A Review of Criticality Accidents A Review of Criticality Accidents

A Review of Criticality Accidents A Review of Criticality Accidents A Review of Criticality Accidents A Review of Criticality Accidents

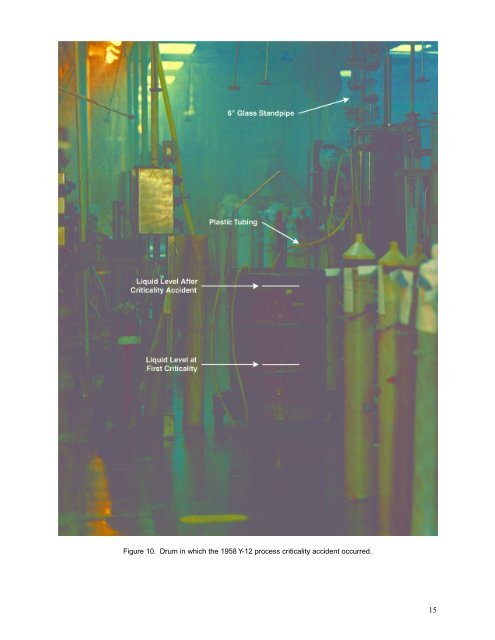

Figure 9. Simplified diagram of the C-1 wing vessels and interconnecting piping involved in the accident. valve V-3 was already open, and the flow pattern from the three vessels was such that any liquid in vessel FSTK 1-2 would flow into the drum first, the uranyl nitrate solution preceded the water. At approximately 14:05, the operator looked into the drum and noticed yellow-brown fumes rising from the liquid. He stepped away from the drum and within a few seconds saw a blue flash indicating that an excursion had occurred. Almost immediately thereafter, the criticality alarm sounded, and the building was evacuated. Further flow of water increased the uncompensated reactivity for about 11 minutes, then decreased it. The solution became subcritical after about 20 minutes. Later studies determined that a full 15 minutes elapsed between the time valve V-11 was opened and the system reached the critical point. It is unknown why the operator stationed near the drum (6 years of experience with uranium processing) did not notice the yellow colored uranyl nitrate pouring into the drum. At the time the system became critical, the solution volume is thought to have been ~56 l in a cylinder that was 234.5 mm high and 552 mm in diameter. The 235 U mass at the time was 2.1 kg, with 0.4 kg being added later, while water was further diluting the system. During the excursion a radiation detection instrument (boron lined ionization chamber, amplifier, and recorder) operating ~430 m from the accident location was driven off the scale by the radiation intensity. The trace from this detector also shows that about 15 seconds after the initial excursion it was again driven off scale. During the next 2.6 minutes, the trace oscillated an indeterminate number of times. It is possible that the oscillations were decreasing in amplitude, although it cannot be confirmed by examining the trace. This was followed for 18 minutes by a slowly decreasing ramp, about five times above background. The excursion history can be reconstructed only qualitatively. The most likely source of initiation was 14 FSTK 6-2 FSTK 6-1 FSTK 1-2 V-5 V-4 V-3 C-1 Wing 5" (127 mm) Storage Vessels 55 Gallon Drum V-11 V-2 6" Glass Standpipe pH Adjustment Station Gravity Flow of Uranyl Nitrate Solution From B-1 Wing V-1 neutrons from (α,n) with the oxygen in the water. Thus, it is possible that the system reactivity slightly exceeded prompt criticality before the first excursion. The reactivity insertion rate was estimated to be about 17 ¢/s at the time. The size of the first spike must have been determined by the reactivity attained when the chain reaction started. Although there is no way to be certain, a reasonable estimate is that the first spike contributed about 6 × 10 16 fissions of the total yield of 1.3 × 10 18 fissions. The second excursion, or spike (which also drove the recording pen off the scale), occurred in 15 seconds, a quite reasonable time for existing radiolytic gas bubbles to have left the system. The excursions for the next 2.6 minutes appear to have been no greater than about 1.7 times the average power. The trace suggests that most of the fissions occurred in the first 2.8 minutes, in which case the average power required to account for the observed yield is about 220 kW. After this, the system probably started to boil, causing a sharp decrease in density and reactivity and reducing the power to a low value for the final 18 minutes. Figure 10 is a photograph taken of the 55 gallon drum shortly after the accident. There was no damage or contamination. Eight people received significant radiation doses (461, 428, 413, 341, 298, 86.5, 86.5, and 28.8 rem). At least one person owes his life to the fact that prompt and orderly evacuation plans were followed. One person survived 14.5 years, one 17.5 years, the status of one is unknown, and five were alive 29 years after the accident. Shortly after the accident, a critical experiment was performed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) that simulated the accident conditions. This was done to provide information about probable radiation exposures received by the people involved in the accident. The plant was returned to operation within three days.

Figure 10. Drum in which the 1958 Y-12 process criticality accident occurred. 15

- Page 1 and 2: LA-13638 Approved for public releas

- Page 3 and 4: A Review of Criticality Accidents 2

- Page 5 and 6: PREFACE This document is the second

- Page 7 and 8: Tom Jones was invaluable in generat

- Page 9 and 10: C. OBSERVATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED

- Page 11 and 12: FIGURES 1. Chronology of process cr

- Page 13 and 14: 51. MSKS and assembly involved in t

- Page 15 and 16: A REVIEW OF CRITICALITY ACCIDENTS A

- Page 17 and 18: 3 Black Sea Baltic Sea Obninsk Norw

- Page 19 and 20: North Atlantic Ocean Irish Sea Wind

- Page 21 and 22: 1. Mayak Production Association, 15

- Page 23 and 24: time of the accident. However, the

- Page 25 and 26: determined by a radiation control p

- Page 27: consequences of this accident, the

- Page 31 and 32: The entire plutonium process area h

- Page 33 and 34: 7. Mayak Production Association, 5

- Page 35 and 36: During the next shift, radiation sa

- Page 37 and 38: 9. Siberian Chemical Combine, 14 Ju

- Page 39 and 40: The accident investigation determin

- Page 41 and 42: 10. Hanford Works, 7 April 1962 18,

- Page 43 and 44: heater and stirrer were turned off

- Page 45 and 46: vessel 64-A was added. The dissolut

- Page 47 and 48: additional reflection afforded by t

- Page 49 and 50: 15. Electrostal Machine Building Pl

- Page 51 and 52: 16. Mayak Production Association, 1

- Page 53 and 54: ased on a radiation survey, that th

- Page 55 and 56: 0.5 m 0.5 m 0.5 m 0.5 m 3.0 m 1.4 m

- Page 57 and 58: The investigation identified severa

- Page 59 and 60: 19. Idaho Chemical Processing Plant

- Page 61 and 62: 20. Siberian Chemical Combine, 13 D

- Page 63 and 64: To Glovebox 6 7 8 6 From Glovebox 6

- Page 65 and 66: on a 0.4 m square pitch grid. The b

- Page 67 and 68: competing reactivity effects proved

- Page 69 and 70: Figure 35. The precipitation vessel

- Page 71 and 72: B. PHYSICAL AND NEUTRONIC CHARACTER

- Page 73 and 74: Material Fissile Mass: Fissile mass

- Page 75 and 76: 235 U Spherical Critical Mass (kg)

- Page 77 and 78: Table 10. Accident Fission Energy R

Figure 10. Drum in which the 1958 Y-12 process criticality accident occurred.<br />

15