Spring 2018 NCC Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

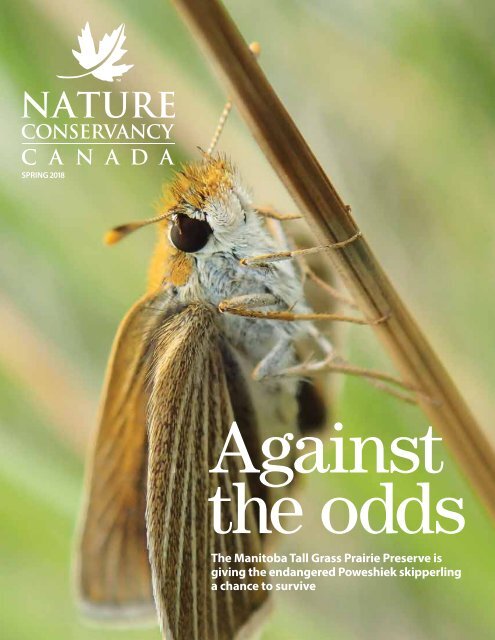

SPRING <strong>2018</strong><br />

Against<br />

the odds<br />

The Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve is<br />

giving the endangered Poweshiek skipperling<br />

a chance to survive

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong><br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410<br />

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 3J1<br />

magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

Phone: 416.932.3202<br />

Toll-free: 800.465.0029<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>)<br />

is the nation’s leading land conservation<br />

organization, working to protect our most<br />

important natural areas and the species<br />

they sustain. Since 1962, <strong>NCC</strong> and its partners<br />

have helped to protect 2.8 million acres (more<br />

than 1.1 million hectares), coast to coast.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong> is<br />

distributed to donors and supporters of <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

TM<br />

Trademarks owned by the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada.<br />

FSC is not responsible for any calculations<br />

on saving resources by choosing this paper.<br />

Printed on Rolland Opaque paper, which<br />

contains 30% post-consumer fibre, is<br />

EcoLogo, Processed Chlorine Free certified<br />

and manufactured in Canada by Rolland<br />

using biogas energy. Printed in Canada with<br />

vegetable-based inks by Warrens Waterless<br />

Printing. This publication saved 29 trees and<br />

104,292 litres of water*.<br />

Design by Evermaven.<br />

COVER<br />

Poweshiek skipperling<br />

Photo by Rachel Caro.<br />

THIS PAGE<br />

Western prairie white-fringed orchid,<br />

Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, MB<br />

Photo by Thomas Fricke.<br />

GENERATED BY: CALCULATEUR.ROLLANDINC.COM<br />

*<br />

2 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Contents<br />

Nature Conservancy of Canada SPRING <strong>2018</strong><br />

Helping hands<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

THOMAS FRICKE. BRENT CALVER. ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

There’s always something new to learn<br />

about the natural world when you work<br />

for a conservation organization. While<br />

producing the spring <strong>2018</strong> issue of the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada <strong>Magazine</strong>, for instance,<br />

I learned that 800 migratory bird species benefit<br />

from laws set in place more than 100 years ago<br />

by Canada and the U.S.<br />

Each spring, as many of these species return<br />

to Canadian soil to breed and nest, Conservation<br />

Volunteers for the Nature Conservancy of Canada<br />

(<strong>NCC</strong>) travel to <strong>NCC</strong> properties from coast to<br />

coast. Volunteers of all ages lend a hand to help<br />

ensure these properties are safe and in good<br />

condition for the birds’ arrival. You can be a part<br />

of those efforts by signing up for an event at<br />

conservationvolunteers.ca.<br />

In this issue, you’ll also read about our efforts<br />

to protect habitat for globally rare species at<br />

risk, such as the Poweshiek skipperling butterfly.<br />

Once a common species, there are now fewer<br />

Poweshieks than pandas; scientists are in a race<br />

against the clock to understand why it is declining.<br />

In our Force for Nature story, we introduce<br />

you to ranchers Scott and Julia Palmer, who<br />

talked to us about their connection to the land<br />

and the impact of their conservation agreement<br />

with <strong>NCC</strong>. And find out how citizen scientists<br />

in Quebec can now be a part of helping turtle<br />

species, such as the snapping turtle.<br />

As the snow melts in coming weeks and signs<br />

of spring begin to emerge, we encourage you to<br />

share your first signs of spring with us. You’ll find<br />

more information on our #<strong>NCC</strong>EarlyBirds photo<br />

contest on page 5 of this issue.<br />

Thank you as always for your support of<br />

our work.<br />

Yours in conservation,<br />

CBT<br />

Christine Beevis Trickett<br />

Director, Editorial Services<br />

8<br />

12<br />

14 For the birds<br />

Honour the Convention for the<br />

Protection of Migratory Birds by<br />

helping to protect Canada’s habitats.<br />

16 Big heart country<br />

The Creemore Nature Preserve brings<br />

together locals in a shared passion<br />

for the natural gem in their backyard.<br />

17 Magic fabric<br />

Outdoor educator Jackie Pye never<br />

forgets to take her Indonesian<br />

sarongs into the great outdoors.<br />

18 Hidden in plain sight<br />

Giving the Poweshiek skipperling<br />

a chance to survive in Manitoba at<br />

the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve.<br />

14<br />

12 Snapping turtle<br />

Built like armoured tanks, with their<br />

mighty jaws and muscular build, these<br />

are Canada’s largest freshwater turtles.<br />

14 Project updates<br />

Protecting the island home of a nationally<br />

rare shrub, ensuring a family’s natural<br />

legacy and honouring one man's efforts.<br />

16 Home on the range<br />

When it comes to tending to the cattle<br />

and land on Palmer Ranch in southwestern<br />

Alberta, it’s all in the family.<br />

18 A chance to thrive<br />

Senator Diane Griffin recalls a memorable<br />

encounter with a Thomson’s gazelle while<br />

on safari in Africa.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 3

COAST TO<br />

COAST<br />

For the birds<br />

Celebrate the protection of more than 800 species<br />

of migratory birds by volunteering to help protect<br />

Canada’s habitats<br />

Over the last century, a number of legal agreements signed by Canada<br />

and the U.S. have helped protect more than 800 species of migratory<br />

birds. In 1916, both countries signed the Convention for the Protection<br />

of Migratory Birds, which aims to stop the indiscriminate and commercial<br />

hunting of migratory birds and protect their nesting sites.<br />

Last year marked the 100-year anniversary of Canada’s Migratory<br />

Birds Convention Act, and <strong>2018</strong> is the centennial of the U.S. Migratory<br />

Bird Treaty Act. All three are among important migratory bird conservation<br />

efforts in North America over the last century.<br />

You can help lend a hand to manage and restore habitat for migratory<br />

birds by becoming a Conservation Volunteer.<br />

Show your love!<br />

Join a community of Canadians<br />

working to protect species and<br />

natural habitats. Like they say,<br />

birds of a feather flock together!<br />

conservationvolunteers.ca<br />

ISTOCK.<br />

TKTK<br />

4 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

SONGBIRDS<br />

Restore and care<br />

for bird habitat<br />

ILLUSTRATIONS: LAURA FETTERLEY. PHOTO: <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

RAPTORS<br />

Become a<br />

citizen scientist<br />

Raptors, or birds of prey, are<br />

species that hunt and feed<br />

on other animals, including<br />

rodents and birds. They have<br />

keen eyesight, hooked beaks,<br />

and feet with sharp, curved<br />

claws or talons. The group<br />

includes falcons, ospreys,<br />

hawks, vultures and eagles.<br />

Last year, <strong>NCC</strong> volunteers<br />

observed migrating golden<br />

eagles during an event in<br />

Alberta’s Crowsnest Pass. They<br />

also learned about raptors<br />

from local experts. In British<br />

Columbia, volunteers have<br />

helped conduct bird inventories<br />

to inform the development<br />

of <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation plans.<br />

You can sign up for one of<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s bird inventories across<br />

the country and learn more<br />

about birds of prey like the<br />

golden eagle. Apply that<br />

knowledge by downloading<br />

eBird or iNaturalist — two<br />

fantastic citizen science apps<br />

— and heading out to the field<br />

to collect important bird data.<br />

You’ll be contributing to a<br />

collective body of information<br />

on birds.<br />

GRASSLAND BIRDS<br />

Make fences<br />

safer for birds<br />

Hollow metal posts are often<br />

used in fences on Canada’s<br />

prairies. Since they are small<br />

in diameter and have smooth<br />

inside walls, the posts can<br />

create an unintended hazard<br />

for grassland songbirds. Birds<br />

can become trapped when<br />

they are looking for a hole to<br />

nest in, or when they perch at<br />

the edge of the uncapped post<br />

to explore what’s inside. Young<br />

birds are especially at risk,<br />

since they can easily fit into<br />

pipes. Once they are trapped,<br />

there is no way for them to<br />

climb out, and they die.<br />

The most critical times for birds<br />

getting caught in these hollow<br />

pipes is during migration and<br />

breeding seasons, when more<br />

birds are present and searching<br />

for shelter and homes. You can<br />

show your support for grassland<br />

songbirds, like McCown’s<br />

longspur, by helping <strong>NCC</strong> staff<br />

cap fence posts with tin cans<br />

and other recycled materials<br />

at the Old Man on His Back<br />

Prairie and Heritage Conservation<br />

Area in Saskatchewan.<br />

SHOREBIRDS<br />

Keep Canada’s<br />

shorelines clean<br />

Shorebirds sport long legs for<br />

wading in water or on mudflats,<br />

and long bills for feeding on<br />

hidden invertebrates. This group<br />

includes oystercatchers, avocets,<br />

stilts, turnstones, sandpipers,<br />

yellowlegs, snipes, godwits,<br />

curlews, phalaropes and plovers.<br />

The piping plover is an iconic<br />

yet endangered shorebird. In<br />

Atlantic Canada it breeds on<br />

sand and pebble beaches.<br />

You can support piping plovers<br />

and other shorebird species<br />

by participating in a shoreline<br />

cleanup this year. By volunteering<br />

to clean up marine debris<br />

and litter, you’ll enhance shoreline<br />

health and protect the areas<br />

where these birds nest and feed.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> hosts several shoreline<br />

cleanups each year, such as at<br />

Holman’s Island in PEI, Brier<br />

Island in Nova Scotia and Sandy<br />

Point beach in southwest<br />

Newfoundland.<br />

Songbirds, such as the<br />

endangered prothonotary<br />

warbler, are perching birds<br />

known for their diverse<br />

and elaborate songs. Many<br />

songbirds, including chickadees,<br />

woodpeckers, finches and<br />

nuthatches, are often seen at<br />

winter feeders. Sadly, many<br />

songbirds are disappearing,<br />

largely due to habitat loss.<br />

Join efforts to restore and<br />

maintain the health of native<br />

bird habitat by volunteering for<br />

a restoration project this year.<br />

Whether it’s digging in for<br />

a weed pull to remove invasive<br />

plants or rolling up your sleeves<br />

to plant a tree, you can help<br />

ensure songbirds continue to<br />

have safe places to nest and<br />

rear their young.<br />

In Ontario, <strong>NCC</strong>’s Conservation<br />

Volunteers have been supporting<br />

restoration work on Pelee<br />

Island — a site well known for<br />

its spring songbird migration<br />

— for more than eight years.<br />

This includes collecting seeds<br />

and planting native species on<br />

the property’s meadows and<br />

restored wetlands, creating<br />

prime habitat for birds.1<br />

Celebrate the return of migratory birds with<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>’s First Signs of <strong>Spring</strong>: Early Bird Edition<br />

photo contest, now until May 1. Snap these<br />

moments and share your photos on our<br />

Facebook gallery or on Twitter and Instagram<br />

using #<strong>NCC</strong>EarlyBirds. You could win one of<br />

our weekly outdoor gear prizes or even the<br />

grand prize: a $1,000 gift card. Upload your<br />

photos and vote for your favourites today!<br />

#<strong>NCC</strong>EarlyBirds<br />

natureconservancy.ca

BOOTS ON<br />

THE TRAIL<br />

Big heart country<br />

The Creemore Nature Preserve brings together locals<br />

with a shared passion for a natural gem in their backyard<br />

Creemore Nature Preserve<br />

Two hours northwest of downtown<br />

Toronto is the small Ontario town<br />

of Creemore, home to the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada’s (<strong>NCC</strong>’s) Creemore<br />

Nature Preserve. This 204-acre (83-hectare)<br />

property is loved by both locals and<br />

visitors alike.<br />

Home to majestic, mature sugar maple<br />

trees, a meandering, coldwater stream and<br />

small pockets of wetlands, this lush Niagara<br />

Escarpment forest shelters a variety of rare<br />

and at-risk species. The sounds of hairy and<br />

pileated woodpeckers echo through the trees,<br />

while the red-shouldered hawks soar in the<br />

skies above. At-risk wood thrushes and<br />

eastern wood-pewees also live here. The<br />

restored streams on the property support<br />

trout and other coldwater fishes, as well<br />

as various frogs and turtles.<br />

WILD WALK<br />

Over the years, <strong>NCC</strong> staff, along with volunteers,<br />

have installed new footbridges and<br />

improved trails on the reserve to provide<br />

recreational access for hikers and protect the<br />

surrounding habitat. There is a connected<br />

network of hiking trails that vary in difficulty<br />

and length, all of which have interpretive<br />

signage explaining the natural history and<br />

features of the area.<br />

As you walk through the forest and along the<br />

banks of the stream, you might spot the flash of<br />

silver from a jumping trout. Take the 100-metre<br />

Lookout Trail to see a former pond that is<br />

in the process of transforming into a marsh<br />

surrounded by new willows and dogwoods.<br />

Go early in the morning or in the late afternoon<br />

and you might spot a deer or coyote.<br />

LOCAL LOVE<br />

Known locally as “the Mingay,” after the family<br />

who originally owned and donated the land<br />

to <strong>NCC</strong>, the Creemore Nature Preserve is an<br />

important part of the community. This area<br />

was long inhabited by both Indigenous<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

6 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

peoples and more recent settlers. <strong>NCC</strong> started<br />

working on the property in 1997, but the trails<br />

through the forest were already well known<br />

to local nature enthusiasts. Creemore comes<br />

from the Gaelic “Croí Mór,” meaning “big<br />

heart,” and the town is true to its name in<br />

supporting and caring for this important local<br />

natural gem.<br />

Several partners have supported <strong>NCC</strong>’s work<br />

at the Creemore Nature Preserve, including<br />

Creemore <strong>Spring</strong>s Brewery, Nottawasaga Valley<br />

Conservation Authority, Fisheries and Oceans<br />

Canada, Gail Worth, Ian Cook and Carol Phillips,<br />

Bruce and Anne Godwin, DJ and Diane Wiley,<br />

and the Dichek family, in addition to many<br />

local families and the Government of Canada,<br />

under the Natural Areas Conservation Program.<br />

BACKPACK<br />

ESSENTIALS<br />

White trillium<br />

TRILLIUM: <strong>NCC</strong>. SARONGS: JUAN LUNA.<br />

TRAILS<br />

Maple Leaf Loop | moderate<br />

Length: 2.5 km Width: 1–3 m<br />

Surface: hard-packed dirt and rolling hills<br />

Highlights: Venture through a mature sugar<br />

maple forest and over stream crossings on<br />

this trail loop.<br />

Mingay Trail | moderate<br />

Length: 2.5 km Width: 1–3 m<br />

Surface: hard-packed dirt and rolling hills<br />

Highlights: Follow the trail to a restored<br />

stream and enjoy views from the lookout.<br />

Lookout Trail | easy<br />

Length: 0.1 km Width: 0.5 m<br />

Surface: hard-packed dirt and flat ground<br />

Highlights: Visit a restored pond to see new<br />

wetland plants, such as willows and dogwoods,<br />

grow and mature.<br />

Trout Trail | easy<br />

Length: 0.5 km Width: 0.5 m<br />

Surface: hard-packed dirt and flat ground<br />

Highlights: Follow the banks of a coldwater<br />

stream, keeping an eye out for trout.1<br />

Magic fabric<br />

Her beautiful and practical Indonesian sarongs are<br />

the most useful items that outdoor educator Jackie<br />

Pye takes into the great outdoors<br />

Sometimes, the simplest things<br />

go a long way when you<br />

are in the woods.<br />

Whether camping, hiking<br />

or canoeing, there are<br />

a few tools that I never<br />

leave behind — some<br />

of them technical, and<br />

some of them practical.<br />

On the practical side,<br />

some of the most useful<br />

things in my kit have been the<br />

sarongs I have collected in my work in<br />

Indonesia at the Green School. These<br />

affordable, reusable, multiuse fabrics<br />

serve not only as a wrap for<br />

a post-dip cover-up, but have<br />

many magical uses that<br />

make them a must-have<br />

on the trail. Some of my<br />

top uses for a sarong<br />

have been: as a blanket,<br />

an emergency sling,<br />

a sun shelter, a satchel<br />

bag, a strainer (for coffee<br />

or pasta), a blindfold for trust<br />

games, a towel, a belt, a scarf<br />

and an oven mitt.1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 7

Hidden in plain<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

TOP: RACHEL CARO. BOTTOM: THOMAS FRICKE.<br />

8 SPRING <strong>2018</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

With perhaps only 500 Poweshiek<br />

skipperlings left in the world, the<br />

Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve<br />

is giving this endangered butterfly<br />

a chance to survive the odds<br />

sight<br />

BY Susan Peters, writer and editor<br />

TKTKTKTKTKTKT<br />

They may be drab-brown<br />

and no bigger than a<br />

loonie, but Poweshiek<br />

skipperlings are rarer<br />

than pandas.<br />

On a sunny November day, Marika Olynyk checks the<br />

temperature above and below the snow at the Manitoba<br />

Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, just 80 kilometres southeast of<br />

Winnipeg. “Oh, that’s interesting,” she says. “It’s nine degrees warmer<br />

under the snow, close to the ground.” The site is home to some of the<br />

world’s last Poweshiek skipperlings, an endangered butterfly species<br />

currently in diapause — the insect equivalent of hibernation — and<br />

protected from the cold under a quilt of snow. “We think they’re near<br />

the soil. Some insects go into the soil in winter, but we don’t think the<br />

Poweshieks do that.”<br />

The “we think” is important. In the entire world, perhaps 500 Poweshiek<br />

skipperlings are left, with a significant portion found at the Manitoba<br />

Tall Grass Prairie Preserve. Once a common species, they’ve now become<br />

exceedingly rare: 10 per cent of the world’s population may be lying,<br />

frozen, a few feet from Olynyk’s weather monitoring station. Over the<br />

past 20 years, the population took a sharp, worrisome nosedive.<br />

Determining why the butterflies have disappeared, and how they<br />

can be recovered, is a team effort that stretches across the Canada–U.S.<br />

border, requiring universities, zoos, governments and researchers, including<br />

the Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>), to pool their knowledge, filling<br />

in the questions on this understudied species.<br />

“That’s the problem with endangered insects: they’re not on anyone’s<br />

radar. They’re fascinating if you see them up close, but no one’s going to<br />

see them up close,” says Olynyk wryly. She grew up in the country outside<br />

of Saskatoon, surrounded by nature — from the toad that came out of<br />

the sandy soil to plop onto the family’s deck when it rained, to the prairie<br />

cactus she loved showing off to a visiting relative. Passionate about<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 9

ecosystems, Olynyk originally studied environmental<br />

science, before earning her master’s<br />

degree in natural resources management.<br />

Now an engagement coordinator in <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

Manitoba office, her work includes research<br />

on the Poweshiek skipperling. “They’re not as<br />

charismatic as panda bears or polar bears,<br />

although those are great for drawing attention<br />

to environmental issues.” Poweshieks also<br />

don’t have marathon flights like monarchs,<br />

those magnificent long-range flyers found<br />

across southern Canada. So it’s perhaps<br />

less easy to admire the small, drab-brown<br />

Poweshieks, which are born and die in the<br />

same small patch of prairie.<br />

Last summer, Olynyk spent three weeks<br />

observing the Poweshieks, noting everything<br />

they did: observing what nectar plants the<br />

adults feed on (black-eyed Susans are a<br />

favourite), what they do in the rain (stop<br />

flying), how far they can fly (not far) and<br />

where they mate and lay eggs (Olynyk believes<br />

the perfect spot is between slightly drier<br />

terrain, where the nectar plants used by adults<br />

grow, and the slightly wetter land that supports<br />

the plants eaten by the caterpillars).<br />

Today, Olynyk is installing a new weather<br />

monitor and camera, and checking that the<br />

other instruments are functioning correctly.<br />

The camera, normally used to photograph<br />

wildlife like deer, will instead take a daily<br />

photo of the snow against a metrestick, to<br />

track its depth as winter progresses.<br />

Established in 1989, the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve is home to<br />

16 species at risk. Unfortunately, 99 per cent of this habitat has been lost.<br />

Today, the most urgent conservation<br />

Poweshiek skipperling, is to protect<br />

Protecting the prairie<br />

Once common across the American Midwest<br />

and adjacent Manitoba, Poweshieks are<br />

now found near Flint, Michigan, possibly in<br />

Wisconsin and in one place in Canada: the<br />

Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve. The<br />

preserve is over 12,000 acres (4,800 hectares),<br />

and owned by <strong>NCC</strong> and other partner organizations.<br />

The wind blows across flat, scrubby<br />

fields, interrupted by woods of bur oak and<br />

aspen. Here and there are old tractor attachments,<br />

abandoned by settlers who tried to<br />

grow crops, only to find the soil better suited to<br />

raising cattle. Ranchers and farmers conserved<br />

the native prairies in the area through grazing,<br />

haying and pasture-rejuvenating fire, to the<br />

delight of botanists who went looking for<br />

examples of tall grass prairie a century later.<br />

Established in 1989, the Manitoba Tall<br />

Grass Prairie Preserve is home to 16 species<br />

at risk, including two endangered butterflies:<br />

the spectacular monarch butterfly and the<br />

drab Poweshiek skipperling.<br />

With close to 200 Canadian species at risk<br />

documented on its properties, <strong>NCC</strong> is actively<br />

working to protect and recover these species.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> also manages and restores habitats for<br />

species at risk on some properties, with<br />

activities such as prescribed fires and invasive<br />

plant control.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> also works with local conservation<br />

groups and other landowners to develop<br />

management plans for properties. In the<br />

Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve, for<br />

example, cattle grazing and haying the<br />

grasses can help maintain open grasslands,<br />

benefitting the health of the prairie and<br />

local economy alike.<br />

“Canada has this very long history of<br />

recovering rare species, such as swift fox,<br />

white pelican and bald eagle,” notes Dan<br />

Kraus, <strong>NCC</strong>’s senior conservation biologist,<br />

adding that there have been three main<br />

causes of wildlife loss in Canada over the<br />

last 150 years: unsustainable harvest,<br />

pollution (such as DDT) and habitat loss.<br />

“We’ve made good progress on the first two<br />

problems,” says Kraus. “Today, the most<br />

urgent conservation action for species at<br />

risk is to protect and restore their habitats.”<br />

Tall grass prairies and the species that<br />

live there are in trouble, says Kraus. “We’ve<br />

lost 99 per cent of this habitat, and it’s<br />

critical we save what’s left.”<br />

CLOCKWISE, TOP RIGHT: JIM BRANDENBURG/MINDEN. THOMAS FRICKE. THOMAS FRICKE.<br />

10 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Helping hands<br />

In 2011, scientists who had become alarmed by<br />

the sudden disappearance of the Poweshiek<br />

skipperling came together for a conference in<br />

Winnipeg. Researchers and conservationists<br />

theorized about why the Poweshieks had<br />

blinked out of existence from the hundreds of<br />

sites where they used to live: gone in Minnesota<br />

and North Dakota, and cut down to only<br />

one spot in Wisconsin. Habitat loss was one<br />

of the biggest concerns, of course, since<br />

Poweshieks have very particular habitat needs.<br />

The other reasons for the butterfly’s<br />

disappearance remained a mystery: some<br />

areas were grazed by cattle, some weren’t,<br />

some had regular fires, some didn’t. Another<br />

possibility could be a changing climate — it’s<br />

possible that in a dry winter where the soil is<br />

left bare, or if the snow melts during a warm<br />

spell in February, the insects could die when<br />

exposed to -35 Celsius.<br />

The conference partners included<br />

representatives from Michigan, the world’s<br />

only other significant site of Poweshieks,<br />

where the butterflies live on the fringe of<br />

prairie wetlands unsuitable for farms or<br />

housing. “It’s probably not one single cause,<br />

but several things: chemicals, habitat<br />

“Because of the great partnerships we’ve<br />

built, we’re protecting more habitat for other<br />

species,” says Cuthrell. “In Michigan, there<br />

are two or three other rare butterflies in the<br />

areas that are being protected for Poweshieks.<br />

We have a little leafhopper that’s only in<br />

five sites in the world, but four of those sites<br />

also have Poweshieks.”<br />

Last summer, researchers from Winnipeg’s<br />

Assiniboine Park Zoo gathered eggs, trying<br />

to raise Poweshieks in captivity (six tiny<br />

caterpillars are spending the winter in an<br />

incubator set at -4 Celsius, before being<br />

thawed in the spring). Other scientists have<br />

studied genetic diversity to determine the<br />

extent of inbreeding. Poweshiek populations<br />

have become isolated into separate groups<br />

that can’t cross the road or ditch to mate with<br />

each other, let alone fly four states over. In the<br />

summer, for the brief period of two or three<br />

weeks when the adult Poweshieks are flying,<br />

biologists and volunteers gather at the<br />

Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie Preserve to survey<br />

Poweshiek skipperlings.<br />

The late fall day of checking weather<br />

monitors comes to an end at a site that<br />

Poweshiek skipperlings love, possibly because<br />

THREE AT-RISK TALL<br />

GRASS PRAIRIE SPECIES<br />

GREATER PRAIRIE-CHICKEN<br />

Now extirpated from Canada due to<br />

habitat loss and over-hunting, this<br />

species has not been observed in<br />

Manitoba for more than 30 years.<br />

Recovery efforts in Minnesota, just<br />

south of the Manitoba Tall Grass Prairie<br />

Preserve, are showing success. This<br />

species may soon expand its current<br />

range back into Canada.<br />

action for species at risk, like the<br />

and restore their habitats.<br />

TOP TO BOTTOM: TIM FITZHARRIS/MINDEN. GLENN BARTLEY/BIA/MINDEN. THOMAS FRICKE.<br />

destruction and climate change,” says David<br />

Cuthrell, a conservation scientist with<br />

Michigan State University. He’s concerned that<br />

Michigan is seeing more severe droughts and<br />

inconsistent winter temperatures. Plus, one<br />

theory is that newer chemicals in pesticides<br />

proven harmful to bumblebees and honeybees<br />

(the organophosphate compounds and<br />

neonicotinoids) could also harm Poweshieks,<br />

if applied incorrectly.<br />

The upside of unravelling the mystery of<br />

the Poweshiek skipperling’s decline is that<br />

the fight to save this one species may help<br />

researchers learn how to save other endangered<br />

butterflies, work across international<br />

borders and conserve habitat for other<br />

species at risk by saving the habitats they<br />

need to thrive.<br />

of all the black-eyed Susans growing there.<br />

Olynyk is quietly confident that she will see<br />

the humble brown butterflies again next year.<br />

“We have five good areas for Poweshieks,<br />

and we expect to see them in these areas in<br />

the summer. We still check some areas where<br />

there used to be Poweshieks, but we don’t<br />

expect to see them there anymore”<br />

In the spring, Olynyk and <strong>NCC</strong> staff will<br />

head out to the sites to collect the snowdepth<br />

cameras and weather data. They’ll<br />

gather and analyze the information on the<br />

2017–<strong>2018</strong> winter conditions at the Poweshiek<br />

sites. Any clues that can help unravel the<br />

mystery of this species and the conditions it<br />

needs to survive are invaluable in the race<br />

to ensure these butterflies continue to fly in<br />

Canada’s tall grass prairie.1<br />

BOBOLINK<br />

The male bobolink’s plumage resembles<br />

a tuxedo worn backwards. This mediumsized<br />

songbird has one of the world’s<br />

longest migrations, travelling over<br />

20,000 kilometres between southern<br />

South America, Canada and the northern<br />

U.S. each year.<br />

WESTERN PRAIRIE<br />

WHITE-FRINGED ORCHID<br />

This endangered orchid grows in wet<br />

meadows and prairies, and is pollinated<br />

by nocturnal sphinx moths attracted<br />

to its scent. <strong>NCC</strong> has secured habitat for<br />

more than 25 per cent of the global<br />

population of this species.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 11

SPECIES<br />

PROFILE<br />

Snapping<br />

turtle<br />

They're the armoured tanks of the natural world. With<br />

their mighty jaws and muscular build, snapping turtles<br />

are Canada’s largest freshwater turtles<br />

ROBERT MCCAW.<br />

12 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

SIZE AND WEIGHT<br />

Weighs up to 16 kilograms and usually grows to<br />

35 centimetres in shell length (but occasionally<br />

up to 50 centimetres).<br />

SHELL<br />

This robust species has a ridged, thick upper<br />

shell (carapace), which is tan, olive or black,<br />

and a long, studded tail. Its bottom shell<br />

(plastron) is small compared to that of other<br />

turtle species, leaving the snapping turtle’s<br />

limbs and neck exposed. The snapping turtle<br />

is unable to fully retract into its shell when<br />

threatened, which is why it snaps its jaws as<br />

a defense against predators.<br />

RANGE<br />

In Canada, this species is widespread — from<br />

southeastern Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia.<br />

Snapping turtles are still fairly common in<br />

eastern Canada, but less so in Saskatchewan<br />

and Manitoba.<br />

HATCHLINGS<br />

From late May to June, female snapping<br />

turtles build their nests in sandy soil. The<br />

number of eggs per nest varies widely, but<br />

a typical clutch contains 25–45 eggs. The sex<br />

of hatchlings is determined by the incubation<br />

temperature — males develop between<br />

23–28 Celsius, while females develop outside<br />

this temperature range.<br />

ALGAE<br />

Snapping turtles spend so much of their time<br />

in the water that algae grows on their carapace.<br />

They occasionally climb onto logs or rocks to<br />

bask in the sun, especially in northern areas<br />

where it is cooler.<br />

HELP OUT<br />

To help protect habitat for species such as<br />

the snapping turtle, visit giftsofnature.ca.<br />

More than a hard shell<br />

needed for protection<br />

Although snapping turtles have few<br />

natural predators due to their size, their<br />

numbers have declined because of the<br />

loss of their wetland habitat. They are<br />

particularly vulnerable to road mortality,<br />

because females often have to cross<br />

roads to find suitable nesting sites. Their<br />

reputation as aggressive, voracious<br />

predators has unfortunately also made<br />

them targets for persecution by people.<br />

Snapping turtles do not attack swimmers,<br />

and are only aggressive when provoked.<br />

They play an important role as scavengers<br />

and help keep our waters clean.<br />

Snapping turtles can live over 70 years,<br />

and only reach sexual maturity at 15 to 20<br />

years of age. As a result, any loss of<br />

mature individuals can impact the<br />

population. Roadside nests are at risk<br />

of being destroyed by traffic, and eggs<br />

and hatchlings are also vulnerable to<br />

being eaten by other animals.<br />

The snapping turtle is currently listed<br />

as a species of special concern under<br />

Canada’s Species at Risk Act.<br />

Snapping back for<br />

turtles at risk<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>),<br />

with support from our partners, launched<br />

the Carapace Project during the summer of<br />

2017. The project invites members of the<br />

public to report turtle sightings throughout<br />

Quebec. The data collected helps identify<br />

sites in need of conservation action and<br />

helps define hot spots for road mortality.<br />

To date, 856 turtle sightings have been<br />

reported on the website (carapace.ca), of<br />

which half were snapping turtles.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> conserves freshwater habitats that<br />

support species like the snapping turtle.<br />

Across Canada, <strong>NCC</strong> has conserved<br />

properties where snapping turtles occur,<br />

including in the Outaouais region, the<br />

Grand Marais de Bristol, Clarendon and<br />

Sheenboro natural areas in Quebec, the<br />

Interlake Natural Area in Manitoba and the<br />

Silver River property in Nova Scotia. In<br />

Ontario, <strong>NCC</strong> has restored wetland habitat<br />

on Pelee Island and in the Southern<br />

Norfolk Sand Plain. Snapping turtles were<br />

spotted using these new habitat areas<br />

almost immediately!1<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 13

PROJECT<br />

UPDATES<br />

3<br />

2<br />

WANT TO LEARN MORE?<br />

Visit natureconservancy.ca/where-we-work to learn<br />

more about other <strong>NCC</strong> projects.<br />

1<br />

1<br />

Protected: Island home<br />

of a nationally rare shrub<br />

YARMOUTH, NOVA SCOTIA<br />

BC NS<br />

Within an area 25 kilometres wide, on the<br />

southern tip of Nova Scotia, grows a unique<br />

perennial flowering shrub. A member of the<br />

aster family, eastern baccharis grows to about<br />

three metres tall. In fact, the entire Canadian<br />

population of this species, estimated at 3,000 plants, is found in<br />

and around the salt marshes of Lobster Bay, near Yarmouth.<br />

The Nature Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) recently protected<br />

a 61-acre (25-hectare) island habitat for this nationally threatened<br />

and rare plant. The newly conserved island in Lobster Bay is called<br />

Tete a Milie (Milie’s Head), named by the area’s Acadian settlers.<br />

Although found along the eastern coast of the U.S., in Nova Scotia<br />

the eastern baccharis is at the northern tip of its range.<br />

The island was entrusted to <strong>NCC</strong> by John Brett of Halifax, who was<br />

thrilled to discover eastern baccharis on the property about 15 years<br />

ago. “[Since I’m] an amateur naturalist, you can imagine how excited<br />

I was. It’s not every day you come across a large, prominent shrub<br />

that turns out to be the only member of its genus to be found in the<br />

entire country! And here it was, hiding in plain sight.”<br />

This dynamic environment, coupled with the shelter provided by<br />

Lobster Bay’s salt marshes and relatively mild climate, attracts a great<br />

diversity of wildlife: willets, bald eagles, ospreys, blue herons, kingfishers,<br />

harbour and gray seals, white-tailed deer, black bears, bobcats, minks,<br />

even the occasional porpoise and small whale. In the fall, many kinds of<br />

shorebirds feed on the mudflats before continuing their migration south.<br />

In winter, sea ducks, loons and mergansers shelter in Lobster Bay.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> has now completed two conservation projects in Lobster Bay,<br />

building on work by the Province of Nova Scotia to establish the nearby<br />

Tusket Islands Wilderness Area.<br />

Learn more at natureconservancy.ca/easternbaccharis.<br />

Harbour seal<br />

Tete a Milie is a drumlin: a rich mound of soil and rocky debris formed thousands<br />

of years ago by retreating glaciers, which has been further shaped by the tides.<br />

SEAL: NICK HAWKINS. EASTERN BACCHARIS, TETE A MILIE: ANTHONY CRAWFORD.<br />

14 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Partner<br />

Spotlight<br />

Thank you to our sponsors<br />

of the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada’s cross-country<br />

NatureTalks series in 2017.<br />

NatureTalks events engage<br />

Canadians in discussions that<br />

focus on urgent conservation topics.<br />

The NatureTalks cross-country<br />

series brings together multi-disciplinary<br />

panels for knowledge<br />

sharing, enhancing connections<br />

between people, nature and<br />

conservation.<br />

John Walters (Nancy Ferrier’s<br />

nephew) and his wife, Sylvia. When<br />

Nancy passed away, they became<br />

the executors of the estate.<br />

In 2017, the NatureTalks series<br />

visited 10 major cities across<br />

Canada and delved into various<br />

topics, including water, grasslands<br />

and natural capital. Thank<br />

you to everyone who joined<br />

us for an evening of thoughtprovoking<br />

discussion.<br />

2<br />

Keeping it all in the family: The Ferrier property<br />

GOUGH LAKE, ALBERTA<br />

In 1904, brothers John and Tom Ferrier sailed from Scotland to Canada to look for<br />

a homestead and to make a better life. They settled on the edge of Alberta’s Gough<br />

Lake, 125 kilometres east of Red Deer, where they built a wood shack with a tin roof.<br />

John and his wife, Agnes, raised their children on the farm through the Great<br />

Depression and two World Wars. After decades of drought, dust and hail storms, the<br />

Ferriers’ children saw the farm prosper.<br />

Recently, John Ferrier’s last surviving child, Agnes Isabelle Ferrier, known as Nancy,<br />

passed away and willed the land to <strong>NCC</strong>. The property contains wetlands and shoreline<br />

habitats that are essential for the mammals, grassland birds, shorebirds and waterfowl<br />

that live in and migrate through the region.<br />

AB<br />

3<br />

Loomer’s legacy: Picking up where he left off<br />

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

BRENT CALVER.<br />

Over two days this past September, the family of the late Dick Loomer, a former<br />

volunteer steward who passed away in June 2017, joined <strong>NCC</strong> Conservation<br />

Volunteers and staff at <strong>NCC</strong>’s Swishwash Island Nature Sanctuary. The group had<br />

assembled to recognize and carry on Dick’s important legacy of caring for this<br />

BC<br />

island, which perches in the mouth of the Fraser River.<br />

Located in the midst of one of Canada’s largest urban centres, Swishwash Island<br />

offers a safe haven for diverse wildlife, including coyotes, eagles, salmon and<br />

thousands of snow geese that use the island as a stopover spot during their flight<br />

south from the Arctic. After being taken over to the island on the Coast Guard’s<br />

bright red Zodiacs, the group planted 100 Douglas-fir seedlings, conducted a beach cleanup and cut Scotch<br />

broom, an invasive plant species. Watch a video of the event at natureconservancy.ca/swishwashsteward.<br />

NatureTalks will be coming to a city<br />

near you in <strong>2018</strong>! Stay tuned for more<br />

information, including dates, panel<br />

topics and speaker lineups:<br />

natureconservancy.ca/naturetalks.

FORCE FOR<br />

NATURE<br />

Home on<br />

the range<br />

On the Palmer Ranch in southwestern Alberta,<br />

ranching and conservation go hand in hand<br />

COLIN WAY.<br />

16 SPRING <strong>2018</strong><br />

natureconservancy.ca

Spanning the lush, vibrant grasslands of Alberta’s southern<br />

foothills, the Palmer Ranch is a place deeply rich in history,<br />

with family connections to the land tightly intertwined with<br />

the practice of ranching. It’s a place where cows graze on grassy<br />

ridges neighbouring Canada’s Rocky Mountains, which tower<br />

majestically in the background. The area still harbours wildlife<br />

species, including large carnivores, that once existed throughout<br />

the Northern Great Plains.<br />

JULIA PALMER.<br />

In 1999, co-owners Scott and Tom Palmer approached the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>) with the idea of building a lasting legacy<br />

on this land. It was <strong>NCC</strong>’s first large conservation agreement on the<br />

boundary of Waterton Lakes National Park. The project planted the<br />

seed for other collaborations between <strong>NCC</strong> and ranchers in the area.<br />

Scott’s daughter Julia is keen to continue her family’s legacy by<br />

taking the reins as the manager of Palmer Ranch. Read our interview<br />

with Scott and his eldest daughter, Julia, below.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>: Scott, why was it important for you to teach Julia about ranching<br />

and the rancher’s life?<br />

SP: “She came naturally to it. I wasn’t specifically teaching her things;<br />

she was just picking up on it. She had lots of exposure to different ways<br />

of approaching ranching, too.”<br />

JP: “One thing that was really special about growing up with my parents<br />

was that I never had to be a rancher. If I wanted to explore something<br />

else, I could. I just happened to love ranching, so mom and dad made a<br />

point of including me on so many different adventures. I wasn’t always<br />

helpful, and in fact may have slowed down the process, but I never felt<br />

like I was a hindrance. I had something to offer, and I could be part of<br />

the ranch. In ranching, you have this tie to a place that you watch, grow<br />

and change with. You can start to see your influence on it and also how<br />

it shapes you.”<br />

You have this tie to a place that<br />

you watch, grow and change with.<br />

You can start to see your influence<br />

on it and also how it shapes you.<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>: How have <strong>NCC</strong>’s conservation efforts on Palmer Ranch influenced<br />

your family’s ranching practices?<br />

SP: “<strong>NCC</strong> has been really important to us, ranching-wise. It’s given us<br />

a really nice base of grass to produce some grass-fed cattle — the way<br />

it used to be done [by ranchers in the past].”<br />

JP: “It’s been really exciting to have an organization like <strong>NCC</strong> to partner<br />

with, and it’s been great tapping into the knowledge network <strong>NCC</strong> has,<br />

such as rangeland health experts in the area. <strong>NCC</strong> has also been really<br />

open to our suggestions too, allowing us to work collaboratively on<br />

improving and enhancing this property.<br />

Palmer Ranch is a strong example of what can happen<br />

when ranchers and conservationists work together.<br />

“While we’ve absolutely made some<br />

mistakes at times, we’re recognizing and<br />

making the changes by using new strategies<br />

— that’s where <strong>NCC</strong> has been really important<br />

for us. Working with <strong>NCC</strong>, we’ve been able to<br />

develop off-site watering systems and change<br />

our grazing patterns by using electric fencing.”<br />

<strong>NCC</strong>: Julia, why is it important to you to continue<br />

your family’s legacy on Palmer Ranch?<br />

JP: “I love this place. If I could do one thing in<br />

my lifetime well, I want to leave it either intact<br />

or better than it was before. I want to contribute<br />

to a place, a landscape, that has meant more to<br />

me than I could ever put into words.<br />

“Ranching allows me to live here, and I really<br />

hope it is what I’m able to do for the rest of my<br />

life. I don’t have a family at the moment — my<br />

husband grew up on a sheep farm in Scotland<br />

and has a love of farming and agriculture as<br />

well — but we’re hoping to have kids. Perhaps<br />

they won’t want to be ranchers, but I hope they<br />

will always have an appreciation for nature<br />

and for the ranch.”1<br />

To read more about the history of Palmer<br />

Ranch and more from Julia and Scott, visit<br />

natureconservancy.ca/palmerranch.<br />

natureconservancy.ca<br />

SPRING <strong>2018</strong> 17

CLOSE<br />

ENCOUNTERS<br />

A chance to thrive<br />

By Senator Diane Griffin, former <strong>NCC</strong> program director for PEI<br />

From the nearby windows of a Jeep, we watched<br />

the gazelle gently clean her tiny newborn and then<br />

walk away. The newborn was too weak to move,<br />

so the mother came back and walked away again. Back in<br />

the Jeep, we were quietly cheering for the baby gazelle<br />

— “Get up! Get up!” — because we had seen lions and<br />

hyenas in the area, and knew the calf wouldn’t last long<br />

where it was, out in the open. The mother came back and<br />

this time the newborn tried to nurse — and the mother<br />

walked away again. Finally the baby was on its feet, moving<br />

on wobbly legs, and we breathed a sigh of relief, knowing<br />

its mother would soon find a good hiding place for it.<br />

I and a group of friends had been travelling across the<br />

Serengeti savannah, when our eagle-eyed guide and driver<br />

spotted a Thomson’s gazelle lying down in the grass.<br />

Although I’ve had many wonderful close encounters<br />

with wildlife, this experience on my African safari is one<br />

of the most memorable. I suppose it reminded me of the<br />

newborn calves I saw growing up on my family’s dairy farm.<br />

If not for the care of their mothers, and of course their<br />

human caretakers, they would not have survived. Growing<br />

up on a farm inspired me to study biology in university<br />

and I was fortunate to take courses in ecology — a new<br />

and exciting field in the 1970s. From my ecology professor,<br />

I learned about the interconnectedness of habitats and<br />

species, which led me to conservation and the Nature<br />

Conservancy of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>).<br />

While I have been fortunate to see wildlife in many<br />

places throughout the world, it never ceases to amaze me<br />

how rich Canada is in wildlife. Without habitat, there<br />

would be no wildlife — it is that simple. The work done<br />

by <strong>NCC</strong> helps to ensure that our country will continue to<br />

maintain habitat.<br />

Although we saw many other animals on that trip<br />

— and even had one of our camp chairs nibbled by<br />

a hyena outside our tent — it was that birth, and the<br />

vulnerability it exposed, that impressed me the most.<br />

I remain extremely proud of my work with and<br />

connection to <strong>NCC</strong>. We all have a role to play in conserving<br />

and caring for natural areas, to allow our Canadian<br />

species — including moose, mountain goat, Blanding’s<br />

turtle and many species of birds — the opportunity to<br />

be born and raised in the habitats they require to survive<br />

and thrive.1<br />

HEATHER COOK.<br />

18 SPRING <strong>2018</strong> natureconservancy.ca

Your passion for Canada’s natural spaces defines your life; now it can<br />

define your legacy. With a gift in your Will to the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada, no matter the size, you can help protect our most vulnerable<br />

habitats and the wildlife that live there. For today, for tomorrow and for<br />

generations to come.<br />

Learn more about leaving a gift in your Will at<br />

NatureConservancy.ca/legacy or 1-800-465-0029

YOUR<br />

VOICES<br />

Looking to the future<br />

“As a volunteer with the Nature Conservancy<br />

of Canada (<strong>NCC</strong>), I have been<br />

involved for several years with <strong>NCC</strong>’s<br />

work to conserve the unique landscape<br />

of Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2017,<br />

our family decided to donate a 243-acre<br />

(94-hectare) coastal property in Freshwater<br />

Bay, near St. John’s, to <strong>NCC</strong>.<br />

“This property is a peaceful place, with<br />

stunning views of the Atlantic Ocean,<br />

just minutes from the city. We were<br />

happy to provide the East Coast Trail<br />

Association with access to this land, so<br />

hikers could explore the area. Now we<br />

are looking forward to working with<br />

<strong>NCC</strong> to ensure this land is permanently<br />

protected and remains in its natural<br />

state for present and future generations<br />

to appreciate.”<br />

~ Rob Crosbie is an avid sportsman<br />

and well-known business leader who<br />

has been involved with <strong>NCC</strong> in Newfoundland<br />

and Labrador since 2009.<br />

Mess or meadow?<br />

“In my old neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, a church on a corner lot got<br />

torn down, to be replaced by townhomes. But before the property became<br />

a construction site, it stood vacant for a long time. Or rather, it stood unoccupied<br />

by people. Opportunistic wild things claimed it for their own.<br />

“In spring and summer, it became glorious; full of purple thistles and the goldfinches<br />

who thrive on them, sunflowers, orange daylilies, goat’s beard that<br />

formed seed pods like ghostly globes, blue tares, wavy grasses, creeping pink<br />

bindweed. Not only a joy to the eyes, the little meadow, as I called it, smelled<br />

green on the smoggiest days and hummed with insect chatter.<br />

“I knew that not everyone approved of the meadow, because I’d heard complaints<br />

about its resident skunk. 'Somebody should clean out that mess,' they said.<br />

“To me, the meadow was one of the neighbourhood’s pleasures and a testament<br />

to nature’s ability to transform a pile of rubble into a refuge. I fantasized<br />

about becoming wealthy enough to buy up every vacant lot in the city, just to<br />

leave it be. That didn’t happen, but pondering the fate of my meadow moved<br />

me to join in <strong>NCC</strong>’s efforts to open people’s eyes to the nature in their midst<br />

and to acquire and conserve plots of land across the country, some of them<br />

meadows destined to last!”<br />

~ Liz Warman has been a montly donor with <strong>NCC</strong> since 2009.<br />

Send us your stories! magazine@natureconservancy.ca<br />

GOLDFINCH: STEVE GETTLE/MINDEN PICTURES.<br />

NATURE CONSERVANCY OF CANADA<br />

245 Eglinton Ave. East, Suite 410, Toronto, ON M4P 3J1<br />

RE ID<br />

E18 A1