Spaces Vol 1 Is 6

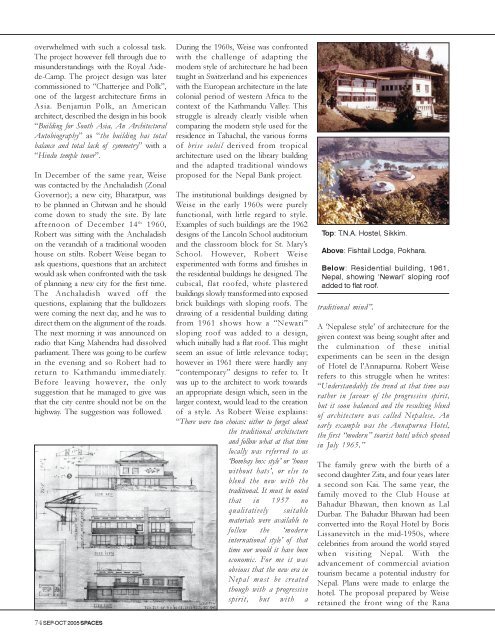

overwhelmed with such a colossal task. The project however fell through due to misunderstandings with the Royal Aidede-Camp. The project design was later commissioned to “Chatterjee and Polk”, one of the largest architecture firms in Asia. Benjamin Polk, an American architect, described the design in his book “Building for South Asia, An Architectural Autobiography” as “the building has total balance and total lack of symmetry” with a “Hindu temple tower”. In December of the same year, Weise was contacted by the Anchaladish (Zonal Governor); a new city, Bharatpur, was to be planned in Chitwan and he should come down to study the site. By late afternoon of December 14 th 1960, Robert was sitting with the Anchaladish on the verandah of a traditional wooden house on stilts. Robert Weise began to ask questions, questions that an architect would ask when confronted with the task of planning a new city for the first time. The Anchaladish waved off the questions, explaining that the bulldozers were coming the next day, and he was to direct them on the alignment of the roads. The next morning it was announced on radio that King Mahendra had dissolved parliament. There was going to be curfew in the evening and so Robert had to return to Kathmandu immediately. Before leaving however, the only suggestion that he managed to give was that the city centre should not be on the highway. The suggestion was followed. During the 1960s, Weise was confronted with the challenge of adapting the modern style of architecture he had been taught in Switzerland and his experiences with the European architecture in the late colonial period of western Africa to the context of the Kathmandu Valley. This struggle is already clearly visible when comparing the modern style used for the residence in Tahachal, the various forms of brise soleil derived from tropical architecture used on the library building and the adapted traditional windows proposed for the Nepal Bank project. The institutional buildings designed by Weise in the early 1960s were purely functional, with little regard to style. Examples of such buildings are the 1962 designs of the Lincoln School auditorium and the classroom block for St. Mary’s School. However, Robert Weise experimented with forms and finishes in the residential buildings he designed. The cubical, flat roofed, white plastered buildings slowly transformed into exposed brick buildings with sloping roofs. The drawing of a residential building dating from 1961 shows how a “Newari” sloping roof was added to a design, which initially had a flat roof. This might seem an issue of little relevance today; however in 1961 there were hardly any “contemporary” designs to refer to. It was up to the architect to work towards an appropriate design which, seen in the larger context, would lead to the creation of a style. As Robert Weise explains: “There were two choices: either to forget about the traditional architecture and follow what at that time locally was referred to as ‘Bombay box style’ or ‘house without hats’, or else to blend the new with the traditional. It must be noted that in 1957 no qualitatively suitable materials were available to follow the ‘modern international style’ of that time nor would it have been economic. For me it was obvious that the new era in Nepal must be created though with a progressive spirit, but with a Top: T.N.A. Hostel, Sikkim. Above: Fishtail Lodge, Pokhara. Below: Residential building, 1961, Nepal, showing ‘Newari’ sloping roof added to flat roof. traditional mind”. A ‘Nepalese style’ of architecture for the given context was being sought after and the culmination of these initial experiments can be seen in the design of Hotel de l’Annapurna. Robert Weise refers to this struggle when he writes: “Understandably the trend at that time was rather in favour of the progressive spirit, but it soon balanced and the resulting blend of architecture was called Nepalese. An early example was the Annapurna Hotel, the first “modern” tourist hotel which opened in July 1965.” The family grew with the birth of a second daughter Zita, and four years later a second son Kai. The same year, the family moved to the Club House at Bahadur Bhawan, then known as Lal Durbar. The Bahadur Bhawan had been converted into the Royal Hotel by Boris Lissanevitch in the mid-1950s, where celebrities from around the world stayed when visiting Nepal. With the advancement of commercial aviation tourism became a potential industry for Nepal. Plans were made to enlarge the hotel. The proposal prepared by Weise retained the front wing of the Rana 74 SEP-OCT 2005 SPACES

palace and framed it with a ‘Nepalese’ style building in the back. It is of course interesting to compare this design to what has subsequently been done to give the palace a special ‘Nepalese’ identity; by adding ‘pagoda style’ roofs to the Ranastyle building. PROFILE§ In 1967, the Chhogyal of Sikkim called Weise to Delhi in connection with the foreseen Sikkim House project. The audience was given at the Rastapati Bhawan, and the Chhogyal came straight to the point; “How would you perceive the Sikkim House to look?” So Robert Weise had to sketch out a design there and then, which the Chhogyal accepted. The Sikkim House was to be constructed exactly as shown in the sketches. This meeting was followed by a close relationship with the Chhogyal who asked Robert Weise to develop a ‘Sikkim Style’ of architecture. By the end of the 1960s, several projects had commenced in Gangtok, which reflected this newly conceived ‘Sikkim Style’; T. N. A. Hostel, T. N. Higher Secondary School and the Palace Secretariat. The 1960s was a decade of experimentation for Weise, which brought out some of the most interesting designs. In addition to the projects already referred to above, there were numerous residential buildings, schools and projects related to tourism. One project must be mentioned here in particular, the Fishtail Lodge in Pokhara. A simple design and the use of local materials created an environment that reflected the essence of Pokhara and captured its identity. WCAE In 1969 the firm ‘Weise Consulting Architects & Engineers’ was registered. The office grew quickly to comprise of at times up to 25 staff with a branch office in Sikkim. The next five years was the most productive period of Robert Weise’s career, during which over 100 projects were designed. In Kathmandu the most prominent of these projects were Hotel Malla, the Army Headquarters and the SOS Children’s Village in Sano-Thimi. The Hotel Yellow Pagoda on Kantipath was constructed. Several hotel projects were designed but never constructed, such as the impressive design for the extension of Hotel Annapurna for Hilton. Army complexes were carried out in Chhauni, Baneshwor, Bhaktapur, Karipati, Pokhara and Nepalganj. Parallel to the projects in Nepal, there were some projects in Sikkim, many of which however ended up not being built, for history struck again. On May 16th 1975, Sikkim became the 22nd State of the Indian Union. With the transition of power, many of the projects conceptualized by the Chogyal were scrapped and for those that were later implemented, Weise’s services were no longer sought. In 1976, the office and residence was moved to Keshar Mahal, a building designed by Robert Weise. After Sikkim, a slight hint of fatigue shimmers through in Robert Weise’s work. The second half of the 1970’s led to a double heart attack in 1979. During this period there were however several major projects such as Top: SOS Children’s Village, Kathmandu. Above left: Hotel Yellow Pagoda, Kathmandu. Above right: Japanese Embassy staff quarters, Kathmandu. the west-wing extension of the Hotel de l’Annapurna, the Geodatical Observatory in Nagarkot, the Japanese Embassy Staff Quarters in Jawalakhel, and work on the Soviet Embassy had already begun. In his book “Wege und Irrwege der Entwicklungshilfe” (Paths and Erring-Paths of Development Aid), Dr. Toni Hagen presented Robert Weise’s work as a highly successful example of development aid through private initiative. During the period 1959 to 1979, a Swiss architect, without any foreign financing, provided practical training to 22 architects and 80 SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 75

- Page 23 and 24: “When I was a kid, elders would a

- Page 25 and 26: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 25

- Page 27 and 28: Emerald Pools SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 2

- Page 29 and 30: figurines in a spiral arrangement (

- Page 31 and 32: Text: Kathmandu Valley Preservation

- Page 33 and 34: The restoration of Kal Bhairav was

- Page 35 and 36: mortar. On removal of this cladding

- Page 37 and 38: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 37

- Page 39 and 40: This view is in fact one of the key

- Page 41 and 42: Traditionally, hotels and resorts h

- Page 43 and 44: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 43

- Page 45 and 46: axis’s - rather, structures occur

- Page 47 and 48: unavoidable in most Pokhara images.

- Page 49 and 50: Resort has 61 standard rooms, all o

- Page 51 and 52: CRAFTS DRIFTING T O W A R D S FAME

- Page 53 and 54: is?” No need to guess, it clearly

- Page 55 and 56: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 55

- Page 57 and 58: HOTEL WITH A HISTORY Nov/Dec 2004 T

- Page 59 and 60: JOURNEY THROUGH S P A C E S FLAUNTI

- Page 61 and 62: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 61

- Page 63 and 64: INTERIOR Text: Sonia Gupta The wall

- Page 65 and 66: colour all around. These lights are

- Page 67 and 68: Sonia Text: A.B. Shrestha Sonia’s

- Page 69 and 70: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 69

- Page 71 and 72: ARCHITECT ROBERT WEISE: Text: Kai W

- Page 73: PROFILE§ Above: Royal Palace propo

- Page 77 and 78: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 77

- Page 79 and 80: About one and a half kilometres fro

- Page 81 and 82: Above: One is treated to such a sig

- Page 83 and 84: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 83

- Page 85 and 86: - all with attached bathrooms - con

- Page 87 and 88: a bypass road for Greater Kathmandu

- Page 89 and 90: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 89

- Page 91 and 92: Kathmandu Patan Bhaktapur ZONE A: S

- Page 93 and 94: Quality output calls for quality in

- Page 95 and 96: ACCESS BOON FOR HOUSING COLONIES Ma

- Page 97 and 98: SPACES SEP-OCT 2005 97

- Page 99 and 100: Picture framing is an art by itself

- Page 101 and 102: SURFACE PREPARATION 7. Newly plaste

- Page 103 and 104: complementary of the background col

- Page 105 and 106: TRANSITIONAL HICCUPS Courtesy: Dr.

- Page 107 and 108: Oak Tree Celebrating The Grand open

overwhelmed with such a colossal task.<br />

The project however fell through due to<br />

misunderstandings with the Royal Aidede-Camp.<br />

The project design was later<br />

commissioned to “Chatterjee and Polk”,<br />

one of the largest architecture firms in<br />

Asia. Benjamin Polk, an American<br />

architect, described the design in his book<br />

“Building for South Asia, An Architectural<br />

Autobiography” as “the building has total<br />

balance and total lack of symmetry” with a<br />

“Hindu temple tower”.<br />

In December of the same year, Weise<br />

was contacted by the Anchaladish (Zonal<br />

Governor); a new city, Bharatpur, was<br />

to be planned in Chitwan and he should<br />

come down to study the site. By late<br />

afternoon of December 14 th 1960,<br />

Robert was sitting with the Anchaladish<br />

on the verandah of a traditional wooden<br />

house on stilts. Robert Weise began to<br />

ask questions, questions that an architect<br />

would ask when confronted with the task<br />

of planning a new city for the first time.<br />

The Anchaladish waved off the<br />

questions, explaining that the bulldozers<br />

were coming the next day, and he was to<br />

direct them on the alignment of the roads.<br />

The next morning it was announced on<br />

radio that King Mahendra had dissolved<br />

parliament. There was going to be curfew<br />

in the evening and so Robert had to<br />

return to Kathmandu immediately.<br />

Before leaving however, the only<br />

suggestion that he managed to give was<br />

that the city centre should not be on the<br />

highway. The suggestion was followed.<br />

During the 1960s, Weise was confronted<br />

with the challenge of adapting the<br />

modern style of architecture he had been<br />

taught in Switzerland and his experiences<br />

with the European architecture in the late<br />

colonial period of western Africa to the<br />

context of the Kathmandu Valley. This<br />

struggle is already clearly visible when<br />

comparing the modern style used for the<br />

residence in Tahachal, the various forms<br />

of brise soleil derived from tropical<br />

architecture used on the library building<br />

and the adapted traditional windows<br />

proposed for the Nepal Bank project.<br />

The institutional buildings designed by<br />

Weise in the early 1960s were purely<br />

functional, with little regard to style.<br />

Examples of such buildings are the 1962<br />

designs of the Lincoln School auditorium<br />

and the classroom block for St. Mary’s<br />

School. However, Robert Weise<br />

experimented with forms and finishes in<br />

the residential buildings he designed. The<br />

cubical, flat roofed, white plastered<br />

buildings slowly transformed into exposed<br />

brick buildings with sloping roofs. The<br />

drawing of a residential building dating<br />

from 1961 shows how a “Newari”<br />

sloping roof was added to a design,<br />

which initially had a flat roof. This might<br />

seem an issue of little relevance today;<br />

however in 1961 there were hardly any<br />

“contemporary” designs to refer to. It<br />

was up to the architect to work towards<br />

an appropriate design which, seen in the<br />

larger context, would lead to the creation<br />

of a style. As Robert Weise explains:<br />

“There were two choices: either to forget about<br />

the traditional architecture<br />

and follow what at that time<br />

locally was referred to as<br />

‘Bombay box style’ or ‘house<br />

without hats’, or else to<br />

blend the new with the<br />

traditional. It must be noted<br />

that in 1957 no<br />

qualitatively suitable<br />

materials were available to<br />

follow the ‘modern<br />

international style’ of that<br />

time nor would it have been<br />

economic. For me it was<br />

obvious that the new era in<br />

Nepal must be created<br />

though with a progressive<br />

spirit, but with a<br />

Top: T.N.A. Hostel, Sikkim.<br />

Above: Fishtail Lodge, Pokhara.<br />

Below: Residential building, 1961,<br />

Nepal, showing ‘Newari’ sloping roof<br />

added to flat roof.<br />

traditional mind”.<br />

A ‘Nepalese style’ of architecture for the<br />

given context was being sought after and<br />

the culmination of these initial<br />

experiments can be seen in the design<br />

of Hotel de l’Annapurna. Robert Weise<br />

refers to this struggle when he writes:<br />

“Understandably the trend at that time was<br />

rather in favour of the progressive spirit,<br />

but it soon balanced and the resulting blend<br />

of architecture was called Nepalese. An<br />

early example was the Annapurna Hotel,<br />

the first “modern” tourist hotel which opened<br />

in July 1965.”<br />

The family grew with the birth of a<br />

second daughter Zita, and four years later<br />

a second son Kai. The same year, the<br />

family moved to the Club House at<br />

Bahadur Bhawan, then known as Lal<br />

Durbar. The Bahadur Bhawan had been<br />

converted into the Royal Hotel by Boris<br />

Lissanevitch in the mid-1950s, where<br />

celebrities from around the world stayed<br />

when visiting Nepal. With the<br />

advancement of commercial aviation<br />

tourism became a potential industry for<br />

Nepal. Plans were made to enlarge the<br />

hotel. The proposal prepared by Weise<br />

retained the front wing of the Rana<br />

74 SEP-OCT 2005 SPACES