Edward Lee

Edward Lee Book

Edward Lee Book

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong><br />

Model Employer and<br />

Man of Moral Courage<br />

By MICHAEL LEE<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

1

2

<strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong><br />

Model Employer and<br />

Man of Moral Courage<br />

By MICHAEL LEE

The earliest known photograph of <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie <strong>Lee</strong> taken 6 September 1886.

<strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong><br />

Model Employer and<br />

Man of Moral Courage<br />

By MICHAEL LEE

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

© Michael <strong>Lee</strong> 2016<br />

mikelee2653@gmail.com<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be<br />

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrievable system,<br />

or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic,<br />

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without<br />

the prior permission of the<br />

copyright holder.<br />

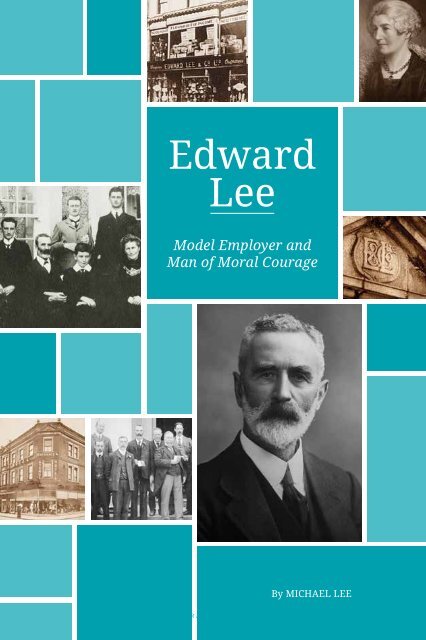

Cover photographs.<br />

Top.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s first shop at No 2, Goldsmith Terrace, Bray.<br />

Annie <strong>Lee</strong> in the 1920s.<br />

Middle.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie with their four sons (circa 1906).<br />

Granite pediment, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> & Co. Ltd, Dún Laoghaire.<br />

Bottom.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> & Co. Ltd, Dún Laoghaire (circa 1940s).<br />

Bray Urban District Council 1906.<br />

Portrait photograph of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> ( circa early 1920s).<br />

All photographs <strong>Lee</strong> archive.<br />

ISBN 978-0-9956091-0-5<br />

Produced by Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council<br />

Designed, printed and bound by Concept2Print

Contents<br />

Foreword by Pádraig Yeates 6<br />

Preface 8<br />

Acknowledgements 10<br />

Tyrrellspass, Co. Westmeath 12<br />

John Wesley 13<br />

Tyrrellspass 1853 14<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> & Co. 1885 16<br />

Social Conscience 19<br />

The Grange 23<br />

America and Canada 1904 26<br />

Benefactor 34<br />

1913 Lockout 35<br />

Sir Hugh Lane 42<br />

Bellevue and Home Rule 44<br />

The Great War 1914-1918 46<br />

Town Tenants League 50<br />

The Sinking of the RMS Leinster 51<br />

A Place in the Sun 53<br />

1920s and 30s 55<br />

An Honest Christian Man 60<br />

Appendix: Memoranda of a Hurried Visit to America and Canada 1904 63

Foreword<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was a Protestant, a Unionist and a Freemason, someone who<br />

would automatically have been dismissed as a stereotypical pillar of the<br />

British establishment in Ireland until recently. But one of the benefits of<br />

the current ‘Decade of Centenaries’ has been a greater public willingness<br />

to engage with and understand people and events from our past. I am not<br />

talking about the ‘shared’ history, or meaningless ‘inclusivity’ that mars<br />

many official commemorations, but a willingness to look at our historical<br />

legacy from fresh and better informed perspectives. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> is an<br />

important Dublin figure from the early twentieth century, deserving of<br />

reappraisal and this excellent biography by his great-grandson Michael<br />

<strong>Lee</strong> amply will repay the reader’s curiosity with interest.<br />

Reading it, one of the phrases that jumped off the page for me, was <strong>Lee</strong>’s<br />

belief in, ‘A good day’s pay for a good day’s work’. It did so because one<br />

of his contemporaries, Jim Larkin, the founder of modern Irish trade<br />

unionism had a similar saying; ‘A fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work’.<br />

Regrettably, it is also one of Larkin’s least cited quotes. But this shared<br />

belief helps explain why it was possible for one of Dublin’s leading<br />

employers to break ranks with his class and make repeated attempts to<br />

end the Dublin Lockout of 1913. It was proof that even at the height of<br />

Ireland’s bitterest industrial dispute, when the employers’ leader William<br />

Martin Murphy was determined to smash Larkin’s infant Irish Transport<br />

and General Workers Union, there were capitalists willing to compromise<br />

with labour’s militant new leaders.<br />

As the author points out, <strong>Lee</strong> was a deeply moral individual who believed<br />

he had responsibilities to the society in which he lived, regardless of its<br />

political complexion. This belief was central to everything he did, even<br />

while ‘fumbling in the greasy till’ to make a few bob. He introduced a<br />

weekly half-day off for staff a quarter of a century before it was made<br />

mandatory by the 1912 Shops Act and, as Chairman of Bray Urban District<br />

Council, he presided over an ambitious public housing programme for<br />

poorer residents. He continued this policy by subsequently providing<br />

8<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

accommodation for his own employees in Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). It<br />

was this belief in fairness that enabled people such as <strong>Lee</strong> and Larkin to<br />

become champions in their different ways of social progress. Of course<br />

other employers, including Murphy, considered themselves moral men<br />

too, but it was a public morality worn as a carapace to impress the<br />

world, within which they devoured their enemies, including ‘disloyal’<br />

employees. A problem <strong>Lee</strong> never appears to have experienced.<br />

He began life as a Liberal Unionist, yet always regarded himself as an Irish<br />

patriot, like many of his 92,000 co-religionists in Dublin city and county.<br />

This deeply held pride in all things Irish led him to join with Murphy<br />

and other business leaders in organising the International Exhibition<br />

of 1907 to showcase Irish industry. He saw the development of new<br />

enterprises as the only antidote to emigration which, in his own words,<br />

was ‘slowly bleeding the country white’. It also saw his views evolve<br />

towards accepting the concept of Home Rule and then the establishment<br />

of the Irish Free State. On the way, he saw three of his four sons serve in<br />

the British army during the Great War. Two did not come back and the<br />

third only did so after being seriously wounded. It is hard for us today<br />

to conceive of the legacy of suffering that conflict inflicted, not alone in<br />

Ireland but across Europe. It would blight the lives of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and his<br />

wife Annie until their deaths. This book throws fresh light on their lives<br />

and their world that deserves a wide readership from all those interested<br />

in our past, present and future.<br />

Pádraig Yeates<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage 9

Preface<br />

Except for a few family stories, some correct and some which proved<br />

to be inaccurate or simply untrue, my brother <strong>Edward</strong> and I knew very<br />

little about our great-grandfather <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and his life and times. The<br />

story was simply never mentioned in the family. I really believe that our<br />

own father, <strong>Edward</strong> knew practically nothing about his grandfather.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s other grandsons, John and David, also seemed to know<br />

little. Perhaps at the time it was all too painful, especially for the two<br />

surviving sons, <strong>Edward</strong> (Ted) and Tennyson, to talk about the old family<br />

because that would inevitably mean talking about their two brothers, Joe<br />

and Robert Ernest, both of whom had been killed in the Great War. Their<br />

loss was an enormous tragedy for the family and something from which<br />

they never really recovered.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie <strong>Lee</strong> had created a successful drapery business out of<br />

nothing but hard work and a will to succeed. The family and the business<br />

shone brightly for an amazing but brief time, a time that encompassed<br />

enormous upheavals in society both at home and on the world stage.<br />

During all that period, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> had a vision of his ideal of what both<br />

society and business should be. Although it was perhaps both quixotic<br />

and utopian, it was a wonderful ideal. However, it was <strong>Edward</strong>’s family<br />

that took centre stage throughout his life When the two boys died in the<br />

Great War, something in the old couple died too. You can see it in the later<br />

photographs of <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie, the light in their eyes slowly dimming.<br />

After their deaths in 1927 and 1938 respectively, the business carried on<br />

through the decades up to its eventual demise in the late 1970s when the<br />

light flickered one last time and finally died too.<br />

My older brother <strong>Edward</strong> took on a huge amount of the research and is<br />

tenacious in his endeavours to find out more. I, on the other hand, have<br />

a particular interest in the Great War and the story of the two ‘lost boys’,<br />

Joe and Robert Ernest. Their loss was a devastating blow for <strong>Edward</strong><br />

and Annie and, I believe, fundamental to an understanding of their<br />

subsequent lives. Now, with the benefit of modern research methods, we<br />

10<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

are gradually piecing the family story together. However, as with most<br />

research, the more we find out, the more there is left to discover. Then<br />

there are those haunting, faded family photographs, all taken with the<br />

light of the sun over one hundred years ago. They are so tantalising -<br />

shadows long disappeared - each face looks directly at us, eye to eye,<br />

willing us to know their names. You can almost hear them shouting out<br />

from the depths of the past. Even with the best of modern technology,<br />

it is simply not possible to identify more than a handful of family and<br />

friends. We know they are there, we can almost talk to them, but who<br />

are they? It is most likely that at this remove, we will never know. And<br />

finally, there are those beautiful and moving family letters that <strong>Edward</strong><br />

sent to his youngest son Tennyson during the Great War. Full of sadness,<br />

affection and hope, but most of all – love.<br />

Michael <strong>Lee</strong>, September 2016<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage 11

Acknowledgements<br />

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, in particular Marian Keyes,<br />

Senior Executive Librarian, dlr LexIcon. Marian suggested the idea of an<br />

exhibition on my great-grandfather <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>, for dlr LexIcon. He would<br />

have very much approved of this jewel of knowledge in Dún Laoghaire.<br />

The library’s emphasis on education and learning for all, would have<br />

struck a chord with the ‘governor.’ It has been a great pleasure to have<br />

worked with Marian on the project. She has been a good friend and the<br />

guiding force to see it through.<br />

Terry de Valera. (A Memoir. Currach Press, 2004). Some years ago I was<br />

fortunate to meet and talk with the late Terry de Valera and he was most<br />

generous with his memories of his mother Sinéad de Valera and Annie<br />

<strong>Lee</strong> at Bellevue.<br />

Philip Lecane. (Torpedoed! The RMS Leinster Disaster. Periscope<br />

Publishing, 2005). A best ‘pal’ and the man who knows more about the<br />

Leinster tragedy than anyone. Philip was kind enough to read my early<br />

manuscript and gave me great advice which improved it no end.<br />

Stephen McCormac, Archivist, Royal Hospital, Donnybrook. With grateful<br />

thanks to Stephen, who was kind enough to trawl through the RHD<br />

archives. He filled in some missing pieces on Robert Ernest <strong>Lee</strong>.<br />

Tadhg Moloney. Another ‘pal’. Thanks Tadhg for the information on<br />

Captain Robert Ernest <strong>Lee</strong>, Royal Army Medical Corps at Hill 60, Ypres<br />

in 1915.<br />

Philip Orr. (Field of Bones. An Irish Division in Gallipoli. Lilliput Press,<br />

2006). Historian and friend. Thanks Philip for Rev. Robert Spence’s<br />

poignant description of finding Joe <strong>Lee</strong>’s remains.<br />

Pádraig Yeates. (Lockout Dublin 1913. Gill and Macmillan, 2000, 2013).<br />

Enormous thanks to my friend Pádraig, author of quite simply the best<br />

12<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

ook by far on the 1913 Dublin Lockout and the man who originally put<br />

me onto my great-grandfather’s story. For this, the <strong>Lee</strong> family are most<br />

grateful.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>, my big brother and Ursula <strong>Lee</strong>, our late mother, who had the<br />

foresight to understand the importance of the family history, saved the<br />

photographs and most importantly, told us the stories. The late John <strong>Lee</strong>,<br />

who generously gave me the precious letters of his grandfather, knowing<br />

that this was a story worth telling and Ishbel <strong>Lee</strong>, who understands what<br />

I have tried to do. David <strong>Lee</strong>, who has been most helpful and Sally Dunne<br />

<strong>Lee</strong> for her support.<br />

Richard Howlett and the team at Concept2Print including Eliane Pearce<br />

and Olivia Hearne for their great design skills.<br />

Thanks also to, Karen D’Alton, Alyson Gavin, Patrick H. Lynch, Niall<br />

Martin, Peter Pearson, Michael Pegum, Eugene Ryan, Colin and Anna<br />

Scudds, Tim Carey and Nigel Curtin. With gratitude to Aaron Binchy,<br />

Librarian, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Glenn Dunne, National<br />

Library of Ireland and Pearl Quinn, Stills Librarian, RTÉ.<br />

This book is dedicated to: Margaret, <strong>Edward</strong> E, Susan, Pamela, Thomas,<br />

Jennifer, Christopher, <strong>Edward</strong> F., Nicholas, Stephen, Cameron, Jordan,<br />

Freya, Isabella-Rose and <strong>Edward</strong> Samuel. In memory of Andrew<br />

Frederick, <strong>Edward</strong> (Dad) and Ann.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage 13

Tyrrellspass, Co. Westmeath<br />

The village of Tyrrellspass lies in the south of Co.Westmeath,<br />

on the main Dublin to Galway road. It takes its name from the<br />

Tyrrells, who arrived with the Normans in the 12th Century.<br />

The family were originally from Tirel, now called Triel on the north<br />

bank of the Seine, not far from Paris. Hugh Tirel was one of the Norman<br />

soldiers who arrived with Strongbow in 1169. The name Tirel eventually<br />

became Tyrrell. After dispossessing the O’Dooley clan of their lands,<br />

the Tyrrells took possession of the Barony of Fertullagh. Over the next<br />

four hundred years, the Tyrrells consolidated their hold on the whole<br />

area by building fortified castles. The most important was Tyrrellspass<br />

Castle, built around 1410, at the narrow south-westerly end of the village.<br />

Tyrrellspass is situated in the middle of a bog. At the time, the whole<br />

area was virtually a swamp. Travel was difficult and perilous and the<br />

village was the only place of refuge for travellers. The ‘pass’ part of its<br />

name comes from the fact that throughout the centuries, the village was<br />

defended by the Tyrrells. Richard Tyrrell, a descendant of Hugh, was the<br />

victor of the Battle of Tyrrellspass in 1597. This battle, against the forces<br />

of Lord Mountjoy, the Lord Lieutenant, took place at Ballybohan, north<br />

of the village and was a complete victory for the Tyrrell forces. However<br />

with the coming of Cromwell to Ireland, the Tyrrell strongholds were<br />

destroyed in 1649.<br />

The next family to influence the lives of the inhabitants of Tyrrellspass<br />

were the Rochforts. They were a wealthy and powerful family of French<br />

origin, who originally settled in Ireland in 1243. The Westmeath branch<br />

of the family was descended from Prime Iron Rochfort, a Lieutenant-<br />

Colonel in Cromwell’s army. His grandson, Robert, became the first Earl<br />

of Belvedere and much of the town of Tyrrellspass and surrounding area<br />

came into the possession of the Rochforts. The last Earl of Belvedere<br />

married the daughter of James McKay, a Protestant clergyman in 1803.<br />

14<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

Jane, who would become Countess of Belvedere, was born in 1775.<br />

When the Earl died in 1814, Jane hired a King’s council, Arthur Boyd, to<br />

establish her title to the estate. This he did and he also won Jane herself.<br />

They married in 1816 and named their son George Augustus Boyd. The<br />

present village was laid out by the Countess. A village green was created<br />

where originally there had only been a swamp. The beautiful crescent<br />

of Georgian houses was also constructed, as was the courthouse, the<br />

Protestant school and the Methodist chapel. The Countess was known as<br />

a kind and caring landlord, noted for looking after the welfare of her<br />

tenants. When she died in 1836, she left a vastly superior village which is<br />

the Tyrrellspass we know today. In 1846, the Rochfort name was added<br />

and the family were known as Boyd-Rochfort.<br />

John Wesley<br />

John Wesley and his younger brother Charles founded Methodism<br />

during the second half of the 18th Century. Originally it was a<br />

movement within the Church of England, where men and women<br />

met to study the Bible, pray together and encourage each other in<br />

their faith. Essentially a working class movement, Methodism appealed<br />

to people who felt they didn’t have the fine manners or clothes to go to<br />

regular church services. Because of this, Methodist preachers realised<br />

that they needed to go out to the ordinary people. This was known as<br />

‘field preaching’, where the preacher would set up in village greens or<br />

market places or anywhere he could attract an audience. Many poor Irish<br />

peasants, listening to their words of salvation, responded positively to<br />

the Preachers’ message that God was also concerned for them and their<br />

condition.<br />

On the 9th August 1747, John Wesley visited Ireland for the first time,<br />

landing at George’s Quay, Dublin. In all, Wesley made twenty one visits<br />

to Ireland between 1747 and 1789. On one tour in August of 1762, Wesley<br />

arrived in Tyrrellspass. In his diary he noted, ‘Aug 2, Sun. I baptized<br />

Joseph English (late a Quaker), and two of his children. Abundance of<br />

people were at Tyrrellspass in the evening, many more than the house<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

15

could contain. At five in the morning one who had tasted the love of<br />

God but had afterwards relapsed into his former sins, nay and sunk<br />

into Deism, if not Atheism, was once more cut to the heart’. 1 His brother<br />

Charles Wesley, later described his own impression of what he saw, ‘the<br />

people of Tyrrellspass were wicked to a proverb, swearers, drunkards,<br />

sabbath breakers, thieves from time immemorial. But now the scene is<br />

utterly changed’. 2<br />

Tyrrellspass 1853<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was born 27th March 1853, the eldest son of <strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong> and Hannah Bagnall, a farming family who lived in the<br />

townland of Cornahir, Tyrrellspass. The other children were<br />

Eliza, Robert, Annie, Joe, Pamela-Harriet, William and Mary, also known<br />

as Molly. The <strong>Lee</strong>s were Wesleyan Methodists and were of modest means,<br />

but not poor. Little is known of <strong>Edward</strong>’s early life, but it is likely that<br />

he attended the local Protestant school in Newtownlow. He was well<br />

educated, although his later education, if any, is still to be discovered. As<br />

the eldest son, it would have been natural that <strong>Edward</strong> would work on<br />

the farm alongside his father and the rest of his family, eventually taking<br />

it over. However, this ambitious young man had other plans and began<br />

work as an indentured assistant draper, most likely in Tullamore.<br />

Eventually, in the late 1870s, with £100 he had saved and with<br />

some money, most likely from his mother Hannah Bagnall, <strong>Edward</strong> left<br />

Westmeath to make his way in the world. But he would hold Tyrrellspass<br />

dear all his life. For many years, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was remembered locally<br />

as the young man who went to Dublin and became wealthy. On 25th<br />

July 1878, he married Annie Sheckleton from Dungar Co. Offaly, in the<br />

Methodist Church in Blackrock, Co. Dublin. It is possible that the young<br />

couple had first met in Tullamore where Annie may also have worked.<br />

There is little doubt that <strong>Edward</strong>’s future success would be due to this<br />

1 The Ninth Part, Section Two (John Wesley’s Irish Tour 1762)<br />

2 Ibid.<br />

16<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

Tyrrellspass Green 1900s. Photo was probably taken by Robert Ernest or Joe <strong>Lee</strong>.<br />

Turf Cutting near Tyrrellspass, 1900s.<br />

Farming in Tyrrellspass 1900s.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

17

happy partnership. Annie, born 20th March 1859, was the second daughter<br />

of eight children of George Sheckleton and Mary Anne Carrey of Dungar<br />

Park, Roscrea. The Sheckleton family were members of the Church of<br />

Ireland. <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie moved to No.2 Goldsmith Terrace in Bray, Co.<br />

Wicklow, where <strong>Edward</strong> had been living at this time. Their first child,<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> Sheckleton <strong>Lee</strong>, was born in the house in 1879. Interestingly, the<br />

name Sheckleton became Shackleton around this time and both Annie<br />

and her first born, would use the new spelling from then on. The reason<br />

for this change is not known.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> And Co. 1885<br />

During this period, <strong>Edward</strong> was learning about the drapery<br />

trade. By 1883, he was manager of Penrose Bowles and Co,<br />

General Drapers and Outfitters, 89 Lower Georges Street,<br />

Kingstown, (Dún Laoghaire). He gained much experience in the business,<br />

all of which he would soon put to good use. It was probably at this time<br />

that he realised that good trade was to be had in coastal towns, linked<br />

by railways. In 1885, <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie decided to strike out on their<br />

own. They opened their first shop <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and Co, on the ground<br />

floor of their house at No 2. Goldsmith Terrace. This was quickly followed<br />

by another shop in Kingstown the same year. The original location of the<br />

shop was at 7, 8, 9 Anglesea Buildings, Upper Georges Street. In 1906 the<br />

shop relocated to the corner of Upper Georges Street and Northumberland<br />

Avenue, into a purpose built premises, now occupied by Dunnes Stores.<br />

This beautiful building, with its red brick and granite façade is one of the<br />

architectural ‘gems’ of Dún Laoghaire. It was designed by Kaye-Parry and<br />

Ross, who also designed the Carnegie Library in the town. Today there<br />

are still traces of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and Co. on the building. Above the corner<br />

at the junction of the two roads, there is a granite pediment with EL&Co<br />

Ltd. carved in relief. The shops operated on the ‘Cash Only’ system, ‘ONE<br />

PRICE! PLAIN FIGURES! SMALL PROFITS! CASH!’ This business model<br />

was a success.<br />

18<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and Co Ltd<br />

Dún Laoghaire (1940s).<br />

No 2 Goldsmith Terrace,<br />

Bray Co Wicklow. 1900.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> Shackleton <strong>Lee</strong> about 1890.<br />

Robert Ernest <strong>Lee</strong> about 1890.<br />

Letterhead.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

19

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie had nine children: <strong>Edward</strong> Shackleton, known as<br />

Ted, George Johnston (born 1880), Robert Ernest, known as Ernest (born<br />

1883), Hastings (born 1884), William (born 1885) Joseph Bagnall (born<br />

1888), Annie (born 1891), Alfred Tennyson, known as Tennyson (born<br />

1892) and quite a bit later, Geoffrey Patrick (born 1906). Sadly, in a time<br />

of high infant mortality, five of the infants died soon after birth, including<br />

their only daughter Annie. Tennyson was the youngest of the surviving<br />

children and was doted on by his mother. A typical Victorian middle class<br />

woman, Annie loved poetry. Her favourite poet was the Poet Laureate,<br />

Alfred Lord Tennyson. He died on the 6th October 1892. This was also<br />

the day that the new <strong>Lee</strong> child was born. In honour of the famed poet,<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie named their new son Alfred Tennyson <strong>Lee</strong>. All the<br />

children were baptised in Bray Methodist Church, on Florence Road. The<br />

church was only a few yards from the family home and the family were<br />

regular attenders there, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> even presiding at religious meetings<br />

from time to time.<br />

The boys were pupils at St. Andrew’s, a Presbyterian school in Bray.<br />

To his four sons, <strong>Edward</strong> was known as the ‘governor’. But this was only<br />

out of respect for his status as their father. Indeed, what shines through<br />

in his later letters to Tennyson is the love and affection he had for his<br />

family. This paternal attitude was extended to his dealings with his<br />

employees. In 1893, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was admitted into the Grand Lodge of<br />

Ireland Freemasons. A southern Unionist, <strong>Edward</strong> was also a fiercely<br />

proud Irishman. The business grew rapidly and in the next few years<br />

shops were opened in Rathmines and Mary Street in Dublin. A wholesale<br />

warehouse and offices operated from Abbey Street and, not forgetting<br />

his roots, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> also opened a small shop in Tyrrellspass. As the<br />

Bray store became more successful and required more space, the family<br />

moved to No.2 Wyndham Park Road in 1901. This was a solid middle<br />

class, <strong>Edward</strong>ian, red bricked, terraced house and quite a step up from<br />

living over the shop in Goldsmith Terrace. In 1904, the business became a<br />

private limited company. The Board of Directors was appointed from the<br />

managers of the various shops.<br />

20 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

Social Conscience<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was an astute and shrewd businessman, but he also<br />

possessed a strong social conscience and was always concerned<br />

for the welfare of his staff, his principle being, ‘a good day’s pay<br />

for a good day’s work’. 3 To this end, in 1889, he initiated a half day holiday<br />

for all his staff on Thursdays, later changed to Wednesdays on foot of the<br />

Shops Act, 1912. He was the first employer in Ireland to do this. He firmly<br />

believed that the working day should be shortened if possible and said,<br />

‘Where long hours are worked on Saturdays some compensation should<br />

be given by concession on another day of the week and therefore in itself,<br />

it was but an act of simple justice’. 4 He also initiated a system of profit<br />

sharing for all his employees. ‘The bonus, or rather, profit sharing system,<br />

is my highest ideal of what a business ought to be’. 5 He was concerned<br />

with the desperate plight of the less well off and to this end he entered<br />

local politics in Bray. He was elected a member of the Bray Urban District<br />

Council (UDC) in 1900 on the Unionist ticket. In the council elections of<br />

1903, he topped the poll with 303 votes. In a newspaper article in 1903,<br />

the following was noted: ‘Mr. <strong>Lee</strong> has been upon the side of the people<br />

invariably and there is no member of the community who will not give<br />

him credit for the tenacity with which he has held to his democratic<br />

convictions. He has been consistent in his efforts to abolish slumdom<br />

and to enable the workingmen of his town to enjoy decent and sanitary<br />

homes. On many political questions we were not in accord with Mr.<br />

<strong>Lee</strong>, but upon the great question of the uplifting of the masses and the<br />

amelioration of their condition we find Mr. <strong>Lee</strong> far more advanced than<br />

many with whom we agree in politics’. 6 In 1906, at the instigation of Lord<br />

Powerscourt, he was made a Justice of the Peace (J.P.).<br />

As a member of Bray UDC, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> actively promoted the erection<br />

of houses for the working people of that town, believing that, ‘it is the first<br />

duty of the council to have the poor properly housed’. 7 Housing schemes<br />

3 Wicklow Newsletter. 19/2/1927<br />

4 Unattributed newspaper clipping in <strong>Lee</strong> family archive, on the occasion of <strong>Edward</strong><br />

and Annie <strong>Lee</strong>’s silver wedding anniversary in 1903.<br />

5 ibid<br />

6 ibid<br />

7 Irish Times. 3/10/1905<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

21

Bray Urban District Councillors 1906, on<br />

completion of first phase of Purcell’s Field<br />

housing scheme. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> centre with key.<br />

The Suburban Club, Florence Road, Bray.<br />

Purcell’s Field (now Connolly Square) Bray.<br />

22 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

at Dargan Street in Little Bray and near the Town Hall were an early<br />

example from his tenure as Chairman of the Public Health and Artisans<br />

Dwelling Committee. In 1908, he was elected Chairman of Bray UDC.<br />

It was noted by Councillors that, ‘Mr. <strong>Lee</strong> was a broad-minded liberal<br />

gentleman, who had rendered yeoman service to Bray in his advocacy<br />

of schemes for the better housing of the working classes and his services<br />

deserved this recognition’. 8<br />

One of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s finest achievements was the Purcell’s Field<br />

housing scheme of 1906-1908, now Connolly Square and St. Kevin’s Square.<br />

He invited Lord Aberdeen, the Lord Lieutenant, to inspect the dwellings,<br />

proudly telling him ‘the accommodation was absolutely unique and the<br />

situation fit for a mansion’. 9 Lord Aberdeen was suitably impressed.<br />

‘A good day’s pay for a good<br />

day’s work.’<br />

On his election as Chairman of the Council in 1908, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> said,<br />

‘I had merely taken a humble part in the advancement of schemes for the<br />

better housing of the working classes, but that, I was willing to do as a<br />

humble worker in the ranks’. 10 He was proud of the attitude taken by Bray<br />

UDC members who had elected him Chairman saying, ‘that every section<br />

of creed and every form of political thought should act in so handsome a<br />

manner as the majority of the Council has done towards me’. 11 However,<br />

in September 1908, his Chairmanship of Bray Urban District Council was<br />

objected to by a gentleman called John Sloane, who said that <strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong> was no longer a resident of Bray and was now residing in Stillorgan.<br />

The objection was upheld and he was ‘accordingly struck off’ 12 the Bray<br />

Parliamentary Revisions list.<br />

On 6 th October 1908, at the Bray Technical Schools Reunion of Students<br />

and Friends, the Rev. Mr Glenn proposed a vote of thanks to <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

for presiding. Rev. Glenn was upset by the mere technicality which had<br />

8 Irish Times. 24/1/1908<br />

9 Irish Times. 30/5/1908<br />

10 Irish Independent. 5/2/1908<br />

11 Irish Times. 5/2/1908<br />

12 Irish Times. 15/9/1908<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

23

deprived Bray of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s services on the Council and Mr. Joseph<br />

W. Reigh J.P. said, ‘some gentlemen who were not able to face Mr. <strong>Lee</strong> in<br />

the open gave him a stab in the back’. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> calmly replied that, ‘It<br />

had been done by a gentleman who was perfectly entitled to do it and I<br />

had no reason to complain’. 13 However, it is most likely that <strong>Edward</strong> felt<br />

betrayed and sad upon his retirement as Chairman in December of that<br />

year. He would never again seek to be elected to any public office. It was<br />

not surprising. But it was arguably a great loss to the community that he<br />

did not get involved in local politics in Kingstown. Probably he had had<br />

enough of council politics. If he could not deliver for his fellow citizens,<br />

what was the point?<br />

‘The bonus, or rather profit sharing<br />

system is my highest ideal of what a<br />

business ought to be.’<br />

In 1911, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was appointed to the Commission of the Peace for<br />

the County of Wicklow, attending the Bray Bench. While in Bray he had<br />

donated £100 towards the equipping of the library in 1910 and had paid for<br />

renovations to the Methodist Church. He also donated a house on Florence<br />

Road for the formation of a club for people in trade. The Suburban Club as<br />

it is known, is still in existence in the same house today. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was<br />

elected the first president. He was a man who held strong opinions on<br />

many subjects, especially on business, local and social issues. He was not<br />

afraid to take a stand on anything he felt was unfair. For example, some<br />

years earlier, the threatened closure of Kynochs Explosives Factory in<br />

Arklow in 1907 had been seen as an attempt by English rivals to transfer<br />

the business to England. At the Bray UDC meeting of June 4 th 1907 there<br />

was much heated discussion on this topic. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> as a man of fair<br />

play and an Irishman was indignant on the matter, ‘It would be nothing<br />

short of a public disgrace if this attempt to ruin Arklow were persisted in.<br />

This was an occasion on which Irishmen of all classes should join and say<br />

to English intriguers, hands off this industry’. 14<br />

13 Freeman’s Journal. 7/10/1908<br />

14 Irish Times. 5/6/1907<br />

24 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

The Grange<br />

By the early 1900s, the <strong>Lee</strong> family had moved from Bray into<br />

an imposing mansion on the Stillorgan Road in Co. Dublin.<br />

The Grange was a large and beautiful house with extensive<br />

grounds, all enclosed behind a high wall. Parts of the wall and some<br />

traces of the estate cottages still exist today. They can be seen from the<br />

main Stillorgan Road at the junction for Brewery Road. The family would<br />

live here until 1914. The years at The Grange would turn out to be the<br />

happiest the family would spend together. It must have been a magical<br />

place for the young boys. Photographs of the time show a family with<br />

all the attendant privileges of a prosperous middle class. The extensive<br />

grounds contained a small boating lake, dairy, croquet lawn and a tennis<br />

court. A typical <strong>Edward</strong>ian scene, with tennis matches and afternoon tea<br />

in the garden listening to Sir <strong>Edward</strong> Elgar and Count John McCormack<br />

on the new cylinder gramophone. Although they employed a gardener,<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie <strong>Lee</strong> were themselves keen gardeners and won prizes<br />

at local garden shows for their produce. The staff included a butlerchauffeur,<br />

two housemaids, a cook and, for a short time, a nanny for<br />

Patrick, the youngest son, who would sadly die within months of his birth<br />

in 1906. There was also a companion for Annie <strong>Lee</strong>. Annie Cosgrave, a<br />

Roman Catholic and a Wexford woman, had originally worked for the<br />

Darley Family. The Darleys had lived in The Grange until 1901 and it<br />

would seem that Annie Cosgrave had stayed on to work for the <strong>Lee</strong>s.<br />

Annie Cosgrave would spend the rest of her life as a respected member of<br />

the <strong>Lee</strong> household.<br />

The two eldest boys, <strong>Edward</strong> ‘Ted’ <strong>Lee</strong> and Robert ‘Ernest’ <strong>Lee</strong>,<br />

attended Wesley College in Dublin and the younger two, Joseph Bagnall<br />

<strong>Lee</strong> and Alfred ‘Tennyson’ <strong>Lee</strong>, were boarders at Epworth Methodist<br />

College in Rhyl, North Wales. <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie loved to entertain at<br />

The Grange. There was a grand ballroom where dancing and parties took<br />

place. Sometimes the <strong>Lee</strong> boys would help and act as waiters. In 1903,<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie’s silver wedding anniversary was celebrated there<br />

with a wonderful party for family, friends and <strong>Lee</strong>’s employees. The<br />

highlight was the presentation of a beautiful framed illuminated address<br />

from all the staff of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> & Co.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

25

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> (standing extreme right) and extended family. Powerscourt. <strong>Edward</strong>ian picnic. 1906 approx.<br />

Robert Ernest and Annie <strong>Lee</strong><br />

left of picture, with relatives<br />

at the Grange.<br />

Nanny with Baby Geoffrey<br />

Patrick and Annie <strong>Lee</strong>, 1906.<br />

Royal City of Dublin Hospital, (Baggot St)<br />

Resident Staff 1909-10. Robert Ernest <strong>Lee</strong><br />

(sitting second from right).<br />

The Grange,<br />

Stillorgan Road<br />

1900s.<br />

Extended family gathering<br />

at the Grange. Circa 1906-8.<br />

Law Students.King’s Inns 1909-10.<br />

Joe <strong>Lee</strong> (sitting centre.).<br />

Left to right, <strong>Edward</strong> ‘Ted’, Annie <strong>Lee</strong>, Tennyson,<br />

Unknown, Unknown, Joseph, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

enjoy afternoon tea listening to Gramophone<br />

in The Grange garden circa 1906.<br />

26<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

Silver Wedding Illuminated scroll 1903.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

27

The four brothers attended Trinity College. Robert Ernest graduated<br />

as a medical doctor and Joe also attended the King’s Inns studying to be<br />

a barrister. Ted trained as an accountant and would become the firm’s<br />

secretary. Tennyson, the youngest, gained an M.A. and would also<br />

eventually enter the family business. The family now attended St Brigid’s<br />

Church of Ireland in Stillorgan. Although all the family, except Annie,<br />

were Methodists, there was a gradual transfer to the Church of Ireland.<br />

In 1907, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was involved in the Irish International Exhibition<br />

as a member of the Executive Council of Exhibits and Space Committee.<br />

The successful businessman William Martin Murphy was also involved<br />

as a vice-president. <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie were presented to their Majesties<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> VII and Queen Alexandra when they visited the exhibition.<br />

Never forgetting his roots, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> brought 300 family, friends and<br />

neighbours, at his own expense, from Tyrrellspass up to Dublin to visit<br />

the exhibition as his guests. They were all treated to lunch and a tour<br />

of the exhibition before returning home by train. Interestingly, a few<br />

years earlier, in March 1904, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> as a member of the Dublin<br />

Mercantile Association had proposed a motion to consider the holding<br />

of an International Exhibition in Dublin in 1906. 15 It is most likely that he<br />

had decided to travel to America in 1904, with this idea in mind, to see for<br />

himself how this could be achieved.<br />

America And Canada 1904<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was a proud and patriotic Irishman. He loved<br />

his country and would promote Ireland and its people at<br />

every opportunity. He was a firm believer in his fellow<br />

Irishmen and women. ‘Ireland is a country endowed with so much<br />

natural beauty, fertile resources and above all with such a talented<br />

and splendid people’. 16 His love for his country and his concern for<br />

his fellow countrymen, especially in what he saw as the scourge of<br />

emigration, is well described in his Memoranda of a Hurried Visit to<br />

15 Irish Times. 11/4/1904<br />

16 Irish Times. 24/12/1904<br />

28 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

America and Canada 17 which he published privately on his return from<br />

the month long visit in May and June 1904, accompanied by his good<br />

friend Robert Reid Thomson. It was dedicated to his friend, ‘With very<br />

sincere regard to my fellow-traveller and friend, tried and true, R. Reid<br />

Thomson, Esq’. This publication is reproduced in full in the Appendix.<br />

Travelling from Queenstown in Cork on the train, he described the<br />

landscape and his sadness for the people he saw through the carriage<br />

window. He was also wistful about his own boyhood memories, ‘The<br />

pasture lands of Kildare and the bogs of King’s County are replaced by<br />

the Queen’s County hills to the left. Memories of my boyhood days crowd<br />

in upon me, as a holiday of some few days I spent there in years gone by<br />

still marks time on my memory. Perhaps no land can produce greater<br />

diversity of creed and character than Ireland. Pathetic was the scene at<br />

Portarlington, where the observant Irishman and others may have seen<br />

the life-blood of the nation slowly bleeding the country white in the tide<br />

of emigration, which has not been stemmed for even one decade, since its<br />

first flow nearly fifty years ago’.<br />

‘Ireland is a country endowed with so<br />

much natural beauty, fertile resources<br />

and above all, with such a talented<br />

and splendid people.’<br />

Although the two men were travelling in luxury to New York on the<br />

White Star Liner RMS Oceanic, he was not immune to the plight of the<br />

steerage passengers, noting sadly, ‘Alas, for human hopes! One of our<br />

fellow-travellers in the steerage died this evening quite suddenly. The<br />

touch of Nature which makes the whole world kin was immediately<br />

felt, as evidenced by the expression of sympathy heard on all sides. The<br />

poor fellow who was travelling all alone will be committed to the deep at<br />

8.30 tomorrow evening over 1000 miles from his no doubt dearly loved<br />

country, for he was an Irishman’. However his sense of equality was<br />

shaken the next day when he was informed that at the funeral service,<br />

‘State-room passengers were not allowed to be present’.<br />

17 Memoranda of a Hurried Visit to America and Canada by <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

29

As the Oceanic glided up the Hudson River towards the port of New<br />

York, <strong>Edward</strong>’s wonderment at the new sights he was witnessing was<br />

evident, ‘Its sky-scrapers, you have to see them to believe, from 20 to 32<br />

stories in height is quite usual’. However he was not as taken by Central<br />

Park. Again the Irishman, proud of his country, writes. ‘What a poor<br />

show compared with our magnificent Phoenix Park’. Travelling on to<br />

Philadelphia, the two friends were impressed with Independence Hall<br />

and the home of William Penn, the founder of the state. The two men<br />

visited the Baldwin Loco Works and were amazed by the industry there,<br />

turning out 2,000 locomotives a year. They continued on to Washington,<br />

where they discovered that commercial rates for the city were very high.<br />

This fact, no doubt, struck a chord with the businessman and councillor<br />

in him. His only comment being, ‘a cry we are not unused to at home’.<br />

In Washington, <strong>Edward</strong> and Robert attended a Sunday religious<br />

service at the Eleventh Street Block ‘K’ Church where they ‘heard a<br />

good address and some good singing, my friend and myself being the<br />

only white persons present’. Later however, the two men, on entering a<br />

railway car, were puzzled by a card at one end on which was written the<br />

single word ‘WHITE’. They soon realised that it was a notice to keep the<br />

‘whites’ and ‘coloureds’ separated. His only comment on this apartheid<br />

was, ‘and so it is ordained here’ - an oddly resigned remark perhaps,<br />

considering his fight for social justice and equality at home. It implies a<br />

certain, if uncomfortable, acceptance of this overt injustice. He was not<br />

in Ireland now, he was just a tourist and he had no influence in the New<br />

World. The next stop was Louisville, Kentucky, and although he admired<br />

the wonderful scenery he observed on the train journey, his natural bias<br />

towards his beloved Ireland again seeped through in his observations.<br />

‘But however beautiful, the fine homesteads of the old country have no<br />

counterpart in this’. Arriving in city of Louisville on Tuesday evening,<br />

May 31 st , the two friends made their way to the Seelbach Hotel. At the<br />

reception desk, the two men were approached by a newspaper reporter<br />

from the Louisville Courier Journal, seeking an interview with them.<br />

Seeing as they were from Ireland, the reporter implored the two men, ‘to<br />

tell him a story, but to no effect. We were not to be drawn’.<br />

The two travellers were amused by the persistence of the journalist.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> noted, ‘the newspaper reporters of this country are very versatile<br />

gentlemen. This gentleman, who only overheard a remark made by my<br />

friend at the office on going to register, construed it into a good length<br />

30 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

paragraph in the next day’s issue of the paper he represented’. The article<br />

appeared the next morning in the On Dit column of the Louisville Courier.<br />

It contained all the stereotypical stage Irishness that one would expect<br />

from an American’s idea of the Irish at that time,<br />

‘Faith and he has the face of Tim Harrington, our own Lord Mayor,’<br />

cried R. Reid Thomson and <strong>Edward</strong> Ahl [<strong>Lee</strong>] in concert, as they walked to<br />

the desk at Seelbach’s Hotel last night and gazed upon the countenance of<br />

H.M. Secor, the night clerk, who became confused under the affectionate<br />

glances and winced visibly before the two Irishmen. ‘You must excuse<br />

us if we gaze too steadily,’ continued Mr. Ahl, [<strong>Lee</strong>] the spokesman, ‘but<br />

it carries us all the way back to Dublin to look on your face. We are<br />

travelling 10,000 miles.’ The two Europeans are typical of their race and<br />

the Irish brogue was broad in their speech. They have amassed a fortune<br />

by constant application to business and in the prime of life they decided to<br />

visit America. Both are greatly pleased with America and from Louisville<br />

they will go to the Exposition at St. Louis’. 18<br />

They might have been greatly pleased with America, but it would be<br />

interesting to know how they felt at being lampooned. I would imagine<br />

the two gentlemen had a good laugh about it. The two companions<br />

were now off to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. What <strong>Edward</strong> would<br />

see there would, no doubt, inform his thoughts and ideas for the Irish<br />

International Exhibition in Dublin a few years later. However, <strong>Edward</strong><br />

was none too impressed with what he saw, ‘It was apparent that too<br />

much was attempted by even so great a nation as America, that more<br />

concentration of effort on half of the space would have brought better<br />

results’. He was particularly upset with the Irish exhibits.<br />

‘We made our way to what was intended to be a representation of<br />

the Bank of Ireland, but oh, what a farce to place before the Americans<br />

as a representation of the noble pile of buildings in College Green,<br />

our old historic Houses of Parliament. Why is Ireland to be always<br />

handicapped? Here we have her exhibits almost at the entrance of the<br />

Exhibition, detached from all others and a quarter dollar extra to be<br />

charged for seeing them. One is really puzzled from a businessman’s<br />

point of view, whether it is an effort to help Irish Industries, having as<br />

auxiliaries a restaurant concert hall, side shows, etc., or is it the other<br />

18 Courier Journal, Louisville. June 1 st 1904 (Note: <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> writes that he is<br />

probably responsible for the mistaken Ahl (<strong>Lee</strong>) surname ‘not having written my<br />

name as carefully as I might in the Hotel register’.)<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

31

way about, helping the side shows, restaurant, concert hall, having Irish<br />

manufacturers as auxiliary and subsidiary. One felt indignant to see our<br />

finest street in Dublin, Sackville Street, outraged in such a fashion, a street<br />

of scarcely ordinary width, narrow side paths, paved with cobble stones,<br />

no sign of tram lines or indeed of life at all, a hideous nightmare of what<br />

the street could never come to’. It was not all bad though and both men<br />

were impressed by what they saw next. ‘We passed through the Buildings<br />

of Agriculture and Horticulture. The former was the most magnificent<br />

show I have ever seen’.<br />

Later, the two men called on a gentleman from Ireland who was about<br />

their own age. The man said that he, ‘regretted the day he came to this<br />

country, although occupying what seemed to us a very good position and<br />

for which he said he got big money, still the conditions of life were so far<br />

behind the old country as to make him regret leaving it’.<br />

The month long journey continued to Chicago. <strong>Edward</strong> realised the<br />

city’s importance to business, but was uneasy about the great wealth<br />

that could be amassed by an individual. He said ‘as a city of commercial<br />

importance I quite see it stands in the front rank, if not first in the front<br />

rank, in America and would doubtless give an enterprising young man<br />

five opportunities for one he would have in the old country of winning<br />

wealth, if that was his only goal’. This is an interesting comment by<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and goes some way towards explaining his philosophy of<br />

life. As a man of strong moral beliefs, having wealth acquisition as one’s<br />

primary aim would not sit well with him. Chicago as a place to live did<br />

not appeal to either gentleman.<br />

Tuesday 7 th June found <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and R. Reid Thomson at Niagara<br />

Falls. This time the two friends were genuinely impressed. ’About five<br />

minutes’ walk from the hotel brought us to the bank to see the Rapids above<br />

the Falls and oh! What a sight. The great St. Lawrence River, unequalled<br />

I should say in the world, staid, stately and placid, a few hundred yards<br />

above, is now preparing for its tremendous leap to the bed below. On it<br />

comes, gathering strength and velocity, the very embodiment of supreme<br />

power and grandeur, while the final leap baffles the descriptive power of<br />

any pen. Although we have had opportunities of seeing some of America’s<br />

great rivers, the Hudson, Delaware, Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio, this<br />

one, for beauty, grandeur and strength, far out classes them all’.<br />

It is likely that <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> had been influential in the decision of<br />

32 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

his nephew Robert H. Gilbert 19 to emigrate, along with his mother Mary<br />

and sister Violet, to America in May 1908. Robert would end up living<br />

in Buffalo, New York, working on the streetcars. In time he would go<br />

on to organise the Niagara Frontier Bus and Streetcar Employees’ Union,<br />

eventually becoming its president. Did his uncle <strong>Edward</strong> give him advice<br />

about the opportunities he saw for a young man in the New World? We<br />

will never know, but it is most likely that he did, given <strong>Edward</strong>’s love of<br />

family and the idea of bettering one’s self. It is also quite a coincidence<br />

that young Robert should start his new life in Buffalo, close to Niagara<br />

Falls.<br />

After breakfast on Wednesday June 8 th , <strong>Edward</strong> and Robert Reid<br />

Thomson headed for Toronto. Not having been entirely at ease with<br />

American brashness, <strong>Edward</strong> wrote, ‘the Americans certainly have a way<br />

of putting themselves en evidence that no ‘old worlder’ can match’. The<br />

two men were much more comfortable in Canada. ‘We are soon under the<br />

British flag again. The country seems different, their manners different<br />

and to our way of thinking, more in accord with old world sentiment’.<br />

Diplomacy was obviously another of <strong>Edward</strong>’s traits. His impression of<br />

Toronto was positive. ‘The ‘strenuousness’ of life in other cities we have<br />

seen, is nowhere apparent, in fact home life here is well exemplified’.<br />

A highlight of their time in Toronto was a visit to the T. Eaton Co.,<br />

founded in 1869 by Timothy Eaton, an immigrant from Clogher, Co<br />

Antrim. The T. Eaton Co. became one of Canada’s most successful retail<br />

stores, with branches across the country. Of major interest to <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

was the fact that Eaton had pioneered the ‘cash only’ system of retailing.<br />

This, of course, was also the way <strong>Lee</strong>'s transacted business, albeit on a<br />

much smaller scale. But there were other parallels with the two men. Both<br />

were quiet, private individuals with strong moral characters, a strong<br />

work ethic and a wish to succeed. Both men were religious and pursued<br />

a fair-minded and generous approach to their employees. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

was genuinely excited by what he saw. ‘We marvelled at the enormous<br />

streams of people passing in and out - not all necessarily customers’.<br />

It would be interesting to know if <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> had been influenced by<br />

Timothy Eaton’s pioneering retail innovations years earlier while setting<br />

up his own business.<br />

19 Robert H. Gilbert, born in Bandon, son of William John Gilbert and <strong>Edward</strong>’s sister,<br />

Mary (Molly).<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

33

After visits to Montreal and Quebec, it was back to Boston for the two<br />

men and then on to New York, where the two friends dined at Delmonico’s<br />

before heading for the return journey home. The sea voyage on the White<br />

Star Liner RMS Cedric was for the most part uneventful and the diary<br />

entry for Thursday June 16 th 1904 simply states, ‘a very enjoyable day<br />

and passed without incident of any note, ship taking a straight course<br />

eastward, about 1,000 miles south of Ireland. Weather still warm and<br />

fine’. Back in Dublin on that very day, an incident of a very definite note<br />

was occurring which would forever after have a profound influence on<br />

world literature. A young man had just plucked up the courage to ask a<br />

certain young woman out for the first time. The man in question was, of<br />

course, James Joyce and his sweetheart was Nora Barnacle. 16th June is<br />

now celebrated as Bloomsday.<br />

On the morning of Wednesday June 22 nd , the Cedric docked in<br />

Queenstown (Cobh), Co Cork. <strong>Edward</strong> was glad to be back in Ireland.<br />

‘What a feeling of thankfulness took possession of me as I took refuge in<br />

a bed in the Old Country and while I think the journey worth the money<br />

many times over, I can well understand that one is not fully repaid till he<br />

experiences the luxury of coming home again’. He was acutely aware,<br />

that this luxury was not available to most Irish people and sadly observed<br />

the poor and the wretched as they carried their few possessions and<br />

children towards, what they hoped, would be a better life. ‘The Teutonic is<br />

just visible inside the harbour, waiting to convey to the New World many<br />

who will never see the Old Land again’.<br />

The next day, whilst waiting for the train in Cork, he decided to take a<br />

walk down Patrick Street, noting the people along the way. ‘I was glad to<br />

see the kindly faces of my own countrymen again and to be where the same<br />

‘knock aside everyone in your way’ principles do not obtain’. Although he<br />

could be accused of being overly sentimental in his observations, it must<br />

be remembered that his publication was originally written only for his<br />

close friends and family. For all his business acumen and his concern for<br />

people’s well-being and his genuine love of Ireland, most precious to him<br />

was his family. He fondly wrote, ‘I now close the memoranda of my visit<br />

as I leave Portarlington Station at 4.45pm, hoping to reach before sunset,<br />

the fairest and best spot on earth to me – Home’.<br />

34 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

Cluster of skyscrapers, New York. Circa 1900.<br />

Publisher, Detroit Publishing Co. Source, Library of Congress<br />

via Detroit Publishing Company Photograph Collection.<br />

King Street looking West, Toronto.<br />

1900s. John Chuckman Collection<br />

- Vintage Toronto Postcards<br />

Agriculture Building, World Fair,<br />

St. Louis. c. St. Paul: R. E. Steele,<br />

1904. Source, Library of Congress.<br />

Print showing bird’s-eye view of<br />

fairgrounds at the St. Louis fair.<br />

Drawn by C.N. Dry. Source,<br />

Library of Congress.<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

35

Benefactor<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> and Annie <strong>Lee</strong> were benefactors to many good causes<br />

and charities and both were life governors of The Royal<br />

Hospital for Incurables in Donnybrook where their son Robert<br />

Ernest was Resident Medical Officer, 1912-13. The business had subscribed<br />

three guineas a year to the hospital from 1900, eventually increasing the<br />

subscription to five guineas. This annual donation would continue long<br />

after <strong>Edward</strong> and Annie’s deaths. Donations were also made to Baggot<br />

Street and Jervis Street Hospitals and many other institutions and causes.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was a member of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and the<br />

Dublin Mercantile Association. He had extensive business interests and<br />

was a Director of Dublin Distillers and the Mining Company of Ireland. In<br />

1910 he built houses at the back of <strong>Lee</strong>’s shop in Dún Laoghaire. Named<br />

after the birthplace of ‘one of the best women in the world - his wife’,<br />

Dungar Terrace was a lovely little street with beautifully designed terraced<br />

houses, all rented out for a modest sum. The cost of this development<br />

was £7,000, a very large sum at the time. But this all accorded with<br />

<strong>Edward</strong>’s social principles. ‘They had tenants in Dungar Terrace from<br />

Dublin, Rathmines and Rathgar. He thought the houses were wanted in<br />

Kingstown. They expended a great deal of money in building, but they<br />

only asked for a small return on their capital’. 20<br />

In an article entitled ‘Leading Kingstown Traders’, published in The<br />

Freeman’s Journal on the 17 th May 1913, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was again held up<br />

as a caring and progressive employer. ‘One establishment in particular<br />

stands out boldly, a commercial watchtower in itself, jealously guarding,<br />

as it were, its companions in trade; its house-flag flying and proclaiming<br />

to all and sundry that these are the premises of <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> and Co. Ltd.<br />

What an asset such progressive firms are to a township like Kingstown<br />

may be judged from the fact that within a few years Messrs. <strong>Lee</strong> have<br />

erected in brick and mortar alone property of the estimated value of<br />

£26,000, truly a marvellous march of commercial progress for one firm<br />

alone. This may be in one sense, however, understood when we consider<br />

the unfailing devotion to work and loyalty of the staff to an employer, who<br />

20 Irish Independent. 14/6/1910<br />

36<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

certainly, as such, has no rival in the three kingdoms and who, we believe,<br />

so ungrudgingly devotes his best interests at all times to their welfare. Not<br />

by any means the least claim to notoriety by Messrs. E. <strong>Lee</strong> and Co. Ltd,<br />

is the fact that the firm 25 years ago, voluntarily gave their assistants the<br />

half holiday, the subsequent cause of so much argumentative legislation<br />

years afterwards’. 21<br />

DUNGAR TERRACE 1910.<br />

1913 Lockout<br />

The Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) was<br />

founded in Dublin by James Larkin in 1909. It was set up on<br />

socialist principles, to help change society in favour of the<br />

working class and to give unskilled workers political and industrial clout<br />

and bargaining power with the employers. However, the employers saw<br />

Larkin and his union as a threat. Under the leadership of William Martin<br />

Murphy, owner of the Irish Independent and the Dublin Tramways<br />

Company, matters came to a head on 15th August 1913, when Murphy<br />

told his staff in the despatch department of the Irish Independent, that if<br />

they joined the union they would be fired. As the workers were dismissed,<br />

the dispute escalated. The tram drivers stopped work and were also<br />

21 Freeman’s Journal. 17/5/1913 p11<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

37

Locked Out Workers outside ITGWU (Irish Life 1913).<br />

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>.<br />

Jim Larkin.<br />

Tom Kettle.<br />

William Martin Murphy.<br />

James Connolly.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> Letter Irish Independent<br />

23 September 1913.<br />

38 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

dismissed. The employers held out, locking out the employees until such<br />

time as they agreed to sign a pledge not to join the ITGWU. On Sunday<br />

31 August, crowds turned out on Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street)<br />

to hear Jim Larkin speak. As the police moved in to arrest Larkin, there<br />

was a baton charge. There were many injuries and public opinion was<br />

shocked at the scenes in Dublin. James Connolly, socialist and founder<br />

of the Irish Citizen Army, also became involved, closing the port of<br />

Dublin. Meanwhile, the families of the locked out men suffered extreme<br />

deprivation.<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was deeply concerned with the deteriorating situation<br />

and with the terrible consequences for the families of the locked out men.<br />

He was also concerned about the effects of the strike on commerce in<br />

general and, as a pragmatic businessman, on his own business too. There<br />

is no record of his personal thoughts about Jim Larkin or James Connolly.<br />

But he disagreed with the tactics of William Martin Murphy. <strong>Edward</strong><br />

<strong>Lee</strong> was not the only moderate employer in disagreement with Murphy.<br />

Alexander Hull, a builder and James Shanks, who had been involved<br />

in the Lord Mayor’s conciliation attempt, were also unhappy with the<br />

employers’ strategy. However, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was the only one apart from<br />

James Shanks, who publically broke ranks with Murphy and the other<br />

employers. 22 In a letter to the newspapers, 23rd Sept 1913, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong><br />

addressed both employers and workers, trying to find a compromise<br />

between them. It was, to his way of thinking, ‘an ideal realisable’. A plea<br />

to both sides, his letter continued, ‘The workers must give up the baneful<br />

doctrine of ‘tainted goods’ and the consequent ‘sympathetic strike’. ‘The<br />

employers should withdraw the pledge requiring their employees to<br />

cease to belong to the Transport Workers’ Union. To my way of thinking<br />

such a pledge is an unfair interference with the personal liberty of the<br />

worker, though I am sure the employers did not intend it as such’.<br />

This letter once again clearly shows his respect for working people,<br />

whilst diplomatically chiding the other employers. ‘Employers ought<br />

rather to seek to elevate those whom they employ than to inflict an<br />

indignity on them’. 23 But <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was also careful to appear to be on<br />

side with his co-employers at this point and he avoided lecturing them by<br />

a skilful use of language: words like ‘should’ and ‘ought’ being used as a<br />

moral imperative to persuade the employers towards a change of heart.<br />

22 Yeates. Lockout Dublin 1913<br />

23 Irish Independent/ Freeman’s Journal. 23/9/1913<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage 39

In contrast, unusually for him, his tone to the workers is more in keeping<br />

here with the employer class, saying the workers ‘must’. He was treading<br />

a fine line, trying to find a middle ground, reaching out to the workers<br />

while not alienating himself from the chamber.<br />

James Connolly was interviewed by the Freeman’s Journal the next day<br />

about <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s suggestion for a conference to break the deadlock.<br />

He did not agree. ‘My complaint about Mr <strong>Lee</strong>’s letter is that he appears<br />

to wish both sides to give way at the outset on the very points that are<br />

alleged by both sides to be in dispute. We are quite willing to let things<br />

remain as they are both sides in a state of armed neutrality as it were,<br />

towards each other and to discuss these points and any other points that<br />

may be brought up’. 24 Ironically perhaps, the employers also disagreed.<br />

J. Doyle writing to The Irish Independent on 30 th Sept stated, ‘Can Mr<br />

<strong>Lee</strong> or any other person tell us how, without such an assurance, any<br />

employer can be reasonably expected to continue to invest his capital in<br />

a business the fate of which is practically at the mercy of the insolent and<br />

unscrupulous strike boss who has recently enunciated the doctrine: ‘Do<br />

away with the employer and there is no need for a strike’. 25 But Professor<br />

Tom Kettle, one time Member of Parliament for East Tyrone and Home<br />

Rule supporter, was in agreement with <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>. In the Freeman’s<br />

Journal, 24 th September 1913, he wrote, 'It seems to me the time has come<br />

to call a truce. That is the desire of every Dublin man who loves Dublin.<br />

The letter yesterday of that model employer Mr <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>, the common<br />

tenor of conversation lead us hopefully to that haven. A middle course<br />

must and shall be found. Mr. <strong>Lee</strong> has spoken for the business world of<br />

Dublin, facts accumulate upon the facts in the direction of peace’. 26 (Kettle<br />

died not long afterwards at the Battle of the Somme, September 1916.)<br />

‘Employers ought rather to seek to<br />

elevate those whom they employ than<br />

to inflict an indignity on them.’<br />

A man of strong principles, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> joined the Dublin Industrial<br />

Peace Committee. He was the only employer to do so. The committee,<br />

24 Freeman’s Journal. 24/9/1913<br />

25 Irish Independent. 30/9/1913<br />

26 Tom Kettle, Freeman’s Journal. 24/9/1913<br />

40 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>

under the chairmanship of Tom Kettle, included writer Pádraig Colum<br />

and future 1916 Rebellion leaders, Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph<br />

Plunkett. In 1966, Plunkett’s sister Geraldine, was interviewed by RTÉ<br />

television about her brother and his political and revolutionary activities<br />

during The Rising. She also spoke about Joseph’s 1913 involvement with<br />

the Peace Committee. ‘He took no part in anything until the 1913 strike.<br />

There was a Peace Committee got up by Tom Kettle and he got all sorts<br />

of other people into it. Frank Skeffington and Willie Yeats was in it and<br />

the Dean of St. Patrick’s and one employer, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>. They were<br />

exactly the kind of people as you would find in such a thing today. They<br />

tried to make peace between the two sides and of course the employers<br />

immediately labelled the Peace Committee as pro labour and refused to<br />

have anything to do with it’. 27<br />

At a meeting of the Peace Committee in the Mansion House on Tuesday<br />

7 th October, 1913, a resolution was put by Professor. E.P. Culverwell. It<br />

stated that it was time for a truce to be declared between the employers<br />

and workers so as to save the trade of the city of Dublin from ruin and<br />

its inhabitants from starvation. 28 <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> supported the resolution<br />

saying, ‘Fortunately or unfortunately he represented the employing class<br />

and, of course, they would give him credit for saying that he was not<br />

going to say anything prejudicial to that class that night. He was glad to<br />

notice that there were some other employers also and a good many of<br />

the employed. We came here as brothers in the City of Dublin. We are<br />

not going to go into the merits of the case. What the resolution means,<br />

I suppose, is that terms will be suggested from this meeting that may be<br />

brought to both employers and employed to try to bring them together<br />

to settle the dispute in a manner that may leave no feelings of animosity<br />

behind. I am prepared to work night and day to give all assistance I<br />

possibly can, so that this unfortunate dispute may be brought to an end’. 29<br />

‘Men of Capital ought to be ashamed to<br />

have it go out to the ends of the earth<br />

that so many families were living each<br />

in one room.’<br />

27 On behalf of the Provisional Government – Joseph Plunkett RTÉ 1966<br />

28 Irish Times. 11/10/1913<br />

29 Irish Times. 8/10/1913<br />

Model Employer and Man of Moral Courage<br />

41

Another meeting of the Dublin Industrial Peace Committee was held<br />

in the Mansion House at the end of October. <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> felt that there<br />

were wrongs on both sides, but his anger was reserved for his fellow<br />

employers. ‘Men of capital ought to be ashamed to have it go out to the<br />

ends of the earth that so many families were living each in one room’. 30<br />

With this emotional statement, <strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>, hoped to force the capitalist<br />

and employer class to look closely at themselves, to examine their<br />

consciences and the morality of what they were inflicting on workers and<br />

their families. As President Michael D. Higgins recently stated, ‘There is<br />

no limit to what courageous people can do if they have ‘moral courage’. 31<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong> was courageous and he had ‘moral courage’. Unfortunately<br />

many of the ‘men of capital’ didn’t and they seemed to be impervious to<br />

<strong>Edward</strong> <strong>Lee</strong>’s plea and to the misery they were inflicting. The war would<br />

continue, morality was just another casualty. Ultimately, however, the<br />

Dublin Industrial Peace Committee failed in its endeavour to bring peace.<br />

When the Dublin Chamber of Commerce met on the 29 th November,<br />