Is headspace making a difference to young people’s lives?

Evaluation-of-headspace-program Evaluation-of-headspace-program

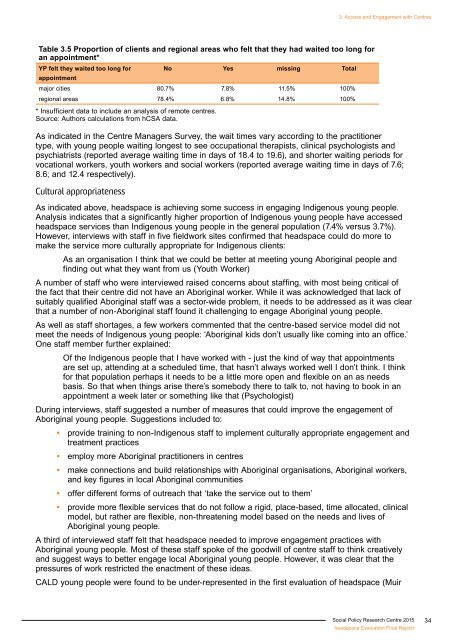

3. Access and Engagement with Centres Table 3.5 Proportion of clients and regional areas who felt that they had waited too long for an appointment* YP felt they waited too long for No Yes missing Total appointment major cities 80.7% 7.8% 11.5% 100% regional areas 78.4% 6.8% 14.8% 100% * Insufficient data to include an analysis of remote centres. Source: Authors calculations from hCSA data. As indicated in the Centre Managers Survey, the wait times vary according to the practitioner type, with young people waiting longest to see occupational therapists, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists (reported average waiting time in days of 18.4 to 19.6), and shorter waiting periods for vocational workers, youth workers and social workers (reported average waiting time in days of 7.6; 8.6; and 12.4 respectively). Cultural appropriateness As indicated above, headspace is achieving some success in engaging Indigenous young people. Analysis indicates that a significantly higher proportion of Indigenous young people have accessed headspace services than Indigenous young people in the general population (7.4% versus 3.7%). However, interviews with staff in five fieldwork sites confirmed that headspace could do more to make the service more culturally appropriate for Indigenous clients: As an organisation I think that we could be better at meeting young Aboriginal people and finding out what they want from us (Youth Worker) A number of staff who were interviewed raised concerns about staffing, with most being critical of the fact that their centre did not have an Aboriginal worker. While it was acknowledged that lack of suitably qualified Aboriginal staff was a sector-wide problem, it needs to be addressed as it was clear that a number of non-Aboriginal staff found it challenging to engage Aboriginal young people. As well as staff shortages, a few workers commented that the centre-based service model did not meet the needs of Indigenous young people: ‘Aboriginal kids don’t usually like coming into an office.’ One staff member further explained: Of the Indigenous people that I have worked with - just the kind of way that appointments are set up, attending at a scheduled time, that hasn’t always worked well I don’t think. I think for that population perhaps it needs to be a little more open and flexible on an as needs basis. So that when things arise there’s somebody there to talk to, not having to book in an appointment a week later or something like that (Psychologist) During interviews, staff suggested a number of measures that could improve the engagement of Aboriginal young people. Suggestions included to: • provide training to non-Indigenous staff to implement culturally appropriate engagement and treatment practices • employ more Aboriginal practitioners in centres • make connections and build relationships with Aboriginal organisations, Aboriginal workers, and key figures in local Aboriginal communities • offer different forms of outreach that ‘take the service out to them’ • provide more flexible services that do not follow a rigid, place-based, time allocated, clinical model, but rather are flexible, non-threatening model based on the needs and lives of Aboriginal young people. A third of interviewed staff felt that headspace needed to improve engagement practices with Aboriginal young people. Most of these staff spoke of the goodwill of centre staff to think creatively and suggest ways to better engage local Aboriginal young people. However, it was clear that the pressures of work restricted the enactment of these ideas. CALD young people were found to be under-represented in the first evaluation of headspace (Muir Social Policy Research Centre 2015 headspace Evaluation Final Report 34

3. Access and Engagement with Centres et al., 2009) and remained so in this evaluation. This suggests that headspace needs to change its engagement and/or treatment practices to better meet the needs of this group. This type of change requires greater understanding of the barriers and facilitators of service access for CALD young people, including the locations of centres relative to areas of higher CALD density, as well as the key issues that affect them. Interviews with headspace staff indicate that this is not a priority area (only 3 of 25 staff members interviewed spoke about CALD young people). Two interviewed workers expressed concern that they were not seeing many young refugees despite being located in an area where this would have been expected. They did, however, not know how to respond to this circumstance: Every now and then we get some clients with some level of language barrier and that have migrated here and are on their own and that sort of thing. Often in that case we do refer to a trans-cultural clinical service because there is that barrier and… we don’t have any interpreters. We don’t get very many of the African communities and we’ve got a lot of African people living locally. Another staff member questioned why CALD young people were not attending headspace: I haven’t had any referrals from non-English speaking backgrounds. Not really any referrals for young people from the various ethnic groups in the area. There’s a lot of Turkish families and there’s African families here now and they’re certainly not any of the young people that I have had referred to me over the time that I’ve been here. So I’m not sure what’s happening there. Although the vulnerability and under-representation of this group was acknowledged by some headspace staff, the majority did not comment on this issue, perhaps suggesting that staff do not know how to respond. Only one staff member suggested community engagement as a strategy for addressing the under-representation of CALD young people as headspace clients. Personal barriers Interviewees identified the mental and cognitive functioning of clients as a barrier to access and sustained engagement with headspace services. A number of young people talked about their reluctance to attend a centre because they were too scared to talk face-to-face to a counsellor. Given that many of the young people who attend the service are dealing with crippling anxiety issues, making initial contact was often described as a huge challenge. The problem is themselves. It’s the going out and seeking help and wanting to get better. The problem is more to do with that than problems with the actual centre. (Male, 18 years) 3.4 How do parents/carers facilitate or hinder young people’s access to and engagement with headspace services? Research has demonstrated that parents can play an important role in facilitating young people’s access to mental health services and help-seeking behaviours (Wahlin & Deane, 2012). As discussed above, 40% of young people reported that they mostly attended headspace because of the influence of family or friends. This was further reinforced in the headspace Parents and Carers Study. Interviews with young people and parents/carers indicate that some young people were encouraged to attend headspace because of the actions of their parents. Six of the 50 young people interviewed (all were female and ranged in age from 13 to 24) described how their mother had made their first appointment with headspace: Mum found [headspace] online and then a few weeks after she made an appointment and I don’t know, I just started going from there… I didn’t even want to go in the first place because I thought that I was okay and there was nothing wrong with me and that mum was just over-reacting to me being upset (Female, 15 years) The Parents and Carers Survey data indicates, however, that while parents employed many Social Policy Research Centre 2015 headspace Evaluation Final Report 35

- Page 1 and 2: Is headspace making a difference to

- Page 3 and 4: Authors This report was written by

- Page 5 and 6: 5. Service Delivery Model 73 5.1 Wh

- Page 7 and 8: Table 6.1 Table 6.2 Table 6.3 Main

- Page 9 and 10: Figure 4.9 Figure 4.10 Figure 4.11

- Page 11 and 12: Executive Summary headspace 1 aims

- Page 13 and 14: Executive Summary or very high leve

- Page 15 and 16: Executive Summary through mental he

- Page 17 and 18: value to society of the improvement

- Page 19 and 20: 1. Introduction people in Australia

- Page 21 and 22: 2. Evaluation Methodology 2.1 Aims

- Page 23 and 24: 2. Evaluation Methodology Evaluatio

- Page 25 and 26: 2. Evaluation Methodology Table 2.3

- Page 27 and 28: 2. Evaluation Methodology Represent

- Page 29 and 30: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 31 and 32: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 33 and 34: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 35 and 36: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 37 and 38: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 39 and 40: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 41 and 42: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 43: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 47 and 48: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 49 and 50: 3. Access and Engagement with Centr

- Page 51 and 52: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Th

- Page 53 and 54: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients 35

- Page 55 and 56: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Ch

- Page 57 and 58: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients No

- Page 59 and 60: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Th

- Page 61 and 62: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Fi

- Page 63 and 64: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients A

- Page 65 and 66: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Ta

- Page 67 and 68: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients nu

- Page 69 and 70: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients No

- Page 71 and 72: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Ta

- Page 73 and 74: y three percentage points, and 2.1

- Page 75 and 76: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients So

- Page 77 and 78: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients I

- Page 79 and 80: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients in

- Page 81 and 82: 4. Outcomes of headspace Clients Wh

- Page 83 and 84: 5. Service Delivery Model For the a

- Page 85 and 86: 5. Service Delivery Model the provi

- Page 87 and 88: 5. Service Delivery Model headspace

- Page 89 and 90: 5. Service Delivery Model services,

- Page 91 and 92: 5. Service Delivery Model services

- Page 93 and 94: 5. Service Delivery Model Further,

3. Access and Engagement with Centres<br />

Table 3.5 Proportion of clients and regional areas who felt that they had waited <strong>to</strong>o long for<br />

an appointment*<br />

YP felt they waited <strong>to</strong>o long for<br />

No Yes missing Total<br />

appointment<br />

major cities 80.7% 7.8% 11.5% 100%<br />

regional areas 78.4% 6.8% 14.8% 100%<br />

* Insufficient data <strong>to</strong> include an analysis of remote centres.<br />

Source: Authors calculations from hCSA data.<br />

As indicated in the Centre Managers Survey, the wait times vary according <strong>to</strong> the practitioner<br />

type, with <strong>young</strong> people waiting longest <strong>to</strong> see occupational therapists, clinical psychologists and<br />

psychiatrists (reported average waiting time in days of 18.4 <strong>to</strong> 19.6), and shorter waiting periods for<br />

vocational workers, youth workers and social workers (reported average waiting time in days of 7.6;<br />

8.6; and 12.4 respectively).<br />

Cultural appropriateness<br />

As indicated above, <strong>headspace</strong> is achieving some success in engaging Indigenous <strong>young</strong> people.<br />

Analysis indicates that a significantly higher proportion of Indigenous <strong>young</strong> people have accessed<br />

<strong>headspace</strong> services than Indigenous <strong>young</strong> people in the general population (7.4% versus 3.7%).<br />

However, interviews with staff in five fieldwork sites confirmed that <strong>headspace</strong> could do more <strong>to</strong><br />

make the service more culturally appropriate for Indigenous clients:<br />

As an organisation I think that we could be better at meeting <strong>young</strong> Aboriginal people and<br />

finding out what they want from us (Youth Worker)<br />

A number of staff who were interviewed raised concerns about staffing, with most being critical of<br />

the fact that their centre did not have an Aboriginal worker. While it was acknowledged that lack of<br />

suitably qualified Aboriginal staff was a sec<strong>to</strong>r-wide problem, it needs <strong>to</strong> be addressed as it was clear<br />

that a number of non-Aboriginal staff found it challenging <strong>to</strong> engage Aboriginal <strong>young</strong> people.<br />

As well as staff shortages, a few workers commented that the centre-based service model did not<br />

meet the needs of Indigenous <strong>young</strong> people: ‘Aboriginal kids don’t usually like coming in<strong>to</strong> an office.’<br />

One staff member further explained:<br />

Of the Indigenous people that I have worked with - just the kind of way that appointments<br />

are set up, attending at a scheduled time, that hasn’t always worked well I don’t think. I think<br />

for that population perhaps it needs <strong>to</strong> be a little more open and flexible on an as needs<br />

basis. So that when things arise there’s somebody there <strong>to</strong> talk <strong>to</strong>, not having <strong>to</strong> book in an<br />

appointment a week later or something like that (Psychologist)<br />

During interviews, staff suggested a number of measures that could improve the engagement of<br />

Aboriginal <strong>young</strong> people. Suggestions included <strong>to</strong>:<br />

• provide training <strong>to</strong> non-Indigenous staff <strong>to</strong> implement culturally appropriate engagement and<br />

treatment practices<br />

• employ more Aboriginal practitioners in centres<br />

• make connections and build relationships with Aboriginal organisations, Aboriginal workers,<br />

and key figures in local Aboriginal communities<br />

• offer different forms of outreach that ‘take the service out <strong>to</strong> them’<br />

• provide more flexible services that do not follow a rigid, place-based, time allocated, clinical<br />

model, but rather are flexible, non-threatening model based on the needs and <strong>lives</strong> of<br />

Aboriginal <strong>young</strong> people.<br />

A third of interviewed staff felt that <strong>headspace</strong> needed <strong>to</strong> improve engagement practices with<br />

Aboriginal <strong>young</strong> people. Most of these staff spoke of the goodwill of centre staff <strong>to</strong> think creatively<br />

and suggest ways <strong>to</strong> better engage local Aboriginal <strong>young</strong> people. However, it was clear that the<br />

pressures of work restricted the enactment of these ideas.<br />

CALD <strong>young</strong> people were found <strong>to</strong> be under-represented in the first evaluation of <strong>headspace</strong> (Muir<br />

Social Policy Research Centre 2015<br />

<strong>headspace</strong> Evaluation Final Report<br />

34