Andries Botha Catalogue

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

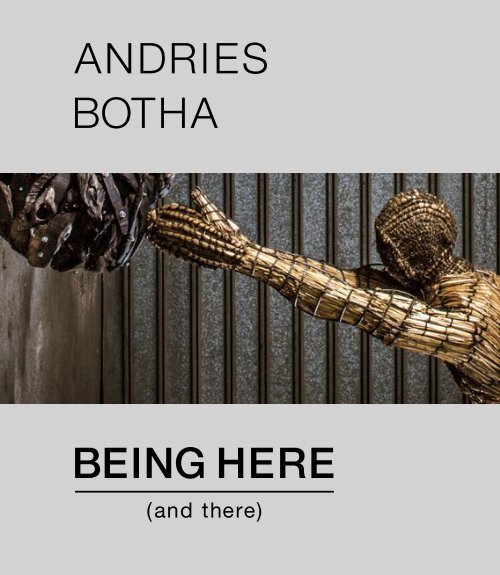

ANDRIES<br />

BOTHA<br />

BEING HERE<br />

(and there)

AN EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY

“Our song is violence, and we sing it beautifully<br />

- I said that? I can’t believe I said that shit.”<br />

- <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong>

CONTENTS<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

Introduction by Trent Read ......................................................................... 1<br />

Being Here (and there) by <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong> ..................................................... 2<br />

Genesis, Genesis, Jesus… ................................................................................ 4<br />

Genesis, Genesis, Jesus… [Detail] ................................................................ 6<br />

Embarkation ..................................................................................................... 8<br />

Embarkation [Detail] ................................................................................... 10<br />

Loxodanta Africana ........................................................................................... 12<br />

Loxodanta Africana [Detail] .......................................................................... 14<br />

Afrikaner Circa 2014 .................................................................................. 16<br />

Afrikaner Circa 2014 [Detail] ....................................................................... 18<br />

Just Being by Hazel Friedman .................................................................... 20<br />

Cirriculum Vitae of <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong> ............................................................... 24<br />

Special Thanks.......................................................................................... 28

INTRODUCTION<br />

BY TRENT READ<br />

Sculpture in South Africa has enjoyed somewhat of a renaissance in the last decade or so, with<br />

arguably the finest and most thought provoking art made in the country being three-dimensional.<br />

This certainly was not the case when I entered the field some forty years ago. The sculptors, on<br />

the whole, were a fairly pedestrian bunch making saccharine bronzes of wildlife subjects, large<br />

monuments to apartheid heroes or, amongst the more up to date, fairly sterile abstracted works<br />

that had a “modern” air to them. We were in the midst of the cultural boycott and although works<br />

by Elisabeth Frink, Lyn Chadwick and a few others were occasionally seen, sculpture was safe,<br />

boring and above all European.<br />

In my opinion two artists were largely responsible for the massive changes that occurred in the<br />

early Eighties long before the ending of apartheid and our reacceptance as part of a larger art<br />

community. The sculptors were Jane Alexander and <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong> and I well remember how<br />

their work made everything else look somehow small and not very interesting. Jane was a<br />

little younger than <strong>Andries</strong> and her output was tiny but <strong>Andries</strong>’ work was inescapable. He made<br />

pieces that were radical in their mix of media and breath taking in their sly subversity (in a<br />

society that was walled in by security laws and where censorship (and worse) were<br />

commonplace). Above all he made works that were African in their choice of subject and use of<br />

media and this was his greatest gift to this country and a huge inspiration to two generations of<br />

students.<br />

I believe this also led to a change of focus by collectors, both private and institutional. Like the<br />

Dutch forefathers of many of them, South Africans tended to collect modest sized paintings<br />

and drawings more appropriate in scale to an Amsterdam townhouse. This started to change in<br />

the early nineties when mixed media sculpture and installations began cautiously to be bought<br />

by a few of the more prescient buyers. This is wholly suited to our landscape and our complex<br />

shared culture.<br />

I think that this show amply illustrates my contention that <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong> is our preeminent<br />

sculptor and I am proud to have been able to facilitate the exhibition at this lovely space at<br />

Grande Provence.<br />

The exhibition is extraordinary in that it is showing a major work from each decade including<br />

one that has only been seen at documenta in Kassel in the 90’s and the works have never been<br />

shown together anywhere.<br />

1

BEING HERE (and there)<br />

BY ANDRIES BOTHA<br />

When I was young and wondering what it would be like not to be what everyone wanted me to be,<br />

unpredictable thoughts became ideas, and then my life. The idea that took shape instantly, in<br />

immediate and unpredictable circumstances, was that I imagined myself as a sculptor, when I did<br />

not even know what sculpture was. I saw a picture of Michelangelo’s slaves lying on my friends<br />

coffee table and asked “...what is this?”. “Sculpture, my mother loves this stuff“, he said. “I am<br />

going to do that “, I said. So that’s the story of my art career; an illogical necessity that keeps<br />

upsetting everyone, but me. Inbetween the what, the how and the why not, hovers a much longer<br />

story, eventually leading me to 2016 and this exhibition with Trent Read.<br />

I was in the familiar space of changing my mind, retreating from the public eye into my own private<br />

space, when Trent showed up at my Durban studio. He saw some of my older work, which I was in<br />

the process of cleaning and restoring, along with some new drawings and offered me a show. The<br />

journey from the private into the public has always been scary. Exposing the intimate as a form of<br />

public intent, subject to market force and critical commentary can become a perilous dance.<br />

I confess I have always been wary of this, shying away from normal commercial gallery leylines.<br />

Most of my major works were made as part of my own meditation on self within the frightening or<br />

challenging South African space. I exhibited (mostly abroad) as part of larger group shows, then<br />

crated and stored the (hidden again) work. Still not sure what all this means but I sort of understand<br />

my life of creativity as a embodiment of this ambivalence or uncertainty. Making sculpture and then<br />

not sure how or where to show it, or if I should at all...,creating the work and making more...<br />

Now I have all this work which speaks of 40 years of sculpture making. And some other stuff, all<br />

neatly stored away. Strange when you look at your life in this way and realise it’s peculiarity...<br />

The works do speak for themselves and have their narratives secretly woven into them. Speaking<br />

or analysing your intent flattens the work and destroys the subtlety and mystery of everything. This<br />

is the viewers work. Upon reflection, I return to similar concerns and merely express them<br />

differently. I soon learnt that material and mode of construction was as important as the ideas that<br />

were being explored. I try to locate the human(ity) within the visceral, social and cultural spectacle.<br />

The complex South African context unashamedly frames the universal human experience. Mine as<br />

well. It is difficult to imagine expressing myself in any other way.<br />

I am going to show 4 major works that frame a history of art making, a sort of love affair in a time<br />

line, if you wish. In addition there will be about 10 large digital prints and 3 multi media Marquette’s,<br />

or three dimensional drawings.<br />

I am pleased to be back in the private contemplative space. Yes, I am hesitant to be journeying into<br />

the public again, but happy I am doing it with Trent. So I come into another circle/cycle.<br />

Interesting how life is...<br />

2

3

4<br />

Genesis, Genesis, Jesus…<br />

leadwood, thatching grass, metal<br />

L 270 x W 123 x H 200 cm<br />

1989

5

6<br />

Genesis, Genesis, Jesus…<br />

[Detail]

7

8

Embarkation<br />

polypropylene rope, wattle wood, galvanized sheeting,<br />

plastic sheeting, canvas, stainless steel mesh, mild steel,<br />

found objects, resin, lead<br />

L 700 x B 350 x H 180 cm<br />

1995<br />

9

10<br />

Embarkation [Detail]

11

12

Loxodanta Africana<br />

polyester resin<br />

L 150 x W 380 x H 105 cm<br />

2011<br />

13

Loxodanta Africana [Detail]<br />

14

15

16

Afrikaner Circa 2014<br />

acrylic on canvas, landscape in the manner of<br />

Pierneef; material one; mild steel; 3D printed<br />

figure in supawood; artificial landscape turf<br />

Variable dimensions<br />

2014<br />

17

18<br />

Afrikaner Circa 2014 [Detail]

19

JUST BEING<br />

BY HAZEL FRIEDMAN<br />

‘The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very<br />

existence is an act of rebellion’. - Albert Camus ‘The Stranger’ (1942)<br />

There’s a scene in the movie ‘Being There’ where USA President ‘Bobby’ asks Chauncey<br />

Gardner (Chance the Gardener) his prognosis for economic growth. ‘As long as the roots are not severed,<br />

all will be well in the garden’, is the reply by a presidential candidate whose mind has been engineered to<br />

respond in simplistic homilies snugly blanketed in bucolic adjectives.<br />

You might ask what a movie about a simple, sheltered gardener who becomes an insider in Washington<br />

politics has to do with an artist whose profundity of vision represents the very antithesis of shallow<br />

sound-bites and abbreviated attention-spans?<br />

Yet ‘Being Here (and there)’, the title of <strong>Andries</strong> <strong>Botha</strong>’s first exhibition on South African soil in many years<br />

does remind me of the universal wisdom of simplicity, of being in the moment and of revisiting roots that<br />

might have been dug up, replanted, rerouted but never fully severed. ‘Being There (or there)’ is about the<br />

parody and deconstruction of engineered personal and public narratives.<br />

<strong>Botha</strong>’s work is paradoxically ‘rooted’ in a sense of dislocation and non-belonging. In his artists’<br />

statement for ‘Being Here (or there)’ he describes producing most of his major works ‘as part of my own<br />

meditation on self within the frightening, or challenging South African space’. He also speaks openly about<br />

the ambivalence he feels between embracing the international success of his career and an essentially<br />

solitary creative quest: withdrawal from the public pantheon in order to nurture ‘an internal space’. Both<br />

activist and archivist, <strong>Botha</strong> has produced sculptural installations that stand tall among the greatest<br />

contemporary South African public art produced during and after apartheid. This public art has evolved<br />

from a profoundly personal, ongoing struggle that has served as a recurring refrain in his life and art.<br />

Although located in the specifics of time and place, it transcends both states, becoming ‘a part of’ yet<br />

remaining ‘apart from’.<br />

There is a harmonius ebb and flow to the artist’s conversation. Eloquent and elegant, his sentences are<br />

layered, intricately structured and interwoven with metaphor and meaning, much like the monumental<br />

sculptural installations that mark four decades of a stellar career, replete with prestigious individual artistic<br />

awards, major public commissions, ongoing community projects and international showings; not to<br />

mention political controversy. But underpinning <strong>Botha</strong>’s prodigious oeuvre is a disarming simplicity and<br />

almost self-deprecatory humility. Despite his global success, he has remained surprisingly free of the<br />

hustle and hype that often sticks to the coattails of celebrity, like dust on velcro.<br />

For ‘Being Here (or there)’, gallerist and exhibition curator, Trent Read has selected four major installations<br />

that serve as indeces to the four decades of his extraordinary output. <strong>Botha</strong> describes his collaboration<br />

with Read as an ‘incredible synergy’. The works have never been seen together, and one of them has only<br />

ever been seen at Documenta in Kassel in the 90’s. They include ‘Genesis, Genesis Jesus’ (1989),<br />

‘Embarkation’ (1995), ‘Afrikaner Circa 2014’ and ‘Loxodonta Africana’ (2015). Also included in this seminal<br />

show are 10 large digital prints and 4 multi media drawings, mapping some of the dominant terrain<br />

traversed by <strong>Botha</strong> over the last four decades.<br />

20

Revisiting these fruits of a labour-intensive career located in the literal materiality of the South African<br />

landscape must constitute an exhilarating rediscovery for <strong>Botha</strong>. From the prism of time and distance they<br />

offer fresh insights and revelations, while re-affirming the artist’s ongoing themes. “I have always<br />

interrogated public space around presence and absence of monumentality,” he explains, ‘and how we go<br />

about rewriting an engineered narrative. “In many respects these works represent a continuum of recurring<br />

concerns, merely expressed differently”.<br />

<strong>Botha</strong> cautions against over-analysis of artistic intention. The work must speak on multiple layers, both<br />

patent and subliminal, intellectually and intuitively. The multivalent layers of his art that they speak, not only<br />

to, but also about the past four decades. They continue to resonate in a world that has become<br />

increasingly atomised, fractured and digitally arcane. It is impossible to adequately encapsulate the breadth<br />

and depth of <strong>Botha</strong>’s creative journey in a single essay. To describe his personal quest as a search for<br />

authenticity and identity through the thicket of ideological fictions goes some of the way towards attaining a<br />

neat, albeit simplistic, definition. But even though the struggles with the contradictions of his own heritage<br />

– raised as a white Afrikaans male during apartheid – form the most obvious bookends of his works. <strong>Botha</strong>’s<br />

creative trajectory is far more subtle and fluid.<br />

He recalls being shaken out of his prescribed ‘Afrikaner identity’ by the discourse of young black activists,<br />

and being awoken to the imperatives of interrogating an ‘engineered’ narrative not merely around the<br />

justifications for political disenfranchisement but about ‘the destruction of humanity itself’. Although tutored<br />

in the ‘mimicry of a Eurocentric modernity’ <strong>Botha</strong> also began to rebel against the art-from-the-west-is-best<br />

mindset, with its emphasis on a ‘fine-art’ hierarchy and gallery system. Apartheid ethnocentrism had<br />

undermined the aesthetic value of indigenous South African cultural production and artifacts. During the<br />

political upheavals of the mid 1980s, the ideological glue that had bound this form of cultural snobbery was<br />

starting to come unstuck. It was principally artists like <strong>Botha</strong>, who wholeheartedly embraced the traditional<br />

weaving techniques and materials from the midlands of KwaZulu-Natal, where he was raised, that South<br />

African traditions of craft-art, who practiced predominantly in rural areas, became legitimised – albeit<br />

belatedly - by the mainstream South African art world.<br />

Disruptive and distorted power relations between Eurocentric and African paradigms are dramatically<br />

articulated in Genesis, Genesis Jesus (1989), which can be read as much in terms of spiritual conflict as<br />

it does about the interface between material, mythology and metaphysics. A prostrate, Promethean-type<br />

form is stacked and packed from leadwood - a protected deciduous South African tree. It provides a plinth<br />

for the acrobat/dancer possessed of the grace of a Degas or Rodin sculpture. Yet this form is constructed<br />

not from the ‘classical’ materials of the European sculptor, but rather from the craft-intensive traditional<br />

Zulu grass weaving techniques. In this work brute force and beauty coalesce in a precarious pas de deux.<br />

Both material and metaphor make powerful references to bodies, land and the historical contestation<br />

thereof – a conflict that continues well into the 22nd year of post-apartheid South Africa and feeding into<br />

current debates around transformation and other combustible discourses.<br />

Executed at the cusp of a new era in South African history it is impossible to avoid a political reading of<br />

<strong>Botha</strong>’s work during the late 1980s and early- mid 1990s. But this becomes a rather glib observation in<br />

relation works like ‘Embarkation’ (1995) – one of <strong>Botha</strong>’s works that while emblematic of an era, defies neat<br />

21

categorisation. As the artist explains on his website ‘Embarkation’ is ‘a sculptural fragment‘ of a 6-piece<br />

installation entitled What is a Home. Using symbolicall ycharged materials, such as wood from ’alien’ trees,<br />

galvanised zinc and plastic sheeting – referencing the materials of informal settlements - canvas, tyres,<br />

telephone wire and found objects, the work is much more than a meshing of Western and African culture.<br />

It explores the trajectory of identity and diaspora, both in the contexts of personal memory, politics and<br />

cultural currency. Indeed, the bipolar states of local versus international have complicated the production,<br />

display and consumption of art, particularly of a democracy that, at 22 years-old, is still, relatively, the<br />

ingénue at the global art ball. ‘Embarkation’ is about the perennial outsider. The converse is also suggested<br />

through the narrow spaces between <strong>Botha</strong>’s physical forms and the physical topography they evoke; that<br />

there is often an inextricable sense of ‘belonging’ between self and land. It is a bond that has been used<br />

to justify the most violent contestations of ownership. Yet ‘Embarkation’ ultimately denotes a state of<br />

departure, arrival and transit. It also suggests that art, like self-identity and cultural identification, is always<br />

on a threshold, shifting from stasis to passage, and vice versa.<br />

‘Afrikaner Circa 2014’ is the third of the four installations that as <strong>Botha</strong> explains ‘frame a history of<br />

making, a sort of love affair in a time line’. In this work, as with the others there is an intricate interweaving<br />

of social, spiritual, cultural and historical representations. It is also in this work that one can<br />

choose to focus on <strong>Botha</strong>’s documentary and conceptual strategies that are informed as much by language<br />

and political theory as by aesthetic discourse. The date that marks the genesis of the ANC -1912 - is also<br />

the date that a new breed of cattle came to the attention of South African farmers: the Afrikaner. Although<br />

it had been around for about 2000 years and was widely used by the ‘Hottentots’ in the era of Jan Van<br />

Riebeeck, this breed, like the Volk after who it has been named, was nearly exterminated in the Boer War.<br />

The Afrikaner cattle – that ‘pure bred’, yet inbred, prized, hybridized beast that has now been located or<br />

dated as ‘circa’ - as a ‘historical’ – possibly extinct - phenomenon, identified principally by an indeterminate<br />

date of origin, much like a fossil or fragment of bone excavated from an archaeological site. Perched<br />

in the background of the installation is a framed landscape by Pierneef, appropriated by <strong>Botha</strong> to critique<br />

the fiction of South African nationalism that represented the landscape as an unpopulated paradise to be<br />

conquered and civilised by whites. In these works <strong>Botha</strong>’s parody and subversion of language is integral to<br />

the narrative of the work. The Afrikaner metaphor also alludes to masculinity, hides, skins and, of course, in<br />

traditional husbandry and African culture, to currency and wealth. It is as though the material has memory,<br />

like muscle. As such, the work is as much about the mediation of human agency in the valuation of objects<br />

within a matrix of socio-political structures as it is about the flux of histories, cultures and identities.<br />

There is however also a profoundly intimate subtext to ‘Afrikaner Circa 2014’ that relates directly to an<br />

earlier work executed in 2006 called ‘Afrikaander Circa 1600.’ As <strong>Botha</strong> himself explains of the former<br />

installation: “In many respects, it signifies the closure of a ‘tender conversation’ between myself and my<br />

father that was first articulated in ‘Afrikaander circa 1600’.” This conversation between father and son<br />

revolved around the ongoing, painful struggle <strong>Botha</strong> has expressed about the Dutch-Afrikaner identity - the<br />

distorted colonial embodiment of masculinity and patriarchy - imposed upon him and generations of South<br />

Africans. Both installations are comprised of materials and archetypal imagery associated with domesticity,<br />

agriculture, anthropology and archaeology. Each exudes a sense of containment – the focus of the earlier<br />

work is literally a container - while in ‘Afrikaner circa 2014’ the Ram is caged in a coop whose diameters<br />

conform to the classical measurements used to cordon off archaeological sites.<br />

The excavation metaphor is redolent with association, alluding to digging up or unearthing hidden<br />

histories and exposing which ‘lies’ are buried beneath the surface. It speaks of fracture, erasure and<br />

22

historical trauma that are as much of the individual psyche as they are the consequence of collective,<br />

cultural misrepresentations.<br />

At the risk of providing an overly manicured trajectory of <strong>Botha</strong>’s 40-year oeuvre it is evident that one of his<br />

increasingly visible and volatile concerns revolve around using art as a means of challenging and exploring<br />

alternate models of survival in shifting, interdependent environments.<br />

“I’ve been creating metaphors that frame human experience in the landscape, so it was inevitable that my<br />

art would embrace the ecological meta-narrative that informs and will determine the survival of our planet”,<br />

he explains of his many collaborative sculptures and themes revolving around conservation. Fittingly, the<br />

fourth major work in ‘Being Here (or there)’ is ‘Loxodonta Africana’ (2015). Translated from Latin as<br />

Savannah Elephant, it represents an archetypal symbol of power; its Zulu name is Ndlovu, meaning ‘chief’.<br />

It also symbolises collective unconscious and the unspoken conversation between humanity and the<br />

natural ewwecology. This symbol has also been crudely appropriated by power-mongers and king-makers<br />

to engineer their own narratives of political hegemony. In <strong>Botha</strong>’s lexicon it patently and poignantly references<br />

Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna’s depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian - the 15th century<br />

saint, known as the ‘protector of plagues. His death unleashed a devastating epidemic that almost<br />

decimated Europe. <strong>Botha</strong>’s analogy is chilling. The wounded elephant is emblematic of an endangered<br />

planet’ – a state of being that, as <strong>Botha</strong>’s friend and mentor, the late Ian Player warned, was entering into<br />

the collective sub-conscious.<br />

‘We are at the point in our history where the very best of our reason has placed us at the greatest risk of<br />

destroying ourselves and our habitat’. He warns: ‘This is the time to explore different modalities that<br />

mediate the dance between head and heart.’<br />

The real powers that shape the conditions under which we all act these days flow in global space. They<br />

determine the commercial traffic between conservation and culture; not to mention their co-option.<br />

At the time of conceptualizing this essay, South Africa again encapsulates the contradictions that beset<br />

the planet in the terrain of ecology, education, economics, heritage, ideology and psychology. Bodies, land<br />

and power still remain contested terrains of transformation. Small men with oversized egos preen on public<br />

podiums, intent on re-engineering new artifacts and fictions of power; the roots thereof are often banal but<br />

their implementation brutal and narcissistic. We have attended the self-congratulatory conferences; we<br />

have read the noble legislation, gaping at the abyss between intention and implementation. And we have<br />

watched the mind-numbing reruns of the miniseries with their revolving door of characters. Like the people<br />

populating the inchoate world of Chauncey Gardner in ‘Being There’, the script and sound-bites, like the<br />

collective attention-span, simply get shallower.<br />

23

CURRICULUM VITAE<br />

OF ANDRIES BOTHA<br />

Exhibitions<br />

2015<br />

2014<br />

2012<br />

2011<br />

2010<br />

2009<br />

2008<br />

Donated the permanent exhibition of a life size elephant sculpture to the<br />

Shobiyana Secondary School as part of a creative project: “Skills of Our<br />

Children”, Acornhoek, Mpumalanga, South Africa.<br />

Participated in Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency, Florida, USA.<br />

“100”, Centenary Exhibition, Everard Read Gallery, South Africa,<br />

14 November 2013-31.<br />

January 2014. Artwork: “Afrikaner circa 2014”, Acrylic on canvas, landscap in<br />

the manner of Pierneef; Material One; mild steel; 3D printed figure in<br />

Supawood; artificial landscape turf.<br />

Museum Beelden aan Zee, Den Haag, Netherlands, “The Rainbow Nation”, from<br />

29 May to 9 September 2012 on the Lange Voorhout and from 8 June to<br />

30 September 2012 in Beelden aan Zee Museum.<br />

Circa on Jellicoe, Rosebank, Johannesburg, South Africa, one-man exhibition,<br />

“(IN)SOMNIUM)”.<br />

Group Exhibition: “The Horse”, Everard Read Gallery, Johannesburg “2011<br />

Incheon Women Artists’ Biennale” – South Korea, Amazwi Abesi<br />

fazane project.<br />

Woordfees Artist, One man exhibition, Stellenbosch, South Africa.<br />

North American tour of Nomkhubulwane (elephant sculpture) including Chicago,<br />

Fayetteville, Bozeman, El Paso, Detroit – USA and Juarez and<br />

Cuernavaca in Mexico.<br />

La Papalote Museum, Mexico City, Mexico.<br />

Wild9 – 9th World Wilderness Congress, Merida, Mexico.<br />

Animal-Anima, Provence, France.<br />

South Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa.<br />

KZNSA Gallery, Durban South Africa.<br />

Strydom Gallery, George, South Africa.<br />

Beauty and Pleasure, Stenersen Museum, Oslo, Norway.<br />

Faculty Exhibition, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa.<br />

Workshop/Exhibition, Samata Lok Santhan, Gwalior, India.<br />

Travesia, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.<br />

l’Homme est un Mystère #3, St. Brieuc, Côtes d’Armor, France.<br />

24

2007/9<br />

2007<br />

2006<br />

2005<br />

2004<br />

2003<br />

2002<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

You can buy my heart and my soul, Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren,<br />

Belgium, October 2007 to June 2009.<br />

You can buy my heart and my soul, Antwerp, Belgium.<br />

2006 Beaufort, Sculpture Triennale, De Panne and Ostend, Belgium<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, William Benton Gallery, University of Connecticut, USA<br />

Africa Remix, Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf, Germany<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Betty Rymer Gallery, School of the Art<br />

Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Culturgest, Lisbon, Portugal<br />

Attese: Biennale of Ceramics in Contemporary Art, Albisola, Italy<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Africa Studie Sentrum, Leiden, The Netherlands<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Imagine IC, Amsterdam, The Netherlands<br />

Vidarte 2002, Mexico City, Mexico<br />

Global Priorities, New York, USA<br />

Outpost II, US Art Gallery, Stellenbosch, South Africa<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Prince Claus Fund, The Hague, The Netherlands,<br />

Freehouse Project, Rotterdam, Netherlands<br />

Nature, Utopia and Realities: Orsorio, Grand Canarias<br />

Memorias: Santander, Spain<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, World Conference Against Racism, South Africa<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane, Durban Art Gallery, South Africa<br />

Area 2000: Reykjavik Art Museum, Iceland<br />

L’Afrique a Jour: Lille, France<br />

Bonnefanten Museum, Maastricht, Holland<br />

Dakart 2000 Biennale, Senegal, Africa<br />

Amazwi Abesifazane – Voices of Women, African Art Center, South Africa<br />

Galerie Paul <strong>Andries</strong>se, Amsterdam<br />

25

1998<br />

1997<br />

1996<br />

1995<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

Kasselkunstverrein: Kassel, Germany<br />

Kulturtogbet Solvberget,Stavanger, Norway<br />

Four Seasons – National Architectural Institute, Rotterdam<br />

Johannesburg Biennale, South Africa<br />

Samtidskunst: Fra Sor Afrika, Oslo, Norway<br />

The Other Journey: Africa and the Diaspora, Kunsthalle Krems, Vienna<br />

Containers Across the Ocean, Copenhagen<br />

Cris Fertiles Unesco, Abidjan<br />

Cris Fertiles Unesco, Cotonou<br />

Transitions: Bath Festival – United Kingdom<br />

South African Contemporary Art, Paris, France<br />

Southern Cross – Stedelijke Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands<br />

Venice Biennale, Italy<br />

Honours<br />

2003/4<br />

2000<br />

1998<br />

1994<br />

1992<br />

Consultant to the Department of Arts of Culture, Nkosi Luthuli Memorial,<br />

Kwa-Dukuza.<br />

Playground and Toys, United Nations, New York<br />

One of 12 International artists invited by Holland Foundation to work on Ujama iv<br />

project in Maputo, Mozambique<br />

Civitella Raneiri Fellowship, Italy<br />

U.S. Information Service Fellowship – University of Indiana, USA National Vita<br />

Art Award, South Africa<br />

Public Commissions<br />

2015<br />

2013/16<br />

2011<br />

Completed Three (Four) elephant sculptural installation, City of Durban,<br />

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.<br />

State Commission for six 2m tall bronze figures.<br />

Sculptural installation of Rev John Dube for Dube Tradeport in Durban,<br />

South Africa<br />

26

2009<br />

2008<br />

2006<br />

2004/6<br />

2004/9<br />

2003<br />

2001<br />

2000<br />

1999<br />

1997<br />

1996<br />

1993<br />

1992<br />

Started the halted Three Elephant sculptural installation, City of Durban,<br />

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa<br />

King Shaka Sculptural Installation, King Shaka Airport, Durban,<br />

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.<br />

“Lux Themba”, Family Memorial, Amsterdam, Netherlands<br />

Award design and manufacture: 27th Durban International Film Festival.<br />

Ohlange Memorial Park – ANC Memorial, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal,<br />

South Africa – 5 larger-than-life bronze figures.<br />

Gandhi Foundation Awards.<br />

Shembe Memorial, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.<br />

Sculpture Commission, Vodacom, Cape Town, South Africa.<br />

Rijksakedemie Voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Holland.<br />

Sculpture Commission, M.T.N., Johannesburg, South Africa.<br />

Sculpture Commission, Hilton Hotel, Durban, South Africa.<br />

Sculpture Commission, Durban Girl’s College, South Africa.<br />

Sculpture Commission, Standard Bank, Johannesburg, South Africa.<br />

Sculpture Commission, Johannesburg Art Gallery, South Africa.<br />

Teaching Experience<br />

1982 -<br />

2014<br />

Senior Lecturer, Sculpture, Durban University of Technology, Durban,<br />

South Africa.<br />

27

SPECIAL THANKS<br />

We wish to acknowledge the following individuals’ contributions to this catalogue:<br />

Karla Benade,<br />

Zandré October,<br />

Jessica Botness,<br />

Janine Zagel,<br />

Theresa Kaati,<br />

Philip Heijnen,<br />

Wentzel Combrinck.<br />

Photography by Sean Laurenz.<br />

28

gallery@grandeprovence.co.za<br />

www.finearts.co.za<br />

Main Road, Franschhoek<br />

PO Box 102, Franschhoek 7690<br />

Western Cape, South Africa<br />

T +27 (0)21 876 8630