You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

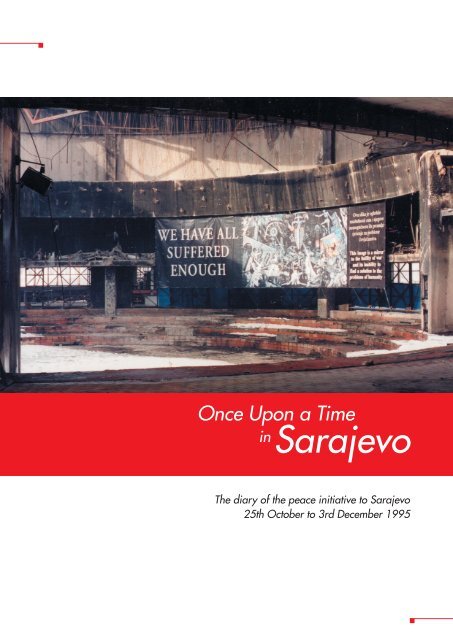

Once Upon a Time<br />

in Sarajevo<br />

The diary of the peace initiative to Sarajevo<br />

25th October to 3rd December <strong>1995</strong>

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Contents<br />

Introduction to Sarajevo<br />

Historical Background to the Seige<br />

of Sarajevo 1992-1996<br />

Synopsis of the Journey of the<br />

<strong>Peace</strong> <strong>Project</strong> to Sarajevo in <strong>1995</strong><br />

Cast of Characters of Once Upon<br />

a Time In Sarajevo<br />

The Diary of Dominic Ryan: The<br />

Journal of Sarajevo 26th October<br />

to 3rd December <strong>1995</strong>

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Introduction to Sarajevo<br />

Ideas are like children that take time and<br />

patience to be born, grow and develop. So with<br />

the idea of bringing a humanitarian painting and<br />

its message to Russia, it took a long time before<br />

that idea bore fruit. I had to be patient to see<br />

a whole series of stages complete themselves.<br />

Sometimes destiny is kind in its cruelty. Without<br />

these postponements in Moscow I would never<br />

have met Darja and I definitely would never have<br />

been inspired to step into the chaos, brutality and<br />

numbing suffering of a war zone. The very act of<br />

such events conspiring against me in Moscow had<br />

propelled me into a new and unknown career.<br />

Had everything gone to plan, if the exhibition had<br />

gone ahead as planned, I would have immediately<br />

returned to Australia and continued my life as an<br />

artist. But experiencing these postponements in<br />

Moscow helped me to understand that what I should<br />

do next was to bring with Darja a symbol into a war<br />

zone—an area that was similar to the landscape<br />

of the painting. Out of the Moscow exhibition,<br />

I understood clearly that what I was doing was<br />

smuggling an artwork and a message into a war<br />

zone.<br />

After Michelle and I were rendered homeless<br />

in Moscow, after I had met Darja, the next step<br />

was a natural one. I had a strong desire to attempt<br />

this time to bring the message of the mural into<br />

a new but hostile environment and let it speak to<br />

people. The direction that I had taken began to<br />

alter. Sometimes when we set out on a path and<br />

the direction of this path veers a couple of degrees;<br />

the more we walk upon this path, the greater that<br />

angle becomes. So what begins as a mere couple of<br />

degrees over time veers far away from our original<br />

point of departure.<br />

When I returned to Australia, life continued on<br />

in a muted fashion. I had rented a small pink wooden<br />

double-fronted house in Collingwood, an industrial<br />

suburb in the centre of Melbourne. Michelle, my<br />

Australian girlfriend from Moscow, was again<br />

living with me, having returned from Queensland.<br />

During this time over eight months I continued to<br />

correspond with Darja. The plan that we would go to<br />

Sarajevo was slowly mulled over in our minds. I went<br />

to see Tahir Gambis, an Australian-Bosnian actor,<br />

who was contemplating travelling to Bosnia before<br />

me, and who was hoping to make a film about the<br />

siege in Sarajevo.<br />

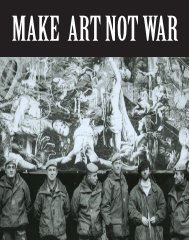

The mission for Darja as my guide and assistant<br />

and I, was to smuggle a humanitarian billboard,<br />

the image of the Millennium into Sarajevo, The<br />

message I wanted to incorporate with the billboard<br />

image was ‘We Have All Suffered Enough’. I went<br />

to a company called Colour Graphics in Australia<br />

and we created this forty-eight foot by fifteen-foot<br />

image which was printed on a plasticised tarpaulin.<br />

I rented a Hi-8 camera, and a couple of bolts and<br />

screw drivers. I contacted various embassies<br />

and after research and financial support I flew<br />

to Slovenia where I rendez-voused with Darja in<br />

Ljubljana. From there we travelled to her family’s<br />

house in Maribor before deciding to enter Sarajevo.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Historical Background To The Seige Of Sarajevo 1992-1996<br />

Yugoslavia began to disintegrate following the<br />

collapse of Communist regimes in other parts of<br />

Eastern Europe in 1989. In June 1991, the state of<br />

Slovenia declared its independence, closely followed<br />

by Croatia.<br />

Despite opposition from other member states in<br />

the European Union, Germany recognised Slovenia<br />

and Croatia in December 1991. Other EU countries<br />

followed. This had immense consequences: it left<br />

Yugoslavia as a Serbian-dominated rump state.<br />

This was intolerable for Muslims in Bosnia, who<br />

had lived amicably with Serbs and Croats in Bosnia<br />

for 40 years, and whose ideal was a multinational<br />

Yugoslavia, but who now faced being a vulnerable<br />

minority in a state ruled by Serb nationalists.<br />

A referendum on Bosnian independence was<br />

held in February 1992. The Bosnian Serbs boycotted<br />

it, because they did not want to be separated<br />

from their brethren in Serbia. Since the Muslims<br />

(44%) and Croats (17%) made up a majority of<br />

Bosnia’s population, the referendum produced an<br />

overwhelming vote for independence.<br />

In April 1992, the EU and US recognised the<br />

new state of Bosnia-Herzegovina. War broke out<br />

immediately, but the Serb-controlled army had<br />

confiscated the weapons of its territorial defence<br />

forces. Hundreds of thousands of Muslims were<br />

swept from their homes, especially along the Drina<br />

valley in the east of the country.<br />

During the next four years Bosnia would be torn<br />

by the bloodiest and most ruthless European conflict<br />

since the Second World War. The capital, Sarajevo,<br />

was the focus of an epic siege in which 12,000<br />

people were killed, including 1,600 children.<br />

The siege of Sarajevo began with Serbs raining<br />

shells on the city from hilltop positions.<br />

In August 1992, evidence emerged of Muslims<br />

in northern Bosnia being herded into concentration<br />

camps. These TV images led to the creation of a UN<br />

War Crimes Tribunal, now sitting in The Hague (the<br />

first international war crimes trial since Nuremberg).<br />

At the same time, the largest refugee movement<br />

in Europe since the Second World War began as<br />

Muslims fled to Croatia and other parts of Europe.<br />

‘That summer of 1992, only months after the<br />

Bosnian war erupted, was the darkest period in<br />

Europe since the Holocaust. In an orgy of murder,<br />

rape, detention, and eviction, the Serbs put<br />

hundreds of thousands of dispossessed Muslims to<br />

flight and seized their ancestral lands.’ Ian Traynor,<br />

The Guardian, 22 December 1994.<br />

By 1993 Serbs controlled almost two-thirds of<br />

Bosnia, while Croats had taken over nearly onethird.<br />

Evidence of massive human rights atrocities<br />

were discovered, including the raping of thousands<br />

of Muslim women and ‘ethnic cleansing’ actions by<br />

Serbs, especially in eastern Bosnia. In May 1993, the<br />

United Nations designated six UN-protected ‘safe<br />

areas’ in Bosnia. These were all areas that had been<br />

under siege by the Bosnian Serbs for some time and<br />

where Muslims were under threat: Sarajevo, Tuzla,<br />

Bihac, and three small enclaves in eastern Bosnia<br />

(Srebrenica, Gorazde, Zepa). UNPROFOR (UN<br />

Protection Force) soldiers provided limited military<br />

protection and humanitarian aid.<br />

In July <strong>1995</strong>, Serb forces launched attacks on the<br />

UN safe areas in eastern Bosnia, forcing thousands<br />

of Muslims from their homes in Srebrenica and<br />

Zepa, and ‘ethnically cleansing’ areas that had been<br />

Muslim for generations. The men were driven out<br />

of the ‘safe havens’—as the UN forces watched—to<br />

mass execution sites in the countryside around.<br />

In August <strong>1995</strong> shells launched from Serb<br />

positions in the surrounding hills landed in a<br />

marketplace in Sarajevo killing 85 people. NATO<br />

finally launched massive air strikes against Bosnian<br />

Serb positions.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

The Siege of Sarajevo<br />

26th October to 3rd December <strong>1995</strong><br />

In which the artist Dominic Ryan after returning to Australia meets again the<br />

Slovenian journalist, Darja Lebar. They decide to enter Sarajevo towards the end of the siege in<br />

october <strong>1995</strong> smuggling a humanitarian billboard carrying a message - we have all suffered<br />

enough into the city. After being temporarily arrested on the grounds of spying for the Serbians<br />

by inadvertently taking photos in a sensitive military area, with the help of the UNPROFOR<br />

French 4th battalion the two along with the French battalion erect the billboard in the destroyed<br />

House of Youth. Ryan is subsequently awarded the Liberty Prize for Human Rights in the EU. He<br />

returns to Australia. Forming a small voluntary group of friends who decide to continue to focus<br />

on conflict resolution in zones of war.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Cast of Characters:<br />

Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

DARJA LEBAR<br />

FUAD HADJHALOVIC<br />

DR JURASLAF KELLER<br />

OMER DELIC<br />

FATIMA DELIC<br />

BRANKO SERKOVIC<br />

ZOLKA or ZORAN<br />

MIRZA<br />

IGOR CAMO<br />

ALMIR VRPOIC<br />

ZJELKO<br />

NEVAN<br />

ENDIA<br />

RADGOVIC<br />

TAHIR GAMBIS<br />

ALMA SAHBAZ<br />

DAVID BALHAM<br />

DEBORAH<br />

SERGEANT MARCO ROYER<br />

CAPITAINE OLIVIER DEMENY<br />

Slovenian journalist and associate and guide for Dominic Ryan, Darja’s<br />

boyfriend, Ivo Standeker, died on June 17, 1992 in Sarajevo. Tanks and<br />

mortar shells from a Serbian position in Sarajevo injured Standeker,<br />

a journalist with the Slovenian magazine Mladina. Darja was a also<br />

wounded by sniper fire in Snipers’ alley<br />

Director of Gallery, ‘Collegium Artisticum’, Sarajevo<br />

Honorary Consul of Australia in Zagreb Croatia<br />

landlord of Dominic Ryan while sojourning in Sarajevo.<br />

Former Yugoslav Airline pilot<br />

wife of Omer Delic<br />

friend of Darja Lebar<br />

39-year-old photographer with magazine, SfeboneBosna<br />

ISCON Hare Krishna representative from Sarajevo<br />

composer of music for peace installation<br />

friend of Darja Lebar who subsequently became her husband<br />

friend of Almir<br />

tour guide and former paramilitary commander<br />

secretary at the Obala Centre for Art, Sarajevo<br />

musician, flautist and friend of Dominic Ryan<br />

cinematographer, human rights activist, who was making film Exile In<br />

Sarajevo at the time of ryan’s exhibition<br />

cinematographer and subsequently co-director on Exile In Sarajevo<br />

UNPROFOR radio and Public Relations Officer, Sarajevo<br />

Public Relations Officer at UNPROFOR<br />

UNPROFOR, Skenderija, French 4th battalion<br />

Public Information Officer, UNPROFOR, Skenderija, French 4th battalion

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

The Diary of Dominic Ryan: The Journal of Sarajevo<br />

26th October to 3rd December <strong>1995</strong><br />

The end is easy because a new<br />

chapter has just begun. After three years of siege<br />

the war in the Balkans has nearly ended. When it<br />

does end there will come an end to the countless<br />

slaughter of human beings. How I begin is perhaps<br />

more difficult. I did not come here to write this<br />

diary and I am not a journalist. I did not come here<br />

to make blood money, be a danger safari tourist or<br />

drink from the cup of destruction. But rather the<br />

Director of ‘Collegium Artisticum’, Fuad Hadjhalovic,<br />

who I had met in the Bosnian Embassy in Ljubljana<br />

had invited me to participate in the Winter Festival<br />

of Sarajevo.<br />

It is hard to trace the cause and origin of an<br />

event. We can return in our memories further<br />

into the past but always there is one point when a<br />

moment becomes destiny. That moment was the<br />

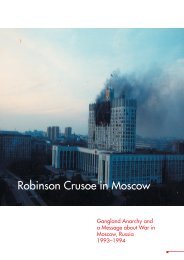

moment of the autumn of 1993 in Moscow, Russia. It<br />

was Perestroika, when Communism had fallen to be<br />

replaced by a rampant anarchy.<br />

I had moved to Moscow at the invitation of the<br />

Russian Federation of <strong>Peace</strong> and Conciliation with a<br />

large mural called Millennium.<br />

After my girlfriend Michelle and I had had<br />

our apartment guttered in a sudden blaze in the<br />

outskirts of industrial Moscow and our belongings<br />

left in charred ruins we were temporarily homeless.<br />

A chance meeting in a nightclub ‘Sexton Fondz’<br />

brought a journalist into our life. Her name was<br />

Darja Labar who was recuperating in Moscow that<br />

spring. Darja was a Slovenian journalist who had<br />

been wounded by a sniper in 1993 in the besieged<br />

city of Sarajevo. She had subsequently spent three<br />

months in a coma recuperating in the five-star Mayo<br />

Clinic in Minnesota USA.<br />

We had decided together to design a billboard<br />

based on my art. The text would read, ‘We have all<br />

suffered enough’. The next phase would be to bring<br />

this message into a city under siege. I realised that<br />

this mission was not only to communicate through<br />

art but also to reach out and to give innocent people<br />

who were suffering, the innocent victims of war, a<br />

voice to speak through global media.<br />

Sometimes when I am inside an event I never<br />

realise quite the import or exciting nature of what<br />

is around me. Surrounded by events that seem to<br />

be ultra-normal they are actually extraordinary.<br />

Therefore even before they were to occur I realised<br />

that they needed to be recorded for others to share<br />

our journey.<br />

Thursday, 26th October, <strong>1995</strong>,<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

So I am sitting half on the chair half on the<br />

billboard in a dimly lit brasserie in Ljubljana on<br />

a high backed cane chair. It is called ‘Rum and<br />

Cola’ and I have just arrived, exhausted, waiting

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

It is a quietness that I can’t quite put my finger on and perhaps<br />

is the proverbial calm before the raging storm. Darja looks as if<br />

she has grown with the years since I last saw her in Moscow—<br />

for the onset of jet lag like an aerial flu. Darja has<br />

only recently picked me up from the Ljubljana<br />

airport. 4.23 pm downtown temperature 8 degrees<br />

centigrade in the shade and I’m thinking this coat<br />

with its faux leather is ridiculous… It is a sombre,<br />

smoked and choked zero day, and the bustling life in<br />

the streets of this provincial Slovenian town seems<br />

as if it has been plucked out of a 1950s postcard<br />

and re-animated…. There’s a meandering river that<br />

slithers snake-like through the city centre, and<br />

suddenly it occurred that this is a Second Paris, but<br />

only Paris when it was back in the 1950s—tranquil,<br />

serene and effervescent.<br />

Boulevards of pedigree trees along shady<br />

riverbanks, sidewalk cafés and chic restaurants.<br />

There is quietness and stillness in the air. The<br />

pedestrians seem to move as if they have this<br />

stiffness in their legs.<br />

It is a quietness that I can’t quite put my finger<br />

on and perhaps is the proverbial calm before the<br />

raging storm. Darja looks as if she has grown with<br />

the years since I last saw her in Moscow—9 months<br />

ago exactly. A handsome strong women in her late<br />

twenties, with chestnut brown bobbed hair cut at<br />

the shoulders, a double breasted military leather<br />

style jacket, dark glasses and a generous slash of<br />

bright vermilion lipstick. Her bobbed hair is always<br />

cut in such a way that the bullet scars beneath her<br />

left eye are hidden.<br />

I had first encountered Darja Lebar in Moscow<br />

eighteen months prior with my Australian girlfriend<br />

Michelle in a first floor night club ‘Noche Noi Klub’<br />

deep in the heart of Moscow suburbia—a heavy<br />

metal nightclub, ‘Sexton Fonda’ with a rusted<br />

chicken wire cage to protect the band from the<br />

drunken audience throwing broken “Piva” bottles.<br />

Darja was originally a friend of Michelle’s at that time<br />

but after a succession of events catapulted the three<br />

of us into being together and, in some ways, I felt<br />

that a mysterious series of external circumstances<br />

were guiding us towards a new and ultimately better<br />

destiny. Every person I believe has a destiny or<br />

multiple destinies and my destiny with Darja is just<br />

one of those threads. It is not coincidence, it is not<br />

chance but an extraordinary fusion of fate with luck.<br />

Darja had been a reporter for the Slovenian<br />

journal Republika. Tanks and mortar shells from a<br />

Serbian position in Sarajevo killed Standeker, her<br />

boyfriend at the time, a journalist with the Slovenian<br />

magazine Mladina. Darja was also wounded by<br />

sniper fire in Snipers’ Alley three months later while<br />

covering the Sarajevo siege at its beginning while in<br />

the passenger seat of a taxi. A hollow point bullet<br />

had penetrated her cheekbone, narrowly missed her<br />

left eye and had moved down past her jaw shattering<br />

the jaw and the facial structure until it lodged itself<br />

at the base of her neck. Small fragments of shrapnel<br />

remained, undetected, lodged in her brain, which<br />

subsequently induced limited epileptic seizures.<br />

She had spent three months in a coma in the Mayo<br />

Clinic, a private clinic in Minnesota. When we met<br />

in Moscow she had only recently been released from<br />

the clinic to recuperate.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Darja is and was a remarkable woman—strong<br />

and almost military-like in a way that she walked<br />

and strode. She always wore one doubled breasted<br />

leather jacket covered in a patina of age. I think<br />

it had been bought in Moscow at one of those flea<br />

markets… Always burgundy trousers, never dresses<br />

and rarely makeup. Except today with that splash of<br />

lipstick… Our relationship is friend and colleague,<br />

but sometimes I feel it could be more, and she is<br />

here in Ljubljana now to assist me.<br />

As I look out across the square with its Parislike<br />

condiment, and the babbling of the River<br />

Ljubljana my mind keeps going back to Moscow<br />

… Even before this is to begin … how did I meet<br />

this women? where did it all begin…? I tell myself<br />

to trace it back<br />

Dominic, and<br />

maybe I can<br />

understand what<br />

model the future<br />

is going to present<br />

the two of us…<br />

In a Moscow of<br />

inflation, gangsters<br />

and a filthy metro,<br />

Michelle and my<br />

one bedroom<br />

apartment on the<br />

outskirts of the city had been burnt down.<br />

Guttered and divested of our possessions we<br />

were homeless… It was on my birthday, May 21,<br />

and the apartment was at the end of the metro<br />

line… Pragueshka, is the Metro zone at the end of<br />

the line in Moscow (in all senses I can assure this<br />

diary). It was a miniature cat-urine-smelling one<br />

bedroom apartment which felt like half-life cancer<br />

living there; I don’t know why. After returning from<br />

a celebratory birthday picnic at 4 in the afternoon,<br />

we discovered the apartment was obliterated by<br />

fire. Two wooden sticks of wood hammered as a<br />

cross had been nailed across the front door after the<br />

fire brigade had left. Seriosha, my mafia friend, had<br />

looked across at me, paused and then grinned from<br />

ear to ear and declared, ‘Happy Birthday, Dominic!’<br />

Destitute with nowhere to go, our first option was<br />

to billet at our friend’s, the Red Soviet artist, Pasha,<br />

studio. A cold water flat on the other side of Moscow<br />

at Filiovsky Park, he tolerated us for about three<br />

days, two hours and twelve seconds but, because he<br />

had to work at the studio, we were soon back in the<br />

spring cold, friendless and searching for new digs.<br />

But Darja, Michelle’s friend who was living with<br />

a Brazilian interior decorator at the time, soon<br />

befriended us, suggesting: ‘Come and stay with me.’<br />

We happily agreed.<br />

My memories of that time are of a chaotic<br />

Moscow, mud in the streets, pukh, a kind of blossom<br />

in the air, a clear fresh spring when we always<br />

played Sade’s ‘No Ordinary Love’. And here we<br />

lazed by the windowsills. Whenever I hear that song<br />

replayed, like Proust’s Madeleine, I spontaneously<br />

return to the nostalgic era when Darja, her Brazilian<br />

boyfriend, Michelle and I were sprawled in that<br />

apartment in the spring of 1994.<br />

We became as close as two couples can. But<br />

Darja had soon had her first epileptic seizure one<br />

evening when we were watching a Russian RTN<br />

television programme and I was visiting a friend in<br />

the street—Michelle saved her life, telephoning the<br />

ambulance and taking her to the ZILL hospital in the<br />

black of night. I was proud of Michelle that night.<br />

It was a strange, even curious time of endless<br />

departures and arrivals. After our sojourn with<br />

Darja we renovated the burnt-out flat and sadly<br />

returned there while Darja remained in Moscow.<br />

We eventually lost contact like a thread stretching<br />

until it broke. Six months later Michelle returned<br />

to Australia and, alone, trudging the weary<br />

Moscow boulevards one day in November 1994,<br />

I unexpectedly bumped into Darja in that same<br />

leather jacket on Novi Arbhat... We began talking<br />

effusively… We met two days later over espresso<br />

coffee and discussed the possibilities of taking a<br />

billboard—a facsimile of the painting Millennium<br />

and a humanitarian message—into Sarajevo. She<br />

thought it a<br />

good idea. It was<br />

inspiring and<br />

something we<br />

both felt we could<br />

achieve together.<br />

As I pen these<br />

memories a welltrained<br />

waiter<br />

has just bumped<br />

into me and my<br />

reverie is awoken.<br />

Yes, Darja is the<br />

catalyst for this journey. Even though my mind is<br />

focussed on Sarajevo as a gaol, it has arisen out of<br />

instinct and desire. But Darja gives me the strength<br />

and understanding that it is possible. The only<br />

person who knows the terrain, she can give me an<br />

added understanding of the geography, hurdles and<br />

challenges we are to encounter on the way. She<br />

speaks the language, and will be my guide, translator<br />

and mentor.<br />

Sunday, 29th October, <strong>1995</strong>, Slovenia<br />

We spend the today travelling to her family<br />

home which lies in some forested hills on the border<br />

with Austria, just outside Maribor. It is a small<br />

country house plucked irreverently out of a fairy

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

tale…I keeping I thinking the Brothers Grim or<br />

Goldie Locks is going to skip down the slate path<br />

towards me… The house, where she lives with her<br />

aged wrinkled parents, her two brothers and their<br />

children live, has been recently rebuilt after being<br />

burnt down. This abode is serene and tucked away.<br />

We occasionally listen to the radio and the news<br />

to monitor what is happening in Sarajevo. We have<br />

rung on a few occasions the UNPROFOR in Zagreb<br />

to discover if conditions on the ground are hostile or<br />

not. Currently there is a limited cease-fire between<br />

the Bosnian Serbs and the Muslims, which may<br />

allow us to safely travel across the demilitarised<br />

zone (DMZ) to reach the city of Sarajevo.<br />

A news report has flashed across CNN today,<br />

which is good. It reads:<br />

(CNN) -- The United Nations hopes opening<br />

the main road into Sarajevo will help life return<br />

to normal in Bosnia. Sunday, civilian buses,<br />

escorted by peacekeepers, made the first trip out<br />

of Sarajevo through Serb territory in more than<br />

three years. Only a fearless few turned up for the<br />

test ride.<br />

“I’m nervous. A little tense,” said one young<br />

woman, Emina.<br />

There were a dozen passengers and a<br />

dozen U.N. escort vehicles. Security was tight.<br />

Everyone was searched before boarding, and<br />

U.N. soldiers checked their strategy one last time<br />

before they left along the main road, straight<br />

through the Serb checkpoint.<br />

Darja’s idea is that we should visit the Embassy<br />

of Bosnia-Herzegovina tomorrow, which has<br />

been recently established in Ljubljana and sits in<br />

the southern sector of the city of Ljubljana. We<br />

also hope to travel there to be interviewed by<br />

the director of a gallery in Sarajevo, ‘Collegium<br />

Artisticum’ to see whether the gallery might be<br />

interested in exhibiting the billboard.<br />

Monday, 30th October, <strong>1995</strong>,<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

Bosnia-Herzegovina is now a new but separate<br />

nation-state with its representatives burrowed<br />

officiously here in this makeshift office Embassy<br />

in Ljubljana with bureaucrats zig-zagging across<br />

corridors holding sheaves of paper. The half light<br />

of the twisted shadows of the gnarled oak tree<br />

branches cast looming figures as oblique diagonals<br />

across the wide ebony desk in the Embassy Bosnia-<br />

Herzegovina as I rolled out the small image of the<br />

billboard to show the director of a museum in<br />

Sarajevo, Fuad Hadjhalovic. The Director of the

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

‘Collegium Artisticum’ is a round-faced fatherly man, with big glinting eyes that are kind, and embracing. It<br />

is wonderful when someone can be inspired by a message that you bring. It is not something that they see in<br />

terms of financial gain or economic viability. It is just simply the spirit of a message and they are taken up by<br />

that wave and they wish to surf it.<br />

In this era such events are so rare and I honour the people who can balance both the economics of their<br />

lives with courage and the pursuit of truth, justice, and love of the good.<br />

He is a thickset, burly man aged around of 55, but his appearance seems closer to the late sixties after the<br />

effects of a three-year siege and malnourishment—still ongoing in his hometown. Our spontaneous meeting<br />

as the result of a chance encounter with a mutual friend of Darja in the boulevard seemed fortuitous. Our<br />

meeting has occurred today at 3.36pm in the Bosnian Embassy in Ljubljana. Fuad likes the project immensely<br />

and with his bearish grin beams across the room at me. A smile is language enough that the project has been<br />

accepted. I manage to spread out the rolled up laminated image that is 20 centimetres across, as well as letters<br />

of introduction, as I explain the idea of bringing the forty-two by eleven foot image of war and peace entitled<br />

Millennium to Sarajevo. The words across it say: ‘We Have All Suffered Enough’.<br />

Also texts are in Serbo-Croatian, Bosnian and Russian.<br />

The director said: ‘Yes, Dominic, I like it, it appeals to my sensibilities, but my only concern is that words in<br />

Croatian and Serbian have to be excluded.’<br />

I am at a loss but this is one condition that I realise has to be accepted. My dilemma is whether nothing is<br />

to be done or something? My original concept is to bring the humanitarian message into the middle of the DMZ<br />

between the two sides, the Serbians and Bosnians. But what the people at the Embassy are saying now is: ‘No.’<br />

I realise they don’t want it there. It must come from their side and this is their message. As Fuad says: ‘We are<br />

the ones who have suffered enough.’ We left the meeting and now we must decide.<br />

In light of what is currently happening I agree but again I keep musing to myself—‘the message is neutral<br />

and its purpose is served by speaking to both sides.’ It is something akin to a neutral Red Cross message—<br />

humanitarian and speaks for the innocent on both sides of this conflict. But when people have suffered and

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

I can see below me not only the old<br />

and new city and the dappled almost<br />

medieval rooftops of Old Ljubljana and<br />

its surroundings, but also the moody<br />

marsh of Barje, and closer the green<br />

park Tivoli but also the Kamnik Alps in<br />

the north.<br />

have suffered at the hands of others they feel that<br />

they are the only victims (and in a sense they are<br />

predominately the victims even though acts have<br />

been perpetrated on Serbs), and the perspective<br />

is from that wound inside. Often it is a question of<br />

degree and sometimes injustice exists predominately<br />

on one side more than the other. So this is the<br />

dilemma I must face—either I present nothing or a<br />

slightly lopsided message. I must decide and yet I<br />

am pausing undecided as to what I must do.<br />

After a few hours here looking as a tourist from<br />

the Castle at the centre of the city I cast my eyes<br />

across the horizon thinking. The Castle, which<br />

is about a thousand years old, has been under<br />

reconstruction for quite a few years now, I can see<br />

below me not only the old and new city and the<br />

dappled almost medieval rooftops of Old Ljubljana<br />

and its surroundings, but also the moody marsh of<br />

Barje, and closer the green park Tivoli but also the<br />

Kamnik Alps in the north.<br />

Making my decision, I choose the latter,<br />

otherwise I must return with zilch. I will adjust the<br />

translations. Is it a compromise? Or a sell-out? I am<br />

not certain.<br />

And so, we, Darja and I mindlessly return to<br />

Maribor, another two and a half hours on the train<br />

with the locomotive’s rhythmic pulse rocking us into<br />

a Clockwork Orange reverie, while we brood, silent<br />

in our own separate worlds… This evening is serene;<br />

the high ravines topple past us on the train as the<br />

treacle golden sun is setting. After our arrival in<br />

Maribor as it is getting dark we roll out the billboard<br />

across the wet snow laden bitumen of the drive of<br />

her parents house across the garden patio …the<br />

dog sniffing it…maybe odours of Australia trapped<br />

in its creases. Racing with the fading light, using jet<br />

black paint I replace the Serbo-Croatian words with<br />

sticky white Letra-set images that keep being blown<br />

by the wind and those white Letra-set images simply<br />

say: ‘This is an image to the futility of war and its<br />

inability to solve the problems of humanity’.<br />

1st–4th November, <strong>1995</strong>, Maribor,<br />

Slovenia<br />

We spend a couple of days in the city of Maribor<br />

collecting fragments of white Letra-set, trying to<br />

arrange, like a jigsaw, all the letters correctly and<br />

laying it out in the sunshine, snatching moments<br />

when there is no rain or snow. Winter is encroaching<br />

and we have to be fast. I can feel it in my bones…<br />

The city of Maribor in the north of Slovenia is<br />

provincial and old world. The guidebook says that<br />

it is considered to be a cheerful, friendly city. Some<br />

relate this pleasant situation to its extensive winegrowing<br />

regions that routinely invite visits from<br />

Maribor residents. These vineyards are part of the<br />

natural beauty of the city, along with the Pohorje<br />

forests, the valley of the Drava river, the Kozjak<br />

and the Kobansko ravines, or the Slovenske Gorice<br />

hills and fields at the southeast of the city. But for<br />

me I can only feel the wind and sleet and my mind

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

is focussed on another city—Sarajevo where there<br />

are no guidebooks or tourists or souvenirs…the only<br />

souvenirs we will return with our memories and<br />

perhaps this diary.<br />

Each day, we religiously ring the United Nations<br />

and UNPROFOR in Zagreb for news and information<br />

on flights for incoming and outgoing personnel, but<br />

all the flights are booked out. There is no room for<br />

a grubby hippie-artist with long hair or a wounded<br />

Slovenian journalist. We are priority seven. Priority<br />

one is refugees and UN personnel. We are trying to<br />

get places in an airlift that will lift us into Sarajevo<br />

but it seems as if there are no possibilities. We are<br />

continuously hitting a brick wall. Bureaucratically<br />

they, the voices on the other end of the telephone,<br />

are polite and distant, but unhelpful.<br />

We are playing a waiting game, and the game<br />

is—we are waiting to go. Not knowing what to do we<br />

travel to a small town on the border of Austria, to kill<br />

time where Darja buys woollen jumpers while I am<br />

carrying my video camera, which I have rented.<br />

Sunday, 5th of November <strong>1995</strong><br />

The time is the time to rest… a meandering<br />

and sedate period…and leisurely visit to some<br />

lakes in the south of Slovenia…. Darja’s girlfriend<br />

who accompanies us seems like she has a feminist<br />

streak…even lesbian. Some of my best friends are,<br />

so it’s no insult but only a gentle observation. Her<br />

friends from the past are no exception. We drive<br />

with Darja with her friend to Lake Bohinj, twentyfour<br />

km south west of Bled. All her friends are<br />

strong, masculine women, not necessary lesbian,<br />

although Darja did recount to me a funny story<br />

about this woman who was absolutely infatuated<br />

by her. The woman was an American journalist<br />

stationed in Moscow in 1994. The two of them<br />

used to have these pretend romances and even<br />

orchestrated a mock wedding at her apartment,<br />

at which point they were going to really take the<br />

plunge as they say and get legally married. Darja<br />

towards the end of the finale of this clandestine<br />

pantomime backpedalled and said: ‘No!’<br />

Cold feet or a lack of enthusiasm. I recollect the<br />

budding bride was called Janet. Janet in any case<br />

was beside herself.<br />

At this point when Darja cancelled the wedding,<br />

she was due to return immediately to Slovenia.<br />

After boarding the plane at Shevimetizvo airport<br />

in Moscow the plane failed to take off. It was<br />

not allowed off the tarmac. The passengers sat<br />

dumbfounded for one hour and seemingly hostage to<br />

some security breach… a terrorist… a flu epidemic<br />

or an embargo? Darja was sitting in the aft end of<br />

plane when two sun glassed military personnel<br />

We are playing a waiting game, and the game is<br />

— we are waiting to go.<br />

strode on board. They declared to Darja ‘ There<br />

is someone outside waiting for you. We have been<br />

informed that it is a matter of life or death’<br />

Darja replied ‘What?’<br />

They said: ‘Can you please come with us?’<br />

She gets up. With all the other passengers<br />

staring blankly at her, there is Janet waiting at the<br />

steps of the plane pretending that she has an urgent<br />

life saving medicine that Darja had failed to take,<br />

and that without it, Darja would die.<br />

Darja looked at her: ‘What are you doing here?’<br />

Janet blushes coyly: ‘I just wanted to see you<br />

this one last time and this is the only way I could do<br />

it to say goodbye.’<br />

‘Great, okay, goodbye.’<br />

Darja had given Janet her telephone number and<br />

address in Ljubljana as she had an apartment there.<br />

Three weeks after Darja’s arrival in Ljubljana Janet<br />

appears at the front door. ‘Darja, its me. I‘m here’<br />

Again Darja was learning to exercise the word:<br />

‘Great’.<br />

Although she was a good host and Janet a great<br />

guest, a week later her uninvited guest had to leave<br />

unexpectedly. Janet was pregnant to an American<br />

she had slept with on a one night stand in Moscow.<br />

She decided over the toss of a coin to keep the child<br />

and return back to America. Darja’s obsessed fan<br />

disappeared overnight.<br />

Monday, 6th November, <strong>1995</strong>,<br />

Maribor, Zagreb<br />

Three days after our excursion to the Austrian<br />

border, the next journey will be spent by train<br />

travelling to Zagreb from Maribor. Zagreb will be<br />

an entirely different city. Compared with Zagreb in

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

Croatia, Slovenia has a tucked-away Swiss Toblerone<br />

chocolate feeling—a miniature country with hard<br />

working industrious people in track suits. But what<br />

it lacks in aesthetics it makes up for in hard work.<br />

An uneventful day filled with scribbled shopping<br />

lists written in smudged biro, chores and menial<br />

tasks. The errand at hand is to collect everything<br />

which we need for the journey: spanners, nylon<br />

rope, small supplies of food…Toblerone… aspirin,<br />

torch and batteries, cold winter jackets… bright<br />

ultramarine blue thermal underwear… old Slovenian<br />

socialist toothpaste with the cap stuck a kilter…<br />

boring but essential necessities. Once this has been<br />

completed the next is to conclude repairing the<br />

printed billboard. Finally after three hours and 23<br />

minutes with Darja and her stop watch and the dog<br />

sniffing both of<br />

us, the billboard is<br />

wrapped up into its<br />

own distinctive bag,<br />

curiously it appears<br />

like a filled body<br />

bag.<br />

There is a<br />

euphoric moment<br />

like an explosion<br />

of the present Now<br />

as Darja is standing<br />

beside me staring down at the huge image laid out<br />

across this impromptu tarmac, a MIG jet has left<br />

a smoke trail across the heavens above us like the<br />

signature of a giant, the golden sun is setting like<br />

treacle it is a naked and invigorating feeling.<br />

Tuesday, 7th November, <strong>1995</strong>, The<br />

journey to Zagreb, Croatia<br />

Even although I am the one with the intent,<br />

and the finances while Darja remains my loyal guide<br />

I know I am ultimately lost and adrift without her.<br />

I am troubled because I am taking her, Darja, back<br />

to Sarajevo, the place where she had been shot<br />

in the head… perhaps I muse our journey is like<br />

a time bomb…it will trigger memories and issues<br />

she cannot envisage but ultimately may help her<br />

too…or are we playing with fire…it is her decision...<br />

I look across at her yet she doesn’t know I’m gazing<br />

staring stealing a person’s image in my memory….<br />

Her mind-eyes-heart are elsewhere. At least I know<br />

that much… I don’t even believe she remembers the<br />

tragic and urgent last departure from that sad city.<br />

Thus her return will ultimately be very different.<br />

Each of us is travelling to meet our unknown that<br />

is disguised as fate or destiny or bank managers or<br />

bullets… and in her case she is returning to the past<br />

that had cut off a future she had believed would be<br />

trouble free.<br />

Perhaps this diary is more about Darja Lebar<br />

than Dominic Ryan. I was entering a zone of war<br />

with only a rented SONY hi 8 camera and few<br />

expectations. Darja was returning to the scene of the<br />

crime, which had left her disfigured and her future<br />

frozen in the past. By returning to face her demons<br />

Darja was attempting to heal the past. The city<br />

and the war had altered her destiny. Three months<br />

prior to the shooting she had been awarded the best<br />

journalist in Slovenia for her reportage from inside<br />

a city under siege. After being critically wounded<br />

by the sniper’s bullet she was returning for the first<br />

time to see the town, which had changed her life.<br />

Darja had lost her eye and still carried shrapnel in<br />

the neocortex of the her brain that could not be<br />

removed.<br />

There were moments of respite and calm before<br />

the storm. As the train travelled through the hills<br />

towards Zagreb I asked Darja:<br />

‘So how far do we have to go?’<br />

‘Far.’ She laughed…<br />

‘Why are we going to Zagreb?’<br />

She laughed with a bell chime to it… and<br />

squinted<br />

‘I think we have to talk about this. We have to<br />

have a very serious talk about this.’<br />

Our arrival is<br />

five hours later<br />

with weather<br />

conditions: light<br />

rain 2°C; westerly<br />

wind, 2 mph;<br />

relative humidity:<br />

96%; pressure<br />

(mB): 1027, rising<br />

visibility, fog<br />

And that was<br />

it…<br />

The idleness<br />

was soon to change and the seriousness of the<br />

journey set in. The area around Zagreb station is<br />

actually a grim and Celine-like, or at least it was<br />

tense that morning…. We decided to walk around<br />

and see what we could find, and shortly found a line<br />

of police roadblocks in the course of being set up.<br />

From what we could decide, these separated us from<br />

the old town, and there was nothing we could do<br />

about it because the police are only letting residents<br />

in.<br />

In Zagreb there are old winding mountain streets<br />

and genuine colourful markets. Nearby in the<br />

embassy district leafy boulevards stretch lazily, and<br />

beautiful elegant women in black leather jackets<br />

and red stripes of lipstick sip petit coffees. The city<br />

is clean, beautiful, not too large, and has an electric<br />

feel throughout it. Zagreb is a completely different<br />

world to the Europe I know. It is the ornate baroque

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

flourishes of the buildings, of the facades. The large<br />

tree-lined streets coupled with images and signs<br />

referring to bomb shelters and warnings as a result<br />

of the blitzes they have recently experienced.<br />

Upon our arrival, Zagreb was festooned with<br />

the perfume of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In<br />

Zagreb, when the streets are full with bustle and the<br />

knowledge that nearby a war is close—something<br />

that you can not tangibly touch. Inherent is the<br />

sense of pregnant anxiety, someone has swallowed a<br />

pill and they are waiting to feel its affects. The city<br />

was relatively benign and untouched by war. The<br />

journey had begun in cars, trains and buses, but<br />

the journey is more than travelling to the goal of an<br />

exhibition. It is also the places and the people we are<br />

to encounter during this journey.<br />

Since the United Nations proved a dead end,<br />

we had already discovered that there is one bus<br />

line that is ferrying people across to Sarajevo over<br />

300km away which had opened a few days ago.<br />

Economics prevails even in situations like this. So<br />

there are two things that we can do—find this small<br />

office in downtown Zagreb and buy a ticket. The<br />

office is shabby, down at heel; on the wall are faded<br />

photos of a gleaming by-gone Yugoslavia in National<br />

Geographic-green, scuffed and dog-eared. Old airline<br />

posters that are hanging at half-mast from the wall<br />

advertise the Greater and bygone Yugoslavia…<br />

Behind the formica desk, chain-smoking, there is<br />

a woman with bottle blond hair who has this long<br />

distance look about her as she puts the phone down,<br />

sucks on her cigarette and asks us whether it is a<br />

one-way ticket we want. We sit in a corner on the<br />

couches waiting and waiting. Finally they say there<br />

is a convoy leaving<br />

the day after<br />

tomorrow and it<br />

seems as if this is<br />

going to be the only<br />

option for us. We<br />

buy the ticket!<br />

The following<br />

evening we had<br />

a festive dinner<br />

with the honorary<br />

consul to Australia,<br />

Dr Keller and his<br />

Indian wife in the Hotel Dubrovnik. He spoke kindly<br />

to us. ‘You realise Dominic that you and your friend<br />

are travelling into a war zone. As a government<br />

representative I cannot forbid you to go; you are a<br />

free agent but as a representative of Australia I can<br />

only say that you will be essentially on your own. We<br />

cannot help you.’<br />

We sit there, attentive like puppets at the dinner<br />

table adjusting our serviettes like a businessman plays<br />

with his tie… Darja, his wife, Dr Keller and myself.<br />

I keep on thinking and laughing, it is like Keller,<br />

killer. It is the synchronicity of what is happening<br />

seems to sort of match everything. We speak of my<br />

Australian Bosnian friend, Tahir Gambis. He says: ‘Oh,<br />

I remember Tony Gambis, I had to visit him in hospital<br />

as he had been wounded by tank shrapnel during<br />

the war in the early stages and was lying in a hospital<br />

unable to return to Australia.’<br />

We were travelling into a zone where only<br />

accredited journalists and UN peacekeepers<br />

were permitted. In order to reach Sarajevo it<br />

was necessary to pass through six checkpoints.<br />

Documents or visas to enter Sarajevo or Bosnia were<br />

not required, yet the only civilians granted entry<br />

apart from the UN peacekeeping forces were the<br />

odd diplomat and now NATO.<br />

It is a journey into the centre of the darkness<br />

towards a distorted humanity. Each step towards<br />

this darkness is a step away from the light. I know<br />

such a journey will be difficult.<br />

These are strange days in the words of Jim<br />

Morrison of the Doors…surreal where again we walk<br />

through the streets surrounded by uncanny peace,<br />

laughing children, and surreal quietness. Anything<br />

except this is a future, which is unknown.<br />

Thursday, 9th November, <strong>1995</strong>,<br />

Zagreb, Croatia – Split<br />

As the day of departure arrives—what is so weird<br />

is that there are other people waiting to ascend the<br />

steps of the bus. We are not the only ones. I assume<br />

always incorrectly. Bonded families returning in<br />

spite of the imminent threat of death. We step onto<br />

the greasy linoleum aisles of the bus, dragging the<br />

billboard like a filled body bag. Nobody even blinks.<br />

Once seated, I gaze down from the dirty windows<br />

and I notice with solemn surprise everybody: the<br />

passengers—the overweight scarf-covered mothers,<br />

babuskas and young pimply men in denim and torn<br />

T-shirts are silently crying. The waving bystanders<br />

outside are crying, and the ones leaving inside are<br />

crying. Little old ladies with worn duffle bags, torn<br />

plastic sacks, teenage boys with metal buttons

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

They don’t know if they will die or whether<br />

they will see each other ever again.<br />

The roads are straight, and in one instance six hours<br />

into this journey late at night we come across a<br />

petrol tanker that had jack knifed in the centre of the<br />

highway…or something that was spun right across<br />

the road, blocking our path—<br />

Slowly through the<br />

dirty bus windows the<br />

landscape changes.<br />

and she has her own fears about the life that she had,<br />

a life that stopped after that bullet went into her face.<br />

In a sense she has to return to confront that reality

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

We are each entering a new world<br />

together but each of us is alone. Her<br />

eyes staring out into the passing<br />

countryside and even though she<br />

is accompanying me, it is almost<br />

as if only her physical body is<br />

accompanying me and she is returning<br />

to a place and a time and a life which<br />

I don’t have any connection to. I must<br />

realise and respect this—that I cannot<br />

share her sorrows or her life.<br />

implanted in their lips and Metallica T-shirts—and<br />

I realise that it is because of the unknown, because<br />

these people know that maybe they will not see<br />

each other again. For me it is a first, for them it is<br />

usual. They don’t know if they will die or whether<br />

they will see each other ever again.<br />

Every moment I use to try and draw out events,<br />

which have occurred, on this voyage. Then a diesel<br />

engine coughs slyly and jolts awake…<br />

Slowly through the dirty bus windows the<br />

landscape changes. Unhurriedly the world around<br />

us alters. Winter becomes more established even<br />

though we are travelling south. We have to travel<br />

a roundabout route: the bus travels from Zagreb<br />

down to Split and then up again over Mt Igman,<br />

which is where the one road to get to Sarajevo lies,<br />

past the tunnel that used to be, and then into the<br />

old city of Sarajevo.<br />

Darja and I sit in different seats. Dominic on<br />

this side of the aisle; she on the other. It is on this<br />

journey that I start to realise that Darja is distant.<br />

What a fool I am…of course…how stupid can I<br />

be in failing to understand the obvious… We are<br />

each entering a new world together but each of<br />

us is alone. Her eyes staring out into the passing<br />

countryside and even though she is accompanying<br />

me, it is almost as if only her physical body is<br />

accompanying me and she is returning to a place<br />

and a time and a life which I don’t have any<br />

connection to. I must realise and respect this—that<br />

I cannot share her sorrows or her life. Yes, there<br />

is our association but our association; she has her<br />

own demons to confront and she has her own fears<br />

about the life that she had, a life that stopped after<br />

that bullet went into her face. In a sense she has to<br />

return to confront that reality and to understand<br />

the impact it had on her being and on her destiny.<br />

She is brave and strong and maybe she has, like

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

One lonely heroic bus with a bald headed bus driver who speaks a<br />

language I don’t understand with the cold staring Bosnian civilians not<br />

speaking, not moving, not looking anywhere but into the empty passing<br />

countryside… lifeless trees and villages that have been recently shelled<br />

pass us by like ghosts trees and phantom villages.<br />

Oedipus, no choice but to be this way<br />

She is a million miles away but she sits two<br />

metres from me and I must accept that we have<br />

become distant partners on this twisting voyage<br />

towards Sarajevo.<br />

My thoughts rallied. ‘I am here to bring a 42’<br />

by 11’ image of war and peace to Sarajevo entitled<br />

Millennium but when I arrive, I know I cannot<br />

not bring myself to photograph these people. It<br />

will seem like stealing. To take and not to return.<br />

It is bad enough to take a people’s culture, even in<br />

images, when that is all they have, but to document<br />

suffering even when others have the need to have<br />

that suffering communicated is a difficult task. So I<br />

have chosen not to photograph the people. Out of<br />

awkwardness, shyness and an ethical point of view<br />

I instead will photograph the buildings. The way<br />

they had been destroyed by shells, the patterns and<br />

textures.<br />

The image is a large Christo-like poster, which<br />

I hope to be erected firstly in the House of Youth,<br />

or rather what is left of the House of Youth. The<br />

building has been bombed and reduced to rubble.<br />

As I understand it the building, Skenderija, is the<br />

equivalent of The World Trade Centre and Theatre<br />

complex. I am hoping that it Millennium will be<br />

shown in the streets of Sarajevo as a memorial and<br />

testament. The text reads: ‘this image is a mirror<br />

to the futility of war and its inability to solve the<br />

problems of humanity.’<br />

Thursday, 9th November, <strong>1995</strong>, Split,<br />

en route to Sarajevo<br />

It is 3.59 pm and we are travelling at 90<br />

kilometres an hour on the one lonely heroic bus with<br />

a bald headed bus driver who speaks a language<br />

I don’t understand with the cold staring Bosnian<br />

civilians not speaking, not moving, not looking<br />

anywhere but into the empty passing countryside…<br />

lifeless trees and villages that have been recently<br />

shelled pass us by like ghosts trees and phantom<br />

villages. While we are travelling into afternoon dusk<br />

and then the clumsy inky night…. eventually to our<br />

goal… pointing towards Sarajevo. The countryside<br />

passes us by in grey pastel snatches like someone<br />

handing out old tired postcards of Bavarian forests,<br />

which are taken away before you can see the full<br />

image. The roads are straight, and in one instance<br />

six hours into this journey late at night we come<br />

across a petrol tanker that had jack knifed in the<br />

centre of the highway…or something that was spun<br />

right across the road, blocking our path—an auto<br />

accident actually.<br />

Twenty minutes later into our trip we pass<br />

through villages which are just shells of rubble,<br />

broken with only one or two buildings that have<br />

any form of occupancy. Whole villages pass us by<br />

which are razed, with burnt, living rooms and empty<br />

windows. Like the eyes of the passengers so are

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

And the silence inside the cabin here<br />

is palpable… the silence amongst the<br />

passengers is deafening…<br />

the windows as we pass… It is a face that has been<br />

blinded. The houses are mere shells with nothing<br />

inside them. And the silence inside the cabin here<br />

is palpable… the silence amongst the passengers<br />

is deafening… Just as I’m getting used to this eerie<br />

silence the bus driver slips in a cassette…the music<br />

is worse… ranging from Croatian equivalents of<br />

Tom Jones crooning Croat hits from the past three<br />

decades to the euro-trash Abba.<br />

Each village has fifteen, twenty houses and in<br />

each village three quarters of the houses are left<br />

razed to the ground. It has emptiness, a fear and<br />

it was as if we have stepped into this fairyland and<br />

the whole land has been caged by an evil spell from<br />

a wicked warlock. A sickness has passed across the<br />

earth. None of us can avoid that sickness. And now<br />

the sickness is spreading to become part of us.<br />

My thoughts are alone and I gravitate back<br />

to Zagreb. Curious but our honorary consul Dr<br />

Keller had never been to Australia. He was the<br />

honorary consul but he had never visited Australia.<br />

It was as though he was an armchair traveller who<br />

geographically loved our country but had never<br />

visited. He is the representative of Australia out of<br />

his love for what it represented. He was not paid for<br />

his position and I honoured him for his voluntary<br />

nature of what he did. The buildings passed by,<br />

one by one—burnt-out desiccated shells like dead<br />

prehistoric animals with their rib cages showing.<br />

Split on the Adriatic coast—we arrive after<br />

twelve hours. A thirty-five minute stopover. We<br />

barely have time to urinate. Above our heads there is<br />

a black starless night while we are aching and tired.<br />

I slept sporadically backwards and forwards and<br />

have been reading a dog-eared book on the Turin<br />

shroud. Half read like an unfinished meal, it would<br />

remain undigested. Split is Croatia’s second largest<br />

city and it has a haphazard, hyper-electric ambience.<br />

It has a main street lined with derelict cafes facing<br />

the sea with a Roman palace behind it. I have heard

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

news that the western powers are making ideas to protect Split, in order to let the humanitarian aid coming<br />

in without problems. I have that feeling that nobody really knows what is going on. In Split, there is no war; in<br />

Split for months, only refugees.<br />

Here Darja takes me by the hand, almost tentatively like a child asking her father to come and see a new<br />

wild zoo animal… imploring me. ‘We must see this!’ To witness and view these incredible series of marble<br />

temples in Split. I suddenly realise as if I didn’t already know, that I am travelling. Moments of serendipity when<br />

suddenly we pinch ourselves and cry ‘my God!’<br />

It is a moment of inexplicable awe gazing at the Roman architecture with its patina of history and time like<br />

a singing aura. It is still and breathless. No wind…here but for the echoes of the footsteps on the marble tiles<br />

while boys and couples linger, kissing and giggling against Doric columns. There is moist warmth in the air<br />

maybe because we are further south. There is no snow. Spotlights illuminate the architecture and then I hear<br />

someone shouting to us to return quickly to the buses on the final leg of the journey—the journey towards<br />

Sarajevo.<br />

We travel into the night. I wake up and all I see is muddy walls surrounding us and lines of horrific broken<br />

barbwire. We stop for what seems two hours at a checkpoint. There are muffled voices of people who are<br />

speaking in languages I don’t understand. No passports are requested. Nobody cares; we are not passing<br />

through countries or across borders but rather into the dangerous unknown… We are stepping into a world of<br />

anarchy, suffering and injustice.<br />

Friday, 10th November, <strong>1995</strong>, Crossing over from Mt Igman into Sarajevo<br />

There are blurred mages of the charcoal night passing us, dashing spotlights blinding our eyes and then<br />

disappearing. More disturbing barbed wire and burst sand bags, and a half demolished tank appear. Upon<br />

awakening I notice that we are now in a convoy pushing slowly across Mt Igman. It is 7.00 am in the morning as<br />

the day dawns, I yawn myself awake. I feel greasy and unwashed like the windows. We pass a metal drop-gate<br />

in red and white like a barber’s pole. Here there is a rickety command post with stacked containers to create<br />

a wall, and camouflaged non-demarcated soldiers are squatting beside it mumbling into a walkie talkie—no<br />

insignias… I can’t tell if they are Serb or Muslim…just dirty stained khaki. One soldier gets in and sits with two<br />

oily Kalashnikovs on his knees and a thousand yard stare. Meanwhile these two personnel carriers, one at the<br />

front and one at the back escort the bus. An AA round will go through a hard metal chassis bus like a burning<br />

poker through margarine.<br />

Travelling at twenty-three kilometres an hour, the bus skips potholes, rolling like a ship in a force 8 gale, as<br />

we edge up and then down, in waving ribbons, along Mt Igman.<br />

As we descend the sausage-shaped mountain, the snow-sprinkled valley of Sarajevo becomes gradually<br />

apparent. Sarajevo is a city that sits in a fat bowl of a valley with a mountain range that completely surrounds<br />

it—a perfect circle of terror. It is the ideal position for an attacking force because the Serbian paramilitary have<br />

surrounded the besieged city which is trapped in the basin, a position most difficult to defend—and from an<br />

attacker’s perspective they can remain unseen indefinitely, their artillery punctuating the high ridge. A million<br />

shells have rained upon this one town. And for the people living here it is like being in a fishbowl and people<br />

killing fish for sport while a world looks on.<br />

Sarajevo lies at the bottom of this basin where the Bosnians lie under siege, and on the rim of the basin all<br />

these Serbians with tanks shelling the city. The former Yugoslav army and Serbian paramilitary have stationed<br />

themselves on this mountainside. On the outer perimeter of the city is the dead zone, where there are just<br />

burnt-out houses.<br />

Mt Igman had a thin covering of snow-like icing sugar. The bus drove down into the basin slowly, almost<br />

lazily with the convoy, as we went through the snow. It was the first snow since Split that I had seen. There is<br />

television up front on the bus, which is playing the most curious karate-style movies with Bosnian sub titles.<br />

Darja is asleep nodding with the roll of the bus into her scumbled leather jacket on the seat opposite<br />

me. So we drive through the suburb of Butmir, which has been all but destroyed by the fighting there. The<br />

first buildings as we enter the cities outskirts look haggard and run down. We pass the outskirts of the new<br />

embattled city where there are large brutalised housing commission buildings—a cheese grater has gone<br />

through them, slicing them up indiscriminately.<br />

Sarajevo is not a simple city. It has been documented and yet not observed enough. Battalions of journalists<br />

have descended upon Sarajevo like vultures to a dying animal to document its suffering, its massacres, and<br />

then, taking their spoils of war, they leave. I wonder if I am any better? Did they give anything of themselves to<br />

these people? To live off the sufferings of others I cannot do. I am not so sure now how I can help the suffering

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

of others with this image and project, but at the very least I am not seeking to exploit or profit from it.<br />

We soon leave the Muslim suburb of Dobrina which has been destroyed - with only the shells of houses<br />

remaining. Only 50 meters away, the Serb forces are poised in their positions, with their AA guns, which fall<br />

under the limit set by the heavy weapons exclusion zone.<br />

We pass across the airport tarmac and into Doboj, but we must wait 35 minutes before we are waved<br />

through. There is safe passage. Doboj has already been destroyed by the Serbs. These were apartment blocks<br />

built for the Olympics. We passed a large wall of destroyed automobiles, vans and buses which had been formed<br />

like bricks as sniper shields.<br />

We finally turned onto Snipers’ Alley which runs from Sarajevo’s suburbs into the centre of town. In 1992 a<br />

car could drive this road at 120 kilometres an hour but today we were slower and there was limited pedestrian<br />

traffic.<br />

After our arrival my first feelings are of numbness across the knuckles. I am hauling the billboard in the bag<br />

on the rollers through the snow-covered ice, slipping and sliding. Swearing castrated oaths under my breath,<br />

Darja striding ahead going from hotel to hotel. Darja marching with this military step and me in pursuit. We go<br />

to the Hotel Bosnia but its achingly too expensive or simply overpriced… Hotel Grands, then Europa Garni are<br />

closed… everything is closed up except the Holiday Inn… INFAMOUS DURING THE SEIGE… but we don’t<br />

have the finances… We are not CNN…<br />

As I walk into the disused foyer of the Holiday Inn I notice that none of the lights are on even in the early<br />

morning.The hotel was built for the Olympics in 1984 but right now it looks like the victims as paraplegics are<br />

having their own conference and nobody is winning… Half the side of the building is completely shattered<br />

while there remain a few dispossessed people, a lost concierge and a lone businessman at the back. The Inn is<br />

in the area of Snipers’ Alley, which has been the most vulnerable area in the city on a large square. I can see<br />

around me shrapnel-scarred housing commission blocks where people have turned nature strips into vegetable<br />

gardens, but all the vegetable gardens are now dead and the odd turnip or cabbage sticking through the thick<br />

black rich soil speckled by the snow.<br />

The sound is a listless stillness; it encroaches on us. After the Holiday Inn where it looks like there is no<br />

possibility of staying we move onto another hotel closer to the old part of the city. Here there are yet again no<br />

further possibilities either. It seems to be too expensive.<br />

Darja finds someone outside of the hotel who indicates with some sophisticated sign language that there is a<br />

couple, an old airline pilot and his wife, who can offer us full accommodation. We trudge again in order to find a<br />

taxi. Everything around us is dirty and run down. I’m still swearing under my breath. I need sleep and food and I<br />

know I won’t be served with either immediately… The dirt, the grease, the greyness; it is not even grey; it is like<br />

the difference between a clean tooth and a tooth that is dirty and a tooth that is rotting and it is like everything<br />

here looks like it is rotting. The siege has been going on and it is right at the end of the war but there is quietness<br />

as a result of the cease-fire. We believe there is an accord which is going to happen in the next two or three weeks<br />

to resolve the conflict but we are waiting on all parties to resolve the demarcation of the borders.<br />

The couple’s names are Fatima and Omer Delic. He is a retired airline pilot. The address is, so I don’t forget:<br />

440115 Autuno Brauna, Fourth Floor, Sarajevo. The 440115 is actually their telephone number. I must write it<br />

down and slip it into my shoe so if I get lost I’ll be OK.<br />

Fifth-floor apartment, three levels as we climb in nauseating spirals on the baroque Austro-Hungarian<br />

staircase with blown out windows on the east side and an acute smell of cat urine in the stairwell which<br />

after Moscow feels like home… There is no hot water and we have to boil the water. I can hear Rasta music<br />

somewhere. How curious! There is no electricity and no windows, just plastic UNHCR sheeting. It is ice cold<br />

and the water and foodhas to be carried up four stinking flights of stairs like a masochist gym in New York. And<br />

the food, if you could call it food, are basic necessities like potatoes.<br />

Saturday, 11th November, <strong>1995</strong>, Sarajevo<br />

At the height of the war a packet of Marlboro cost twenty-five dollars. Darja tells me that the Serbs still hold<br />

all the high ground around the city and have replaced their heavy weapons with AA guns. Firing 75mm rounds,<br />

which lie under the limit, these weapons can do as much damage as a mortar can. There are now specific zones<br />

of the city, out of the line of sight, which are safe. The Serbs have not surrendered all their heavy artillery to<br />

the UN, since they are still using some of them, to fire upon the eastern part of the city. Therefore this is a<br />

memo that no person is ever really safe here. The local cigarettes, Drina, which are manufactured in the city,<br />

are still being sold. It seems that everybody here smokes. The one initial thing that I have noticed, even though<br />

I don’t smoke or drink alcohol, is that here the people’s past time, or their way of dealing with this situation is to<br />

smoke. Every single person chain-smokes the local Drina.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

disaffected artist coming in to appease his<br />

own western guilt; a do-gooder or whether<br />

something is literally going...<br />

They just sit there and<br />

stare back at me, smiling<br />

through their gums<br />

always wearing their<br />

double pyjamas and<br />

dressing gowns as if the<br />

Sarajevo siege is some<br />

kind of pyjama party out<br />

of Monty Python but its<br />

just that …this is the best<br />

clothes to keep warm.<br />

If Picasso painted Guernica and brought this image into an<br />

environment where there was a war happening, the image<br />

of Guernica in this huge bombed out environment would be<br />

a potent image.<br />

What the fuck am I doing here? I really don’t know. I am following the scent or the actual points of bringing<br />

a message to people about suffering, and I just question whether I actually am doing something legitimate—for<br />

myself or for them. It is a weird environment to be in. I question whether this is just some weak and limp,<br />

disaffected artist coming in to appease his own western guilt; a do-gooder or whether something is literally<br />

going to come out of this. I know when the intent is right then good things occur of their own volition even if we<br />

see difficult events surrounding them.

M I N U T E S T O WA R : Once Upon a Time in Sarajevo<br />

This is a symbolic act, and the act is to take the billboard into<br />

an area where the context is meaningful—that we are putting a<br />

message about war and the futility of war and we are taking it<br />

into an area where there really is war.<br />

Sunday, 12th November, <strong>1995</strong>,<br />

Sarajevo<br />

Inside the socialist-style apartment Omer proudly<br />

shows me a framed photo of him arm in arm with<br />

Tito standing at a school reunion in a sepia tone. An<br />

image of him meeting God almost. Omer with Tito!<br />

Omer and Fatima have a set of cheap Yugoslavianera<br />

spoons on the mantle piece proclaiming the<br />

winter Olympics… old communists that have been<br />

hoisted up by the war and are about to be propelled<br />

into a new period but because they are almost<br />

unwilling they are still frozen in the old era.<br />

The only way I can speak or communicate with<br />

them is with my broken Russian, which does not<br />

seem to help much but at least it is a kind of a<br />

buffer. We sit down for breakfast. They just sit there<br />

and stare back at me, smiling through their gums<br />

always wearing their double pyjamas and dressing<br />

gowns as if the Sarajevo siege is some kind of pyjama<br />

party out of Monty Python but its just that… this is<br />

the best clothes to keep warm.<br />

I am still questioning my motives for coming. I<br />

am questioning why I am here, but in the process<br />

there is human contact and this is nothing about<br />

questioning, it is just human beings bridging the<br />

gap between their isolation, their loneliness, their<br />

insecurity. It is goodwill that is the better angel<br />

within us and whatever the case, it is a step where<br />

we find out what good can come out of a difficult<br />

situation.<br />

This is a symbolic act, and the act is to take<br />

the billboard into an area where the context is<br />

meaningful—that we are putting a message about<br />

war and the futility of war and we are taking it into<br />

an area where there really is war.<br />

If Picasso painted Guernica and brought this<br />

image into an environment where there was a war<br />

happening, the image of Guernica in this huge<br />

bombed out environment would be a potent image.<br />

So it can be argued Millennium takes art into a new<br />

area. It is an attempt to extend the boundaries of art<br />

to create a form of diplomacy. It is crossing areas:<br />

diplomacy, art, politics, humanism, but also none of<br />

the above but all of the above simultaneously.<br />

Looking around their kitchen I muse: it is<br />

interesting how the war created all these new<br />

industries. All of a sudden there was no electricity<br />

and the situation was one where they had to create<br />