Is headspace making a difference to young people’s lives?

Evaluation-of-headspace-program

Evaluation-of-headspace-program

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

4. Outcomes of <strong>headspace</strong> Clients<br />

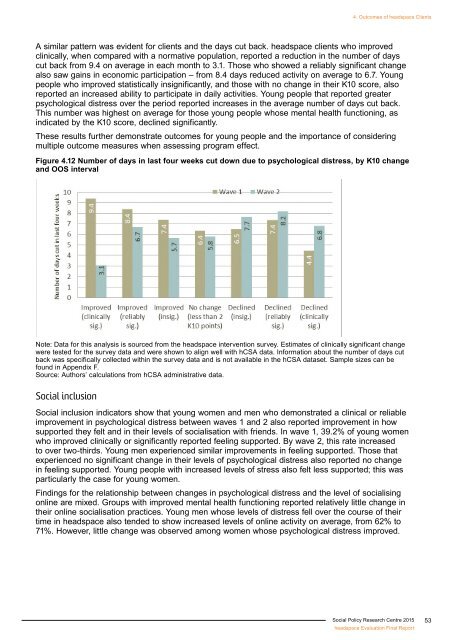

A similar pattern was evident for clients and the days cut back. <strong>headspace</strong> clients who improved<br />

clinically, when compared with a normative population, reported a reduction in the number of days<br />

cut back from 9.4 on average in each month <strong>to</strong> 3.1. Those who showed a reliably significant change<br />

also saw gains in economic participation – from 8.4 days reduced activity on average <strong>to</strong> 6.7. Young<br />

people who improved statistically insignificantly, and those with no change in their K10 score, also<br />

reported an increased ability <strong>to</strong> participate in daily activities. Young people that reported greater<br />

psychological distress over the period reported increases in the average number of days cut back.<br />

This number was highest on average for those <strong>young</strong> people whose mental health functioning, as<br />

indicated by the K10 score, declined significantly.<br />

These results further demonstrate outcomes for <strong>young</strong> people and the importance of considering<br />

multiple outcome measures when assessing program effect.<br />

Figure 4.12 Number of days in last four weeks cut down due <strong>to</strong> psychological distress, by K10 change<br />

and OOS interval<br />

Note: Data for this analysis is sourced from the <strong>headspace</strong> intervention survey. Estimates of clinically significant change<br />

were tested for the survey data and were shown <strong>to</strong> align well with hCSA data. Information about the number of days cut<br />

back was specifically collected within the survey data and is not available in the hCSA dataset. Sample sizes can be<br />

found in Appendix F.<br />

Source: Authors’ calculations from hCSA administrative data.<br />

Social inclusion<br />

Social inclusion indica<strong>to</strong>rs show that <strong>young</strong> women and men who demonstrated a clinical or reliable<br />

improvement in psychological distress between waves 1 and 2 also reported improvement in how<br />

supported they felt and in their levels of socialisation with friends. In wave 1, 39.2% of <strong>young</strong> women<br />

who improved clinically or significantly reported feeling supported. By wave 2, this rate increased<br />

<strong>to</strong> over two-thirds. Young men experienced similar improvements in feeling supported. Those that<br />

experienced no significant change in their levels of psychological distress also reported no change<br />

in feeling supported. Young people with increased levels of stress also felt less supported; this was<br />

particularly the case for <strong>young</strong> women.<br />

Findings for the relationship between changes in psychological distress and the level of socialising<br />

online are mixed. Groups with improved mental health functioning reported relatively little change in<br />

their online socialisation practices. Young men whose levels of distress fell over the course of their<br />

time in <strong>headspace</strong> also tended <strong>to</strong> show increased levels of online activity on average, from 62% <strong>to</strong><br />

71%. However, little change was observed among women whose psychological distress improved.<br />

Social Policy Research Centre 2015<br />

<strong>headspace</strong> Evaluation Final Report<br />

53