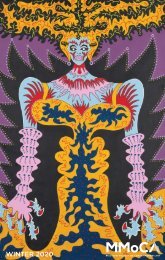

Kambui Olujimi: Zulu Time exhibition catalog

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

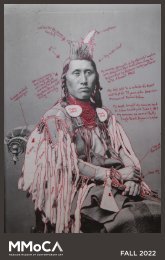

y conquest cultures and reflects Western visions of the African continent.<br />

Modernity’s aesthetic wing, shorthanded as modernism, relies upon traditions<br />

and practices that have notoriously fixed the nonwhite body within<br />

temporal stasis, if not regression, through representational traps that tarry<br />

between hypervisible and invisible, undesirable and lasciviously sexual.<br />

Modernism tends to maintain the temporal logics of modernity, which lock<br />

the Black body into a temporal logic of regression— the stereotype of the<br />

savage left behind by the West, and therefore stuck in History and therefore<br />

lagging behind in narrative progression. 4<br />

In light of this, <strong>Olujimi</strong> flips the script. He uses <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> as a<br />

point of departure, considering the ways that Blackness itself might always<br />

be imbedded in modernity’s logics of time and, by extension, structures<br />

of power. In other words, <strong>Olujimi</strong> suggests that “<strong>Zulu</strong>” being the name<br />

for a universal system of timekeeping is no coincidence. Because the word<br />

connotes a people whose anticolonial history has been oft-cited in Black<br />

freedom struggles across the world, “<strong>Zulu</strong>” connects Blackness to the field<br />

of temporal play. <strong>Olujimi</strong> calls attention to these vestiges in the structuring<br />

of everyday contemporary life, and, by extension, illuminates modernism’s<br />

role in the consolidation of white supremacy today. His is an anachronistic<br />

4. For more on the relationship between temporality,<br />

colonialism, and empire as it unevenly<br />

impacted African diasporic subjects, see: Anne<br />

McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and<br />

Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (New York:<br />

Routledge, 1995); Keya Ganguly, “Temporality<br />

and postcolonial critique,” in The Cambridge<br />

Companion to Postcolonial Literary Studies, ed.<br />

Neil Lazarus (New York: Cambridge University<br />

Press, 2004),162–182; Simon Gikandi, “Globalization<br />

and the Claims of Postcoloniality,” South<br />

Atlantic Quarterly 100, no. 3 (2001): 627–658;<br />

Barbara Fuchs and David J. Baker, “The Postcolonial<br />

Past,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly<br />

65, no. 3 (2004): 329–340.<br />

Black-aesthetic practice that takes time out of sync, and settles in the impasse<br />

of irreconcilable liminality. In this visual formulation, time becomes<br />

a mechanism through which we understand power through sight—what we<br />

see is not only what we get, but also what was given to us.<br />

To mobilize this kind of sight through <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s works is to suspend<br />

oneself between explosion and implosion, and ultimately to practice<br />

modes of relationality gripped by the gestures of disturbance. Take Killing<br />

<strong>Time</strong> (2017), for instance: a series of wall hangings composed of single<br />

and hinged handcuffs decorated with costume jewelry, gold-plated chains,<br />

feathers, fake pearls, and shiny cubic zirconia. The cuffs and delicate expanses<br />

of chain unravel across the wall, calling attention to the transitional<br />

functions of the prison industrial complex as they unevenly impact Black<br />

people. As handcuffs are used to temporarily limit movement of subjects<br />

accused of transgressing the law, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s instruments of restraint are<br />

fashioned to form a precarious relationality pieced together through thinly<br />

constituted chains. Their juxtapositions, excesses, and scale position us at<br />

the crossroads of pain and pleasure particular to Black life.<br />

In Killing <strong>Time</strong>, <strong>Olujimi</strong> cites and departs from Melvin Edwards’s<br />

phenomenal Lynch Fragments (1963–ongoing). This series of relief sculptures,<br />

composed of layered and entwined metal chains, fragments, and<br />

industrial objects sometimes used in acts of anti-Black violence, calls<br />

attention to the weight of such bodies of pain. Departing from Edwards,<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong> installs cuffs in plain view, making the conditions of such violence<br />

unavoidable to his audience. In <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work, as in Edwards’s, there’s a<br />

call to think about the ways that power manifests relations between subjects<br />

8 9