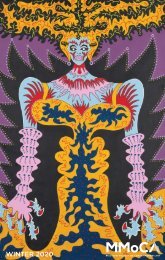

Kambui Olujimi: Zulu Time exhibition catalog

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

This catalog is from the installation of this exhibition at MMoCA. It includes essays by Sampada Aranke, Leah Kolb, and Gregory Volk.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

MADISON MUSEUM of<br />

CONTEMPORARY ART

FAILURE<br />

to LAUNCH<br />

Temporal Suspense in<br />

<strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong><br />

Sampada Aranke<br />

There is a thin line between explosion and implosion in <strong>Kambui</strong><br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong>’s <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>. Structures and materials are mobilized in ways<br />

that confuse the boundary between these two forms of destruction.<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong> leaves us with more than destruction, however. He imparts a<br />

renewed set of sensations that relish in the indeterminacy of construction<br />

and deconstruction, a suspended examination of power’s temporal<br />

dimension<br />

Part of what is at play in <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work is an understanding of<br />

the contingency of power. This is best evidenced in T-Minus Ø (2017),<br />

a set of 13 digitally printed cotton flags that feature images of failed<br />

rocket launches. Since military research and the conquest of space are<br />

usually presented as progressive if not utopic explorations undertaken<br />

for scientific knowledge, the rocket becomes the perfect surrogate for<br />

nationalist—and by extension masculinist—vitality. 1 The work of<br />

nationalism is metaphorized through space exploration, and in this vision<br />

of the future, the rhetorics of conquest and settlerism work against<br />

those racialized and gendered bodies who will be left behind.<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong> takes the rocket’s promise and disturbs it, then; the<br />

rocket’s phallus wryly signals the doubleness of failed explosion as<br />

an ejaculation gone wrong for the nation and therefore for mankind.<br />

Each flag features one historic failed launch, the images of which are<br />

manipulated by the artist, layered upon themselves, and echoed in<br />

their repetitive presentation. What we see is multiple and spectacular<br />

attempted takeoffs: the pyrotechnics of failure right before the moment<br />

of collapse. What we’re given is a commentary on our current political<br />

moment not as exceptional nor isolated, but rather as part of a broader<br />

system of power in which our political present is a manifestation of the<br />

long durée of history itself.<br />

T-Minus Ø comments on the deep resonances between science<br />

and politics, space and nation, universality and patriotism. <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

arranges these flags so as to proffer a salute, or at least a quiet repose,<br />

in which the viewer is asked to consider how the ambitions of scientific<br />

innovation might mark an affiliation with those nationalist and militaristic<br />

impulses that set these rockets in air. Importantly, these iterative<br />

objects stand in stillness indoors, taken out of their landscapes and<br />

stuck endlessly in their failures to launch. Throughout <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work,<br />

time is trapped in the moment of explosion, at once spectacular and yet<br />

eerily static, a moment stuck without resolution.<br />

These are <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s time bends in <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>. In his work,<br />

time sticks, suspends, holds still. Moments are anticipated, but never<br />

fully activated. Coordinated Universal <strong>Time</strong> (UTC), referred to commonly<br />

as <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>, is a “universal” way of marking time, in which<br />

zero is the point of departure for hours, minutes, and seconds. Standard<br />

timekeepers have adopted UTC as the normative mode of time,<br />

therein reinforcing the West as timekeeper of modernity. 2 Experts<br />

insist that this use of “<strong>Zulu</strong>” has no direct relation to the Bantu people<br />

of South Africa and that the word is merely adopted from NATO’s phonetic<br />

alphabet in which the letter “Z” is signaled through “<strong>Zulu</strong>.” However,<br />

the naming points us to colonial methods of timekeeping used<br />

1. For more information on the intersections<br />

between space exploration, popular culture,<br />

and gendered representations, see: Constance<br />

Penley, NASA/TREK: Popular Science and<br />

Sex in America (London: Verso Books, 1997);<br />

Daniel Sage, How Outer Space Made America:<br />

Geography, Organization, and the Cosmic<br />

Sublime (London: Routledge, 2016); Peter<br />

Dickens and James S. Ormrod, eds., The Palgrave<br />

Handbook of Society, Culture and Outer<br />

Space (London: Palgrave, 2016).<br />

2. Jean Baudrillard, “Modernity,” in Encyclopaedia<br />

Universalis Vol. 12, trans. David James<br />

Miller (Paris: Encyclopaedia Universalis<br />

France, 1985), 424–426; Edward Said, Orientalism<br />

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1997).<br />

3. “Military & Civilian <strong>Time</strong> Designations,”<br />

<strong>Time</strong> Zones | Greenwich Mean <strong>Time</strong>, accessed<br />

February 27, 2017, https://greenwichmeantime.com/info/timezone/.<br />

6 7

y conquest cultures and reflects Western visions of the African continent.<br />

Modernity’s aesthetic wing, shorthanded as modernism, relies upon traditions<br />

and practices that have notoriously fixed the nonwhite body within<br />

temporal stasis, if not regression, through representational traps that tarry<br />

between hypervisible and invisible, undesirable and lasciviously sexual.<br />

Modernism tends to maintain the temporal logics of modernity, which lock<br />

the Black body into a temporal logic of regression— the stereotype of the<br />

savage left behind by the West, and therefore stuck in History and therefore<br />

lagging behind in narrative progression. 4<br />

In light of this, <strong>Olujimi</strong> flips the script. He uses <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> as a<br />

point of departure, considering the ways that Blackness itself might always<br />

be imbedded in modernity’s logics of time and, by extension, structures<br />

of power. In other words, <strong>Olujimi</strong> suggests that “<strong>Zulu</strong>” being the name<br />

for a universal system of timekeeping is no coincidence. Because the word<br />

connotes a people whose anticolonial history has been oft-cited in Black<br />

freedom struggles across the world, “<strong>Zulu</strong>” connects Blackness to the field<br />

of temporal play. <strong>Olujimi</strong> calls attention to these vestiges in the structuring<br />

of everyday contemporary life, and, by extension, illuminates modernism’s<br />

role in the consolidation of white supremacy today. His is an anachronistic<br />

4. For more on the relationship between temporality,<br />

colonialism, and empire as it unevenly<br />

impacted African diasporic subjects, see: Anne<br />

McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and<br />

Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (New York:<br />

Routledge, 1995); Keya Ganguly, “Temporality<br />

and postcolonial critique,” in The Cambridge<br />

Companion to Postcolonial Literary Studies, ed.<br />

Neil Lazarus (New York: Cambridge University<br />

Press, 2004),162–182; Simon Gikandi, “Globalization<br />

and the Claims of Postcoloniality,” South<br />

Atlantic Quarterly 100, no. 3 (2001): 627–658;<br />

Barbara Fuchs and David J. Baker, “The Postcolonial<br />

Past,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly<br />

65, no. 3 (2004): 329–340.<br />

Black-aesthetic practice that takes time out of sync, and settles in the impasse<br />

of irreconcilable liminality. In this visual formulation, time becomes<br />

a mechanism through which we understand power through sight—what we<br />

see is not only what we get, but also what was given to us.<br />

To mobilize this kind of sight through <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s works is to suspend<br />

oneself between explosion and implosion, and ultimately to practice<br />

modes of relationality gripped by the gestures of disturbance. Take Killing<br />

<strong>Time</strong> (2017), for instance: a series of wall hangings composed of single<br />

and hinged handcuffs decorated with costume jewelry, gold-plated chains,<br />

feathers, fake pearls, and shiny cubic zirconia. The cuffs and delicate expanses<br />

of chain unravel across the wall, calling attention to the transitional<br />

functions of the prison industrial complex as they unevenly impact Black<br />

people. As handcuffs are used to temporarily limit movement of subjects<br />

accused of transgressing the law, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s instruments of restraint are<br />

fashioned to form a precarious relationality pieced together through thinly<br />

constituted chains. Their juxtapositions, excesses, and scale position us at<br />

the crossroads of pain and pleasure particular to Black life.<br />

In Killing <strong>Time</strong>, <strong>Olujimi</strong> cites and departs from Melvin Edwards’s<br />

phenomenal Lynch Fragments (1963–ongoing). This series of relief sculptures,<br />

composed of layered and entwined metal chains, fragments, and<br />

industrial objects sometimes used in acts of anti-Black violence, calls<br />

attention to the weight of such bodies of pain. Departing from Edwards,<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong> installs cuffs in plain view, making the conditions of such violence<br />

unavoidable to his audience. In <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work, as in Edwards’s, there’s a<br />

call to think about the ways that power manifests relations between subjects<br />

8 9

Above:<br />

Melvin Edwards<br />

Some Bright Morning, 1963<br />

Welded steel<br />

14.5 x 9.3 x 5 inches<br />

(36.83h x 23.62w x 12.7d cm)<br />

Courtesy Alexander Gray<br />

Associates, New York<br />

© 2017 Melvin Edwards/<br />

Artists Rights Society (ARS),<br />

New York<br />

Facing:<br />

Stowaway, from Killing <strong>Time</strong><br />

whose bodies are made temporally present by these cuffs, while nevertheless<br />

absent from their presentation. Put another way, in order to meet their<br />

function, the cuffs necessitate wrists which are themselves made present<br />

here only by their absence.<br />

Killing <strong>Time</strong> activates the suspension of time as mediated through<br />

the prison industrial complex, best understood as the relationship between<br />

prisons, courts, policing, criminalization, and surveillance that anticipates<br />

and exceeds prison walls. The prison industrial complex relies upon<br />

a durational understanding of time, where punishment is determined by<br />

fantastical algebras of equivalence: prison sentences are calculated through<br />

irrational ratios of time, as evidenced by sentences that amount to multiple<br />

lifetimes inside prison walls. “Doing time” becomes shorthand for serving<br />

out one’s sentence, a formula where time is a form of waiting with no<br />

guaranteed endpoint. With Killing <strong>Time</strong>, <strong>Olujimi</strong> takes this logic of time in<br />

a different direction, suggesting that to kill time is to do time, while waiting<br />

to make use of time, while waiting for time to pass.<br />

Further, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s cuffs and accessories suggest that time is a<br />

practice of relationality mobilized through the proximity to power structures<br />

that make us subjects. However, relationality is by no means overdetermined<br />

by those powers. The blinged-out, decadent objects networked by<br />

10 11

12 13

shiny chains blur the boundaries between pain and pleasure. They annotate<br />

handcuffs and jewelry as two kinds of excess: on the one hand,<br />

the forms of structural violence as made evident by the prison industrial<br />

complex, and, on the other, the pleasurable decadence of embellished<br />

jewelry. Both are worn, both require the cold touch of metal on flesh.<br />

This relationality exists within temporal suspense: disturbing gestures<br />

of time-keeping that are unquestionably Black.<br />

Blackness means doing time in a particular way. For <strong>Olujimi</strong>,<br />

this way is through anachronism, a method of historical collision in<br />

which the past cannot escape its present. <strong>Olujimi</strong> materializes this<br />

collision through overlay and juxtaposition such that time stands still,<br />

freezes momentarily so as to enable a moment of reflection, thought,<br />

gathering. Operating as a clock of his own making, <strong>Olujimi</strong> arrives at<br />

the task of timekeeping and asks us to reconsider how radical Black<br />

aesthetic interventions open up impossible possibilities which may,<br />

if we’re lucky, rupture time itself, collapsing past, present, and future<br />

altogether.<br />

1, 2, 13, 14, front<br />

and back covers:<br />

Untitled (detail),<br />

from T-Minus Ø<br />

4–5, 8–9, 13, 14:<br />

T-Minus Ø<br />

(installation view)<br />

12:<br />

Fathom (detail)<br />

14 15

POETICS<br />

of (IN)VISIBILITY<br />

Leah Kolb<br />

In <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>, <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong> presents a body of work that<br />

plays with notions of visibility, gesturing towards socio-economic<br />

infrastructures and political systems whose authority relies on the very<br />

absence of detectability. In a clever parallel, <strong>Olujimi</strong> similarly disguises<br />

his artwork’s own power by eschewing the literal. In refusing to give<br />

visual form to what he specifically references, the artist asks us to<br />

look behind, around, under, and through his objects and images—to<br />

consider what might be absent or obscured as much as what is present<br />

and tangible. His artworks become simultaneous presentations of<br />

visibility and invisibility, and demand a metaphorical slowing down of<br />

time to allow for careful, contemplative observation.<br />

<strong>Time</strong> itself manifests as the most invisible yet pervasive<br />

force in this <strong>exhibition</strong>. <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>—the phonetic pronunciation of<br />

Z-<strong>Time</strong>—refers to Coordinated Universal <strong>Time</strong> (formerly Greenwich<br />

Mean <strong>Time</strong>), the world’s standardized mode of tracking time. Specifically,<br />

it references the time at the prime meridian (longitude 0 degrees),<br />

the invisible and ultimately arbitrary line from which all global time<br />

zones are calculated. Since Great Britain was the world’s foremost<br />

maritime power when the concept of latitude and longitude originated,<br />

the starting point for designating longitude is based on the location<br />

of the British Naval Observatory. Thus, <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> literally revolves<br />

around Western norms for structuring a day. 1 This notion of universal<br />

time as an intangible yet ever-present expression of dominance and<br />

an imposition of control—a residue of Empire—serves as <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s<br />

jumping off point for creating two- and three-dimensional works that<br />

explore entrenched hierarchies and power disparities, while questioning<br />

assumptions underlying our understanding of the world at large.<br />

Consider InDecisive Moments, a series of four hourglassshaped<br />

vessels with craggy protrusions, resembling icebergs, that<br />

extend inward on either end. The bottom section of each hourglass<br />

is partially filled with water, further reinforcing the visual allusion<br />

1. Dava Sobel details the politics, history, and<br />

science of global mapping and timekeeping<br />

in Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius<br />

Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of<br />

His <strong>Time</strong> (New York: Penguin Books, 1995).<br />

Regarding the arbitrary nature of the prime<br />

meridian, she writes: “As the world turns, any<br />

line drawn from pole to pole may serve as well<br />

as any other starting line of reference. The<br />

placement of the prime meridian is a purely<br />

political decision.” (4).<br />

17

to those floating mountains of ice whose exposed peaks belie their<br />

massive underwater heft. Contrasting medium and message, <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

uses glass, an inherently transparent material, to create sculptures that<br />

remind us of a natural phenomenon whose real danger lies hidden beneath<br />

the surface. This visual pun serves as a metaphor for the opaque<br />

policies that privilege some while destroying others. In other words,<br />

the injustices we can see are only the “tip of the iceberg,” while the true<br />

source of America’s systemic and racially determined discrimination<br />

is the country’s structural foundation. 2 Indeed, centuries after the<br />

country’s founding, inequitable core principles continue to influence<br />

through unfair policies and political violence. 3<br />

The sculptures comprising InDecisive Moments recall both<br />

geological formations (icebergs) and methods for time keeping<br />

(hourglasses). <strong>Olujimi</strong> ascribes this visual convergence to his interest<br />

in the scientific notion of “deep time,” from which springs our modern<br />

conception of geological time—that “immense arc of non-human<br />

history” that accounts for the formation of the earth itself. Impossible<br />

to comprehend within the scale of human time, deep time reveals the<br />

imperceptible forces that shaped the world as we currently perceive it:<br />

the record of continents moving and reshaping, of mountain ranges<br />

rising and falling, and of glaciers—the source of icebergs—transforming<br />

topographies. 4<br />

In the work titled The Black That Birthed Us <strong>Olujimi</strong> again<br />

brings us out of human time to consider the elemental systems<br />

underlying all life. Twenty-five large sheets of printed paper have been<br />

attached to the gallery wall to reveal a composite image of star clusters<br />

and intergalactic dust. The work can be read as an homage to the big<br />

2. Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a succinct and<br />

numerical summary of America’s racially directed<br />

policies towards its Black population:<br />

“Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety<br />

years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate<br />

but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing<br />

policy.” Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for<br />

Reparations,” The Atlantic, May 24, 2014.<br />

3. Structural racism refers to the normalization<br />

and legitimization of historical, cultural,<br />

institutional, and interpersonal policies,<br />

practices, and attitudes that perpetuate and<br />

produce cumulative, chronic adverse outcomes<br />

for people of color. Keith Lawrence and<br />

Terry Keleher, “Chronic Disparity: Strong<br />

and Pervasive Evidence of Racial Inequalities:<br />

Poverty Outcomes: Structural Racism”<br />

(paper presented at the National Conference<br />

on Race and Public Policy, Berkeley, CA,<br />

November 2004).<br />

4. David Farrier, “How the Concept of Deep<br />

<strong>Time</strong> is Changing,” The Atlantic, October 31,<br />

2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/<br />

archive/2016/10/aeon-deep-time/505922/.<br />

bang theory, which explains how the universe developed from a tiny,<br />

dense state into what it is today, including the most basic forces in<br />

nature, from electromagnetism to gravity. The science of the big bang<br />

and of deep time have enabled us to construct an encompassing view<br />

that places human history in the context of scientific historiography—<br />

a way to perceive what could not otherwise be seen.<br />

On the wall facing The Black That Birthed Us is a second<br />

composite image made from another set of 25 sheets of paper. Rather<br />

than conjuring associations to those forces outside of time that have<br />

impacted how we see the earth, Ville Radieuse, habite-à-machine (The<br />

Radiant City, the living machine) presents a view of the very human<br />

forces—situated within the perceivable chronology of historic time—<br />

that covertly direct the course of our lives.<br />

This installation pictures the implosion of St. Louis’s Pruitt-<br />

Igoe housing projects, the now-infamous public housing structures<br />

that stood as towering symbols of inner-city poverty before being<br />

demolished in the 1970s. But <strong>Olujimi</strong> does not simply replicate the<br />

archival image in large scale. Instead, he digitally alters it with visual<br />

echoes and stutters—blurring, multiplying, shrinking, cropping, and<br />

overlapping the image onto itself so that it bounces back and forth<br />

between clarity and obfuscation. He uses an image within an image<br />

within an image to represent the notion of a system within a system<br />

within a system. Thus, the formal attributes of this piece complement<br />

the artist’s conceptual point that inequalities, including housing<br />

inequalities, exist not on a single plane with one-point perspective,<br />

but within multiple contexts and facets that interact and interconnect,<br />

positioned on top of and within each other; some visible, some<br />

distorted, and some beyond sight.<br />

Familiar narratives constructed around the failures of<br />

Pruitt-Igoe blame modernist architecture, public assistance programs,<br />

or the predominantly Black residents themselves. 5 With Ville<br />

Radieuse, habite-à-machine, however, <strong>Olujimi</strong> offers a more complex<br />

reading. He suggests that focusing on the visible elements at the surface<br />

of the narrative—the architectural design of the project, public welfare<br />

programs, the inhabitants of the building—conveniently blinds us to<br />

the larger contextual forces at play: the economic decline of post-World<br />

War II urban St. Louis, and the city’s public policies and insidious<br />

18 19

private strategies that effectively sorted and zoned the population by<br />

race. 6 We also ignore the fact that this “urban renewal” plan did not<br />

set forth an adequate strategy for funding and maintaining its massive<br />

public housing project, nor did it stimulate the economic development<br />

necessary for Pruitt-Igoe’s residents to financially succeed. Instead, by<br />

tying the structural upkeep of the building to the tax base of its residents,<br />

city leaders all but guaranteed a continuing cycle of poverty and<br />

deterioration. Further, the 57-acre site within which the 33 apartment<br />

complexes were situated was never integrated into the infrastructure<br />

of downtown St. Louis: the original architectural plans for traffic and<br />

pedestrian thoroughfares connecting Pruitt-Igoe’s community to the<br />

larger city were deemed too expensive to execute. Thus, Pruitt-Igoe and<br />

its inhabitants were left to live in what became a wasteland of concrete<br />

towers isolated from the larger world—a metaphorical prison. 7<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong> explores the connection between human economies<br />

and imprisonment in another body of work within the <strong>exhibition</strong>, a<br />

series of altered handcuffs collectively titled Killing <strong>Time</strong>. Rather than<br />

being joined by a chain these cuffs are linked together with ornamental<br />

strands of rhinestones and costume jewelry, thereby transforming an<br />

object of restraint into one of wearable fashion. The physicality of these<br />

objects and their implied relationship to the human body, as circling<br />

both the wrists and the neck, functions to animate the works, breathing<br />

life into the law-and-order policies that disproportionately target<br />

and incarcerate men of color. 8<br />

5. Originally conceived of and designed as<br />

segregated housing complexes, Pruitt Igoe<br />

opened in 1955 as racially integrated, owing<br />

to the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling<br />

in Brown vs. Board of Education, which<br />

deemed unconstitutional the legal practice of<br />

“separate but equal” segregation. In practice,<br />

however, racial integration within Pruitt-Igoe<br />

remained minimal, and segregation became<br />

a de facto reality: by the late 1960s, Pruitt<br />

Igoe’s population was 98% Black. This can be<br />

attributed to many factors, including whiteflight<br />

to the suburbs and city’s long history<br />

of racism and segregated housing practices.<br />

See: Elizabeth Birmingham, “Refraining the<br />

ruins: Pruitt-Igoe, Structural Racism, and<br />

African American Rhetoric as a Space for<br />

Cultural Critique,” Western Journal of Communication<br />

63, no. 3 (1999): 291-309; Mary<br />

C. Comerio, “Pruitt Igoe and Other Stories,”<br />

Journal of Architectural Education 34, no. 4<br />

(1981): 26-31.<br />

6. The 1949 Housing Act that funded the<br />

development of Pruitt-Igoe was used as a<br />

tool of racial segregation and as justification<br />

for the clearance of impoverished neighborhoods<br />

in downtown St. Louis. Discriminatory<br />

practices such as redlining further deepened<br />

existing patterns of racial segregation.<br />

The Myth of Pruitt-Igoe, directed by Chad<br />

Freidrichs (2011; St. Louis, MO: First Run<br />

Features, 2012), DVD.<br />

7. For a more comprehensive evaluation on the<br />

social, political, and economic forces that<br />

contributed to the failure of Pruitt-Igoe,<br />

see, for example: Katherine G. Bristol, “The<br />

Pruitt-Igoe Myth,” Journal of Architectural<br />

Education 44, no. 3 (1991): 163-71.<br />

21

22 23

Absent physical bodies, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s modified cuffs could be<br />

mistaken for jewelry on display, commodities for purchase. Formally,<br />

the lyrical line work of the draping jewelry recall labyrinthine networks<br />

of commercial trade routes, a possible allusion to the commodification<br />

of human life during America’s 250-year history of slavery. A visual<br />

reminder of the global economy of the slave trade, Killing <strong>Time</strong> can be<br />

read as a metaphorical map of stolen time and lost lives. These works<br />

also gesture toward a much more contemporary capitalistic endeavor:<br />

the economics of our criminal justice system. In the astute words of<br />

scholar and activist Angela Davis, prisons perform a “feat of magic”<br />

by tricking people into thinking that disappearing vast numbers of<br />

human beings is the same thing as disappearing the social problems<br />

that result from ingrained racism and the cycle of poverty. This act of<br />

rendering people invisible by placing them effectively out of sight is<br />

highly profitable for private industries providing goods and services to<br />

those behind bars. 9 But as glittering reminders a system that enriches<br />

some through the forced imprisonment of others, the works in Killing<br />

<strong>Time</strong> suggest that our present approach to crime and punishment has<br />

effectively re-commodified human life.<br />

Perhaps, then, it is appropriate to conclude this essay with<br />

discussion of <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s installation titled T-Minus Ø, a dignified arrangement<br />

of thirteen flags, each displaying violent explosions of failed<br />

rocket launches. Whether or not <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s objective was to circle back to<br />

the legacies of Western colonialism by alluding to the original thirteen<br />

British colonies in North America, the flags nevertheless vibrate with<br />

nationalist intention. In the United States, we make public affirmations<br />

of loyalty to our flag, which we see as a symbol of our country, our history,<br />

and our pride in both. But if a flag represents such an idea, or even<br />

an ideal, what exactly are we are being asked to salute? The veiled legacy<br />

of a dehumanizing economy? <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s flags, with their grand imagery<br />

of collapse, point to the failures in our nationalist agenda, both past and<br />

present, visible and invisible. With T-Minus Ø, <strong>Olujimi</strong> suggests that we<br />

are, indeed, out of time; that we have entered a moment in time when we<br />

must face those failures, acknowledge the subtleties of institutionalized<br />

biases, and make visible those bodies that are being kept out of sight<br />

through underhanded strategies of subjugation.<br />

8. Garrick L. Percival cites numerous studies<br />

showing Blacks are 6 to 8 times more likely<br />

to be incarcerated relative to whites, and<br />

Hispanics are 3 ½ times more likely to be<br />

incarcerated than whites. Garrick L. Percival,<br />

“Ideology, Diversity, and Imprisonment:<br />

Considering the Influence of Local Politics<br />

on Racial and Ethnic Minority Incarceration<br />

Rates,” Social Science Quarterly 91, no.4<br />

(2010): 1064-1082. See, also, Leah Sakala,<br />

“Breaking Down Mass Incarceration rates in<br />

the 2010 Census,” https://www.prisonpolicy.<br />

org/reports/rates.html.<br />

9. Angela Davis, “Masked Racism: Reflections<br />

on the Prison Industrial Complex,” in Race,<br />

Class, and Gender in the United States (7th<br />

edition), ed. Paula S. Rothenberg (New York:<br />

Worth Publishers, Inc., 2007), 683-87.<br />

16, 21:<br />

Ville Radieuse, habiteà-machine<br />

(The Radiant<br />

City, the living machine)<br />

(installation detail)<br />

22–23:<br />

The Black That Birthed Us<br />

(installation detail)<br />

24 25

30

28, 29:<br />

The Drop, from<br />

InDecisive Moments<br />

30, 32:<br />

The Chase, from<br />

InDecisive Moments<br />

31, facing:<br />

A Sheltered Wish, from<br />

InDecisive Moments<br />

33:<br />

Blue Ebb, from<br />

InDecisive Moments<br />

32

ZULU<br />

TIME<br />

On the Art of <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

Gregory Volk<br />

Along with many artists of his generation, <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

often deals in found objects and Internet images. He has, however,<br />

a transformative—at times almost magical—way of reconfiguring<br />

these objects and images into artworks that defy easy categorization:<br />

sculptures, flags, and large-scale wall works incorporating transmuted<br />

photographs; sculptures that have attributes of painting and drawing;<br />

protean sculptures with variable dimensions. These works are<br />

suffused with ideas about race, class, politics, urban environments,<br />

space exploration, cosmic structures, history, nature and the sublime,<br />

and technology. <strong>Olujimi</strong> is an expansive thinker and eclectic research<br />

underpins his projects. He is also a consummate maker who lavishes<br />

attention on all aspects of his works. Characterized by a concentrated<br />

engagement with forms and materials, these works emanate a peculiar<br />

power. Granted, they are sculptures or photographic images, but they<br />

also operate as uncanny forces.<br />

Stowaway (2017), one of several wall sculptures from <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s<br />

ambiguously titled Killing <strong>Time</strong> series, seems at first lovely and stately.<br />

Silver, gold, and black metal circles, a small blue ball (almost like a<br />

mini-globe), black brocade, and a gleaming, multicolored pendant<br />

form an exquisite mesh of textures, colors, and shapes. This austere<br />

yet lush work rivets one’s attention like some sort of potent talisman.<br />

With Never Adds Up (2017), four metal circles are arrayed on the wall.<br />

Descending from each and connecting the whole work are gracefully<br />

curving silver and gold chains, a gold braid, earrings, glittery trinkets,<br />

and blue beads. Solitaire (2017) is even more elaborate, arcing up the<br />

wall with multiple circles, curving strands, pendants, and assorted<br />

small objects.<br />

34 35

Although these works register as largely abstract, they are<br />

made of non-abstract objects from the world at large, as opposed to<br />

components created by the artist in his studio. They loosely hint at<br />

human figures—perhaps even totemic figures or deities—with circles<br />

suggesting heads and strands and chains suggesting bodies and limbs.<br />

Elegantly sweeping across the wall, these strands and chains also<br />

resemble the gently arching lines drawn on maps to indicate great circle<br />

routes—the shortest distance between two points on the surface of a<br />

sphere. Although great circle routes appear arched on two-dimensional<br />

maps, the actual flight paths are straight lines along our threedimensional<br />

earth.<br />

<strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>, the title of the <strong>exhibition</strong>, similarly signals a<br />

clash between different systems of information and different ways of<br />

representing the world. This is the military and civil aviation term for<br />

Coordinated Universal <strong>Time</strong> (UTC), an even more accurate calibration<br />

that supersedes Greenwich Mean <strong>Time</strong> (GMT). Based on zero degrees<br />

longitude, which runs through the Royal Naval Observatory southeast<br />

of London, GMT originated in the nineteenth-century during the<br />

heyday of the British Empire when Great Britain fancied itself as the<br />

center of the world. It is paradoxical and ironic, to say the least, that<br />

the term <strong>Zulu</strong> time points inescapably to the <strong>Zulu</strong> people of Southern<br />

Africa, who fiercely battled the invading British in late 1878 and 1879<br />

before being brutally defeated and colonized. However unwittingly,<br />

this term is encoded with conquest, colonialism, ethnic and racial<br />

identity, and flat out racism.<br />

Look more closely at the works I’ve mentioned and you<br />

discover—perhaps you are startled to discover—exactly what the<br />

materials are. The metal circles are actual handcuffs. They come with<br />

shuddering connotations. In this era of devastating mass incarceration,<br />

these are the restraining devices routinely used by (predominately<br />

white) police officers on (disproportionally black) arrestees. They<br />

are not a symbol of power and subjugation, but rather the actual tools<br />

used by the powerful to subjugate others, tools at the front lines of<br />

systemic racism. That’s one reference. Another is to the gruesome<br />

shackles and manacles used—again routinely—in crammed ships,<br />

auction blocks, and plantations throughout the centuries-long ordeal<br />

of the Middle Passage. The other elements of these works are low-end<br />

costume jewelry, not Cartier or Bulgari from the flagship stores where<br />

the wealthy (largely white) people shop, but affordable adornments<br />

from the neighborhood. Still, this lowbrow bling does not look<br />

tacky, trashy, or abased. Instead it looks downright resplendent.<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong>’s works allow you see how transformative and<br />

disruptive he really is, as he shifts familiar objects from their normal<br />

contexts, positions, and functions, combining them not just into fresh<br />

and surprising new conditions, but also into a fresh and surprising<br />

new life. Otherwise threatening and scary handcuffs now look fanciful<br />

and inviting. Cheap costume jewelry looks energetic and bedazzling.<br />

Small, enthralling, sensual details abound: a single pearl nestled<br />

against one link in a gold chain, the sensitive way that a light blue<br />

teardrop earring reflects both light and neighboring gold chains.<br />

36 37

38

In fact, there is a great deal of visual poetry in <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s<br />

work—tiny catharses, moments of retinal splendor. His chandelier<br />

installation, titled Fathom (2017), is likewise transformative and<br />

disruptive. Typically identified with (white) privilege and wealth,<br />

chandeliers normally hang high overheard. In <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s sculpture, six<br />

ornate and opulent working chandeliers have been jarringly dislocated<br />

from their usual position and context. Now on the floor, they retain<br />

a residual elegance but also look ungainly and precarious. They are<br />

much closer now, not remote and magisterial, but right here, next<br />

to us, intimate chandeliers suggesting human bodies with slightly<br />

sagging postures. On the floor, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s chandeliers function not just<br />

as sources of light but also as fragile sources of power. The chandeliers<br />

rest like figures on a structure that refers to the improvised crafts<br />

used by refugees as they make dangerous ocean voyages. Fathom thus<br />

addresses a political and moral crisis. At a time when millions of<br />

vulnerable refugees are desperately seeking some measure of solace<br />

and safety, virulent hostility to immigrants is a rising force in many<br />

countries, including the United States.<br />

Importantly, despite their completely altered conditions,<br />

these chandeliers continue to function as they normally would; they<br />

continue to illuminate the room, or at least parts of it. This helps<br />

explain why <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s art is so distinctive, especially when it comes to<br />

his use of found objects and images. His objects—be they a chandelier,<br />

handcuffs, earrings, necklace, or photograph—retain a residual<br />

familiarity that points to their original function, while simultaneously<br />

existing as completely transformed. <strong>Olujimi</strong> leaves it for the viewer<br />

to move between these two contexts, the one familiar and at times<br />

mundane, and the other eccentric, destabilizing, misbehaving, and<br />

invigorating.<br />

Here it is worth recalling the great Russian literary critic and<br />

philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975), and his idea of the carnival,<br />

which he applied to literature (especially to Dostoevsky’s novels),<br />

but which can also be fruitfully applied to certain kinds of visual<br />

art, including <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s. 1 For Bakhtin, the “carnivalized moment” or<br />

“carnivalized situation” (or, in this context, the carnivalized object) are<br />

1. All quotes from and references to Mikhail<br />

Bakhtin are from his Problems of Dostoevsky’s<br />

Poetics, trans. Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis:<br />

University of Minnesota Press, 1984),<br />

122–124.<br />

Facing, 42–43:<br />

Fathom<br />

40

42 43

36, 37:<br />

Christmas Bus,<br />

from Killing <strong>Time</strong><br />

38–39:<br />

Litmus Test,<br />

from Killing <strong>Time</strong><br />

This page and facing:<br />

Solitaire,<br />

from Killing <strong>Time</strong><br />

44, 45:<br />

Never Adds Up,<br />

from Killing <strong>Time</strong><br />

when the normal rules, values, hierarchies, and modes of apprehension<br />

are temporarily suspended in favor of a new and radical freedom.<br />

This freedom can be simultaneously bewildering and illuminating,<br />

unsteadying and exhilarating. For Bakhtin, the carnivalized situation<br />

“… combines the sacred with the profane, the lofty with the low, the<br />

great with the insignificant, the wise with the stupid.” It involves a<br />

decisive upending of normal life with all its rules, categories, hierarchies,<br />

and stratification. Bakhtin called this “life drawn out of its usual<br />

rut” and “life turned inside out.” I’m not suggesting that <strong>Olujimi</strong> is<br />

beholden to Bakhtin, but rather that what Bakhtin might have called a<br />

“carnival impulse”—involving eccentricity, disruption, fresh identities,<br />

an elevation of humble things, a humbling of powerful things, and<br />

vigorous transformation—is essential in <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work, and indeed is<br />

a major reason why his artworks are so unusual and cathartic.<br />

As humans pursued ever more advanced rockets for space<br />

exploration, satellite transportation, and sophisticated weaponry,<br />

technological marvels have been attended by whopping failures, when<br />

rockets and missiles ignited into chaotic infernos. Images of these<br />

events are commonplace in the popular culture. For his wall installation<br />

consisting of flags from his T-Minus Ø series (2017), <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

selected Internet images of exploded rockets, with all their flash points<br />

and fireballs, hurtling debris and oddly delicate smoke tendrils. He<br />

44

46 47

Below:<br />

Frederic Edwin Church<br />

(American, 1826–1900)<br />

Twilight in the Wilderness,<br />

1860<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

framed: 124 x 185 x 13 cm<br />

(48 13/16 x 72 13/16 x 5<br />

1/16 in)<br />

unframed: 101.6 x 162.6 cm<br />

(40 x 64 in)<br />

The Cleveland Museum of<br />

Art, Mr. and Mrs. William<br />

H. Marlatt Fund 1965.233<br />

Facing:<br />

Untitled (detail),<br />

from T-Minus Ø<br />

digitally altered the images to create layered, composite works that are<br />

both found and meticulously constructed, and then digitally printed them<br />

on both sides of the flags. The images are harrowing, but they are also<br />

gorgeous, even sublime. Printed directly on cotton fabric, this imagery<br />

constitutes a highly unorthodox kind of digital-era painting sans paint.<br />

Furthermore, these twenty-first-century “paintings” of high-tech mayhem<br />

connect visually with Romantic nineteenth-century landscape paintings.<br />

One of <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s untitled flags from this series shows curving white smoke,<br />

billowing pink smoke, and delicate smoke tendrils tinged with turquoise.<br />

Like other works in the series, it evokes a nineteenth-century aptitude for<br />

vastness and wonderment in nature—think of the stunning white, blue,<br />

and orange skies of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840); the overwhelming,<br />

multicolored sky in Frederic Church’s masterpiece Twilight in the Wilderness<br />

(1860), and the many awe-inspiring paintings of the American West by<br />

Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) and Thomas Moran (1837–1926). Streaking<br />

across a deep blue sky, the smoke and debris, colored white, turquoise,<br />

dark red, orange, purple, and yellow, in the image on the back side of<br />

this same work, would look fine paired with any number of landscape<br />

paintings featuring similar colors and surging energies by J.M.W. Turner.<br />

Unlike traditional paintings, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s canvases extend from the<br />

wall on aluminum poles, thus providing more complexity and another layer<br />

of meaning. This row of flags resembles what one might see in a conference<br />

room at the United Nations, but instead of signifying countries, the flags<br />

display disaster after disaster. In a time when so much of the world is<br />

convulsed by strife, and when the utopian promise of a gorgeous, high-tech<br />

future seems deeply suspect, this work by <strong>Olujimi</strong> is exceptionally apt.<br />

View <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s wall-sized composite photograph Ville<br />

Radieuse, habite-à-machine (The Radiant City, the living machine), 2017,<br />

with Bakhtin’s notion of carnivalization in mind. The work is rooted in two<br />

familiar items: wheat-paste posters common on city streets and decorative<br />

wallpaper in a home. Twenty-five paper sheets form a rhythmic, almost<br />

percussive, image of the massive St. Louis housing project Pruitt-Igoe<br />

being detonated in 1972. Rarely has such a grand and monumental urban<br />

renewal project gone so wrong so quickly, and its demise is documented<br />

here with sagging buildings and erupting smoke. Pruitt-Igoe was the first<br />

major project for architect Minoru Yamasaki (1912–1986), an American of<br />

Japanese descent who later designed the World Trade Center. Pruitt-Igoe<br />

opened in 1954 and rapidly declined for socio-political reasons involving<br />

poverty, government neglect, incompetence, racial bias, and a chronic<br />

lack of funding for basic maintenance. Based on an iconic photograph of<br />

the project’s demolition, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s composite image revisits a signature<br />

historical event but also suggests that the issues surrounding Pruitt-Igoe<br />

remain pertinent. It also connects a planned, manmade disaster with<br />

world-shaping natural forces like earthquakes. On a neighboring wall,<br />

48 49

25 wheat-paste sheets form a complex, nearly pulsating, image of<br />

outer space, including abundant stars and galaxy clusters. Titled<br />

The Black That Birthed Us (2017), this work gives a fresh and vast<br />

meaning to the idea of blackness, which is now linked with the<br />

universe. One work is from Earth, the other is cosmic, and both evince<br />

eternal cycles of creation and destruction, cohesion and entropy.<br />

In addition to <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s surprising connection with the<br />

19th century nature-based view of the sublime, he also, surprisingly,<br />

connects with Transcendentalist poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo<br />

Emerson (1803–1882). Emerson advocated immersive experiences<br />

in nature that could then be channeled into writing and art; this<br />

directive greatly inspired many of the preeminent landscape painters<br />

of his day. <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s immersive experiences are not with nature per<br />

se, but instead with mediated nature, and many of his works offer<br />

a mediated sublime, including his wonderful iceberg sculptures.<br />

Icebergs fascinate us, in part, because such a small part of<br />

the whole structure is normally visible above the surface of the water.<br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong>’s iceberg sculptures from the series InDecisive Moments (2017),<br />

meticulously crafted from glass and with hourglass shapes, are based<br />

on photographs of icebergs that show both their protruding tops and<br />

their great, looming, underwater bulk. Things overt and hidden,<br />

nature and technology, photography and sculpture, abstraction and<br />

representation all conjoin with talismanic force in <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s small glass<br />

sculptures. The hourglass shape is also telling, and ominous. Global<br />

warming is likely the most pressing issue facing the world today, as<br />

icebergs break off from Greenland and Antarctica. As gorgeous as<br />

they are, and as seductive, <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s iceberg sculptures constitute a<br />

warning. <strong>Time</strong> to address this impending ecological crisis is running<br />

out. <strong>Time</strong> is running out as well on the anthropocentric fantasy that we<br />

humans—comparatively recent additions to a planet more than four<br />

billion years old—are somehow above nature, or masters of nature.<br />

Addressing handcuffs and icebergs, rocket disasters, a housing<br />

complex, costume jewelry, outer space, climate change, and chandeliers,<br />

<strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong> is obviously a questing artist intent on making<br />

his own refreshingly idiosyncratic way and pursuing his own wideranging<br />

interests and obsessions. As such, he again connects with the<br />

visionary Emerson. “Art is the path of the creator to his work,” Emerson<br />

enigmatically wrote in his 1844 essay “The Poet.” For Emerson, art<br />

is not the finished painting, sculpture, or drawing; photograph or glass<br />

object; performance or musical score, but instead the comprehensive<br />

path that leads to all of those things: the artist’s individual way of<br />

working, thinking and being. This <strong>exhibition</strong> reveals that <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

is clearly on a path that matters, and that he is living, as opposed to<br />

just making, a spirited, challenging, and altogether compelling art.<br />

50 51

52 53

PROCESS OR<br />

INSTALLATION<br />

VIEW<br />

The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art is honored to<br />

publish this <strong>catalog</strong>ue in conjunction with <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s solo <strong>exhibition</strong><br />

in the museum’s State Street Gallery, from May 6 through August<br />

13, 2017. In <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>, the artist presents five interrelated<br />

bodies of work, each of which offers a thoughtful examination<br />

into the underlying structures that shape the way we understand and<br />

experience the world and each other. From the cosmic origins of the<br />

universe to today’s contested socio-political climate, <strong>Olujimi</strong> disrupts<br />

the space-time continuum and asks us to consider how historic and<br />

contemporary systems of power are deeply layered, interconnected, and<br />

mutually reinforcing.<br />

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the significant time and talent<br />

<strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong> has invested to make this project a reality. It has been a<br />

rewarding process to watch his ideas became tangible. For this <strong>exhibition</strong>,<br />

he created all new artworks that have yielded a visually cohesive<br />

and conceptually powerful <strong>exhibition</strong>. MMoCA is honored to showcase<br />

his work in its galleries.<br />

I am extremely grateful to the sponsors who have made this<br />

important project possible. Generous funding for <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong><br />

<strong>Time</strong> has been provided by The DeAtley Family Foundation; MillerCoors;<br />

Terry Family Foundation; WhiteFish Partners LLC; a grant from<br />

the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and<br />

National Endowment for the Arts; and MMoCA Volunteers.<br />

I would like to recognize and express my gratitude to the guest<br />

authors: Sampada Aranke, a scholar and professor in the History and<br />

Theory of Contemporary Art at the San Francisco Art Institute, whose<br />

essay grounds <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work within a theoretical framework; and New-<br />

York based art critic and curator Gregory Volk, who contributed an<br />

insightful essay about the transformative power of the artist’s practice.<br />

My thanks also go to Melissa Gorman for her design of the <strong>catalog</strong>ue,<br />

which seamlessly translates <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s artistic intentions into a beautiful<br />

publication. In addition, it is a particular pleasure to thank former<br />

MMoCA staff member Katie Kazan, who edited this publication.<br />

I am also pleased to acknowledge the museum’s Board<br />

of Trustees for their generous and continuing support. Finally, it is a<br />

great pleasure to recognize the talented staff of the Madison Museum<br />

of Contemporary Art, especially associate curator Leah Kolb, who organized<br />

and oversaw this project, with the dedicated assistance of <strong>exhibition</strong><br />

manager and registrar Mel Solomon Becker; Rick Axsom, senior<br />

curator; Brian Bartlett, technical services manager; Sheri Castelnuovo,<br />

curator of education; Erika Monroe-Kane, director of communications;<br />

Elizabeth Tucker, director of development; and the rest of MMoCA’s<br />

hard-working staff.<br />

Stephen Fleischman<br />

Director<br />

54 55

KAMBUI OLUJIMI<br />

was born and raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant Brooklyn and received<br />

his MFA from Columbia University in New York City. <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s work<br />

challenges established modes of thinking that commonly function<br />

as “inevitabilities.” This pursuit takes shape through interdisciplinary<br />

bodies of work spanning sculpture, installation, photography,<br />

writing, video, and performance. His solo <strong>exhibition</strong>s include: A<br />

Life in Pictures at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Solastalgia at Cue<br />

Arts Foundation, and Wayward North at Art in General. His works<br />

have premiered nationally at The Sundance Film Festival, Studio<br />

Museum in Harlem, MoMA P.S.1, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los<br />

Angeles and Mass MoCA. Internationally his work has been featured<br />

at The Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, Museo Nacional<br />

Reina Sofia in Madrid, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in<br />

Finland, and Para Site in Hong Kong, among others. <strong>Olujimi</strong> has<br />

been awarded residencies from Skowhegan School of Painting and<br />

Sculpture, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and Civitella Ranieri.<br />

He has received grants and commissions from numerous institutions<br />

including A Blade of Grass, The Jerome Foundation, and MTA Arts<br />

& Design for the City of New York. Newspapers and journals such<br />

as The New Yorker, Art Forum, Art in America, Brooklyn Rail, The<br />

New York <strong>Time</strong>s, and Modern Painters have written about <strong>Olujimi</strong>’s<br />

artwork. Monographs on his past projects include Walk the Plank<br />

(2006), Winter in America (in collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas,<br />

2006), The Lost Rivers Index (2007), and Wayward North (2012).<br />

Education<br />

2013 MFA, Columbia University School of the Arts, NY<br />

2006 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, ME<br />

Residencies<br />

2017 Robert Rauschenberg Residency, FL<br />

2015 Civitella Ranieri, Umbertide, Italy<br />

Meet Factory, Prague, Czech Republic<br />

LMCC: Process Space Residency, NY<br />

2013 Tropical Lab 7, Singapore<br />

2010-11 Acadia Summer Arts Program, ME<br />

Santa Fe Art Institute, NM<br />

2007-09 Fine Arts Work Center at Provincetown (2nd Year Fellow), MA<br />

2007 Apexart: Outbound Residency to Kellerberin, Australia<br />

Commissions / Awards<br />

2016 New York City MTA Arts & Design<br />

2015 Urban Glass Merit Scholarship<br />

2014 FSP/ Jerome Fellowship<br />

2013 A Blade of Grass, Artist File Grantee<br />

2010 Art in General’s New Works Commission<br />

Solo Exhibitions<br />

2017 <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong>, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI<br />

2016 What Endures, Catherine Clark Gallery, New York, NY<br />

Solastalgia, Cue Arts Foundation, New York, NY<br />

2015 What’s Left to Burn?, Bindery Projects, Minneapolis, MN<br />

2014 Blind Sum , Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York, NY<br />

A Life in Pictures, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Boston, MA<br />

The Conspiracy of Good People, Young World, Detroit, MI<br />

2012 A Life in Pictures, Apex Art, New York, NY<br />

2011 Love to Lose, Catherine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, CA<br />

2010 Wayward North, Art in General, New York, NY<br />

2009 The Clouds Are After Me, Saatchi & Saatchi, New York, NY<br />

2008 Winter in America, de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara, CA<br />

Selected Group Exhibitions<br />

2017 The Exposed Suture, Rond-Point Project, Marseille, France<br />

The Half-Life of Love, MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA<br />

More Than A Two Step, MoMA P.S.1 / For Freedoms Laboratory, NY<br />

2016 Paradoxical Stranger, Momo Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa<br />

2015 Draw: Mapping Madness, Inside Out Museum, Beijing, China<br />

Winter in America, Jack Shainman Gallery: The School, Kinderhook, NY<br />

2015: 1947, Artist Equity, New York, NY<br />

2014 Crossing Brooklyn, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, NY<br />

Performing for Cyclops, The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI<br />

2013 Mnemonikos, Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, Thailand<br />

2011 Pictures are Words-Not-Unknown, LiShui Museum of Photography,<br />

LiShui City, China<br />

2011-09 StreetWise, Museo Nacional Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain<br />

On Screen: Global Intimacy, Museo de Arte Carillo Gil, Mexico City, Mexico<br />

2010-09 Fax, The Drawing Center, New York, NY<br />

Selected Bibliography / Publications<br />

2016 All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party, Minor Matters,<br />

edited by Michelle Dunn Marsh pp. 54-7<br />

2015 Draw: Mapping Madness, Exhibition Monograph published by<br />

Inside/Out Museum, pp.152-3<br />

2012 Wayward North, Exhibition Monograph published by Art in General<br />

2011 Violence, Visual Culture, & the Black Male Body, Cassandra Jackson,<br />

published Routledge / UK, p.74<br />

2006 Frequency, The Studio Museum in Harlem, edited by Thelma Golden,<br />

pp. 82-3, 89<br />

Winter in America, 81 Press (W.I.A. is a collaboration with Hank Willis Thomas)<br />

Walk the Plank, Exhibition Monograph published by Gallery 138<br />

2000 Reflections in Black, W.W. Norton, edited by Deborah Willis, pp.247-8<br />

56 57

Contributors<br />

Sampada Aranke is an Assistant Professor in the History and<br />

Theory of Contemporary Art at the San Francisco Art Institute. Her work<br />

has been published in e-flux, Art Journal, Artforum, Equid Novi: African<br />

Journalism Studies, and Trans-Scripts: An Interdisciplinary Online Journal<br />

in the Humanities and Social Sciences at UC Irvine. Sampada and Nikolas<br />

Oscar Sparks (Duke University) have co-edited a special issue of Women<br />

& Performance entitled “Sentiment and Sentience: Black Performance<br />

Since Scenes of Subjection (March 2017). She is currently working on her<br />

book manuscript entitled Death’s Futurity: The Visual Culture of Death in<br />

Black Radical Politics. Aranke received her PhD in Performance Studies<br />

from the University of California, Davis.<br />

Melissa Gorman is a designer living and working in Brooklyn,<br />

NY. She has collaborated on numerous artist books and projects;<br />

including Olafur Eliasson: Your colour memory (Arcadia University Art<br />

Gallery, 2006), Taken With <strong>Time</strong> (The Print Center, 2006), and Sun<br />

Pictures and Other Broken Images, (The Print Center, 2008). Her design<br />

practice encompasses a wide range of projects, including visual identity,<br />

social impact design, and illustration. She received a BA from Bennington<br />

College and a Masters in Design from The School of Visual Arts, NY.<br />

Leah Kolb is Associate Curator at the Madison Museum of Contemporary<br />

Art. Recent curatorial projects include Claire Stigliani: Half-<br />

Sick of Shadows (2016) and Kim Schoen: Have You Never Let Someone Else<br />

Be Strong? (2015). With Dr. Richard Axsom, she worked on the travelling<br />

<strong>exhibition</strong> and <strong>catalog</strong>ue raisonné Frank Stella Prints: A Retrospective<br />

(2016); Axsom and Kolb are currently undertaking a <strong>catalog</strong>ue raisonné<br />

of Terry Winters’ prints and drawings. In partnership with artist Jason S.<br />

Yi, she co-founded Plum Blossom Initiative and its accompanying <strong>exhibition</strong><br />

program, Bridge Work, which aims to platform emerging artists and<br />

forge a more interconnected arts community throughout the Midwest.<br />

Gregory Volk is a New York based art critic and freelance<br />

curator, and associate professor in the School of the Arts at Virginia<br />

Commonwealth University. He writes regularly for Art in America, where<br />

he is a contributing editor, and his writings have appeared in many other<br />

publications, including Parkett and Sculpture. Among his contributions<br />

to <strong>exhibition</strong> <strong>catalog</strong>ues are essays on Bruce Nauman (Milwaukee Art<br />

Museum, 2006), Joan Jonas (Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona,<br />

2007), Ayse Erkmen (Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2011), and<br />

HiIdur Asgeirsdóttir Jónsson (Tang Teaching Museum/Reykjavik Art<br />

Museum, 2014).<br />

58 59

Artist’s Acknowledgements<br />

Queenspace<br />

The Pitch Project<br />

RISD Glass<br />

The Rauschenberg Residency<br />

UrbanGlass<br />

The Fam<br />

Special Thanks<br />

Anna <strong>Olujimi</strong><br />

Ann Brady<br />

April Rodmyre<br />

Audrey Yvette Washington<br />

Ben Wright<br />

Carrell Courtright<br />

Carrie Mae Weems<br />

Catherine Arline<br />

Courtney J. Martin<br />

Cybele Malone<br />

Denise Markonish<br />

Djelimory Diabate<br />

Dorie Guthrie<br />

Gari Lewis<br />

Hank Willis Thomas<br />

Isaac Saunders<br />

Jason S. Yi<br />

Jessica Todd<br />

Kelsey Mitchell<br />

Kerry James Marshall<br />

Lisa O’Sullivan<br />

Lori Hendricks<br />

Marjorie Levine<br />

Matt Hall<br />

Michael Levine<br />

Mike Brenner<br />

Sandra Jackson-Dumont<br />

Tim Finfrock<br />

Wardell Milan<br />

Madison Museum<br />

of Contemporary Art<br />

Board of Trustees<br />

May 2016 – April 2017<br />

Officers<br />

Rick Phelps, President<br />

Joe Alexander, Vice-President<br />

Jason Knutson, Vice-President<br />

Leslie Smith III, Vice-President<br />

Kathie Nichols, Secretary<br />

John Sylla, Treasurer<br />

Other Trustees<br />

Marian Bolz, Life Trustee<br />

Bryan Chan<br />

Karen Christianson<br />

Charlotte Cummins<br />

Tamara Dodge<br />

John Fritsch<br />

Sarah Guyer<br />

Cedric Johnson<br />

Valerie Kazamias, Chair, The Langer Society<br />

Elizabeth Kirchstein<br />

Oscar Mireles<br />

Bret Newcomb<br />

Margaret Pyle<br />

JoAnne Robbins<br />

John Ronzia<br />

Ellen Rosner<br />

Katheryn Howarth Ryan<br />

John Sims<br />

Sylvia Vaccaro<br />

Marc Vitale<br />

Kathleen Woit<br />

Jim Yehle, Past President<br />

Staff<br />

Nick Anderson, Gallery Attendant<br />

Richard Axsom, Senior Curator<br />

Jason Bank, Public Operations Supervisor<br />

Brian Bartlett, Technical Services Supervisor<br />

Mel Becker Solomon, Exhibitions Manager and Registrar<br />

Sheri Castelnuovo, Curator of Education<br />

Carol Chapin, Associate Registrar<br />

Gavin Christy, Gallery Attendant<br />

Christophe Delaunay, Curatorial Intern<br />

Simone Doing, Education Assistant<br />

Annik Dupaty, Director of Events and Volunteers<br />

Charlotte Easterling, Graphic Designer<br />

Aunna Escobedo-Wickham, Gallery Attendant<br />

Doug Fath, Preparator<br />

Stephen Fleischman, Director<br />

Leslie Genzler, Director of Retail Operations<br />

Connor Green, Technical Services Assistant<br />

Basha Harris, Gallery Attendant<br />

Tom Hasting, Public Operations Supervisor<br />

Ryan Holley, Gallery Attendant<br />

Stephanie Howard, Public Operations Supervisor<br />

Shelby Kahr, Gallery Attendant<br />

Jamie Kolar, Public Operations Supervisor<br />

Leah Kolb, Associate Curator<br />

Kaitlin Kropp, Associate Director of Member Engagement<br />

Janet Laube, Education Associate<br />

Erika Monroe-Kane, Director of Communications<br />

Dan Nergaugen, Gallery Attendant<br />

Alyssa O’Conner, Associate Preparator/Assistant Registrar<br />

Michael Paggie, Business Manager<br />

Sydney Prall, Gallery Attendant<br />

Judy Schwickerath, Accountant<br />

Emma Shore, Gallery Attendant<br />

Marilyn Sohi, Registrar, Permanent Collection<br />

Laurie Stacey, Store Manager<br />

Gabe Strader-Brown, Technical Services Assistant<br />

Bob Sylvester, Director of Public Operations<br />

Elizabeth Tucker, Director of Development<br />

Miles Verana, Gallery Attendant<br />

Tony Vincent, Gallery Attendant<br />

Kenneth Xiong, Public Operations Supervisor<br />

Stephanie Zech, Associate Registrar<br />

60 61

Exhibition Checklist<br />

Photography Credits<br />

All work courtesy the artist. Height precedes length.<br />

Unless noted below, all images ©<strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>.<br />

T-Minus Ø, 2017<br />

Installation of 13 mounted flags: digital print on cotton with aluminum pole,<br />

artist-made aluminum finial, and zinc pole mount<br />

Flag: 24 x 36 inches; pole: 73 x ½ x ½ inches; finial: ½ x ½ x ½ inches<br />

Ville Radieuse, habite-à-machine (The Radiant City, the living machine), 2017<br />

Installation: 25 sheets of digitally printed paper, wheat paste, and found objects<br />

132 x 120 inches<br />

The Black That Birthed Us, 2017<br />

Installation: 25 sheets of digitally printed paper, wheat paste, found photographs, vr goggles, and digital clocks<br />

132 x 120 inches<br />

The Drop, from the series InDecisive Moments, 2017<br />

Hand-blown glass and water<br />

12 x 7 ½ x 7 ½ inches<br />

Blue Ebb, from the series InDecisive Moments, 2017<br />

Hand-blown glass and water<br />

12 x 6 x 6 inches<br />

The Chase, from the series InDecisive Moments, 2017<br />

Hand-blown glass and water<br />

9 x 10 x 10 inches<br />

A Sheltered Wish, from the series InDecisive Moments, 2017<br />

Hand-blown glass and water<br />

22 x 6 ½ x 6 ½ inches<br />

Christmas Bus, from the series Killing <strong>Time</strong>, 2017<br />

Handcuffs and costume jewelry<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

Litmus Test, from the series Killing <strong>Time</strong>, 2017<br />

Handcuffs and costume jewelry<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

Never Adds Up, from the series Killing <strong>Time</strong>, 2017<br />

Handcuffs and costume jewelry<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

Stowaway, from the series Killing <strong>Time</strong>, 2017<br />

Handcuffs and costume jewelry<br />

15 x 6 inches<br />

Solitaire, from the series Killing <strong>Time</strong>, 2017<br />

Handcuffs and costume jewelry<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

Fathom, 2017<br />

Installation with 6 chandeliers, rubber inner tubes, wooden pallets<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

6–7 “United Nations Trusteeship Council Chamber in New York City” by MusikAnimal,<br />

via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0.<br />

8–9 “Earth Rise as Seen from Lunar Surface (5052124921)” by NASA/Apollo 11, via Wikimedia<br />

Commons, licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

12 Melvin Edwards, Some Bright Morning, 1963. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York.<br />

© 2017 Melvin Edwards/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.<br />

15 “New York City—United Nations Headquarters” by Norbert Nagel, via Wikimedia Commons,<br />

licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0.<br />

19 “8. Interior, Ornate <strong>Time</strong> Zone Clock, Lobby, First Floor - Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, Broad &<br />

Walnut Streets, Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, PA” by Historic American Buildings Survey,<br />

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS PA,51-PHILA,344—8, via Wikimedia<br />

Commons, licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

20–21 “Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion<br />

(1925)” by SiefkinDR, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed by CC-BY-SA 4.0.<br />

22 “Pruitt-Igoe, low angle oblique USGA photograph” by United States Geological Survey,<br />

via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

26–27 “The South Polar Trail” by Ernest Edward Mills Joyce from Biodiversity Heritage Library<br />

via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

35 Image by Mufid Majnun, via Pixabay, licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

36–37 “Orthophoto of Rikers Island” by U.S. Geological Survey, via Wikimedia Commons,<br />

licensed under CC0 Public Domain.<br />

38–39 Main Cell block, Dublin Prison by Tony Hisgett, via Wikimedia Commons,<br />

licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0.<br />

42 “Awaiting Rescue” by The National Archives UK, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed by<br />

Flickr’s The Commons.<br />

48 Frederic Edwin Church, Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860. The Cleveland Museum of Art.<br />

50–51, 58 Image ©Melissa Gorman.<br />

54 Image ©Mark Poucher.<br />

55 “Garuda Indonesia domestic and regional route” by Gunawan Kartapranata, via Wikimedia<br />

Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.<br />

56–57 “Pray / Salah in Masjid ul Harram” by Najamuddin Shahwani, via Wikimedia Commons,<br />

licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.<br />

59 “STS-128 EVA2 Christer Fuglesang” by NASA, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under<br />

CC0 Public Domain.<br />

65 “Hindu public prayer in Haridwar” by Flickr.com user “lazyoldsun,” via Wikimedia Commons,<br />

licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.<br />

62 63

MADISON MUSEUM of<br />

CONTEMPORARY ART<br />

<strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> is a publication of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA),<br />

created in conjunction with the <strong>exhibition</strong> <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> (May 6–August 13, 2017).<br />

227 State Street<br />

Madison, WI 53703<br />

Copyright © 2017 Madison Museum of Contemporary Art<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any<br />

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or information storage or retrieval<br />

system, without the permission in writing from the publisher.<br />

ISBN: 978-0-913883-38-9<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data<br />

Names: Aranke, Sampada. | Volk, Gregory. | Kolb, Leah. | Madison Museum of<br />

Contemporary Art (Madison, Wis.) organizer, host institution.<br />

Title: <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong> : <strong>Zulu</strong> time / essays by Sampada Aranke, Gregory Volk,<br />

and Leah Kolb.<br />

Description: Madison : Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017. | “<strong>Kambui</strong><br />

<strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> is a publication of the Madison Museum of Contemporary<br />

Art (MMoCA), created in conjunction with the <strong>exhibition</strong> <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>:<br />

<strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> (May 6-August 13, 2017).” | Includes bibliographical references.<br />

Identifiers: LCCN 2017016950 | ISBN 9780913883389 (pbk.)<br />

Subjects: LCSH: <strong>Olujimi</strong>, <strong>Kambui</strong>--Exhibitions.<br />

Classification: LCC N6537.O48 A4 2017 | DDC 709.2--dc23<br />

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017016950<br />

Catalogue design:<br />

Melissa Gorman, New York<br />

Manuscript Editor:<br />

Katie Kazan, Madison, WI<br />

Project Coordinator:<br />

Leah Kolb<br />

The <strong>exhibition</strong> and the publication <strong>Kambui</strong> <strong>Olujimi</strong>: <strong>Zulu</strong> <strong>Time</strong> were made possible with generous funds<br />

from The DeAtley Family Foundation; MillerCoors; Terry Family Foundation; WhiteFish Partners LLC;<br />

a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and National Endowment<br />

for the Arts; and MMoCA Volunteers.<br />

Printed by Bookmobile Craft Digital, Minneapolis, in an edition of 1000.<br />

In stated dimensions, height precedes width precedes depth.<br />

All images courtesy of the artist.