You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

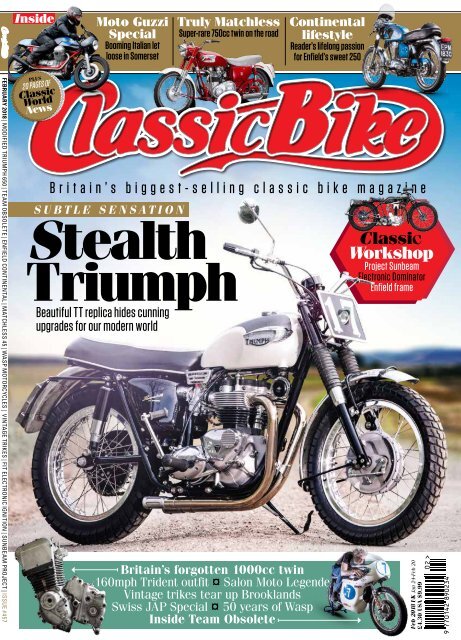

Inside<br />

Moto Guzzi<br />

Special<br />

Booming Italian let<br />

loose in Somerset<br />

Truly Matchless<br />

Super-rare 750cc twin on the road<br />

Continental<br />

lifestyle<br />

Reader’s lifelong passion<br />

for Enfield’s sweet 250<br />

FEBRUARY 2018 | modified triumph 650 | team obsolete | enfield continental | matchless 45 | wasp motorcycles | vintage trikes | fit electronic ignition | sunbeam project | <strong>issue</strong> #457<br />

PLUS<br />

20 pages of<br />

Classic<br />

World<br />

News<br />

B r i t a i n ’ s b i g g e s t - s e l l i n g c l a s s i c b i k e m a g a z i n e<br />

subtle sensation<br />

Stealth<br />

Triumph<br />

Beautiful TT replica hides cunning<br />

upgrades for our modern world<br />

Britain’s forgotten 1000cc twin<br />

160mph Trident outfit ¤ Salon Moto Legende<br />

Vintage trikes tear up Brooklands<br />

Swiss JAP Special ¤ 50 years of Wasp<br />

Inside Team Obsolete<br />

Workshop<br />

Project Sunbeam<br />

Electronic Dominator<br />

Enfield frame<br />

Feb 2018 UK Jan 24-Feb 20<br />

£4.30 USA $9.99

The<br />

<strong>issue</strong><br />

Two fingers on the<br />

clutch? You’d want<br />

more than that on<br />

an earlier Jota...<br />

Sound<br />

The<br />

speed<br />

of<br />

words: Phillip Tooth.<br />

Photography: tim keEton<br />

Velocity is intoxicating, but when it’s combined with a noise that sounds<br />

like a portent of the world’s end, it can only be one thing – a Laverda Jota<br />

70<br />

71

laverda jota<br />

1<br />

2<br />

T<br />

o say that the Jota comes with a<br />

reputation is a massive understatement.<br />

When it was launched in 1976, it was the<br />

fastest road bike that money could buy.<br />

While the Ducati GT I owned at the time<br />

was good for about 115mph and my Le Mans’ top speed<br />

was closer to 130, the legendary Jota was the first overthe-counter<br />

production road bike to top 140mph. It<br />

didn’t matter if it was too heavy and that you had to<br />

bully it round bends, or that you<br />

needed two hands to pull in the<br />

clutch lever, the Jota blew the best<br />

from Japan into the weeds, and<br />

deafened them in the process.<br />

Laverda’s 981cc triple had<br />

launched itself from the Breganze<br />

factory in 1973 with the uninspiring<br />

model name 3C (Tre Cilindri). With<br />

a bore and stroke of 75 x 74mm and<br />

featuring the usual chain-driven<br />

double overhead cams with two<br />

valves per cylinder, designer<br />

Some advertising lines are just hype – but not this one<br />

Luciano Zen went his own way<br />

with a 180° crankshaft. Because the middle piston was<br />

at top dead centre when the outer pistons were at<br />

bottom dead centre, the 3C wasn’t as smooth as a 120°<br />

triple like a Triumph Trident, but it certainly wasn’t<br />

rough – and the power pulses gave the exhausts a brutal<br />

bark. Laverda claimed 80bhp at 7250rpm and a top<br />

speed of 137mph... but you could take those figures with<br />

a large grind of black pepper.<br />

It was British importer Slater Brothers who unleashed<br />

the Beast of Breganze. Richard and Roger Slater had<br />

‘the Jota blew the best from Japan<br />

into the weeds – and deafened<br />

them in the process’<br />

On the gas with the<br />

fastest bike of its<br />

generation<br />

been campaigning a 3C in production racing with some<br />

success. Fork triple clamps from the SFC750 endurance<br />

racer twin were used to give a shorter rake. The engine<br />

delivered extra punch, thanks to a factory cam and<br />

pistons designed for the endurance racers that first<br />

appeared at the Bol d’Or, and the silencers lost their<br />

baffles while the collector pipe was a bit bigger. Those<br />

mods were enough for another 8-9bhp at peak revs, and<br />

that meant harder acceleration. In 1975 Slater Brothers<br />

built a small number of these<br />

racers for the road, and called<br />

them the 3CE (‘E’ for England).<br />

Tested at the Motor Industry<br />

Research Association track, the<br />

latest Laverda recorded a mean<br />

average speed of 133.3mph.<br />

The Breganze factory had also<br />

been busy, upgrading the 3C with<br />

Laverda’s own cast wheels, triple<br />

Brembo discs and a tail fairing to<br />

produce the 3CL for the 1976<br />

season. This was to be the bike<br />

that the Slater Brothers would use<br />

as the basis for the Jota, a name that music-loving Roger<br />

chose after hearing Spanish folk dance songs with a<br />

three/four beat – and they didn’t hang about.<br />

Available from January 1976, the Jota’s engine was<br />

factory-built to Slater’s 3CE specification. The<br />

transmission featured a lower first gear ratio (9.51:1<br />

instead of the 3CL’s 11.24:1) and closer ratios for the<br />

other four, which made the Jota racetrack-ready and a<br />

great bike to ride on fast, open roads. Claimed<br />

maximum power was now 90bhp at 7600rpm. And that<br />

1: High, wide,<br />

handsome –<br />

and very fast<br />

2: Pumper<br />

Dell’Ortos feed<br />

in the fun juice<br />

3: Adjustable<br />

handlebars and<br />

Japanese clocks<br />

are quality touches<br />

4: Just so as you<br />

know what’s<br />

overtaking you<br />

5: Looks like a<br />

silencer – but looks<br />

can be deceptive...<br />

was enough for a two-way average of 137.80mph, with a best<br />

one-way of a benchmark-setting 140.04mph.<br />

Those first Jotas were available in either red or green paint for<br />

the tank and side panels, with a black frame. Silver was the<br />

colourscheme for 1977, with gold an option the following year,<br />

when the Ceriani suspension was replaced by Marzocchi.<br />

Laverda’s official orange race livery and a silver frame graced the<br />

Jota in 1979. For 1980 the cylinder head was redesigned, the<br />

exhaust headers were increased to 36mm diameter and the<br />

clutch got extra plates. There were more changes in 1981, when<br />

the Series II Jota got a bigger-output alternator (up from a barely<br />

adequate 140W supplied by Bosch to an impressive 240W<br />

thanks to Nippon-Denso). The transistorised ignition was<br />

moved to the left side of the crankshaft, and the primary<br />

chaincase grew a bulge as big as mamma’s pasta pot to hide it.<br />

Almost as important, the clutch cable was replaced by a<br />

hydraulic system. The big news for 1982 was a new 120° crank,<br />

but a year later the Jota was replaced by the RGS.<br />

I’d have been happy to throw my leg over any Jota, but the<br />

pick of the bunch has to be the 1981 orange-and-silver version<br />

that owner Terry Sage wheels out of his garage before handing<br />

me the ignition key. Before hitting the starter, I used to openand-close<br />

the twistgrip on my Le Mans so that the pumper carbs<br />

would squirt neat petrol into the combustion chambers. The<br />

Jota also wears pumper Dell’Ortos, but Terry does things<br />

differently. “Just pull back the choke lever a bit and press the<br />

button. It’ll fire immediately, then ease the choke right off.”<br />

The Jota’s soon ticking over reliably. It’s my first surprise.<br />

This Jota is full of surprises. The second is that I can plant<br />

both feet on the ground. The seat height might be a crotchstretching<br />

32in, but the nose of the seat and the rear of the tank<br />

are both slim. I think it was journalist Peter Watson who<br />

described the Jota’s Brevettato ace bars as ‘adjustable to 27<br />

different configurations, none of them comfortable’ – and I still<br />

laugh whenever I see a Jota and think of him. Yet as soon as I set<br />

off, I feel completely at home, easing through rush-hour traffic<br />

and out of the city as if I’d owned this Jota as long as my Duke.<br />

After a quick blast along a dual carriageway, I change down<br />

23<br />

4<br />

5<br />

73

1 laverda jota<br />

into third entering a village and rumble through with<br />

rock-steady needles recording 30mph and 2000rpm on<br />

the Japanese clocks. Read that again: third gear, 30mph,<br />

2000rpm. I didn’t believe it, either – and had to play<br />

with the gearbox to make sure that I was right. Wasn’t<br />

the Jota meant to be a right pain in the neck – and<br />

wrists, and clutch hand – to ride slowly, and only come<br />

into its own when you were thundering across England<br />

at speeds close to twice the legal limit?<br />

But when I crack on, the Jota begins to reveal its true<br />

nature. The engine growls, the exhausts boom and as the<br />

needle swings past 6000 my guts tell me that things are<br />

getting exciting. The Jota can be safely revved to 8500,<br />

but with 500rpm in hand that’s still 60 in first, nearly 90<br />

in second and 110 in third. Two more gears to go...<br />

You don’t ‘think’ a Jota through bends. At 236kg<br />

(522lb) with a gallon of super unleaded, it weighs the<br />

same as my old GT – but most of that weight is carried<br />

much higher. Stay focused. Get your braking done early<br />

and pitch it into the corner. Winding on the throttle<br />

helps to pick the Jota up again and throws it out of the<br />

apex. You’ll have to use muscles you forgot you had, but<br />

it feels good. Who needs a gym when you’ve got a Jota?<br />

On fast sweepers the steering is faultless. You can<br />

relax at 70mph with the engine turning over at a lazy<br />

4000rpm, or cross continents at the ton and still only be<br />

using 5700rpm. Gears snick effortlessly into engagement<br />

and the hydraulic clutch feeds the power in smoothly.<br />

Brake and clutch levers were set up by Ricardo Oro’s<br />

workshop in Breganze, so they are as good as you can<br />

get, but after riding for four hours the thumb muscle on<br />

my left hand was aching and I didn’t like the front brake.<br />

Although it was powerful enough, it had as much feel as<br />

squeezing a pick-axe handle. And the lever was too far<br />

from the handlebar for the span of my dainty paw.<br />

There was time for some cornering photos before we<br />

headed home, and that meant turning around in the<br />

road a half-mile from the bend. We were in the middle of<br />

the country and there was only one house, so I didn’t<br />

think we would disturb anyone, but I was making the<br />

fifth turn when an old woman came out and said<br />

politely: “You are making an awful lot of noise. Can you<br />

please do that somewhere else?” Pointing out that I was<br />

only using half-throttle wasn’t the way to respond, so I<br />

apologised and we moved on. The Jota legend lives.<br />

‘It’s special’<br />

Terry Sage bought and fixed up a<br />

crash-damaged 1976 Laverda 3CL<br />

when he was 19. “I’d been riding<br />

the 3CL for four years, but I really<br />

wanted a Jota. When I saw a<br />

secondhand orange-and-silver one<br />

at Three Cross Motorcycles in 1985<br />

I had to have it.” Terry was working<br />

as a steel erector at the time: “I was<br />

earning good money, but it cost<br />

£3500 so I had to go to the bank<br />

and get ticked up to the eyebrows.”<br />

He was still running his Jota in<br />

1998, but was being left behind by<br />

his mates who were all riding<br />

modern supersports. So he sold the<br />

big triple and bought a Ducati 748.<br />

“I realised I’d made a mistake as<br />

soon as I sold it,” says Terry. He<br />

chopped in the 748 against a 996,<br />

then a 999 and finally 1098S – but<br />

he still hankered after a Jota. “I<br />

know it was loud, heavy and slow<br />

compared to modern sports bikes,<br />

but it was something special.”<br />

He bought another Jota, but had<br />

top-end oil feed problems. Ged<br />

Shorten at GCS found that the six<br />

long studs which fix the cam<br />

bearings, cylinder head and barrel to<br />

the crankcase had been fitted<br />

upside down. As they were<br />

tightened, some of the threads had<br />

been ripped from the crankcase.<br />

The studs are 9mm diameter and fit<br />

in a 10mm hole. Oil is pumped up<br />

the gap to feed the cam bearings<br />

but now the lubricant was simply<br />

returning to the sump.<br />

After the crankshaft was rebuilt<br />

by Keith Nairn of Laverda Scozia,<br />

Ged repaired the crankcase and<br />

rebuilt the engine using Omega<br />

ceramic coated pistons.<br />

With the Jota properly sorted,<br />

Terry is enjoying the good times<br />

again. “My friends all admit that she<br />

can get a move on for an old girl!”<br />

‘The engine growls, the exhausts<br />

boom, the needle swings past<br />

6000... things get exciting’<br />

The legend lives on –<br />

and Phillip survived<br />

the experience, too<br />

74

going native<br />

The Bravest Indians<br />

The recent revival of the Indian marque has brought it back into the<br />

spotlight, so here’s a reminder of its first incarnation. We look at<br />

some of the legendary models that forged the famous firm’s identity<br />

words & Photographs: phillip tooth<br />

▲ 1905 Camelback<br />

On May 24, 1901 Oscar Hedstrom sent a telegram to George Hendee to<br />

tell him that the first Indian was finished. Six days later he was riding the<br />

prototype around Springfield before towing his friend Brooks Page, who<br />

was on a bicycle, up a long hill. Hedstrom’s engine had a capacity of<br />

260cc and was fitted into a bicycle frame, with chain drive and a top<br />

speed of 25mph. The first production Indian was assembled at the<br />

Springfield factory and was on the road in May 1902, with a total of 143<br />

built that year. Three years later a bigger single-cylinder engine rated at<br />

2.25hp was offered, with a bore and stroke of 67 x 82.5mm adding up to<br />

a capacity of 290cc. When this 1905 red Indian (a colour option to the<br />

standard Royal Blue) was first pedalled into life, there was a spring fork<br />

and a twistgrip control to the carburettor. Production rocketed to 1181 in<br />

that year. Speed had increased dramatically and a tuned version covered<br />

the flying mile at 52mph. That was really flying...<br />

▲ 1912 Hedstrom Racer replica<br />

Headline news in 1906 was the addition of the 633cc V-twin racers to the<br />

catalogue, soon followed by the road version (still with a camelback tank).<br />

A single-loop cradle frame replaced the bicycle-style diamond frame in<br />

1909, and there was a coiled spring in a cartridge mounted horizontally<br />

above the mudguard to provide suspension for the forks (although the<br />

famous leaf-spring forks were introduced for the 1910 season. There was<br />

also a new 988cc F-head engine with a mechanical oil pump, and these<br />

engines were reduced to 585cc to make them eligible for the 1911 Isle of<br />

Man Senior TT, the first time the race was run over the Mountain course.<br />

With all-chain drive, a clutch and a two-speed gearbox the red Indians<br />

swept the board with a 1-2-3 finish. At the end of 1911, Indian held all 121<br />

American speed and distance records. For the motodromes, Hedstrom<br />

developed an eight-valve engine but these rare beasts were for the<br />

chosen few. Mere mortals used a tuned F-head like this 1912 racer replica.<br />

1917 PowerPlus<br />

When a road tester arrived back at the Indian experimental department<br />

after a hard, fast ride Charlie Gustafson, who designed the new V-twin,<br />

and Frank Weschler, in charge after founders Hendee and Hedstrom had<br />

retired, stubbed out their cigarettes and walked out to meet him. “What<br />

does she go like?” asked Gustafson. “Man, this motor has power –<br />

plus!” replied the tester. The 998cc side-valve used the same 42° V-twin<br />

angle as the Hedstrom engine. Two years of rigorous testing were<br />

carried out before it would go into production in 1916, but to prove just<br />

how good the Powerplus was, Erwin ‘Cannonball’ Baker fitted a<br />

Powerplus engine to his 1914 Hedstrom chassis to attack the Three Flag<br />

record by setting the shortest time to ride from Canada to Mexico. He<br />

left Vancouver on August 24, 1916, reaching Tijuana on August 27 –<br />

1655 miles of treacherous roads in three days, nine hours, 15 minutes.<br />

“It’s a bear, a big, husky lick-all-comers machine!” Baker enthused. That<br />

rugged useability led to Indian supplying the US Army with nearly 50,000<br />

Powerplus motorcycles after America entered World War I.<br />

▲ 1917 PowerPlus Boardtrack<br />

Somehow, Charles Franklin managed to extract more power out of a<br />

Powerplus engine than Harley’s top tuners could squeeze out of their<br />

eight-valve engines. While the 1917 road bike now featured leaf springing<br />

front and rear, the earliest board track and dirt track bikes used a cut-down<br />

frame and were often raced in rigid form. Later there would be special<br />

Marion frames for the Powerplus racers. The tube that ran under the<br />

engine on the loop cradle frame was cut out, and the engine held in place<br />

with steel plates. It seemed like a backward step when these bikes were<br />

debuted at the 200-mile national championship race in Marion, Indiana in<br />

1919, but the pundits were proved wrong. A Daytona version of the<br />

Marion frame, complete with lowered top tube and headstock, was<br />

adopted in 1920. These frames are easily recognisable because the seat<br />

tube had to be bent into an S-shape in order to make the engine fit<br />

properly. The Daytona soon became the factory riders’ favourite bike, but<br />

there were plenty of farm boys and garage mechanics who raced<br />

stripped-down Powerplus cycles.<br />

ABOVE: Spring forks<br />

went on road bikes;<br />

racers were rigid<br />

both ends<br />

RIGHT: Rugged<br />

but tuneable<br />

Powerplus engine

going native<br />

xxxxxxxxx xxx xx xx<br />

xxxxx xxx xxxxx xx<br />

▲ 1930 Scout 101<br />

‘You can’t wear out an Indian Scout’ was the boast long before the 101<br />

was launched in the spring of 1928. Capacity had been hiked from the<br />

original 600 to 750cc for the 1927 Police Special, and it was this ’45 cubic<br />

inch’ engine that went into the 101. One of the best Indians ever, the new<br />

Scout was about 3in longer, 1in lower at the saddle and even had decent<br />

brakes. Big ‘balloon’ tyres were standard and handling exceptionally good.<br />

For 1931 there was a twistgrip-controlled oil pump to vary the delivery rate<br />

of lubricant. The 75mph 101 Scout was popular for amateur racing and<br />

Wall of Death. Despite the Depression, some 14,000 were sold before it<br />

was (unpopularly) replaced by the 203 Scout – a 750cc using the heavy<br />

Chief chassis – in 1932. The sporting image was regained with the 1934<br />

Sport Scout – a winner for Ed Kretz at the first Daytona 200-miler in 1937.<br />

▲ 1938 Type 438<br />

There was a new four-cylinder engine for the 1936 model year, but it was<br />

a flop. Called the ‘upside-down’ engine because the exhaust valves were<br />

now on the top, it looked ugly and the high exhaust pipe needed a steel<br />

guard to stop it burning the rider’s leg, so for 1938 the Model 438<br />

reverted to the original overhead inlet/side exhaust configuration. The<br />

cylinders were now cast in pairs – testing proved that eliminating some of<br />

the air gaps between cylinders allowed the heat to be pulled into the<br />

airstream more quickly. The aluminium cylinder heads were detachable<br />

with the valve mechanism fully enclosed and automatically lubricated.<br />

There was a streamlined muffler to keep things quieter on this 95mph<br />

motorcycle. Although a left-hand throttle and right-hand gearshift was<br />

standard, a right twistgrip and left gearshift was a factory option.<br />

ABOVE: Indian Big Chief<br />

was a response to the<br />

1200cc Harley<br />

▲ 1925 Big Chief<br />

For the 1920 season a radically different Indian was launched: the 600cc Scout, with semi-unit construction – the engine,<br />

primary drive, clutch and gearbox were locked together. The primary drive consisted of three helical gears, each on roller<br />

bearings, all enclosed in an oil-tight alloy casing. Instead of a single camshaft to operate all four valves there were now two<br />

camshafts, each with a single-lobe cam to operate both inlet and exhaust valves of one cylinder through pivoted cam followers.<br />

Heads and barrels were cast in one piece. The double-loop cradle frame had a flat platform to mount the engine/transmission.<br />

But there were those who demanded more power. Enter the Chief, launched on Labor Day, September 1921. The 998cc<br />

engine delivered about 20hp, enough for brisk acceleration to a top speed of 65mph. But Harley had gone supersize with a<br />

1200cc engine in 1921. The Chief was more technically advanced, but Indian needed something bigger for the 1923 season –<br />

enter the 1200cc Big Chief. In November that year Hendee Manufacturing Company became Indian Motocycle [sic] Company.<br />

▲ 1925 Ace Sport<br />

What’s Ace got to do with Indian? Rather a lot. William Henderson, the<br />

technical brains behind the Henderson Four, had fallen out with Ignaz<br />

Schwinn, whose Excelsior company had taken over Henderson in 1917.<br />

Henderson found new backers and formed the Ace Motor Company in<br />

Philadelphia in 1919, with the first high-performance F-head Aces rolling<br />

out for the 1920 season. But then tragedy struck. In 1922 William was<br />

killed while test riding his latest creation, the very rapid Sporting Solo<br />

model Ace. Ace riders set new cross-country speed records and won<br />

numerous hillclimbs, but financial troubles were never far away. In<br />

December 1927 Indian purchased the Ace assets and marketed the<br />

1300cc Four as the Indian Ace, and up to 1935 all Indian Fours were<br />

essentially Ace, which were essentially Henderson...<br />

▲ 1929 Type 401<br />

While Indian initially produced the Ace virtually unchanged, the 1929<br />

Model 401 adopted more of the parent company’s trademark features.<br />

As well as deleting the Ace name, the tank became a compact teardrop<br />

design. Indian’s famous leaf-spring fork replaced the Henderson-Ace<br />

plunger type and a drum front brake was fitted, complementing the<br />

contracting-band rear. The 401 initially shared the Ace’s single downtube<br />

frame, but vibration <strong>issue</strong>s prompted a twin-tube design based loosely on<br />

the Scout models but using heavier tubing. The new frame was fitted to<br />

the Model 402, available from spring 1929, which also featured a fivebearing<br />

crank to replace the Ace’s three-bearing unit, along with a better<br />

oil pump, redesigned cylinder heads and alloy pistons. The 402 gained<br />

50lb, so riders needed all the available 30hp to stay with the old Ace.<br />

ABOVE: Military Chief<br />

boosted 1940<br />

production<br />

‘These 75mph bikes<br />

were painted in a drab<br />

olive with no hint of chrome’<br />

▲ 1940 Military CHief 340B<br />

Although the US Army selected Harley-Davidson for World War II, in 1940 Indian received an order for 5000 Chief sidecar<br />

outfits from the French army. When events overtook France, most were diverted to other forces, including the Polish Army,<br />

many ending up in Britain - some allegedly ending up at the bottom of the North Sea in torpedoed ships. These 75mph bikes<br />

were painted a drab olive with no hint of chrome, but at least the dispatch riders had the comfort of plunger rear suspension.<br />

41

going native<br />

▲ 1942 Scout 741B<br />

The British, Canadian, Australian and other Allied forces chose the Indian<br />

Model 741B to be used alongside BSA M20 and Norton 16H dispatch<br />

bikes. Designed in 1939, with a capacity of 500cc, the 741B was lighter<br />

and almost as fast as its bigger brother. It revved to almost 5000rpm and<br />

topped out at 65mph. Production ran through to 1944, with about 35,000<br />

made. After the war, many – like this 1942 model – were stripped of their<br />

army uniform and dressed for Civvy Street with a coat of fresh paint.<br />

▲ 1943 Type 841<br />

In 1941 the US Army offered Harley and Indian a $350,000 contract to<br />

build 1000 shaft-driven 750cc twins to rival the WWII BMW. Harley’s XA<br />

was a boxer, but Indian offered a transverse 745cc V-twin., using Sport<br />

Scout cylinders. Put through their paces in summer 1942, Army testers<br />

reckoned the low-centre-of-gravity 841 handled better than the H-D with<br />

a 70mph top speed. A tough call, but there could be only one victor... the<br />

Jeep. They were sold off as war surplus in 1944 for $500 each.<br />

▲ 1946 Chief<br />

If Indian couldn’t compete with Harley’s Knucklehead in the performance<br />

stakes, the 80mph Chief certainly could when it came to style. The big<br />

news for 1940 was the skirted fenders introduced by engineer and stylist<br />

George Briggs Weaver. Although not everyone was impressed with the<br />

look, there were others who thought the skirted fenders made the Chief<br />

the most beautiful bike on the planet and today they are iconic Indian<br />

wear. Also new that year was a plunger-sprung frame, although the forks<br />

retained the leaf spring – that all changed in 1946, however. Indian had a<br />

new owner named Ralph Rogers; times were tough and the Chief was<br />

the only model produced that year, but it came with a new double-spring<br />

girder fork with a hydraulic shock absorber, basically a slimmer version of<br />

the fork developed for the military 841. The Indian head and war bonnet<br />

fender light was introduced for the 1947 model year, but Rogers’ business<br />

was struggling – he was developing a range of lightweight vertical twins<br />

to take on the Brits and finances were tight. The Chief wasn’t listed in<br />

1949, but returned in 1950 with new telescopic forks and a capacity hike<br />

to 1300cc. Three years later production of Indian motorcycles ended and<br />

the Roadmaster Chief was sent to the happy hunting grounds. But today<br />

the Chief and the Scout are back – big time. And you can even buy one<br />

with skirted fenders and that war bonnet light...<br />

▲ 1947 ‘Rainbow’ Chief<br />

In 1933 the Chief went to dry sump lubrication from the old total loss. A<br />

year later it lost the helical-gear primary drive, replaced by a cheaper and<br />

quieter four-row chain – Harley riders joked that the whine from the<br />

geared primary drive sounded like a built-in police siren. The 1935 Chief<br />

looked bang up to date with smooth ducktailed fenders and a striking<br />

Indian chief‘s head decal on the tank. Performance was improved with<br />

cylinder heads designed to increase midrange torque with a small<br />

sacrifice in top speed. But Harley had their own ideas, and in 1936<br />

launched the legendary 1000cc ohv ‘Knucklehead’. Indian’s response?<br />

A tank-top instrument panel and custom paint features – but these did<br />

become a useful selling point, with colour options running to practically<br />

anything the customer wanted. This was a side benefit of Dulux paint<br />

manufacturer E Paul duPont having taken over struggling Indian in 1930.<br />

In 1938 Rollie Free set stock class records at Daytona Beach with<br />

109.65mph for the Chief and 111.55mph for the Sport Scout.<br />

‘harley riders said The primary<br />

drive sounded like a siren’<br />

42

Workshop<br />

Spannering supremo<br />

Rick Parkington welcomes you<br />

to our Classic Workshop<br />

88<br />

Rick’s Fixes Your problems solved 92 Project bike Martinsyde cases 98 Wiring Pt2 Looms for beginners<br />

classicbike.workshop@bauermedia.co.uk

our classics 1?????????????<br />

Workshop<br />

Rick’s<br />

how to<br />

Make vintage bike grips<br />

You can adapt a regular handlebar grip like this...<br />

Fixes<br />

Solving the problems<br />

of the classic world<br />

1Here’s the problem – most handlebar grips have a closed end. If you<br />

have a vintage bike with inverted levers – or a more recent bike with<br />

handlebar weights – you need to make a neat cut.<br />

2<br />

A<br />

knife makes a mess of the job, but a wooden or nylon bar makes<br />

it easy to use a wad punch – the bar gives the necessary support<br />

of an ‘anvil’ against which the punch can do its work.<br />

If the bolt doesn’t fit<br />

the hole, it’s worth<br />

making one that does.<br />

“Clacka-tacka-tacka-tacka-tacka-tacka…”<br />

stammered the Sunbeam’s engine as I peeled off<br />

the main road into a lane. Oops, that doesn’t<br />

sound good. It’s engine speed… piston? Big end?<br />

It’s loud, so more likely piston, but (despite<br />

having opened up a bit to shake off a tailgating<br />

car) there’d been no sign of any seizure.<br />

I limped gently along, home still ten miles<br />

away… Try a hand-pumpful of oil. No<br />

difference, hmmm... I’d expect a splurge of cold<br />

oil to take the edge off a noisy big-end or<br />

piston. Try a bit of ignition retard; taking the<br />

punch out of the combustion usually quietens –<br />

or at least alters – rattles. Not this time...<br />

RICK’S patch<br />

Not as bad as it sounds<br />

A ride on Rick’s latest acquisition results in a noise that sends alarm bells ringing...<br />

‘it would be Just my<br />

luck to blow it up so<br />

soon after buying it’<br />

Who Is Rick?<br />

Rick Parkington<br />

has been riding<br />

and fixing classic<br />

bikes for decades.<br />

He lives and<br />

fettles in a fully<br />

tooled up shed in<br />

his back garden.<br />

My thoughts turned to the events I’ve<br />

booked the bike in for this year – and<br />

what I’d take instead. Just my luck to<br />

blow it up so soon after buying it;<br />

whatever the trouble it can be fixed,<br />

but it will take time and money.<br />

Spotting a lay-by, I pulled in for a<br />

quick look and bingo! The rocker<br />

support plate bolts had come loose, allowing<br />

the rockers to jump about on the head; the<br />

noise was that and the consequent slack in the<br />

tappets. After a few spanner tweaks, we<br />

completed the journey in (relative) silence.<br />

Back home, instead of simply reaching for the<br />

Loctite I had a closer look and the true cause of the<br />

problem became clear. One hole in the side plate is<br />

oversize and a loose fit on the bolt. Without the location<br />

of being a snug fit in the hole, the clamping force of the<br />

bolt will struggle to hold it from shifting and working<br />

loose. I made a shouldered bolt and hopefully that will<br />

be the last I hear of that problem.<br />

ILLUSTRATION: iain@1000words.fi<br />

3Lucky me, I have an arbor press which makes it simple, but a<br />

hammer would also do the job. It may be necessary to turn the<br />

punch after the first blow to ensure a clean cut all the away round.<br />

THE BIG FIX<br />

Do the maths<br />

Bob Covey emailed with what he called a<br />

‘simple’ question. “Rick, my BSA B44 is<br />

stripped for rebuild. It should have a<br />

compression plate, but I can’t find out<br />

what thickness it should be for the correct<br />

9.4:1 ratio. Do you know, or can you tell<br />

me how to work it out?”<br />

I don’t know – and I failed maths<br />

O-level twice before giving up. But thanks<br />

to mechanical problems like this, I’ve<br />

picked up a bit since.<br />

To work out the compression ratio, you<br />

need to know the volume of the<br />

combustion chamber at TDC, measured<br />

by tilting the engine and filling the plug<br />

hole to the bottom threads with a<br />

Higher-tuned Victor had a scary 11.4:1 compression ratio<br />

measured quantity of oil. This, added to<br />

the swept volume of the cylinder and<br />

divided by the combustion volume, will<br />

give you the ratio. For example, if the<br />

combustion volume is 100cc on a 500cc<br />

engine, 100 + 500 = 600. Divide that by<br />

100 and you get 6, or 6:1.<br />

4There we go – a nice, neat job that doesn’t look like it has been<br />

chewed out by mice. One other tip: hairspray makes a good<br />

lubricant for handlebar grips and sticks ’em in place when it dries.<br />

So can you adjust the equation to work<br />

out the combustion volume from the CR<br />

and the capacity? Suppose the 441cc BSA<br />

chamber was 50cc, then 491/50 gives a<br />

ratio of 9.82:1 – close. Trying again, I find<br />

52.5cc chamber volume would give a<br />

441cc engine a 9.4:1 ratio. The next thing<br />

is to work out by how much volume is<br />

increased by, say, a 1mm shim. The B44 is<br />

79mm bore, so using Pi x R sq x H, we<br />

can work out that a 79mm x 1mm<br />

cylinder has a volume of 0.49cc (which is<br />

hardly surprising since a 490cc Norton’s<br />

bore and stroke is 79 x 100).<br />

So, for instance, if Bob’s current volume<br />

is 51.52 (working out at 11.7:1) he would<br />

need a 2mm shim to correct it.<br />

I reckon my maths teacher should eat<br />

his cruel words…<br />

86<br />

87

ick’s fixes<br />

Workshop<br />

RICK answers your queries<br />

Studying studs Pt1<br />

Tony Dodsworth in Johannesburg is<br />

building a pre-unit 500cc Triumph<br />

for which he acquired a nice set of<br />

late Speed Twin crankcases, but<br />

there’s a catch: “None of my 500cc<br />

barrels fit them – but 650 barrels do!<br />

Any ideas what’s going on?”<br />

As it happens, Tony, yes. Because<br />

I ran into a similar problem building<br />

my Tribsa scrambler. The answer is<br />

to be found in Harry Woolridge’s<br />

excellent Triumph Speed Twin and<br />

Thunderbird Bible. Prior to 1956,<br />

the barrel stud spacing was different<br />

between 500 and 650 but from then<br />

it was standardised to the 650 pitch<br />

so pre-’56 500 barrels won’t fit.<br />

In my case I had mismatched<br />

cases – one pre-’56, one post – but in<br />

the 30-odd years since I bought<br />

them I only realised when I fitted<br />

cylinder base studs in the empty<br />

holes, having already rebuilt the<br />

bottom end. Luckily I had another<br />

bottom end with the right stud<br />

spacing – but that led to another<br />

problem. Although it appeared to be<br />

the ‘big-bearing’ crankcase I needed,<br />

it turned out to be the big-bearing<br />

casting – but machined for a smallbearing<br />

crank. I managed to<br />

machine it out OK, but it underlined<br />

the fact that although these engines<br />

all look the same, there are<br />

significant changes that need to be<br />

borne in mind.<br />

ABOVE: Barrels<br />

corroded to a<br />

head may require<br />

recourse to a press<br />

LEFT: Late 500cc<br />

Triumph<br />

crankcases share<br />

stud spacings with<br />

the 650, but early<br />

ones do not<br />

Studying studs pt2<br />

Tony Allanson has a particularly<br />

nasty problem to resolve. Corrosion<br />

has stuck his BSA A65 cylinder head<br />

fast onto its studs. After<br />

unsuccessfully trying a spanner on<br />

the crank nut with the combustion<br />

chamber filled with rope (via the<br />

plug hole), he has now removed the<br />

top end as a unit but is unsure where<br />

to go next, heat and penetrating oil<br />

having already failed.<br />

I think the only way to do this is<br />

with a press. The barrel will need to<br />

be supported on flat bars, upside<br />

down. Then I would use two pistondiameter<br />

pieces of aluminium (or<br />

wood) that can be bridged at the<br />

exposed end with a strong plate and<br />

see if the head can be pushed off<br />

that way.<br />

Hopefully, the even pressure<br />

would cause the head to throw in<br />

the towel – but if it’s stubborn,<br />

beware breaking off the cylinder<br />

flange. It may be necessary to have a<br />

thick plate laser cut and drilled to<br />

replicate the crankcase mouth so<br />

that the barrel can be bolted<br />

through all its holes for strength.<br />

Rick’s top tips<br />

Call that sturdy? Lever it out, mate!<br />

I’m not impressed with this new inverted lever, bought by a friend on the<br />

internet. Compared to an original it’s very spindly – little thicker than a<br />

teaspoon handle. You wouldn’t need to be Uri Geller to bend it – as you<br />

might discover under emergency braking...<br />

This is not what I call boxing clever<br />

My mate Bruce showed me a customer’s Monet Goyon gearbox that<br />

jumps out of gear. Despite being a matched pair, the machining was way<br />

out, with the selector shaft misaligned by 5mm! It’s all fixed now, but be<br />

aware – just because it’s original doesn’t necessarily mean it’s correct...<br />

88

ick’s fixes<br />

Taking a peak<br />

Pete Grogan emails from Australia,<br />

asking about the headlight peak<br />

he’s spotted on one of my bikes.<br />

“Was there any benefit in these or<br />

were they just cosmetic? I like the<br />

look and am trying to find one for<br />

my BSA Super Rocket,” he says.<br />

These peaks were an anti-dazzle<br />

accessory, first seen on acetylene<br />

lamps in the vintage era and<br />

re-introduced in the 1950s – despite<br />

the improbability of dazzling<br />

anyone with a 6v 30/24watt<br />

headlight bulb!<br />

Adding a bit of ‘bling’ to the<br />

front end, they regained popularity<br />

during the Rocker era. Very hard to<br />

find by the time I started looking, I<br />

managed to get the odd one here<br />

and there until I had one on every<br />

bike I owned – including a little one<br />

Workshop<br />

on my 98cc Excelsior. My dad<br />

regarded them as bolt-on junk that,<br />

if anything, slowed the bike down<br />

and I eventually gave in and<br />

stopped using them. But finding I<br />

had a couple left recently, I fitted<br />

them for old time’s sake.<br />

These days they are popular<br />

accessories for British classic cars of<br />

the ’50s and ’60s, which also used a<br />

7in headlight, so they fit just the<br />

same. They have a turned-up lip<br />

that clips in between the lamp glass<br />

and the rim, retained by the<br />

headlight W-clips – although the<br />

peak sometimes slips round to a<br />

jaunty angle, so I usually glue them<br />

in place with some silicone sealant.<br />

You can probably find them at<br />

car shows or online, but avoid ones<br />

for VW Beetles – the laid-back<br />

headlight position means the peak<br />

points down when fitted to a bike.<br />

Love them or hate<br />

them, headlight<br />

peaks have been<br />

around a long time<br />

RICK’s final word<br />

Signed and sealed<br />

Bill Hannah writes to suggest I retract my advice<br />

about machining pre-unit Triumph timing covers to<br />

accept an oil feed seal instead of the standard<br />

phosphor bronze bush (Fixes February). He says<br />

although this conversion is alleged to improve oil<br />

pressure, he has seen the seal lip ‘blow out’, resulting<br />

in zero pressure and a wrecked engine. The original<br />

bush, he points out, can wear but cannot fail<br />

completely, adding that if the cover has been cast<br />

off-centre, the hole will ‘daylight’ if machined,<br />

needing an ally-welded repair (see above).<br />

Well, I understand your concern, Bill, but this is<br />

not my experience. I had my first cover converted in<br />

the mid-’80s after finding that new bushes were no<br />

longer available. My casting was off-centre, causing<br />

the circlip groove to break though at one point but it<br />

worked perfectly for years on my Tribsa before<br />

getting ‘borrowed’ for a ’59 Thunderbird. It’s still on<br />

there and I have never even changed the seal since.<br />

In my feature on ‘Rockerbox’ a while ago, I<br />

passed on their warning about cheap pattern seals –<br />

apparently there have been some very flimsy ones on<br />

the market, and suspect these caused Bill’s problem.<br />

Triumph fitted garter seals to all big twins from ’63-<br />

on and I don’t remember hearing of any problems –<br />

even with the 750’s uprated oil pump. The seal<br />

conversion may not be an improvement but it’s an<br />

easy fix and I still can’t see anything wrong with it.<br />

RIDE WITH<br />

CONFIDENCE<br />

UPGRADE TO VENHILL - TESTED AND TRUSTED<br />

CABLES/HOSES /CONTROLS<br />

VINTAGE/MODERN/ROAD/MX<br />

HOSES TUV AND<br />

DOT APPROVED<br />

HEAT RESISTANT<br />

PTFE LINER<br />

FACTORY TESTED<br />

TO 1500PSI<br />

UK MADE FOR<br />

50 YEARS<br />

MARINE GRADE<br />

STAINLESS STEEL<br />

CUSTOM BUILT<br />

SERVICE<br />

01306 885111<br />

VENHILL.CO.UK<br />

FOR MORE INFORMATION AND FULL PRODUCT RANGE VISIT OUR WEBSITE

ON<br />

SALE<br />

APRIL 4<br />

ONLY<br />

£5.99<br />

Find us in WHSmith, selected newsagents or order online at<br />

www.greatmagazines.co.uk/motorcycling and get free UK p&p