You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Japanese Poetry<br />

Presented by<br />

Maqsood Hasni<br />

Free Abuzar Barqi Kutab’khana<br />

Aug. 2017<br />

1

History of Japanese Poetry<br />

The classical Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> is referred as waka.<br />

Man’yoshu, dating back to the middle of 7th century, is<br />

the oldest book of Japanese <strong>poetry</strong>. Man’yoshu contains<br />

20 volumes of waka. The authors of most of these poems<br />

2

3<br />

are unknown, but they ranged from aristocrats to the<br />

general public, women as well as eminent poets of the<br />

time such as Nukata no Okimi and Kakinomoto Hitomaro.<br />

During the period of Chinese influence, Chinese poets<br />

recited poems in the courts of the Japanese royals and<br />

the aristocrats. Japanese poets even went to China to<br />

study <strong>poetry</strong>. Poetry tradition was so much ingrained in<br />

Japanese culture that waka (<strong>poetry</strong>) was used to write<br />

letters and community.<br />

During the Heian period (794 and 1185), Japanese royals<br />

and aristocrats organized waka recitation contest.<br />

Notable works in this period is Wakan Roeishu, which<br />

was compiled by Fujiwara no Kinto, Tale of Genji by<br />

Poetess Murasaki Shikibu, and The Pillow Book, whose<br />

author is unknown.<br />

In the 12th century, new <strong>poetry</strong> forms Imayo and Renga<br />

developed. Recitation of Imayo was accompanied with<br />

music and dance, and Renga was written in a

communication form between two people.<br />

Haikai (also called Renku) developed during the Edo<br />

period (1602–1869). Matsuo Basho was the great haikai<br />

poet of this era. He also developed haibun, a <strong>poetry</strong> style<br />

that combined haiku with prose. During Edo period, poets<br />

collaborated with painters and blended <strong>poetry</strong> with<br />

paintings, which gave birth to new visual <strong>poetry</strong> form<br />

called haiga. Notable amongst poet-painters is Yosa<br />

Buson. He wrote haiku poems in his paintings. Senryu, a<br />

satirical poem in haikai form, developed in the late Edo<br />

period.<br />

By the 19th century, major Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> forms were<br />

already developed. With the Western influence, freeform<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> style developed in Japan. This <strong>poetry</strong> style was<br />

called Jiyu-shi, literally freestyle <strong>poetry</strong>, or Shintai-shi,<br />

new form <strong>poetry</strong>. Shi is the Japanese word for Chinese<br />

<strong>poetry</strong>, but today it is used for modern Japanese <strong>poetry</strong><br />

style.<br />

4

5<br />

Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku<br />

Poets on the Verge of Death Japanese Death Poems:<br />

Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of<br />

Death<br />

Waka<br />

Japan was heavily influenced by Chinese <strong>poetry</strong>;<br />

Japanese poets composed poems in Chinese language.<br />

The Japanese poems following the classical Chinese<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> are called kanshi. Classical Japanese poets also<br />

wrote <strong>poetry</strong> in Japanese language. All the poems<br />

written in Japanese language were referred as waka.<br />

Waka is a Japanese word for <strong>poetry</strong>. The Kokin-shu<br />

(905) Man’yoshu (7th century) are two books of<br />

Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> that contain waka in different patterns.<br />

Man’yoshu, which as 20 volumes, contain waka of<br />

different forms such as tanka (short poem), choka (long<br />

poem), bussokusekika (Buddha footprint poem), sedoka<br />

(repeating-the-first-part poem) and katauta (half poem).

By the time Kokin-shu was compiled, most of these<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> forms, except tanka, had vanished. Therefore,<br />

waka was used to refer tanka <strong>poetry</strong>. Tanka also gave<br />

birth to renga and haiku. Choka and sedoka are early<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> forms whereas renga, haikai, and haiku are later<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> forms.<br />

Waka: The Classical Japanese Poetry Forms<br />

Poetry Forms<br />

Pattern<br />

Meaning<br />

Katauta<br />

5,7,7<br />

Half Poem<br />

Tanka<br />

5,7,5,7,7<br />

6<br />

Short Poem

7<br />

Choka<br />

5,7,5,7,5,7,5,7,7<br />

Long Poem<br />

Bussokusekika<br />

5,7,5,7,7,7<br />

Buddha Footprint Poem<br />

Sedoka<br />

5,7,7,5,7,7<br />

Repeating-the-First-Part Poem<br />

Haikai<br />

When renga is composed in humorous and comic themes,<br />

it is called haikai. Haikai is referred as mushin renga or<br />

comic renga. Haikai <strong>poetry</strong>, sometimes also called hokku,<br />

is composed in three lines with nature and season as the<br />

dominant theme. Hokku or haikai <strong>poetry</strong> form gained<br />

prominence in the 17th century. Matsuo Basho

(1644-1694) was one of the early poets to perfect the art<br />

of hokku/haikai <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

8<br />

Renga<br />

Renga is a linked-verse Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> from composed<br />

in tanka pattern. Renga was originally composed by two<br />

or more poets. Renga developed when poets tried to<br />

communicate through <strong>poetry</strong>. The first three lines of<br />

renga, in 5-7-5 syllables format, were composed by a<br />

poet and the remaining 7-7 syllables were composed by<br />

another. In ancient Japan, composing renga was a<br />

favorite pastime affairs of poets, aristocrats, even<br />

general public. The earliest record of renga poems is<br />

found in Kin'yo-shu, an anthology of poems compiled in<br />

about 1125.<br />

In the beginning, renga were based on light topic,<br />

however, by 15th century, there was a distinction drawn<br />

between ushin renga (serious renga) and mushin renga<br />

(comic renga).

Renga <strong>poetry</strong> contains at least 100 verses. The first<br />

stanza (the first three lines), of renga is called hokku.<br />

Hokku of a renga later developed into haiku <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

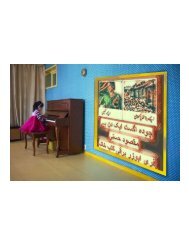

A little cuckoo across a hydrangea, a haiga by Yosa<br />

Buson (1716 - 1784)<br />

A little cuckoo across a hydrangea, a haiga by Yosa<br />

Buson (1716 - 1784) | Source<br />

When the Japanese poets composed haiku and senryu,<br />

they used words in terms of sound effect. This was not<br />

possible when these Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> forms were<br />

adapted in other languages. The 5-7-5 pattern called<br />

kana (17 kana in total) in Japanese language was<br />

translated as 17 syllables in 5-7-5 format. Haiku<br />

were/are also written in 3-5-7, 3-5-3 and 5-8-5<br />

pattern.<br />

Today haiku are mostly written in three lines, in 17 or<br />

less syllables.<br />

9

10<br />

Haiku is not a sentence in three fragments.<br />

The best haiku are open ended.<br />

Haiku is about nature and season as experienced or<br />

observed by the poet.<br />

Haiku uses minimal punctuation.<br />

Metaphors, similes and other <strong>poetry</strong> elements are<br />

unnecessary in haiku.<br />

Haiku does not tell but shows the emotions as<br />

experienced by the poet.<br />

Haiku present specific moments rather than extensive<br />

picture.<br />

Haiku, senryu, haiga and tanka are used in both, singular<br />

as well as plural form.<br />

Haiku<br />

The word haiku combines two different words haikai and<br />

hokku. Haikai is a linked-verse Japanese poem in renga

<strong>poetry</strong> style and hokku is the name given to the first<br />

stanza of renga <strong>poetry</strong>. Haikai, a type of renga <strong>poetry</strong>,<br />

consists of at least 100 verses in 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.<br />

Haiku <strong>poetry</strong> form developed from hokku of haikai and<br />

became an independent <strong>poetry</strong> form in the 17th century;<br />

however, the word haiku was not used until 19th century.<br />

Haiku was named by Japanese poet Masaoka Shik.<br />

Haiku is non-rhyming Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> form. It is<br />

composed in three lines, in 5-7-5 format, 17 syllables in<br />

total. Haiku is about nature and plays with the imagery,<br />

metaphors and emotions of seasons.<br />

Japanese characters were developed from Chinese and<br />

Korean alphabets, which are basically pictograms. The<br />

style of haiku was perfectly compatible with the language<br />

because a single character could say many things.<br />

However, in other language such as English, an alphabet<br />

is just a letter that cannot evoke feelings and emotions,<br />

or even sensible meaning. Therefore, when haiku entered<br />

11

into English and other languages, there were few<br />

modifications. The three lines form was maintained in<br />

haiku, but the strictness of 17 syllables could not always<br />

be retained.<br />

The modern haiku does not strictly follow 17 syllables in<br />

5-7-5 format. Some haiku poets follow 5-3-5 format,<br />

whereas some do not even follow the uniform pattern of<br />

syllables. The most common haiku format is unrhymed<br />

three lines <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

12<br />

Haiku <strong>poetry</strong> form was incorporated in the Western<br />

languages in the 19th century. Imagists popularized<br />

English haiku <strong>poetry</strong> in the early 20th century.<br />

Haiku Poetry<br />

Haiku: Rose<br />

Haiku about rose. Pictures of rose.<br />

Haiku: Nature<br />

Haiku were originally written about nature. Two haiku

13<br />

about nature and a video based on haiku about nature<br />

Senryu<br />

In the 18th century, Karai Senryu (1718-1790) composed<br />

short non-rhyming poems, about human foibles and<br />

ironies, in 5-7-5 form. His poems were called Senryu.<br />

Later, all the poems that followed the tradition of Karai<br />

Senryu were called senryu. Karai Senryu is the pen<br />

name of Karai Hachiemon.<br />

Senryu – a Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> form composed in 17<br />

syllables, in 5-7-5 format – is similar to haiku. Like haiku,<br />

there have been some modifications in senryu pattern, in<br />

modern times. The basic difference between haiku and<br />

senryu is, haiku is written about season and nature,<br />

whereas senryu is about the ironies of life. Sometimes it<br />

is hard to differentiate senryu with haiku because<br />

senryu can also be a commentary on nature or season.<br />

To differentiate a senryu with haiku you have to consider<br />

the tone. Thematic treatment in haiku is serious whereas

senryu are humorous or cynical.<br />

Normally, senryu presents setting, subject and action. It<br />

is a commentary on human nature in satirical or<br />

humorous tone.<br />

Haiga by Vinaya<br />

Haiga by Vinaya<br />

Haiga<br />

Haiga: Love<br />

Haiga about carnal, ethereal and motherly love. Tips on<br />

how to create Haiga.<br />

Haiga<br />

Haiga (hai=poem/haiku; ga=painting) is a visual <strong>poetry</strong><br />

form, which originated in China in the 7th century, and<br />

was perfected in Japan the 17th century. Painting, <strong>poetry</strong><br />

and calligraphy were called ‘Three Perfections’ in<br />

ancient China. The Three Perfections was first practiced<br />

14

during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The Three<br />

Perfections of Tang Dynasty heavily influenced Japanese<br />

art and literature.<br />

Calligraphy, the art of handwriting, was highly regarded<br />

in ancient China. Artists wrote deep and profound lines,<br />

in beautiful script, over the painting. Japanese artists<br />

emulated the tradition of writing beautiful lines over a<br />

painting. Painting and <strong>poetry</strong> became complimentary art<br />

forms. Poets with painting ability, or the painters who<br />

were poets, created visual <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

During the Edo period (1602–1869) haiku and senryu<br />

were combined with painting and calligraphy. Thus, a new<br />

visual <strong>poetry</strong> form was born, it was called Haiga. Haiga is<br />

a haiku/senryu poem written over a painting or<br />

photograph.<br />

15<br />

Haiga is a <strong>poetry</strong> blended with picture that tells about<br />

profound observation of life, living and the world.<br />

Thematically the <strong>poetry</strong> in the haiga is similar to the

picture. Haiga was initially painted over wooden blocks,<br />

stones, cloths, and paper and used as room decoration.<br />

Haiga is highly regarded in Zen Buddhism. Creating haiga<br />

is thought to be a type of Buddhist meditation.<br />

16<br />

Modern haiga poet/artist combines haiku/senryu with<br />

digital pictures. The modern haiga normally presents a<br />

haiku or senryu written on painting or photograph.<br />

Given a choice between different Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> forms,<br />

what do you choose?<br />

Haiku<br />

Senryu<br />

Haiga<br />

Tanka<br />

See results<br />

Tanka<br />

In the beginning, when Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> forms were not

developed, waka was used to denote all kinds of poem.<br />

Waka literally means classical Japanese <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

Man’yoshu, which dates back to the middle of 7th<br />

century, is the oldest book of Japanese <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

Man’yoshu contains long and short poems. Man’yoshu<br />

categorizes short poems as waka and long poems as<br />

choka. The word waka was later replaced with tanka.<br />

Tanka is the modern name for waka. It is one of the<br />

oldest Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> styles.<br />

Tanka is non-rhyming Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> form composed<br />

in five lines, in 5-7-5-7-7 format, 31 syllables in total. It<br />

consists of two elements. The first three lines (5-7-5) is<br />

called kami-no-ku (literally upper phrase) and the last<br />

two lines (7-7) is called shimo-no-ku (literally lower<br />

phrase).<br />

In the ninth and tenth centuries, short poems dominated<br />

Japanese <strong>poetry</strong> styles. Kokinshu is one of the earliest<br />

collections of tanka. However, tanka <strong>poetry</strong> form was<br />

17

18<br />

almost lost for one thousand years. Japanese poet,<br />

essayist, and critic Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) is<br />

credited for the revival of tanka <strong>poetry</strong>, and the<br />

invention of haiku from hokku (haikai). Masaoka lived<br />

during the reign of Japanese emperor Meiji Tenno<br />

(1852-1912). Meiji is credited for the development of<br />

modern Japan. Masaoka tried to do the same thing in<br />

Japanese <strong>poetry</strong>.<br />

Kokin-shu, an anthology of <strong>poetry</strong>, was compiled by a<br />

court noble Ki Tsurayuki in 905. Kokin-shu styles of<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> ruled Japan for about one thousand years.<br />

However, Masaoka praised the <strong>poetry</strong> styles in<br />

Man’yoshu (7th century) and degraded Kokin-shu.<br />

Man’yoshu contains long and short <strong>poetry</strong> forms. Tanka<br />

is a short <strong>poetry</strong> form in Man’yoshu.<br />

The modern tanka <strong>poetry</strong> form was revived in the late<br />

1980s by Japanese poetess Tawara Machi.<br />

Tanka: Poems for Kids - and adults

If a haiku is usually (mistakenly) thought of as a 3-line,<br />

5-7-5 syllable poem, then the tanka would be a 5-line,<br />

5-7-5-7-7 syllable poem. However, as with haiku, it’s<br />

better to think of a tanka as a 5-line poem with 3 short<br />

lines (lines 2, 4, 5) and 2 very short lines (lines 1 and 3).<br />

While imagery is still important in tanka, the form is a<br />

little more conversational than haiku at times. It also<br />

allows for the use of poetic devices such as metaphor<br />

and personification (2 big haiku no-no’s).<br />

Like haiku, tanka is a Japanese poetic form.<br />

*****<br />

19

While I’m sure there are problems with my attempt, here<br />

is my tanka attempt, which you can use as an example of<br />

the form:<br />

Chopin’s waltzes<br />

turn circles in my head<br />

for hours<br />

as I think of her hand<br />

turning the world inside out<br />

Somonka: Poetic Forms<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | October 17, 2013<br />

1<br />

The somonka is a Japanese form. In fact, it’s basically<br />

two tankas written as two love letters to each other (one<br />

tanka per love letter). This form usually demands two<br />

authors, but it is possible to have a poet take on two<br />

personas. .<br />

Here’s an example somonka:<br />

“Sugar,” by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

20

I’m waiting to die;<br />

I think it will happen soon–<br />

this morning, I saw<br />

two bright hummingbirds battling<br />

over some sugar water.<br />

I know; I was there.<br />

I chased after them for you<br />

until thirst stopped me.<br />

Fetch me some water. I have<br />

a little sugar for you.<br />

*****<br />

Get your <strong>poetry</strong> published.<br />

*****<br />

Senryu<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | May 23, 2013<br />

0<br />

It’s been two months since our last poetic form challenge<br />

and the April PAD Challenge is over, so let’s get another<br />

one started.<br />

21

This time around, the challenge is to write senryu, which<br />

is a variation of the haiku. As with haiku, senryu are most<br />

often 3-line poems containing 17 (or fewer)<br />

syllables–often in a 5-7-5 pattern. Senryu does not<br />

include a cutting or seasonal word, and it’s usually about<br />

human issues (not nature, as is the case with haiku).<br />

In fact, many people write poems that they call haiku that<br />

are really senryu. So in a way, it’s a form of <strong>poetry</strong> that<br />

is often suffering from identity theft and mistaken<br />

identity.<br />

OK, so that’s the form.<br />

Here are the guidelines for competing in this challenge:<br />

Write and share original and previously unpublished<br />

senryu in the comments below (on this specific<br />

post).<br />

<br />

Deadline for entries: May 31, 11:59 p.m. (Atlanta,<br />

Georgia time).<br />

<br />

No entry fee.<br />

22

Include your name as you would like it to appear in<br />

print (just in case you’re chosen as a winner).<br />

Speaking of winners, the top senryu (and maybe a<br />

few extra, since the form is so short) will be<br />

published in a future issue of Writer’s Digest<br />

magazine in the Poetic Asides Inkwell column.<br />

Anyone and everyone (from any location on the<br />

globe) is encouraged to participate. It’s free and fun.<br />

Note to new poets: You’ll have to register on the site<br />

(don’t worry; it’s free) to comment. And for your<br />

first few comments, you may have to wait for one of<br />

us editors to approve your comment. Don’t worry;<br />

we’ll get to you–and then, after that first approval,<br />

you should be good to go into the future.<br />

Good luck!<br />

Katauta Poems<br />

The katauta is a Japanese poetic form that is actually<br />

considered an incomplete or half-poem. It’s a 3-liner that<br />

follows either 5-7-5 or more commonly 5-7-7 syllables<br />

23

per line. Sounds like a haiku or senryu, right? But this<br />

poem is specifically addressed to a lover.<br />

When paired together, multiple katautas act as a<br />

question and answer conversation between lovers to<br />

form sedoka. If the concept of sedoka sounds familiar,<br />

it’s similar to somonka, in which 2 tankas are written as<br />

love letters.<br />

*****<br />

Here’s my attempt at a Katauta:<br />

Untitled Katauta, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

Why do winter stars<br />

shine brighter than summer stars<br />

as if they are shards of glass?<br />

And while we’re at it, here’s a Sedoka:<br />

Untitled Sedoka, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

why do winter stars<br />

shine brighter than summer stars<br />

as if they are shards of glass?<br />

24

don’t blame the seasons<br />

on the ever changing heat<br />

of your lover’s quick embrace.<br />

*****<br />

Dodoitsu: Poetic Forms<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | July 14, 2015<br />

0<br />

Ready to learn a new poetic form? And yeah, you know<br />

that a new WD Poetic Form Challenge is just around the<br />

corner.<br />

The dodoitsu is a Japanese poetic form developed<br />

towards the end of the Edo Period, which came to an end<br />

in 1868. As with most Japanese forms, the dodoitsu does<br />

not have meter or rhyme constraints, focusing on<br />

syllables instead.<br />

This 4-line poem has seven syllables in the first three<br />

lines and five syllables in the fourth–and final–line. The<br />

dodoitsu often focuses on love or work with a comical<br />

twist. While my examples below do not have titles, I<br />

25

haven’t found any word on whether dodoitsu traditionally<br />

have titles or not.<br />

*****<br />

Here is an example focused on work:<br />

when a geologist speaks<br />

& the earth trembles seven<br />

meteorologists get<br />

sucked in a twister<br />

Here is an example focused on love:<br />

i gave her all my heart &<br />

heartache but she returned it<br />

with the admission they gave<br />

her severe heartburn<br />

*****<br />

Mondo: Poetic Form<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | February 27, 2017<br />

0<br />

26

Some folks may remember me covering katauta (and<br />

sedoka) poems last December. Today’s poetic form<br />

mondo is a close relative of those forms.<br />

Mondo Poems<br />

Mondo poems are often very brief collaborative affairs<br />

that present a question and answer in the style of trying<br />

to glean meaning from nature. Mondos can be as short<br />

as a one-liner or as long as two 5-7-7 syllable stanzas<br />

(the first stanza presenting the question; the second the<br />

answer). Examples below.<br />

*****<br />

Here’s my attempt at a one-line Mondo:<br />

Untitled, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

why do winter stars shine brighter? i can’t hear them<br />

laugh.<br />

And here’s a two-stanza Mondo:<br />

Untitled, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

27

why do winter stars<br />

shine brighter than summer stars<br />

and why do i notice them?<br />

i can’t hear them laugh,<br />

but i remember the way<br />

they once entered the darkness.<br />

*****<br />

If mondo seems a little too much like sedoka, I totally<br />

understand. I think the main difference is a focus on<br />

nature and trying to attain a zen-like meaning from<br />

natural source material.<br />

*****<br />

Katauta: Poetic Form<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | December 19, 2016<br />

1<br />

Let’s look at one or two more poetic forms before the<br />

end of the year, starting with the katauta poem.<br />

28

Katauta Poems<br />

The katauta is a Japanese poetic form that is actually<br />

considered an incomplete or half-poem. It’s a 3-liner that<br />

follows either 5-7-5 or more commonly 5-7-7 syllables<br />

per line. Sounds like a haiku or senryu, right? But this<br />

poem is specifically addressed to a lover.<br />

When paired together, multiple katautas act as a<br />

question and answer conversation between lovers to<br />

form sedoka. If the concept of sedoka sounds familiar,<br />

it’s similar to somonka, in which 2 tankas are written as<br />

love letters.<br />

*****<br />

Here’s my attempt at a Katauta:<br />

Untitled Katauta, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

why do winter stars<br />

shine brighter than summer stars<br />

as if they are shards of glass?<br />

And while we’re at it, here’s a Sedoka:<br />

Untitled Sedoka, by Robert Lee Brewer<br />

29

why do winter stars<br />

shine brighter than summer stars<br />

as if they are shards of glass?<br />

don’t blame the seasons<br />

on the ever changing heat<br />

of your lover’s quick embrace.<br />

*****<br />

Gogyohka: Poetic Form<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | October 20, 2014<br />

0<br />

If only a poetic form existed that could be both concise<br />

and free. Oh wait a second, there’s gogyohka!<br />

Gogyohka was a form developed by Enta Kusakabe in<br />

Japan and translates literally to “five-line poem.” An<br />

off-shoot of the tanka form, the gogyohka has very<br />

simple rules: The poem is comprised of five lines with<br />

one phrase per line. That’s it.<br />

*****<br />

30

What constitutes a phrase in gogyohka?<br />

From the examples I’ve seen of the form, the definition of<br />

phrase is in the eye of the beholder. A compound or<br />

complex sentence is probably too long, but I’ve seen<br />

phrases as short as one word and others more than five<br />

words.<br />

So it’s a little loose, which is kind of the theory behind<br />

gogyohka. It’s meant to be concise (five lines) but free<br />

(variable line length with each phrase). No special<br />

seasonal or cutting words. No subject matter<br />

constraints. Just five lines of poetic phrases.<br />

Here’s my attempt at a Gogyohka:<br />

“Halloween”<br />

Ghosts hang<br />

from the willow<br />

as the children run<br />

from one door<br />

to the next.<br />

*****<br />

31

32<br />

Haibun Poems: Poetic Form<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | September 3, 2012<br />

0<br />

The haibun is the combination of two poems: a prose<br />

poem and haiku. The form was popularized by the 17th<br />

century Japanese poet Matsuo Basho. Both the prose<br />

poem and haiku typically communicate with each other,<br />

though poets employ different strategies for this<br />

communication—some doing so subtly, while others are<br />

more direct.<br />

The prose poem usually describes a scene or moment in<br />

an objective manner. In other words, the pronoun “I”<br />

isn’t often used—if at all. Meanwhile, the haiku follows the<br />

typical rules for haiku.<br />

Here is my attempt at a haibun poem:<br />

“1985”<br />

In the shadow of the Nevado del Ruiz, rice farmers woke<br />

as if on any other morning. Their daily pleasures and

worries were the same as always. Even the smoke and<br />

eruptions that afternoon were familiar—though masked<br />

by a thunderstorm—no one aware of the approaching<br />

lahars.<br />

not the sound<br />

but drops of rain<br />

scatter ants<br />

*****<br />

As you may have guessed, a new poetic form challenge is<br />

around the corner. It’d probably be a good idea to work<br />

on your haibuns today and share them tomorrow.<br />

*****<br />

Haiku Revisited<br />

By: Robert Lee Brewer | August 8, 2007<br />

0<br />

Michael Dylan Welch, who wrote on haiku for the 2005<br />

Poet’s Market, stopped by and offered some great advice<br />

in the comments to my “Haiku: Easy or Hard?” post from<br />

earlier this week. While it’s probably best to read the<br />

33

comments first-hand, I figured I’d make it easy on people<br />

since the advice is very useful.<br />

Some highlights:<br />

<br />

“My sense of things is that practically no current<br />

literary haiku writers believe the 5-7-5 pattern of<br />

syllables is applicable in English (in Japanese they<br />

count sounds, not syllables, which is why a<br />

one-syllable word like ‘scarf,’ in English, is counted<br />

as FOUR sounds when said in Japan, something like<br />

‘su-ka-ar-fu’), so I’m not sure I’d call 5-7-5 a<br />

‘traditional’ viewpoint in English. More like a<br />

traditional misunderstanding.”<br />

“Rather, what matters most in the tradition of haiku<br />

is kigo (season word) and kireji (cutting word), as<br />

well as objective sensory imagery (thus one<br />

wouldn’t say that rain ‘stampedes’ the mud, because,<br />

as interesting as that is, it shows your<br />

interpretation and lacks the objectivity that lets<br />

readers have their own reaction to a carefully<br />

crafted image).”<br />

34

35<br />

“At any rate, I always like to quote philosopher<br />

Roland Barthes on haiku. He said that ‘The haiku has<br />

this rather fantasmagorical property: that we<br />

always suppose we ourselves can write such things<br />

easily.’ Paradoxically, haiku is both easy and hard.”<br />

Welch also provided to links to check out:<br />

1. His essay “Becoming a Haiku Poet” at<br />

http://www.haikuworld.org/begin/mdwelch.apr200<br />

3.html<br />

2. Keiko Imaoka’s essay “Forms in English Haiku” at<br />

http://asgp.org/agd-poems/keiko-essay.html<br />

I would like to thank Welch, who is an expert in his field,<br />

for sharing so much great information with everyone.<br />

This is what having a community of poets is all about as<br />

far as I’m concerned.<br />

Haiku, Senryu, Haiga and Tanka<br />

The Chinese contribution in the development of Japanese<br />

script and literature is immense. Even though the history<br />

of Japanese literature goes beyond 7th century AD,<br />

much of the Japanese literature took inspiration from

Chinese literature during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in<br />

China.<br />

Kojiki (712) and Nihonshoki (720) are the earliest<br />

records of Japanese literature. Kojiki and Nihonshoki are<br />

the books of Japanese mythology, history and poems.<br />

Mythology and history in these books were recorded<br />

from the oral tradition by Hieda no Are and credited to<br />

Yasumaro. The poems in these books are said to be<br />

composed by Japanese God Susanoo.<br />

In the beginning, Japanese poets used Chinese language<br />

to express their emotions, observations and insights.<br />

After the hundred years of writing in foreign language<br />

and form, Japanese poets developed a native style, which<br />

became integral to Japanese culture.<br />

36<br />

This one of the hundred prints illustrating the Japanese<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> anthology called the Hyakunin isshu, which was<br />

compiled by the poet Fuhiwara Teika 1162-1241<br />

This one of the hundred prints illustrating the Japanese

37<br />

<strong>poetry</strong> antology called the Hyakunin isshu, which was<br />

compiled by the poet Fuhiwara Teika 1162-1241 | Source

38

39