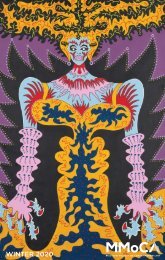

Kambui Olujimi: Zulu Time exhibition catalog

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

In fact, there is a great deal of visual poetry in <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s<br />

work—tiny catharses, moments of retinal splendor. His chandelier<br />

installation, titled Fathom (2017), is likewise transformative and<br />

disruptive. Typically identified with (white) privilege and wealth,<br />

chandeliers normally hang high overheard. In <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s sculpture, six<br />

ornate and opulent working chandeliers have been jarringly dislocated<br />

from their usual position and context. Now on the floor, they retain<br />

a residual elegance but also look ungainly and precarious. They are<br />

much closer now, not remote and magisterial, but right here, next<br />

to us, intimate chandeliers suggesting human bodies with slightly<br />

sagging postures. On the floor, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s chandeliers function not just<br />

as sources of light but also as fragile sources of power. The chandeliers<br />

rest like figures on a structure that refers to the improvised crafts<br />

used by refugees as they make dangerous ocean voyages. Fathom thus<br />

addresses a political and moral crisis. At a time when millions of<br />

vulnerable refugees are desperately seeking some measure of solace<br />

and safety, virulent hostility to immigrants is a rising force in many<br />

countries, including the United States.<br />

Importantly, despite their completely altered conditions,<br />

these chandeliers continue to function as they normally would; they<br />

continue to illuminate the room, or at least parts of it. This helps<br />

explain why <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s art is so distinctive, especially when it comes to<br />

his use of found objects and images. His objects—be they a chandelier,<br />

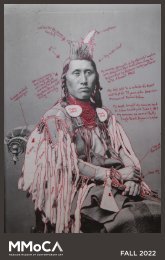

handcuffs, earrings, necklace, or photograph—retain a residual<br />

familiarity that points to their original function, while simultaneously<br />

existing as completely transformed. <strong>Olujimi</strong> leaves it for the viewer<br />

to move between these two contexts, the one familiar and at times<br />

mundane, and the other eccentric, destabilizing, misbehaving, and<br />

invigorating.<br />

Here it is worth recalling the great Russian literary critic and<br />

philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975), and his idea of the carnival,<br />

which he applied to literature (especially to Dostoevsky’s novels),<br />

but which can also be fruitfully applied to certain kinds of visual<br />

art, including <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s. 1 For Bakhtin, the “carnivalized moment” or<br />

“carnivalized situation” (or, in this context, the carnivalized object) are<br />

1. All quotes from and references to Mikhail<br />

Bakhtin are from his Problems of Dostoevsky’s<br />

Poetics, trans. Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis:<br />

University of Minnesota Press, 1984),<br />

122–124.<br />

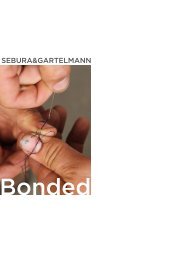

Facing, 42–43:<br />

Fathom<br />

40