his eyes as he faces his<br />

death at the end, suddenly realising how, despite<br />

all his clever plotting, he was a naive young man,<br />

who could not conceive of the depth of the adult<br />

wickedness of his Uncle and his courtiers. For all<br />

his faults, he is a noble soul.<br />

<br />

<br />

36 shakespeare magazine

You know him as an actor, playwright,<br />

literary genius…<br />

But now it’s time to meet the real<br />

William <strong>Shakespeare</strong><br />

Out Damned Spot! is available now from Amazon and all good bookshops<br />

urbanepublications.com

Victorian Hamlet<br />

“A hundred<br />

ducats apiece<br />

for his picture<br />

in little...”<br />

The Victorian Illustrated <strong>Shakespeare</strong> Archive is a<br />

wondrous free resource compiled and curated by<br />

Dr Michael Goodman of Cardiff University. So we<br />

asked him to select some of his favourite examples<br />

of Hamlet-related artwork from the archive.<br />

1. Kenny Meadows,<br />

Hamlet Dramatis Personae<br />

This is a clever example of the illustrator Kenny<br />

Meadows commenting upon the theatricality of<br />

the page and, indeed, the illustrated edition itself.<br />

By alluding to the device traditionally used in the<br />

theatre to signify the start of a play – the lifting of<br />

the curtain – Meadows draws (quite literally) our<br />

attention to the differences between stage and page<br />

and wittily challenges us to reconcile the two. But<br />

there is something more going on here. Hamlet is<br />

a play which is all about looking – things seen and<br />

unseen, the observer becoming the observed, and<br />

the dangers that lie with misunderstanding what<br />

our eyes are telling us. By opening his illustrated<br />

imagining of the play in this way, Meadows is also<br />

implicating us, the readers, within the play’s narrative.<br />

The illustration is an effective instance of word and<br />

image combining to create a larger and more richer<br />

meaning than they could in and by themselves.<br />

38 shakespeare magazine

Victorian Hamlet <br />

1.<br />

shakespeare magazine 39

Victorian Hamlet<br />

“Knight’s editions focus more on the geography<br />

and objects in the plays than on the characters”<br />

2. 3.<br />

4.<br />

2. G.F. Sargent,<br />

Platform at<br />

Elsinore.<br />

3. G.F. Sargent,<br />

Church and<br />

Churchyard at<br />

Elsinore.<br />

4. G.F. Sargent,<br />

View of Elsinore.<br />

40 shakespeare magazine

Victorian Hamlet <br />

5.<br />

5. G.F. Sargent,<br />

Hamlet’s Grave<br />

One of the most overlooked<br />

editions in VISA (going by the<br />

stats) is the one published by<br />

Charles Knight. Knight, who was<br />

a publisher and not an illustrator,<br />

included in his edition the work<br />

of many different artists in many<br />

different styles, and I suspect the<br />

reason this edition is the least<br />

used is because it focuses more<br />

on the geography and objects of<br />

the plays than on the characters.<br />

In effect, the edition singularly<br />

treats each play like a history<br />

play – as if they depict actual<br />

historical events. Nevertheless, it<br />

is a fascinating document which<br />

reveals what Knight thought<br />

<br />

audience to know about the plays<br />

of William ‘Shakspere’ (Knight was<br />

preoccupied by ideas of historical<br />

authenticity and concluded, along<br />

with others, that ‘Shakspere’ was<br />

the likely spelling of ‘<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’<br />

in the early modern period).<br />

When I have been teaching<br />

students, a valuable way of<br />

approaching the illustrations<br />

in Knight’s edition has been to<br />

think of them, to use a term<br />

from cinema, as setting up an<br />

‘establishing shot’ and depicting<br />

the scene where the play’s<br />

action will take place. These four<br />

examples, all by the artist G.F.<br />

<br />

this. We see Elsinore Castle from<br />

a distance (2) and then we can<br />

‘zoom in’ closer in the illustration<br />

in ‘Platform at Elsinore’. We can<br />

use the same strategy again with<br />

the illustrations ‘Church and<br />

Churchyard at Elsinore’ before<br />

transitioning to ‘Hamlet’s Grave’.<br />

But let’s, for the time being,<br />

imagine that we could zoom in<br />

even further onto the ‘Platform at<br />

Elsinore’. What would we see?<br />

shakespeare magazine 41

Victorian Hamlet<br />

6.<br />

6. H.C. Selous, The Ghost.<br />

We would probably witness<br />

Horatio encountering Hamlet’s<br />

Ghost, as depicted here by Henry<br />

Courtney Selous. This is not just<br />

one of my favourite illustrations<br />

from Hamlet, but one of my<br />

favourites in the whole archive.<br />

Whilst the other illustrators<br />

depict the ghost shrouded in<br />

darkness or unsatisfactorily,<br />

Selous uses his characteristic<br />

light style to create an image that<br />

is bold, distinct and satisfyingly<br />

composed. There is a real sense<br />

of physicality to both Horatio<br />

and Marcellus, which makes the<br />

disparity between them and the<br />

otherworldliness of the ghost<br />

even more pronounced.<br />

Indeed, what this illustration<br />

<br />

wood engraver – the craftsman<br />

who would realise the artist’s<br />

illustrations by engraving them<br />

onto a block of wood. If you look<br />

closely at many Victorian wood<br />

engraved Illustrations you will<br />

often see two signatures. In this<br />

case, at the bottom left of the<br />

image you can just about make<br />

out the initials H.C.S (Henry<br />

Courtney Selous, the illustrator),<br />

whilst on the right we see the<br />

signature of F. Wentworth (the<br />

engraver). The signatures remind<br />

us that the world of Victorian<br />

image making, much like the<br />

theatre, was a collaborative<br />

process and often, in the case<br />

of these illustrated editions, an<br />

elaborate production as well.<br />

7. H.C. Selous, Hamlet Full Page<br />

Introductory Illustration.<br />

42 shakespeare magazine

Victorian Hamlet <br />

7.<br />

shakespeare magazine 43

Victorian Hamlet<br />

8.<br />

8. Kenny Meadows,<br />

Hamlet Introductory Remarks<br />

Just as there are innumerable<br />

ways to stage one of<br />

<strong>Shakespeare</strong>’s plays, there are<br />

also a vast amount of ways to<br />

illustrate them. One of the most<br />

interesting aspects of VISA is<br />

that it allows us to easily explore<br />

how the different illustrators<br />

interpreted the same scene. These<br />

two illustrations by Selous and<br />

Meadows are a case in point with<br />

both demonstrating the different<br />

artistic styles of the two artists. In<br />

<br />

could be very much be mistaken<br />

in thinking that Hamlet is a sort of<br />

pastoral drama – a kind of more<br />

serious counterpart to As You<br />

Like It. With Meadows’ illustration,<br />

<br />

realm of the macabre and the<br />

gothic.<br />

While Selous’ illustration<br />

represents wickedness occurring<br />

in an idyllic landscape (the snake<br />

on the ground makes us think<br />

that we could be in the Garden<br />

of Eden here), in Meadow’s<br />

interpretation of the scene<br />

even the trees look dark and<br />

malevolent. Something is indeed<br />

rotten in the state of Denmark.<br />

As ever with Meadows there is<br />

also some fourth wall breaking<br />

going on as well, with Claudius<br />

(or is it?) clutching at the wall<br />

with ‘Introductory Remarks’<br />

written upon it. The effect is<br />

unsettling for the reader and it<br />

is possibly a visual reference to<br />

Claudius’ line in Act III when he<br />

talks about his ‘cursed hand’. The<br />

fact that both these illustrations<br />

appear near to the start of their<br />

respective editions (before the<br />

play has actually begun) means<br />

<br />

purpose a trailer does for a<br />

<br />

<br />

moments of drama and we wish<br />

to learn more.<br />

44 shakespeare magazine

Victorian Hamlet <br />