You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

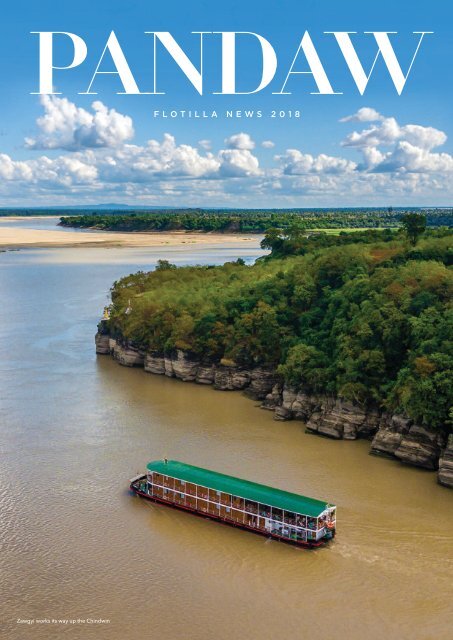

PANDAW<br />

F L O T I L L A N E W S 2 0 1 8<br />

Zawgyi works its way up the Chindwin

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

One of the really enjoyable things about my job<br />

is meeting our passengers on board the<br />

ships. My wife Roser and I base ourselves for<br />

the European winter in Burma and it’s great<br />

fun jumping on our bikes each morning<br />

from the office at Pagan and heading down to<br />

the port to do a quick tour and chat to our guests. That way we find<br />

out what people feel about what we do and how we do it.<br />

In Burma one thing that passengers feel very strongly about<br />

is the horrendous level of plastic pollution. This really is marring<br />

people’s experience in the larger towns and tourist centres, though<br />

off the beaten track, where we like to go, this is less of an issue.<br />

In response to this strong feeling we have tried to reduce<br />

the amount of plastic on board and give all passengers a<br />

complimentary aluminium water bottle that they can refill. This<br />

has proved a great success and though we still offer plastic water<br />

bottles no one wants them. And it’s good to see the crew<br />

volunteering to clean up river banks too. These may be small<br />

gestures in the scheme of things but word gets out and others<br />

follow.<br />

Burma has been much in the news. I do not want to sound<br />

defensive of the country I have been most closely associated with<br />

for over 30 years, but I will say that the country has experienced<br />

the longest running civil wars in the world today. The problems<br />

in the Arakan began in the early 1940s and there have been<br />

horrific incidents of ‘ethnic cleansing’ on both sides for the past<br />

seventy five years. Recent events were part of a long continuous<br />

history, only this time the UN made a report and the media made<br />

a story of it.<br />

Meanwhile life goes on as usual in the Irrawaddy valley<br />

where the majority of the population live and where we operate<br />

our ships. These troubles seem far from people’s minds and many<br />

of our Burmese friends and colleagues are not even aware of them.<br />

Inevitably visitor numbers will decline as a result of this<br />

media attention and livelihoods will suffer. However, as we argued<br />

during the period of devastating sanctions from the late 90s to<br />

early 2010s, we believe that by working in the country we can do<br />

better things. As with the last round of sanctions, it was the<br />

ordinary people who suffered, not the fat cats at the top.<br />

On a more positive note, we are excited to be building the 8th<br />

Pandaw Clinic at last that will act as the headquarters and<br />

diagnostic centre for the outlying village clinics. It is thanks to the<br />

support of our passengers that this has been possible, so thank you<br />

for that.<br />

On our smaller ship expedition cruises over 50% of the<br />

passengers have travelled with us before and some of them several<br />

times. There is quite a ‘Pandaw Community’ out there and in<br />

recognition of past and future loyalty we set up the ‘Pandaw<br />

2

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

Contents<br />

2 Pandaw Charity Update<br />

4 Pandaw <strong>News</strong><br />

8 Family and Friends Charter<br />

10 The Flowers of Yunnan<br />

12 An Eden of Islands<br />

16 Jungle Atlantis<br />

18 Burma’s Black Gold<br />

20 Greeneland meets Vietnam<br />

22 The Old King’s Ghost<br />

24 Remembering Hoa Binh<br />

27 Laos The Final Frontier<br />

28 First on the Mekong<br />

30 Expeditions Overview<br />

Members Club’ last year with a range of privileges, benefits and<br />

special offers. This has been a huge success with a surprisingly<br />

large number of people signing up.<br />

Interestingly we are seeing more and more multigenerational<br />

travel, with grandparents, children and grand children making<br />

family trips. We are also seeing far more private family charters.<br />

My own pet boat, the Kalay Pandaw, has proved a real hit with such<br />

family groups. Our son Toni, now nearly 21, grew up on these<br />

ships and there was never a dull moment whether off on a bike,<br />

playing football with the local kids on the sand banks or<br />

badminton free for alls with the crew.<br />

Another interesting trend we are seeing is a far younger<br />

demographic. River voyages once were strictly the preserve of<br />

retired folk. We are seeing far more people in their 40s and 50s,<br />

whether solo, sharing or travelling with their kids. This makes for<br />

a great social mix on board. I had a recent email from a passenger<br />

just back from Laos who told me that on their small ship there<br />

were ten different nationalities.<br />

Our coastal cruises on the Andaman Explorer got off to a<br />

very shaky start last season. Cruises had to be aborted first as a<br />

result of engineering problems and then because of issues with<br />

government licences. But now the Andaman Explorer is running<br />

well and Roser, Toni and I spent a very happy couple of weeks<br />

exploring the archipelago discovering more and more to see and<br />

do, not just of scenic and marine interest but also culturally.<br />

Our third ship for Laos will complete in late <strong>2018</strong> and this<br />

proves our most popular routing. The Laos Mekong is certainly the<br />

most spectacular and dramatic of the rivers we ply and a<br />

downstream run can prove an exhilarating experience as we surf<br />

over foaming white waters. Going upstream is slower but you get<br />

to see more! Laos is Asia’s best kept secret and lets keep it that way.<br />

Up in North Vietnam, the Red River, with its harsh climate<br />

(very hot or very cold and always very humid), begins with the<br />

excitement of cruising Halong Bay and ends in the foothills of the<br />

Tonkinese Alps. The ship also passes through the drab industrial<br />

suburbs of Hanoi. Passengers comment that they don’t mind this<br />

as it gives a real insight into real Vietnamese life and society.<br />

Indeed, on our Red River expedition there is a total immersion into<br />

Vietnamese culture. When we visited last November and witnessed<br />

the water puppet theatre acted out spontaneously in a village<br />

temple, far from the maddening tourist crowds, that seemed to<br />

encapsulate what Pandaw is all about.<br />

Ask any of our passengers what is so special about Pandaw<br />

and nearly all will say that yes the design of the ships, the comfy<br />

cabins, the good food, are all part of it. But the best part is the level<br />

of service and the warmth and friendliness of our Pandaw crews.<br />

This goes for all our teams in all six countries we work in. I am not<br />

sure why or how this happens, it just seems to be part of the<br />

magic. I hope that you agree.<br />

Paul Strachan<br />

Pandaw Founder<br />

3

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

mountain<br />

Bikes on<br />

all Ships<br />

Ω<br />

All Pandaw ships now<br />

come with Trek mountain<br />

bikes on board, so you can<br />

go off and explore on your<br />

own and keep fit at the<br />

same time. The exception<br />

being the Andaman<br />

Explorer, which has kayaks!<br />

In all six of the countries<br />

we sail through there is no<br />

better way to see the real<br />

country than by biking.<br />

O N T H E R I V E R S O F<br />

B U R M A A N D B E Y O N D<br />

B Y P A U L S T R A C H A N<br />

The Pandaw Story<br />

Ω<br />

In 1995 Paul Strachan invited an unlikely assortment of<br />

eccentrics and adventurers to join him in an untried new<br />

boat that would venture up the Irrawaddy River, the first time<br />

foreign tourists had ventured up the mighty Burmese<br />

thoroughfare since the Second World War.<br />

Against all odds, the trip was a huge success, word<br />

quickly spread and before Strachan knew it he was running a<br />

business in one of the world's least business-friendly<br />

environments. He named it the Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong> Company in<br />

honour of the Glasgow-based company that ran Burma's river<br />

transport when the country was an outpost of the British Raj.<br />

The company now trades under the name Pandaw, after the<br />

Clyde-built paddle steamer it restored in Burma.<br />

In turns hilarious, shocking, moving and often highly<br />

provocative, this book celebrates the 20th anniversary of the<br />

revived Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong> Company and the 150th<br />

anniversary of the founding of the original Irrawaddy <strong>Flotilla</strong>.<br />

The Pandaw Story also looks beyond Burma, at projects<br />

in Vietnam, Cambodia, India and Malaysia which met with<br />

many adventures and mixed fortunes. However, despite<br />

many challenges the company grew to be the largest river<br />

cruise fleet in South-East Asia and currently has fourteen<br />

ships in four countries.<br />

This lively, humorous and anecdotal account gives<br />

some insights into the trials and tribulations of doing<br />

business in Burma and in South-East Asia more generally,<br />

introducing many outrageous and some sinister characters<br />

from East and West.<br />

Mixing autobiography, colourful travelogue and part<br />

company history, it is a unique account of one of the most<br />

unlikely but extraordinary successes in today's travel industry.<br />

Paperback & digital ebook available at<br />

4

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

New Spa<br />

in Burma<br />

larger ships<br />

Ω<br />

Open on our larger<br />

ships on the Mekong and<br />

in Burma, our spas prove a<br />

welcome diversion when<br />

ships are cruising between<br />

the excursions ashore. We<br />

offer foot reflexology, back<br />

and shoulders, oil massage<br />

and in Cambodia the<br />

classic Khmer full body<br />

massage. We also offer<br />

manicures and pedicures<br />

by our experienced<br />

beauticians.<br />

Going Solo<br />

Ω<br />

The demographic of the solo traveller<br />

has changed dramatically over the past<br />

ten years. Pandaw has tailored several of<br />

its expeditions in response to this<br />

growing demand from independent<br />

explorers, offering adventure on the<br />

Irrawaddy, the Chindwin and the<br />

Mekong, within the secure environment<br />

of a small group of like-minded people.<br />

Often penalised by the travel industry<br />

with high single supplements, we prefer<br />

to look after our guests travelling alone<br />

by offering a cabin for single use at no<br />

additional cost on many of our river<br />

routes. We enjoy a loyal following of solo<br />

travellers who have the opportunity to<br />

safely discover the relatively uncharted<br />

territories of South East Asia, while<br />

appreciating the personal attention and<br />

casual ambience on board our small<br />

ships. Please check our website for<br />

current offers.<br />

5

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

Draft beer on ships<br />

cuts out garbage<br />

Ω<br />

We have introduced draft beer on our larger vessels.<br />

Not only do these brews taste better than canned beer<br />

but we no longer have the environmental issue of<br />

disposing of the empty cans. Responsible garbage<br />

disposal in developing countries can be challenging so<br />

we are constantly trying to reduce waste.<br />

In Burma we are offering Yoma, a pleasant light lager<br />

brewed with imported hops and the soft local water. It’s<br />

very crisp and rather welcome on a hot afternoon’s cruising.<br />

In Cambodia the Kingdom Brewery, the largest craft<br />

brewery in South East Asia supplies us with a very pure<br />

pilsner lager and a light IPA, both of which are as good as<br />

anything you will find anywhere.<br />

New Trip Books<br />

to cut paper waste<br />

Ω<br />

This season we published our trip book<br />

Mandalay Pagan Packet. All passengers<br />

plying this popular route will receive a<br />

complimentary copy in their cabin. The book<br />

contains detailed itineraries for those<br />

travelling between the two old Burmese<br />

capitals, whether on the seven, four or two<br />

night routings. There is detailed background<br />

on the history, culture and geography of the<br />

river stops we explore.<br />

The book also contains ship information<br />

and safety protocols. Passenger feedback has<br />

been very positive and there has been an<br />

environmental benefit too as we are no<br />

longer running the laser printers daily<br />

churning out endless itinerary and fact<br />

sheets. Next season we will roll the ‘trip<br />

book’ concept out to the Mekong and Laos.<br />

6

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

Aluminum Water<br />

Bottles replace plastic<br />

Ω<br />

Pandaw Burma takes delivery of a<br />

container holding 17,000 aluminium water<br />

bottles. These can be refilled at water coolers<br />

placed around the ships and help cut plastic<br />

pollution. All passengers get to take their<br />

bottle home as a souvenir and can continue<br />

to use it as they travel onward thereby further<br />

cutting plastic pollution.<br />

“<br />

Thanks to all the Pandaw crew for their<br />

ongoing effort in cleaning up the river<br />

banks and protecting their<br />

environment and also trying to make<br />

the local villagers aware of the damage<br />

plastic does to the fish and rivers so<br />

hopefully they will start to follow.<br />

7

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

FAMILY<br />

AND FRIENDS<br />

CHARTER<br />

Consider one of our smaller ships for a friends and<br />

family charter, your own Pandaw all to yourselves!<br />

Ω<br />

Work together with our experts to create<br />

your own itinerary and take your own time to<br />

explore the things that interest you, your family<br />

and friends. Work with our chefs and<br />

sommeliers to plan your dining experiences and<br />

wine selection.<br />

All our river ships come with mountain<br />

bikes and there is plenty for younger family<br />

members to do ashore or afloat.<br />

Consider the ten stateroom mega yacht<br />

Andaman Explorer that wends its way around<br />

the lagoons and atolls of the one thousand<br />

island Mergui Archipelago. Explore a unique<br />

marine world by Zodiac, kayak or snorkeling<br />

with your own family and a few close friends.<br />

Or take-off up the Irrawaddy or Chindwin<br />

on the gorgeous five cabin river yacht, the Kalay<br />

Pandaw. Designed and built by Paul Strachan<br />

for his family friends with its enviable owner's<br />

suite, the ultimate in river exploration.<br />

8

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM<br />

Under 18s Travel FREE<br />

Ω<br />

A special opportunity to share an educational family adventure during school holidays. Explore Asia in<br />

the comfort of a Pandaw vessel including daily excursions, cultural performances, movie nights and free<br />

mountain bikes to explore rural villages, temples and countryside.<br />

FIRST CABIN: Two adults pay full price<br />

SECOND CABIN:<br />

One or two children between the ages of 5 and 18 travel for FREE<br />

Check online for current offers and availability<br />

9

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

The Flowers of<br />

YUNNAN<br />

In the land of the plant hunters<br />

When in 2016 Pandaw became the first Western river expedition<br />

operator to break into Southern China, we were following – as befits<br />

our company heritage – in famous Scottish footsteps.<br />

Our Mekong: From Laos to China, the<br />

itinerary allows our passengers to<br />

experience the floral glories of Yunnan, the<br />

Southern Chinese province known as The<br />

Kingdom of Plants, once the hunting<br />

ground of George Forrest, one of the<br />

greatest of all the ‘plant hunters’. It is this opportunity to<br />

enter the horticultural Aladdin’s cave that Forrest first<br />

revealed over a century ago that makes this unique 14-day<br />

expedition unmissable by all serious gardeners.<br />

A highlight of our itinerary is the Xishuangbanna<br />

Tropical Botanical Garden, a vast garden and conservation<br />

centre with over 13,000 plant species. If any of the highland<br />

plants encountered there or on other expeditions along the<br />

route of the the RV Laos Pandaw and the new Sabei Pandaw<br />

seem familiar, that is because of the mass of botanical<br />

trophies that Forrest brought back to Britain in the early<br />

1900s. The specimens that were catalogued by the Royal<br />

Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh were to thrive in his native<br />

soil and proved hugely influential in determining how<br />

Britain gardens were developing for generations afterwards.<br />

It was Forrest’s strenuous, occasionally death-defying<br />

efforts in Yunnan that resulted in many of the varieties of<br />

acer, camellia, daphne, iris, primula and, of course, the<br />

rhododendrons that became the must-have status symbol of<br />

the Edwardian landed gentry.<br />

So who was George Forrest, and what was the<br />

attraction of Yunnan to pioneering plantsman?<br />

This southernmost province of China, like Northern<br />

Burma, Assam, Bhutan, Nepal and Tibet, lies in the<br />

‘temperate forest zone’, the great high plateau that extends<br />

across much of the bottom half of the Asian landmass.<br />

Crisscrossed by innumerable river systems, cooled by<br />

its high altitude and watered with heavy levels of rainfall,<br />

Yunnan sits in one of the most biodiverse areas in the<br />

world. By virtue of the relative remoteness and isolation of<br />

those high valleys, aeons of plant evolution have resulted in<br />

plant diversification and specialisation which is as extreme<br />

as that found on, say, the Galapagos Islands.<br />

Plant family trees have developed into numerous<br />

wonderful ways, developing elaborate family trees and<br />

subtle variations.<br />

While there may be as much, or more, plant<br />

biodiversity in the Amazonian rainforests or other tropical<br />

habitats, to European gardeners these beauties of the Asian<br />

temperate zone have the obvious advantage of proven<br />

hardiness outside the greenhouse.<br />

Essentially: if they can survive the high altitudes of the<br />

Himalayan foothills, they can survive a hard frost in an<br />

English (and even a Scottish) country garden. Thus for an<br />

ambitious Edwardian plantsman with an eye on supplying<br />

the green-fingered domestic market, Yunnan was Shangri-La.<br />

One of the first people to see the commercial potential<br />

was George Forrest (1873-1932) a humble chemist’s<br />

apprentice from Kilmarnock, who, by a series of random<br />

accidents, was sent to Yunnan in 1904 by an enterprising<br />

nurseryman from Exeter who contacted Edinburgh’s Royal<br />

Botanical Gardens (RBGE). This patron had heard tell of<br />

the extraordinary plant discoveries and seeds brought back<br />

by French missionary priests venturing into Yunnan from<br />

neighbouring Indochina.<br />

The fathers were reluctant to share their discoveries,<br />

at least with with Englishmen, but the RGBE put forward<br />

this young herbarium worker in answer to an appeal for a<br />

young explorer who might bring samples back to Blighty.<br />

Over his life, which was eventually to end on the<br />

Mekong in 1932, after a heart attack, Forrest made repeated<br />

visits to Yunnan, methodically collecting and recovering<br />

samples, building up a team of 20-30 trained ‘native’ plant<br />

hunters.<br />

Yunnan at that time was an exceptionally tough<br />

environment, the scene of horrific violence inflicted by<br />

Tibetan Lamas, then rebelling against Chinese<br />

encroachment. On his first visit, Forrest narrowly escaped<br />

an ambush in which the French priests who were<br />

accompanying him were perseveringly tortured in horribly<br />

imaginative ways. Forrest himself nearly died after various<br />

harrowing adventures, and after going into hiding, was<br />

reported dead back in Edinburgh, causing much to the<br />

distress of his family. When he did emerge, he was<br />

10

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/LAOS<br />

profusely apologetic for losing his carefully-amassed<br />

samples and botanical drawings.<br />

Forrest’s ordeal does not seem to have fazed him,<br />

as he was an exceptionally tough, and by some<br />

accounts, not a particularly attractive character,<br />

despite his Indiana Jones image. He made no attempt<br />

to his frank contempt for the gentlemen plant hunters<br />

of his generation, whom he considered dilettantes,<br />

and he proved adept at keeping them off his Yunnan<br />

“patch” as he returned time and time again over the<br />

decades to collect and catalogue samples.<br />

The gardening author and plantsman Ken Cox<br />

of the celebrated Glendoick Garden Centre near Perth<br />

has researched extensively on the plant hunters of<br />

that generation. Although his own grandfather,<br />

Glendoick’s founder, crossed swords with Forrest,<br />

Cox rates him as ‘in the top five’ of all the great<br />

British explorer-plant hunters of the last three<br />

centuries, the most famous of whom were Scots.<br />

Cox excuses Forrest’s unsympathetic behaviour<br />

on the grounds that he was a professional with a<br />

living to make, not a happy amateur, and anyway,<br />

great explorers tend to be hardy survivors rather than<br />

genial chaps. Where Forrest went Pandaw passengers<br />

can now follow, seeing the same glorious sights but in<br />

comfort, rather than at risk of life and limb.<br />

George Forrest<br />

11

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

AN EDEN OF ISLANDS<br />

The Explorations of Dr Helfer<br />

Felix Potter, author of the myeik Heritage Walking Tour, is a historian currently researching for a<br />

book on the region. In this article Felix describes the dilemmas facing the British East India Company<br />

on acquiring the Tenasserim region of Burma following the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824.<br />

Even before British troops stormed into Tenasserim in<br />

1824, the East India Company planned to give it away.<br />

They already understood what other conquerors had<br />

learned about the province: it is enticing to take, but<br />

expensive to maintain and impossible to defend.<br />

The financial drain of occupation made the matter<br />

urgent. Only two months after arrival, official correspondence confirmed<br />

that "The Governor General in Council adheres to his original opinion<br />

that supposing Tavoy and Mergui could be both held by our troops for the<br />

present & without hazard or inconvenience, the best way of eventually<br />

disposing of them would be to give them over to the Siamese... "At one<br />

point, Brigadier General Campbell was instructed to simply hand over<br />

Tenasserim “to any willing recipient from Bangkok to Phuket", or "to any<br />

Siamese army which may be assembled on that part of the frontier."<br />

Sentiments didn't change in the following years. Lord Bentinck,<br />

Governor-General of India, summed up the opinion in 1829, writing,<br />

"The expenditure far exceeded the income; no prospective benefit was<br />

held out as a counterbalance against present loss." He also feared<br />

rebellions and inevitable collisions with new neighbours. The diversion<br />

of troops even threatened to weaken other parts of the growing empire,<br />

particularly India and Singapore.<br />

The problem was finding someone to take it. Siam was reeling from<br />

decades of war with Burma and new conflicts in Laos and Cambodia.<br />

When the Company offered to exchange Tenasserim and the Mergui<br />

Archipelago for trade rights, Bangkok's divided palace was unable to<br />

respond. Long negotiations with the semi-independent state of Ligor (now<br />

Nakhon Si Thammarat) also went nowhere. The British even considered<br />

returning it to the Burmese, who refused to concede anything to the<br />

enemy for a province they considered rightfully theirs.<br />

Less known but equally influential was the arrival of British<br />

commissioner A.D. Maingy. When he sailed into Mergui on 29<br />

September 1825, he was appalled by what he found. The mainland and<br />

islands had been almost entirely depopulated, with upwards of 90% of<br />

the population having fled, been enslaved by Siamese and Malay raiders,<br />

or killed in a desperate guerrilla war that had waged intermittently for 65<br />

years. "It would be impossible to describe the distress and misery<br />

occasioned by the depredations of the Siamese," he wrote. "Since our<br />

conquest not a village a few miles distant from the Stockade has escaped,<br />

and at least one thousand and six hundred Inhabitants have been carried<br />

away."<br />

When Maingy saw Siamese prisoners in the Mergui jail, he ordered<br />

their chains struck off because they were ostensibly Company allies.<br />

Terrified residents immediately sent all women to hide in the forest while<br />

local men packed up their belongings. The commissioner was disturbed,<br />

and the prisoners were again incarcerated until he could investigate the<br />

situation.<br />

Very soon he concluded that for humanitarian reasons Tenasserim<br />

should not be ceded to either of the old combatants. He pleaded the case<br />

with emphatic reports to Lord Bentinck, and in turn to the colonial<br />

government in Bengal. To walk away meant abandoning people to reprisals<br />

or abduction, Maingy said, and almost certainly a resumption of war.<br />

Reluctantly, officials came to agree. Though its primary purpose<br />

12

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/ANDAMAN<br />

Mergui 1885<br />

Village Selon a l'Isle St Luke<br />

remained the exploitation of conquered territories, the Honourable<br />

Company was no longer equivalent to the very dishonorable organization<br />

of previous centuries. Since coming under supervision of the Crown and<br />

Board of Control in 1784, it had been forced to at least consider the<br />

welfare of its subjects in addition to profits. Its precarious political<br />

position was now tied to its reputation, which was under constant attack<br />

by enemies in Parliament, rival merchants, and a British public that had<br />

always been skeptical of its overseas shenanigans.<br />

Of course, that did not stop the directors from constantly grumbling<br />

about "our expensive and otherwise useless and mischievous occupation<br />

of the Tenasserim coast." The British continued flirting with the idea of<br />

cession, but after 1831 it was not seriously pursued. Even a brief rebellion<br />

in Tavoy did not deter them. The territory simply had to be made to pay<br />

for itself, which they realized must be done through development of its<br />

natural resources. The Company fetish for extensive taxation would never<br />

be sufficient given the poverty of the residents.<br />

Years passed while nothing paid the bills for thousands of troops<br />

and improvements that Mr. Maingy and other commissioners requested.<br />

The promise of pearls never panned out, for example, because few free<br />

divers could descend the ten fathoms necessary to gather wild oysters.<br />

Pearl farmers were brought from Madras, but costs exceeded profits and<br />

the project was abandoned. Expert divers from Malaya were hired in<br />

1928, though only after the council in Penang approved their demand to<br />

pay a "shark charmer" who could use spiritual powers to ward off fishy<br />

threats. The charmer apparently did his job — no injuries were reported<br />

— but this venture also proved unprofitable.<br />

On the mainland the situation was worse. Historically, Mergui had<br />

never been self-sufficient in rice, and the problem was exacerbated by<br />

Siamese raids. Merguians were unwilling to risk their lives and liberty to<br />

work paddies far from town. Mr. Maingy felt compelled to prohibit export<br />

of locally grown rice, because "had its exportation been allowed much<br />

distress would have prevailed at Mergui and among the poorer classes of<br />

this province." He also approved tax forgiveness and land title reforms to<br />

encourage agriculture, but results were meagre and did not produce a<br />

surplus to feed occupying Indian troops who became sick from poor<br />

rations. No teak grew in the southern forests, and deposits of tin and coal<br />

were difficult to access. Worst of all, a cattle epidemic in 1836 wiped out<br />

one-third of the livestock. Plans to develop the province carefully made by<br />

Mr. Maingy had to be abandoned in the aftermath. By then, the<br />

commissioner had retired, his health broken by overwork.<br />

HELFER IN THE ISLANDS<br />

The naturalist was indefatigable. Young, fearless, and driven by intense<br />

curiosity, he next set out to explore the Mergui Archipelago. On 28<br />

November 1837, Helfer departed from Mergui in several open boats and<br />

sailing canoes. His companions were twenty-five local Merguians who<br />

knew the islands mostly from rumours and furtive fishing trips.<br />

It seemed like a journey into Eden. Having been the haunt of pirates<br />

for sixty years, the archipelago was nearly pristine. Nature had reverted<br />

back to its virgin state in the absence of fishing, collecting and settlement.<br />

Only the Moken still lived there. Madame Helfer wrote, "He found the<br />

islands mostly uninhabited, but came sometimes upon remains of<br />

former settlements or temporary abodes of Malay pirates, who, before the<br />

time of British dominion,<br />

made these waters so<br />

dangerous. On the larger<br />

islands he observed<br />

scattered, deserted<br />

camping-places of the<br />

scanty nomad race, the<br />

Seelongs [Moken]. They<br />

are peaceful people<br />

without fixed abodes, who<br />

fly from hostile attacks<br />

into inaccessible<br />

mountains, or try to escape<br />

them in light boats, in<br />

which they glide rapidly<br />

Andaman islander 1892<br />

over the water."<br />

Like all Edens, this<br />

one was tainted. The Moken still in the islands were ones who had<br />

survived attacks of far more dangerous foes than pirates. In a tragedy that<br />

afflicted indigenous people across the earth, foreign pathogens caused<br />

epidemics well before most victims ever saw a foreigner. The 1820s were<br />

particularly deadly in the Mergui Archipelago, with mortality among<br />

some bands of Moken reaching 50% during initial waves of smallpox.<br />

Their elders, Helfer reported, only considered a child to be safe from<br />

disease after the sixth birthday. The doctor himself was unaware how<br />

these epidemics operated, as it was decades before the germ theory of<br />

disease was fully understood.<br />

In everyone's ignorance, Malay pirates remained the greater threat.<br />

Dr. Helfer described his first attempt to visit a band of Moken in the Blunt<br />

Islands, near Lampi : "My arrival at night terrified the defenceless natives,<br />

as they did not know whether I might be friend or foe, and feared an<br />

attack of Malays from the south. The women and children had fled into<br />

the interior, having concealed their small possessions, rice and cockles, in<br />

the thickets. Everything was in the greatest confusion; even the animals<br />

were scared at the unwonted visit, for dogs, cats, and cocks set up a shrill<br />

chorus."<br />

With patience, however, he convinced them that he meant no harm.<br />

Gradually, the people returned to the beach to meet the first European<br />

they had ever seen. Helfer was impressed, writing, "They behaved with<br />

remarkable civility and decorum." One wonders if the nomads said the<br />

same about him, as the Moken's previous experience with outsiders had<br />

been so traumatic. Helfer added, "By all who have to do with them,<br />

(Chinese and Malays) they are provided with toddy in the first instance<br />

and during the subsequent state of stupor, robbed of any valuable they<br />

possess. They gain however so easily what they want, so that they do not<br />

seem to mind much the loss when they come again to their senses."<br />

The Moken were as interested in Helfer as he was in them: "When<br />

they saw me drink coffee, and heard that I drank the black substance<br />

every day, they concluded this to be the great Medicine of the White Man,<br />

and were not satisfied until I gave them a good portion of it." Nearly two<br />

centuries later, we know their demands were entirely justified!<br />

The little flotilla left the Moken to continue its explorations. While<br />

Helfer sought scientific knowledge, his companions hoped to find other<br />

riches. For thousands of years, the Malay peninsula had been fabled as a<br />

13

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

land of treasure. Hindu legends called it Suvarnabhumi — the land of<br />

gold — and the dream would still influence masses of impoverished<br />

Indian labourers who ventured to British Burma during the rice boom of<br />

the early 20th century. Europeans were equally infatuated. Ptolemy called<br />

it Aurea Regio in the 2nd century C.E., and European cartographers<br />

labelled it ‘the Golden Chersonese’ until the 1800s.<br />

Of course the exact location was never given. The gold was said to be<br />

located somewhere between Sumatra and Pegu, a region large enough to<br />

keep fortune-hunters busy for centuries. Helfer listened to the rumours<br />

with amusement: "Since my first arrival at Mergui when it was known<br />

amongst the natives that I came into the country to look at all kinds of<br />

stones, plants and animals, I had at different times visits from Malays,<br />

Shans and Burmese, all of whom spoke of an island in the archipelago,<br />

which contains gold in great abundance. Marvellous stories were added to<br />

it, of neels [shrimp] who guard the treasure, of storms which arise when<br />

anybody dares to take the gold away. It was my intention this time to visit<br />

Cocks Comb Island<br />

this island, touching at others the same time which I had not yet seen.<br />

Where however this island was situated nobody knew in Mergui."<br />

His companions assured him that the treasure was always "beyond<br />

the next island." The doctor didn't mind. He diverted their enthusiasm to<br />

help collect hundreds of specimens of fish, shellfish, birds, mammals,<br />

insects, trees, grasses, and marine organisms. He took geological<br />

samples, observed the collection of edible birds nests, and contacted more<br />

bands of Moken. Eventually, the crew took him to a remote island where<br />

yellow metal glittered in a riverbed. Helfer was not deceived; it was only<br />

fool's gold.<br />

No one was discouraged. After a brief return to Mergui, Helfer and<br />

his crew continued their respective searches. On 27 February 1839, the<br />

Burmese guided him past the Bentinck Island group, which the doctor<br />

described as "weather- beaten rocks full of indentures, steep sides, and<br />

narrowed valleys. Their western side is generally exposed to the violence<br />

of the seas, their eastern side is surrounded by a smooth sea; the whole<br />

scenery altogether moved lake-like."<br />

Gold fever struck again: "The people had again to show me<br />

something particular occurring on one of the outer rocks of Observation<br />

Island, which is considered a talisman amongst the natives. I went in a<br />

small canoe to look at it, and found the crystals from pyrites whose<br />

bronze yellow made them appear to be gold."<br />

With the fever came the usual dangerous consequences: "The surf<br />

beating violently caused a great swell, our canoe was suddenly breached<br />

by a wave, shipped water, and filled instantly. We were about 30 yards<br />

from the shore and swam for it. The surf took hold of me and dashed me<br />

with violence against the rocks, which were covered with [molluscs and<br />

sea snails], and I was all bruised and cut by the knife-like edges and sharp<br />

spines of the shells. I succeeded however to climb up the rock before the<br />

next shock of the surf. Nobody perished, my Burmese people clung to the<br />

canoe, and others came over to our assistance. I was brought into my<br />

boat, out of which I could not move for the next three days. It was<br />

necessary to extract the spines . . . and I had about 50 fragments sticking<br />

in different parts of my body."<br />

After recovery during another brief visit to Mergui, Doctor Helfer<br />

visited King (Katan) Island, "where the French fleet waited in the last wars<br />

against the British stationed on the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal, for<br />

the purpose of intercepting the India men trading to China." Older people<br />

in Mergui could still remember these naval vessels and privateers, which<br />

made strategic use of the sheltered bay during the Revolutionary and<br />

Napoleonic Wars (1792 – 1815). Because the northeast monsoon closed<br />

down ports on the east coast of India from October to January each year,<br />

the French were able to dominate the Bay of Bengal months before the<br />

British navy could sail around from Bombay.<br />

"Numerous are the stories of the Frenchmen which the elder<br />

Burmese inhabitants have to tell of them," Helfer wrote, including tales<br />

of a stockade next to "French Watering Creek" on King Island. Helfer<br />

found no trace of their presence there, which of course did not deter his<br />

companions from renewing their search for treasure : "My people, like<br />

hundreds had certainly done before them, rummaged the whole place<br />

over, and would have continued so in the evening, had not the shrill<br />

piercing voice of the tigers in the vicinity driven them back to the sea<br />

shore."<br />

Unlike the island of gold, Mergui's tigers were no fable. Excellent<br />

swimmers, they had populated the entire archipelago and could ambush<br />

people from anywhere. Local people did not possess adequate weapons to<br />

fend them off. Helfer also noted that island tigers were more aggressive<br />

than mainland cats due to a scarcity of large game. "The western side of<br />

King's Island," he wrote, "is said to be the most dangerous in that respect<br />

and several well thriving Durian gardens had been abandoned on account<br />

of tigers." At least the doctor had no further trouble with rhinos, which<br />

also inhabited the archipelago.<br />

As his scientific collections continued, so did his exploration of<br />

legends. Helfer next took the boats to Kisseraing (Kanmaw) Island to<br />

investigate tales of a lost city: "This island though now entirely desolate<br />

of all fixed population is said to have been once very important, crowded<br />

with villages, the greatest part of the soil converted into fields yielding a<br />

superior quality of rice which was exported to the neighbouring countries.<br />

Whether in truth or at what time this was the case, and what was the<br />

reason of the total disappearance of the population, we possess no means<br />

to indicate at the present day. That the island was inhabited is proved by<br />

the numerous remains of Pagodas to be met within different parts of the<br />

island." To this day its archaeological history remains unsurveyed.<br />

More recently the island had been a notorious lair for Malay pirates<br />

who had so terrorized Merguians that people seldom ventured more than<br />

a few miles from town. After British occupation, a few fishermen were<br />

finally returning to Kisseraing to catch "the immense number of fish<br />

which migrate into the inner channels to deposit their spurm there, in<br />

millions." This abundance also attracted large numbers of cetaceans,<br />

giving its eastern side the name, "Whale Bay." Mercifully, the voracious<br />

Yankee whalers who were scouring the seas had yet to reach the Mergui<br />

Archipelago in 1839.<br />

Too soon, signs of the southwest monsoon hastened the end of<br />

Helfer's island adventure. He turned his tiny armada northwards towards<br />

Mergui town. The doctor took a last opportunity to visit Maingy Island,<br />

named for the man who had convinced the East India Company to protect<br />

the long-suffering residents of Tenasserim. Naturally, Merguians had<br />

established a small factory there to produce its most famous product:<br />

"[Maingy Island] is resorted to by fishermen from Mergui to prepare<br />

ngapee, this indispensable condiment to a Burmese in his cooking<br />

ingredients. I found a party of ten men lodged in a miserable shed on this<br />

island occupied with the preparation of this substance. The stench was<br />

dreadful to European olfactory nerves, so that I hastened away from this<br />

pestilential atmosphere as quick as the tide permitted . . ."<br />

One can only imagine Helfer's terrible suffering as he waited for the<br />

tide to allow his escape. The doctor soon had his ironic revenge, however.<br />

He began collecting "zoophytes," small marine creatures that he wished<br />

to examine back in town. Unfortunately, science turned rotten in the heat.<br />

14

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/ANDAMAN<br />

"When taken out of their element," he wrote, "the animals after death<br />

putrify and cause an insufferable stench. The Burmese, though their<br />

olfactory nerves are in other respects not at all delicate, declared that they<br />

could not bear it."<br />

After two days, all his crew was sick and had festering carbuncles on<br />

their legs. The doctor chose sympathy for his companions over dedication<br />

to craft and Company. He cast the creatures overboard. He was not too<br />

disappointed, though, because he had already collected vast amounts of<br />

specimens and data to process in Mergui. The plantation had also<br />

flourished under the care of the baroness, and the couple must have<br />

looked forward to their reunion.<br />

Doctor Helfer's reports are fascinating for their images of the forests<br />

and archipelago in their natural state. But they are also interesting for the<br />

portraits of the young European couple themselves. The doctor was a<br />

product of his education, which in the early 19th century was infused with<br />

racist theories of Caucasian superiority. He was hired by the notorious<br />

East India Company to help<br />

exploit its occupation of a<br />

foreign land. And yet, as he<br />

spent more and more time<br />

among local people, his<br />

curiosity and humanism<br />

steadily began to displace the<br />

racist ideas he had been<br />

taught.<br />

While in official reports<br />

he resorted to dismissing them<br />

as child-like, in his personal<br />

accounts he was filled with<br />

respect and sympathy. He both<br />

risked his life for his Asian<br />

companions and trusted them<br />

with his own.<br />

Madame Helfer likewise<br />

came to admire the people of<br />

Tenasserim. Though she<br />

arrived with the conviction that<br />

they needed Christian<br />

civilisation, she slowly found herself tempering that belief with deep<br />

respect for those around her. While her husband was away in the islands,<br />

the baroness even felt empathy for the thugs — convicted serial<br />

murderers transported from India — in whom she found humanity and<br />

decency deserving of forgiveness.<br />

HELFER IN THE ANDAMANS<br />

Doctor and Madame Helfer were two of a long list of remarkable people<br />

in the story of Tenasserim. That is why his next expedition was so tragic.<br />

After spending the rainy season developing the plantation with his wife,<br />

and after they resolved to stay in Mergui forever, he set off to explore the<br />

Andaman Islands. The islanders were known across the Indian Ocean for<br />

their hostility to outsiders. Sailing directions and tales of shipwrecks<br />

spoke of ferocious attacks by enraged men armed with spears and arrows.<br />

Helfer was cautious but undeterred. On January 29th, 1840, he bravely<br />

went ashore to make contact.<br />

At first, the reputation of the Andaman islanders seemed as fanciful<br />

as the land of gold. They were cheerful and provided wood and water in<br />

exchange for rice and coconuts. Helfer left in high spirits. The last words<br />

in his diary were, "These, then, are the dreaded savages! They are timid<br />

children of Nature, happy when no harm is done to them. With a little<br />

patience it would be easy to make friends with them."<br />

When he returned the next day, he was so confident that he ordered<br />

his crew to leave their weapons behind as a display of trust. Something<br />

went wrong. Different men met the party and lured them away from the<br />

beach. Suddenly, dozens of Andaman islanders emerged from the forest<br />

to attack. The visitors fled in panic to their canoes which overturned in the<br />

surf. They began swimming frantically back to the schooner while a rain<br />

of arrows issued from the angry men on shore. The wounded men<br />

reached the schooner, but not the young doctor from Prague. He took an<br />

arrow in the head and sank beneath the sea, never to be seen again.<br />

Madame Helfer was distraught. She attempted to continue in<br />

Mergui but the spell was broken. The widow soon returned to Europe,<br />

where she remarried and became Countess Pauline Nostitz. Even then<br />

Tenasserim held a fascination for her, as she dreamed of establishing a<br />

German colony on the far side of the world. Her brother, Baron des<br />

Granges, continued to manage thousands of areca and coconut trees on<br />

their land and even braved the tigers to set up a new plantation on King<br />

Island. After six years his health was destroyed, the orchards fell into<br />

disrepair, and authorities in Bengal conveniently forgot about the<br />

promises they had made to the late Doctor Helfer. Interest from the King<br />

of Prussia could not rescue the project either. The Countess was forced to<br />

seek compensation from East India Company directors in London, while<br />

her plantations were once again relinquished to tigers, rhinos, and the<br />

patient Tenasserim jungle.<br />

“<br />

Myeik Heritage Walking Tour book and website<br />

A historical guide to the fascinating town of Myeik in<br />

southern Myanmar. The guide includes a walking tour route<br />

map, color photos, and descriptions of 46 places of<br />

interest. Also included are discussions of Myanmar history<br />

in general, the Mergui Archipelago, and the British colonial<br />

era in which so many of Myeiks' buildings were constructed.<br />

The guide was created from archival research and the help<br />

of local residents.<br />

www.myeik-walking-tour.com<br />

Myeik Heritage<br />

Walking Tour<br />

by Felix Potter<br />

Available on Amazon<br />

Local Fishermen<br />

15

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

Jungle<br />

ATLANTIS<br />

Who built Angkor... and why?<br />

In the fourth of our occasional series on essential books for Pandaw passengers, Colin Donald recommends<br />

Charles Higham's The Civilisation of Angkor, the perfect primer for Cambodia's medieval metropolis.<br />

When Portuguese<br />

missionaries first<br />

encountered the lost<br />

city of Angkor in the<br />

1550s, they presumed<br />

it had to have something to do with the<br />

Romans ("supposed to be the work of Trajan"<br />

said one early history). Naturally they<br />

presumed these astonishing jungle-bound<br />

buildings had nothing to do with the primitive<br />

agrarian Cambodian society they observed<br />

around them.<br />

Ever since then scholars have been<br />

struggling to come to terms with the scale of<br />

the relics of the Khmer empire, a civilisation<br />

that flourished between the 800s and the<br />

1400s, under a succession of ruling dynasties.<br />

Much ingenuity has been expended on<br />

finding plausible explanations for the rise and<br />

fall of this race of architectural/engineering<br />

geniuses. Whole careers have been spent<br />

revealing the religious and political impulses<br />

behind the building of Angkor Wat, Angkor<br />

Thom, Preah Ko, Bantay Srei, and hundreds<br />

of other relics scattered over a 300-mile radius<br />

among the plains, hills and jungles of<br />

Cambodia and Thailand.<br />

It is not essential, of course, that Pandaw<br />

passengers encountering Angkor on our<br />

pioneering Mekong and Tonle Sap expeditions<br />

do their homework on the background to the<br />

civilisation of Angkor, but even getting a basic<br />

grip of the chronology will make their<br />

encounter with these great buildings more<br />

rewarding.<br />

A good place to start is with Charles<br />

Higham's The Civilisation of Angkor (2001), an<br />

authoritative synthesis of the recent<br />

archaeological scholarship on Angkor and the<br />

Khmers. Avoiding the temptation to be<br />

gushingly overawed by these vast buildings<br />

and reservoirs ("barays"), the book calmly<br />

considers current theories — mastery of floodplain<br />

irrigation, agricultural surpluses, etc —<br />

on how such feats of labour were organised.<br />

Prof Higham (b 1939) a British archaeologist<br />

based at Otago University in New Zealand, is<br />

a reliable guide through the centuries and<br />

dynasties of the Khmer empire, thanks to his<br />

intimate knowledge of the epigraphy (stone<br />

tablet-writing) through which the Khmers<br />

transmitted their political and bureaucratic<br />

activities to posterity, not to mention fine<br />

detail of endless land disputes, and chestbeating<br />

boasts about the smiting of enemies,<br />

notably the Chams of Vietnam.<br />

Higham's book shows that, like all<br />

official records, these stone chronicles can be<br />

dull and not wholly trustworthy. Because their<br />

intention is to magnify the god-like qualities<br />

of their commissioners, they only obliquely<br />

flesh out the remarkable human and<br />

managerial qualities of all of these latter-day<br />

pharaohs: Jayaravarman VII, Surayavarman<br />

II, Rajendravarman I, and many others<br />

carefully and comprehensively listed here.<br />

How did these great builder-kings motivated<br />

their workforce? Angkor Wat, the centrepiece,<br />

took 20 years to build, while European<br />

cathedrals (all smaller) took hundreds.<br />

There were slaves in Cambodia, but<br />

Higham asserts this was not exactly a slave<br />

state. Nevertheless it is hard to believe that<br />

terror was not part of the incentive package<br />

for the thousands who laboured away their<br />

lives; quarrying, shifting and assembling<br />

these intricate fantasies in stone, while the<br />

nearby Tonle Sap lake and its flood plain<br />

provided a surplus of fish and rice to<br />

minimise the need for more practical tasks.<br />

16

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/MEKONG<br />

“<br />

Higham is an archaeologist, most concerned with piecing together the chronology of this homegrown civilisation from the<br />

elite records that were carved on stone and the stylistic evidence contained in the buildings themselves. His priority is to list<br />

the various kings in order and what they built, which provides much-needed clarity over speculation on politics or sociology.<br />

Higham dismisses the 20th Century<br />

assumption, transmitted through the French<br />

colonial tradition and scholars like George<br />

Cœdès, which asserted that the Khmer<br />

aesthetic and technique was imposed on<br />

backward Cambodians by the then superior<br />

and more ancient civilisation of India. Recent<br />

archaeology, some of it conducted by the<br />

author, shows a clear line of development<br />

from Cambodia's prehistoric iron age leading<br />

into the Angkor period in the 800s. The<br />

many Indian touches, association of kings<br />

with Indian deities etc, represented the exotic<br />

tastes of the Cambodian elite, he claims, and<br />

not the impositions of domineering<br />

foreigners.<br />

But as the illustrations of relief carvings<br />

here show, Khmer art was not all formal<br />

representations of Hindu cosmology but also<br />

contained a jolly strand of folk art, which<br />

humanises Angkor and provides a brilliant<br />

contrast to the regal-religious pomp.<br />

Alongside a fair amount of smiting of<br />

neighbours and torturing of the vanquished,<br />

temple walls show that life in the Khmer<br />

empire provided plenty of time for leisure;<br />

forest picnics, riverboat frolics, games of<br />

chess and dancing girls. In contrast to the<br />

"frigid smile of power" as Norman Lewis<br />

described the depictions of Angkor's kings,<br />

there is folksy charm and wit in these relief<br />

carvings intended to suggest to posterity that<br />

there was more to life than dragging stones<br />

and digging stupendous rectangular<br />

reservoirs.<br />

This is a book about the builders of<br />

Angkor and what we know about who built<br />

what when. The author has less to say about<br />

the buildings-as-buildings, their symbolic<br />

religious meaning or their powerful mix of<br />

organic shapes and classical symmetry.<br />

Would-be visitors should reach for The<br />

Civilisation of Angkor for a summary of what<br />

we know as fact; which is a lot more than we<br />

used to but with much left to speculate about.<br />

That process will continue. Angkor has<br />

held onto its secrets since its mysterious<br />

abandonment during the 1430s and despite<br />

the great strides<br />

summarised in this<br />

book, will never<br />

entirely give them up.<br />

17

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

BURMA’S BLACK GOLD<br />

The Oil of the Irrawaddy Valley<br />

For more than two centuries oil has been produced from<br />

oilfields in the broad valley of the Irrawaddy River, long<br />

predating the birth of the modern oil industry in 1859<br />

when Edwin L Drake drilled his first successful well at<br />

Titusville, Pennsylvania.<br />

Following the relocation of the seat of government<br />

from Pegu to Upper Burma in 1635, a procession of British soldierdiplomats<br />

made their way up the Irrawaddy River to the court of the<br />

reigning king. Their observations on the oil production en route form a<br />

fascinating record.<br />

Yenangyaung (or Yenan Chaung), where they often stopped off, can<br />

be translated as ‘creek of stinking water' and in fact ‘yenan' became the<br />

Burmese word for ‘oil'. In 1755 George Baker and John North en route to<br />

King Alaungpaya's capital, Shwebo, found "about 200 families who are<br />

chiefly employed in getting Earth-oil out of pitts [sic]".<br />

Forty years later, in 1795-96, Major Michael Symes was leading a<br />

delegation from the Governor-General of India to the Court of Ava at<br />

Amarapura and gave a more detailed account of the Yenangyaung<br />

riverside export point:<br />

“<br />

"...the celebrated wells of Petroleum which supply the whole<br />

empire (of Ava) and many parts of India, with that useful<br />

product were five miles to the east of this place….The mouth<br />

of the creek was crowded with large boats waiting to receive<br />

a lading of oil, and immense pyramids of earthen jars were<br />

raised in and around the village... The smell of oil was<br />

extremely offensive. We saw several thousand jars filled with<br />

it ranged along the bank. Some of these were continually<br />

breaking, and the contents mingling with the sand..."<br />

Symes described the wellheads as holes about four feet square; he<br />

tested the depth of one well and found it to be ‘thirty-seven fathoms' (68<br />

m). He also described the recovery of the oil using an iron pot fastened to<br />

a rope which passed over a wooden cylinder which revolved on an axis<br />

supported by two upright posts; to raise the pot, two workers hauling on<br />

a rope ran down an inclined slope.<br />

Hiram Cox was the Rangoon Representative of the East India<br />

Company when, less than two years after Symes' visit to Yenangyaung,<br />

he inspected the oilfield in 1797 while on a mission to the Court of Ava at<br />

Amarapura. Cox counted 180 wells in one area and another 340 a short<br />

distance away; these are thought to have been the clusters of wells at<br />

Beme and Twingon respectively (Fig. 1). Topography helped determine<br />

the location of the hand-dug wells: the preferred locations were on small<br />

hilltops or hillsides where a level area could be excavated and where a<br />

slope ran away from the well to enable the workers to run downhill with<br />

their ropes while raising the digging-debris, or later the oil, to the surface.<br />

From the earliest observations of the Yenangyaung oilfield by<br />

foreign travellers to the eventual annexation of Upper Burma by Britain<br />

in the brief 1886 Third Anglo-Burmese War, the rights to produce oil at<br />

Yenangyaung were granted by the rulers of the Kingdom of Ava. Those<br />

rights were held by 24 individuals called ‘twinza'. It was a hereditary<br />

entitlement, and the system was called twinzayo.<br />

A well might take up to two years to dig, obviously depending on its<br />

depth and whether the digging was hard or soft – hard, calcareous layers<br />

were tackled by dropping a very large iron weight from the surface. The<br />

digger was lowered on a rope to the bottom of the well where he used an<br />

iron-tipped pole as his tool, the spoil then being raised to the surface in a<br />

basket on a rope.<br />

Because of the concentration of oily vapours at the bottom, as it<br />

deepened he could remain in the well for no more than about 30 seconds<br />

before being hauled to the surface. That is where the path sloping away<br />

from the well-head was important, enabling two or perhaps more men to<br />

run with the hauling rope to remove the digger from the well as speedily<br />

as possible.<br />

When oil was struck the same dangerous method was used to bring<br />

it to the surface, using iron buckets or lacquer-sealed baskets. The<br />

twinzayo system persisted long into British rule, operating alongside the<br />

drilling rigs of the oil companies.<br />

By 1896 when geologist G.E. Grimes was mapping the oilfields he<br />

noted that the diggers' lot had improved considerably, as they were now<br />

equipped with a ‘diver's helmet' into which fresh air was pumped<br />

manually down a flexible hose from the surface, enabling them to remain<br />

digging for up to an hour, reaching depths of at least 400 ft (122 m), but it<br />

remained a hazardous operation (Fig. 2). The risk of the well walls<br />

collapsing was lessened (but not wholly overcome) by installing wooden<br />

shuttering as digging progressed.<br />

Since 1858 there had been a small refinery at Rangoon, using<br />

Yenangyaung crude as feedstock and exporting products to Europe and<br />

India. By 1871 it was in financial trouble and its assets were bought by a<br />

group of Scottish businessmen who registered a new company in<br />

Edinburgh, the Rangoon Oil Company. Its local agent in Burma was<br />

Finlay Fleming & Co.<br />

The annexation of Upper Burma in the 1886 Third Anglo-Burmese<br />

War meant that the whole country, formerly the Kingdom of Ava, was<br />

now a part of British India administered locally by a Chief Commissioner<br />

in Rangoon. It was a milestone in the evolution of Myanmar's petroleum<br />

industry, ushering in the modern era. In that same year, 1886, David<br />

Cargill, principal shareholder of Rangoon Oil Company, sold it to another<br />

Scottish-registered company founded in the same year, Burmah Oil<br />

Company, which had technical links back home to the West Lothian<br />

shale-oil industry. Cargill thereby acquired an interest and became<br />

Chairman of the new company.<br />

By then another oilfield in the Irrawaddy valley was attracting<br />

attention, Yenangyat with its own crop of hand-dug wells, across the river<br />

from the ancient capital of Pagan (now Bagan). Without wasting any time,<br />

Burmah Oil applied for concessions over Yenangyat and Yenangyaung.<br />

Part of the commercial imperative behind Burmah Oil Company's haste<br />

to obtain concessions was that a number of the twinza's interests in<br />

Yenangyaung had passed by marriage to the former King, and by decree<br />

he had also acquired the right to purchase all of the twinza's own<br />

production; the result had been that the supply of crude oil to the<br />

Rangoon refinery had become erratic and threatened its viability.<br />

Concessions were granted to Burmah Oil Company and in January<br />

1888 drilling operations commenced using an American-style cable-tool<br />

percussion rig. The rights of the twinzas were protected in specified<br />

reserves, and by now they could sell their production to anyone, choosing<br />

in fact to sell it to Finlay Fleming & Co representing Burmah Oil, and so<br />

again an adequate supply of oil was able to be shipped to their Rangoon<br />

refinery.<br />

18

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/BURMA<br />

Fig. 1. Simplified geological map of part of the Irrawaddy valley, showing<br />

locations of the principal oilfields: Yenangyaung, Yenangyat, Chauk and<br />

Minbu. Other small fields are present up- and downstream.<br />

Fig. 2. Twinza well-digging team in the early 20th century, including the<br />

digger wearing a helmet into which air was pumped manually from the<br />

surface. Photograph from Pascoe (1912), "The Oilfields of Burma".<br />

Fig. 3. Yenangyaung oilfield in the 1920s. (Burmah Oil Company photo,<br />

courtesy of BP Archive).<br />

But Burmah Oil's early operations at Yenangyaung went through a<br />

difficult early phase. Security was a problem during the ‘pacification' of<br />

Upper Burma, with bands of dacoit attacking the encampments,<br />

sabotaging equipment and setting fire to the stored oil. Despite frequent<br />

setbacks, the introduction of mechanized well-drilling (first with cable-tool<br />

rigs in 1888 and rotary tools in 1911) allowed hundreds of wells and<br />

eventually over four thousand wells to be drilled on the Yenangyaung field,<br />

and oil production rose to a peak of 15,953 barrels per day in 1918 (Fig. 3).<br />

Meanwhile at Yenangyat, the local people were producing oil from<br />

hand-dug wells. Burmah Oil Company commenced drilling there in 1891<br />

and made their first discovery on the Yenangyat anticline in 1893. By the<br />

end of the 19th century production from the field was averaging 500<br />

barrels per day of a lighter and better quality oil than Yenangyaung.<br />

With new deep wells and even the helmet-equipped well-diggers<br />

contributing to production growth, Burmah Oil's refinery capacity<br />

needed to expand. Its original refinery was at Dunneedaw near Rangoon,<br />

but then a second was built at Syriam, south of Rangoon, which in due<br />

course became the company's main refinery. Later a pipeline from the<br />

oilfields to these refineries was built in 1908.<br />

The first two decades of the 20th Century saw the oil industry in<br />

Burma come of age: Burmah Oil Company had agreed a contract with<br />

the British Admiralty to supply fuel-oil bunkering; rotary drilling had<br />

been introduced in 1911; and geological science was being applied to<br />

field-development and exploration for new fields. Production was coming<br />

from the Yenangyaung, Yenangyat and Singu (Chauk) fields, and was<br />

beginning at Minbu. Total production was about 15,000 barrels per day.<br />

At the outbreak of the Second World War oil production averaged<br />

21,500 barrels per day from 3,800 wells. But the war brought oil<br />

production to a virtual standstill, and many of the wells and<br />

infrastructure were destroyed to deny them to the occupying Japanese.<br />

Reconstruction after the war brought fields back into production<br />

and, notwithstanding the nationalization of Burmah Oil Company in<br />

1963, new fields were discovered in the Irrawaddy valley, and production<br />

climbed to pre-war levels, peaking in the 1980s.<br />

But since then there has been a steady decline as older fields<br />

became depleted, and few large fields were discovered.<br />

In 1998 Burma took its place among the world's gas exporters and<br />

now gas is produced from several offshore gasfields and piped to<br />

domestic consumers and to export markets in China and Thailand, but<br />

gone are the days when Burma’s onshore oil production seemed the way<br />

to future propsperity.<br />

“<br />

Michael F Ridd<br />

Dr Michael F Ridd graduated from University College<br />

London in 1957, and joined BP as a geologist. During his<br />

subsequent career he lived and worked in Libya, Abu Dhabi,<br />

New Zealand, Alaska, Australia, Thailand and Singapore,<br />

ending his period with BP as Chief Geologist for their UK<br />

operations, based in Aberdeen. In 1985 he founded a small<br />

oil company, Croft, with Scottish backing, and built a<br />

portfolio of exploration and production interests including<br />

the North Sea, New Zealand, the US, and Burma. Since<br />

retiring in 1999 Mike Ridd has devoted himself to South East<br />

Asia geology, in particular seeking to unravel the complex<br />

plate-tectonic history of the region, on which he has<br />

published a number of papers and books. He lives in London<br />

and Scotland and is married to Mikiko, a musician.<br />

* This article is based on ‘Historical background to Myanmar's<br />

petroleum industry' by M. F. Ridd and A. Racey, Chapter 4 of<br />

‘Petroleum Geology of Myanmar,' Memoir of the Geological<br />

Society, London, 2015. Other source is: ‘Oil in Burma, the<br />

Extraction of "Earth-Oil" to 1914' by M.V.Longmuir, 2001,<br />

White Lotus, Bangkok.<br />

19

FLOTILLA NEWS - PANDAW.COM<br />

GREENELAND<br />

MEETS VIETNAM<br />

The Quiet American<br />

As part of our occasional series on the great reads in Pandaw’s onboard library,<br />

Colin Donald considers the classic novel of the dying days of L’Indochine Francais.<br />

For his fans Graham Greene<br />

was not just a novelist, he<br />

was a literary prophet who<br />

foretold the currents of 20th<br />

century history.<br />

Much of that perception rests on The<br />

Quiet American (1955), Greene’s middleperiod<br />

novel set at the height of the French<br />

Vietnam War. The book has been read as<br />

forewarning that the US’s attempt to<br />

prevent the reunification of Vietnam under<br />

Communist rule would – like the title<br />

character of the book – come to a sticky end.<br />

Temperamentally restless and fond of<br />

conflict, Greene served as a foreign<br />

correspondent for four winters in Vietnam<br />

during the 1946-1954 war, reporting for The<br />

Sunday Times and Le Figaro. He saw up<br />

close France’s agonies of wounded pride<br />

and moral compromise as it struggled in an<br />

inglorious colonial war against an elusive<br />

enemy, the Viet Minh. As related in his<br />

autobiography Ways of Escape (1980)<br />

Greene had good access to the highest<br />

levels of the French command and to Viet<br />

Minh agents, and was later to interview Ho<br />

Chi Minh.<br />

The Quiet American is the only lasting<br />

English-language evocation of the last days<br />

of l’Indochine Francais. It was an ugly<br />

episode, but Greene liked lost causes, and<br />

he finds a certain nobility in the plight of<br />

the French military.<br />

Set in 1952 while the Battle of Hoa<br />

Binh was still raging (see pg 24), the novel<br />

tells the story of a middle-aged and world-<br />

20

DISCOvEr mOrE vISIT - PANDAW.COM/VIETNAM<br />

weary English reporter called Fowler,<br />

whose 20-year-old Vietnamese girlfriend is<br />

won over by an idealistic and naïve young<br />

CIA officer called Alden Pyle, a rookie in<br />

the ways of the East but with misguided<br />

presumptions about the right path for this<br />

tinderbox country.<br />

This three-way dynamic, soaked in<br />

Greene-esque sexual jealousy and self-pity,<br />

seems be intended to represent the assault<br />

on inscrutable Vietnam, first by a decaying<br />

and self-serving colonial regime, then by a<br />

clumsily idealistic but hypocritical<br />

superpower.<br />

Fans of Greene will be familiar with<br />

the book’s portentous moral equivocating<br />

of which he was the 20th century’s leading<br />

adept. Published as it was at the height of<br />

the Cold War and of McCarthyism, it must<br />

seemed a full-frontal assault on Uncle Sam<br />

by a limey fellow traveller (which to be fair<br />

Greene was).<br />

The contrast of American good motives<br />

and bloody deeds is embodied in the<br />

character of Alden Pyle, the crew-cut<br />

Bostonian with a comic sense of chivalry and<br />

his academic anti-communist ideology.<br />

Through him, the novelist satirises the<br />

chances of building a “Third Force”<br />

alternative to colonialism or communism by<br />

promoting acts of random violence by<br />

unreliable and fractious South Vietnamese<br />

political partners.<br />

The novelist lays out the landscape of<br />

Saigon where most of the action takes place,<br />

and the North, where the hero goes to report,<br />

with a practiced journalist’s eye. There is<br />

vivid local colour, for example a visit to the<br />

bizarre Cao Dai sect in Tay Ninh near Saigon<br />

and the “Walt Disney” temple there. There<br />

are pages seemingly lifted from a war<br />

reporter’s notebook: a slaughter of villagers<br />

at Phat Diem, a terrifying Viet Minh night<br />

attack on a watch tower near Nam Dinh in<br />

the Red River Delta, a bombing raid on Lai<br />

Chau on the Chinese Border, the carnage of<br />

a horrific café bombing in Saigon.<br />

But there isn’t even much information<br />

about the reasons that the war against the<br />

Vietminh was happening, let alone the<br />

reasons why this sensually-described edifice<br />

of Frenchness had been imposed on the<br />

country for the preceding 70 years.<br />

Not then book to read for profound<br />

insights into Vietnamese culture or<br />

nationalist tradition, or even of French rule.<br />

Instead a vivid snapshot of Saigon at the<br />

end of the colonial era, and glimpses of the<br />

war in the North, suffused with the<br />

cynicism and melancholy that Greene fans<br />

will know and love.<br />

It took no great foresight for Greene to<br />

foretell that the French would lose the war<br />

(in any case they had surrendered before the<br />

novel was completed). The impressive piece<br />

of “prophecy” was to show in advance how<br />

the US would blunder in Vietnam in the<br />

pursuit of impossible ideals.<br />

It was Greene’s novel which first<br />

highlighted the improbability of success of<br />

an all-out hearts-and-minds approach,<br />

intended to embed democracy with civics<br />

lectures, hard cash, and napalm.<br />

Has time been good to The Quiet<br />

American? Yes and no. It gives us a vivid<br />

snapshot of Vietnam, a country of which<br />

most English-language readers are fairly<br />

ignorant, at a vital point in its history. Greene<br />

is a hugely professional and terse story teller,<br />

though his profundities and epigrams can<br />

seem pretentious or absurd.<br />

He is certainly adept at appealing to a<br />

certain type of male fantasy, albeit of a<br />

somewhat un-PC variety. Who wouldn’t want<br />