Download - Voice Male Magazine

Download - Voice Male Magazine

Download - Voice Male Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

By Rob Okun<br />

Iam at a point in my life where I welcome<br />

my tears. It wasn’t always that way.<br />

Despite the work I’ve done on myself—<br />

and the work I do—sometimes it still feels<br />

unsafe to let tears come. Other times I don’t<br />

have any choice.<br />

Such was the case on a snowy December<br />

night when I was in the audience listening<br />

to David Mallett, a remarkable singer-songwriter<br />

who I first heard when I was around<br />

30. This year, I turn 60. Throughout my thirties,<br />

forties and fifties, listening to David’s<br />

salty, seasoned Maine baritone would always<br />

tear a piece of my heart. His voice does for<br />

me as a middle-aged man what Janis Joplin’s<br />

plaintive siren’s call evoked when I was in<br />

my twenties. In his voice, all the more rich<br />

with age, his songs burrow in, massaging<br />

my heart.<br />

More men than you’d think are like<br />

David Mallett, sharing stories from our<br />

hearts. His tales of lost love, hurting, healing,<br />

and redemption are our stories, too. Listening<br />

to him that wintry night it felt as if he was<br />

making me an offering: “Here. Take these<br />

songs as a gift, man to man.”<br />

Some of the music turned over—like<br />

clumps of rocky earth—broken pieces of<br />

my heart. Missing my father, gone since<br />

’88. Wounds from the end of a marriage<br />

two decades ago (healed over as much as<br />

those kinds of wounds can). Out of the<br />

shards of loss I’ve made myself whole, and<br />

I felt a brightness, too, in jaunty tunes of<br />

celebration of nature—both human and in<br />

the environment. They evoked in me a quiet<br />

contentment—my heart opened wider than<br />

ever, appreciating the great joy of a loving<br />

wife and the blessing of four amazing adult<br />

children.<br />

In my travels to conferences and from<br />

my perch editing this magazine, I sense more<br />

men are starting in earlier to take inventory<br />

of our lives, to more readily share what we<br />

find. Few of us have a stage to stand on like<br />

David Mallett, yet we’re more alike than<br />

different—guys who have been around the<br />

block, lines in our faces and, like the bard,<br />

2 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

FROM THE EDITOR<br />

Listening for the Harmony<br />

in Our lives<br />

Singer-songwriter<br />

David Mallett<br />

weathered like the Maine coast. We can<br />

hear in his voice—a harmony of strength<br />

and gentleness—our own lyrics, wisdom<br />

blending with melodies that turn song into<br />

poetry. We may not have his gifts as a poet,<br />

yet we can tap into the same well of tenderness.<br />

On that Sunday night at the dark of the<br />

year, he was our balladeer playing more<br />

than two dozen originals, songs that mapped<br />

the human heart. One, called “Beautiful,”<br />

professed love for his daughter. He sang,<br />

“You are one of a kind/a wild flower on<br />

the vine/and the whole world’s waitin’ for<br />

you/cause you are the most beautiful girl/<br />

you are the wonder in my life/you don’t<br />

know but its true/I’m forever lovin’ you/<br />

I’m forever lovin’ you…” His love for, and<br />

appreciation of, his father was expressed in<br />

“My Old Man.” In it Mallett sang, “My old<br />

man/Talkin’ about my old man/He was there<br />

at the start with a willin’ heart/He was there<br />

when the world began/My old man was a<br />

daddy/ Till I got too cool to call him that<br />

any more/He took my momma to the grange<br />

hall dance/And he waltzed her across the<br />

floor…/My old man, talkin’ about my old<br />

man/ talkin’ about my old man…”<br />

Like the gentle side of most men, David<br />

Mallett’s tenderness might have been<br />

obscured if I’d only skimmed the surface—<br />

seeing in him only a road-weary troubadour,<br />

hard and stoic. How sad it would have been<br />

to have missed the truths he was sharing,<br />

just as it’s sad that too many of our vulnerabilities<br />

and longings as men are overlooked.<br />

Skimming the surface is what the culture<br />

often does with men, missing an opportunity<br />

to plumb our depths. For the mainstream<br />

media and popular culture, men are usually<br />

seen as uncomplicated beings living in the<br />

now, without histories, moving on with few<br />

regrets. We’re just after the big deal, the<br />

quick fix, or the quickie. It’s not so. The next<br />

time you find yourself—or hear someone<br />

else—describing men simplistically—think<br />

about the men you know, men like David<br />

Mallett, whose lives are made up of tenderness<br />

and tears, joys and sorrows, strengths<br />

and vulnerabilities. We may not all be songwriters<br />

and poets but each of our lives is the<br />

stuff of songs and poems. Listen between the<br />

lines every day to tap into that truth.<br />

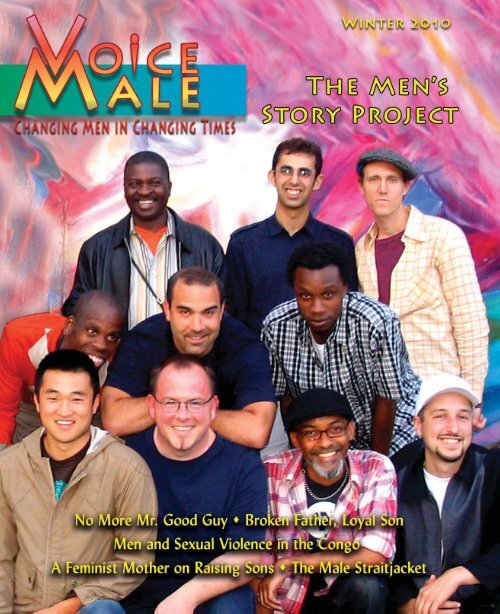

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> readers will no doubt be<br />

interested in two examples of men sharing<br />

our truths more publicly. The Men’s Story<br />

Project (our cover story, beginning on page<br />

18) is a powerful dramatic expression of men<br />

speaking honestly from their inner lives. And<br />

V-Men, a kind of men’s auxiliary of V-Day,<br />

the international effort to prevent violence<br />

against women and girls, is beginning to<br />

hold workshops as part of an effort to create<br />

a new dramatic presentation entitled Ten<br />

Ways to Be a Man. (See back cover.) The<br />

possibilities for this next decade being one<br />

where more men share the truth of our lives<br />

will only grow stronger if more of us are<br />

willing to leave the man caves of solitude for<br />

the gardens of our hearts.<br />

Rob Okun can be reached at rob@voicemalemagazine.org.

www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

Features<br />

10<br />

14<br />

16<br />

18<br />

23<br />

27<br />

Columns & Opinion<br />

2<br />

4<br />

5<br />

8<br />

12<br />

25<br />

29<br />

30<br />

31<br />

32<br />

No More Mr. Good Guy?<br />

Stepping Off the Pedestal of <strong>Male</strong> Privilege<br />

By Tal Peretz<br />

Invisible Men<br />

Men, the Mainstream Press and Rape in the Congo<br />

By Jackson Katz<br />

Is It Anger or Is It Abuse?<br />

By Joyce and Barry Vissell<br />

Men’s Lives, Men’s Truths<br />

The Men’s Story Project<br />

By Charles Knight<br />

A Feminist Mother on Raising Sons<br />

By Sarah Epstein<br />

From the Editor<br />

Letters<br />

Men @ Work<br />

Outlines<br />

Fathers & Sons<br />

Men and Health<br />

Men Overcoming<br />

Violence<br />

Books<br />

Film<br />

Resources<br />

Winter 2010<br />

Changing Men in Changing Times<br />

Imagining a Different World to Understand This One<br />

Through the Looking Glass of Violence<br />

By Stephen McArthur<br />

Listening for the Harmony in Our Lives By Rob Okun<br />

The <strong>Male</strong> Straitjacket By Brendan Tapley<br />

Broken Father, Loyal Son By John Sheldon<br />

Men at Greater Risk For Cancer Death?<br />

Why Men Can’t Remain Silent By Byron Hurt<br />

8<br />

14<br />

18<br />

23<br />

Winter 2010 3

www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

Rob A. Okun<br />

Editor<br />

Lahri Bond<br />

Art Director<br />

Michael Burke<br />

Copy Editor<br />

National Advisory Board<br />

Juan Carlos Areán<br />

Family Violence Prevention Fund<br />

John Badalament<br />

All Men Are Sons<br />

Eve Ensler<br />

V-Day<br />

Byron Hurt<br />

God Bless the Child Productions<br />

Robert Jensen<br />

Prof. of Journalism Univ. of Texas<br />

Sut Jhally<br />

Media Education Foundation<br />

Bill T. Jones<br />

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Co.<br />

Jackson Katz<br />

Mentors in Violence Prevention Strategies<br />

Michael Kaufman<br />

White Ribbon Campaign<br />

Joe Kelly<br />

Th e Dad Man<br />

Michael Kimmel<br />

Prof. of Sociology SUNY Stony Brook<br />

Charles Knight<br />

Other & Beyond Real Men.<br />

Don McPherson<br />

Mentors in Violence Prevention<br />

Mike Messner<br />

Prof. of Sociology Univ. of So. California<br />

Craig Norberg-Bohm<br />

Men’s Initiative for Jane Doe<br />

Chris Rabb<br />

Afro-Netizen<br />

Haji Shearer<br />

Massachusetts Children’s Trust Fund<br />

Shira Tarrant<br />

Prof. of Gender Studies Cal State<br />

Long Beach<br />

4 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

Mail Bonding<br />

Facing Our Fragmented Selves:<br />

Cracks in Patriarchy<br />

I appreciate the personal, world and culturespanning<br />

perspective you shared in [“From the<br />

Editor,” Summer 2009]. Never a fan of either<br />

subject of your piece [Michael Jackson and<br />

Ayatollah Sayed Ali Khamenei], they do represent<br />

a reflection of our broad-spectrumed masculinity<br />

and so [are] a reflection of myself. Along with<br />

the other examples mentioned from the political<br />

arena that show the usual face of patriarchy<br />

(wounded and unhealthy masculinity),<br />

it speaks to the split within<br />

ourselves from the failure to face<br />

and integrate the shadow. Our fragmented<br />

selves can only act out in<br />

wounded ways when the shadow is<br />

unacknowledged and unintegrated.<br />

For the patriarchal expressions you<br />

cite, the word of caution to each<br />

of us is that we do well to look at<br />

ourselves in the mirror for what we<br />

see looking back. More personally, I<br />

need to continue to look to see what<br />

am I doing to heal the effects of the<br />

fragmented masculine paradigm I’ve<br />

been nurtured in, to ask what concepts inform my<br />

way of being a man, what actions will I pursue to<br />

be a wedge in that widening crack of the patriarchal<br />

plague that feeds the violence in our world?<br />

Thanks for getting us all to stand in front of the<br />

mirror, the primary place of transformation.<br />

Mark Chaffin<br />

Schenectady Stand Up Guys, Schenectady, N.Y.<br />

www.schenectadystandupguys.org<br />

VM Needs to Reach Mainstream<br />

I found out about <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> last April at the Men<br />

Can Stop Rape conference in Washington, D.C.<br />

This is exactly the type of magazine we need to get<br />

out into mainstream newsstands and bookstores to<br />

replace the crap that’s currently available to men.<br />

I will pass along the link to the folks on my grad<br />

student listserv, as some of them study gender<br />

issues/masculinity. It’s a great resource.<br />

Mahri Irvine<br />

Department of Anthropology<br />

American University, Washington, D.C.<br />

Thai T-Shirt Not a Joke<br />

Editor’s Note: Below is a letter sent to The Onion<br />

in response to an ad published in the humor<br />

magazine.<br />

I am writing to request that you stop sales<br />

of your t-shirt referring to a friend who went to<br />

Thailand and “all he brought back was a kidnapped<br />

prostitute.” I’m not sure you understand how<br />

often women are kidnapped and sexually trafficked<br />

both internationally and domestically. The<br />

fact book from the University of Rhode Island<br />

on the Global Sexual Exploitation<br />

in Thailand* (www.uri.edu/artsci/<br />

wms/hughes/thailand) can provide<br />

you with information regarding the<br />

enormity of the problem and the<br />

scale of human suffering involved.<br />

I am sure after you have spent even<br />

10 minutes looking at this material<br />

that you will agree that a t-shirt of<br />

this kind only serves the purposes<br />

of the traffickers, pimps and slave<br />

traders by dismissing their cruelty<br />

as laughable. I’m sure that was not<br />

your original intent. I would also<br />

encourage you to develop policies<br />

regarding the sale of material that dismisses or<br />

condones the sexual exploitation of women and<br />

children.<br />

Chuck Derry<br />

Minnesota Men’s Action Network,<br />

Gender Violence Institute, Clearwater, Minn.<br />

* Around 80,000 women and children have been<br />

sold into Thailand’s sex industry since 1990, with<br />

most coming from Burma, China’s Yunan province,<br />

and Laos. Trafficked children were also found on<br />

construction sites and in sweatshops. In 1996,<br />

almost 200,000 foreign children, mostly boys from<br />

Burma, Laos, and Cambodia, were thought to be<br />

working in Thailand.<br />

Letters may be sent via email to www.<br />

voicemalemagazine.org or mailed to<br />

Editors: <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>, 33 Gray Street,<br />

Amherst, MA 01002.<br />

VOICE MALE is published quarterly by the Alliance for Changing Men, 33 Gray St., Amherst, MA<br />

01002. It is mailed to subscribers in the U.S., Canada, and overseas and is distributed at select locations<br />

around the country and to conferences, universities, colleges and secondary schools, and among<br />

non-profit and non-governmental organizations. The opinions expressed in <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> are those of its<br />

writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the advisors or staff of the magazine, or its sponsor,<br />

Family Diversity Projects. Copyright © 2010 Alliance for Changing Men/<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> magazine.<br />

Subscriptions: 4 issues-$24. 8 issues-$40. For bulk orders, go to voicemalemagazine.org or call <strong>Voice</strong><br />

<strong>Male</strong> at 413.687-8171.<br />

Advertising: For advertising rates and deadlines, go to voicemalemagazine.org or call <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

413.687-8171.<br />

Submissions: The editors welcome letters, articles, news items, reviews, story ideas and queries, and<br />

information about events of interest. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcomed but the editors cannot<br />

be responsible for their loss or return. Manuscripts and queries may be sent via email to www.voicemalemagazine.org<br />

or mailed to Editors: <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>, 33 Gray St., Amherst, MA 01002.

Are Glasgow’s<br />

Youth Soft on<br />

Men’s Violence?<br />

A study in Scotland reveals that<br />

young people have a high tolerance<br />

of violence and abuse if committed<br />

within an interpersonal heterosexual<br />

relationship. In an article in Men and<br />

Masculinities (Vol. 11, No. 3), “Justifications<br />

and Contradictions: Understanding<br />

Young People’s Views<br />

of Domestic Abuse,” Melanie J. Mc-<br />

Carry drew on empirical data from a<br />

school-based study conducted with<br />

77 young people in Glasgow that<br />

explored young people’s opinions<br />

of abuse and violence in interpersonal<br />

heterosexual relationships. A<br />

central finding is that there is profound<br />

contradiction in the views of<br />

the young people regarding what<br />

is interpersonal violence and about<br />

who is doing what to whom. The<br />

young people in the study were ambivalent<br />

about acknowledging the<br />

predominance of men as perpetrators<br />

of interpersonal violence, and<br />

where they did acknowledge males<br />

they constructed numerous justifications<br />

to explain it. Beyond simply<br />

presenting the findings, McCarry’s<br />

article explores reasons why the<br />

young people both resisted accepting<br />

men as perpetrators of interpersonal<br />

violence and tried to justify<br />

their behavior. To learn more, go to<br />

http://jmm.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/11/3/325.<br />

Network Challenges<br />

Hotel Pornography<br />

A men’s network in Minnesota<br />

is spearheading efforts to curb sexually<br />

violent and degrading material<br />

in public places with a current focus<br />

on hotel room porn.<br />

The Minnesota Men’s Action<br />

Network: Alliance to Prevent<br />

Sexual and Domestic Violence has<br />

drafted the anti-porn in hotels initiative<br />

with the Minnesota Department<br />

of Health’s Sexual Violence Prevention<br />

Program. The effort, according<br />

to Chuck Derry of the Gender Violence<br />

Institute, where the Men’s Action<br />

Network is located, “is part of a<br />

growing primary prevention plan to<br />

stem sexually violent and degrading<br />

material becoming accessible and<br />

mainstreamed into our social environment.”<br />

The Clean Hotel Initiative encourages<br />

business, public and private<br />

organizations, and municipalities<br />

to modify their meeting facility<br />

policy to clarify that meetings and<br />

conferences only will be held in<br />

facilities that do not offer in-room<br />

adult pay-per-view pornography.<br />

Additionally, Derry says, the recommendation<br />

calls for travel policies to<br />

be amended to reimburse employees’<br />

lodging costs only when staying<br />

at hotels that do not offer the inroom<br />

adult pay-per-view porn.<br />

Men’s Resource Center: Beginning Again<br />

We live in a time of upheaval<br />

and transformation, in which<br />

people all over the world are<br />

defining, questioning, and<br />

redefining their sense of identity—national,<br />

ethnic, racial,<br />

religious/spiritual, political, familial, sexual, and personal. .<br />

. The shift in thinking, feeling, and behavior experienced by a<br />

growing number of men is one expression of this widespread<br />

metamorphosis. Men no longer need to feel confined by definitions<br />

of maleness that value domination and violence, nor need<br />

they feel threatened by women’s struggle for equality. We can<br />

embrace both non-violence and liberation as we define ourselves<br />

in ways that allow our full development as human beings. We are<br />

committed to helping bring about a more just and peaceful world<br />

by redefining masculinity to exclude violence and embrace trust<br />

and compassion.<br />

—From the vision statement of the<br />

Men’s Resource Center for Change<br />

Like many non-profit social change organizations facing<br />

challenging financial realities, the Men’s Resource Center for<br />

Change (MRC), one of the oldest men’s centers in the U.S., is<br />

re-envisioning its role. The MRC, which traces its origins back<br />

27 years, recently took steps to help ensure the organization’s<br />

future in the face of current economic uncertainties. Much<br />

admired, the MRC has twin aims: “supporting men and chal-<br />

Men @ Work<br />

The Men’s Action Network has<br />

created several documents that can<br />

assist others interested in developing<br />

policies at state and local levels<br />

of government, as well as with private<br />

businesses, organizations, and<br />

agencies.<br />

To learn more go to http://www.<br />

menaspeacemakers.org/programs/<br />

mnman/hotels.<br />

Eat Soy, Stay Virile<br />

Soy foods don’t decrease testosterone<br />

levels. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger<br />

can now join President<br />

Barack Obama chowing down on a<br />

tofu-veggie stir fry.<br />

A new study published by the<br />

American Society for Reproductive<br />

Medicine finds that soy foods<br />

and soy isoflavone supplements<br />

have no significant effect on male<br />

reproductive hormone levels. Findings<br />

recently published online in<br />

Fertility and Sterility, a publication<br />

of the American Society for Reproductive<br />

Medicine, demonstrate no<br />

[continued on page 6]<br />

lenging men’s violence.” Among<br />

its many pioneering efforts were<br />

support groups for men with a<br />

range of experiences, a young<br />

men of color group, high school<br />

education, and free groups for<br />

women. (The center also launched a newsletter a quarter century<br />

ago that evolved into <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> magazine.)<br />

According to board chair Mark Nickerson, an MRC founder,<br />

the organization sold its building in Amherst, Mass., closed its<br />

office in nearby Springfield, transferred oversight of Moving<br />

Forward, its widely regarded batterers’ intervention program, to<br />

a large area social service agency (which retained all interested<br />

program staff), and replaced remaining paid positions with a cadre<br />

of dedicated volunteers.<br />

“Our foresight and success in transferring [Moving Forward],<br />

and selling the building, left us with funds that will remain a nest<br />

egg for future MRC activities,” Nickerson said, adding that the<br />

organization will continue with other aspects of its work. “Our<br />

[four weekly] support groups…continue to provide a valuable<br />

resource to many men in the community.”<br />

The organization relocated to new administrative offices and,<br />

Nickerson said, has retained “numerous talented and experienced<br />

individuals available for speaking or consultation opportunities.”<br />

The MRC was scheduled to begin a visioning process in early<br />

2010.<br />

To learn more, visit www.mrcforchange.org.<br />

Winter 2010 5

Men @ Work<br />

significant effect of soy protein or<br />

soy isoflavone intake on circulating<br />

levels of testosterone, sex hormonebinding<br />

globulin or free testosterone<br />

in men. Led by Jill M. Hamilton-<br />

Reeves, Ph.D., R.D., of St. Catherine’s<br />

University in St. Paul, Minnesota,<br />

researchers assessed the effects<br />

of soy protein and soy isoflavones on<br />

measurements of male reproductive<br />

hormones.<br />

“As a high-quality source of<br />

protein relatively low in saturated<br />

fat, soy can be an important part of a<br />

heart-healthy diet and may contribute<br />

to a decreased risk of coronary heart<br />

disease,” according to reproductive<br />

endocrinologist William R. Phipps,<br />

MD, of the University of Rochester<br />

Medical Center, a co-author of the<br />

analysis. He noted that some men<br />

have been reluctant to consume soy<br />

foods due to concerns about estrogen-like<br />

effects of soy isoflavones,<br />

often referred to as phytoestrogens.<br />

But according to Phipps, “It is important<br />

for the public to understand<br />

that there is no clinical evidence to<br />

support these ideas. After conducting<br />

a comprehensive review of the existing<br />

literature, we found no indication<br />

that soy significantly alters male sex<br />

hormone levels.”<br />

To request a copy of the report,<br />

write Diana Steeble at Diana.Steeble@Publicis-PR.com.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong>s Against<br />

Violence<br />

<strong>Voice</strong>s Against Violence is a zine<br />

publishing work from people of<br />

color, indigenous folks, trans people,<br />

and queer survivors of domestic<br />

violence, sexual violence and sexual<br />

assault. Topics include: healing from<br />

trauma, enabling healing, life after<br />

trauma, self-help guides/resources,<br />

self-healing, dancing as means to<br />

healing, healing through narration,<br />

forgiveness (do we need it?), and<br />

collective trauma.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong>s Against Violence is a<br />

community teaching tool, a jumping<br />

off point for dialogue, creative outlet,<br />

and conversations zine editors say<br />

‘need to happen.” A part of Café<br />

Revolución (www.myspace.com/<br />

caferevolucion), <strong>Voice</strong>s Against<br />

Violence accepts submissions in<br />

English, Spanish, Tex-Mex, Spanglish<br />

or any combination via email, sent to<br />

noemi.mtz@gmail.com. (Translations<br />

are appreciated but aren’t<br />

necessary.)<br />

THANK YOU<br />

Boysen Hodgson<br />

H20 Marketing, website support.<br />

Tony Rominske<br />

Peace Development Fund,<br />

technical assistance.<br />

Visit our new website for the<br />

latest news and updates<br />

voicemalemagazine.org<br />

6 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

NO COMMENT<br />

Boyzilian Waxing: “Manscaping” for Men<br />

With a name like ours, <strong>Voice</strong><br />

<strong>Male</strong> receives a range of press<br />

releases, announcements and<br />

news about men and masculinity.<br />

In the interest of “transparency,”<br />

we wanted to share an<br />

edited version of a recent press<br />

release we received. ”<br />

The fastest-growing segment<br />

of the spa industry is the<br />

male client and waxing is at the<br />

top of the services men seek.<br />

<strong>Male</strong> body waxing is increasingly<br />

popular as awareness of<br />

the types of waxing services<br />

available for men grows. The<br />

“cavemen look” is out, and men<br />

are looking for more ways to improve<br />

their look and boost their<br />

confi dence.<br />

Back in the late 80’s men<br />

were experimenting with eyebrow<br />

waxing, a far better approach<br />

than tweezing one hair at<br />

a time. Then in the 90’s athletes<br />

and models expanded into body<br />

waxing, getting hair removed<br />

from their legs, chest, back,<br />

arms and fi ngers; anywhere their<br />

skin was exposed in a swimsuit.<br />

Realizing the benefi ts of waxing,<br />

the trends have evolved<br />

into a “baring it all” service, the<br />

Boyzilian.<br />

Boyzilian waxing “is the<br />

male version of the Brazilian<br />

Bikini Waxing service, but provided<br />

for men that want to feel<br />

clean and confi dent all the time,”<br />

says Susanna DiSotto, director<br />

of Satin Smooth, a manufacturer<br />

of professional wax products.<br />

What follows are tips for the<br />

novice client:<br />

WHAT IF I BECOME AROUSED?<br />

It’s not uncommon for guys<br />

to become somewhat aroused<br />

at the beginning of a service.<br />

However, it is short lived as it<br />

becomes clear with the fi rst hair<br />

removal that this is a procedure,<br />

rather than an encounter. While<br />

the benefi ts will outweigh the<br />

mild discomfort, the fi rst hairs to<br />

come out are usually enough to<br />

calm down anything that might<br />

have come up in the beginning.<br />

Shave it like Beckham?<br />

WHAT BENEFITS WILL<br />

I RECEIVE?<br />

Increased sensitivity, reduced<br />

body odors, and more<br />

attention! Men also fi nd that<br />

their partners enjoy the cleaner,<br />

fresher look and the feel of a<br />

little “Manscaping.” Plus, there<br />

is a basic color effect, dark recedes<br />

and light brings forward.<br />

Things simply look bigger when<br />

they are well groomed!<br />

DO I HAVE TO HAVE EVERYTHING<br />

TAKEN OFF?<br />

While some guys like a totally<br />

clean look, many men simply<br />

like to have a cleanup and<br />

shaping. More often than not,<br />

guys just want to clean the hair<br />

off the shaft of the penis and remove<br />

hair from the scrotum, the<br />

anus and in between. Some trimming<br />

of the hair above the pubic<br />

bone and they’re ready for the<br />

world. It’s all negotiable, so a<br />

clean consultation should eliminate<br />

any surprises.<br />

ANYTHING ELSE I SHOULD<br />

KNOW?<br />

Don’t consume caffeine immediately<br />

before your appointment,<br />

as it can increase sensitivity.<br />

Wear loose clothing and<br />

cotton boxer shorts. No tight<br />

jeans or hot showers the day of<br />

the appointment. Also plan to<br />

wait a day before you share the<br />

new “do” with your mate.<br />

Editor’s Note: Have an item for<br />

the “No Comment” section?<br />

Send to editor@voicemalemagazine.org.

Dear <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> Reader,<br />

As our country’s 30,000 Afghanistan-bound soldiers’ pounding hearts amplify the drumbeat of war, I am<br />

moved to ask for your help. After President Obama’s speech in December announcing the troop increase,<br />

I found myself thinking about all the stories in <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> that articulate a new definition of manhood.<br />

Of course a magazine can’t stop a war. But it can help reframe our ideas about peace and about men transforming ourselves from war<br />

makers to peacemakers. And it can contribute to redefining masculinity for our sons, brothers, nephews, cousins—and for the boys in<br />

generations to come.<br />

Because I so strongly believe in the message of possibility—of a new vision of manhood—that <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> represents, I feel a special<br />

urgency in asking for your support. In the nearly 15 years since I first started editing the magazine, we’ve published more than 1000 articles,<br />

all with an eye toward men rethinking masculinity. The good news is, even in these challenging times, more men are changing.<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> at Historic Conference of College <strong>Male</strong>s<br />

Consider: In November, <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> was at St. John’s University in Minnesota at the first national conference of men working for gender<br />

equality and challenging violence against women on college and university campuses. Interviewed for an article in Ms. <strong>Magazine</strong> online, I<br />

suggested the historic conference “represents a sea change” in feminist/profeminist collaboration. “One of the old-timers among male feminist<br />

allies, Rob Okun, editor of <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> magazine said, ‘There’s a new generation of men coming to these issues.’” And it was thrilling<br />

meeting with them—new gender justice activists, fired up and ready to go. It was heartening to see these students taking <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> out<br />

of their conference packets to read during the two-and-a-half-day gathering. (Indeed, this past year <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> was similarly featured at<br />

conferences in New York and Washington, and was widely distributed to hundreds of delegates from 80 countries at an international men’s<br />

gender equality symposium in Rio de Janeiro.) In 2009 thousands received the magazine, including many women and men representing<br />

key agencies in the U.S and abroad inspired by our message advocating for a healthy expression of masculinity—improving men’s health,<br />

advocating for gay rights (including marriage rights), being engaged fathers and mentors, and preventing violence against women.<br />

At the plenary session in Minnesota at which I spoke it was clear something historic was happening. While sexual violence and domestic<br />

abuse remain an international calamity, from the streets of our cities to remote parts of the Congo, young people deeply understand the<br />

issues <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> articulates are part of—not distinct from—the greater movement for social justice. Our “voice” is advancing our cause—<br />

and women, children, and men are the better for it. Still, we need your help.<br />

New Members of National Advisory Board<br />

I’m delighted to share the news that there are three new members of the <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> national advisory board:<br />

• Activist-playwright Eve Ensler (author of The Vagina Monologues, and founder of V-Day)<br />

• Profeminist activist Charles Knight (who maintains the blog Other & Beyond Real Men)<br />

• Writer-professor Shira Tarrant (author of Men & Feminism and editor of Men Speak Out)<br />

Shira and Charles have been involved in profeminist men’s work for a long time and are committed leaders. Both spoke at the conference<br />

in Minnesota. In launching V-Men—the “men’s auxiliary” to V-Day— Eve articulated her passion for women and men collaborating.<br />

In 2010, I anticipate strengthening <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>’s ties with V-Day and V-Men and expanding our distribution so more and more women and<br />

men—and especially younger men and women—have opportunities to read the magazine online and in their communities.<br />

There really isn’t another publication like <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong>. With so many social issues rooted in damaging expressions of old-style masculinity,<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> is needed more than ever. Please support us by taking out or renewing your subscription. And, please consider making a<br />

contribution so we can grow in 2010 and beyond.<br />

With appreciation,<br />

Rob Okun<br />

Editor<br />

P.S. Please use the enclosed response form and envelope or go to www.voicemalemagazine.org.<br />

Winter 2010 7

Outlines<br />

Anti-Gay Hate Crimes and the Problem of Manhood<br />

The <strong>Male</strong> Straitjacket<br />

By Brendan Tapley<br />

In late 2008, a different “surge”<br />

emerged in the headlines. The<br />

FBI released its statistics for<br />

hate crimes in a good news bad<br />

news report. Good news: overall,<br />

hate crimes declined from the<br />

previous year; bad news: there<br />

was a 6 percent surge in incidents<br />

against homosexuals—the<br />

only category that increased—the<br />

majority of which targeted gay<br />

men (59.2 percent versus 12.6<br />

percent for gay women). What<br />

was unclear was the reason; the<br />

FBI was quick to say its report did<br />

not assign causes for fluctuations.<br />

Now, in the wake of the Matthew<br />

Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention<br />

Act recently becoming law, it<br />

seems worth proposing one.<br />

Most men will admit that<br />

publicly demonstrating affection<br />

toward another man—even<br />

platonic affection—can incite<br />

from fellow men “the look.” Often<br />

enough, that look precedes threats<br />

or much worse, as in the cases<br />

of Jose Sucuzhanay (murdered<br />

for walking arm-in-arm with his<br />

biological brother), Lawrence<br />

King (shot in the head for giving<br />

an eighth-grade classmate a Valentine<br />

card), or any of 2008’s 1,460 hate crime victims.<br />

So far, I’ve been fortunate not to confront anything “statistical,”<br />

but the looks and slurs that I’ve received make me a guy who alternates<br />

between showing affection for my male friends and someone<br />

who worries about the implications. Whenever I’ve experienced this<br />

disapproval I’ve resented those who generate it, which is why it was<br />

interesting when I became the “looker.”<br />

I was walking in Rome when for the third time that day I noticed<br />

two men acting affectionately toward one another. I only realized my<br />

eyes had narrowed because, when I passed the third pair, arm-in-arm,<br />

they returned my gaze with irritation. Taken aback by the expression<br />

I’d made and the one it elicited, I became more astonished by the<br />

cause I knew I could assign to it. My problem wasn’t prejudice. It<br />

was envy.<br />

From an early age, men in this country are trained to go without<br />

love or loving gestures from fellow men. When that principle of<br />

manhood becomes clear, our longing for such love does a paradoxical<br />

8 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

thing: it both intensifies and goes<br />

underground. Men cannot help<br />

but feel an increased desire to<br />

fill this void; at the same time,<br />

we rarely act on it because, by<br />

seeming gay, such a desire still<br />

contradicts our modern definition<br />

of masculinity.<br />

Enter the “danger” of gay<br />

men. These men pursue and act<br />

on male intimacy as though it<br />

should be a given, even a right.<br />

Should a man find himself in<br />

the presence of loving gestures<br />

from or between such men, he is<br />

likely to feel, as I did, a psychic<br />

split: regarding such overtures as<br />

tempting and incriminating. This<br />

internal clash between a man’s<br />

long-held desire and his selfdenial<br />

can turn a passing disapproval<br />

into problematic envy<br />

and that envy into resentment,<br />

even rage.<br />

I didn’t want to hurt the Italians;<br />

on the contrary, they had<br />

what I wanted: an open fraternity<br />

that was so unassailably<br />

appropriate its expression was<br />

blasé. But no sooner had I felt<br />

that longing than it mutated into<br />

an instinctive hostility. However<br />

absurd this reaction was, I also saw its logic.<br />

As is often true of men, anger conceals our real feelings; in this<br />

case, my sorrow. The scorn I’d felt for the Italians allowed me to<br />

ignore the disappointing ways I daily surrendered to the masculine<br />

tragedy of forgoing true male connection. Such a judgment also<br />

excused me from being a braver man who would fight against this<br />

fate by risking my own gestures. Indeed, the knee-jerk allegiance I<br />

had to what a “real man” was prevented me from actually being one,<br />

clarifying for me the real root of homophobia.<br />

The aversion to male love—whether it remains internal or<br />

becomes criminal—is not about prejudice. Prejudice is a “palatable”<br />

alibi that denies a darker truth. Homophobia is a common reaction<br />

to love between men because admitting such love is possible forces<br />

men to reevaluate the male “contract.” And that presents men with<br />

their own good news bad news situation.<br />

Witnessing real male connection—becoming aware of our longing<br />

for it—threatens masculinity, not just because it brings up in men our

uneasiness in feeling gay, but more because it exposes masculinity<br />

for the raw deal it is: an existential cheat that has defrauded men of a<br />

full 50 percent of human connection. Unlike women, who create rich<br />

ties within the sisterhood, this forfeiture has lodged<br />

an unspoken complaint within our psyches, a primal<br />

disenfranchisement that prevents our wholeness.<br />

But while an unapologetic conviction by men that<br />

male love is part of masculinity would free us from<br />

an inherent and stunting bondage (good), it would<br />

also sacrifice male privilege (a loss that, at first<br />

glance, seems bad).<br />

For instance, would demanding love from our<br />

fathers be worthwhile if it meant our accountability<br />

as fathers became more rigorous? If love<br />

between men was more common than exceptional,<br />

would we have to meet a standard of brotherhood that exceeded the<br />

frat house and was honored beyond the battlefield? If this subconscious<br />

grievance in maleness disappeared, would we have to get on<br />

with the business of being fully present, intimate, and responsible to<br />

the women in our midst? If male love was no longer taboo, would<br />

we have no one to oppress to feel better about ourselves?<br />

Indeed the reinvention of masculinity ends with what some might<br />

see as a Pyrrhic victory— the extinction of masculinity’s excuses, its<br />

low expectations. Because renegotiating the male contract will strip<br />

from us the straitjacket whose limitations we men may uncomfortably<br />

but willingly wear.<br />

This is the real reason men fight demonstrations of male love.<br />

Or in the case of gay hate crimes, why we increasingly attack the<br />

If male love<br />

was no longer<br />

taboo, would we<br />

have no one to<br />

oppress to feel<br />

better about<br />

ourselves?<br />

messengers of what is a new and coming masculinity. Those who get<br />

out of masculinity’s raw deal by no longer accepting privation enrage<br />

those who abide by it still. Our closeted envy of gay men, rather than<br />

letting it transform us or masculinity’s rules, instead<br />

makes pariahs out of the pioneers. We turn their<br />

example into a grave offense for the worst reason:<br />

to preserve a self-destructive privilege.<br />

Is it any coincidence that in the bluest states<br />

in America—where homosexuality is presumably<br />

more explicit—the FBI counted most of the hate<br />

crimes? Massachusetts (80) and California (263)<br />

versus Alabama (1) and Louisiana (2). In the case of<br />

hate crimes against gays, perhaps it is not a matter<br />

of irrational hate at all, but of rational love that men<br />

just don’t want in evidence. Because even more<br />

explosive than a man confronting a perception of homosexuality<br />

and exercising his prejudice is the man who admits his crimes have<br />

always been against himself, and he has become his own jailer.<br />

Brendan Tapley is currently writing a memoir<br />

on masculinity. His work has appeared in<br />

the New York Times and Chicago Tribune,<br />

among others. He lives in New Hampshire.<br />

A version of this column appeared in the Bay<br />

Area Reporter, www.ebar.com.<br />

Winter 2010 9

Stepping Off the Pedestal of <strong>Male</strong> Privilege<br />

No More Mr. Good Guy?<br />

By Tal Peretz<br />

Ilike being “the good guy.” I<br />

really enjoy the appreciation and<br />

approval I get from women when<br />

I tell them that my chosen life’ s<br />

work involves ending sexism. I love<br />

the sense of connection I feel when<br />

they see me as an ally, a confidant,<br />

a guy who “gets it,” and I get to feel<br />

like we share a very big secret: that<br />

there are problems with the way our<br />

society’s gender rules are set. When I<br />

volunteer at a local women’s shelter,<br />

or march in a protest for women’s<br />

rights, I like to know that my presence<br />

is appreciated. Lately, though,<br />

I’ve been troubled by this feeling,<br />

especially because I’ve noticed that<br />

I sometimes get more appreciation<br />

than the other people there, and the<br />

only explanation I can come up with<br />

is that I get unearned kudos because<br />

I’m a man.<br />

I’ve been talking with a lot<br />

of men who do anti-sexist work,<br />

sometimes in formal interviews<br />

for academic research, sometimes<br />

among friends. For me, and many<br />

of these men, the reason we are<br />

against sexism is, at least in part,<br />

because of the harm we’ve seen<br />

sexist oppression do to women. The<br />

flip side of this is the unfair privilege<br />

granted to men just for being<br />

men. I worry that this unearned<br />

male privilege is still present when<br />

men are in anti-sexist spaces, doing<br />

anti-sexist work. This can create<br />

situations where, in the very spaces<br />

devised to further the concerns of<br />

women, men and their concerns take<br />

precedence. To be fully honest and<br />

complete in our work against sexism and<br />

unfair male privilege, we have to be aware<br />

of it within our movement as well, not just<br />

in the larger society.<br />

The Pedestal Effect<br />

To maintain awareness of this unearned<br />

male privilege and excess appreciation of<br />

men doing anti-sexist work, it helps to have a<br />

name and some idea of how it happens. I’ve<br />

10 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

taken to calling it “the pedestal effect.” As<br />

one interviewee said, it’s “things like praise<br />

for showing up—I didn’t necessarily do<br />

anything, I think it’s just…people are just so<br />

pleased to see a man who actually takes an<br />

interest, and I can see how that’s comforting<br />

or refreshing. But a lot of times it’s just the<br />

fact that I’ll put in the hours, and there’s<br />

other people who do as much as I do. . . it<br />

just seems like I get more than my share for<br />

doing my part.”<br />

Sometimes the pedestal effect<br />

is used to intentionally ensure that<br />

men know they are welcome and<br />

wanted in spaces where they are the<br />

minority, and so I don’t want to sound<br />

ungrateful. Like I said, I like knowing<br />

my presence is appreciated as much<br />

as the next person. I just want to<br />

make sure that the women doing the<br />

same work as me are getting the same<br />

appreciation.<br />

Men working against sexism are,<br />

sadly, still rare. A friend who has<br />

volunteered at a domestic violence<br />

and sexual assault shelter for a<br />

number of years put it succinctly:<br />

“Most of these organizations don’t<br />

see many men come through, or<br />

even bother caring.” Sometimes just<br />

this rarity brings special attention,<br />

leading to premature self-congratulation,<br />

to paraphrase Michael Kimmel.<br />

Kimmel also encourages us, correctly<br />

in my opinion, to recognize and<br />

appreciate that men do take risks and<br />

make sacrifices in working toward<br />

gender justice. But this means that<br />

those men who show up seem exceedingly<br />

selfless, perhaps even inherently<br />

“special.” I’ve experienced<br />

this when someone introduces me<br />

and says “He gets it,” or “He’s one<br />

of the good guys.” Whereas women<br />

working against sexism are seen as<br />

working in their own self-interest,<br />

any effort men make for women’s<br />

rights is seen as selfless, and thus<br />

more virtuous than the same effort by<br />

a woman (even if the person judging<br />

is also a woman). This is one reason<br />

for the pedestal effect.<br />

A second reason is simply that pervasive<br />

male supremacy in the rest of society benefits<br />

men so much that it carries over. Men come<br />

to this work from a society that has trained<br />

them from birth to believe in their own<br />

superiority, sometimes subtly and sometimes<br />

overtly. Although most men never recognize<br />

it as privilege, we are accustomed to being<br />

listened to, to people automatically assuming<br />

we are capable and competent, to being in

control of social situations, etc. The effects<br />

of this training don’t dissipate automatically,<br />

and there are very few opportunities for men<br />

to make the sustained, in-depth effort necessary<br />

for effective consciousness-raising (and<br />

of course, male socialization discourages<br />

exactly this sort of talking about emotions,<br />

deep issues, and personal pain). So, what can<br />

be done about it?<br />

Stepping Off the Pedestal<br />

A few years ago, when we both volunteered<br />

at the same shelter, a friend—let’s call<br />

him Mike—and I were talking. I mentioned<br />

that I always felt a little awkward and uncomfortable<br />

when the volunteer trainer thanked me<br />

for coming—I noticed that she didn’t thank<br />

anyone else nearly as much. Mike not only<br />

confirmed my opinion, he told me that she put<br />

him on the pedestal as well. Having been there<br />

longer than me, Mike had developed a strategy<br />

for dealing with inflated praise by saying: “If<br />

you need to [thank me], let my mother know.<br />

I’m sure she’d appreciate it.” I thought this<br />

was clever, because it redirects the focus of<br />

appreciation and the conversation.<br />

Since then, I’ve noticed other strategies<br />

some men use to reduce the effects of unfair<br />

privilege and unequal praise. Some, like<br />

Mike, pass along the appreciation to women<br />

they see doing the same work as them but<br />

getting less praise—their mothers, mentors,<br />

or other women in the room working alongside<br />

them. Others make an explicit point of<br />

frequently referencing and recognizing the<br />

contributions women have made to the work<br />

they do, and some of the particular women<br />

whose footsteps they are following. Perhaps<br />

the most important thing is just being aware<br />

of male privilege, and checking to make<br />

sure it isn’t contributing to the creation of a<br />

pedestal under you.<br />

Checking to make sure you aren’t being<br />

unfairly privileged can be awkward. It may<br />

even mean intentionally stepping back from<br />

rewarding positions that bring recognition<br />

if the position came to you due to male<br />

privilege. I was recently asked to give a talk<br />

for Women’s Week at a distant university.<br />

The organizers offered to cover my travel<br />

expenses, something not out of the ordinary<br />

in these situations. I accepted.<br />

As the date approached I got more and<br />

more uncomfortable, thinking about the<br />

fact that I was invited out there to speak<br />

because I am a man. What if some woman<br />

hadn’t been invited, so they could afford<br />

to fly me out there? Or, worse yet, what if<br />

women were invited but had to cover their<br />

own expenses? It might not be intentional,<br />

but the scarcity of male voices speaking on<br />

the topic might make my presence seem more<br />

valuable, thus garnering me special treatment<br />

that I hadn’t earned.<br />

I spent the better part of an hour<br />

composing a very polite and carefully worded<br />

e-mail, asking whether that was the case and<br />

informing them that if the budget was tight,<br />

I’d rather the money be spent on women<br />

presenters. I made clear that I greatly appreciated<br />

their offer, and would gratefully accept<br />

any funds they could make available, as long<br />

as I could be assured that I wasn’t getting<br />

special treatment because of my gender. They<br />

wrote back and let me know that that wasn’t<br />

the case, and that they would still very much<br />

like to have me. I felt a lot better about going,<br />

knowing that my presence was not taking<br />

away from the women who are my allies.<br />

Supporting and building alliances<br />

between and with marginalized groups is<br />

one of the most important things men can<br />

do. Simultaneously, though, we need to be<br />

holding each other accountable. We need to<br />

create spaces and find ways of supporting,<br />

coaching, guiding, and encouraging each<br />

other in the tricky and emotionally demanding<br />

task of working against our own privilege (as<br />

Mike did for me). We need to make sure we<br />

are being good people, not just “good guys.”<br />

A graduate student<br />

at the University of<br />

Southern California,<br />

Tal Peretz has been<br />

involved in men’s<br />

groups working to<br />

end men’s violence<br />

against women for<br />

seven years. After<br />

volunteering at a<br />

charter high school for underprivileged<br />

youth, working at an HIV/AIDS resource<br />

center, and doing counseling and advocacy<br />

at a domestic violence/sexual assault shelter,<br />

he is focusing his energy on enhancing the<br />

efforts of men working to end sexism.<br />

Winter 2010 11

Fathers and Sons<br />

Recovering from the War at Home<br />

Broken Father, Loyal Son<br />

By John Sheldon<br />

What is loyalty, specifically the loyalty of a boy to his father? That’s the<br />

question John Sheldon has been pondering for much of his adult life. The<br />

singer-songwriter and guitar virtuoso, who toured with Van Morrison before<br />

he was 20 and whose songs James Taylor has recorded, offers this meditation<br />

on the complicated relationship he had with his late father and what filial<br />

loyalty says about manhood.<br />

In the United States of America, a young man is expected to be loyal to<br />

his country. He is expected to defend the flag and all that it stands for.<br />

He is expected to honor all those who sacrificed for that very same flag,<br />

and to make sacrifices himself, up to and including the ultimate one—dying<br />

in war.<br />

But let’s go back. Let’s go back to look at the young man before he is old<br />

enough to accept these responsibilities. Think of him as a boy of around 11,<br />

an age at which the United States (or any country for that matter) is still an<br />

abstraction. The boy doesn’t live in a country yet. He “lives” in his school,<br />

his neighborhood, and most of all, in his family.<br />

My father was a craftsman. He made furniture. At 11 I didn’t know if<br />

his work was any good.<br />

I only knew that other men visiting our house would often admire a piece<br />

he’d made, sometimes telling me, “Your father is a true craftsman.”<br />

It came as a shock, then, one night, to hear loud crashing coming from the<br />

living room and to find my father standing over one of his masterworks—the<br />

scattered remains of a coffee table he had just destroyed. He was muttering<br />

angrily. I couldn’t understand anything he was saying. When my mother<br />

appeared, she stood in the doorway, arms folded. She didn’t enter the room or<br />

even speak. The coffee table, one of a pair Dad had made, lay in ruins on the<br />

rug. To my 11year-old self, the more he ranted, the larger its splintered legs<br />

and broken top became—no longer a pile of wood my dad had painstakingly<br />

shaped—but a dead body. My mother retreated from the doorway.<br />

Broken. Something broken. What was it? The coffee table, yes, but<br />

something else. My family, maybe? I took the cue from my mother’s silence,<br />

her folded arms; her stoicism. Something was broken, all right—it was my<br />

father.<br />

Are you listening to what I’m trying to tell you? From the first time my<br />

dad bounced me, sang to me, held me down and tickled me until I thought<br />

12 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

I’d die laughing and grateful, from the first time I felt, in his physicality, that<br />

he could be rough and tender at the same time, there was no one in the world<br />

that I could have ever loved more.<br />

I’ve heard so much talk about a child’s relationship with his mother, the<br />

suckling warmth and intimacy of it all. Not me. I was shaped by my father’s<br />

knobby and powerful hands. When he held me or bounced me or tickled me<br />

those hands said in language plain as day, I am strong. I could kill you easily,<br />

but I won’t. And I could feel he wouldn’t. I could feel it in his hands. How<br />

could anything or anyone have inspired the loyalty in me that my dad did?<br />

Yet at 11 years old I learn that my father is broken. Why? Does it matter<br />

why? His mother abused him. He cleaned up blood—and bodies—in World<br />

War II. He drinks too much. Whatever it is, it’s not as important as what to do<br />

now. I don’t have to clean up the living room. I know my mother will do that.<br />

Everything will be cleaned back to normal—everything but my knowledge<br />

that I have a busted father. I cannot bear carrying this knowledge.<br />

So here’s where the loyalty kicks in, the loyalty that will determine the<br />

direction of my life from that moment. Because, somewhere in the barely<br />

visible outline of impending manhood, I know my job—to fix him.<br />

But how? How could a boy possibly know how to reassemble a human<br />

being? I didn’t even have the skill to fix the coffee table. So, in some dim<br />

recess of awareness, I hit on an answer. I will become broken myself! Can<br />

you see—and marvel at—the elegant logic of it all? If I am the broken one,<br />

my father will become whole again. I know this to be true. I will take this<br />

on, this brokenness, embody it, bear it away from him, suck the poison out<br />

of him and, at the same time, out of my family. It is my responsibility. Being<br />

the son, I am the protector now.<br />

How do I become broken? The answer comes in a flash: by doing what<br />

Dad did. Smash things. I’d done this on a small scale before, smashing a<br />

couple of model airplanes when I messed up, but I’d never done anything<br />

on this scale before.<br />

Over the next several years I started to smash my life. I became a fuckup<br />

at school, got kicked out, went to another school where they couldn’t kick<br />

me out, then started cutting my arm with razors and broken glass, smashed<br />

some furniture myself, and was placed on a mental ward as a teenager. There<br />

I was, away from my friends, away from my room with the books and model<br />

planes, my backyard, and yes, my dad.<br />

I became the broken one.<br />

Of course that was the opposite of what my dad wanted for me and I<br />

fixed nothing. I only set myself on a trajectory from which I am still trying<br />

to return.<br />

Working with old tools in a dim workshop<br />

I try to repair what has been damaged<br />

I did not want the job<br />

But now that I have it, I will snap at you if you interrupt me.<br />

I will reject any offer to help<br />

There is no one as qualified to do this work<br />

Of gluing my broken father back together<br />

To make you whole again<br />

What wouldn’t I do<br />

To mend your soul again<br />

What wouldn’t I go through<br />

Truth be told<br />

No glue will hold a thing so vast

Nothing that will last<br />

The time is flying<br />

Why can’t I stop trying<br />

To make you whole again<br />

Oh, my father<br />

The distance between us now<br />

So much wider<br />

I just don’t know how<br />

To cross the space<br />

Return to the place<br />

Where we can both feel strong<br />

It’s been too long<br />

Midnight has come<br />

I’ve just now begun<br />

To try to make us whole again<br />

I was 16 when I got out of the hospital. My new friends were all people<br />

who had been or were still in the hospital. My father and I tiptoed around<br />

each other, as if both of us knew the truth but couldn’t acknowledge it.<br />

I put my life back together around music, and my ability to play the<br />

electric guitar. I got work that way, and some sense of self-esteem. But I<br />

could never return to the “regular” society of school and preparation for a<br />

prescribed life. It felt as if it was all beyond me. I knew too much. I knew<br />

the keepers of the keys were as insane as the inmates.<br />

I took the fall for Dad because I loved him.<br />

Tell me this loyalty for the father is not stronger than all the flags, all<br />

the tomes about freedom and sacrifice. Tell me our leaders don’t somehow,<br />

through propaganda and rhetoric, use this loyalty to our fathers to get us to<br />

sacrifice ourselves again and again, in the wars they have started? Somebody,<br />

somewhere prove to me that this is not so!<br />

In this society few know what it means to be a man. We have few rituals<br />

where a man can pass on a healthy manhood to his son. Sons are on their<br />

own trying to interpret how to express love, or anger, grief or joy. What do<br />

boys and men do? Follow in our fathers’ unsure footsteps? Totally reject<br />

everything they stand for? What about ending it all—the ultimate sacrifice?<br />

I know many times I thought if I killed myself then the poison I had swallowed<br />

would die with me. How wrong I was! I had friends who did it. What<br />

wells of pain and misery they left behind.<br />

Most men are typecast as the fixers of things. Maybe that’s not wrong.<br />

How many of us have opened the hood of the car to try and find the<br />

problem? Why won’t we open the hood of our stalled lives—the fatherson<br />

relationship? Can someone please tell me what is more important? Instead<br />

of wasting our time trying to figure out how to fix the car—or the country,<br />

or someone else’s country—why don’t we start with the broken love of a<br />

father and son?<br />

Is there any way we can look our fathers in the eye and say, “I love you,<br />

Pop. I’ll do anything for you, but I will not break myself for you. I will not<br />

die for you!”<br />

I am one of the lucky ones. I didn’t die. I kept on playing the guitar and<br />

slowly, over time, carved out a ledge to stand on, maybe not in the mainstream,<br />

but on the edge somewhere.<br />

I survived the war at home with both arms, both legs, and with my brain<br />

largely intact. I had plenty of guilt about surviving, and the guilt caused me<br />

to linger in the land of the broken. It was easier to live in the cracked image<br />

of my father than to emerge into my own strength—probably the remnants<br />

of my loyalty to him. I could not be stronger than him for fear that it would<br />

break him more. It was only when he was ailing, dying of cancer, that I began<br />

to discover the reserves of strength and resiliency I<br />

had within me all along, qualities I felt as a child ,in<br />

his knobby, powerful hands. I believe that, in the first<br />

few years of my life, my father’s hands had taught me<br />

something after all.<br />

John Sheldon is a guitarist, composer, and songwriter.<br />

He lives in Amherst Mass.<br />

Winter 2010 13

Men, the Mainstream Press, and Rape in the Congo<br />

Invisible Men<br />

By Jackson Katz<br />

Despite a generation of feminist<br />

activism which inspired changes in<br />

countless laws and social practices,<br />

in public life it is far from clear that women’s<br />

experiences and voices count as much as<br />

men’s. United States Supreme Court justice<br />

Ruth Bader Ginsburg recently provided an<br />

inside look at how this works in the highest<br />

provinces of power, when she questioned<br />

her own influence at justices’ conferences:<br />

“I will say something—and I don’t think<br />

I’m a confused speaker—and it isn’t until<br />

somebody else says it that everyone will<br />

focus on the point.”<br />

Ginsburg was too politically cautious—or<br />

polite—to note that the “somebody else” to<br />

whom she was referring was coded language<br />

for a man, whose opinion is deemed more<br />

valid by virtue of his sex. Men’s expertise<br />

and opinions are routinely valued more than<br />

women’s, here and around the world.<br />

How ironic and revealing, then, that what<br />

came to be known in mainstream accounts as<br />

“The Exchange” between Secretary of State<br />

Hillary Clinton and a young man at a public<br />

event in Kinshasa during Clinton’s visit to the<br />

Congo in the summer of 2009 overshadowed<br />

the substance of her trip, which shone the<br />

14 <strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong><br />

spotlight on the ongoing epidemic of sexual<br />

violence. (Secretary Clinton, you may recall,<br />

testily responded to the student’s question<br />

seeking “President Clinton’s” opinion about<br />

a political issue. It turned out the student had<br />

misspoken, and had meant to ask about President<br />

Obama. Secretary Clinton was evidently<br />

irritated that once again, her own opinions<br />

and experience were seemingly being overlooked<br />

in favor of the sexist presumption that<br />

a woman leader is merely the mouthpiece for<br />

a more powerful man.)<br />

Why was so much media coverage<br />

devoted to that during her trip to Africa<br />

when one of the secretary’s goals was to use<br />

the power of her voice to highlight African<br />

women’s lives? In particular, Clinton wanted<br />

to draw public attention to the ongoing<br />

tragedy of mass rapes of women, children<br />

and men in the Congo. She was the first U.S.<br />

secretary of state to travel to the war zone,<br />

and she announced a $17 million plan to<br />

fight sexual violence. Among other steps, the<br />

American government would train doctors,<br />

supply rape victims with cameras to document<br />

their injuries, and train Congolese law<br />

enforcement to crack down on rapists.<br />

Corporate and independent media did<br />

cover this part of the story, although with<br />

nothing like the gusto with which they<br />

recounted Ms. Clinton’s short-tempered<br />

response to the African student. Many<br />

American reporters in the ever-shrinking<br />

international press corps tried to convey the<br />

scope of the horrific suffering of women and<br />

children in the Congo, as well as communicate<br />

empathy with the emotional toll it all<br />

appeared to be taking on Ms. Clinton. “I<br />

was just overwhelmed by what I saw,” she<br />

said. “It is almost impossible to describe the<br />

level of suffering.” Several news accounts<br />

observed that Ms. Clinton seemed drained<br />

by the emotional experience.<br />

Unfortunately, however, the focus in<br />

news stories on the almost-unimaginable<br />

sexual violence in the Congo had an unintended<br />

effect. It pushed women’s lives to<br />

center stage, which is appropriate, necessary,<br />

and represents a big step forward. At<br />

the same time, it kept men out of the spotlight—at<br />

just the wrong time. <strong>Male</strong> leaders<br />

often get too much credit, and our opinions<br />

are unfairly more valued than women’s. But<br />

when it comes to being held responsible for<br />

the negative consequences of our behavior,

including the widespread incidence of rape<br />

around the world, men are typically rendered<br />

invisible in the journalistic conversation.<br />

Men’s role in rape is characteristically<br />

hidden in mainstream journalism through a<br />

variety of linguistic conventions. One of the<br />

more significant of these is when writers and<br />

speakers use the passive voice—consciously<br />

or not—to talk about incidents of sexual<br />

violence (e.g. “200,000 women have been<br />

raped since the conflict began”). In addition,<br />

men’s central responsibility for the rape<br />

pandemic escapes critical examination whenever<br />

writers and speakers use gender-neutral<br />

terminology to talk about perpetrators, who<br />

are overwhelmingly men. A New York Times<br />

article on August 12 last year reporting on<br />

Secretary Clinton’s trip provides a good case<br />

study of these phenomena.<br />

The article appeared beneath the fold<br />

on page A8, in the International section. It<br />

was headlined “Clinton Presents Plan to<br />

Fight Sexual Violence in Congo,” by Jeffery<br />

Gettleman. The passive voice began in the<br />

first paragraph: “...Secretary Clinton...met<br />

a Congolese woman who had been gangraped<br />

while she was eight months pregnant.”<br />

Passive sentence structures that hid male<br />

perpetration appeared in subsequent paragraphs:<br />

“...hundreds of thousands of women<br />

have been raped in the past decade.” And<br />

“...countless women, and recently many<br />

men, have been raped.” Then, “Hundreds of<br />

villagers have been massacred” and “The aid<br />

worker told Mrs. Clinton that an 8-year-old<br />

boy who had strayed out of the camp was<br />

raped the other day.”<br />

This brief catalogue of passive sentences<br />

is not an attempt to single out the New York<br />

Times reporter for criticism. He was merely a<br />

vehicle for the transmission of the dominant<br />

ideology, which routinely obfuscates men’s<br />

culpability for rape through both conscious<br />

and unconscious omissions. Victims themselves<br />

often use passive voice. Gettleman<br />

quoted one woman, Mrs. Mapendo, who<br />

said, “Our life is very bad. We get raped<br />

when we go out and look for food.” Another<br />

woman said, “Children are killed, women<br />

are raped and the world closes its eyes.”<br />

In addition to the passive language, the<br />

photo accompanying the story showed Secretary<br />

Clinton in an outdoor meeting with a<br />

throng of Congolese women. There was not a<br />

man’s face in sight. In fact, the only mention<br />

of the word “men” in the entire 1029-word<br />

article was in reference to men as victims of<br />

rape. If it had not been for that (welcome)<br />

acknowledgment of men’s vulnerability and<br />

victimization, a naïve reader might have<br />

inferred that there are no men in the Congo,<br />

only “women and children who are raped<br />

and killed.”<br />

The New York Times article was also<br />

suffused with gender-neutral language,<br />

particularly language that could have identified<br />

the gender of the individuals and groups<br />

responsible for sex crimes. For example:<br />

“Often the rapists are Congolese soldiers,”<br />

or “...Congo...has become a magnet for<br />

all the rogue groups in Africa.” Secretary<br />

Clinton was quoted as saying the world<br />

needed to regulate the mineral trade to make<br />

sure the profits do not end up “in the hands<br />

of those who fuel the violence.”<br />

Discussions about sex<br />

crimes, in the Congo<br />

and elsewhere, focus<br />

on what is happening to<br />

women, and not on who<br />

is doing it to them: men.<br />

But while the gender of the perpetrators is<br />

obscured, the gender of the victims is stated<br />

plainly. The following sentence provides<br />

a clear illustration of this: “...an intensely<br />

predatory conflict driven by a mix of ethnic,<br />

commercial, nationalist, and criminal interests,<br />

in which various armed groups often<br />

vent their rage against women.” This type of<br />

language usage is ubiquitous in contemporary<br />

journalism. When the perpetrators are<br />

men, their gender is not mentioned (“armed<br />

groups”). When the victims are women, their<br />

gender is in full view.<br />

The result is that discussions about sex<br />

crimes, in the Congo and elsewhere, focus<br />

on what is happening to women, and not<br />

on who is doing it to them. In practice, this<br />

has obvious repercussions for so-called<br />

prevention efforts, which as a result of their<br />

focus on women often amount to mere<br />

band-aid solutions. Of course rape victims<br />

and survivors need better medical and counseling<br />

services. But let’s not mistake those<br />

services for prevention—which can only be<br />

successful to the extent that men and boys<br />

are a part of them.<br />

The growing movement to engage men<br />

and boys in sexual and domestic violence<br />

prevention in the United States, sub-Saharan<br />

Africa, and around the globe—a movement<br />

<strong>Voice</strong> <strong>Male</strong> chronicles—faces an uphill<br />

climb in societies where cultural norms<br />

about masculinity both contribute directly<br />

to the violence and prevent women and men<br />

from speaking freely about men’s responsibilities<br />

to end it.<br />

This is not merely an academic debate<br />

about linguistic practices. Linguistic choices<br />

have practical consequences, especially in<br />

terms of what sorts of issues get discussed,<br />

and by whom, on main streets, in back rooms<br />

and in the shadowy corridors of power. As<br />

long as political leaders and policy makers—<br />

in national and international contexts—focus<br />

on rape primarily as a women’s issue, strategies<br />

for addressing it will tend to emphasize<br />

services for victims and survivors, rather<br />

than accountability for perpetrators, or more<br />

critical attention to how we socialize boys.<br />

Unfortunately, the failure of journalists<br />

and others to use active language to describe<br />

who is doing what to whom, as well as their<br />

hesitation to use gender-specific language to<br />

talk about men and boys as the perpetrators<br />

of sexual violence, make it next to impossible<br />