BMF SHOSTAKOVICH Program04

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

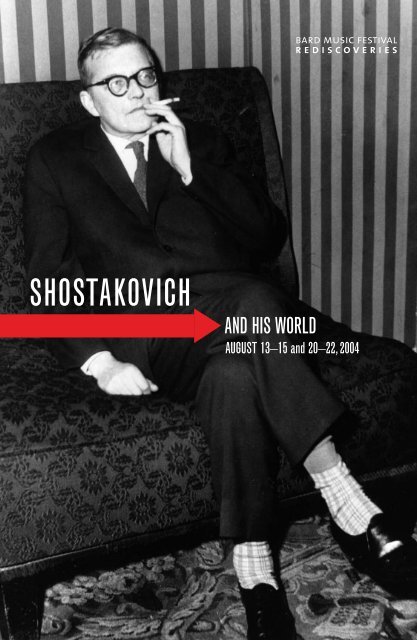

ard music festival<br />

rediscoveries<br />

<strong>SHOSTAKOVICH</strong><br />

AND HIS WORLD<br />

AUGUST 13–15 and 20–22, 2004

<strong>SHOSTAKOVICH</strong><br />

AND HIS WORLD<br />

AUGUST 13–15 and 20–22, 2004<br />

Leon Botstein, Christopher H. Gibbs,<br />

and Robert Martin, Artistic Directors<br />

Laurel E. Fay, Scholar-in-Residence 2004<br />

Please make certain the electronic signal on your<br />

watch, pager, or cellular phone is switched off<br />

during performance.<br />

The taking of photographs and the use of<br />

recording equipment are not allowed.

<strong>SHOSTAKOVICH</strong><br />

AS MAN AND MYTH<br />

Throughout his life, Dmitrii Shostakovich explored the theme of the creative<br />

artist versus his critics, satirizing and lamenting the misunderstanding, deprecation,<br />

and torture that are too often the lot of the artist. It was a subject he<br />

came to understand intimately from his own bitter experience. Shostakovich<br />

was to become the showcase victim of the most capricious and merciless critic<br />

of all, Joseph Stalin. Unwittingly, Shostakovich became an enduring symbol—a<br />

myth vital to both his countrymen and to the entire world—of the perilous<br />

position of the creative artist in a totalitarian society.<br />

In an era when perceptions of the moral integrity, political convictions, and, yes,<br />

sexual orientation of creative artists are brought increasingly to bear on the<br />

interpretation of the works they create, Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

remains a case apart. He was never simply a composer. Alternately lionized and<br />

vilified at Stalin’s cruel whim, Shostakovich was resilient. He was a survivor.<br />

Most important, he demonstrated—a relentless muse and his consummate<br />

professionalism goaded him to show—that art, in his case the ineffably resonant<br />

art of music, could withstand the most inhuman demands and abuses of<br />

repressive regimes. Shostakovich was an inspiration, a cultural icon, a symbol.<br />

Exactly what he symbolized has changed with the times. There has been as<br />

much argument about how his countrymen perceived his career and musical<br />

accomplishments at different periods as there has been among his avid<br />

Western following, especially regarding his complicity (or lack thereof) with<br />

the system that oppressed him. Now, with the triumph of the capitalist ideal<br />

over communism and the demise of the Soviet Union, the reevaluation of<br />

Shostakovich—myth and music—is being tackled with new intensity, even<br />

though the rhetoric, for the most part, is still loaded with political and moral<br />

subtexts scarcely less manipulative than those in play during the Cold War.<br />

What remains unquestioned and, indeed, what has only increased with the<br />

passage of time, is the appreciation of the singular vitality and relevance of<br />

his music.<br />

For many, the author of the Fifth, Seventh (Leningrad), Tenth, and Thirteenth<br />

(Babi Yar) symphonies is an artist who felt the suffering of his people deeply,<br />

who courageously challenged the prohibitive aesthetic restrictions of his<br />

time, to communicate through his music an emotional reality that could not<br />

be expressed any other way. For others, who isolate his patriotic cantatas and<br />

film music, as well as the voluminous number of official speeches and articles<br />

published over his name, Shostakovich betrayed his moral responsibility; as<br />

a lavishly decorated and honored “court” composer, he secured his survival<br />

and his individual artistic license only by collaborating with the system that<br />

repressed him.<br />

In the West, Shostakovich has been made the subject of at least three fictional<br />

portraits: a play (Master Class by David Pownall), a music-theater piece (Black<br />

Sea Follies by Stanley Silverman and Paul Schmidt), and a movie (Testimony,<br />

produced and directed by Tony Palmer, based on the controversial book of<br />

the same title—the “memoirs” as related to and edited by Solomon Volkov).<br />

Needless to say, these glimpses contrast sharply with the pious Soviet<br />

hagiographies, which as a matter of course distorted or suppressed inconvenient<br />

or unpalatable facts.<br />

In reality, of course, Shostakovich was a human being—an enormously gifted<br />

composer, but a complex human being with all the frailties and contradictions<br />

of his less exalted peers. He was not a martyr. Seemingly modest for a man of<br />

his unqualified talent, he could not have anticipated such an undeserved fate.<br />

Obliged for most of his life to walk a tightrope blindfolded without a safety net,<br />

his decisions and errors were understandably human.<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich was an unlikely candidate for mythology. Physically frail<br />

from his youth, shy, awkward with words, he was always most comfortable with<br />

music. Those who knew him best—and few of those survived the Stalin years—<br />

paint a picture of a very private person who did not open up readily to others.<br />

He had a mischievous sense of humor, an adventurous spirit, and the courage<br />

to stand up and fight for his aesthetic convictions when necessary. He was<br />

interested in a wide range of music, not excluding popular styles, and in his<br />

youth worked more actively in theater and film than in the symphonic medium.<br />

4<br />

5

It was the versatility of his talent, his interest in exploring new horizons and<br />

reaching new audiences, that helped secure his early reputation.<br />

In December 1931, Shostakovich gave an interview to Rose Lee of the New York<br />

Times. He maintained confidently that “there can be no music without an ideology.<br />

The old composers, whether they knew it or not, were upholding a political<br />

theory....We,as revolutionists, have a different conception of music. Lenin<br />

himself said that ‘music is a means of unifying broad masses of people.’ ...Not<br />

that Soviets are always joyous, or supposed to be. But good music lifts and<br />

heartens and lightens people for work and effort. It may be tragic but it must<br />

be strong. It is no longer an end in itself, but a vital weapon in the struggle.<br />

Because of this, Soviet music will probably develop along different lines from<br />

any the world has ever known. There must be a change!”<br />

There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of Shostakovich’s political or aesthetic<br />

convictions at the time. He was not an elitist composer. He was a patriot with a<br />

deep commitment to his people and culture. Along with a number of other<br />

artists, including the theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold and the film director<br />

Sergey Eisenstein, he was endeavoring to create a progressive new art necessary<br />

and appropriate to the new socialist reality. That art did not exclude overt propaganda;<br />

for the climaxes of his Second (Dedication to October) and Third (The<br />

First of May) symphonies, for instance, Shostakovich used a chorus to deliver<br />

stirring idealistic texts.<br />

Not all his attempts met with success, but Shostakovich did not abandon his<br />

efforts or limit his horizons. A song from his 1932 score to the film Counterplan<br />

became an instant hit; during World War II, with a new text by Harold Rome, it<br />

became a rallying anthem for the Allied nations. When his second opera, Lady<br />

Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, reached the stage in 1934, it played for two<br />

years to packed houses in Moscow and Leningrad and was hailed as the first<br />

significant opera of the Soviet period.<br />

On January 26, 1936, Stalin went to see Lady Macbeth and two days later, the<br />

official government newspaper, Pravda, published an unsigned editorial called<br />

“Muddle instead of Music” that would change the course of Shostakovich’s life<br />

as well as that of Soviet music. More than a bad review, it amounted to a statement<br />

of official policy with respect to the arts, and the first practical application<br />

in music of the doctrine of Socialist Realism. The article also made an unmistakable<br />

threat:“This game may end badly....The peril of such distortions for Soviet<br />

music is clear. Leftist monstrosities in the opera are derived from the same<br />

sources as leftist monstrosities in art, in poetry, in pedagogy and in science.” A<br />

campaign of vilification followed.<br />

Although he followed the critical debate actively—carefully compiling a 90-page<br />

album of clippings—Shostakovich made no public answer to the charges, nor did<br />

he ever repudiate Lady Macbeth. Confused, hurt, and with a wife and his first child<br />

to support—his daughter Galina was born in May 1936—Shostakovich dropped<br />

out of the limelight for nearly two years. He continued composing, completing<br />

his Fourth Symphony (and withdrawing it before its premiere) and starting the<br />

Fifth, writing music for theater and film and romances on poems by Pushkin.<br />

In November 1937, Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony was given its successful premiere<br />

by Yevgeny Mravinsky in Leningrad, a milestone that marked the beginning<br />

of the composer’s return to official grace. The symphony was extensively discussed<br />

and praised in print, and Shostakovich published “My Creative Answer,” his<br />

first public response to the events of the preceding two years: “Among the<br />

reviews, which have frequently and very thoroughly analyzed this work, one gave<br />

me special pleasure, where it said that the Fifth Symphony is the practical creative<br />

answer of a Soviet artist to just criticism.” Shostakovich’s “answer” was very<br />

guarded and delayed until after the symphony had already been vetted by the<br />

Communist Party organization, music professionals, and the public. It is the<br />

source of one of the original myths about Shostakovich that he subtitled his Fifth<br />

Symphony “A Soviet Artist’s Reply to Just Criticism.” Shostakovich was not a fool;<br />

his professional and political standing was not so secure that he could risk second-guessing<br />

the reception and success of his new work. And this was not a patriotic<br />

cantata or oratorio; it was an abstract piece of music without text or program.<br />

Originated by an anonymous critic, the catchy phrase “A Soviet Artist’s Reply to<br />

Just Criticism” took on a life of its own.<br />

This was only the first occasion in Shostakovich’s life when self-defense would<br />

prove hopeless or suicidal. Many friends and colleagues fell victim to Stalin’s<br />

purges, others were victims of the siege of Leningrad and the war. The composer’s<br />

elder sister was exiled and his mother-in-law served time in the camps.<br />

Shostakovich learned from firsthand experience the need to keep his own counsel.<br />

He spoke of his music only with great reluctance, steering interlocutors to the<br />

music itself, leaving its interpretation and the extrapolation of any meanings,<br />

either obvious or “between the lines,” to critics, musicologists, and, ultimately, to<br />

his listeners. Knowing that music communicates on many different levels,<br />

Shostakovich refused to clarify or dictate the manner in which he wanted his<br />

music to be perceived.<br />

During World War II, the internal political strife of Soviet society, as deadly as it<br />

had become, paled before the patent threat to national survival. Prohibited from<br />

enlisting for active duty in his country’s defense and evacuated against his will<br />

from besieged Leningrad, Shostakovich served his country in the manner he<br />

knew best. The symbolic significance of his Seventh Symphony, the Leningrad<br />

Symphony—his spontaneous and highly charged response to Nazi invasion—is<br />

6<br />

7

hard to overestimate. As perhaps never before in history, a piece of music<br />

fulfilled the mission—both for his countrymen and for the Western Allies—<br />

as a galvanizing force, a source of heroic inspiration and resolve.<br />

Shostakovich’s very success in gauging and fulfilling the needs of his listeners<br />

was his personal downfall. The respect in which he was held by the international<br />

community and the influence that his music and stature exerted on<br />

other Soviet musicians made him, in 1948, the prime target of the renewed<br />

bout of cultural purges spearheaded by Stalin’s henchman, Andrey Zhdanov.<br />

Subjected to the most vicious, destructive, and irrational attacks of petty<br />

bureaucrats and opportunists—who had the full backing of the Party—<br />

Shostakovich could not hide. Never a status-seeking composer, never a social<br />

dissident, in order to survive he was obliged to swallow the last vestiges of<br />

pride and to embrace the criticism with gratitude.<br />

In the post-Stalin period, powerless to reject the role of public figure<br />

thrust upon him and visibly uncomfortable in the spotlight, Shostakovich<br />

nevertheless fulfilled his civic duties scrupulously. He served as an elected<br />

legislator, an official in the Union of Composers, a delegate to national and<br />

international congresses. He received untold honors and awards. In 1960,he<br />

became a member of the Communist Party. At the price of a personal sacrifice<br />

that is hard to calculate, he adopted a policy of nonresistance to his<br />

manipulation as a mouthpiece of the system. It is no secret that the platitudinous<br />

rhetoric he routinely delivered at official gatherings and the<br />

sometimes strident articles published over his signature were penned by<br />

others. Even so, to draw an absolute distinction between the pose he<br />

assumed and the truth of his inner convictions is extremely difficult. If he<br />

gave voice to the indignation and protest that so many wanted to hear<br />

him utter, it was through the language of music. Even here the signals<br />

could be mixed: while the philosophical reflections of his late symphonies,<br />

song cycles, and chamber works were haunting, he continued to compose<br />

music in a wide variety of genres, from a lighthearted musical comedy to<br />

settings of patriotic poetry and accessible film scores.<br />

Modest and unpretentious, Shostakovich was genuinely touched by the devotion<br />

to his music of some of the finest performers of his era, including Yevgeny<br />

Mravinsky, the Beethoven Quartet, David Oistrakh, Galina Vishnevskaya, and<br />

Mstislav Rostropovich. He viewed the performer with utmost respect as an<br />

essential collaborator in the creative process. Through direct involvement with<br />

the creation of his music, performers came as close to seeing the real<br />

Shostakovich as anyone could. Rostropovich has recalled that when he broke the<br />

news to the composer that he intended to leave the U.S.S.R. for good,<br />

Shostakovich “immediately started crying. He said, ‘In whose hands are you<br />

leaving me to die?’” Yet Shostakovich apparently never considered emigration a<br />

viable option.<br />

Not long before his death, Shostakovich agreed to an interview conducted by his<br />

son Maxim for a television documentary. Clearly uncomfortable before the camera<br />

even with his son, the elder Shostakovich’s reminiscences—elicited by showing<br />

him pictures of the past—were awkward and distanced, revealing little sense<br />

of emotional involvement. But the physical debilitation caused by years of illness<br />

and the unspoken torments of his inner world were vividly imparted: not through<br />

his words, but in the pathetically hunched shoulders, in the unrelenting nervous<br />

fidgeting, in the suffering etched on his face.<br />

—Laurel E. Fay, Scholar-in-Residence 2004<br />

If he never regained the self-assurance to challenge his own lot in life,<br />

Shostakovich did use his influence to help others in inconspicuous but significant<br />

ways. He campaigned for the rehabilitation of less fortunate victims<br />

of Stalin’s terror. He encouraged, directly and indirectly, young<br />

composers to pursue their individual paths. A non-Jew, he made impassioned<br />

musical protests against the anti-Semitism prevalent in his culture.<br />

The poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko has recalled the feeling of honor and vindication<br />

he felt in 1962 when, under fierce attack from the literary establishment<br />

for the publication of his “Babi Yar,” the great Shostakovich<br />

unexpectedly telephoned him to ask permission to set the poem to music.<br />

8<br />

9

1894<br />

Nicholas II ascends Russian<br />

throne<br />

1894–1903<br />

Minister of Finance Serge Witte<br />

leads major drive to develop<br />

industry and railroads<br />

1896<br />

Khodynka Fields catastrophe:<br />

more than 1,000 people crushed<br />

to death during coronation<br />

festivities<br />

1896–97<br />

St. Petersburg textile strikes<br />

1898<br />

Formation of Russian Social<br />

Democratic Workers’ Party<br />

(R.S.D.W.P.)<br />

1903<br />

Social Democrats split into<br />

Bolsheviks (under Lenin) and<br />

Mensheviks (under Martov);<br />

Kishinev anti-Semitic pogroms<br />

WEEKEND<br />

ONE<br />

FRIDAY<br />

AUGUST 13<br />

program one DMITRII <strong>SHOSTAKOVICH</strong>:<br />

THE MAN AND HIS WORK<br />

richard b. fisher center for the performing arts<br />

sosnoff theater<br />

8:00 p.m. Preconcert Talk Leon Botstein<br />

8:30 p.m. Performance<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

Three Fantastic Dances, Op. 5, for piano (1920–22)<br />

March in C Major<br />

Waltz in C Major<br />

Polka in C Major<br />

From Twenty-four Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87 (1950–51)<br />

No. 1 in C Major<br />

No. 3 in G Major<br />

Dénes Várjon, piano<br />

Piano Trio No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 67 (1944)<br />

Andante. Moderato<br />

Allegro con brio<br />

Largo attacca<br />

Allegretto<br />

Claremont Trio<br />

“Song of the Counterplan,” from Counterplan,Op.33 (1932)<br />

Andrey Antonov, bass<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

Four Songs on Texts of Dolmatovsky, Op. 86 (1950–51)<br />

The Motherland Hears<br />

Rescue Me<br />

He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not<br />

Sleep, My Darling Boy<br />

Lauren Skuce, soprano<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

Preface to the Complete Edition of My Works and a Brief Reflection<br />

Apropos of this Preface, for bass and piano, Op. 123 (1966)<br />

Andrey Antonov, bass<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

String Quartet No. 11 in F Minor, Op. 122 (1966)<br />

Introduction: Andantino<br />

Scherzo: Allegretto<br />

Recitative: Adagio<br />

Etude: Allegro<br />

Humoresque: Allegro<br />

Elegy: Adagio<br />

Finale: Moderato<br />

Bard Festival String Quartet<br />

intermission<br />

Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 1 (1934)<br />

Waltz<br />

Polka<br />

Foxtrot<br />

Bard Festival Chamber Players<br />

Gianmaria Griglio, conductor<br />

PROGRAM ONE NOTES<br />

This program brings together some of the most strikingly disparate items in Shostakovich’s oeuvre. We<br />

begin with the Three Fantastic Dances, Shostakovich’s first published work, which does not yet reveal the<br />

stature Shostakovich was soon to attain. The Twenty-four Preludes and Fugues present Shostakovich the<br />

classicist: the self-imposed task of engaging with forms and genres of the past not only gave the composer<br />

the satisfaction of competing with Bach on the technical level, but also enabled him to create new<br />

layers of meaning through his allusions to familiar idioms. The Jazz Suite demonstrates how well<br />

Shostakovich was able to assimilate the popular music of his day, but instead of producing a grotesque<br />

distortion for the higher purposes of art music, à la Mahler, he is able to enjoy the popular genres on<br />

their own level.“The Motherland Hears,” from the Dolmatovsky cycle, and the “Song of the Counterplan”<br />

10 11

1904<br />

Trans-Siberian Railway<br />

completed (begun 1891)<br />

1904–05<br />

Russo-Japanese War<br />

1905<br />

“Bloody Sunday” (January 9): beginning<br />

of the first Russian revolution; widespread<br />

disturbances throughout the<br />

country during the summer; Nicholas II<br />

issues the October Manifesto promising<br />

representative assembly and civil<br />

liberties (October 17)<br />

1906<br />

Convocation of the Duma, Russia’s<br />

first representative assembly<br />

(May 10); Pyotr Stolypin appointed<br />

Prime Minister<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich born in<br />

St. Petersburg on September 25<br />

Large street demonstration during<br />

the 1905 Revolution<br />

both offer an insight into Shostakovich as a successful official composer who could be heard every day<br />

on the radio in every Soviet workplace and household. And finally, we see Shostakovich as a great tragic<br />

artist in the two memorial pieces: the Second Piano Trio was composed in memory of Ivan Sollertinsky<br />

(1902–44), and the Eleventh Quartet in memory of Vassily Shirinsky (1901–65). Sollertinsky was one of<br />

Shostakovich’s closest friends during the 1930s; a brilliant historian and music critic, he was largely<br />

responsible for fostering Shostakovich’s fascination with Mahler and thus played an important role in<br />

shaping the composer’s mature style. As Stalin’s purges began, they were both interrogated as friends of<br />

the deposed Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky; the marshal was executed in 1937, but both musicians narrowly<br />

escaped arrest. Sollertinsky’s early death from heart failure was a great shock to the composer.<br />

Shirinsky was the first violinist of the Beethoven Quartet, which premiered most of Shostakovich’s quartets.<br />

Compared to the Trio, the Eleventh Quartet is more concise and restrained, the humor rather more<br />

chilling; its dense, elliptical manner is characteristic of Shostakovich’s late works.<br />

Three Fantastic Dances, Op. 5<br />

These relatively modest piano pieces show us a composer well grounded in compositional technique<br />

and clearly interested in new music—Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives were probably Shostakovich’s main<br />

model; there are also distinct references to popular genres. All three features characterize the more<br />

ambitious pieces of Shostakovich’s early career.<br />

From Twenty-four Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87<br />

Impressed by the performances of Bach’s entire “48” by the young Soviet pianist Tatyana Nikolayeva,<br />

Shostakovich decided to create his own cycle of preludes and fugues in every key. Most of the pieces are<br />

quite transparent in their texture and some even hint at Russian folk song idioms, which should have<br />

ensured their official approval; nevertheless, they were initially rejected by the Union of Composers on<br />

grounds of “formalism.”This decision was soon reversed, thanks to the cycle’s enthusiastic advocacy by<br />

leading Soviet pianists; since then, Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues have found a well-deserved<br />

place as core repertoire for pianists of all countries.<br />

Piano Trio No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 67<br />

This work, like the Piano Quintet and Cello Sonata, is an essay in neoclassicism, both in the transparency<br />

of the formal design and in the style of its thematic material. Shostakovich’s neoclassicism,<br />

however, inherited neither the frivolity of the French, nor the academic bent of the German variety, and<br />

the clear formal outlines only render the tragic force of the music more direct and powerful. The first<br />

movement begins with a slow introduction, the cello’s ethereal harmonics sounding higher than the<br />

violin’s response. This theme, initially reminiscent of Russian folk song, is developed contrapuntally and<br />

then, in a faster version, opens the main, allegro section of the movement. The dazzling Scherzo that<br />

follows vacillates between straightforward good humor and darker grotesqueries. The third movement<br />

is in stark contrast: a stern chord progression is announced in the piano, signaling the beginning of a<br />

baroque passacaglia form, one of Shostakovich’s favored vehicles for high tragedy. Six unchanging<br />

statements of the progression underpin the flowing, expressive funeral lament in the strings. The<br />

finale, based on a grotesque presentation of klezmer-style tunes, is a chilling danse macabre. Toward<br />

the end, however, this mood is twice dispelled by reminiscences: first, the slow theme of the introduction,<br />

which now soars over stormy piano writing, and then the final return of the passacaglia theme.<br />

Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 1<br />

In spite of its name, Shostakovich’s Jazz Suite No. 1 contains little that a modern listener would associate<br />

with jazz. This was not a personal eccentricity, since the Russian use of the word “jazz” in the 1920s<br />

and 1930s extended its scope to any popular genre emanating from the West. Shostakovich’s taste for<br />

such popular music made him vulnerable to attacks during the “fight against the foxtrot” instigated by<br />

the advocates of so-called proletarian art (“foxtrot” was a derogatory umbrella term). This gave rise to<br />

the first instance of Shostakovich making an official statement against his own inclinations for the<br />

sake of his career: he denounced the foxtrot trend in Soviet musical life and tried to dissociate himself<br />

from his celebrated Tahiti Trot (an arrangement of Vincent Youman’s “Tea for Two”). During the early<br />

1930s, the Stalinist state disbanded the “proletarianist” organizations responsible for such pressures,<br />

and a liking for Western-style popular music was no longer cause for shame. Stalin personally overruled<br />

the initial ban on the film Merry Fellows (1934), which featured the comic adventures of a jazz band as<br />

it worked its way up from obscurity to fame. Shostakovich’s suite of three jazz numbers was composed<br />

in this more relaxed atmosphere. The Waltz, with its wistful tune, follows the style of various popular<br />

hits played by bands in parks and gardens. The Polka is more agitated, and a little grotesque, owing to its<br />

roots in the circus-music tradition. The closing Foxtrot, with its dramatic changes and its oddly shifting<br />

harmonies, is the most artful of the three pieces, as if Shostakovich wanted to lavish special attention<br />

on this formerly despised dance.<br />

“Song of the Counterplan,” from the film Counterplan, Op. 33<br />

This song became Shostakovich’s first official hit. The film Counterplan, directed by Friedrich Ermler and<br />

Sergey Yutkevich, was much admired by Stalin himself. The rather bureaucratic title does nothing to<br />

suggest the uplifting and cheery character of the lyrics, which address a young woman as she wakes,<br />

telling her that in the day that awaits her she can rejoice in the joys of labor and love. The song was<br />

heard by generations of Soviet early risers on the radio each morning. It also became popular for a time<br />

in the United States owing to its use in the film Thousands Cheer (1943), where it appeared with new<br />

lyrics as “United Nations.”<br />

Four Songs on Texts of Dolmatovsky, Op. 86<br />

Although Yevgeny Dolmatovsky (1915–94) was by no means an artist of any profundity, he undoubtedly<br />

had a talent for clothing civic subjects in lyrical garb, thus providing welcome relief from the normal<br />

pomposity of Socialist Realist verse. The first song, “The Motherland Hears,” uses one of these quietly<br />

12 13

1907<br />

1907–09<br />

1911<br />

1912–17<br />

1913<br />

Childhood<br />

Convocation of the Second and Third<br />

Stolypin attempts agricultural<br />

Assassination of Stolypin<br />

Fourth Duma<br />

Tercentenary of the House<br />

Duma; Stolypin coup d’etat (June 3);<br />

reforms designed to promote<br />

(September)<br />

of Romanov<br />

change of electoral law and curtail-<br />

private ownership of land and<br />

ment of civil liberties<br />

modernize agriculture<br />

civic texts, somewhat unusual in its imaginative avoidance of the standard four-square rhyme scheme.<br />

Shostakovich provided the simplest of settings, and the remarkable success of his song was probably<br />

due more to luck than any intrinsic virtues of the setting: Dolmatovsky’s fanciful idea that the song could<br />

serve as a pilot’s “beacon” was transformed into exciting reality when Yuri Gagarin sang it upon his<br />

return from the first manned space flight—heard by millions of Soviet listeners. The first phrase of the<br />

song was soon adopted as the call sign of the principal Soviet radio station, imprinting the melody in the<br />

mind of almost every citizen of the Soviet Union. The other three songs of the cycle share the same lyric<br />

approach to civic subjects; however, they had no such lucky circumstances to lift them out of obscurity.<br />

Preface to the Complete Edition of My Works and a Brief Reflection Apropos of this Preface,Op.123<br />

Shostakovich, discomfited by the heavy solemnity of the official celebrations marking his 60th birthday,<br />

penned this strange satirical piece in response. Appropriating a well-known Pushkin epigram, he managed<br />

to satirize his own unstoppable productivity (at the time when the younger generation of composers<br />

saw this as a vice rather than a virtue). Then in the “brief reflection” that follows, he poked fun at his own<br />

musical signature DSCH (which had become ubiquitous in his recent works), and also at the string of official<br />

titles and honors he had been awarded as a leading Soviet artist.The piece was even performed in one<br />

of the anniversary concerts, as if the composer were raising his hands in gentle rebuff at excessive praise.<br />

String Quartet No. 11 in F Minor, Op. 122<br />

In this Quartet, Shostakovich abandons the form of a classical cycle, presenting instead a succession of<br />

short movements played without a break—a form that looks back to developments in the 1920s. These<br />

movements are ingeniously unified: the introduction features a theme with repeated notes and characteristic<br />

rhythm (short–short–long), which reappears in various guises in each of the following movements.<br />

The quartet is therefore akin to a set of variations, and Shostakovich evidently delighted in the<br />

unexpected transformations his theme undergoes: at one moment a solemn chorale, at another a raucous<br />

dance, and elsewhere a doleful funeral march. The “cuckoo” ostinato of the humoresque section is<br />

most likely a reference to an old Russian superstition: those who hear the cuckoo can discover how<br />

many years they still have to live by counting the number of calls.<br />

—Marina Frolova-Walker<br />

program two THE FORMATIVE YEARS<br />

olin hall<br />

1:00 p.m. Preconcert Talk Robert Martin<br />

1:30 p.m. Performance<br />

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)<br />

Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914)<br />

No. 1<br />

No. 2<br />

No. 3<br />

Colorado String Quartet<br />

Mikhail Gnesin (1883–1953)<br />

Song of a Knight Errant,Op.28 (1928)<br />

Andante<br />

Poco più mosso<br />

Colorado String Quartet<br />

Sara Cutler, harp<br />

Aleksandr Glazunov (1865–1936)<br />

From Four Preludes and Fugues, Op. 101 (1918–23)<br />

No. 2 in C-sharp Minor<br />

Dénes Várjon, piano<br />

Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953)<br />

Piano Sonata No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 28, “From Old Notebooks” (1917)<br />

Allegro tempestoso. Moderato. Allegro tempestoso<br />

Dénes Várjon, piano<br />

SATURDAY<br />

AUGUST 14<br />

panel one CONTESTED ACCOUNTS:<br />

THE COMPOSER’S LIFE AND CAREER<br />

Leon Botstein, moderator<br />

Malcolm Hamrick Brown; Laurel E. Fay; Elizabeth Wilson<br />

olin auditorium<br />

10:00 a.m. – noon<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

Piano Trio No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 8 (1923)<br />

Andante. Allegro. Moderato. Allegro<br />

Claremont Trio<br />

intermission<br />

14 15

1914–18<br />

First World War<br />

1915<br />

Starts piano lessons with his<br />

mother, first compositions<br />

1916<br />

Rasputin murdered<br />

(December 17)<br />

Rasputin<br />

1917<br />

February revolution (February–March); abdication of Nicholas II (March 2)<br />

and the fall of the Russian monarchy; creation of the Provisional Government;<br />

Enters Glyasser’s School of Music<br />

Lenin’s return to Russia (April 2); October–November: Bolsheviks overthrow<br />

the Provisional Government and establish communist dictatorship; abolition<br />

of civil liberties and freedom of the press; ban on opposition parties<br />

PROGRAM TWO NOTES<br />

Aleksandr Skriabin (1871–1915)<br />

Piano Sonata No. 9,Op.68, “Black Mass” (1912–13)<br />

Moderato quasi Andante. Molto meno vivo. Allegro.<br />

Più vivo. Allegro Molto. Alla Marcia. Più vivo. Allegro.<br />

Più vivo. Presto. Tempo I<br />

Dénes Várjon, piano<br />

Maximilian Shteynberg (1883–1946)<br />

Four Songs, Op. 14 (1924) (Tagore)<br />

I Will Care for the Grass<br />

No Quiet and No Peace<br />

When She Walked by<br />

Oh, Say Why<br />

William Ferguson, tenor<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Two Fables of Krylov, Op. 4 (1922)<br />

The Dragonfly and the Ant<br />

The Ass and the Nightingale<br />

Jessie Hinkle, mezzo-soprano<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Prelude and Scherzo, Op. 11, for string octet (1924)<br />

Colorado String Quartet<br />

Bard Festival String Quartet<br />

None of the three Shostakovich pieces in this program sounds like the composer in his maturity. The<br />

Krylov Fables are still well within the 19th-century Russian tradition of comic song, and the Trio is beautifully<br />

written in a late-Romantic style; the Octet is another matter, since it forges ahead in a fully modernist<br />

idiom that disappeared from Shostakovich’s work after the 1920s. The two more backward-looking<br />

pieces were a necessary part of Shostakovich’s assimilation of the past, while the Octet was one of a<br />

series of works that caused consternation for his teachers at the Petrograd Conservatory. To allow us to<br />

form an idea of these tensions, some songs by Shostakovich’s composition teacher, Maximilian<br />

Shteynberg, are included in the program (he was Rimsky-Korsakov’s pupil and son-in-law). The director<br />

of the Conservatory, Aleksandr Glazunov, is also represented in the program—he never advanced beyond<br />

the very polished style he had perfected more than two decades earlier. Shostakovich was clearly absorbing<br />

influences from outside the Conservatory, and the remainder of the program reflects this. The cult of<br />

Skriabin, still very strong in post-Revolutionary Russia, affected Shostakovich on a technical level (in his<br />

First Piano Sonata, for example), but he was temperamentally too remote from the mystical Skriabin to<br />

join this camp. Prokofiev’s modernism was a more congenial influence, both in its neoclassical and<br />

grotesque aspects, and it can be seen as one of the foundation stones in the creation of Shostakovich’s<br />

mature style. Stravinsky’s influence became noticeable only later, in the 1930s, when Shostakovich fell in<br />

love with the Symphony of Psalms. Finally, the “Jewish” strand, represented here by Gnesin’s piece, only<br />

emerged in Shostakovich’s works of the 1940s.<br />

Igor Stravinsky<br />

Three Pieces for String Quartet<br />

Stravinsky wrote this short cycle soon after his move to Switzerland, when his musical thinking still had<br />

pronounced Russian tendencies. The first piece is an imitation of an “endless” dance, whose brief<br />

melody is close to Russian folk types. The music of the Russian Orthodox liturgy, alternating between<br />

solo recitation and choral response, is reflected in the third piece. In both these pieces, very simple<br />

melodic material is given the dissonant modernist treatment characteristic of Stravinsky’s work at this<br />

time. The unpredictable twists and turns of the second piece look back to Petrushka, although<br />

Stravinsky cited the celebrated English clown “Little Titch” as his direct inspiration.<br />

Mikhail Gnesin<br />

Song of a Knight Errant,Op.28<br />

After visiting Palestine in the second decade of the 20th century, Mikhail Gnesin enthusiastically<br />

refashioned himself as a Jewish national composer. The Song of a Knight Errant, bearing the subtitle “In<br />

Memory of the Minnesinger Süsskind of Trimberg,” combines stereotypical “medieval” and “Jewish”<br />

musical elements. Its siciliano rhythm, light modal touches, and general melancholy are reminiscent of<br />

Musorgsky’s Il vecchio castello from the Pictures at an Exhibition. At the same time, the modal writing<br />

is elaborated with certain characteristic melodic touches and improvisatory figurations in the strings,<br />

providing the composer with the desired Jewish component.<br />

Aleksandr Glazunov<br />

From Four Preludes and Fugues, Op. 101<br />

After Glazunov became director of the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1905, he set about his new duties<br />

with enthusiasm, to the detriment of his compositional output. He steered the Conservatory ably<br />

through the Civil War period and remained in charge during the restructuring of the institution in the<br />

early 1920s—because the musicians around him complained that his music had fallen well behind the<br />

times, he perhaps felt that this work would be better appreciated. While many of the students who<br />

16 17

1918<br />

Lenin disbands the Constituent<br />

Assembly in January; separation of<br />

state and church; Trotsky announces the<br />

end of war with Germany (February 10);<br />

first Soviet constitution<br />

1918–21<br />

Civil War<br />

Street demonstration with<br />

“Communism” banner<br />

Trotsky addressing a crowd that<br />

included members of the middle and<br />

professional classes<br />

studied during his directorship complained about the burden of obligatory fugue writing (Shostakovich<br />

was no exception), Glazunov demonstrated in these pieces that excitement could still be injected into<br />

the old genre. The Four Preludes and Fugues are monumental pieces, where contrapuntal mastery is<br />

combined with Romantic gestures and textures. In the C-sharp minor pair, the whimsical prelude is contrasted<br />

with a weighty fugue, although both are based on the same material.<br />

Sergey Prokofiev<br />

Piano Sonata No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 28, “From Old Notebooks”<br />

Prokofiev completed this sonata as the October Revolution unfolded beneath his window. While it is<br />

tempting to see this as the inspiration for such a turbulent piece, the melodic material had been written<br />

years before, and the motoric style was already a Prokofiev trademark. The Sonata is in one movement,<br />

largely in a virtuosic and mercurial toccata manner, and with frequent harsh dissonances and<br />

grotesqueries. The only island of repose is the beautiful second theme, which is developed at length<br />

almost as if it were a separate slow movement; the main motif E–C–H(B)–E was derived from the name<br />

of a female admirer. This motif returns, transformed, in the violent development, and in the recapitulation<br />

it is almost unrecognizable—its original calm is banished as the Sonata hurtles to its close.<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Piano Trio No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 8<br />

This Trio belongs to Shostakovich’s Conservatory years and, although performed at the time in a student<br />

concert, it remained unpublished until after his death. There is only one movement, a self-sufficient<br />

sonata form with a substantial introduction and coda, following the Romantic tradition of Liszt<br />

and others. The introduction begins with a wistful motif, stated by each player in turn, surrounded by<br />

meandering harmonies; a livelier episode prepares the way for the Allegro. The Allegro’s opening theme<br />

owes much to Prokofiev, although it also foreshadows Shostakovich’s grotesque manner. The second<br />

theme is lushly Romantic, its broad melody and soft accompaniment in parallel triads pointing toward<br />

Rachmaninoff. It is this theme that eventually crowns the piece in a lyrical apotheosis, a fitting ending<br />

for a work that Shostakovich dedicated to his first love, Tatyana Glivenko.<br />

Aleksandr Skriabin<br />

Piano Sonata No. 9,Op.68, “Black Mass”<br />

The nickname “Black Mass” is not Skriabin’s own, but he was known to like it, and it prompted him to<br />

discuss what he saw as the “satanic” qualities of the piece. He said the opening was an induction into a<br />

world of darkness. A repeated-note motive then emerges, which he considered a satanic “incantation,”<br />

while the lyrical second subject exuded “evil charms.” The development and recapitulation surge forward<br />

in a single wave. Skriabin, in his own performances, rushed through the beginning of the recapitulation<br />

the sooner to reach his climactic point, where the second subject is transformed into a “march<br />

of evil forces.” Defying tonality but absolutely clear in its use of sonata form, this work is a tour de force.<br />

Maximilian Shteynberg<br />

Four Songs, Op. 14<br />

The Four Songs on verses by Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) present Shteynberg as an accomplished<br />

artist still clinging to certain late- and post-Romantic styles regarded as “decadent” by many of his contemporaries.<br />

The poems are opulent symbolist texts, rich in metaphor and erotically charged. The first is<br />

a celebration of love, the second longs for the unattainable and remote, the third portrays the first flutter<br />

of desire, while the final song warns mysteriously of a darker future. All of these themes are perfectly<br />

suited to Shteynberg’s rich Skriabinesque harmony, his echoes of sultry Russian and French Orientalism,<br />

and his subtle word-painting.<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Two Fables of Krylov, Op. 4<br />

The verse fables of Ivan Krylov (1769–1844), often based on Aesop, were usually the first moral lessons<br />

received by Russian children, and they had to be memorized at school both in Tsarist and Stalinist times.<br />

Shostakovich himself had acted out the fables at home in his youth. These two songs from his<br />

Conservatory days exhibit the kind of moment-by-moment characterization that had been established<br />

by Aleksandr Dargomïzhsky and Modest Musorgsky. The protagonists’ words, actions, and physical features<br />

are all minutely reflected in the music. The assurance with which Shostakovich tackles the genre<br />

of comic song is striking, and with hindsight, we can see here the birth of a great musical satirist.<br />

Prelude and Scherzo, Op. 11<br />

In these pieces for double string quartet, Shostakovich’s individual voice is already clearly discernible.<br />

The neoclassical Prelude begins with a Bachian recitative, whose pathos is shared by Shostakovich’s<br />

later Adagios. The linear polyphony of the piece, culminating in an eight-part canon, also became one<br />

of Shostakovich’s trademarks. While the Prelude is quite mellifluous, the Scherzo, by contrast, presents<br />

an aural assault characteristic of Soviet modernism in the 1920s. Although clearly beginning and ending<br />

in a G minor spiced with many “wrong” notes, it occasionally veers off into atonality and the fractured<br />

textures of Webern. The Scherzo strikes the listener as much by its indomitable vigor and capricious<br />

changes of direction as it does by its uniquely astringent sound. As Shostakovich expected (and<br />

hoped?), his Conservatory teacher Shteynberg was not amused. Bizarrely, someone trundled out this<br />

long-forgotten modernist onslaught in 1948, so that it could be added to the list of Shostakovich’s “formalist”<br />

misdemeanors; it then had the honor of being banned in the company of such grand works as<br />

the Eighth Symphony.<br />

—Marina Frolova-Walker<br />

18 19

1919<br />

1920<br />

1921<br />

1921–22<br />

1922<br />

Red Army victory in Crimea (May 17)<br />

Youth<br />

Communist victory<br />

Kronstadt revolt; Tenth Party<br />

Famine crisis<br />

Eleventh Party congress: Stalin is<br />

Passes entrance exam at Petrograd<br />

Studies composition with<br />

Congress: New Economic Policy<br />

elected General Secretary of the<br />

Conservatory in the fall<br />

Maximilian Shteynberg<br />

(NEP) and a resolution prohibiting<br />

Party; formation of the Union of<br />

Scherzo in F-sharp Minor, Op. 1<br />

factions in the Party passed<br />

Soviet Socialist Republics<br />

Art Life publishes first review<br />

Father dies (February 24)<br />

(September 27)<br />

Theme and Variations, Op. 3;<br />

Two Fables by Krylov, Op. 4;<br />

Three Fantastic Dances, Op. 5<br />

SATURDAY<br />

AUGUST 14<br />

program three FROM SUCCESS TO DISGRACE<br />

richard b. fisher center for the performing arts<br />

sosnoff theater<br />

7:00 p.m. Preconcert Talk Morten Solvik<br />

8:00 p.m. Performance American Symphony Orchestra,<br />

Leon Botstein, conductor<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

Theme and Variations in B-flat Major, Op. 3 (1921–22)<br />

Theme. Andantino<br />

1. Andantino<br />

2. Più mosso (Vivace)<br />

3. Andante<br />

4. Allegretto<br />

5. Andante<br />

6. Allegro<br />

7. Moderato. Allegro.<br />

8. Largo<br />

9. Allegro<br />

10. Allegro molto<br />

11. Appassionato<br />

Finale. Allegro. Maestoso. Coda. Presto<br />

Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 (1923–25)<br />

Allegretto. Allegro non troppo<br />

Allegro<br />

Lento<br />

Allegro molto<br />

intermission<br />

Symphony No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43 (1935–36)<br />

Allegretto poco moderato<br />

Moderato con moto<br />

Largo. Allegro<br />

PROGRAM THREE NOTES<br />

This evening’s program takes us from Shostakovich’s student days to his triumphant symphonic debut in<br />

1926, and then on to his dramatic fall from grace 10 years later. From the beginning of his conservatory<br />

studies, Shostakovich was widely recognized as an exceptional talent, and the fragile, bespectacled boy<br />

was protected from the worst hardships of the Civil War period. The First Symphony was the realization of<br />

the hopes placed in him, and it brought him immediate recognition in the Soviet Union (he celebrated the<br />

anniversary of the premiere for the rest of his life). Two years later, the symphony was even performed<br />

under the baton of Bruno Walter in Berlin. This success was followed by many others, and Shostakovich<br />

quickly gained celebrity status. But he had no intention of becoming a purveyor of instant classics, and<br />

instead he combined bold modernist experimentation with an appropriation of the music of the street and<br />

the circus. His newfound confidence, and the waywardness of his art, changed his public image, at times<br />

leading to accusations of arrogance and unpleasantness. He became an enthusiast for revolutionary and<br />

Soviet topics, approaching them with his customary flair, causing some jealousy among his less talented<br />

colleagues. Others felt he was wasting his talent on such topical works, which included ballets about a<br />

Soviet soccer team, industrial sabotage, and a collective farm. The same heads were shaken when he produced<br />

his first opera, The Nose, an absurdist farce with music as bizarre as Nikolai Gogol’s story.<br />

It was only with the appearance of his second opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, in 1934,<br />

that Shostakovich enjoyed near unanimous approval: the grotesque aspects of his art had certainly not<br />

disappeared, but they were now combined with powerful tragedy, signaling the passage from youth to<br />

maturity. Before long, Lady Macbeth had become the most celebrated and popular Soviet opera.<br />

Shostakovich was now clearly considered the foremost Soviet composer, bringing him a more comfortable<br />

life and financial security. He was married and this seemed a propitious moment to start a family. But this<br />

happy situation was not to last for long. In 1936, Lady Macbeth was suddenly attacked in the pages of<br />

Pravda as a decadent work that utterly failed to satisfy the demands of so-called Socialist Realism, as the<br />

new artistic policy was termed (its implications for music had not yet been spelled out). The criticisms<br />

clearly had authorization at the highest level, and so it was unsurprising, at a time when the great purges<br />

were beginning, that Shostakovich temporarily became a pariah among his colleagues and was reduced<br />

to poverty. He requested an audience with Stalin himself, but this was not granted. For the moment left<br />

without guidance, Shostakovich simply continued with his work in progress, the grandiose, Mahlerian<br />

Fourth Symphony. During rehearsals, Shostakovich became convinced that his only option was to withdraw<br />

the work from performance. Perhaps, at the last moment, he stifled a self-destructive urge to show<br />

his contempt for the authorities. Or perhaps he merely wanted to hear the symphony for himself, knowing<br />

that it ought not to be heard in public. In spite of his later return to official favor, he never sought to<br />

have the Fourth performed during Stalin’s lifetime. The premiere of this crucial work was astonishingly<br />

delayed until 1961, by which time younger Soviet composers were already becoming familiar with the<br />

music of the Western avant-gardists.<br />

20<br />

21

His father<br />

1923<br />

Constitution of U.S.S.R. adopted<br />

(July 6)<br />

Spends summer in a<br />

sanatorium in the Crimea<br />

Piano Trio No. 1,Op.8<br />

1924<br />

Death of Lenin (January 21)<br />

Begins to play in movie theaters<br />

1924<br />

Bust of Lenin in May Day parade in<br />

newly renamed Leningrad<br />

1926<br />

Premiere of Symphony No. 1,Op.10<br />

Theme and Variations in B-flat Major, Op. 3<br />

As this youthful work impressively demonstrates, Shostakovich had already mastered the style of Rimsky-<br />

Korsakov’s “St. Petersburg School” by the age of 16.The previous two generations of Russian composers had<br />

written many fresh and innovative works using the variation principle. Shostakovich follows in their footsteps<br />

by transforming his suitably plain and neutral theme into a mazurka, a scherzo, a “Turkish”march, and<br />

a Russian folk dance (among others). There are 11 variations in all, followed by a brilliant finale. (The first<br />

recording of the piece, with the London Symphony and Leon Botstein conducting, will be issued this fall.)<br />

Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10<br />

Like Prokofiev’s First Piano Concerto, Shostakovich’s First Symphony was an outstanding conservatory<br />

graduation piece that still has a place in the concert repertoire. It was also a worthy addition to the symphonic<br />

tradition of the St. Petersburg School: the themes are well-defined and memorable and their transformations<br />

and combinations carefully worked out; the harmony is adventurous without being<br />

outlandish; and the whole cycle is well balanced and classically transparent. Nevertheless, the symphony’s<br />

reception from the Conservatory professors, while positive, was not entirely smooth. The two most important<br />

symphonists among them qualified their admiration with certain reservations. Nikolay Myaskovsky<br />

was uncomfortable with the theatrical and bizarre aspects of the first movement—this deeply serious<br />

composer probably considered such qualities out of place at the beginning of a symphonic work (as<br />

opposed to the Scherzo, where such things were expected). Aleksandr Glazunov most probably disliked<br />

the overblown rhetoric of the last two movements, replete with dramatic silences and sententious instrumental<br />

soliloquies—such devices were quite contrary to his own predilections. With hindsight, we see<br />

that the First Symphony has more in common with the mature Shostakovich than the works that followed<br />

over the next few years, which were more pronouncedly modernist and experimental. Here, we can<br />

already see Shostakovich the master of the grotesque, the author of scherzos bristling with every shade<br />

of irony or sarcasm; we can already see his penchant for the relentless moto perpetuo, and we can foresee<br />

the blossoming of a dramatic symphonist who would eventually rival Tchaikovsky and Mahler.<br />

Symphony No. 4 in C Minor, Op. 43<br />

The criticisms in Pravda appeared after Shostakovich had already completed the first two of this symphony’s<br />

three movements, but he did nothing to conciliate the authorities when he wrote the Finale,<br />

which follows naturally from the first two movements as if nothing had happened. Either Shostakovich<br />

had not yet understood that he had to adjust his work to the demands of the state, or more likely he had<br />

no desire to destroy the integrity of his largest and most serious symphony to date. The Finale, of course,<br />

is tragic, but no more so than the first movement or Lady Macbeth—Shostakovich’s personal life had simply<br />

caught up with his artistic persona.<br />

The sprawling first movement thrusts us into a fractured world whose conflicts overshadow its<br />

unity. The opening theme unleashes the full force of the quadruple orchestra, the gravity of a Bach-like<br />

melody undermined by its wild scoring for shrill woodwind. The second main theme seems to come<br />

from a different world: a slow solo-bassoon monologue in a barren setting. The extreme contrast perhaps<br />

evokes the public and private duality found in Tchaikovsky’s symphonies. But these themes have<br />

no fixed character, for Shostakovich subsequently transforms them beyond anything we could have<br />

imagined: the undemonstrative second theme reappears harsh and strident in the brass, while the<br />

weighty opening theme is bizarrely recast as a mincing little polka. A frenzied fugato sweeps through<br />

the orchestra, and terrifying climaxes rip through the symphonic tissue six times. In this apparently<br />

anarchic world, the unexpected becomes normal, and the shocks seem to make no lasting difference.<br />

The movement is a study in deliberate incoherence that resists the embrace of any narrative.<br />

The second movement, a Mahlerian Ländler, is much shorter.The continuous tread of its triple meter<br />

guarantees a degree of unity, and beyond this, certain rhythms soon become almost mechanically persistent:<br />

there is the short–short–short–long heard from the opening, and also the short–short–long<br />

toward the end, a characteristic Shostakovich rhythm. These figures may lull the senses for a while, but<br />

their repetition eventually becomes unsettling. The detached and imperturbable character of the movement<br />

is eventually dispelled by a wild flurry of dissonance leading to an impetuous theme in the horns<br />

that would have sounded heroic but for the present context, which renders it more ominous.<br />

The Finale, once again, brings Mahler’s influence to the fore. A veritable cult of Mahler evolved<br />

in 1920s Leningrad, owing in part to the efforts of Shostakovich’s close friend and Mahler enthusiast,<br />

the musicologist Ivan Sollertinsky. By 1936, however, it was clear that the Mahler path was<br />

incompatible with Socialist Realism: a year earlier a symphony of Mahlerian scale and ambition by<br />

Gavriil Popov was banned from performance. Moreover, after the Lady Macbeth debacle,<br />

Shostakovich was explicitly advised by officials to free himself from the influence of Sollertinsky<br />

(and thus from the influence of Mahler). The Finale of the Fourth shows that Shostakovich did<br />

exactly the opposite: the beginning is a grotesque funeral march so close to Mahler that it could<br />

qualify as pastiche. The sequence of musical events here is even more baffling than in the first movement:<br />

the funeral march is followed by an Allegro that turns the orchestra into an enormous unstoppable<br />

machine. Suddenly everything is quiet, and a grotesque polka rings out, initiating a long suite<br />

of dances and marches that seem to unfold like a dream sequence. At the end of this aimless wandering,<br />

there is some sense of arrival: we reach a clear C-major triad. A gargantuan coda ensues, with the<br />

timpani insisting on the C in the bass, no matter what is happening in the rest of the orchestra. This<br />

is a moment of the highest emotional intensity: a Mahlerian chorale rings out, the triumph undercut<br />

by a cry of pain. Minor tonality replaces major with the return of the funeral march, and the symphony<br />

closes enigmatically with the sounds of the celeste.<br />

—Marina Frolova-Walker<br />

22 23

1927<br />

1928<br />

1929<br />

1929<br />

Trotsky expelled from the Communist<br />

First Five-Year Plan implemented (October 1); Soviet industrialization drive<br />

Liquidation of kulaks in Ukraine<br />

Vladimir Mayakovsky (standing, left),<br />

Party (exiled January 16, 1928)<br />

and forced collectivization of agriculture<br />

Composes first film score:<br />

Vsevolod Meyerhold (seated), and<br />

Finalist (honorable mention) at First<br />

Works temporarily in Meyerhold’s Moscow theater; Stokowski conducts<br />

New Babylon,Op.18<br />

the artist Alexander Rodchenko<br />

Chopin Competition in Warsaw<br />

Symphony No. 1 in Philadelphia<br />

Symphony No. 3, The First of May,<br />

discussing Shostakovich’s incidental<br />

Aphorisms,Op.13; Symphony No. 2,<br />

The Nose,Op.15<br />

Op. 20<br />

music to Mayakovsky’s Bedbug<br />

Dedication to October, Op.14<br />

SUNDAY<br />

AUGUST 15<br />

panel two MUSIC IN THE SOVIET UNION<br />

Christopher H. Gibbs, moderator<br />

Marina Frolova-Walker; David Nice; Maya Pritsker<br />

olin hall<br />

10:00 a.m. – noon<br />

program four THE PROGRESSIVE 1920s<br />

olin hall<br />

1:00 p.m. Preconcert Talk Simon Morrison<br />

1:30 p.m. Performance<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

Piano Sonata No. 1,Op.12 (1926)<br />

Allegro. Lento. Allegro<br />

Melvin Chen, piano<br />

Vladimir Sherbachov (1887–1952)<br />

From Songs, Op. 11, for voice and piano (1915–24) (Blok)<br />

That Life Has Passed<br />

Mary’s Hair Comes Unplaited<br />

I Will Forget Today<br />

Grey Smoke<br />

Courtenay Budd, soprano<br />

Anna Polonsky, piano<br />

Nikolay Myaskovsky (1881–1950)<br />

String Quartet No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 33,No.4 (1909–37)<br />

Andante. Allegro<br />

Allegretto risoluto<br />

Andante<br />

Allegro molto<br />

Colorado String Quartet<br />

intermission<br />

PROGRAM FOUR NOTES<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Aphorisms,Op.13 (1927)<br />

Recitative<br />

Serenade<br />

Nocturne<br />

Elegy<br />

March Funèbre<br />

Étude<br />

Dance of Death<br />

Canon<br />

Legend<br />

Lullaby<br />

Melvin Chen, piano<br />

Gavriil Popov (1904–72)<br />

Chamber Symphony, Op. 2, for seven instruments (1927)<br />

Moderato cantabile. Andante<br />

Scherzo: Allegro<br />

Largo<br />

Finale: Allegro energico. Fuoco<br />

Randolph Bowman, flute<br />

Laura Flax, clarinet<br />

Marc Goldberg, bassoon<br />

Carl Albach, trumpet<br />

Laura Hamilton, violin<br />

Jonathan Spitz, cello<br />

Jordan Frazier, double bass<br />

Fernando Raucci, conductor<br />

The Russian Civil War period saw a remarkable level of music making, with a continuation of operatic and<br />

concert life on the one hand, and ambitious new programs of mass music education on the other.With the<br />

end of the war and the introduction of the New Economic Policy, several factions of composers emerged<br />

from the resulting stability, most claiming some sort of inspiration from the Revolution, but with much disagreement<br />

over what post-Revolutionary music should be. Up to the end of the decade, the Soviet government<br />

refused, on principle, to give exclusive support to any particular artistic factions, and musicians were<br />

free both to compete for state grants and to seek remuneration privately, from box-office sales. The period<br />

24 25

1930<br />

Gulag system established<br />

Premiere of The Nose (January 18)<br />

1932<br />

Suicide of Nadezhda Allilueva, Stalin’s wife; proletarian arts organizations<br />

disbanded (April 23); Union of Soviet Composers formed<br />

Marries Nina Varzar (May 13)<br />

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District,Op.29<br />

1932–33<br />

Man-made famine in Ukraine<br />

1933<br />

Piano Concerto No. 1,Op.35<br />

1934<br />

Assassination of Sergey Kirov<br />

(December 1)<br />

Premiere of Lady Macbeth<br />

(January 22)<br />

Cello Sonata, Op. 40<br />

of the most extravagant musical experiments had in fact already passed with the fading of hopes for world<br />

revolution—there were no more symphonies requiring the factory whistles of an entire city, or the sound<br />

of fleets of planes and battleships. Now avant-gardists experimented more soberly in music laboratories<br />

with microtonal music and electric instruments, while the Skriabinists carried forward the banner of their<br />

late prophet, and the self-styled proletarian composers turned out rousing songs and marches.<br />

The Association for Contemporary Music brought together the bulk of composers whose work fits<br />

into concert programs today; there were several conservatives among the membership, and others who<br />

met modernism partway, but the most vocal members were generally the most committed to modernist<br />

trends. The Association promoted the music of “advanced” Western composers, such as Berg,<br />

Hindemith, Krenek, and Stravinsky. Soviet composers of many colors benefited from the Association’s<br />

concerts. In Moscow, Myaskovsky’s dark expressionist symphonies were performed alongside Aleksandr<br />

Mosolov’s Iron Foundry, which imitated the noises of the factory in a joyful cacophony.<br />

In Petrograd/Leningrad, there were three leading progressives, all with very different styles,<br />

namely Shcherbachov, Popov, and Shostakovich—contemporary critics often ranked them in this order.<br />

And it was in this order, too, that they were denounced in the harsher atmosphere of the early Stalin<br />

period. Shcherbachov lost his teaching position at the Leningrad Conservatory in 1931, as a result of sustained<br />

attacks by the “proletarian musicians” (who were temporarily being supported by the state, for<br />

as long as this suited Stalin’s purposes). Popov’s extremely ambitious First Symphony was, in 1935, the<br />

first major work to be banned under the new, centralized system of control over the arts. The following<br />

year, Shostakovich came under fire for his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, even though the<br />

opera had initially been received very well. Unlike Shostakovich, who bounced back relatively quickly,<br />

Shcherbachov and Popov both suffered protracted creative crises before they finally reconciled themselves<br />

to Socialist Realism, almost losing their individuality in the process. It is in comparison with such<br />

formerly successful modernists that we realize how strong and resilient Shostakovich proved to be,<br />

both as a man and as an artist.<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Piano Sonata No. 1,Op.12<br />

Although written shortly after the neoclassical First Symphony, this Sonata is uncompromisingly modernist<br />

throughout. Shostakovich seems to begin in the world of Prokofiev’s Third Sonata, with a toccata/tarantella<br />

theme, but before long he increases the level of dissonance and atonality to the level of<br />

Mosolov, the most rebarbatively modernist of all the early Soviet composers. While elements of sonata<br />

form are certainly present, the structuring role of tonality is gone. The stormy opening material eventually<br />

gives way to the descending scales that herald the second part of the exposition—a jarring<br />

march followed by a more lyrical passage. The development presents all the previous material in combination,<br />

with complex textures, leading to a shattering climax that draws from late Skriabin, marked<br />

by pounding clusters at the low end of the keyboard. The march theme finally emerges from the chaos,<br />

but now transformed in almost every aspect: tempo, meter, and texture are all changed, and the<br />

melodic contours are inverted. This rarefied, static passage is the final respite before the hair-raising<br />

coda, which Shostakovich brings to a halt with a desultory octave C.<br />

Vladimir Shcherbachov<br />

From Songs, Op. 11 *<br />

The Russian intelligentsia perceived the death, in 1921, of the great poet Aleksandr Blok (b. 1880) as the<br />

end of an era (the era we now refer to as the “Silver Age”). Blok was the most respected of the pre-<br />

Revolutionary poets who welcomed the Revolution as a realization of their dreams. By the early 1920s,<br />

the dashing of revolutionary hopes, and the reality of the impoverished and deindustrialized country left<br />

by the Civil War, made their millennial rhetoric and mystical prognostications seem hopelessly out of<br />

touch. But for a time, the spirit of Blok—and of Skriabin—lingered on for certain artists during the 1920s.<br />

For Shcherbachov, Blok was simply “the greatest of poets,” and he planned to celebrate the late poet’s<br />

work in a two-evening program, one of chamber music (to include the songs of Op. 11), and the other<br />

symphonic (his Second Symphony included settings of Blok poems). While the chamber evening was to<br />

focus on the tragic individual, the symphonic evening would focus instead on a “cosmic indifference” to<br />

these earthly sorrows; these reflected two facets of the poet’s work.This contrast is present even in some<br />

of the individual texts chosen by Shcherbachov. Blok was revered not only for the character of his<br />

poetry. The sound of Blok’s language, its economy and subtle rhythmic ingenuity, made form and content<br />

inseparable. The music in the song “I Will Forget Today” opens with a nearly minimalist clarity that<br />

is followed by a more active and agitated section, properly reflecting Blok’s evocation of death. The<br />

third section is a harmonically imaginative synthesis that highlights through subtle variation the brilliance<br />

of the composer’s favorite poet.<br />

Nikolay Myaskovsky<br />

String Quartet No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 33,No.4<br />

This Quartet was originally written as a graduation piece in 1909–10, but Myaskovsky revised it for publication<br />

in 1937. In fact, this was only one of several unpublished early works that he returned to in the<br />

1930s and 1940s—evidently he felt that they would flourish better in the era of Socialist Realism than<br />

any of his dark and troubled works of the 1910s and 1920s. But this does not mean that the Quartet is<br />

a mere historic curiosity; like almost everything from this composer’s pen, it displays the thoroughness<br />

of thematic development and elegance of form that Myaskovsky inherited from the St. Petersburg<br />

tradition, while the constant lyrical-dramatic current that propels the music forward betrays the<br />

composer’s admiration for Tchaikovsky. But the nervous anxiety of the outer movements, the angularity<br />

of the themes, and the avoidance of a major-key “happy ending” are all highly characteristic of<br />

Myaskovsky’s maturity.<br />

* We thank Elena Khodorkovskaya, Smolny College, and the staff of the Russian Institute of the History of Arts, St.<br />

Petersburg, for providing the music.<br />

26 27

1935–38<br />

1936<br />

1937<br />

Great Purges; show trials; mass<br />

terror<br />

Pravda publishes attacks on Lady<br />

Macbeth (“Muddle instead of Music,”<br />

Daughter Galina practices her “own”<br />

cycle<br />

Red Army Marshal Tukhachevsky and seven generals shot (June);<br />

height of Great Terror<br />

January 28) and The Limpid Stream<br />

Teacher of composition and instrumentation at Leningrad Conservatory<br />

(“Balletic Falsehood,” February 6);<br />

(1937–41)<br />

daughter Galina born (May 30)<br />

Symphony No. 5,Op.47<br />

Symphony No. 4,Op.43<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich<br />

Aphorisms,Op.13<br />

The Aphorisms were Shostakovich’s response a decade later to Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives. Both works<br />

are collections of brief and varied pieces, each based on a single distinctive compositional task,<br />

although Shostakovich’s pieces were additionally filtered through the eclectic and sometimes absurdist<br />

modernism of the Soviet 1920s. Unlike Prokofiev, Shostakovich also chose to specify genres for his<br />

pieces, thereby creating a further opportunity for irony: the Nocturne is hopelessly disjointed, as if a<br />

negation of its supposed genre, and the final piece, Lullaby, is a white-notes baroque Adagio, sleepinducing<br />

because of its deliberate lack of interest. From the extreme of the Lullaby, there are various<br />

approaches to tonality: the Étude is in a clear C major until its “wrong” final chord, the Dance of Death<br />

uses the Dies Irae motive in a bitonal context, and the pointillist Canon is rigorously atonal. Anything is<br />

possible, and everything is permissible—a faithful reflection of the Soviet musical world of that moment.<br />

Gavriil Popov<br />

Chamber Symphony, Op. 2<br />

Popov’s Chamber Symphony was one of the most celebrated works to emerge from the Soviet 1920s.<br />

While various neoclassical influences are easily discernible (Prokofiev, Stravinsky, and Hindemith), the<br />

result is surprisingly individual thanks to the poetry of Popov’s broad themes, his unusual polyphonic<br />

textures, and his unpredictability. The ensemble of violin, cello, double bass, flute, clarinet, bassoon, and<br />

trumpet is employed with great variety, drawing upon associations both classical and romantic, serious<br />

and popular, heroic and comic. The first movement opens with a lyrical flute theme, its initial pastoral<br />

calm giving way to a more improvisatory mode of expression. A trumpet call signals the entry of harsher<br />

sounds, but even then the first theme, ever changing, continues to dominate the movement. The second<br />

movement is a Scherzo with kaleidoscopic changes of rhythms and complex polyphonic textures. A contrasting<br />

Trio looks toward Prokofiev, while the coda is a somewhat grotesque moto perpetuo. The Largo<br />

begins with a noble contemplative theme, but the sounds of popular dance music arrive with the second<br />

theme, a sensuous melody over a static bass that is quite spellbinding. The Finale reintroduces the<br />

grotesque element with an angular chromatic theme that seems to have fallen out of a fugue. After a<br />

brief reappearance of the Trio theme from the second movement, the Finale’s theme does indeed prove<br />

to be a fugue subject, which turns ugly in its inversion. More themes from the earlier movements make<br />

their return, as if to round off the work with a grand romantic gesture. But Popov deliberately undermines<br />

the effect, and in the end the apotheosis is eaten away by the grotesque.<br />

SUNDAY<br />

AUGUST 15<br />

program five THE ONSET OF POLITICAL REACTION<br />

richard b. fisher center for the performing arts<br />

sosnoff theater<br />

4:30 p.m. Preconcert Talk Marina Frolova-Walker<br />

5:00 p.m. Performance<br />

Dmitrii Shostakovich (1906–75)<br />

Oath to the People’s Commissar, for bass, chorus, and piano (1941)<br />

From Ten Russian Folk Songs (1951)<br />

A Clap of Thunder over Moscow<br />

What Are These Songs<br />

Daniel Gross, bass-baritone<br />

Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director<br />

Mihae Lee, piano<br />

Ivan Dzerzhinsky (1909–78)<br />

From The Quiet Don (1934)<br />

Oh, How Proud Our Quiet Don<br />

From Border to Border<br />

John Hancock, baritone<br />

Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director<br />

Mihae Lee, piano<br />

Tikhon Khrennikov (b. 1913)<br />

From Into the Storm, Op. 8 (1936–39)<br />

Frol’s Tale of Lenin<br />

Chorus of Peasants<br />

Daniel Gross, bass-baritone<br />

Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director<br />

Mihae Lee, piano<br />

—Marina Frolova-Walker<br />

28 29

1938<br />

1939<br />

Shostakovich with his pupils at the<br />

Leningrad Conservatory<br />

Son Maxim born (May 10)<br />

Quartet No. 1,Op.49<br />

Maxim<br />

Non-Aggression Pact signed by Hitler and Stalin (August 23); outbreak of<br />

World War II (September 3); Soviet troops cross Polish frontier (September 17);<br />

U.S.S.R. attacks Finland (November 30)<br />

Symphony No. 6,Op.54<br />