Army - Stimulating Simulation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

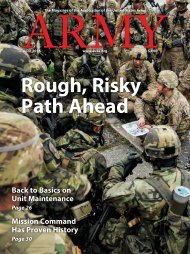

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

ARMY<br />

March 2016 www.ausa.org $3.00<br />

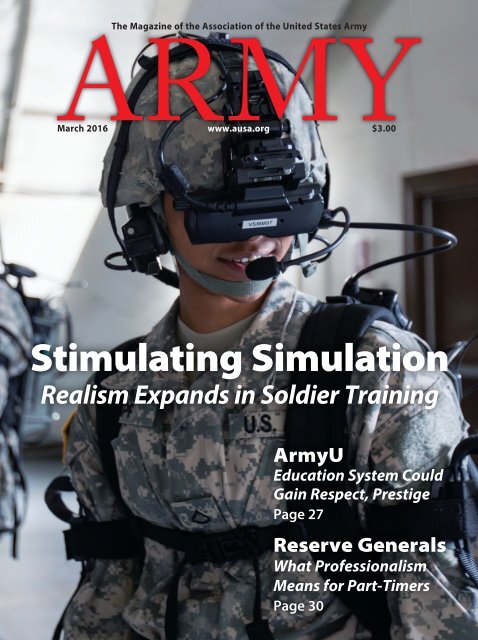

<strong>Stimulating</strong> <strong>Simulation</strong><br />

Realism Expands in Soldier Training<br />

<strong>Army</strong>U<br />

Education System Could<br />

Gain Respect, Prestige<br />

Page 27<br />

Reserve Generals<br />

What Professionalism<br />

Means for Part-Timers<br />

Page 30

THIS CONNECTED.<br />

ONLY CHINOOK.<br />

The CH-47F Chinook is the world standard in heavy-lift rotorcraft, delivering unmatched multi-mission<br />

capability. More powerful than ever and featuring advanced flight controls and a fully integrated digital<br />

cockpit, the CH-47F performs under the most challenging conditions: high altitude, adverse weather,<br />

night or day. So whether the mission is transport of troops and equipment, special ops, search and rescue,<br />

or delivering disaster relief, there’s only one that does it all. Only Chinook.

ARMY<br />

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

March 2016 www.ausa.org Vol. 66, No. 3<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

LETTERS....................................................3<br />

SEVEN QUESTIONS ..................................5<br />

WASHINGTON REPORT ...........................7<br />

NEWS CALL ..............................................9<br />

FRONT & CENTER<br />

The Risk of Another Unsuccessful War<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.<br />

Page 13<br />

Definition of ‘Decisive’<br />

Depends on Context<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.<br />

Page 14<br />

Refugees Display Courage<br />

To Move Forward<br />

By Emma Sky<br />

Page 16<br />

Draft a Bad Idea, With<br />

Or Without Women<br />

By Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano, USA Ret.<br />

Page 17<br />

Bond of Brothers: Infantrymen<br />

Stand Alone but Are Uniquely United<br />

By Col. Keith Nightingale, USA Ret.<br />

Page 19<br />

Millennials: Understanding This<br />

Generation and the Military<br />

By Capt. David Dixon<br />

Page 21<br />

In Mideast Conflicts, at What<br />

Price Victory?<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, USA Ret.<br />

Page 22<br />

HE’S THE ARMY......................................26<br />

THE OUTPOST........................................57<br />

SOLDIER ARMED....................................59<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING.....................61<br />

SUSTAINING MEMBER PROFILE ...........64<br />

REVIEWS.................................................65<br />

FINAL SHOT ...........................................72<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

FEATURES<br />

<strong>Army</strong> University: Will Education System<br />

Earn Prestige With Improvements<br />

And a New Name?<br />

By Rick Maze<br />

<strong>Army</strong> University is an ambitious plan to<br />

boost the quality and respect of the<br />

service’s expansive professional education<br />

network with symbolic and substantive<br />

changes. Page 27<br />

Reserve Component Generals: True Professionals<br />

By Brig. Gen. Raymond E. Bell Jr., USA Ret.<br />

General officers of the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Reserve and<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard have<br />

successfully<br />

served for<br />

extended<br />

periods on<br />

active duty in an<br />

array of challenging<br />

positions, including<br />

combat. Page 30<br />

<strong>Stimulating</strong> <strong>Simulation</strong>:<br />

Technology Advances and<br />

Upgrades Boost Realism in<br />

Soldier Training<br />

By Scott R. Gourley<br />

With simulation technologies a<br />

ubiquitous element of modern life, it’s<br />

not surprising that today’s soldiers are<br />

encountering the expanded use of<br />

simulation technologies across the<br />

military experience. Page 36<br />

Cover Photo: Pfc. Shante Sapp, Headquarters<br />

and Headquarters Company,<br />

35th Engineer Brigade, Missouri <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard, uses the Dismounted Soldier<br />

Training System during a virtual training<br />

simulation at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Pfc. Samantha J. Whitehead<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 1

Germany Committed to Common Defense<br />

By Lt. Gen. Jorg Vollmer<br />

The German <strong>Army</strong> chief of staff describes how and why<br />

his country is fully committed to NATO and the<br />

common defense of Germany’s partners. Page 32<br />

32<br />

40<br />

12-Step Plan for Curing a Toxic Team<br />

By Keith H. Ferguson<br />

A toxic team is a group of people who<br />

conspire to work against the direction<br />

desired by leadership. The first step<br />

toward fixing a toxic team is to admit the<br />

problem exists. Page 40<br />

For Brain-Injured Vets,<br />

COMPASS Offers Direction<br />

By Mitch Mirkin<br />

A VA research program called Community<br />

Participation through Self-Efficacy Skills<br />

Development, or COMPASS, is aiding<br />

veterans with brain injuries by teaching<br />

them skills that help them manage their<br />

condition. Page 43<br />

Peer Pressure: Attorney Evaluation<br />

System Might Benefit All Officers<br />

By Col. William M. Connor<br />

An <strong>Army</strong> Reserve officer who is an attorney<br />

in civilian life describes how the legal<br />

profession’s system of peer evaluation<br />

offers an efficient, fair and equitable<br />

alternative for military use. Page 47<br />

47<br />

43<br />

Facebook Embedded in Family Life<br />

By Rebecca Alwine<br />

Military families use Facebook for myriad reasons,<br />

including staying in touch with family and friends,<br />

obtaining up-to-the minute news, and gathering<br />

information to help with transitions and moves.<br />

Page 52<br />

52<br />

Counseling Can Uncover Oppressive Climate<br />

By Capt. Gary M. Klein and 1st Lt. Brock J. Young<br />

Regular counseling not only builds trust but can also<br />

uncover command climate issues. Page 54<br />

54<br />

49<br />

Reading: The Key to<br />

Critical Thinking<br />

By Lt. Col. C. Richard Nelson, USA Ret.<br />

As part of the process of<br />

connecting ends and means,<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leaders must be broadly<br />

educated and read accordingly—<br />

beyond briefing books prepared<br />

by their staffs. Page 49<br />

2 ARMY ■ March 2016

Letters<br />

A Fight We Can’t Afford to Lose<br />

■ Usually, in boxing, a one-two punch<br />

is good for a knockout, but the one-twothree<br />

punch in the first three articles in<br />

the Front & Center section of the January<br />

issue should certainly foster a wakeup.<br />

Retired Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen<br />

(“America: Step Up, Wake Up, Wise<br />

Up”), Emma Sky (“What Lessons<br />

Should We Take From the Iraq War?”)<br />

and retired Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano<br />

(“Syria Operations Sending All the<br />

Wrong Signals”) put in perspective the<br />

absolutely critical situation that faces<br />

our country, the dangers thereof, and<br />

the tough road to recovery. Such discussions<br />

are long overdue and, unfortunately,<br />

muted.<br />

I have been around for 93 years and<br />

have seen the results of our lack of preparedness<br />

in two world wars, and I do<br />

not want it to happen again. You have<br />

made a good start with these splendid<br />

articles, but the bugle must be sounded<br />

louder. Please take a deep breath before<br />

the next issue.<br />

Maj. Gen. Chet McKeen, USA Ret.<br />

Fort Worth, Texas<br />

Recruiting Saw Many Changes<br />

■ In his January article, “Let’s Solve<br />

the <strong>Army</strong>’s Recruiting Challenges,” retired<br />

Col. Bob Phillips omits mention of<br />

a third advertising campaign that preceded<br />

Maj. Gen. Maxwell R. Thurman’s<br />

arrival as head of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Recruiting<br />

Command. Recruiting always gets<br />

tougher when the economy improves and<br />

inevitably, advertising is looked to as a<br />

partial solution. I was deputy director of<br />

advertising and sales promotion for Recruiting<br />

Command from June 1973 until<br />

January 1993 and believe knowledge of<br />

earlier hits and misses can be helpful to<br />

those now in charge of using advertising<br />

to help provide the strength.<br />

The advertising program effectively<br />

began in 1971 with a campaign designed<br />

to make young people rethink traditional<br />

objections to <strong>Army</strong> life. The slogan “Today’s<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Wants to Join You” suggested<br />

a kindlier welcoming than the average<br />

new recruit was liable to encounter,<br />

and aspirations of the <strong>Army</strong>’s Modern<br />

Volunteer <strong>Army</strong> office that were never<br />

widely implemented were publicized.<br />

Old soldiers saw it as a threat to good<br />

order and discipline. Civilian critics wondered<br />

if it was a misrepresentation. It was<br />

pulled after two years and replaced with<br />

“Join the People Who’ve Joined the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>,” which ran until 1978. That it did<br />

so without controversy was mostly because<br />

lessons learned with the earlier<br />

campaign had been taken to heart by the<br />

advertising agency and <strong>Army</strong> officials responsible<br />

for approving the ads, but also<br />

because it was less visible. “Today’s <strong>Army</strong>”<br />

had burst on the scene with a major television<br />

buy, but Congress kept <strong>Army</strong> advertising<br />

off TV, the most intrusive (and<br />

effective) medium, from 1973 to 1978.<br />

Then, <strong>Army</strong> recruiting was put on the<br />

defensive by a congressional staff report<br />

containing quotes by soldiers in Europe<br />

alleging lies by recruiters and misleading<br />

impressions in the advertising. The contract<br />

advertising agency, N.W. Ayer, addressed<br />

the problem by creating the<br />

“This is the <strong>Army</strong>” campaign, which<br />

promised a “warts and all” view of <strong>Army</strong><br />

service. This approach was welcomed in<br />

the Pentagon and the halls of Congress<br />

but found few fans among struggling recruiters,<br />

who observed that some of the<br />

“warts” were mainly helpful to their<br />

competitors in the other services.<br />

This was the advertising that Thurman<br />

found when he arrived at Recruiting<br />

Command. In an early meeting, he<br />

told agency executives he wanted it replaced<br />

with something more upbeat to<br />

match the many changes in recruiting he<br />

was about to introduce. They outlined,<br />

and he approved, an approach that entailed<br />

best industry practices and catered<br />

to his formidable analytical demands.<br />

Unlike his predecessors in command, he<br />

took an intense interest in the yearlong<br />

process, reviewing progress in grueling<br />

monthly sessions and educating the<br />

agency in important aspects of the “product,”<br />

notably the <strong>Army</strong> modernization<br />

program that would make credible the<br />

copy line: “In the <strong>Army</strong>, the Cavalry flies,<br />

the Infantry rides, and the Artillery can<br />

hit a fly in the eye 15 miles away.”<br />

The somewhat dispirited recruiters<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> National Guard/1st Lt. Jessica Donnelly<br />

Members of the South Carolina <strong>Army</strong> National Guard graduate from the Recruit Sustainment Program.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 3

Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, USA Ret.<br />

President and CEO, AUSA<br />

Lt. Gen. Guy C. Swan III, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Education, AUSA<br />

Rick Maze<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Liz Rathbun Managing Editor<br />

Joseph L. Broderick Art Director<br />

Ferdinand H. Thomas II Sr. Staff Writer<br />

Toni Eugene<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Christopher Wright Production Artist<br />

Laura Stassi Assistant Managing Editor<br />

Thomas B. Spincic Assistant Editor<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.;<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.; Lt.<br />

Gen. Daniel P. Bolger, USA Ret.; and<br />

Brig. Gen. John S. Brown, USA Ret.<br />

Contributing Writers<br />

Scott R. Gourley and Rebecca Alwine<br />

Lt. Gen. Jerry L. Sinn, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Finance and<br />

Administration, AUSA<br />

Desiree Hurlocker<br />

Advertising Production and<br />

Fulfillment Manager<br />

ARMY is a professional journal devoted to the advancement<br />

of the military arts and sciences and representing the in terests<br />

of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>. Copyright©2016, by the Association of<br />

the United States <strong>Army</strong>. ■ ARTICLES appearing in<br />

ARMY do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the officers or<br />

members of the Council of Trustees of AUSA, or its editors.<br />

Articles are expressions of personal opin ion and should not<br />

be interpreted as reflecting the official opinion of the Department<br />

of Defense nor of any branch, command, installation<br />

or agency of the Department of Defense. The magazine<br />

assumes no responsibility for any unsolicited material.<br />

■ ADVERTISING. Neither ARMY, nor its pub lisher,<br />

the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>, makes any representations,<br />

warranties or endorsements as to the truth and<br />

accuracy of the advertisements appearing herein, and no<br />

such representations, warranties or endorsements should be<br />

implied or inferred from the appearance of the advertisements<br />

in the publication. The advertisers are solely responsible<br />

for the contents of such advertisements.<br />

■ RATES. Individual membership fees payable in advance<br />

are $30 for two years, $50 for five years, and $300 for Life<br />

Membership, of which $9 is allocated for a subscription to<br />

ARMY magazine. A discounted rate of $10 for two years is<br />

available to members in the ranks of E-1 through E-4, and for<br />

service academy and ROTC cadets and OCS candidates. Single<br />

copies of the magazine are $3, except for a $20 cost for the<br />

special October Green Book. More information is available at<br />

our website www.ausa.org; or by emailing membersupport<br />

@ausa.org, phoning 855-246-6269, or mailing Fulfillment<br />

Manager, P.O. Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

got a preview of the new campaign in<br />

mid-December 1980, a few weeks before<br />

the first commercials aired, in the form<br />

of a short film that began with Thurman<br />

outlining his vision for the recruiting future<br />

and proceeding to display the first<br />

two TV spots. They tolerated the lecture<br />

and applauded the commercials. Spirits<br />

all around were lifted when jingle writer<br />

Jake Holmes was heard singing the little<br />

anthem he had composed, scored and<br />

recorded over a weekend after the winning<br />

slogan had been chosen.<br />

“Be All You Can Be” evolved over the<br />

next 20 years—a long run for an ad campaign—and<br />

played an important part in<br />

recruiting success. In its millennial issue,<br />

Advertising Age ranked it No. 18 among<br />

the best 100 ad campaigns of the 20th<br />

century.<br />

But the <strong>Army</strong> is given a large advertising<br />

budget for finding the very best way<br />

to convince young people they should<br />

meet with a recruiter. That must remain<br />

the main focus of the effort.<br />

Capt. Thomas W. Evans,<br />

U.S. Naval Reserve retired<br />

Mundelein, Ill.<br />

AUSA FAX NUMBERS<br />

ARMY magazine welcomes letters to<br />

the editor. Short letters are more<br />

likely to be published, and all letters<br />

may be edited for reasons of style,<br />

accuracy or space limitations. Letters<br />

should be exclusive to ARMY magazine.<br />

All letters must include the<br />

writer’s full name, address and daytime<br />

telephone num ber. The volume<br />

of letters we receive makes individual<br />

acknowledgment impossible. Please<br />

send letters to The Editor, ARMY magazine,<br />

AUSA, 2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington,<br />

VA 22201. Letters may also<br />

be faxed to 703- 841-3505 or sent via<br />

email to armymag@ausa.org.<br />

Take Mideast Warnings to Heart<br />

■ It was interesting to find the sharp<br />

contrast in the Middle East perspectives<br />

of Emma Sky, director of Yale World<br />

Fellows, and retired Lt. Col. James Jay<br />

Carafano, a Heritage Foundation vice<br />

president, in the January issue of ARMY<br />

magazine.<br />

In “What Lessons Should We Take<br />

From the Iraq War?” Sky stated that she<br />

was opposed to the 2003 Iraq War and<br />

then without specifying blame, succinctly<br />

wrote a factual sequence of the events<br />

and consequences. She then provided insightful<br />

suggestions that are conducive to<br />

discussion and reflection.<br />

Carafano wrote an exceedingly critical<br />

critique of U.S. involvement in the Middle<br />

East in “Syria Operations Sending<br />

All the Wrong Signals.” The focus and<br />

target of his criticism was specific, with<br />

over a dozen references to President<br />

Barack Obama and “the administration.”<br />

Carafano referenced the leadership styles<br />

of eight presidents, starting with George<br />

Washington and ending with Ronald<br />

Reagan, but neglected to mention the<br />

administration that passed on to Obama<br />

two active wars and an economy that was<br />

in the greatest recession since the Great<br />

Depression.<br />

It is a complex world. It is my hope<br />

that all commanders in chief, in concert<br />

with the American people, will take<br />

Sky’s warning to heart: “If we don’t learn<br />

anything from the Iraq War, then all<br />

that sacrifice, all that loss of blood and<br />

treasure, will have been for nothing.”<br />

Col. Tyrone L. Steen, AUS Ret.<br />

Colorado Springs, Colo.<br />

ADVERTISING. Information and rates available<br />

from AUSA’s Advertising Production Manager or:<br />

Andrea Guarnero<br />

Mohanna Sales Representatives<br />

305 W. Spring Creek Parkway<br />

Bldg. C-101, Plano, TX 75023<br />

972-596-8777<br />

Email: andreag@mohanna.com<br />

ARMY (ISSN 0004-2455), published monthly. Vol. 66, No. 3.<br />

Publication offices: Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201-3326, 703-841-<br />

4300, FAX: 703-841-3505, email: armymag@ausa.org. Visit<br />

AUSA’s website at www.ausa.org. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

Arlington, Va., and at additional mailing office.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ARMY Magazine,<br />

Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

703-236-2929<br />

Institute of Land<br />

Warfare,<br />

Senior Fellows<br />

703-243-2589<br />

Industry Affairs<br />

703-841-3505<br />

ARMY Magazine,<br />

AUSA News,<br />

Communications<br />

703-841-1442<br />

Administrative<br />

Services<br />

703-841-1050<br />

Executive Office<br />

703-841-5101<br />

Information<br />

Technology<br />

703-236-2927<br />

Regional Activities,<br />

NCO/Soldier<br />

Programs<br />

703-525-9039<br />

Finance,<br />

Accounting,<br />

Government<br />

Affairs<br />

703-236-2926<br />

Education,<br />

Family<br />

Programs<br />

703-841-7570<br />

Marketing,<br />

Advertising,<br />

Insurance<br />

4 ARMY ■ March 2016

Seven Questions<br />

Scarce Resource for Soldiers: Good Night’s Sleep<br />

Lt. Col. Ingrid Lim is the sleep lead for the <strong>Army</strong>’s Performance<br />

Triad Division, System for Health Directorate.<br />

1. When did the <strong>Army</strong> start studying soldiers’ sleep, and why?<br />

There is a long tradition of sleep research going back to the<br />

1950s at the Walter Reed <strong>Army</strong> Institute of Research looking<br />

at sleep deprivation, fatigue modeling,<br />

and the impact of various patterns of<br />

sleep restriction on cognitive performance.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> recognized that sleep<br />

is a valuable resource. Scientific studies<br />

and tools are required to optimize soldiers’<br />

performance.<br />

The current interest in studying clinical<br />

sleep disorders with soldiers came to<br />

the forefront recently for several reasons.<br />

Sleep is markedly disturbed from wounds<br />

sustained in combat such as traumatic<br />

brain injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder,<br />

and orthopedic injuries with associated<br />

pain. Further, the operational tempo<br />

of combat operations was such that soldiers<br />

frequently obtained insufficient<br />

sleep and lacked standard education on<br />

sleep management and countermeasures.<br />

2. What have been some of the major<br />

findings about soldiers’ sleep habits?<br />

Overall, it is fairly common for soldiers to forgo sleep for military<br />

duties, poor sleep practices, or the inappropriate perception<br />

that sleeping is for lazy or weak individuals.<br />

Texting, watching television or using the computer before<br />

bed, or not having a bedtime routine, add to the challenges of<br />

obtaining healthy sleep. Excessive caffeine intake from energy<br />

drinks, sodas and coffee also plays a role. … Soldiers who perform<br />

non-daytime duties may choose to spend time with their<br />

family instead of sleeping.<br />

3. What methods does the <strong>Army</strong> use to study sleep?<br />

Traditional methods used in a sleep lab include observation;<br />

actigraphy [continuous monitoring by means of a body-worn<br />

device, often on the wrist] and polysomnography [recording of<br />

brain waves, oxygen levels in the blood, heart rate and breathing,<br />

and eye and leg movements]. Sleep is also studied based on<br />

self-report questionnaires regarding various aspects such as<br />

sleep quality and duration.<br />

4. What are some of the next steps planned as a result of the<br />

findings?<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Research and Materiel Command, the<br />

Walter Reed <strong>Army</strong> Institute of Research, and the Biotechnology<br />

High Performance Computing Software Applications Institute<br />

are developing tools for individual soldiers and units to<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Lt. Col. Ingrid Lim<br />

help them better manage fatigue and implement sleep-management<br />

strategies down to the squad level. The <strong>Army</strong> is also<br />

determining ways to prevent sleep loss, identify sleep problems<br />

and sleep disorders, and optimally treat and manage sleep disorders<br />

in soldiers.<br />

Despite increased awareness regarding the importance of<br />

sleep, it is clear that further education is<br />

required on the health and performance<br />

benefits of sleep—education that will lead<br />

to recommendations for <strong>Army</strong> policies<br />

that establish appropriate guidelines for<br />

sleep duration in soldiers, as well as safetyrelated<br />

policies when adequate sleep is not<br />

obtained.<br />

5. What have the Iraq and Afghanistan<br />

wars shown us about sleep?<br />

The wars have demonstrated the effectiveness<br />

of sleep-management planning.<br />

When soldiers are provided with guidance<br />

on appropriate sleep management,<br />

they tend to get better sleep and perform<br />

their military duties better. A soldier who<br />

sleeps well is more resilient.<br />

6. What partnerships has the <strong>Army</strong><br />

formed in the study of sleep?<br />

We currently have several partnerships<br />

both within and outside of the <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

and are working to proliferate sleep knowledge that is intuitively<br />

easy to access. The Office of the Surgeon General recently<br />

hosted a Sleep Summit with representation from major<br />

<strong>Army</strong> commands; civilian and <strong>Army</strong> scientists; clinicians; and<br />

academics from Harvard University, the University of Pittsburgh,<br />

the University of Virginia and RAND Corp. This collection<br />

of renowned sleep experts not only identified specific<br />

sleep priorities within the <strong>Army</strong> but developed a way forward to<br />

accomplish these priorities.<br />

7. Can you predict what sleep science will look like in the<br />

coming years?<br />

As Yogi Berra once observed, “Predictions are hard, especially<br />

about the future.” It is likely that the future of sleep research<br />

will include an increased focus on the long-term effects of<br />

sleep loss on health and an ever-expanding array of issues such<br />

as post-traumatic stress disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer<br />

and autoimmune disorders; the short-term negative consequences<br />

of sleep loss and the positive effects of sleep enhancement<br />

and/or supplementation on resilience to both psychological<br />

and physical trauma; and the increased development and<br />

improvement of technologies that can maximize soldiers’ alertness,<br />

performance, health and well-being.<br />

—Thomas B. Spincic<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 5

Washington Report<br />

Commission: Rough Terrain Ahead for <strong>Army</strong><br />

The final report of the National Commission on the Future<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong> fuels a growing concern in Washington, D.C.,<br />

that the <strong>Army</strong> and the nation could be in trouble and without<br />

any short-term fixes.<br />

“Even with budgets permitting a force of 980,000, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

faces significant shortfalls,” the report says, adding that current<br />

and planned “aviation assets cannot meet<br />

expected wartime capacity requirements.”<br />

There are no short-range air defense<br />

battalions in the Regular <strong>Army</strong>, and many<br />

assets in the National Guard are dedicated<br />

to protecting the nation’s capital, “leaving<br />

precious little capability for other global<br />

contingencies, including high-threat areas<br />

in northeast Asia, southwest Asia, Eastern<br />

Europe or the Baltics,” the report says.<br />

Shortfalls also exist in military police,<br />

field artillery, fuel distribution, water purification,<br />

missile defense, tactical mobility<br />

and watercraft; and with chemical, biological,<br />

radiological and nuclear capabilities.<br />

“Remedying these shortfalls within a<br />

980,000-soldier <strong>Army</strong> will require hard<br />

choices and difficult trade-offs,” the report says.<br />

Retired <strong>Army</strong> Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, president and CEO<br />

of the Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>, said he believes the report<br />

“provides a rare opportunity to address risky capability<br />

shortfalls, reinforce the Total Force concept, and convince a<br />

skeptical Congress and American public there are limits to<br />

how small the <strong>Army</strong> should shrink.”<br />

The commission, headed by retired Gen. Carter F. Ham,<br />

was established by the National Defense Authorization Act for<br />

Fiscal Year 2015. It was tasked with examining the size and<br />

force structure of the <strong>Army</strong>’s active and reserve components.<br />

For political and budgetary reasons, the report says it is “unlikely,<br />

at least for the next few years,” for the <strong>Army</strong> to have<br />

combined active, <strong>Army</strong> Guard and <strong>Army</strong> Reserve forces of<br />

more than 980,000 soldiers. The smart course may be to take<br />

two infantry brigade combat teams out of the Regular <strong>Army</strong> to<br />

free active-duty space for the expanded manning of aviation,<br />

short-range air defense and other capabilities in short supply.<br />

Shifting soldiers doesn’t solve all of the problems, the report<br />

says. “Even if end-strength constraints can be met, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

will need significant additional funding,” it says. The <strong>Army</strong> will<br />

be in a better position to ask for and receive money if it works<br />

with DoD, the White House and Congress on cost-cutting initiatives<br />

to reduce redundancies and improve efficiency. These efforts<br />

“will not be enough” to pay for everything. “Added funding<br />

will eventually be needed if major shortfalls are to be eliminated.”<br />

The other members of the panel were retired Sgt. Maj. of<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> Raymond F. Chandler III; retired Gens. Larry R.<br />

Ellis and James D. Thurman; retired Lt. Gen. Jack C. Stultz;<br />

Thomas R. Lamont, a former assistant secretary of the <strong>Army</strong>;<br />

Robert F. Hale, a former undersecretary of defense; and<br />

Kathleen H. Hicks of the Center for Strategic and International<br />

Studies.<br />

“Although the commission acknowledges<br />

the impossibility of precisely predicting<br />

the future, the commission is certain<br />

that U.S. leaders will face a variety of simultaneous,<br />

diverse threats to our national interests<br />

from both state and non-state actors<br />

as well as natural and man-made disasters,”<br />

the report says.<br />

The commissioners also warn against any<br />

deeper cuts. A total force of 980,000 uniformed<br />

personnel “is the minimum sufficient<br />

force necessary to meet the challenges<br />

of the future strategic environment,” the report<br />

says, listing six things the <strong>Army</strong> could<br />

emphasize to be better ready to tackle the<br />

unknown:<br />

■ Adaptive and flexible leaders are<br />

needed to respond to new technology and unanticipated enemy<br />

action. “<strong>Army</strong> leaders will need to adapt available capabilities<br />

and technology to unexpected missions,” the report says.<br />

■ Cyber capabilities need to be improved “due to the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>’s increasing reliance on computer networks and the<br />

growth of cyber capabilities by state and non-state actors.”<br />

■ Capabilities need to be expanded for urban warfare and<br />

operations in big cities.<br />

■ Flexible and smaller unit formations are needed for future<br />

operations.<br />

■ Defenses against air, rocket and missile attacks need to be<br />

improved.<br />

■ More investment is needed in “game-changing technologies,”<br />

and also in preparing leaders to know how to exploit the<br />

new technologies to the fullest advantage.<br />

A crucial part of the report deals with relations between the<br />

Regular <strong>Army</strong> and the reserve components, a situation soured<br />

by tight budgets that have caused competition for resources<br />

and attention. The commission has a novel idea for having<br />

everyone get along, proposing a pilot program that would integrate<br />

recruiting of active, <strong>Army</strong> National Guard and <strong>Army</strong><br />

Reserve forces into a single effort. This might result in the<br />

components better understanding each other, and may also<br />

save money.<br />

A tight budget led the <strong>Army</strong> to cancel combat-training rotations;<br />

as a result, four <strong>Army</strong> National Guard units were not<br />

deployed overseas in 2013, the report notes.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 7

News Call<br />

U.S. Air National Guard/Master Sgt. Toby Valadie<br />

Weather, Events Keep National Guard Busy<br />

From helping people deal with extreme<br />

weather to providing security for<br />

the visiting pope and other special events<br />

in the U.S., 2015 was a busy year for the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National Guard. And 2016 is<br />

keeping pace.<br />

Extreme weather alone made 2015<br />

the National Guard’s busiest year since<br />

2011, but the start of 2016 suggested it<br />

might equal or even eclipse 2015 in<br />

terms of weather conditions requiring<br />

National Guard assistance, with a historic<br />

blizzard blanketing the mid-Atlantic<br />

states and a shift in the El Nino<br />

weather pattern bringing record rain<br />

and historic flooding to states from California<br />

to Louisiana.<br />

“On average, about 1,500 Guard<br />

members were on duty each day” in 2015,<br />

said Gen. Frank J. Grass, chief of the<br />

National Guard Bureau.<br />

In January, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder<br />

activated his state’s National Guard<br />

to distribute drinking water and filters to<br />

the residents of Flint, a city with a population<br />

of about 100,000. The city had<br />

switched its supply source from Lake<br />

Huron water treated by the Detroit Water<br />

and Sewerage Department to Flint<br />

River water treated at the Flint water<br />

treatment plant. The plant did not add<br />

corrosion-control chemicals to the water<br />

A stuck ambulance gets help from Maryland <strong>Army</strong> National Guard troops during Winter Storm Jonas.<br />

and it was rendered undrinkable when it<br />

was contaminated by lead leaching into<br />

it from pipes and fixtures.<br />

The National Guard manned five distribution<br />

sites at fire stations in Flint,<br />

and was planning to stay active as long as<br />

necessary.<br />

Also in January, Winter Storm Jonas<br />

dropped more than 2 feet of snow and<br />

packed 70 mph wind gusts in the mid-<br />

Atlantic region, closing the federal government<br />

as well as local governments<br />

and hundreds of schools for days. Governors<br />

from 11 states including Georgia,<br />

North Carolina, New York and<br />

New Jersey called up more than 2,200<br />

National Guard personnel. The soldiers<br />

transported medical patients and<br />

providers and helped transport emergency<br />

responders to their calls.<br />

The year 2015 began with snowstorms<br />

smothering the South and Midwest<br />

while Western forests burned to the<br />

ground. Storms raged through Massachusetts,<br />

Virginia and Tennessee. Spring<br />

brought a record fire season in states<br />

from North Dakota to New York, and<br />

more flooding in Texas and Oklahoma.<br />

In September, National Guard units<br />

in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey<br />

and Washington, D.C., helped provide<br />

security and traffic assistance for Pope<br />

Francis’s visit. National Guard members<br />

from several other states including<br />

West Virginia, Massachusetts, Alaska,<br />

With flooding expected in January, soldiers from<br />

the Louisiana <strong>Army</strong> National Guard repair a levee.<br />

Maryland <strong>Army</strong> National Guard<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 9

Kentucky, Delaware, Nebraska, Maryland<br />

and California also supported the<br />

mission.<br />

As 2015 ended, National Guard soldiers<br />

from New Mexico to Missouri<br />

were still cleaning up snow, transporting<br />

patients to doctors, and fighting flooding.<br />

More than 600 members of the<br />

Missouri National Guard assisted emergency<br />

responders in that state. Then, a<br />

series of record storms dropped snow<br />

and rain on California, sparking flash<br />

floods and mudslides.<br />

The El Nino phenomenon, when the<br />

central Pacific Ocean warms, disrupted<br />

established weather patterns around the<br />

world. Meteorologists have rated the<br />

current El Nino as strong as the one that<br />

occurred in 1997–98, when California<br />

and Southern states were deluged and<br />

the Northern half of the country suffered<br />

record-breaking cold.<br />

Report: Delaying Modernization<br />

Leads to Higher Price Tags<br />

A new report about the affordability of<br />

military modernization programs projects<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> will increase weapons<br />

spending 28 percent by fiscal year 2022,<br />

with an increase in spending on ground<br />

systems but a “sharp reduction” in aircraft.<br />

The Center for Strategic and International<br />

Studies report, by analyst Todd<br />

Harrison, discusses the so-called “bow<br />

wave” effect of constantly delaying weapons<br />

modernization, resulting in the cumulative<br />

price tag slowly rising. “The<br />

modernization bow wave cannot be pushing<br />

into the future indefinitely,” Harrison<br />

warns in “Defense Modernization Plans<br />

Through the 2020s: Addressing the Bow<br />

Wave.” “Difficult choices lie ahead if the<br />

modernization bow wave proves too<br />

steep to climb,” he writes.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> acquisition funding is low because<br />

of the cancellation of the Future<br />

Combat Systems and the Ground Combat<br />

Vehicle, and the winding down of<br />

building MRAPs, Harrison writes. Now,<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> is ramping up funding for five<br />

major vehicle programs over the next five<br />

years and modernizing several communications<br />

systems. The Joint Light Tactical<br />

Vehicle program is the largest program,<br />

with production expected through fiscal<br />

year 2040 at a rate of about 2,200 vehicles<br />

a year.<br />

SoldierSpeak<br />

On Challenges<br />

“I distinctly remember challenging myself to work harder, to be as fast or as<br />

strong or as skilled or as smart as many of you. It was a healthy competition that inspired<br />

me to be better every single day,” said Brig. Gen. Diana M. Holland upon<br />

assuming command as the first female officer to serve as commandant of cadets at<br />

the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.<br />

On Leading the Pack<br />

“We need resilient, mentally and physically fit soldiers of character who can become<br />

competent, committed, agile and adaptive leaders who can perform for<br />

these cohesive teams of trusted professionals and represent the diversity of America,”<br />

said Deputy Chief of Staff, G-1, Lt. Gen. James C. McConville during a visit<br />

to Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. “Young people want to be on a team that does important<br />

stuff. They’re the type of soldiers we want in our <strong>Army</strong>.”<br />

On Family Role Models<br />

“I want to feel the same pride and responsibility as my father has shown,” said<br />

Kerrigan B. Head as her dad, a 10th Mountain Division chief warrant officer, swore<br />

her in at a Military Entrance Processing Station in Syracuse, N.Y. “I enlisted in the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> out of all the other branches because I’ve already lived the <strong>Army</strong> life since I<br />

was 3 years old, and I have seen what can be offered to me through the work of my<br />

father. I want to continue my education and create my own adventures.”<br />

On Imagination as Secret Ingredient<br />

“I wish I had these dishes in basic” training, said Pvt. Yorby Fernandez, a culinary<br />

specialist with the 145th Maintenance Company, New York <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard, and a judge in a contest for Hudson Valley high school students to<br />

turn randomly chosen MRE components into creative, tasty meals complete with<br />

drink and dessert. “They did an amazing job,” Fernandez said.<br />

On Being Prepared<br />

“The worst thing you can ever do in any situation is not do anything at all,” said<br />

Spc. Jake Planatscher, a medic with the 705th Military Police Detention Battalion,<br />

Fort Leavenworth, Kan., who was named a “Hero of the Month” for his<br />

contributions to the Joint Regional Correctional Facility for military inmates.<br />

On Helping Neighbors<br />

“What I’ve enjoyed the most is seeing the reactions from the senior citizens and<br />

all veterans we’ve been helping,” said Pfc. Nestor Renteria when the 717th<br />

Brigade Support Battalion, New Mexico <strong>Army</strong> National Guard, based in<br />

Roswell, helped fellow residents and local emergency services recover after a<br />

historic blizzard crippled the town.<br />

On Suicide Intervention<br />

“A person at risk feels like they have nothing to live for,” said Sgt. Charles<br />

Stokes, motor transport operator with the 1st Armored Division, who was recognized<br />

at Fort Bliss, Texas, for successful suicide interventions. “So you have to<br />

help that person find a turning point, a reason to live. You find that from hearing<br />

out their story.”<br />

On Unmanned Aerial Systems<br />

“One of the drawbacks is that UAVs can’t get people to come out because they<br />

can’t see them,” said Chief Warrant Officer 3 Jason Richards, a Kiowa pilot with<br />

the 82nd Airborne Division, during the helicopter’s last rotation at Fort Polk, La.<br />

“They see us and we scare them, and that forces them to come out and fight, then<br />

we shoot them.”<br />

10 ARMY ■ March 2016

GENERAL OFFICER CHANGES*<br />

Maj. Gen. M.A.<br />

Bills from CG, 1st<br />

Cavalry Div., Fort<br />

Hood, Texas, to<br />

Asst. CoS, C-3/J-3,<br />

UNC/CFC/USFK,<br />

ROK.<br />

Maj. Gen. J.C.<br />

Thomson III from<br />

Cmdt. of Cadets,<br />

USMA, West Point,<br />

N.Y., to CG, 1st<br />

Cavalry Div., Fort<br />

Hood.<br />

Brigadier Generals: P. Bontrager from Cmdr.,<br />

TAAC-S, RSM, NATO, OFS, Afghanistan, to Dep.<br />

CG, 10th Mountain Div. (Light) and Acting Senior<br />

Cmdr., Fort Drum, N.Y.; D.M. Holland<br />

from Dep. CG, Spt., 10th Mountain Div., Fort<br />

Drum, to Cmdr. of Cadets, USMA.<br />

■ CG—Commanding General; CoS—Chief of<br />

Staff; OFS—Operation Freedom’s Sentinel;<br />

ROK—Republic of Korea; RSM—Resolute Support<br />

Mission; Spt.—Support; TAAC-S—Train Advise<br />

Assist Cmd.-South; UNC/CFC/USFK—United<br />

Nations Cmd./Combined Forces Cmd./U.S. Forces<br />

Korea; USMA—U.S. Military Academy.<br />

*Assignments to general officer slots announced<br />

by the General Officer Management Office, Department<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong>. Some officers are listed at<br />

the grade to which they are nominated, promotable<br />

or eligible to be frocked. The reporting<br />

dates for some officers may not yet be determined.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Fatalities in Iraq<br />

The following U.S. <strong>Army</strong> soldier<br />

died supporting Operation Inherent<br />

Resolve from Jan. 1-31. His<br />

name was released through DoD;<br />

his family has been notified.<br />

Sgt. Joseph F. Stifter, 30<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Fatalities in Afghanistan<br />

The following U.S. <strong>Army</strong> soldier<br />

died supporting Operation Freedom’s<br />

Sentinel from Jan. 1–31.<br />

His name was released through<br />

DoD; his family has been notified.<br />

Staff Sgt. Matthew Q. McClintock,<br />

30<br />

Also in development is the Armored<br />

Multi-Purpose Vehicle, a replacement<br />

for the Paladin 155 mm self-propelled<br />

artillery, upgrading Abrams tanks, and<br />

improvements in Bradley Infantry Fighting<br />

Vehicles. “Together these programs<br />

will increase funding for the <strong>Army</strong>’s major<br />

ground systems learning threefold between<br />

FY 2015 and FY 2021,” Harrison<br />

writes.<br />

Aviation funding is declining, Harrison<br />

says, because several major aircraft<br />

programs are ending, including the MQ-<br />

1C Grey Eagle, CH-47F Chinook,<br />

AH-64E Apache and UH-60M Black<br />

Hawk. The <strong>Army</strong> is still spending on<br />

aviation procurement, with upgraded<br />

turbine engines for the Apache and<br />

Black Hawk helicopters and development<br />

of vertical lift helicopters.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> is just a small part of acquisition<br />

expansion, Harrison says, noting<br />

there are 120 major programs underway<br />

or planned to start in the next 15 years,<br />

not including classified programs.<br />

‘Health of the Force’ Report<br />

Prescribes Performance Progress<br />

Active-duty soldiers could greatly improve<br />

their personal performance—and<br />

with it the <strong>Army</strong>’s readiness—by getting<br />

more sleep, increasing their physical activity,<br />

and eating healthier foods, according<br />

to the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Command.<br />

The first-of-its-kind report, called<br />

Health of the Force, tracks chronic disease,<br />

obesity, tobacco use and numerous other<br />

health factors as well as the Performance<br />

Triad of sleep, physical activity and nutrition<br />

to create a snapshot of soldiers’<br />

health across 30 major installations.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> focuses on the Performance<br />

Triad, or P3, as a way to proactively promote<br />

health and prevention instead of<br />

dealing with chronic problems that develop<br />

over time. Given 100 as a perfect<br />

P3 score, the <strong>Army</strong> targeted 85 as an acceptable<br />

score for soldiers. No installation<br />

made the cut. They averaged 67 in<br />

sleep, 81 in activity, and 69 in nutrition.<br />

The lack of any one of the three critical<br />

factors has a major impact on <strong>Army</strong><br />

readiness. More than a third of newly accessioned<br />

soldiers fail to complete their<br />

first enlistment term. About 17 percent<br />

of active-duty soldiers cannot be medically<br />

ready to deploy with three days’<br />

notice; simple failure to keep up with<br />

dental and medical checkups accounts<br />

for one-third of that number. Each<br />

month, some 1,400 soldiers are unavailable<br />

to deploy due to medical factors.<br />

According to the report, which uses<br />

2014 data and was released in December,<br />

78,000 soldiers are clinically obese,<br />

and it costs the <strong>Army</strong> more than<br />

$75,000 per new recruit to replace soldiers<br />

discharged due to weight control.<br />

Briefs<br />

Driverless <strong>Army</strong> Trucks Appear<br />

At North American Auto Show<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> had an attention-getting<br />

display at the 2016 North American<br />

International Auto Show in Detroit: two<br />

example of driverless technology exhibited<br />

by the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Tank Automotive<br />

Research, Development and Engineering<br />

Center.<br />

There was, of course, a Google autonomous<br />

car at the show, but the <strong>Army</strong><br />

showed off its own driverless vehicles.<br />

They are a Peterbilt Class 8 semitractor<br />

commercial vehicle and an M915, a heavy<br />

truck used for long-distance logistics.<br />

The Warren, Mich.-based <strong>Army</strong> automotive<br />

command has been testing driverless<br />

truck technology for several years.<br />

Rather than starting from scratch, the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has joined in research with commercial<br />

truck manufacturers and automakers<br />

that also see a future in driverless vehicles,<br />

if a few hurdles can be overcome. The<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has been making steady progress in<br />

research, with hopes of fielding the first<br />

driverless convoy around 2025.<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> has had convoys of<br />

self-driving vehicles in testing for years.<br />

Sending driverless vehicles into combat<br />

creates problems that don’t appear on<br />

interstate highways, but the <strong>Army</strong> continues<br />

to explore the possibility of selfdriving<br />

trucks to deliver supplies on humanitarian<br />

missions and resupply some<br />

troops in the field, with the potential of<br />

lower costs and fewer accidents.<br />

Paul D. Rogers, director of the <strong>Army</strong><br />

program, has described driverless vehicles<br />

as a potentially significant safety<br />

measure. That is because many attacks<br />

on soldiers happen along supply routes.<br />

A convoy of driverless vehicles could deliver<br />

the same amount of material as a<br />

convoy with drivers, without concern<br />

about fatigued soldiers or injuries.<br />

First Multicomponent <strong>Army</strong> Unit,<br />

2nd BCT Support Inherent Resolve<br />

The headquarters of 101st Airborne<br />

Division (Air Assault), the first multicomponent<br />

unit in the <strong>Army</strong>, and the<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 11

COMMAND SERGEANTS MAJOR<br />

and<br />

SERGEANTS MAJOR CHANGES*<br />

*Command sergeants major and<br />

sergeants major positions assigned to<br />

general officer commands.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.T. Brady<br />

from U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

WTC to RHC-A (P),<br />

Fort Belvoir, Va.<br />

Sgt. Maj. J. Cecil<br />

from PRMC Ops.,<br />

Honolulu, to MED-<br />

COM G-3/5/7,<br />

Falls Church, Va.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.L. Cosper<br />

from USAG Fort<br />

Hood, Texas, to<br />

JTF-Guantanamo<br />

Bay, Cuba.<br />

Command Sgt. Maj.<br />

V.G. Culp from 7th<br />

Transportation Bde.<br />

(Expeditionary), Fort<br />

Eustis, Va., to U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Transportation<br />

Corps and School,<br />

Fort Lee, Va.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. D. Curry from<br />

311th Signal Cmd.<br />

(T), Fort Shafter,<br />

Hawaii, to NETCOM,<br />

Fort Huachuca, Ariz.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. H.E. Dunn<br />

from 20th CBRNE<br />

Cmd., APG, Md., to<br />

Sgt. Maj., FORSCOM<br />

G-3, Fort Bragg, N.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.C. Luciano<br />

from PRMC, Honolulu,<br />

to DHA, Falls<br />

Church.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. L. Thomas Jr.<br />

from USAR to Sgt.<br />

Maj., Senior Enlisted<br />

Advisor to<br />

the ASD (M&RA).<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. J.P. Wills<br />

from 99th Regional<br />

Support Cmd., JB<br />

McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst,<br />

N.J., to USAR.<br />

■ APG—Aberdeen Proving Ground; ASD (M&RA)—Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs; Bde.—Brigade; CBRNE—Chemical, Biological,<br />

Radiological, Nuclear and Explosives Cmd.; DHA—Defense Health Agency; FORSCOM—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Forces Cmd.; JB—Joint Base; JTF—Joint Task Force; MEDCOM—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Medical Cmd.; NETCOM—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Network Enterprise Technology Cmd.; PRMC—Pacific Regional Medical Cmd.; RHC-A (P)—Regional Health Cmd.-Atlantic<br />

(Provisional); T—Theater; USAG—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Garrison; USAR—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Reserve; WTC—Warrior Transition Cmd.<br />

SENIOR EXECUTIVE SERVICE<br />

ANNOUNCEMENTS<br />

G. Garcia, Tier 2,<br />

from Exec. Dir., ITA,<br />

OAASA, to Dir. for<br />

Corp. Info., Office<br />

of the USACE,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

D. Jimenez, Tier 2,<br />

from Exec. Technical<br />

Dir./Dep. to the<br />

Cmdr., HQ, ATEC,<br />

APG, Md., to Asst.<br />

to the DUSA/Dir. of<br />

Test and Eval., Office<br />

of the DUSA,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Tier 1: G. Kitkowski to Regional Business Dir.,<br />

USACE, Pacific Ocean Div., Fort Shafter, Hawaii.<br />

■ APG—Aberdeen Proving Ground; ATEC—<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Test and Evaluation Cmd.; DUSA—<br />

Deputy Undersecretary of the <strong>Army</strong>; ITA—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Information Technology Agency;<br />

OAASA—Office of the Administrative Assistant<br />

to the Secretary of the <strong>Army</strong>; USACE—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Corps of Engineers.<br />

2nd Brigade Combat Team are deploying<br />

this spring to support Operation Inherent<br />

Resolve and will train Iraqi security<br />

forces in the fight against the Islamic<br />

State group. Last June, about 65 members<br />

of the Wisconsin <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard became part of the 101st’s headquarters,<br />

and in January they boarded<br />

buses to Fort Campbell, Ky., to take part<br />

in predeployment training there.<br />

Joining them at Fort Campbell were<br />

53 intelligence soldiers from the Utah<br />

National Guard who are also part of the<br />

new unit and will provide technical support.<br />

Approximately 500 101st soldiers<br />

complete the headquarters, which is part<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong> initiative to integrate reserve<br />

component soldiers with activeduty<br />

soldiers while increasing specific<br />

areas of expertise or filling gaps in specialties<br />

such as intelligence. The 2nd<br />

BCT will deploy with about 1,300 soldiers;<br />

the deployment is a routine rotation<br />

of nine months.<br />

Secretary of Defense Ash Carter spoke<br />

to the soldiers in January at Fort Campbell.<br />

He outlined an accelerated campaign<br />

against the Islamic State that will include<br />

retaking their headquarters city of Mosul.<br />

The task “will not be easy, and it will not<br />

be quick,” Carter said. “The training you<br />

will provide … will be critical.”<br />

AUSA Simplifies Membership<br />

Fees, Offers 2-Year Discount<br />

The Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> has<br />

announced a new, streamlined membership<br />

fee structure, one that allows new<br />

and renewing members to pay $30 for a<br />

two-year membership and $50 for a fiveyear<br />

membership.<br />

The cost of an AUSA Life membership<br />

is $300. A discounted rate of $10 for two<br />

years is available for E-1s to E-4s (private<br />

through corporal/specialist), and for U.S.<br />

Military Academy and ROTC cadets.<br />

AUSA is a 66-year-old educational<br />

nonprofit organization supporting the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>, including soldiers and civilian<br />

workers, all active and reserve component<br />

members, veterans and retirees, family<br />

members and defense industry partners.<br />

“Now more than ever, America’s <strong>Army</strong><br />

needs AUSA, and AUSA needs your<br />

membership support,” said retired Sgt.<br />

Maj. of the <strong>Army</strong> Kenneth O. Preston,<br />

director of AUSA’s Noncommissioned<br />

Officer and Soldier Programs, noting the<br />

turbulent times facing the <strong>Army</strong> and the<br />

many national security risks facing the<br />

United States.<br />

AUSA hosts national and local programs,<br />

including professional development<br />

forums and exhibitions. Membership includes<br />

subscriptions to the nationally<br />

recognized ARMY magazine and AUSA<br />

News, and weekly email updates about<br />

<strong>Army</strong>-related news and events.<br />

—Stories by Toni Eugene<br />

12 ARMY ■ March 2016

Front & Center<br />

The Risk of Another Unsuccessful War<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

The Jan. 10 New York Times Magazine<br />

article “The Empty Threat of ‘Boots<br />

on the Ground’” raises again the question<br />

of how to fight modern wars, comparing<br />

two “very long, very costly … not<br />

very successful wars”—Iraq and Afghanistan—with<br />

1995, when President Bill<br />

Clinton “managed to end the fighting<br />

in Bosnia … through air power alone.”<br />

Upon reading that, retired Gen. Gordon<br />

Sullivan, president and CEO of the<br />

Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>, added,<br />

“but only when the NATO allies had<br />

fielded a 57,000 NATO implementation<br />

force ready to invade the area.” The air<br />

campaign set the stage and the cease-fire<br />

precluded an immediate combat assault,<br />

but that NATO force then crossed the<br />

Bosnian border, quelled the conflict and<br />

achieved the objectives initially sought.<br />

Final success depended on occupying the<br />

land and controlling the population.<br />

Nevertheless, “boots on the ground”<br />

ever since have had to deal with the perception<br />

that air power such as bombing<br />

and drone strikes can win modern wars.<br />

Boots on the ground promise a return to<br />

long, drawn-out conflicts, serious casualty<br />

rates for both soldiers and civilians,<br />

and inconclusive declarations of mission<br />

accomplishment. The wars in Korea,<br />

Vietnam and Iraq are examples of such<br />

campaigns.<br />

The argument is not new. It began a<br />

century ago when the fledgling air forces<br />

of the World War I Allies demonstrated<br />

long-range bombers, sank a U.S. warship,<br />

then promised that air power could<br />

win World War II. Even after the end of<br />

hostilities in Europe, air power advocates<br />

believed that a few more months of the<br />

air campaign would have negated the<br />

need for the land forces’ D-Day invasion.<br />

Then the atomic bombs ended hostilities<br />

with Japan, but the war objectives<br />

were achieved only during the five years<br />

of occupation that followed.<br />

The land power argument is anchored<br />

on the realization that wars are won<br />

when soldiers occupy terrain, dominate<br />

populations, and achieve the political objectives<br />

of their parent government.<br />

Cease-fires, truces, armistices and even<br />

surrenders do not end wars; only the creation<br />

of new governments or new lasting<br />

allegiances bring finality to the total<br />

campaign. Conquest is the ultimate solution,<br />

but it’s not always the objective.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Spc. Steven Hitchcock<br />

Land power advocates point to World<br />

War II, Operation Just Cause in Panama<br />

and Operation Desert Storm as examples<br />

of when properly organized, manned,<br />

equipped and trained forces ended conflicts<br />

and achieved objectives in good<br />

time and with minimum casualties—<br />

though minimum is a relative term.<br />

Compare, for example, the casualty<br />

count from 1939 to May 1944 with<br />

those of the next year, when land power<br />

forces adequate to the task had been<br />

built and committed.<br />

Resolution of the argument is not imminent,<br />

but an understanding of the<br />

costs, time required and objectives associated<br />

with any contemplated military<br />

campaign is vital in today’s world. The<br />

presidential candidates for our upcoming<br />

election are all being asked about their<br />

solutions for the current Middle East situation.<br />

Their answers offer carpet bombing,<br />

no-fly zones, varying ground force<br />

scenarios, or a continuation of current<br />

actions. None seems to give evidence of<br />

understanding the need to identify the<br />

objectives to be sought, the costs, the<br />

forces necessary, and the time to prepare<br />

for a major effort.<br />

Presidents never ask “Are you ready?”<br />

They should understand that the current<br />

<strong>Army</strong> can respond to a crisis overnight,<br />

but that sustaining a major operation requires<br />

an immediate start to build the total<br />

force essential for the campaign. In<br />

World War II, that took two and a half<br />

years. For the Kuwait liberation, it required<br />

six months to organize the allied<br />

force of more than 500,000 that finished<br />

its combat job in 100 hours. For the Iraq<br />

invasion, when then-<strong>Army</strong> Chief of<br />

Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki expressed a<br />

need for 300,000 soldiers to satisfy the<br />

mission requirements, his recommendation<br />

was rebuffed and the Iraq War<br />

never reached a satisfactory conclusion.<br />

The Afghanistan War is being pursued<br />

in like fashion, and its conclusion will<br />

most likely end in like fashion.<br />

This article is not an effort to influence<br />

a political decision to initiate or<br />

participate in a military campaign in the<br />

Middle East. It is not an attempt to reconcile<br />

the differing views concerning air<br />

and land force campaigns. It is, instead, a<br />

hope that those who generate conceptions<br />

for conducting our next military excursion<br />

will fully consider the costs, the<br />

forces, the sustaining means, the time,<br />

the risks to achieving the objectives desired,<br />

and the pre- and post-activities<br />

that will be required to ensure we will<br />

not be adding another “not very successful<br />

war” to our list.<br />

■<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret., formerly<br />

served as vice chief of staff of the<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> and commander in chief of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe. He is a senior fellow<br />

of AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 13

Definition of ‘Decisive’ Depends on Context<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

Words matter, for they reflect the<br />

quality of thinking and affect the<br />

judgments we make and the actions we<br />

take. In our everyday speech about the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> and what it does, the term “decisive”<br />

is often used as an absolute. For example,<br />

“The <strong>Army</strong> is the decisive force.”<br />

The problem is, decisive is a relative<br />

term in three important and relevant<br />

senses. First, decisive is relative to context;<br />

second, to combinations; and third,<br />

to proper use.<br />

Every branch of service claims it is decisive.<br />

Most of the time in war, though,<br />

each service contributes importantly to<br />

achieving objectives. “Jointness” is the<br />

idea that in any given tactical or operational<br />

situation, a commander should<br />

select the service capabilities necessary<br />

to achieve the objectives assigned, but<br />

these capabilities are only sufficient<br />

when they are combined and employed<br />

properly.<br />

This reminds us all that each service’s<br />

capabilities and the proper employment<br />

of these capabilities are most often necessary,<br />

but not sufficient. Individually,<br />

each can rarely guarantee the outcome,<br />

but together they can. They are decisive<br />

only in properly used combinations.<br />

When the term decisive is used in an<br />

absolute way, it hides the reality of<br />

fighting.<br />

Everything said of jointness is also<br />

true of combined arms warfare. Many<br />

tactical matters are settled only by a<br />

proper mix of direct and indirect fires,<br />

and of fire and maneuver. Further, producing<br />

a definite result in tactical matters<br />

often rests on the quality and use of<br />

intelligence and effective logistics planning<br />

and execution. Fire, maneuver, intelligence<br />

and logistics are each absolutely<br />

necessary, but they are sufficient<br />

only when properly combined.<br />

At this point, many veterans of Iraq<br />

and Afghanistan would be right to point<br />

out that in multiple cases, fighting was<br />

resolved only when kinetic, combined<br />

arms were mixed with nonkinetic action.<br />

In these cases, even properly mixed<br />

combined arms could not be decisive in<br />

the sense of producing a definite result;<br />

depending on the objective, nonkinetic<br />

actions were also necessary.<br />

Simply put, decisiveness is a function<br />

of at least these elements: the level of<br />

war, the type of war, the aim or objective,<br />

and the period of the war. Perhaps<br />

equally important, producing a decisive<br />

result requires not only the right component<br />

capabilities—military and nonmilitary—but<br />

also their proper use. With respect<br />

to decisiveness, the quality of the<br />

decision and its execution matter as much<br />

as having the right parts.<br />

Level of War<br />

Even though complexity and ambiguity<br />

at the tactical level are often quite<br />

high, tactical examples are relatively easy<br />

to grasp. Actions that have decisive results<br />

at the tactical level do not, however,<br />

merely aggregate to the operational<br />

or strategic levels. The art, science and<br />

logic of good tactics are different from<br />

campaigning at the operational level,<br />

and different still at the strategic level of<br />

war. A good tactician is unlikely to succeed<br />

as an operational artist if he or she<br />

merely expands tactical thinking and<br />

procedures to campaigns.<br />

Military campaigns unfold over time.<br />

The dynamic nature of war assures that<br />

the conditions at the start of a campaign<br />

will not be the same as those at the end.<br />

So proper use of a particular campaign’s<br />

elements requires an adaptive decisionmaking<br />

process. Such a process involves<br />

the ability to sense the gap between the<br />

realities unfolding on the battlefield and<br />

the desired outcomes of the campaign,<br />

and then the issuing of instructions to<br />

adapt actions to reality.<br />

A military campaign is designed to attain<br />

part of a strategic aim, or set the<br />

conditions for the attainment of a strategic<br />

aim. So decisiveness at the operational<br />

level may mean not settling a<br />

matter, but producing a definitive result<br />

that, in turn, sets the conditions for<br />

other acts—whether military or not—to<br />

settle an issue.<br />

Decisiveness at the strategic level is<br />

even more difficult. Strategic leaders use<br />

campaigns, but the art, science and logic<br />

of attaining strategic aims are different<br />

from that of campaigning. Settling a war<br />

involves much more than settling a fight.<br />

The elements necessary to produce a decisive<br />

wartime strategic result include,<br />

but are not limited to, military capabilities.<br />

And the proper use of strategic elements<br />

requires information gathering<br />

and analysis, decisionmaking processes<br />

and adaptive methodologies wider than<br />

just military. Further, because war is essentially<br />

dynamic, using existing bureaucracies—inherently<br />

not good at doing<br />

anything new or fast—often decreases<br />

the quality of strategic-level understanding,<br />

deciding, acting and adapting.<br />

Types of War<br />

Decisive actions, or actions that produce<br />

a definitive result and settle a matter<br />

at each level of war, change with the<br />

type of war that is being waged. In a<br />

conventional war, military force—<br />

whether combined arms or joint—can<br />

often be decisive at the tactical and operational<br />

levels. Such a use of force can<br />

settle much of the matter at hand and<br />

set the conditions for complete settlement<br />

at the strategic level. But not all<br />

wars are conventional.<br />

In many irregular wars, military<br />

force—regardless of how skillfully used—<br />

is merely necessary but not sufficient<br />

even at the tactical and operational levels.<br />

In an irregular war, decisive force<br />

takes on an entirely different hue. The<br />

meaning of “force” itself changes to<br />

“forces”; that is, military force becomes<br />

one of many types of forces necessary to<br />

produce a decisive result—diplomatic,<br />

economic and informational forces, for<br />

example. The term “proper use” also<br />

changes. An irregular war requires that<br />

the varieties of forces involved be sufficiently<br />

integrated from the tactical<br />

through the strategic levels because in<br />

irregular war, the levels of understanding,<br />

deciding, acting and adapting differ<br />

from those of conventional wars.<br />

Aim or Objective<br />

Unconditional surrender, the aim relative<br />

to both Germany and Japan in<br />

World War II, differs from the Korean<br />

War’s aim of re-establishing the 38th<br />

Parallel border between North and<br />

14 ARMY ■ March 2016

South Korea. These two aims differ<br />

from enforcing the Dayton Accords in<br />

Bosnia or sustaining a free, democratic<br />

and non-Communist South Vietnam—<br />

and all differ from the aim of destroying<br />

al-Qaida or the Islamic State group. As<br />

military strategist Carl von Clausewitz<br />

explains in On War, “The smaller the<br />

penalty you demand from your opponent,<br />

the less you can expect him to try<br />

and deny it to you; the smaller the effort<br />

he makes, the less you need to make<br />

yourself. … The political object … will<br />

thus determine both the military objective<br />

to be reached and the amount of effort<br />

it requires.”<br />

Producing decisive results—whether<br />

at the tactical, operational or strategic<br />

level—differs according to the war’s aim,<br />

as do the elements necessary to produce<br />

those results. Different aims also require<br />

adjustments to methodologies and organizations<br />

necessary to understand, decide,<br />

act and adapt.<br />

Period of War<br />

Wars have a beginning, middle and<br />

end, and decisiveness changes at each<br />

point. The Iraq War provides a good example.<br />

The actions necessary to produce<br />

decisive results at the beginning of the<br />

war, which was the period focused on<br />

removing the Saddam Hussein regime,<br />

changed when that task was accomplished.<br />

The Surge of 2007–08 provides<br />

another good example. The mix of<br />

forces—military and nonmilitary—that<br />

were tactically and operationally decisive<br />

could not be decisive strategically. Yet<br />

because many leaders equated war with<br />

fighting, the belief was that the war was<br />

over when the fighting seemed to be<br />

mostly over.<br />

This false belief was fed by at least<br />

three intellectual errors: not recognizing<br />

that tactical and operational decisiveness,<br />

in this case, meant only that<br />

the conditions were set for strategic<br />

decisive action; not recognizing that<br />

tactical and operational decisive action<br />

closed the middle of the war, but not<br />

the end; and not recognizing that to<br />

achieve decisive action strategically and<br />

end the war, both the mix of forces and<br />

how they would be used should have<br />

changed.<br />

Having the right mix of military and<br />

nonmilitary forces is one thing; proper<br />

use—in other words, using them well—<br />

is quite another. Whether at the tactical,<br />

operational or strategic level, using forces<br />

involves at least three dimensions.<br />

The first is an intellectual dimension.<br />

Here, the task is to align the objective<br />

with the ways and means that success at<br />

attaining that objective requires. The<br />

second, an organizational dimension,<br />

recognizes that plans have to be turned<br />

into action and thus, includes the need<br />

for proper organizations and methodologies<br />

for understanding, deciding, acting<br />

and adapting. Execution matters,<br />