Toraja - The Art of Life with Death

Toraja people live in the central highlands of South-Sulawesi. Their most popular kind of parties are - funerals. A photo story about the art of life with death.

Toraja people live in the central highlands of South-Sulawesi. Their most popular kind of parties are - funerals. A photo story about the art of life with death.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

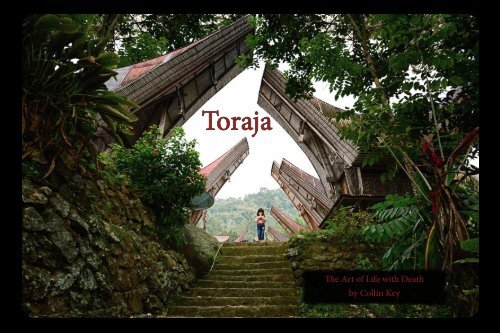

<strong>Toraja</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Death</strong><br />

by Collin Key

<strong>Toraja</strong> - <strong>The</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Life</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Death</strong><br />

This is Gonna. Gonna is a <strong>Toraja</strong> girl who lives in Tana <strong>Toraja</strong>, the central highland<br />

<strong>of</strong> southern Sulawesi. When I was Gonna's age this Indonesian island was still named<br />

Celebes and - from our point <strong>of</strong> view - marked the end <strong>of</strong> the world. In those<br />

days no visitors found their way into these tropical rain forests but a handful <strong>of</strong> anthropologists<br />

and some adventurers like the<br />

French Elisabeth Sauvy who, in 1934, published<br />

her travel diary "A Woman among Headhunters“.<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir stories usually told <strong>of</strong> bizarre<br />

rituals and terrifying death cults.<br />

Meanwhile, however, we have learned that<br />

the world is round and knows no end. Like<br />

children all over the world Gonna will grow<br />

up using a smartphone and the Internet. In<br />

school she will be taught mathematics and

foreign languages. Gonna is a little whirlwind full <strong>of</strong> energy and curiosity. She is definitely<br />

the child <strong>of</strong> a modern world.<br />

Yet her home is a special place, indeed. All these adventure stories were not entirely<br />

made up. <strong>The</strong> house Gonna lives in is named Maruang and its ro<strong>of</strong> is bent<br />

like a buffalo's horn. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> call this kind <strong>of</strong> house tongkonan. <strong>The</strong>y deeply cherish<br />

them for they are the dwellings<br />

<strong>of</strong> their forefathers. <strong>The</strong> title photo<br />

shows Goona beneath the ro<strong>of</strong>s <strong>of</strong><br />

her tongkonan as if under the protection<br />

<strong>of</strong> all her ancestors. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

may long be gone yet all her dead<br />

relatives are still close to her and her<br />

family and part <strong>of</strong> their life in a very<br />

real sense.<br />

Ne‘ Yayu is the eldest <strong>of</strong> the family.<br />

He permitted my son Robert and<br />

myself to stay in Maruang tongko-

nan for some time to start exploring the wondrous <strong>Toraja</strong> world from there.<br />

Often Gonna already awaits us when we return from our excursions in the late afternoon.<br />

Joyfully excited she jumps across the yard to greet us, eagerly waiting to see<br />

the new pictures I have taken <strong>with</strong> my camera. She escorts me to the veranda <strong>of</strong> our<br />

tongkonan where we sit down to view the images.<br />

Every scene is commented on and provokes explanations and stories which she keeps<br />

on telling us <strong>with</strong>out break - in a language that unfortunately I do not yet understand.<br />

Our lack <strong>of</strong> understanding is made up for, however, by her contagious enthusiasm. <strong>The</strong><br />

photos that attract her strongest attention are not, as one might assume, the images<br />

<strong>of</strong> landscapes, villages or even people she is acquainted <strong>with</strong> but those <strong>of</strong> graveyards,<br />

the rock cut tombs and burial caves <strong>of</strong> her ancestors.<br />

"tongkonan orang mati“ she exclaims - the dwellings <strong>of</strong> the dead.<br />

C<strong>of</strong>fins, skulls and bones - for Gonna such things bear no terror. Again and again<br />

she wants me to show these images to her.<br />

And thus we start <strong>of</strong>f our journey in the realm <strong>of</strong> the dead.

Tongkonan Orang Mati<br />

<strong>The</strong> ancestors welcome us as we enter the funeral grotto <strong>of</strong> Tampangallo. From a pile<br />

<strong>of</strong> skulls they look at us through empty eye sockets. <strong>The</strong> unprepared visitor cannot<br />

but remember the old stories <strong>of</strong> headhunting and other bizarre practices at this sight.<br />

Is this the way to treat your own dead relatives? Or rather your enemies?<br />

But the first impression<br />

<strong>of</strong> neclect is wrong. How<br />

much they are still cared<br />

for is revealed by a little<br />

detail which at first glance<br />

might even look a bit<br />

untidy: cigarettes lie scattered<br />

among the skulls. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

are gifts <strong>of</strong> the visitors who want their<br />

dead forebears to enjoy<br />

the beloved scent <strong>of</strong> cloves which is so characteristic <strong>of</strong> Indonesian cigarettes.<br />

Upon their death the corpses <strong>of</strong> this cave had been embalmed and laid into c<strong>of</strong>fins<br />

made <strong>of</strong> tropical woods. Many years later, however, once the mummies had finally<br />

decayed their osseous remains were taken out to make room for those yet to come...

<strong>The</strong>n we meet the dead in person: Around the corner they stand up on the wall<br />

looking down on us <strong>with</strong> round and marvelling eyes.<strong>The</strong>se are the tau-tau, life-sized<br />

wooden effigies <strong>of</strong> the deceased.<br />

Among them, to our great surprise - a Frenchman? Look at the second figure from<br />

right: Short trousers, moustache, fair hair neatly parted! Nobody could explain that<br />

effigy to me. It remains a riddle.<br />

<strong>The</strong> American anthropologist Kathleen Adams recalls in her book "<strong>Art</strong> as Politics"<br />

(2006 University <strong>of</strong> Hawai‘i Press) her first encounter <strong>with</strong> the tau-tau <strong>of</strong> Ke‘te‘ Kesu‘<br />

village. She was then accompanied by two young boys from the village:<br />

"While Siu picked up a bone and idly tossed it between his hands, Lendu nodded towards<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the effigies... 'This is Ne‘ Lele‘... We felt sorry for Ne‘Lele‘, to see her in rags,<br />

her breast poking out, so Mama gave her a sweater‘.“<br />

Lendu then introduced the anthropologist to many more <strong>of</strong> his ancestors all <strong>of</strong> whom<br />

he knew by name. To him this graveyard visit was rather like a family reunion.<br />

According to traditional belief the tau-tau are bombo dikita, visible souls. <strong>The</strong>y house<br />

the spirit <strong>of</strong> the deceased person. <strong>The</strong>ir relatives visit them regularly, <strong>of</strong>fering cigaret-

tes and even Rupiah notes. <strong>The</strong>y chat <strong>with</strong> them and keep them informed about the<br />

latest family affairs.<br />

Subsequently to the missionary activity <strong>of</strong> their former Dutch colonial rulers, however,<br />

95% <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Toraja</strong> population adopted the Christian faith. <strong>The</strong> predominantly<br />

Calvinist-coined church suspected these chit-chats <strong>with</strong> the ancestors to be a sign <strong>of</strong><br />

superstition, or, even worse, <strong>of</strong> idolism, and condemned the use <strong>of</strong> tau-tau. Priests<br />

would refuse to attend funerals if a tau-tau was part <strong>of</strong> the ceremony. Christian <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

countered that their interaction <strong>with</strong> the tau-tau was not due to their religious belief<br />

(aluk) but to tradition (adat), which they were not willing to give up. Moreover, even<br />

in Europe people would use photos <strong>of</strong> the deceased at funerals <strong>with</strong>out disapproval<br />

<strong>of</strong> the church.<br />

In a small restaurant specialized on dog meat we engage in conversation <strong>with</strong> a native<br />

priest. Being <strong>of</strong> Roman Catholic faith, he has no vital problem <strong>with</strong> effigies. Yet he<br />

rejects the excessiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> funerals: "<strong>The</strong>y may well financially ruin a family,<br />

yet most people rigidly maintain the practice. Well," he concludes, "my brothers and<br />

sisters are a bit stubborn at this." <strong>The</strong>ir obstinacy, I assume, may have contributed a<br />

lot to the survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> culture.

One <strong>of</strong> the most impressive<br />

sights in Tana <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

is that <strong>of</strong> the burial cliffs <strong>of</strong><br />

the village <strong>of</strong> Lemo. Numerous<br />

burial chambers<br />

are carved into the stone<br />

while the tau-tau stand on<br />

balconies silently gazing<br />

down into the valley.<br />

In other places the<br />

ancestors have been put<br />

behind bars as a kind <strong>of</strong><br />

preventive custody: <strong>The</strong>ft<br />

<strong>of</strong> tau-tau has turned into<br />

a serious problem since<br />

the antiquity market has<br />

realised their value.

<strong>The</strong> most bizarre rite <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> culture - at least from our alien point <strong>of</strong> view - is definitely<br />

ma'nene', the provision <strong>of</strong> fresh clothes to the deceased and their tau-tau. On<br />

that occasion c<strong>of</strong>fins are opened and the mummies taken out. Together <strong>with</strong> their living<br />

relatives they will celebrate a cheerful family reunion. <strong>Death</strong> is a part <strong>of</strong> life - to<br />

<strong>Toraja</strong> people this saying has an utterly tangible meaning. Neatly vested, the corpses<br />

will re-enter their graves while the day after their tau-tau will be tended to.<br />

We have been told that ma'nene' is being celebrated in the village <strong>of</strong> Londa but as we<br />

arrive the spectacular first day is already over and we will only see the tau-tau ceremony.<br />

Whether by mistake or deliberately, in order to avoid the rush <strong>of</strong> cameras, I do<br />

not know. In general visitors are welcome to<br />

all festivities <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Toraja</strong> and this includes<br />

tourists.<br />

In the same year 2015, American journalist<br />

Amanda Bennett has had the opportunity<br />

to attend a ma'nene' ritual. Her report and<br />

photos <strong>of</strong> the event can be found at National<br />

Geographic's online edition.

<strong>The</strong> Child Grave<br />

For their smallest family members, <strong>Toraja</strong> people have quite a unique kind <strong>of</strong> sepulchre:<br />

they bed them in the trunk <strong>of</strong> a large tropical tree.<br />

According to <strong>Toraja</strong> belief, the realms <strong>of</strong> gods, humans and spirits are entirely real<br />

places <strong>of</strong> the world and not abstract locations as heaven and hell are to modern Christians.<br />

<strong>The</strong> region to the east is the realm <strong>of</strong> the gods. Human beings live in the north.<br />

<strong>The</strong> west is the place <strong>of</strong> the deceased and spirits and ghosts dwell in the south. As a<br />

human is born, he passes from the east to the north. Once he is dead he will be in the<br />

west. By way <strong>of</strong> an extensive funeral his relatives guide the deceased to the southern<br />

land puya, the place where the spirits dwell.<br />

When a baby dies before it has grown milk teeth it is assumed that it has not yet completely<br />

arrived in the west before dying. Hence it will not be sent on that long journey<br />

to the south. Instead they hand it over to that large tree which will gently guide the<br />

little spirit back to the eastern realm <strong>of</strong> the gods.

<strong>The</strong> Funeral<br />

In the end his favourite buffallo was his doom. Something must have had startled<br />

the animal. A moment <strong>of</strong> inattention and the buffalo's horn hit him in a fatal blow.<br />

So we were told by Lisa, our guide, who accompanies us to the funeral. It is a morbid<br />

irony that numerous waterbuffaloes will now lose their life in return.<br />

Three months have passed since the accident. Three months which the deceased<br />

man has spent at home in his bed. He has been mummified to stop decay. Apart from<br />

this, his family has treated him like a person who has fallen ill - one that has moved<br />

away from the north but not yet reached the west.<br />

This is perfectly normal in Tana <strong>Toraja</strong>. Sometimes the deceased will stay home for<br />

years. A <strong>Toraja</strong> funeral lasts between three to seven days, in rare cases even longer.<br />

Hundreds <strong>of</strong> guests have to be entertained. Organizing such a celebration takes time.<br />

Gathering the necessary funds does as well. And many families are not ready to say<br />

good-bye too soon. <strong>The</strong>y keep on <strong>with</strong> their routines, give drink and food to the deceased,<br />

talk to him, let him partake in daily life.

Once the date for the funeral finally arrives the deceased<br />

is laid out in front <strong>of</strong> his family tongkonan and a lavish celebration<br />

is staged. Guests from all over arrive who are generously<br />

catered for. Days <strong>of</strong> great elation and pr<strong>of</strong>ound dolefulness<br />

follow.<br />

Visible for all the dead man has finally reached the realm<br />

<strong>of</strong> death. He is ready now to depart on his last journey to<br />

the southern land <strong>of</strong> puya where ghosts and spirits dwell.<br />

It is a difficult voyage and his funeral is conducted to safely<br />

lead him on his way. His celebrating kin and friends are his<br />

protective convoy so to say. <strong>The</strong> larger the funeral, the more<br />

guests and visitors, the safer will he reach his destiny.<br />

Having embraced the religion <strong>of</strong> the former Dutch colonial<br />

masters, as the majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> people has, he may then<br />

ascend from puya even further into the Christian heaven.

First to arrive on the scene are the pigs donated by the invited guests. Tied to long<br />

bamboo sticks they are still alive and certainly suspect no good. But their terrified<br />

squeaks are drowned by the voice <strong>of</strong> the emcee who announces through giant speakers<br />

and <strong>with</strong> dramatic intonation the incoming guests as well as their donations to<br />

the celebration. Each gift is neatly noted down in a large book for later reference, revenue<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers fill out the necessary forms.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n the invited families enter the square in long rows. Dressed in their finest black<br />

garments they circlet the heap <strong>of</strong> pigs <strong>with</strong> measured steps. <strong>The</strong>ir succession is strictly<br />

hierarchical, headed by the dignitaries and completed by the working people, as<br />

they are called nowadays. In former times, when the word and the practice had not<br />

yet been outlawed, they used to be called slaves. <strong>Toraja</strong> society is by no means egalitarian,<br />

but on the contrary feudal in structure, differentiating between nobility, free<br />

people and working men.<br />

Some men form a large circle to intone a dirge which like everything else is being<br />

drowned by the emcee's dramatic performance. More guests arrive while the ones<br />

who came before are <strong>of</strong>fered cigarettes and drinks. <strong>The</strong> whole scene seems like an<br />

odd medley <strong>of</strong> grief and exuberance. A vivid carneval <strong>of</strong> death.

In lieu <strong>of</strong> a pig or even buffalo we have <strong>of</strong>fered a carton <strong>of</strong> Indonesian clove cigarettes<br />

which, as our guide Lisa tells us, is the standard gift expected from tourists. Consequently<br />

we are invited to sit down on one <strong>of</strong> the bamboo platforms that have been<br />

constructed around the square to host the guests. <strong>The</strong> family already assembled there<br />

kindly makes room for us.<br />

Tea, banana chips and cigarettes<br />

are <strong>of</strong>fered to us, rice<br />

and pork cooked in bamboo<br />

tubes follow. Everyone<br />

is friendly and welcoming,<br />

people smile and willingly<br />

allow me to take photos. I<br />

am even invited to join one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the processions and <strong>of</strong>fer<br />

my sympathies to the mourning<br />

family.<br />

No doubt, <strong>Toraja</strong> people<br />

love their funerals.

<strong>The</strong> highlight <strong>of</strong> any funeral is the sacrifice <strong>of</strong> the buffaloes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> horns <strong>of</strong> the animals sacrificed will later be exhibited on the<br />

tongkonan's front pillar. <strong>The</strong>y will enhance the dignity and prestige<br />

<strong>of</strong> the house.<br />

Bori village is renowned for its stone circle. Menhirs have been<br />

erected in memory <strong>of</strong> great ritual celebrations well into the 19 th<br />

century. When visiting Bori we accidentally met a mourning family<br />

who had just finished the first day <strong>of</strong> funeral. After a nice<br />

talk and some portrait shooting to which they consented we were<br />

invited for the next day to attend the buffalo sacrifice.<br />

As we arrive at the scheduled time carrying the obligatory carton<br />

<strong>of</strong> cigarettes we find that our gift is uncalled-for today: Like<br />

all other tourists who show up we are summoned to pay our entrance<br />

fee.<br />

It would be totally wrong though to conclude from this that tourists<br />

are not welcome to funerals. On the contrary, as part <strong>of</strong> the<br />

visitors' crowd they contribute to the reputation <strong>of</strong> the tongko-

nan <strong>of</strong> the mourning family. <strong>The</strong> more<br />

guests the better the party.<br />

In 1986 the village <strong>of</strong> Ke'te' Kesu' - today<br />

a UNESCO world heritage site -<br />

saw the ten-day funeral <strong>of</strong> its renowned<br />

leader Ne' Duma. 300 kilometres away<br />

at Makassar airport tourist <strong>of</strong>ficials distributed<br />

pamphlets in Indonesian and<br />

English language drawing attention to<br />

the "truly unique <strong>Toraja</strong> event." Tens <strong>of</strong><br />

thousands <strong>of</strong> visitors followed the call<br />

to what turned out to be one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

memorable funeral celebrations ever.<br />

Being aware <strong>of</strong> the outsiders' disdain<br />

for animal slaughter, Ne' Duma's family<br />

urged Kathleen Adams, whom they<br />

Ne‘ Dumas tau-tau in Ke‘te‘ Kesu‘

considered an adopted daughter, to explain the cultural value <strong>of</strong> the massive buffalo<br />

sacrifice to the foreign audience. As an anthropologist, they expected her voice to be<br />

compelling.<br />

In fact water buffaloes are the animals most dear to the <strong>Toraja</strong>. <strong>The</strong>y are fostered all<br />

their life and don't have to do any farm work. <strong>The</strong> price <strong>of</strong> an average animal is about<br />

1,500 US dollar while top- rated<br />

buffaloes may reach the value <strong>of</strong><br />

a luxury car. Thus <strong>Toraja</strong> funerals<br />

are a great financial burden.<br />

"You spend your money on travelling,<br />

we gladly spend it for funerals,"<br />

I was told by a young female<br />

tourist guide. Incidentally,<br />

this is almost the same wording<br />

Kathleen Adams reports her <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

family to have used on the<br />

occasion <strong>of</strong> Ne' Duma's funeral.

Buffalo sacrifices are quite a bloody affair.<strong>The</strong> animals are killed by a clear cut through<br />

the throat. Seconds pass until they slowly conceive that something is wrong. Some<br />

buffaloes react at this point <strong>with</strong> a last defiant struggle, a moment not <strong>with</strong>out danger<br />

to the animal leader<br />

and the crowd<br />

<strong>of</strong> onlookers that<br />

is even warned by<br />

an English spoken<br />

announcement.<br />

Nevertheless,<br />

neither this nor<br />

their disdain for<br />

animal slaughter<br />

can prevent<br />

the tourists from<br />

pressing forward<br />

chasing for the<br />

best shot.

Tongkonan<br />

<strong>The</strong> tongkonan is much more than a mere house.<br />

Rather, it can be considered the focal point <strong>of</strong> the<br />

social structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong> society. A person's place<br />

in society is determined by his affiliation to certain<br />

tongkonans.<br />

This is <strong>of</strong> even higher importance than blood relationship.<br />

During her research Kathleen Adams<br />

was 'adopted' to the tongkonan <strong>of</strong> Ne' Duma <strong>of</strong><br />

Ke'te' Kesu' village. Years later she met a native<br />

<strong>Toraja</strong> at her American university. Both tried to<br />

make out if they had common 'family' ties. In order<br />

to do so, she reports, no names <strong>of</strong> people were<br />

referred to but solely names <strong>of</strong> tongkonans.<br />

<strong>The</strong> tongkonan takes centre stage in most rituals

and celebrations which in return enhance its reputation and thus the social prestige<br />

<strong>of</strong> the affiliated family. As in the case <strong>of</strong> funerals many <strong>of</strong> these festivities pose a considerable<br />

financial challenge to the family which can only be met by joint efforts. Even<br />

relatives that have taken jobs in faraway areas <strong>of</strong> the Indonesian archipelago - which<br />

is quite commonly the case - or who have migrated to foreign countries are expected<br />

to partake in and contribute funds to the wellfare <strong>of</strong> the homely tongkonan.

Thus the tongkonan strengthens the sense <strong>of</strong> community among people and by every<br />

ritual related to the house the family's bond <strong>with</strong> their ancestors is renewed. Each<br />

house has its unique lineage. <strong>The</strong> oldest and most prestigious tongkonans can trace<br />

their lineage back to the beginning <strong>of</strong> time itself, when the first ancestors descended<br />

from heaven on a huge ladder made <strong>of</strong> stone to settle in the tropical forest hills <strong>of</strong> Sulawesi.<br />

"Only if we remember who we are we will not forfeit our culture," Lisa claimes during<br />

our very first excursion. Lisa makes his living by explaining his world to the tourists<br />

he guides. It is obvious, however, that this topic matters to him personally. "I had to<br />

learn all the names and relations <strong>of</strong> six generations back in time. That certainly wasn't<br />

easy. Yet only if you know your ancestors you are able to retain your identity."<br />

<strong>The</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> 'identity' is quite in vogue in anthropological literature but rather rarely<br />

heard in common talk. <strong>The</strong> fact that Lisa uses the term might be seen as an indication<br />

that the vast anthropological work written about <strong>Toraja</strong> society influences that<br />

very society in turn. It changes the way people think about themselves.<br />

<strong>The</strong> typical <strong>Toraja</strong> village is made up <strong>of</strong> two rows <strong>of</strong> buildings <strong>with</strong> an empty square inbetween. <strong>The</strong> row <strong>of</strong> tongkonans<br />

is always facing north, the direction <strong>of</strong> human life, and is mirrored by the row <strong>of</strong> smaller rice barns (alang).

Tourism may have a similar<br />

impact, too.<br />

As mentioned before, <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

society is <strong>of</strong> feudal character.<br />

Traditionally, large<br />

funerals and buffalo sacrifices<br />

as well as the construction<br />

<strong>of</strong> a tongkonan used to<br />

be confined to the nobility<br />

and free men while ornamental<br />

decoration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

houses and use <strong>of</strong> tau-tau<br />

used to be a privilege <strong>of</strong> noble<br />

men only.<br />

In tourist marketing, however,<br />

all this counts as 'typical<br />

<strong>Toraja</strong>.' Nowadays most

<strong>Toraja</strong> <strong>of</strong> whatever status identify <strong>with</strong> these<br />

cultural symbols and feel proud <strong>of</strong> them. So<br />

does outside influence endanger the authenticity<br />

<strong>of</strong> tradition? Might it serve to turn genuine<br />

culture into mere folklore?<br />

Kathleen Adams rebuts these fears. In her<br />

book she argues that the adaptiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

society to new influences is actually a precondition<br />

to preserve their culture through<br />

the changes <strong>of</strong> time. <strong>The</strong>y face the transformations<br />

<strong>of</strong> their environment <strong>with</strong> self-confidence<br />

and adjust them to their needs. Only<br />

thus they were able to embrace the Christian<br />

faith <strong>with</strong>out losing the way <strong>of</strong> their ancestors.<br />

An old and notably splendid tongkonan. <strong>The</strong> many horns piled up<br />

on the front pole give evidence <strong>of</strong> many buffalo sacrifices and increase<br />

the prestige <strong>of</strong> the house. <strong>The</strong> floral ornaments are pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

the nobility <strong>of</strong> the family whose ancestors seem to have been active<br />

headhunters as well: human skulls are laid out on the high ledge.

<strong>The</strong> Wedding<br />

As fundamental as it seems death is <strong>of</strong> course not the only important topic in <strong>Toraja</strong><br />

life. Having been told <strong>of</strong> an upcoming wedding we mount our scooters and drive<br />

to the place. We go there on chance as we don't know anybody <strong>of</strong> the wedding party<br />

and have not been invited. But again we are kindly welcomed and invited to join the<br />

other guests on their bamboo platform. Our standard gift though is met <strong>with</strong> some<br />

sneering glances: cigarettes are obviously reserved for funerals and we make our carton<br />

quickly disappear in our bag.<br />

No doubt the wedding is a gaudy affair <strong>with</strong> rewarding scenes for a photographer. In<br />

general, however, the ceremony is rather formal if not to say stern. None <strong>of</strong> the jolly<br />

mood that is so vibrant at funerals. <strong>The</strong> dignified entry <strong>of</strong> the bridal couple is followed<br />

by some rather short performances <strong>of</strong> music and dance after which time slowly passes<br />

<strong>with</strong> seemingly endless speeches. Finally the guests are feasted <strong>with</strong> a fine meal.<br />

That photo <strong>of</strong> the standing bride and groom which I shot somehow reminds me - I<br />

beg your pardon - <strong>of</strong> the annual congress <strong>of</strong> the Chinese communist party.

Maruang Tongkonan<br />

When our guide Lisa asked his relatives at Maruang if we might live in the tongkonan<br />

for a while his request wasn not met <strong>with</strong> unanimous approval. Foreigners in the<br />

house <strong>of</strong> the ancestors? Finally Ne' Yayu, the eldest, took a decision and told Lisa that<br />

we were welcome in Maruang.

As is the case <strong>with</strong> many tongkonans nowadays, Maruang stands partly empty. <strong>The</strong><br />

lower level is occupied by Novita and her daughter Gonna while nobody resides on<br />

the upper floor. <strong>The</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> the family has constructed new houses to the sides <strong>of</strong> the<br />

old mansion <strong>of</strong> the ancestors which provide facilities for a life more comfortable.<br />

Thus we move to the upper floor which houses the traditional living quarters: a large<br />

central room <strong>with</strong> two smaller chambers to each side. <strong>The</strong> plain inside <strong>of</strong> the house<br />

contrasts sharply <strong>with</strong> its abundantly decorated facade.<br />

No one speaks English in Maruang,<br />

not even Novita who teaches<br />

Japanese at the local school. Gonna<br />

is the only one totally unimpressed<br />

by this lack <strong>of</strong> mutual understanding<br />

and she keeps on chit-chatting<br />

<strong>with</strong> us all day long.<br />

What a pity that I cannot write<br />

down her stories.

<strong>The</strong> kids <strong>of</strong> Maruang play ball<br />

Time for the ride to school

Lisa chatting <strong>with</strong> his<br />

relatives<br />

Grandmother roasting<br />

fresh c<strong>of</strong>fee

Thank you<br />

to Ne‘ Yayu‘ and the family<br />

<strong>of</strong> Maruang Tongkonan

<strong>Toraja</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Life</strong> <strong>with</strong><br />

<strong>Death</strong><br />

copyright 2016<br />

Collin Key