LOLA Issue Four

Issue Three of LOLA Magazine. Featuring the people and stories that make Berlin special: Moderat, Microdosing LSD, Yony Leyser, Julia Bosski, Notes of Berlin, Sara Neidorf and more.

Issue Three of LOLA Magazine. Featuring the people and stories that make Berlin special: Moderat, Microdosing LSD, Yony Leyser, Julia Bosski, Notes of Berlin, Sara Neidorf and more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

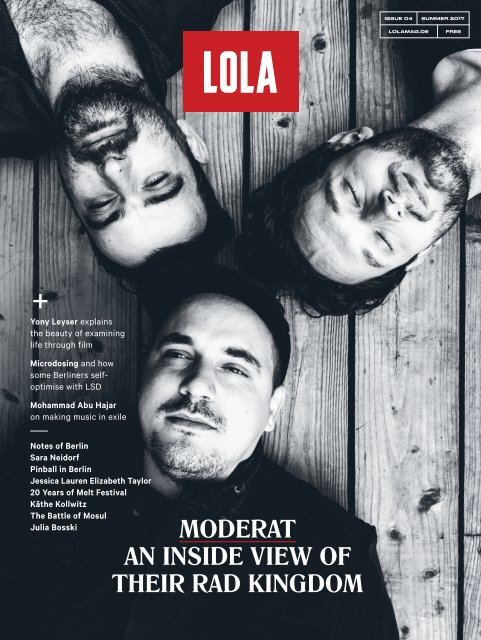

ISSUE 04 SUMMER 2017<br />

<strong>LOLA</strong>MAG.DE<br />

FREE<br />

+<br />

Yony Leyser explains<br />

the beauty of examining<br />

life through film<br />

Microdosing and how<br />

some Berliners selfoptimise<br />

with LSD<br />

Mohammad Abu Hajar<br />

on making music in exile<br />

Notes of Berlin<br />

Sara Neidorf<br />

Pinball in Berlin<br />

Jessica Lauren Elizabeth Taylor<br />

20 Years of Melt Festival<br />

Käthe Kollwitz<br />

The Battle of Mosul<br />

Julia Bosski<br />

MODERAT<br />

AN INSIDE VIEW OF<br />

THEIR RAD KINGDOM

10+ Commissioned Works by ABRA / Abu Hajar & Jemek Jemowit / Andreas Dorau / Balbina / Circuit des Yeux / Darkstar & Cieron Magat / Evvol<br />

Fishbach & Lou de Bètoly / Grandbrothers / Hendrik Otremba »Typewriter-Klangwelten« / How To Dress Well & Jens Balzer / Henryk Gericke »Too Much Future«<br />

Romano / Steven Warwick / »Sticker Removals – The Visual Anthropology of the Hype Sticker«<br />

70+ Concerts, DJ-Sets, Talks and Movies by Acid Arab / Alex Cameron Alexis Taylor / All diese Gewalt / Andrra / Anna Meredith / ANNA VR / Arab Strap / AUF<br />

Barbara Morgenstern / Bunch of Kunst / Boiband Christine Franz & Simone Butler / Cristian Vogel / Daniel Meteo / David Laurie & Simon Price / Decadent Fun Club<br />

Emel Mathlouthi / Erobique / Friends of Gas / Gaika / Gudrun Gut / Happy Meals / Hello Psychaleppo / Idles / Iklan feat. Law Holt / Islam Chipsy & EEK Jacaszek<br />

Jakuzi / Jeff Özdemir, F.S Blumm & Friends / Jessica Pratt / Lady Leshurr / La Femme / Lenki Balboa / Let’s Eat Grandma / LeVent / Liars / Little Simz / Lucidvox<br />

Manuela / Masha Qrella / Michelle Blades / Miss Natasha Enquist / Monika Werkstatt / Noveller / Oligarkh Oranssi Pazuzu / Paul Williams, Rob Young & Rob Curry<br />

Piano Wire / Prairie / Riff Cohen / Ritornell / Rouge Gorge / Shirley Collins / Sophia Kennedy / Smerz / Strobocop / Soft Grid / Tasseomancy / Throwing Shade<br />

Tobias Bamborschke / T.Raumschmiere / Young Fathers and many more …<br />

23 – 25 August 2017<br />

Kulturbrauerei Berlin<br />

pop-kultur.berlin

Summer 2017<br />

Editorial<br />

A YEAR IN THE LIFE.<br />

Here we are, one year on. It’s been a<br />

rollercoaster ride of emotion and<br />

thrills. I’m going to turn this editorial<br />

letter into a long list of gushing thank<br />

yous, because the truth is that without the<br />

amazing hard work, dedication, creativity,<br />

talent and love of all the people you can see<br />

on the masthead, <strong>LOLA</strong> simply wouldn’t<br />

exist, and everything that’s happened in<br />

last year wouldn’t have happened.<br />

Take Marc Yates, our esteemed Editor,<br />

for example. If only you could see the<br />

amount of graft, toil and expertise Marc<br />

puts into making sure each issue of this<br />

magazine is the best it can possibly be. His<br />

attention to detail always amazes me, as<br />

does his capacity to tolerate my crazy ideas.<br />

The title of Associate Editor doesn’t do<br />

Alison Rhoades justice. Alison has provided<br />

her expertise and support to every area<br />

of <strong>LOLA</strong>, and her contributions are phenomenal.<br />

Every piece you read is improved<br />

by her touch, and so many of the editorial<br />

concepts are the result of her work.<br />

Linda Toocaram deserves a special<br />

mention for always being an absolute rock<br />

of a Sub Editor, for working to our insane<br />

deadlines and for schooling us in the art<br />

of perfect grammar. A huge shout out for<br />

Stephanie Taralson, who goes above and<br />

beyond her role as contributor to help with<br />

editing and proofing. Maggie Devlin has<br />

also become a big part of <strong>LOLA</strong> since we<br />

met two issues ago, and her editorial contributions<br />

are completely invaluable.<br />

For the writers, I have to single out Alex<br />

Rennie, who has contributed something<br />

incredible to every single issue, and who<br />

always throws himself full-force into each<br />

article he writes. There have been so many<br />

great features written this last year, so huge<br />

respect and thanks go to Stuart Braun,<br />

Emma Robertson, Hamza Beg, Ryan Rosell,<br />

Dan Cole, Anna Gyulai Gaal, Jack Mahoney,<br />

Gesine Kühne, Alexander Darkish, Jessica<br />

Reyes Sondgeroth, Nadja Sayej, Jana Sotzko,<br />

Hanno Stecher and Jane Fayle.<br />

As for the visual impact of the magazine,<br />

I have to give the biggest thanks to Robert<br />

Rieger and Viktor Richardsson. They have<br />

both helped to shape the visual identity of<br />

<strong>LOLA</strong> in amazing ways, and are a joy to work<br />

with. Of course, endless thanks to all the<br />

photographers who have contributed to the<br />

magazine: Marili Persson, Justine Olivia Tellier,<br />

Julie Montauk, Zack Helwa, Fotini Chora,<br />

Soheil Moradianboroujeni, Roman Petruniak,<br />

Shane Omar, Tyler Udall and David Vendryes.<br />

Outside of the magazine, an enormous<br />

thank you has to go to Allan Fitzpatrick for<br />

designing and continuing to develop the<br />

<strong>LOLA</strong> website; it’s a thing of beauty. Also to<br />

our Editorial Assistant Erika Clugston for<br />

the endless help, especially with managing<br />

our social media presence and increasing<br />

the office smile count immeasurably! For<br />

all of the help in running our events, Emma<br />

Taggart has to get a special shout out.<br />

Finally, thanks to everyone who has<br />

supported us to date – BIMM Berlin, BRLO<br />

Beer, Crazy Bastard Sauce, Garvey Studios,<br />

Goethe Institute, Melt! Booking, Mobile<br />

Kino, Our/Berlin Vodka, Puschen Concerts,<br />

Studio 183 and Universal Music.<br />

And of course, thanks to everyone who<br />

has been featured in the pages of <strong>LOLA</strong>.<br />

You are the reason we do what we do. Our<br />

immigrants’ love of Berlin shines on. Jonny<br />

Publisher &<br />

Editor In Chief<br />

Jonny Tiernan<br />

Executive Editor<br />

Marc Yates<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Alison Rhoades<br />

Photographers<br />

Soheil Moradianboroujeni<br />

Shane Omar<br />

Viktor Richardsson<br />

Robert Rieger<br />

Justine Olivia Tellier<br />

Illustrator<br />

Patricia Tarczynski<br />

Writers<br />

Hamza Beg<br />

Stuart Braun<br />

Erika Clugston<br />

Maggie Devlin<br />

Gesine Kühne<br />

Alex Rennie<br />

Ryan Rosell<br />

PR & Events<br />

Emma Taggart<br />

Special Thanks<br />

Alex Brattig<br />

Sven Iversen<br />

Ben Jones<br />

Ann Kristin<br />

Sarie Nijboer<br />

<strong>LOLA</strong> Magazine<br />

Blogfabrik<br />

Oranienstraße 185<br />

10999 Berlin<br />

For business enquiries<br />

jonny@lolamag.de<br />

For editorial enquiries<br />

marc@lolamag.de<br />

Sub Editor<br />

Linda Toocaram<br />

For PR & event enquiries<br />

emma@lolamag.de<br />

Published by Magic Bullet Media<br />

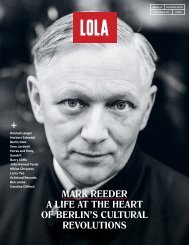

Cover photo by Robert Rieger<br />

Printed in Berlin by Oktoberdruck AG – oktoberdruck.de<br />

Summer 2017<br />

1

2 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Photo by Robert Rieger<br />

Contents<br />

04. berlin through the lens<br />

Notes of Berlin<br />

“What are people searching for?<br />

What are they complaining about?<br />

What have they lost? It’s an insight<br />

into everyday life in Berlin, but it’s<br />

not something that’s written in<br />

your typical tourist guide.”<br />

08. local hero<br />

Sara Neidorf<br />

“I think it’s really important to have<br />

people in your community who inspire<br />

you, and who you can look to<br />

as somebody who knows their shit.”<br />

12. Yony Leyser<br />

“When you make a documentary it’s<br />

like writing a memoir. You’re shaping<br />

a reality through a very big lens.”<br />

16. Pinball in Berlin<br />

“As the day wears on, cries of<br />

“Scheiße!” can be heard across<br />

the room.”<br />

20. cover story<br />

Moderat<br />

“We don’t yet know when we will<br />

continue with Moderat, and we<br />

also can’t say if. So this Berlin concert<br />

will be like the end of an era!”<br />

26. Jessica Lauren Elizabeth Taylor<br />

“The community really keeps me<br />

going: just when I feel like I’m<br />

ready to leave or move on, this<br />

incredible community is like ‘Wait,<br />

no, we’re here.’”<br />

30. Microdosing<br />

“There’s definitely something<br />

major happening right now. I think<br />

these drugs will play a key role in<br />

the future, in psychiatry and other<br />

fields of medicine.”<br />

34. Mohammad Abu Hajar<br />

“I won’t accept going back to Syria<br />

as a humiliated person. I would<br />

only go back as a free person.”<br />

38. 20 Years of Melt Festival<br />

“There was a couple climbing on<br />

the crane at the Gemini Stage, on<br />

the very top of it, like 30 metres<br />

high, fucking.”<br />

40. Käthe Kollwitz<br />

“In 1943 she evacuated Berlin,<br />

shortly before her apartment<br />

was destroyed in a bombing that<br />

claimed much of her life’s work.”<br />

42. dispatches<br />

The Battle of Mosul<br />

“Too much is going wrong in this<br />

war, and too many photos are<br />

showing that to the world.”<br />

44. the last word<br />

Julia Bosski<br />

“Call a friend, go for some champagne<br />

and I’m back in the game.”<br />

Summer 2017<br />

3

Berlin Through The Lens<br />

Notes of Berlin<br />

BERLIN THROUGH THE LENS<br />

EXPLORING OUR PEN<br />

AND PAPER CITY WITH<br />

NOTES OF BERLIN<br />

words by Marc Yates<br />

Whether fluttering in the breeze or streaked with running ink in the<br />

rain, Berlin’s handwritten posters, ads, announcements and notes are<br />

part of the fabric of the city – a sticky taped, pasted up, stapled staple<br />

of our urban landscape. They are everywhere. But why is it that such a<br />

lo-fi means of communication continues to thrive in the digital age, and<br />

what does it tell us about the people we share our city with?<br />

Joab Nist is in the seventh year of running Notes<br />

of Berlin, a website that seeks to answer these<br />

questions while archiving and paying homage to<br />

the expressions of frustration, anger, love, humour<br />

and desire left by Berliners on every available surface.<br />

What started as a blog has since become two books, a<br />

popular annual calendar, and Joab’s full-time job. We<br />

meet with Joab to talk about the motivation behind<br />

the project and the fascination with public proclamations<br />

that keeps it going.<br />

What was the inspiration behind Notes of Berlin?<br />

I was always taking photos, especially in places I’d<br />

never been before. Not wanting to take pictures of the<br />

typical tourist sites – I was curious about discovering<br />

the residential and industrial areas. That’s something<br />

I did when I came to Berlin as well. In the beginning<br />

I was very curious, as it was new. But the curiosity<br />

didn’t go away, so I often walked around and took<br />

pictures of anything that, for me, was typical of Berlin.<br />

The written notes all around the city were something<br />

I hadn’t seen anywhere else in that quantity. They<br />

became some sort of treasure for me. When you are<br />

new to Berlin, you want to discover how the people are<br />

here: what do they think about, what’s on their minds?<br />

It could’ve been that a note was very creative, very angry,<br />

very political, romantic, maybe lonely – everything<br />

that came to mind when I was thinking about Berlin.<br />

What are people searching for? What are they complaining<br />

about? What have they lost? It gives an insight into<br />

everyday life in Berlin, but it’s not something that’s<br />

written in your typical tourist guide. It’s completely<br />

unfiltered. It’s the truth, and to some extent you can<br />

identify with a situation that may have happened.<br />

So I tried to find as many notes as I could, but it’s not<br />

so much a matter of time as a matter of being at the<br />

right place at the right time. That’s when the idea came<br />

to document as many as possible, to really capture the<br />

character of the city, to style a project that everyone<br />

could contribute to by sending in the notes they see.<br />

What is it about the notes that people find so<br />

compelling? It’s definitely not only one thing. The<br />

main thing I think is that a lot of the topics that you<br />

4 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Notes of Berlin<br />

Berlin Through the Lens<br />

Top left: “Lost dog: on February<br />

28th around 15:30pm, our<br />

dog boarded the M13 tram at<br />

Schönhauser Allee without me.<br />

Who saw this happen and can<br />

help us find him? He responds<br />

to the name ‘Baader’, has a<br />

chip and a heart condition, and<br />

hobbles on the right hind leg.”<br />

Top middle: “CAREFUL. OLD<br />

MAN SPITS FROM BALCONY.”<br />

Bottom left: “PISS HERE ONE<br />

MORE TIME AND I’LL SHIT IN<br />

YOUR MOUTH!”<br />

Bottom right: “Elevator doesn’t<br />

work, you’ll have to walk, eh!!!”<br />

Previous page, right: “In my<br />

darkest drunken hour of the<br />

night on Friday, you carried<br />

me home up to the third floor<br />

– that was definitely no fun.<br />

For that, lovely French girl,<br />

THANK YOU!”<br />

find in the notes are things that every one of us<br />

faces each day. Your neighbour is having loud<br />

sex; your mail is not getting delivered; someone<br />

throws garbage in front of your house; your bike<br />

gets stolen; you have a political opinion you want<br />

to express; you saw someone in the U-Bahn that<br />

you want to see again; you’re searching for a flat.<br />

If you live in a city, you experience all of these<br />

things to some extent, so it’s very easy to identify<br />

with the people who write these notes because it’s<br />

someone just like you and me.<br />

Another reason people like to follow the notes is<br />

because they are from Berlin. It’s more interesting<br />

than it would be if they were from Frankfurt or Hamburg,<br />

for example. Also, if you were to go to Hamburg,<br />

Munich, Cologne or wherever, you wouldn’t<br />

find these kinds of notes. They’re not there.<br />

Why do you think this form of communication<br />

is so widely used in Berlin? It’s just normal<br />

for the people living in Berlin that you make<br />

use of this form of communication. It just fits<br />

somehow. I think it’s not surprising that people in<br />

Berlin like to express what they think. They started<br />

on the Berlin Wall, you have graffiti, street art,<br />

urban gardening, all movements where people are<br />

taking part in creating the cityscape.<br />

I did a test four or five years ago in Munich. I<br />

stuck some creative notes around the subway stations<br />

and I saw people taking them down, without<br />

reason, just because they thought they didn’t fit.<br />

But besides the cityscape, you need the people. You<br />

need a certain clash of cultures, of nationalities, to<br />

create the situations that result in the notes.<br />

Do you find common themes among the notes<br />

that you think are particularly ‘Berlin’ in<br />

nature? There are some notes that you can easily<br />

assign to some districts: things that children lose,<br />

or some really fucked up things that happen in<br />

Wedding, more international things that happen<br />

in Neukölln and Kreuzberg. But when it comes<br />

to the themes, there are main topics that you can<br />

identify in the notes: neighbours, sex, stealing,<br />

Summer 2017<br />

5

Berlin Through the Lens<br />

Notes of Berlin<br />

dirt, noise, love, the search for flats, bicycle theft,<br />

packages that don’t get delivered…<br />

These things are so relatable. Do you think you<br />

could use the notes to create a profile of the<br />

typical Berliner? [Laughs] I was actually planning<br />

to do a little story based on real notes and how a<br />

day or a week in Berlin unfolds. So, you wake up<br />

because your neighbour is being noisy, you find<br />

that your bike has been stolen, you lose your wallet<br />

on the way to the U-Bahn, where you see someone<br />

who you want to see again, you spend your day<br />

searching for a new apartment… it’s the everyday<br />

life of people living here.<br />

What you’re capturing is such a deeply personal<br />

view of the city, and what it really means to<br />

live here. You just can’t make it up. And even if<br />

this form of communication is beginning to disappear,<br />

people have sent in 18,000 or 19,000 notes<br />

over the last few years. It’s an archive that will<br />

never really go away.<br />

Do you write notes yourself? Yeah. I found my first<br />

apartment through writing a note. I wrote a note and<br />

stuck it around certain streets where I wanted to live,<br />

and two days later some artist called me and told me<br />

I could live in his apartment for the next year.<br />

Also, some years ago I met a girl in a club. We<br />

walked to the tram station together but I didn’t ask<br />

for her number; maybe I was too shy [laughs]. So<br />

I wrote a note because I wanted to see her again. I<br />

knew where she lived because she told me where<br />

her tram station was, so I stuck 20 or 30 notes<br />

around the station and she called the next day.<br />

You had an exhibition recently, a room in temporary<br />

art space THE HAUS - Berlin Art Bang.<br />

Tell us about that. Something I always wanted<br />

to do was to have a room completely covered with<br />

notes that I printed out. I covered the ceiling, the<br />

walls and the floor with the best of the last six<br />

years. I have done certain exhibitions but not such<br />

creative ones as this, and it’s a very nice feeling.<br />

I spent sometimes one or two hours in the room<br />

watching people – I don’t usually get to see my<br />

audience so it was a great motivation. It makes you<br />

happy to see that you are making people happy. I<br />

would like to continue more with the exhibition<br />

stuff, the material is there.<br />

Apart from potentially more exhibitions,<br />

what’s next for you? I’m planning to do another<br />

photo book, but it will be made with quality<br />

paper and design in mind. Of course it’s way more<br />

expensive to produce that kind of book, so it won’t<br />

be an amazing commercial project, it will address a<br />

different audience.<br />

Once you know about Notes of Berlin, it’s impossible<br />

not to notice them everywhere. Contribute your<br />

finds to the project at notesofberlin.com<br />

Top left: “Calling the cops<br />

because of loud music???? How<br />

pitiful!!! Move to Charlottenburg if<br />

you want quiet!!!!”<br />

Top right: “Doorbell is defective!<br />

Either call, yell, or go home!”<br />

Bottom left: “Optimist seeks<br />

2-room flat for themselves<br />

and their daughter, up to 400€<br />

all included.”<br />

Bottom middle: “To the two<br />

‘fucking-acrobats’ in the building.<br />

It would be fantastic if you would<br />

close the window during your<br />

nightly yodelling practice and not<br />

tyrannise the entire neighbourhood.<br />

It makes us sick that we’re<br />

constantly being ripped out of<br />

our sleep by your howling and all<br />

the residents have to close their<br />

windows, just because your ‘openair<br />

tournament’ fills the whole<br />

courtyard. Screwing is not an<br />

Olympic discipline and your nightly<br />

presentations won’t be greeted<br />

with thunderous applause.”<br />

6 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Berlinstagram<br />

Berlin Through the Lens<br />

Summer 2017<br />

7

Local Hero<br />

Sara Neidorf<br />

LOCAL HERO<br />

SARA NEIDORF<br />

EMPOWERING<br />

WOMEN IN MUSIC<br />

As a musician, drum teacher and film festival organiser,<br />

Philadelphia-born Sara Neidorf has been<br />

on a mission to improve Berlin’s cultural landscape<br />

for women and genderqueer individuals since she<br />

landed here in 2012.<br />

We meet in her drum studio, a black box tucked<br />

away behind a carpenter’s workshop on Sonnenallee.<br />

We’re a little early, and as she coaches her<br />

student through Black Sabbath’s ‘Iron Man’, we<br />

notice how quiet, poised, and watchful Sara is –<br />

the kind of teacher who cares about more than<br />

mere instruction. She’s a mentor.<br />

8<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Sara Neidorf<br />

Local Hero<br />

«<br />

MY ENTIRE<br />

STUDENT BASE<br />

IS FEMALE OR<br />

GENDERQUEER.<br />

THAT’S WHY I DO<br />

THE WORK I DO.<br />

»<br />

words by<br />

Maggie Devlin<br />

photos by<br />

Viktor Richardsson<br />

Iron Man<br />

The song took it’s name from<br />

vocalist Ozzy Osbourne’s comments<br />

upon first hearing the<br />

main riff, as he said it sounded<br />

“like a big iron bloke walking<br />

about.” It later earned a place<br />

on Rolling Stone’s list of the<br />

500 Greatest Songs of All Time,<br />

and VH1 named it the greatest<br />

heavy metal song ever.<br />

The lesson finishes with Sara’s student telling us<br />

we should check out her band’s first show. Her<br />

confidence warms the heart and is precisely<br />

why Sara is so important in a scene where women<br />

often struggle to get ahead.<br />

Was teaching drums part of the plan when you<br />

moved here? I’ve been teaching since I was 17. My<br />

school didn’t really have a music department; there<br />

was no drum set on campus. So I convinced the<br />

dean’s office to purchase one in exchange for me<br />

giving free drum lessons. Then I came here, and it’s<br />

really all I’ve done, steadily. Teaching drums is the<br />

job I know best and that I’ve done for the longest.<br />

What do you think your students get from<br />

learning drums? With my younger students, I can<br />

definitely tell that they love being loud. It seems<br />

to be really liberating for them. They get their<br />

earphones and they’re like, [mouths screaming,<br />

mimes drumming]. That’s usually always the first<br />

five or ten minutes, just letting them get that out of<br />

their system without too much structure. After that,<br />

I encourage them to start simple things, and we<br />

keep going with that for as long as it’s fun. I think<br />

they have a lot of fun having the freedom to make<br />

unstructured noise and just be kind of aggressive.<br />

And what do you get from teaching? I personally<br />

love the drums so much, so spending all day surrounded<br />

by them is a pleasure for me. I like knowing<br />

I can pass on that passion to someone else, because<br />

it’s such a satisfying way to express yourself; it’s<br />

non-verbal. We struggle with verbal communication<br />

all the time, so I think music is such a great escape<br />

from miscommunications and missteps. We’re all<br />

on the same page: we all just want to express something,<br />

to communicate with each other, and I think<br />

doing that on a musical level is really refreshing.<br />

So I hope I can pass that on; that ability to express<br />

yourself outside the verbal realm.<br />

What would you like to see change for women<br />

in Berlin’s music scene? Is the future on your<br />

mind? Of course, of course it’s on my mind. My<br />

entire student base is female or genderqueer. That’s<br />

why I do the work I do. I want there to be more<br />

female musicians, I always want it to be better. I<br />

found a couple of really important role models when<br />

I was learning the drums as a teenager. Having them<br />

around was essential to feeling motivated, encouraged<br />

and welcome to learn as a drummer. I think it’s<br />

really important to have people in your community<br />

who inspire you, and who you can look to as somebody<br />

who knows their shit. At least for me it was.<br />

You seem really invested in Berlin’s musical<br />

landscape. How did you come to be here? I was<br />

here as an exchange student for a semester and I<br />

really fell in love, not just with Berlin, but with so<br />

many different things about the city. I found some<br />

people I connected with in the music scene, but my<br />

main thing was the underground cinema culture.<br />

I encountered the Queer Film Club, which I now<br />

help to run. And there were all these awesome film<br />

festivals, I was really impressed with them; how they<br />

had such a rebellious and odd spirit. I was inspired<br />

by that, and now I’m running one!<br />

Yes! So, tell us about Final Girls Film Festival.<br />

It’s a festival dedicated to horror films made by<br />

women. We’re in our first year, but already on<br />

Summer 2017<br />

9

Local Hero<br />

our second festival, because when we<br />

opened up our call for submissions for the<br />

first we received over 400. For the second<br />

festival, we have XX, which is a horror anthology<br />

with four female directors; Karyn<br />

Kusama, Roxanne Benjamin, Jovanka<br />

Vuckovic and St. Vincent, which is pretty<br />

rad. We also have an art exhibition and a<br />

couple of talks. I’m going to give one with<br />

my mom about ‘horror hags’ – these huge<br />

Hollywood stars who fell from grace and in<br />

their older years couldn’t get any serious<br />

roles. They were just booked in B-horror<br />

movies, basically, and turned into a spectacle<br />

for being middle-aged – a horrific,<br />

ageing woman.<br />

You’re also in a band, Choral Hearse.<br />

Yes, my doom metal band. Half of our<br />

songs I wrote as a teenager. I came up<br />

with a full album of material that I had<br />

written the guitar, drums and some bass<br />

parts for, and searched high and low for<br />

awesome female musicians in Berlin. I<br />

didn’t even have the intention to start<br />

a band with it, but then this friend had<br />

told the singer, Liaam, that I had some<br />

music and she was like, “Oh cool! I’ll be<br />

in a metal band.” We started as an acoustic<br />

duo: acoustic folk metal – that was<br />

fun! Eventually we expanded and now<br />

we’re a full band.<br />

Sara Neidorf<br />

«<br />

I THINK MUSIC IS<br />

SUCH A GREAT<br />

ESCAPE FROM<br />

MISCOMMUNICATIONS<br />

AND MISSTEPS.<br />

»<br />

You’re a well-known face on the music<br />

scene, and visible as a champion of<br />

female musicianship… Wait until you see<br />

me play guitar with Choral Hearse. [Laughs]<br />

How much do your projects intersect<br />

with the queer and feminist scenes?<br />

The film festival more directly, you could<br />

say. The music, I mean, in terms of the<br />

content, not in any obvious way. But all<br />

four of us in Choral Hearse are queer.<br />

I don’t want to be a ‘female drummer’,<br />

just a drummer, but I’m okay with being<br />

a female drummer, I don’t get angry<br />

with being designated as such. It is, in<br />

many ways, also a shortcut for finding<br />

each other – if a band is playing I want<br />

to know if they have a female drummer,<br />

‘cause I’ll go and see them.<br />

It would be, of course, wonderful if<br />

every show that you went to had a female<br />

drummer in it. If it was three bands and<br />

definitely one had a female drummer,<br />

yeah, that would be ideal, but how many<br />

shows have you been to where all you see<br />

on stage is white men? Most of the shows<br />

I’ve ever been to.<br />

What’s been your high point in music<br />

to date? My favourite thing is always practising<br />

the music. For me that’s the high<br />

point. Shows are great, but I get the true<br />

high when I’m just focusing on the music<br />

in the practice room.<br />

What can we do to support female<br />

musicians in Berlin? Support your<br />

friends who are trying to earn their<br />

living with music. Keep them in mind<br />

for music jobs or creative jobs in<br />

general. Share their events on social<br />

media. Also, it’s really important to let<br />

them know you appreciate what they<br />

do. We all really thrive on validation.<br />

Buy their music. Buy their CDs. Go to<br />

their shows. Make them feel seen and<br />

acknowledged and appreciated for<br />

what they’re doing.<br />

Follow the Final Girls Berlin Film Festival<br />

at facebook.com/finalgirlsberlin and listen<br />

to Choral Hearse at soundcloud.com/<br />

choralhearse<br />

Horror Hags<br />

Notable horror hags include Joan Crawford and<br />

Bette Davis, whose performances in 1962’s What<br />

Ever Happened to Baby Jane? are lauded as the<br />

beginning of the sub-genre of horror known as<br />

psycho-biddy, or hagsploitation.<br />

10 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Our Summer Negroni<br />

by<br />

Summer 2017<br />

11

Queer and Now<br />

Yony Leyser<br />

TRANSGRESSION,<br />

DESIRE, REVOLUTION:<br />

DIRECTOR YONY LEYSER<br />

ON BREAKING RULES<br />

Director Yony Leyser is as curious<br />

as he is warm. A born interviewer,<br />

he poses as many questions as he’s<br />

asked, and delights in little idiosyncrasies<br />

on the Neukölln streets that<br />

he walks down each day: the grimy<br />

sex shop, the fishmonger, the tiny<br />

hut at the entrance to a car park<br />

on Karl-Marx-Straße. “I’ve always<br />

wanted to rent this as my office,”<br />

he laughs. “Wouldn’t that be great?”<br />

12 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Yony Leyser<br />

Queer and Now<br />

Perhaps it’s this fondness for the incongruous<br />

that contributes to the power of his work. In<br />

his films, transgression and desire act as catalysts<br />

for countercultural revolutions, be it through<br />

a vibrant portrait of Beat Generation icon William<br />

Burroughs in his 2010 documentary William S.<br />

Burroughs: A Man Within or explorations of identity<br />

and queer underground in 2015’s Desire Will Set You<br />

Free. Both films exhibit a profound interest in people<br />

upsetting the system, driven by passion, paradox, art<br />

and community. “When you make a documentary<br />

it’s like writing a memoir,” says Yony. “You’re shaping<br />

a reality through a very big lens. People think<br />

documentary is like a photograph of something,<br />

when in actuality it’s more like a painting.”<br />

Yony was born in DeKalb, Illinois and went on<br />

to study at California Institute of the Arts and The<br />

New School in New York. “Before I was making<br />

movies I was an anarchist; I was an activist,” he<br />

explains. “But being an activist was too didactic. I<br />

had too much humour and I figured art was a more<br />

effective and fun way to do it.” The art of filmmaking<br />

in particular allowed him to roll all his passions<br />

into one: “I was always interested in writing and<br />

journalism and documenting, photography,<br />

theatre, and I figured film kind of encapsulates<br />

everything. It’s such a powerful medium.”<br />

A Man Within happened almost by accident, as<br />

great works of art often do. After making an art piece<br />

at CalArts criticising the dean of students and illegally<br />

using her signature, Yony was given the option of<br />

either facing prosecution or taking a leave of absence.<br />

So, he moved to Lawrence, Kansas planning to make<br />

a documentary on counter-culture. Coincidentally,<br />

Lawrence was William Burroughs’ home for the final<br />

years of his life. Gradually, Yony made friends with<br />

Burroughs’ friends, and eventually the film evolved<br />

into a portrait of Burroughs himself.<br />

Burroughs was a fascinating subject: a gun-toting,<br />

cat-loving, queer junky who shot his wife<br />

in the head and made an unprecedented mark<br />

on literature. Making a film about such a largerthan-life<br />

icon was no small feat. However, Yony<br />

managed to successfully marry the enigmatic<br />

persona with the conflicted man behind it. Only<br />

21 at the time, his audacity, talent and persistence<br />

got him interviews with Burroughs’ lovers, friends<br />

and contemporaries from the fields of art, literature<br />

and music. “His friends wanted to talk about<br />

him,” says Yony. “It was this ripe subject.”<br />

Making the film allowed Yony to honour the man<br />

whose writing had had such a profound influence<br />

on both him and the queer community at large. “I<br />

liked that he was the first to break the rules,” he<br />

says. “I always felt like someone who didn’t fit into<br />

society and I just was kind of imagining someone<br />

who was this outcast, who was queer and didn’t fit<br />

in, and was rebellious and created his own realities,<br />

and did it at a time when no one had ever done it<br />

before. Genet too, all these kinds of people paved<br />

the way for the subcultures that I took part in.”<br />

The result is stunning. A Man Within weaves<br />

together footage and anecdotes of a long and<br />

astonishing life riddled with joy, lust, addiction,<br />

pain, tragedy and poetry. Grainy footage of Burroughs’<br />

face stares you down as his growly voice<br />

recites his own erotic and abject verses in the<br />

perfect cadence of a poet. The film splices together<br />

never-before-seen footage from Burroughs’ life<br />

with interviews with punks, poets and counter-cultural<br />

greats including John Waters, Patti Smith,<br />

words by<br />

Alison Rhoades<br />

photos by<br />

Robert Rieger<br />

DeKalb, Illinois<br />

The city was named after decorated<br />

German war hero Johann<br />

de Kalb, who died during the<br />

American Revolutionary War.<br />

Other notable people from<br />

DeKalb include model and<br />

actor Cindy Crawford, author<br />

Richard Powers, and the inventors<br />

of barbed wire.<br />

Summer 2017<br />

13

Queer and Now<br />

Yony Leyser<br />

« I’M SICK OF SEEING OR<br />

HEARING STORIES OF<br />

WHITE, HETEROSEXUAL<br />

COUPLES DOING BORING,<br />

MIDDLE-CLASS SHIT. »<br />

Iggy Pop, and Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. Icons of<br />

the Beat and punk movements − the artists, the<br />

outcasts, those who upset social norms – talk about<br />

their friend and hero with tender conviction, scraping<br />

together memories as if trying to sort out who<br />

indeed the ‘man within’ really was, once and for<br />

all. The point is probably that we’ll never know. But<br />

that’s the beauty of examining a life through film:<br />

you realise just how complex humans actually are,<br />

how riddled with contradictions.<br />

Yony’s next film, Desire Will Set You Free, is part feature<br />

film, part documentary, and full-on love letter<br />

to Berlin. At once a great departure from his previous<br />

film and a natural next step, it portrays the city in all<br />

its poor, sexy glory. The film follows American writer<br />

Ezra and Russian escort Sasha on a fast-paced ride<br />

through Berlin’s hedonistic queer underground.<br />

It is a study in dualities: Ezra (played by Yony<br />

himself) is an American of Palestinian and Israeli<br />

heritage, Sasha is a man discovering that he’s a<br />

woman, and their friend Cathrine is a bisexual<br />

radical obsessed with Nazi paraphernalia. It<br />

invokes the contradictions of Burroughs, and plays<br />

with Berlin’s divided past by depicting characters<br />

at war with themselves, who are two things, or<br />

everything all at once.<br />

Yony was eager to change gears and do something<br />

new, despite the success of his previous<br />

film. “The system tells you to do the same<br />

thing,” he says. But after years of working on a<br />

relatively straightforward documentary, Yony<br />

wanted to depict his life in Berlin in a more non-traditional<br />

way: “I really wanted to experiment and<br />

use my training as a documentary filmmaker to tell<br />

a true story and use non-actors, but do it in a fictional<br />

approach and not a documentary approach.<br />

And it was so fun! Shooting Desire was so much fun.<br />

I feel like in a way, it documents just as well as it<br />

would if it was a straightforward documentary.”<br />

There is a clear storyline, but Desire is also characterised<br />

by its non-linearity, with long and beautiful,<br />

poetic sequences of the characters simply relishing<br />

in the pleasures of having bodies, exploring, and<br />

improvising. Yony says that the film was indeed<br />

“hugely improvised.” He continues: “When it wasn’t<br />

100% improvised, the text was based on real events;<br />

like if it was about these two sex workers at this bar or<br />

whatever, then we would go to the bar the night before<br />

and hang out with those sex workers and then use that<br />

text the next day in the shooting.” The cast is also composed<br />

of “either real characters or a mix of real characters.<br />

There are only three actors in the film,” says Yony.<br />

“The rest are playing themselves.” In fact, the film was<br />

inspired by Yony’s encounter with a Russian man who<br />

came to Berlin to party before the Mesoamerican-predicted<br />

end of the world on December 21st 2012, and<br />

came out as a woman during her visit.<br />

Desire is like wandering into a dream where<br />

narratives don’t always make sense, choices are<br />

non-binary, and the landscape is governed, not by<br />

rationality or even morals, but by lust and invention.<br />

Yony cites Instagram as a visual inspiration for<br />

the film. It reads as such, swiping through colourful<br />

vignettes composed with seductive humour: Nina<br />

Hagen offering life advice from a trailer, trans-men<br />

and -women sharing their coming-out stories over<br />

mid-morning champagne in a sunlit squat. Late<br />

afternoons are spent naked with friends bathed in<br />

sun and glitter, exchanging philosophical musings<br />

and taking drugs. Night unveils the anachronous<br />

pleasures of Berlin’s dark underbelly, from Peaches<br />

performing in a plush breast-suit to leather daddies<br />

flexing their muscles for a cheering audience.<br />

“I actually thought it would be even more<br />

fractured,” Yony says. “And if I could do it again I<br />

would make it even more fractured. Just because I<br />

feel like this city is a dream and it’s about a dream<br />

and even in our daily lives we have ideas of what<br />

we want to do, like ‘I’m going to this interview and<br />

then I’m going grocery shopping or to a play’, and<br />

then little things happen in between, like you see<br />

someone on the street doing something weird or<br />

crazy. I think that’s also part of the Berlin atmosphere,<br />

at least for me: you’re going to a meeting<br />

and you walk through Görlitzer Park and you see<br />

people having sex in the bushes or whatever, and<br />

it’s like these moments of distraction.” He smiles:<br />

“That’s how life is; life doesn’t play out like it does<br />

in a Hollywood movie, you know?”<br />

Radical Gay Punk Zine<br />

J.D.s ran for eight provocative<br />

issues from 1985 to 1991, and<br />

is considered the catalyst that<br />

pushed the Queercore scene<br />

into existence. Founder Bruce<br />

LaBruce claims that the name<br />

initially stood for ‘juvenile delinquents’,<br />

but “also encompassed<br />

such youth cult icons as James<br />

Dean and J. D. Salinger.”<br />

Yony first came to Berlin in 2007 on a Fulbright<br />

scholarship. “I fell in love with it,” he says. “I was<br />

living in New York at the time and I was so stressed<br />

out and the quality of life here was so amazing. I<br />

14 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Yony Leyser<br />

Queer and Now<br />

remember my first weekend out, waking up<br />

in a queer squat and having breakfast with<br />

12 drag queens in the morning after some<br />

performance and I was just like, ‘I gotta<br />

figure out a way to live in this city.’ The<br />

subcultural landscape, especially the queer<br />

subcultural landscape, was really impressive<br />

to me. The use of public space, the idea<br />

of street culture and people of all backgrounds<br />

intersecting with each other on the<br />

street was very inspiring as an artist.”<br />

Does Desire have anything to say about<br />

Berlin? Yony pauses to think for a moment:<br />

“To me it did – to my version of Berlin.<br />

People can be very critical of that because<br />

there are a lot of versions of Berlin depending<br />

on who you are, and of course class<br />

and race and gender and cultural background<br />

and neighbourhood or whatever,<br />

they all play such big roles. Even in my<br />

building, for example, how differently all<br />

the neighbours live and what the city, the<br />

neighbourhood, or the building means to<br />

us is vastly different. So it’s hard to say that<br />

a film could represent the city, but what<br />

I thought was interesting was that Berlin<br />

had something very special that other<br />

cities didn’t have: this kind of psychedelic,<br />

Club Kid nightlife, and then this kind of<br />

multicultural mixing pot of expats and<br />

people who came to the city not for work<br />

but for a cultural escape, or to live out their<br />

fantasies. I wanted to depict the world as<br />

parallel to the 1920s in Berlin − Christopher<br />

Isherwood’s ‘20s or early ‘30s.”<br />

In both A Man Within and Desire, the importance<br />

of community in queer culture is a<br />

noteable throughline. “Well, for a lot of queer<br />

people, a lot of ostracised people, the idea of<br />

a queer community is like creating your own<br />

family because a lot of people’s families don’t<br />

accept them and aren’t there for them,” explains<br />

Yony. “So they can’t relate to them and<br />

they can’t relate to a lot of society, so they say<br />

‘let’s create our own tribal family’. It’s a very<br />

central theme in my new film, too.”<br />

Yony’s upcoming film, Queercore: How to<br />

Punk a Revolution, premieres at the Sheffield<br />

Documentary Festival this summer.<br />

“It’s a documentary about the movement<br />

that Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones started<br />

in the late ‘80s, a gay punk movement, and<br />

it started as a farce,” says Yony. “They got<br />

a bunch of straight punks drunk and took<br />

pictures of them and wrote these stories of<br />

all these bands in Toronto being gay in this<br />

radical gay punk zine, and people believed<br />

it. It was before the internet so people<br />

couldn’t really fact check, so the zine<br />

spread and all these bands started. It led to<br />

bands like Gossip, Peaches, The Knife; all<br />

these guys kind of got their start from this<br />

Queercore thread from the ‘90s.”<br />

The German director Rainer Werner<br />

Fassbinder once said: “Every decent director<br />

has only one subject, and finally only<br />

makes the same film over and over again.”<br />

Yony bristles a bit when asked what this<br />

subject might be for him, or indeed what<br />

drives him as an artist. He turns the question<br />

back around: “What do you see?” For<br />

a director driven by a quest to discover the<br />

hidden desires, passions and pleasures<br />

that spark creative communities and even<br />

radical progress, this is a fitting retort. But<br />

upon reflection, he offers this: “I like to tell<br />

stories from marginalised communities.<br />

I’m sick of seeing or hearing stories of<br />

white, heterosexual couples doing boring,<br />

middle-class shit, and that’s what 90%<br />

of films are. I think it’s quite boring and I<br />

think there are very interesting marginalised<br />

cultures that are doing interesting<br />

things that can also play out in film, and<br />

should have a place there, too.” Challenging<br />

norms and subverting the language of<br />

cinema to be more inclusive and more daring<br />

is a noble goal, and Yony is definitely<br />

up to the challenge. After all, as Burroughs<br />

himself once wrote: “Artists, to my mind,<br />

are the real architects of change, not<br />

the political legislators who implement<br />

change after the fact.”<br />

You can find William S. Burroughs: A Man<br />

Within and Desire Will Set You Free on<br />

streaming platforms now. Queercore: How to<br />

Punk a Revolution will hit cinemas in Berlin<br />

later this year.<br />

Summer 2017<br />

15

Game On<br />

Pinball<br />

A NICHE PASTIME MAKES A<br />

TRIUMPHANT RETURN AT THE<br />

GERMAN PINBALL OPEN<br />

The back corners of arcades, basements, and bars across the globe are home<br />

to hundreds of thousands of pinball machines. Some lay forlorn as their intricate<br />

web of parts give out, one by one. Others flourish in the care of tender<br />

hands and function as though they have just come off the assembly line.<br />

With the same appreciation as a vinyl collector or analogue photographer,<br />

pinball players adore these kinetic wonders of human innovation. Pinball is<br />

not a game of chance from a bygone era; it’s a combination of art and skill, at<br />

once repetitive and full of infinite variations.<br />

16 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Pinball<br />

Game On<br />

After decades of use, every machine plays<br />

differently. Repairs have been made,<br />

pieces modified to fit into place; some<br />

parts simply cannot be fixed. Each table is a<br />

Sisyphean puzzle, with players endlessly competing<br />

against their own highest score. And<br />

like life itself, no matter how good your game<br />

is, the ball always drains in the end.<br />

Despite achieving popularity as an American<br />

phenomenon, the general consensus is that pinball<br />

was invented in western Europe during the end<br />

of the 18th century as a spring-loaded variant of<br />

the French game, Bagatelle. They called it Billard<br />

Japonais – Japanese Billiards. As it had nothing<br />

to do with Japan, the game’s title was a misnomer.<br />

In an ironic twist, however, the same game also<br />

evolved into the Pachinko machine, Japan’s most<br />

widespread and beloved form of gambling.<br />

1940: New York City. Pinball machines were<br />

a largely mob-controlled business, and the<br />

press-hungry, bullish Mayor Fiorello La Guardia<br />

was sick of them. In an effort to combat what he<br />

saw as “mechanical pick-pockets,” La Guardia<br />

conducted prohibition-style raids on arcades and<br />

bars across the city. The ‘gambling machines’, as<br />

he saw them, were rounded up and smashed with<br />

sledgehammers, then dumped into the rivers. Major<br />

cities across the US followed suit, and in many<br />

places pinball became a criminal activity. Yet,<br />

despite its struggle, pinball lived on. Major companies<br />

continued to produce tables and distribute<br />

them to regions where the game had not been<br />

banned. In places like New York, pinball machines<br />

were imported on the sly, sitting in the back rooms<br />

of seedy porn shops and gambling dens.<br />

That was true until May 1976, when a young<br />

pinball fanatic named Roger Sharpe was brought to<br />

a Manhattan courtroom to play in front of the New<br />

York City Council. He was a good player, even rumoured<br />

to be the best. A writer for GQ and The New<br />

York Times, Sharpe gave an eloquent and logical<br />

explanation to the City Council about how pinball<br />

had evolved into a game of skill. To prove this he<br />

began to play ‘Eldorado’, one of two tables brought<br />

to court that day. The Council, keen to see a<br />

demonstration of such skill, requested that Sharpe<br />

play on the table that had been brought along as a<br />

backup. He was much less familiar with the second<br />

table, ‘Bank Shot’, having trained for his day in<br />

court on ‘Eldorado’. However, he stepped up to the<br />

second table and announced that the ball would<br />

pass through the middle lane of the playing field.<br />

Sharpe pulled back the metal plunger, launched<br />

the ball into play and sent it through the desired<br />

lane. He had called his shot, and the Council formally<br />

recognised pinball as a game of skill. Today,<br />

Sharpe looks like a typical dad. His formerly wild<br />

mustache has been trimmed, he’s neatly dressed,<br />

and wears glasses. At pinball conventions, however,<br />

he’s a living legend – known as the man whose<br />

bold demonstration of skill saved pinball.<br />

Following the City Council’s ruling, the<br />

machines became legal, and across the country<br />

pinball experienced a renaissance. At this<br />

point, pinball’s history starts to get pretty nerdy.<br />

Machines changed from electro-mechanical to<br />

solid-state, dot-matrixes were introduced, etc. To<br />

sum up: it was the 1980s. America’s arcades were<br />

packed. Capitalism and haircuts were out of control,<br />

and kids had coins to burn. Video games were<br />

already starting to encroach on the pinball market,<br />

which only fuelled the fire for pinball designers,<br />

who were trying to keep the game (and their jobs)<br />

alive. During the mid-1990s – like poets on their<br />

deathbeds racing to finish their magnum opuses<br />

– major pinball companies such as Williams and<br />

Bally produced the most technologically advanced<br />

and entertaining pinball machines ever made, but<br />

neither ‘Addams Family’ nor ‘Twilight Zone’ could<br />

stop the bubble from bursting. All of the companies,<br />

with one exception, eventually shut down or<br />

used their factories to produce a much more profitable<br />

coin-operated contraption: the slot machine.<br />

But pinball didn’t just lay down and die.<br />

Instead, it was martyred, and from the ashes of a<br />

once-thriving industry rose a new form of competitive<br />

play. Obsessive fans and barflies began<br />

putting their skills to the test as an official global<br />

ranking system, the International Flipper Pinball<br />

Association, emerged. Today, whether for amusement<br />

or for glory, players flock to pinball competitions<br />

all over the world. This brings us to Potsdam<br />

in 2017 for the 20th German Pinball Open.<br />

Pinball by nature requires a stretch of the<br />

imagination. In ‘White Water’, the ball represents<br />

rafters heading through turbulent rapids<br />

as it descends a bumpy ramp. In ‘Banzai Run’,<br />

the player is a dirt biker ascending a treach-<br />

words by<br />

Ryan Rosell<br />

photos by<br />

Soheil Moradianboroujeni<br />

Pachinko<br />

Gambling for cash is illegal in Japan<br />

so Pachinko players win steel balls,<br />

which can be exchanged for prizes or<br />

tokens. Pachinko balls are engraved<br />

with elaborate identifiable patterns<br />

specific to the premises they belong<br />

to, and this has led some fans to<br />

start collecting the different designs.<br />

Summer 2017<br />

17

Game On<br />

«<br />

CRIES OF “OOH”<br />

RIPPLE THROUGH THE<br />

GROUP AFTER EACH<br />

CLOSE CALL, AND<br />

PEOPLE BREAK INTO<br />

APPLAUSE BREAKS OUT<br />

AFTER PARTICULARLY<br />

NICE SHOTS.<br />

»<br />

erous mountain trail. Many of the games<br />

are wonderfully kitsch; they revel in their<br />

artificiality. So it makes perfect sense that<br />

this year’s German Pinball Open would take<br />

place in the Babelsberg Film Park, just down<br />

the road from the tryhard Quentin-Tarantino-Straße,<br />

in a building next to a giant<br />

mountain fabricated for a film set.<br />

Inside Metropolis Halle, lined up backto-back<br />

in neat rows, stand more than 160<br />

pinball tables. Their dates of manufacture<br />

span half a century, with the newest tables<br />

not even available to purchase yet. Some of<br />

the best machines in the hall come from that<br />

golden period, before neon-clad kids started<br />

begging their parents for Super Nintendos<br />

instead of arcade money. Many of those tables<br />

were produced in runs of less than 2000.<br />

Playing a game on one of these machines is<br />

like finding a piece of treasure.<br />

For the the crowd on opening day, however,<br />

it’s business as usual. Vendors selling replacement<br />

machine parts set up shop and begin jovially<br />

cutting deals with returning customers. Rivals<br />

vying for the same position on the podium<br />

taunt one another. Fanatics inspect the tables,<br />

arguing over the advantages and disadvantages<br />

of replacing bulbs with LEDs. There are punks<br />

Pinball<br />

with mohawks and pinball patches sewn into<br />

their jackets, nostalgic grandfathers who stick<br />

to the slow-paced machines of the ‘70s, and<br />

old friends who play sitting on bar stools they<br />

brought from home. Some of the serious players<br />

are already here, with fingerless gloves and<br />

headphones blasting EDM; they have the same<br />

tense, sobre manner as professional poker players,<br />

seemingly taking no enjoyment from the<br />

game. This day is mostly for freeplay, and many<br />

of the serious players stay at home, saving their<br />

strength for the serious competition.<br />

To say the crowd is diverse would be<br />

misleading, but it is certainly a diverse group<br />

of middle-aged white men. In their heyday,<br />

pinball machines traditionally catered to a<br />

male audience, and the back glass of many<br />

machines sports the likeness of a voluptuous,<br />

scantily-clad woman. This is a sad,<br />

sexist truth about the game, but it has begun<br />

to change in recent years. As the day rolls<br />

on, a small but noticeable percentage of pinball-playing<br />

women turn up, turning more<br />

heads than even the highest scores.<br />

Without any major competition on the<br />

first day, it seems the pinballers are in for<br />

nine or ten straight hours of uninterrupted<br />

pinball. That’s until the German Pinball<br />

Association guest of honour strolls into the<br />

hall: Gary Stern. In 1999, the already-merged<br />

Data East/Sega Pinball was about to go under,<br />

as so many American pinball manufacturers<br />

already had. In a courageous move as president<br />

of the company, Stern bought the assets,<br />

rallied an A-Team of unemployed pinball<br />

designers and founded Stern Pinball, Inc. The<br />

tables they produced may not always have<br />

been the greatest, but with keen marketing<br />

techniques and a steely resolve, Stern weathered<br />

the roughest years in pinball history<br />

as the owner of the last surviving company,<br />

which manufactures new tables to this day.<br />

EXTRA CREDIT:<br />

OUR PICK OF BERLIN’S<br />

HIGH-SCORING<br />

PINBALL SPOTS<br />

Logo Cafe<br />

Blücherstraße 61<br />

This Kneipe is open 24 hours a day,<br />

so you can scratch that pinball itch<br />

whenever it comes. They’ve got the<br />

new ‘Ghostbusters’ table and cheap<br />

drinks, but no matter how rowdy things<br />

might get, a player’s concentration is<br />

respected above all else.<br />

Ron Telesky Canadian Pizza<br />

Dieffenbachstraße 62<br />

This place gets it. Tasty pizza, good<br />

music, and ‘Medieval Madness’. Go<br />

have a slice and a ball on one of the<br />

best tables ever made.<br />

East Side Bowling<br />

Koppenstraße 8<br />

This place is bar-sports heaven. In<br />

addition to bowling they have ping<br />

pong, poker tables, pool, arcade<br />

games, and five pinball tables. It’s<br />

the only place inside the Ring where<br />

you can find more than two or three<br />

tables in one spot.<br />

Flipperhalle Berlin<br />

Kleinmachnower Weg 1<br />

This place is a game changer. It’s only<br />

open from 13:00 to 20:00 on Fridays<br />

and it’s in Zehlendorf, but the trip is so<br />

worth it. It’s €5 entry, and once you’re<br />

in you can play for free on all of their<br />

fifty tables. Plus, beers are €1. That’s a<br />

crazy deal. This is the cheapest way to<br />

fall in love with the game.<br />

18 <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Pinball<br />

Bird’s-eye View<br />

On the second day of the tournament, competitive play<br />

begins. A separate section of the hall is opened and competitors<br />

are assigned to tables in groups of four. While a massive<br />

amount of skill is required to become a pinball champion,<br />

there is also an element of luck. Some people are assigned to<br />

a table they know intimately, others step up to a table cold.<br />

As the day wears on, cries of “Scheiße!” can be heard across<br />

the room. Dreams are crushed, and competitors are slowly<br />

whittled down in number until only four remain.<br />

The showdown between the final four takes place on the<br />

third day. A surprise selection of three tables is presented,<br />

and the winner is chosen based on the culmination of their<br />

scores on all three machines. This year’s selection includes<br />

the Stern hit ‘Ghostbusters’, a table that has widely instilled<br />

faith in the pinball community by proving that new machines<br />

can be as good as the classics. The next is ‘Medieval Madness’<br />

from the 1990s, regarded as one of the greatest tables ever<br />

made. The last to enter the championship is ‘Domino’s Pizza’.<br />

This table, like most fast food, is pretty disappointing.<br />

The first of the finalists is Stefan Harold. He’s the oldest<br />

of the group but incredibly fast. He has the footwork of a<br />

featherweight boxer and his shoes dart back and forth under<br />

the table as he plays. Up next is young Roland Schwartz,<br />

hailing from Austria. He keeps a Swedish Pinball Championship<br />

hand towel tucked in his back pocket, which he uses<br />

to methodically wipe down the table and his hands before<br />

every ball. Next comes Martin Hotze, who won the German<br />

Open in 2015 and is a favourite with the crowd. Last is Armin<br />

Kress. He’s young and in decent shape, and when his ball<br />

inevitably drains, Armin is the only player not to become<br />

visibly upset. He just smiles modestly, steps back from the<br />

table, and waits for his next turn. A crowd of around 30 gathers<br />

around the finalists as they progress from table to table.<br />

Cries of “ooh” ripple through the group after each close call,<br />

and applause breaks out after particularly nice shots. None<br />

of the players do too well on the ‘Domino’s Pizza’ table.<br />

In the end, age and experience beat youthful enthusiasm,<br />

as the final game is between Harold and Hotze. The<br />

match comes down to the very last ball, but Hotze needs<br />

only a few flips to restate his position as German champion.<br />

Trophies are disseminated, awkward handshakes are<br />

exchanged and the crowd dissipates. The machines are<br />

carefully packed away by their owners and prepared for<br />

long journeys home. The crowd leaves the hall, many of<br />

them having played pinball for three consecutive days. The<br />

sun is bright, but it’s not flashing ‘EXTRA BALL’, so no one<br />

pays it much attention.<br />

Reading about pinball is not nearly as fun as playing it.<br />

Gather your spare change and check out our picks of the top<br />

spots in Berlin for a beer ‘n’ ball.<br />

KEVIN MORBY<br />

02.07.17, Quasimodo<br />

OF MONTREAL<br />

20.07.17, Festsaal Kreuzberg<br />

BEACH FOSSILS<br />

06.09.17, Musik & Frieden<br />

CHASTITY BELT<br />

17.09.17, Berghain Kantine<br />

CHAD VANGAALEN<br />

22.10.17, Berghain Kantine<br />

MOUNT EERIE<br />

05.11.17, Silent Green<br />

PEAKING LIGHTS<br />

12.07.17, Berghain Kantine<br />

ULRIKA SPACEK / THE MEN<br />

03.08.17, Berghain Kantine<br />

NADIA REID / MOLLY BURCH<br />

13.09.17, Berghain Kantine<br />

WAXAHATCHEE<br />

28.09.17, Musik & Frieden<br />

PRIESTS<br />

26.10.17, Urban Spree<br />

MAC DEMARCO<br />

08.11.17, Astra<br />

Summer 2017<br />

TICKETS & INFO: PUSCHEN.NET<br />

Spring 2017<br />

19

Cover Story<br />

MODERAT<br />

20<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> <strong>Four</strong>

Moderat<br />

Cover Story<br />

words by<br />

Gesine Kühne<br />

photos by<br />

Robert Rieger<br />

This summer, Berlin loses one of its most iconic<br />

acts to an undetermined hiatus. As Moderat<br />

begins what could be their final festival tour,<br />

we join them and talk transitions: past to present,<br />

and urban sprawls to garden walls.<br />

Moderat: the chimeric brainchild of techno<br />

giants Modeselektor and Apparat. Although<br />

their name means ‘moderate’ in German,<br />

their sound is anything but: sombre and sophisticated, exciting<br />

and often painfully lush. Moderat is a play on words,<br />

on genre, on sound and vision, and on what it means to be<br />

a live band. By definition a supergroup, the Berlin-based<br />

producers wear their status as ambassadors of the city<br />

with a casual air. They smile and cajole off stage, and let<br />

their music do the serious talking. Like many of Berlin’s<br />

closely-cherished heroes, they are of the city but not from<br />

it, hailing from small-town Germany and finding their<br />

futures in the grimy basement parties of the late ‘90s.<br />

Gernot Bronsert and Sebastian Szary’s Modeselektor is<br />

all punch, sex, grit and grime. A cross-section of ‘90s boom<br />

bap, stuttering vocal samples and bass drops that can feel<br />

like G-force training, as euphoric synths wrench the listener<br />

in all directions. It’s a union of blissful paradox – where<br />

Modeselektor thumps, Apparat whispers. Sascha Ring’s<br />

soulful dream-pop delights the ear with vocals that walk the<br />

line between the acrobatic and the strained, on a tapestry<br />

of nimble beats. Apparat skirts the radio mainstream but<br />

always manages to keep things off-centre, cementing his<br />

place as one of music’s countercultural superstars.<br />

Moderat lives an amphibious existence between both<br />

sounds: all the sensitivity and intricacy of Apparat, delivered<br />

with the take-no-prisoners moxie of Modeselektor. It’s<br />

a cocktail that wins hearts across the globe, and last year<br />

sold out Berlin’s massive Velodrom in a matter of minutes.<br />

Make no mistake: this band is loved in this town, a fact<br />

that makes this a painful year for fans. On September 2nd,<br />

Moderat will take to the stage at Wuhlheide where they’ll<br />

say an indefinite Auf wiedersehen. Until then, they’ll court<br />

the summer festivals, filling parks and melting heads with<br />

their visually stunning live set.<br />

We join them on the road to Reims in the heart of provincial<br />

France, where they will headline La Magnifique Society.<br />

It’s a brief foray: a weekend getaway with a 14-hour drive<br />

each way. It’s a lot of distance to cover for a one-hour set,<br />

but it’s the kick-off for festival season, and with a further 28<br />

shows to go, Moderat have more experience and grit than<br />

to quiver at overnight bus journeys, sleeping to the ambient<br />

hum of an engine a metre or so beneath their pillows.<br />

What is life on the road for Moderat? Backpacks with fresh<br />

underwear, packets of cigarettes and pressed baguettes from<br />

a sandwich toaster say ‘student digs’ rather than ‘club circuit<br />

celebrities’. Laughing, Szary insists that the toaster is one<br />

of the bus’s most valuable possessions: “A sandwich gets<br />

about 300% better when you grill it in a sandwich maker!”<br />

Compared to the band’s early days, he has a point – a sandwich<br />

toaster is a step up. “In the very beginning, we drove<br />

ourselves and shared a hotel room,” says Sascha.<br />

The Moderat project began in 2002 – the trio writing<br />

their own software so they could jam together, since<br />

what they needed wasn’t available off-the-shelf. They<br />

produced their first EP the following year. Auf Kosten der<br />

Gesundheit (At the Cost of Health) emerged to a flood of<br />

positive reviews, but the title and subsequent six-year<br />

hiatus hinted at a trying time behind studio doors. Nevertheless,<br />

in 2009, Moderat released their first full-length<br />

record: a self-titled opus of post-minimal, club-ready<br />

hits. Trampolining off the success of the first EP, Modeselektor’s<br />

Hello Mom and Happy Birthday!, as well as Apparat’s<br />

collaborative LP, Orchestra of Bubbles with Ellen<br />

Allien, Moderat was an unquestionable success.<br />

Despite their decade-long success, Gernot, Szary and<br />

Sascha have managed to remain grounded, avoiding the<br />

tropes of inflated egos with characteristic nonchalance. They<br />

still leave their hotel rooms to explore the surroundings of<br />

their latest gig, be it a city or somewhere more remote.<br />

“I mean, I grew up in a village, kind of, so I always have<br />

a need for green,” Sascha says. “Previously, I satisfied that<br />

desire by motorcycling into the woods, for example. Now I’ve<br />

found something that fits my age better. I drive to my piece of<br />

land, to my garden.” All three members have bought land just<br />

outside Berlin where they’ve each built houses – Sascha’s,<br />

next to a pond; Gernot’s, near the open countryside.<br />

“I realised that my job is done all over the world, but<br />

99.9% of everything happens in huge cities, so I don’t<br />

need to live in one any more,” Gernot says. “Back in the<br />

day, we destructively exploited our bodies,” he adds,<br />

explaining some of the reasons why the trio have turned<br />

away from urban living. “We only worked at night, then<br />

when we were done around five or six in the morning,<br />

we’d have another kebab and a beer and go to bed. We’d<br />

get up around two or three in the afternoon. We wasted<br />

so much time this way, but now we’re trying to optimise<br />

our lives. The environment we’re in and what’s in front of<br />

our door plays an important role; for example, no drunk<br />

tourists having the summer of their lives in Berlin.”<br />

Gernot continues, “That’s why the photos for <strong>LOLA</strong> were<br />

shot where we feel comfortable; where no one lives, where<br />

we don’t have to talk, and where no one recognises us. It<br />

happens a lot in the city: we go for a coffee, and all of a<br />

sudden we get a coffee for free because someone else offers<br />

to pay. That’s not bad, of course, but on the other hand you<br />

feel watched the whole time. Where we live now, north of<br />

Berlin, there is a little organic supermarket and they don’t<br />

care at all who shops there. They leave you alone,” he says,<br />

then laughs. “Unless you touch the vegetables.”<br />

As much as Gernot, Szary and Sascha love their newfound<br />

sanctuaries with their families, they equally love<br />

being on tour. “It is Tourlaub,” or ‘tour holiday’, Gernot<br />

says, smiling. “That’s the term our wives came up with.<br />

They don’t see touring as work.” But Sascha interjects,<br />

clarifying: “We wouldn’t call it Tourlaub, I mean, we are<br />

talking about sometimes playing every day for three<br />

weeks in a row. That really wears you out.” However,<br />

even on the road they manage to find a routine: “We have<br />

learned to live with a certain rhythm,” says Sascha. “During<br />

the day we wind down, and we still get very euphoric<br />

about our job on stage. It still gives us a huge kick.”<br />

Summer 2017<br />

21

Cover Story<br />

Moderat<br />

“We are touring professionals,” adds Gernot. “We<br />

toured as Modeselektor and Apparat before and during<br />

Moderat, and we know all forms of touring: as a band,<br />

as DJs with USB sticks, on buses, trains, planes, jets<br />

and boats. We haven’t had a helicopter yet,” he laughs.<br />

“When we get home the mode switches instantly<br />

because our kids take over, and they aren’t interested<br />

in what happened at Fabric, for example. Switching<br />

modes quickly is actually quite nice.”<br />

Szary agrees: “When I get home the first thing I do is<br />

I make myself some coffee. Then I go outside, drink it,<br />

and smoke a cigarette. Then I say, ‘Kids, come over, sit<br />

down on my lap, because Papi would like to explain to<br />

you what he has experienced.’ And after that, it is back<br />

to normal: clearing out the dishwasher…”<br />

In addition to giving them plenty to tell their children<br />

about when they return home, Tourlaub allows<br />

them to escape the routines of work, the record label,<br />

studio and family time, to travel with friends. And<br />

like friends, they listen carefully when any of the crew<br />

members have personal matters to talk about. “We are<br />

dependent on the crew,” Gernot explains. “They have<br />

to give 110% so we can deliver 120%. Trust and being<br />

nice to each other is essential.”<br />

“There’s no one in our crew who is just a worker,”<br />

Sascha adds. “They are all people we have known for<br />

ages. Most of them are part of the crew for exactly<br />

that reason. We grew together. We rarely have changes<br />

within the crew, and that’s important.”<br />

From the production manager to the technicians,<br />

the crew work with the kind of intimacy that comes<br />

from years of knowing each other. And Moderat<br />

is the fulcrum, the three characters creating the<br />

kind of balance needed to get through such punishing<br />

tour schedules. Sascha is the contemplative<br />

maverick who maintains the overview of production<br />

plans and costs. Szary pursues new interests and<br />

broadens his knowledge over coffee and cigarettes.<br />

His interest in foreign climes has made him the socalled<br />

travel minister, checking routes and researching<br />

hotels for the band. Then there’s Gernot, the<br />

cheeky, bright-eyed joker, who listens carefully and<br />

is able to parse out solutions to whichever obstacles<br />

present themselves. His demeanour and outgoing<br />

nature make him the perfect candidate for handling<br />

press and communication.<br />

Maintaining a jovial spirit isn’t always easy. Back<br />

on the bus, the clock reads half-past-midnight, and<br />