Torah in the Mouth.pdf

Torah in the Mouth.pdf Torah in the Mouth.pdf

Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Oral Tradition in Palestinian Judaism, 200 BCE - 400 CE Jaffee, Martin S., Samuel and Althea Stroum Professor of Jewish Studies, University of Washington Print publication date: 2001, Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2003 Print ISBN-13: 978-0-19-514067-5, doi:10.1093/0195140672.001.0001 particular about the Temple/provinces distinction that concerns the rest of the list, while the latter assume the distinction but break the formulaic unity of 2–7. These must be regarded, therefore, as expansions of the primary list. It is difficult to say whether the purpose is to reach 10 items or simply to include other material deemed relevant. All of these expansions employ formulary patterns equally suited to oral or written transmission. But during the time that items 2–7 may have circulated as an independent unit of learned tradition, it is most unlikely that any expansions would have end p.108 departed from so elegant a pattern of formulation. Rather, additions should have been homogenized into the existing rhythmic pattern. The expansions in their present form, therefore, suggest the activity of an editor/compiler working with discrete sources who maintains their anterior stylistic integrity. It is possible that these sources are mediated orally and are shaped by slightly different patterns of formulation. But the editorial work of combining them seems more amenable to a scribal copyist/editor, untroubled by mnemonically managing an abundance of formulaic styles, than to a memorizer who seeks to assimilate new orally encountered material to the ingrained pattern established by older material firmly rooted in a prior oral-performative tradition. The nature of the final contributions to the list certainly confirms this judgment. Comparable to what we have already observed in Tamid, we have a series of comments which assume the presence before the commentator of a completed text. He now supplies some useful but ultimately extrinsic bits of information in the names of acknowledged masters of tradition. The result is certainly still memorizable—but the composition of the whole implies the necessary use of written notation regardless of how the text may ultimately have reached its audience in peformance. 33 The Complex Mnemonic of Mishnah Pesahim 2:5–6 Another probe into Mishnaic compositional phenomena will confirm the essential ambiguity of the evidence for an exclusively oral substrate to Mishnaic tradition. One important characteristic of oral tradition, highlighted especially by literary and anthropological research, is its complex mnemonic technology. Metrical conventions, syntactical rules, verbal homologies, and other techniques are all crucial to the composition and transmission of oral material. 34 This aspect of oral tradition surfaces in the Mishnah in a variety of settings. Here we consider the example of yet another list—indeed, a catalogue of four lists—which enumerates foods that satisfy certain requirements of the ritual meal consumed on the first evening of Passover. The biblical text enjoins Israelites to sacrifice a lamb on the eve of Passover and to consume it roasted, with unleavened bread and bitter herbs (Ex. 12:8). The following is an account of the grain that might be used in the bread and the vegetables that might be served as the herb: 35 end p.109 1. With these one fulfills his obligation on Pesah: —with wheat; —with barley; —with spelt; —and with rye; —and with oats. 2. And they fulfill: —with doubtfully tithed produce; —and with first tithe from which the heave-offering of the tithe is removed; —and with second tithe or temple-dedications which are redeemed. —and priests with dough-offering and with heave-offering. But not: —with untithed produce; —and not with first tithe from which the heave-offering of the tithe has not been removed; —and not with second tithe or temple-dedications which are not redeemed. Thank-offering loaves and the wafers of ascetics—if he made them for himself, he does not fulfill with them; if he made them to sell at market, he fulfills with them. 3. And with these greens one fulfills his obligation on Pesah: —with lettuce; —and with chicory; PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2003 - 2011. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/oso/public/privacy_policy.html). Subscriber: Columbia University; date: 20 September 2011

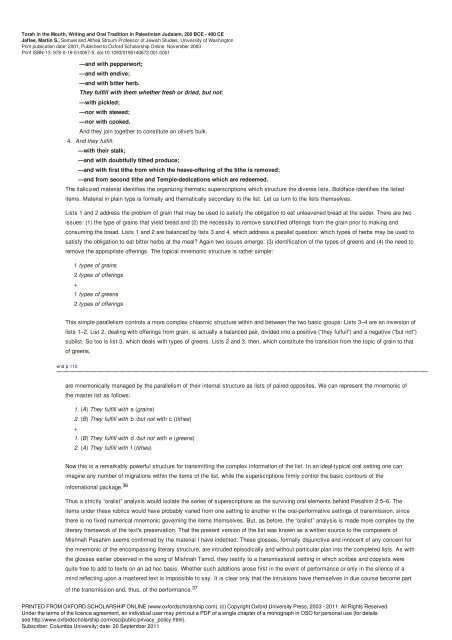

Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Oral Tradition in Palestinian Judaism, 200 BCE - 400 CE Jaffee, Martin S., Samuel and Althea Stroum Professor of Jewish Studies, University of Washington Print publication date: 2001, Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2003 Print ISBN-13: 978-0-19-514067-5, doi:10.1093/0195140672.001.0001 The italicized material identifies the organizing thematic superscriptions which structure the diverse lists. Boldface identifies the listed items. Material in plain type is formally and thematically secondary to the list. Let us turn to the lists themselves. Lists 1 and 2 address the problem of grain that may be used to satisfy the obligation to eat unleavened bread at the seder. There are two issues: (1) the type of grains that yield bread and (2) the necessity to remove sanctified offerings from the grain prior to making and consuming the bread. Lists 1 and 2 are balanced by lists 3 and 4, which address a parallel question: which types of herbs may be used to satisfy the obligation to eat bitter herbs at the meal? Again two issues emerge: (3) identification of the types of greens and (4) the need to remove the appropriate offerings. The topical mnemonic structure is rather simple: 1 types of grains 2 types of offerings + 1 types of greens 2 types of offerings This simple parallelism controls a more complex chiasmic structure within and between the two basic groups: Lists 3–4 are an inversion of lists 1–2. List 2, dealing with offerings from grain, is actually a balanced pair, divided into a positive (“they fulfull”) and a negative (“but not”) sublist. So too is list 3, which deals with types of greens. Lists 2 and 3, then, which constitute the transition from the topic of grain to that of greens, end p.110 are mnemonically managed by the parallelism of their internal structure as lists of paired opposites. We can represent the mnemonic of the master list as follows: 1. (A) They fulfill with a (grains) 2. (B) They fulfill with b /but not with c (tithes) + —and with pepperwort; —and with endive; —and with bitter herb. They fulfill with them whether fresh or dried, but not: —with pickled; —nor with stewed; —nor with cooked. And they join together to constitute an olive's bulk. 4. And they fulfill: —with their stalk; —and with doubtfully tithed produce; —and with first tithe from which the heave-offering of the tithe is removed; —and from second tithe and Temple-dedications which are redeemed. 1. (B) They fulfill with d /but not with e (greens) 2. (A) They fulfill with f (tithes) Now this is a remarkably powerful structure for transmitting the complex information of the list. In an ideal-typical oral setting one can imagine any number of migrations within the items of the list, while the superscriptions firmly control the basic contours of the informational package. 36 Thus a strictly “oralist” analysis would isolate the series of superscriptions as the surviving oral elements behind Pesahim 2:5–6. The items under these rubrics would have probably varied from one setting to another in the oral-performative settings of transmission, since there is no fixed numerical mnemonic governing the items themselves. But, as before, the “oralist” analysis is made more complex by the literary framework of the text's preservation. That the present version of the list was known as a written source to the composers of Mishnah Pesahim seems confirmed by the material I have indented. These glosses, formally disjunctive and innocent of any concern for the mnemonic of the encompassing literary structure, are intruded episodically and without particular plan into the completed lists. As with the glosses earlier observed in the song of Mishnah Tamid, they testify to a transmissional setting in which scribes and copyists were quite free to add to texts on an ad hoc basis. Whether such additions arose first in the event of performance or only in the silence of a mind reflecting upon a mastered text is impossible to say. It is clear only that the intrusions have themselves in due course become part of the transmission and, thus, of the performance. 37 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2003 - 2011. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/oso/public/privacy_policy.html). Subscriber: Columbia University; date: 20 September 2011

- Page 17 and 18: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 19 and 20: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 21 and 22: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 23 and 24: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 25 and 26: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 27 and 28: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 29 and 30: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 31 and 32: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 33 and 34: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 35 and 36: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 37 and 38: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 39 and 40: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 41 and 42: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 43 and 44: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 45 and 46: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 47 and 48: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 49 and 50: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 51 and 52: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 53 and 54: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 55 and 56: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 57 and 58: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 59 and 60: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 61 and 62: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 63 and 64: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 65 and 66: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 67: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 71 and 72: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 73 and 74: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 75 and 76: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 77 and 78: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 79 and 80: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 81 and 82: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 83 and 84: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 85 and 86: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 87 and 88: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 89 and 90: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 91 and 92: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 93 and 94: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 95 and 96: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 97 and 98: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 99 and 100: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 101 and 102: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 103 and 104: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 105 and 106: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 107 and 108: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 109 and 110: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 111 and 112: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 113 and 114: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 115 and 116: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

- Page 117 and 118: Torah in the Mouth, Writing and Ora

<strong>Torah</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Mouth</strong>, Writ<strong>in</strong>g and Oral Tradition <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Judaism, 200 BCE - 400 CE<br />

Jaffee, Mart<strong>in</strong> S., Samuel and Al<strong>the</strong>a Stroum Professor of Jewish Studies, University of Wash<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>t publication date: 2001, Published to Oxford Scholarship Onl<strong>in</strong>e: November 2003<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>t ISBN-13: 978-0-19-514067-5, doi:10.1093/0195140672.001.0001<br />

The italicized material identifies <strong>the</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>matic superscriptions which structure <strong>the</strong> diverse lists. Boldface identifies <strong>the</strong> listed<br />

items. Material <strong>in</strong> pla<strong>in</strong> type is formally and <strong>the</strong>matically secondary to <strong>the</strong> list. Let us turn to <strong>the</strong> lists <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

Lists 1 and 2 address <strong>the</strong> problem of gra<strong>in</strong> that may be used to satisfy <strong>the</strong> obligation to eat unleavened bread at <strong>the</strong> seder. There are two<br />

issues: (1) <strong>the</strong> type of gra<strong>in</strong>s that yield bread and (2) <strong>the</strong> necessity to remove sanctified offer<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>the</strong> gra<strong>in</strong> prior to mak<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

consum<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> bread. Lists 1 and 2 are balanced by lists 3 and 4, which address a parallel question: which types of herbs may be used to<br />

satisfy <strong>the</strong> obligation to eat bitter herbs at <strong>the</strong> meal? Aga<strong>in</strong> two issues emerge: (3) identification of <strong>the</strong> types of greens and (4) <strong>the</strong> need to<br />

remove <strong>the</strong> appropriate offer<strong>in</strong>gs. The topical mnemonic structure is ra<strong>the</strong>r simple:<br />

1 types of gra<strong>in</strong>s<br />

2 types of offer<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

+<br />

1 types of greens<br />

2 types of offer<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

This simple parallelism controls a more complex chiasmic structure with<strong>in</strong> and between <strong>the</strong> two basic groups: Lists 3–4 are an <strong>in</strong>version of<br />

lists 1–2. List 2, deal<strong>in</strong>g with offer<strong>in</strong>gs from gra<strong>in</strong>, is actually a balanced pair, divided <strong>in</strong>to a positive (“<strong>the</strong>y fulfull”) and a negative (“but not”)<br />

sublist. So too is list 3, which deals with types of greens. Lists 2 and 3, <strong>the</strong>n, which constitute <strong>the</strong> transition from <strong>the</strong> topic of gra<strong>in</strong> to that<br />

of greens,<br />

end p.110<br />

are mnemonically managed by <strong>the</strong> parallelism of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>ternal structure as lists of paired opposites. We can represent <strong>the</strong> mnemonic of<br />

<strong>the</strong> master list as follows:<br />

1. (A) They fulfill with a (gra<strong>in</strong>s)<br />

2. (B) They fulfill with b /but not with c (ti<strong>the</strong>s)<br />

+<br />

—and with pepperwort;<br />

—and with endive;<br />

—and with bitter herb.<br />

They fulfill with <strong>the</strong>m whe<strong>the</strong>r fresh or dried, but not:<br />

—with pickled;<br />

—nor with stewed;<br />

—nor with cooked.<br />

And <strong>the</strong>y jo<strong>in</strong> toge<strong>the</strong>r to constitute an olive's bulk.<br />

4. And <strong>the</strong>y fulfill:<br />

—with <strong>the</strong>ir stalk;<br />

—and with doubtfully ti<strong>the</strong>d produce;<br />

—and with first ti<strong>the</strong> from which <strong>the</strong> heave-offer<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> ti<strong>the</strong> is removed;<br />

—and from second ti<strong>the</strong> and Temple-dedications which are redeemed.<br />

1. (B) They fulfill with d /but not with e (greens)<br />

2. (A) They fulfill with f (ti<strong>the</strong>s)<br />

Now this is a remarkably powerful structure for transmitt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> complex <strong>in</strong>formation of <strong>the</strong> list. In an ideal-typical oral sett<strong>in</strong>g one can<br />

imag<strong>in</strong>e any number of migrations with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> items of <strong>the</strong> list, while <strong>the</strong> superscriptions firmly control <strong>the</strong> basic contours of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>formational package. 36<br />

Thus a strictly “oralist” analysis would isolate <strong>the</strong> series of superscriptions as <strong>the</strong> surviv<strong>in</strong>g oral elements beh<strong>in</strong>d Pesahim 2:5–6. The<br />

items under <strong>the</strong>se rubrics would have probably varied from one sett<strong>in</strong>g to ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oral-performative sett<strong>in</strong>gs of transmission, s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is no fixed numerical mnemonic govern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> items <strong>the</strong>mselves. But, as before, <strong>the</strong> “oralist” analysis is made more complex by <strong>the</strong><br />

literary framework of <strong>the</strong> text's preservation. That <strong>the</strong> present version of <strong>the</strong> list was known as a written source to <strong>the</strong> composers of<br />

Mishnah Pesahim seems confirmed by <strong>the</strong> material I have <strong>in</strong>dented. These glosses, formally disjunctive and <strong>in</strong>nocent of any concern for<br />

<strong>the</strong> mnemonic of <strong>the</strong> encompass<strong>in</strong>g literary structure, are <strong>in</strong>truded episodically and without particular plan <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> completed lists. As with<br />

<strong>the</strong> glosses earlier observed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> song of Mishnah Tamid, <strong>the</strong>y testify to a transmissional sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> which scribes and copyists were<br />

quite free to add to texts on an ad hoc basis. Whe<strong>the</strong>r such additions arose first <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> event of performance or only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> silence of a<br />

m<strong>in</strong>d reflect<strong>in</strong>g upon a mastered text is impossible to say. It is clear only that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>trusions have <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>in</strong> due course become part<br />

of <strong>the</strong> transmission and, thus, of <strong>the</strong> performance. 37<br />

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2003 - 2011. All Rights Reserved.<br />

Under <strong>the</strong> terms of <strong>the</strong> licence agreement, an <strong>in</strong>dividual user may pr<strong>in</strong>t out a PDF of a s<strong>in</strong>gle chapter of a monograph <strong>in</strong> OSO for personal use (for details<br />

see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/oso/public/privacy_policy.html).<br />

Subscriber: Columbia University; date: 20 September 2011